-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2014; 4(6): 156-159

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20140406.04

Assessment of Multiculturalism of Primary Schools’ Music Teachers in Malaysia

Kwan Yie Wong1, Kok Chang Pan1, Shahanum Mohd Shah2

1Music Department, Cultural Centre, University of Malaya, Malaysia

2Faculty of Music, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Kwan Yie Wong, Music Department, Cultural Centre, University of Malaya, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study examined the level of multiculturalism in terms of life experience, personal attitudes, personal behaviour and professional behaviour amongst the Malaysian primary schools’ music teachers. A sample of 456 primary schools’ music teachers from Malaysia participated in this study. This study utilized an adaptation of the original Personal Multicultural Assessment, to measure the level of primary schools’ music teachers’ multiculturalism. Results indicated that the primary schools’ teachers in Malaysia are functioning at varying levels of multiculturalism across various situations.

Keywords: Multiculturalism, Primary schools, Music teachers, Attitudes, Behaviour, Malaysia

Cite this paper: Kwan Yie Wong, Kok Chang Pan, Shahanum Mohd Shah, Assessment of Multiculturalism of Primary Schools’ Music Teachers in Malaysia, Education, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 156-159. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20140406.04.

1. Introduction

- Diversity and plurality has existed in human society as early as human civilization began. (Rozita Ibrahim, 2007). According to Hall (2000), each country has its own specific multiethnic and multicultural practices. Despite this, such multicultural countries like the USA, Britain, Sri Lanka, Indonesia and European countries still share the same features of having culturally heterogeneous societies. Today, among Southeast Asian countries, Malaysia is considered as one of the most plural and multiracial countries (Zaleha Kamaruddin & Umar A. Oseni, 2013). Multiculturalism covers two important aspects: 1) The theory of diversity in every sense of the word, which includes diversity of ethnic origin, gender, religious practice, language used and sexual preferences; and 2) The management of these diverse aspects of social life by the different nations around the world (Goldberg, 1996; Gunew, 2004). The formation of a multicultural nation at the present day has two distinct patterns of multiculturalism which are liberal multiculturalism and postcolonial multiculturalism (Yilmaz, 2010). Liberal multiculturalism is the result of the impact of immigration on an established national culture and society, like what we see in most Western nation-states policies. On the other hand, postcolonial multiculturalism is the transformative impact of large-scale immigration which had taken place long before the country became independent (such as Malaysia and Singapore). Hence, the challenge faced by these nations will also be different due to the difference in the history of multiculturalism in each country (Raihanah Mohd Mydin, 2009).The Malaysian multiracial society is often described by ethnicity and religious multiplicity (Zaid Ahmad, 2007). Malaysia is inhabited by over 28 million people typified by the three ethnic groups of Malays (the largest ethnic group making up 67.4% of the population which include the Bumiputera (Orang Asli, Kadazan, Bajau, Iban, Melanau, Bidayuh, Penan, etc.), Chinese (the second-largest ethnic group making up 24.6% of the population) and Indians (making up 7.3% of the population); and other minority races (making up 0.7% of the population, such as Arabs, Sinhalese, Eurasians, etc.) who live together in peace and harmony (Department of Statistics, 2010). This multiplicity reveals the population structure of Malaysia in terms of ethnic, race, culture and religion. Nevertheless, the Malaysian government continues to utilize approaches that promote national unity and inter-ethnic integration in order to sustain inter-racial harmony (Najeemah Mohd Yusof, 2005).Together with balanced acknowledgment and compliments towards differences among Malaysians, the people have shown their appreciation and respect towards cultural diversity in many ways. Consequently, this action has minimized the effect of segregation in the multicultural society. Despite the differences between each ethnic group, the nation also plays a vital role to ensure everyone lives together peacefully. A political system has been plotted by the nation of the country to accept the ethnic diversity and social challenges.Purpose of the studyThis study examined the level of multiculturalism in terms of life experience, personal attitudes, personal behaviour, and professional behaviour amongst the primary schools’ general music teachers in Malaysia. In order to achieve this purpose, the following research question was addressed:1. What are the current levels of multiculturalism in terms of life experience, personal attitudes, personal behaviour, and professional behaviour amongst primary schools’ general music teachers in Malaysia as measured by the Personal Multicultural Assessment? For the purpose of clarity, the following operational definition of terms was employed: (a) life experience: social situations that the primary schools’ music teachers enter, evaluates, participates in and is finally changed by; (b) personal attitude: respond in a consistently favourable or unfavourable manner with respect to multiculturalism; (c) personal behaviour: primary schools’ music teachers’ response to situations and action toward multiculturalism; (d) professional behaviour: a response to situations or an action toward multiculturalism by the primary schools’ music teachers within the professional realm of life.

2. Method

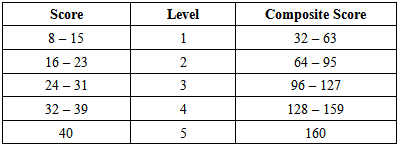

- Participants and proceduresSubjects for this study were 456 primary schools’ music teachers in Malaysia. The sample was classified according to age, gender, ethnic group, religion, and years of teaching experience. Subjects included male and female general music teachers representing the different ethnic groups of Malaysia, i.e., Malay (n=266), Chinese (n=140), Indian (n=42) and others (n=8).The initial selection of subjects for this study was made based on the primary schools’ teachers’ ability to respond adequately to the questionnaire that requires the subjects to reflect their views towards the teachers’ level of multiculturalism. Teachers completed the demographic information and the Personal Multicultural Assessment. The survey took approximately 25 minutes to complete, on average. MeasureThe survey instrument used and modified specifically for this study was the Personal Multicultural Assessment by Moore (1995) to measure primary schools’ music teachers’ level of multiculturalism in terms of life experience, personal attitudes, personal behaviour and professional behaviour. This instrument consisted of 32 items, which are divided into four subscales: (a) life experience; (b) personal attitudes; (c) personal behaviour; and (d) professional behaviour. There are eight items in each subscale for analysis. Each item was a multiple choice format with five choices, consistent with the five personae created to match the points on the scale. Questions one to eight presented context phrases with five possible responses, reflecting the five construct levels as they pertain to personal life experience. Questions nine to 16 presented attitudinal prompts, each with five possible responses, paralleling the same levels. Questions 17 to 32 addressed personal and professional behaviours, utilizing scenarios and choices of five probable behaviours, reflective of five levels. The scale used in Personal Multicultural Assessment is unilinear, a continuum with five established points, showing progress from least multicultural to most multicultural (Moore, 1995). Ebel and Frisbie (1991) support the use of multiple-choice items for such survey objectives. Moore (1995) further states that the authors believe that multiple-choice test items are most adaptable to the measurement of knowledge, understanding, and judgment. Data AnalysesThe data collected from the Personal Multicultural Assessment was compiled and analyzed using quantitative measures. The sorted data were evaluated using means and standard deviations.The 32 items from the Personal Multicultural Assessment are assigned with numerical values based on the chosen answer level in which values of one through five were assigned to each of the five possible answers for each item, representing the five multicultural construct levels within the instrument and were scored as continuous data.Each of the four subscales, life experience, personal attitudes, personal behaviour, and professional behaviour, consist of eight items. Therefore, each subscale had the potential score of a minimum score of 8 and a maximum score of 40. The composite score for the entire instrument could range from 32 to 160. Means and standard deviations were computed for each of the subscale scores and the composite score.

3. Results

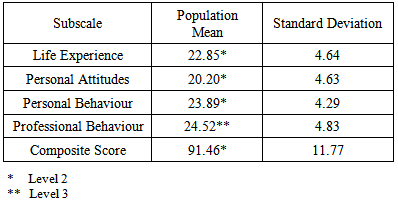

- Table 1 shows the mean scores for each subscale of the Personal Multicultural Assessment for the teachers in this study. All subscales (life experience, personal attitudes, personal behaviour and composite score) fall at Level 2 on the construct except professional behavior which falls at Level 3. Multicultural Personae Construct Level is shown in Table 2.

|

|

4. Discussion

- i. Life ExperienceThe results for life experience fell in the range of 16 to 23 with a mean score of 22.85. It was ranked at Level 2 in Personal Multicultural Assessment. It was in line with previous researches findings (Moore, 1995; Randal, Aigner & Stimpfl, 1994, 1995; Petersen, 2005) that utilized the same instrument. In life experience subscale, it addresses the opportunities to interact with other groups of ethnic and culture. Individual at Level 2 has started to question negative stereotypes and has positive viewpoints in ethnic diversity. Besides, the results also showed that the primary schools’ music teachers recognize complexity of cultural difference and may continue to become more culturally sensitive. As Moore (1995) states, life experience is a core concept of social developmental from a developmental perspective. Butler, Lind and McKoy (2007) further argue that the more experiences teachers have in knowing about how their own cultural backgrounds and ethnic identities influence their attitudes about other cultural groups, the more open they may be to recognizing the significance of culture and ethnicity as factors critical to teaching and learning.ii. Personal AttitudesThe mean score for personal attitudes was the lowest among the four subscales. But it was seen otherwise in the previous studies (Moore, 1995; Randal, Aigner & Stimpfl, 1994, 1995; Petersen, 2005) where the mean score for life experience was the lowest among all subscales. However, personal attitudes was ranked at Level 2 in this study, same as life experience subscale. This reveals that, attitudes may be at a higher level possibly due to education, moral and cognitive maturity even though one has limited intercultural experiences. At this level, individuals are having positive exposure to people from other cultures. Their predisposition attitudes are unstable so they are susceptible to change, and the stability of prejudicial attitudes be challenged as one has positive exposure to people from other cultures (Moore, 1995). The degree of exposure to different cultural events and activities can influence the teachers’ cognitive maturity and attitudes towards multiculturalism (Moore, 1995; Petersen, 2005).iii. Personal BehaviourSecond to professional behaviour, personal behaviour’s mean score (23.89) was the second highest of all the four subscales. The same result was also noticed in Moore’s study (1995). As its mean score approaches Level 3 construct, it can be anticipated that primary schools’ music teachers in Malaysia are going through multicultural experiences and gaining relevant knowledge accordingly.iv. Professional Behaviour Professional behaviour has the highest mean score (24.52) than the other 3 subscales is being classified at the third level in this study. This was also noticed in Moore’s study (1995). According to Petersen (2005), individuals at this level are looking at diversity and interact with others in terms of cultural issues. It is believed that primary schools’ music teachers in Malaysia are making observable changes in behaviour, and actively seeking exposure to new information and new situations.v. Level of Multiculturalism of Primary Schools’ Music TeachersFindings are consonant with the past studies (Moore, 1995; Randall, Aigner, & Stimpfl, 1994, 1995), when being assessed by the Personal Multicultural Assessment, the primary schools’ music teachers were ranked at Level 2 construct according to the Personal Multicultural Development Scale. Level 2 individuals have the following characteristics:• begins questioning negative stereotypes;• has meaningful and/or positive exposure to ethnic diversity;• recognizes complexity of cultural difference;• begins to question own views of different cultures;• feels legitimate challenge to cultural views;• affected by new cultural ideas, but does not act on them.The results revealed that the primary schools’ music teachers in Malaysia have started to doubt negative stereotypes and welcome ethnic diversity. As they recognize the complexity of cultural differences, they begin self-questioning about their own views in this scope. Moreover, they are exposed to new cultural ideas and being challenged by different cultural views. Perhaps the music teachers are living in an environment where they are given an opportunity to be exposed to and interact with cultures and music different from their own. Given this opportunity, their attitudes toward multicultural music education would be influenced to a certain extent. A person’s multiculturalism can be elaborated by looking at his/her increase of mean scores for all the subscales in the Personal Multicultural Assessment relative to the multicultural constructs (Petersen, 2005). Nonetheless, primary schools’ music teachers in Malaysia would have higher levels of multiculturalism when their mean scores of professional behaviour increased; but seemed otherwise when it comes to personal attitudes and personal behaviour.The inter-relationships between the four subscales in the Personal Multicultural Assessment and the gradual increase in the means across the subscales support the developmental theory within the assessment constructs. Multiculturalism is a multi-dimensional process, and the music teachers may function simultaneously at different levels across various situations. Hence, it can be said that even though they could perform better levels of multiculturalism through their professional behaviour, but their levels of multiculturalism seemed poor through their personal attitudes and personal behaviour. Another way to explain about this is that the music teachers need to perform professional behaviour in order to comply with all the codes of conduct as far as their profession required them to. In other circumstances or situations where codes of conduct are not related, the teachers might act differently which were noticed under the results correlated to their personal attitudes and personal behaviour.Consistently setting up a good example in reputable multiculturalism amongst teachers is essential as it can directly influence and motivate students to become multi-culturally sensitive and positive (Moore, 1995).

5. Conclusions

- Malaysia, being a multicultural country, there is a need to inculcate the spirit of multiculturalism in every nation in Malaysia. Given the above scenario in Malaysia, it is quite evident that there is still room for improvement in all levels of multiculturalism amongst primary schools’ music teachers. Anna (2009) noted that many efforts have been made by the Malaysian government to address issues of national integration especially amongst the different ethnic and cultural groups, however the positive results remain to be seen. Thus, it is critical for authorized parties to examine what is really happening on the ground and what needs to be done to ensure music teachers are developing more critical and deeper understanding about multiculturalism. In order to maintain national integration in Malaysia, there are many kinds of efforts have been taken by the Malaysian government to promote music teachers’ positive beliefs and attitudes towards diversity, such as teacher training programs evaluation and teachers’ openness enhancement, together with teachers’ self-reflective abilities commitment to social justice and positive intercultural experiences. With this, it is hoped that the various cultural communities in Malaysia could live alongside each other while maintaining their own original identities.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML