-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2014; 4(2): 24-28

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20140402.02

Quality of Professional Life of Special Educators in Greece: The Case of First-degree Education

Christodoulou Pineio1, Soulis Spyridon-Georgios2, Fotiadou Eleni1, Stergiou Alexandra3

1Department of Physical Education & Sports Science, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

2Department of Primary Education, University of Ioannina, Greece

3Department of Medical School, University of Ioannina, Greece

Correspondence to: Christodoulou Pineio, Department of Physical Education & Sports Science, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The quality of professional life is the degree in which an individual has positive feelings about his/her work or his/her work environment. It is reported to the positive situation or the sentimental attitudes that they can gain the people through their work. Regarding to the bibliography about Greek first-degree special educators, there are a few necessary elements for professional life quality. The present study focuses on the above investigation subject. More specifically, this study investigated the relation of labour satisfaction, professional exhaustion and secondary traumatic stress with gender, age, years of previous experience, the familial situation, and the number of children that the teacher supports on a daily basis, as well as the relation of three dimensions of professional quality of life among each other. The research sample is consisted of 118 special education teachers (N = 118) of first-degree education. ProQOL (version 5, 2009) was used as a psychometric tool for the evaluation of the quality of professional life. The statistical parcel of SPSS, version 20.0, was used for the statistical data analysis. A statistically significant relation was realised between the secondary traumatic stress and the number of students, between the secondary traumatic stress and the teacher’s familial situation and between the secondary traumatic stress and special educator’s gender. Also, statistically significant relation was realised among the professional satisfaction and teacher’s age, the professional satisfaction and the number of students. Furthermore, between the professional exhaustion and the number of students and between the professional exhaustion and the teacher’s gender, was a statistically important relation.

Keywords: Quality of professional life, Professional satisfaction, Professional exhaustion, Teachers of special education

Cite this paper: Christodoulou Pineio, Soulis Spyridon-Georgios, Fotiadou Eleni, Stergiou Alexandra, Quality of Professional Life of Special Educators in Greece: The Case of First-degree Education, Education, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 24-28. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20140402.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Quality of professional life is the satisfaction or the dissatisfaction that somebody feels and experiences in combination with his/her work [1]. The dimensions of the quality of professional life are: professional satisfaction, professional exhaustion, and secondary traumatic stress [1].Locke ([2], and [3]) connects the satisfaction and the dissatisfaction from work with the individual’s system of values: “Professional satisfaction is a positive sentimental reply to the particular work that springs from the estimate which provides fulfilment or allows the fulfilment of individual’s labour values” [3].Professional satisfaction is influenced by individual, social interpersonal, organisational and institutional factors. These factors, which are known as “sources of satisfaction” [6], are related either to the content of work or to the frame in which the work is provided. It is a result of a worker’s estimate that concrete work satisfies his/her needs and reflects the total worker’s attitude towards the work by his/her values and expectations ([4], and [5]). Professional satisfaction plays an active role in how much the individual attributes in their work [7]. Moreover, a lot of studies show that labour satisfaction influences the emotional and physical well-being of a subject ([8], and [9]), as well as many operations of an individual’s daily life [10].Specifically, professional satisfaction is characterized by a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, dedication, absorption, high levels of energy and mental resilience while working. Certain demographic variables, for example, age, sex and work profile have been proven to constitute defining factors of the satisfaction level from work. Professional exhaustion or burn-out is defined as a consequence of intense physical, affective and cognitive strain, as a long-term consequence of prolonged exposure to certain demands. Burnout is a psychological syndrome that may emerge when employees are exposed to a stressful working environment, with high job demands and low resources [15]. Furthermore, the researchers define professional educational exhaustion as a syndrome that is constituted by three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, impersonality, and the decreased feeling of personal achievement ([12], [13], [14], [15], and [16]), dimensions which are observed during the worker’s adaptation effort in the daily difficulties of his/her professional activity. Emotional exhaustion constitutes the “heart” in this particular syndrome [11]. Most researches agree that burned-out employees are characterized by high levels of exhaustion and negative attitudes towards their work.Secondary traumatic stress is defined as work‐related, secondary exposure to people who have experienced extreme or traumatic stressful events. The negative effects of secondary traumatic stress may include fear, sleep difficulties, intrusive images, or avoiding reminders of the person’s traumatic experiences [1].Many researchers support that professional exhaustion does not suddenly present, but is the result of a long period of stress [11]. It appears when the individual him/herself is in emotional inopportune situations for a long period of time [17]. It presents as a professional, natural evacuation and as emotional exhaustion [18].Particularly individual’s 30−40 years of age, unmarried men, and finally highly educated individuals are “prone” to professional exhaustion [19].Healthcare workers and workers of any kind, including students, are often prone to Professional exhaustion. It is given that professional exhaustion mainly affects individuals who practise professions in which communication and interaction with a person-citizen, student or patient are basic elements [1].The teachers practising an eminently humanitarian profession are often in conditions of intense stress and are often led to professional exhaustion ([1], and [17]). More specifically, teachers who work at special education schools face bigger danger to be professionally exhausted. Sources of professional stress of special education teachers have been located by research on the organisational subjects: the professional interactions [20], the lack of teacher’s suitable professional education and specialisation; the difficulties in the satisfaction of infirmity children needs; school failure, which in the particular case is more frequent than success; the unreal and high expectations for student progress that is erroneously placed on the teacher ([21]; the lack of time; the work pressure; the improper student behaviour [22]; the work conditions in the Greek schools of special education; and the enormous reserve of patience and mental force that is required.International research has indicated that the high levels of stress of special education teachers are related to the responsibilities of their work ([23], [24], and [21]). The intensity of stress that is related to the special education teacher, according to the research, varies from one culture to another or from one country to another. These fluctuations can be attributed to different social-cultural and educational frames, to the measurement instruments, and to the research methods. The teachers who are characterized by professional exhaustion negatively affect themselves [17], their students and the educational system [25]. Therefore, they use less energetic learning and provide less positive aids to their students [26]. As mentioned above, this study attempts to present research that aims to:• investigate the relation between dependent variables: labour satisfaction, professional exhaustion and secondary traumatic stress with independent variables: sex, age, professional specialisation, years of previous experience, familial situation and the number of children that the special education teacher supports on a daily basis and• investigate the relation among three dimensions of the quality of professional life.

2. Method and Procedure

2.1. Sample

- The research sample was consisted of 118 special education teachers in first-degree education, who work in special education schools in Thessaloniki, Etoloakarnania and Ioannina (Greece).

2.2. Data Collection Tool

- The research was based on the Professional Life Quality: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue (ProQOL; version 5) questionnaire by Hudnall Stamm (2009) (process of reverse translation).This particular questionnaire constitutes a significant psychometric tool in the inquiring process, but also in clinical practice with widespread use. Overall, it includes 30 questions that are addressed to professionals of special education and evaluates three dimensions of professional quality of life.Before issuing the above-mentioned questionnaire the teachers were given a preliminary questionnaire on the collection of certain essential demographic elements and information.

2.3. Process

- The questionnaires were mailed out with stamped, self-addressed envelopes for return. Reminder telephone calls provided a 100% response rate.

3. Findings

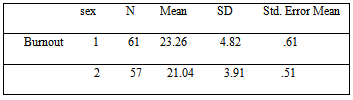

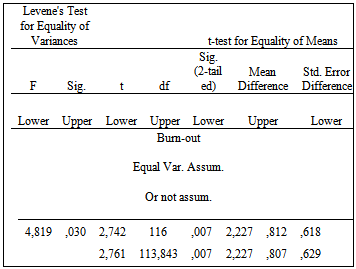

- The statistical parcel of SPSS 20.0 was used for treatment and statistical data analysis. The sample follows regular distribution (n =118>30, and regularity test Kolmogorov - Smirnov).A T-test was used to investigate the relation among the dependent variables: professional exhaustion, professional satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress and the independent variables: sex, previous experience of teacher’s in structures of special education, number of students per special educator, and teacher’s familial situation. A one-way ANOVA test was used to investigate the relation among the dependent variables: professional exhaustion, professional satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress and independent variable: age-related group of special education teachers. An analysis of bivariate cross-correlation (linear bivariate correlation) was used for the investigation of the relation among three dimensions of professional life (quality professional satisfaction, professional exhaustion, and secondary traumatic stress).The investigation of the relation between the professional exhaustion and teacher’s sex resulted in a statistically significant relation, Sig.=.00<.05, because the observed level of statistical importance is smaller than the theoretical (table 2). Men special educators expressed more professional exhaustion (M=23.26, S.D=4.82) compared with colleagues women special educators (M=21.04, S.D.=3.91) (table 1).

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The aim of this research was focused on exploring the quality levels of Special Educators’ professional life in Greece.The results of this study are confirmed by the results of previous similar research ([27], [28], [29], [30], and [31]) and they are not individually confirmed. More specifically, the results show that teachers of first-degree special education in Greece present high levels of professional satisfaction, low levels of professional exhaustion and low levels of secondary traumatic stress. According to Stamm [1], this is the most ideal combination between the three dimensions of professional quality of life. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, an important statistical relation was realised between the secondary traumatic stress and number of students per special education teacher, secondary traumatic stress and teacher’s familial situation, secondary traumatic stress and sex of special education teacher, professional satisfaction and teacher’s age, professional satisfaction and number of students per special education teacher, professional exhaustion and number of students per special education teacher, professional exhaustion and teacher’s sex.The finding that the relation between professional exhaustion and special education teacher’s sex is statistically significant also confirms the research conclusions of Chris (1989), but does not confirm the research conclusions of Billingsley and Cross ([24], and [32]).The discovery that the relation between professional exhaustion of special education teachers and their familial situation is not statistical significant confirms the conclusions of research studies carried out by Kokkinos and Davazoglou ([33], 28], and [12]).The result that the relation between professional exhaustion of special education teachers and age is not statistically significant confirms the research carried out by Chris [22].Also, the finding that the relation between professional exhaustion of special education teachers and years of previous experience is not statistically significant confirms the relative conclusion of Chris’ [22] research. Furthermore, the conclusion from the investigation of the relation between the professional satisfaction and sex, confirms the research conclusions of Eisenger [34].However, this study does not confirm the conclusions of research studies by Byrne [35], Kantas [28] and Sari [36], which show that women draw greater satisfaction from their work than their male colleagues. The result of the present study between secondary traumatic stress and the previous experience of special educators in first-degree education did not result in a statistically significant difference and does not confirm the conclusions reached by Fogarty et al. [37], Kokkinos and Davazoglou [33], and Platsidou and Agaliotis [38]. Moreover, the finding that the experienced special education teachers present low stress levels confirms the research conclusions of Kokkinos and Davazoglou [33], and Platsidou and Agaliotis [38].This study notes that the best way to address professional exhaustion syndrome is prevention. Because, the professional exhaustion is associated with a lower effectiveness at work, a decreased job satisfaction and a reduced commitment to the job or the organization. It is associated with intention to leave one’s job. Consequently, it is suggested that preventive measures and interventions are implemented at the organisational level as much as the individual level, in order for special education teachers to continue being satisfied and to continue offering high quality educational work to disabled children. It is suggested that the quality of instructive work is influenced by the satisfaction that a teacher draws from his/her profession, not only as satisfaction from his/her work, but also as satisfaction from his/her career [39].The professional teacher’s satisfaction is connected to the quality, the effectiveness and the stability of their educational work, as well as their productiveness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Greek State Scholarships Foundation (I.K.Y.).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML