-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2013; 3(6): 294-302

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20130306.03

Pragmatics and Aesthetic Reading: From Theory Based Analysis to an Analytic Framework

Kim L. Lium, M. Alayne Sullivan

School of Education, University of Redlands, Redlands, CA, 92373

Correspondence to: Kim L. Lium, School of Education, University of Redlands, Redlands, CA, 92373.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This article is based on a qualitative phenomenological case study that sought to establish a framework and analytic tool derived from a close theoretical reading of Rosenblatt’s (1978) text. The study took place on a middle school campus in southern California with five participants who were all sixth graders in a bound system. The analytic tool was used to analyze the literature-based responses of 11-and-12 year old resistant readers in order to determine the extent of their ability to engage in aesthetic reading transactions as per Rosenblatt’s (1978) hallmark work. We found that inexperienced, resistant readers are able to read aesthetically at modest levels as revealed through this research. Given the complexity of processing entailed in aesthetic reading, this important discovery holds significance for scores of struggling students who can be nourished as readers through a literature-based approach rather than the strict skill-based ones dominating schools at this time.

Keywords: Aesthetic Reading, Literary Reading, Struggling Readers

Cite this paper: Kim L. Lium, M. Alayne Sullivan, Pragmatics and Aesthetic Reading: From Theory Based Analysis to an Analytic Framework, Education, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 294-302. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20130306.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction and Background

- Many of the students in our 21st century schools and classrooms are experiencing a disconnect between their school experiences and their lives, and all too often have come to view reading or their English classrooms as places where stories are read and summarized, and questions are answered, leaving by the wayside the experiential transaction and opportunity for life connections and social consciousness. According to Banks[1], “when school fails to recognize, validate, and testify to the racism, poverty, and inequality that students experience in their daily lives, they are likely to view the school and the curriculum as contrived and sugar-coated constructs that are out of touch with the real world and the struggles of their daily lives” (p. 18). Often, these students who are experiencing this disconnect become resistant readers and resistant learners. Some students are resistant simply because they do not see purpose or meaning behind the materials they are learning and reading, and therefore view the information as inconsequential and an insignificant part of their lives[1-4]. Others face resistance to learning and reading due to limited access to materials[5], reading difficulty[6], and motivation[7]. Ultimately, this disconnect between the curriculum and resistant learners has served to perpetuate an extreme disparity between the privileged and the underprivileged, as well as condoning and maintaining the dominant monocultural canon and the status quo in our schools and our society. According to Rosenblatt[8-10], because we are teachers of literature, it is our primary responsibility to foster and support personally meaningful transactions and experiences between readers and books. Through these personally meaningful transactions, resistant readers are given the opportunity to grow as individuals when they explore literature that is relevant to their worlds as well as literature that seeks to explore the worlds of others. As Rosenblatt[9] further asserted, “our classroom atmosphere and the selection of reading materials should be guided by the primary concern for creating a live circuit between readers and books” (p. 66). This live circuit should generate excitement, engagement, and interest between the reader and the world they are exploring in the literature they are reading. We posit that it is the students whose reading lives are most depleted of engaging experiences who should be most enriched by school literary engagements that enthrall the mind with intricate processing, deep explorations, and mindful play with absorbing depths of literary reading.

1.1. Why Aesthetic Reading and why now?

- As Alvermann[11] contended, our classrooms and current definition of what it means to be literate is a very narrowly constructed definition that leaves cultural practices by the wayside. Some students are deemed literate because they can assimilate to the academically structured literacy world, while others are labeled as struggling or resistant because they simply do not understand the purpose and they do not identify themselves as a part of the currently defined, traditional literacy world. As Alvermann[11] further maintained, the literacy we are providing our students is “functional literacy, meaning literacy that makes a person productive and dependable, but not troublesome” (p. 99). This is a second-rate type of education that leads directly to lower expectations and to severe social injustices and inequalities. Greenleaf and Hinchman[6] contended that problems with adolescents and literacy exist because of a “failure in the system to provide much more than cookie-cutter instructional responses that do not address youth’s literacy needs” (p. 11). We hold that it is especially struggling or inexperienced and “low-performing” students who most need schools to help them engage the world around them through literature even as they simultaneously acquire literacy skills through such active processing.Having intricately explored both a detailed and complex profile of a paramount discussion of aesthetic transactional reading (i.e. Rosenblatt’s 1978 presentation,[12]) as well as an in-depth analysis of the intricacies of five “struggling” students’ aesthetic literary engagements, we are able to testify to the comprehensive ranges of this phenomenon and thus affirm its importance in schools. We ignore this work at the peril of students’ academic nourishment.Aesthetic reading entails a genuine transaction between students and literature that is meaningful, conscientious, and deeply comprehensive.

1.2. What is Aesthetic Reading?

- Rosenblatt’s[12] account of aesthetic reading forwards a perspective that has acknowledged a relationship between human beings and their social and natural worlds and has challenged that meaning is not objective and held within the pages of text but rather uncovered through human feelings, connections and experiences. Therefore in the words of Rosenblatt[12], aesthetic reading is an active process with an inner-oriented focus derived from readers and their personal moment-to-moment transactions with a particular piece of literature. In order to have created a lived experience, the reader must pay attention to bits and pieces brought forth such as feelings, attitudes, ideas, situations, personalities and emotions; these connections and experiences are the essence of aesthetic reading. Aesthetic reading becomes what the words of the text are “stirring up” for the reader. As Rosenblatt[12] pointed out, “the distinction between aesthetic and non-aesthetic reading derives from what the reader does, the stance that is adopted and the activities carried out in relation to the text” (p. 27). A classroom environment structured to facilitate the complexities of aesthetic reading must consider particular readers who bring their lives into the classroom and thus who must be respected as engrossing and challenging literature is appropriately selected for them – literature that engages their complex beings and which culls a stance of curiosity, interest and even intense preoccupation.

1.3. Aesthetics and Struggling Readers

- The struggles of adolescent readers have been characterized from multiple perspectives – alternatively as socially constructed and contextually determined[13]; and from outlooks related to interventions for them[14-15]. Franzak’s[2] review of the literature on marginalized, adolescent readers summarizes reader-response approaches, strategic reading approaches, and critical literacy, with varying emphases being undertaken within each of these three paradigms. Guthrie and Wigfield’s[16] work attests to the critical role that engagement plays in the reading and literacy process. Triplett[13] discusses how students’ struggles with reading are socially constructed - greatly influenced by teachers’ reactions, particular school contexts, curricular variables and relationships. This premise is widely accepted and developed by many theorists and researchers who often claim contextual variables as the overarching influence in most teaching and research situations[17-20] (Gee, 2000a; 2000b; 2001; 2002). Then we hear, yet again, Alvermann and Marshall[21] tell us “the term struggling can refer to youth with clinically diagnosed reading disabilities as well as to those who are unmotivated, disenchanted, or generally unsuccessful in school literacy tasks” p. 125). The readers who participated in this study had spent all of their school lives enduring reading programs that attempted to “remediate” them through skills approaches; never had they been engaged in a reading program that had any emphasis such as that taken with them here.

2. Description of Context

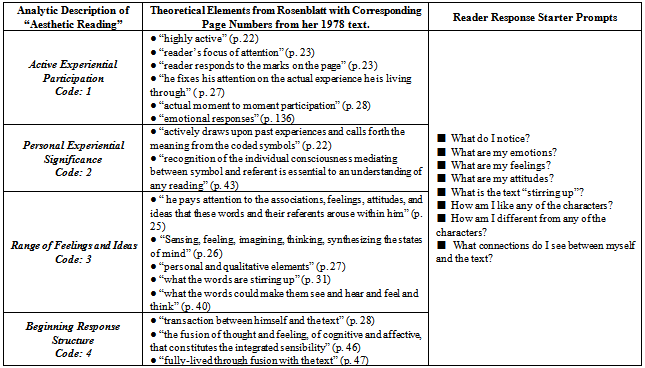

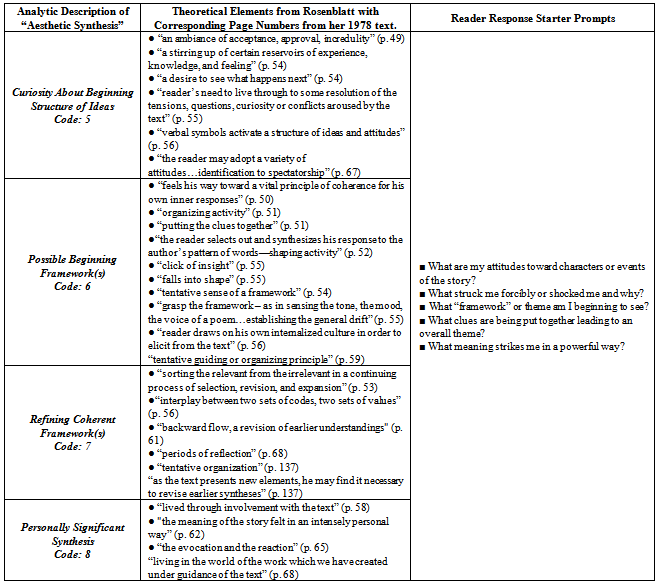

- This qualitative case study research project took place during a three-month period in which five resistant readers read and responded to three texts carefully selected for their themes of multiculturalism and social justice. The texts selected were Number the Stars by Lois Lowry, Day of Tears by Julius Lester and Seedfolks by Paul Fleischman. The participants responded to each text through journals, mid and end of book literary responses, whole class discussions videotaped at least twice per week, and book projects. All five participants also participated in a final interview in which their experiences with the texts, the projects and the classroom environment throughout the three months were shared. The participant’s journals, videotaped discussions and book projects were analyzed line by line using an analytic tool developed from a close analysis of Rosenblatt’s seminal text[12]. In order to develop the analytic tool, Rosenblatt’s text[12] was reviewed and examined for words and phrases used to describe her emphases on (a) aesthethic transaction, (b) aesthethic synthesis and (c) social consciousness. Those words and phrases were then placed into like categories in which a data analysis descriptor statement was generated to describe the category. We next briefly discuss the process that led us to approach Rosenblatt’s text [12] and cull from it an organically faithful rendition of its core moments. As readers, we were sensitive to the elements of her text that signaled: (a) aesthetic reading, (b) aesthetic synthesis, and (c) social consciousness. In turn, we present three tables, each one dedicated to these respective “transactional strands” while at the same time emphasizing that we sought to present this work in a way that did not reduce its richness to isolated fragments. Rather we see the separately highlighted elements as the fabric of a process weave in which individual “threads” coalesce to form a unique fabric of engagement manifested most significantly in our readers’ literary transactions which we also depict in alignment with our respective analysis.Table 1 presents an analytic account, first, of aesthetic reading. Having told us in her chapter 2 that “the text becomes the element of the environment to which the individual responds” and that “[a] person becomes a reader by virtue of his activity in relationship to a text which he organizes as a set of verbal symbols[12, p. 18] we proceed to Rosenblatt’s distinction between efferent and aesthetic reading, the latter being her focus. Paraphrasing her work in this chapter we see an emphasis on a highly active reading process that is cast as an actual experiential, emotional participation whereby the reader draws on past experience as the individual consciousness mediates associations, feelings attitudes and ideas arousing a personal transaction between self and text. A fusion of thought and feeling, of the cognitive and the affective results in a “fully lived-through fusion with the text” (p. 47). In our table, below we offer an analytic phrase in the left-hand column that is aligned with specific phrases from her text in the second column; each of the phrases is associated with a code that is applied to students’ journal responses and transcribed discussions, to be discussed later in this article. In the third column, we present phrases used to prompt possible responses from students that are akin to that of the theoretical description. Table 2 presents an analytic profile of aesthetic synthesis (Rosenblatt’s chapter 4); she tells us that the “awesome complexity of the[aesthetic] process” (1978, p. 49) results in “an organic and vital kind of synthesis” (p. 50). This “synthesizing urge” (p. 51) forms the basis of description for a significant segment of her work. She speaks at length about a reading process that moves beyond aesthetic experience to a desire to resolve the tensions, questions, curiosity and conflicts in a structure of those ideas. The reader, Rosenblatt critically tells us, “feels his way toward a vital principle of coherence” (p. 51) and establishes a “tentative sense of framework” (p. 54) that results in a “tentative guiding or organizing principle” (p. 59). Our table further delineates a myriad of elements that comprise what we see as a stage of the aesthetic reading process that moves toward coherent form. In the students’ projects, the classroom environment was respectful of this stage of the theoretical characterization in that students were encouraged to visually or dramatically represent what they saw as the essential whole of the novels they read; after much discussion students were also asked to comment on what the novel meant or represented altogether for them. Our analytic descriptions are again aligned with distinct theoretical elements and then further complemented by reader response starter prompts in the far right-hand column. This table is meant to depict a stage of the reading process that consolidates or further enriches the initial stages of aesthetic reading that are presented in table 1. Again, numeric codes are aligned with this aspect of the aesthetic reading process; the increased numbers relative to table 1 are meant to suggest that this stage of the reading process becomes more mature.

|

|

|

2.1. Findings

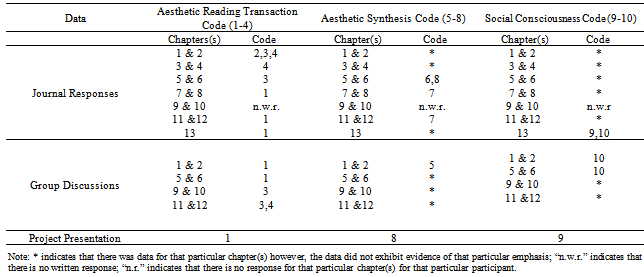

- What emerges from the data is a cornucopia of information about aesthetic reading as we have depicted it in our tables – to reiterate, we distinguished a continuum of responses that evolved from aesthetic reading (codes 1 through 4), to aesthetic synthesis (codes 5 through 8), and individual and social consciousness (codes 9 and 10). Each of the five individual students’ journal responses and small-group discussions was coded (having recorded and transcribed such discussions) for each of the three novels they read: first, Number the Stars (22), second, Day of Tears (22), and third, Seedfolks (23). It is beyond the scope of this article to present a detailed analysis of the each of the students’ analytic profiles but we are able to offer summary statements about patterns revealed. For example, all readers evidenced aesthetic reading across most dimensions (codes 1 through 4); not all readers evidenced all aspects of aesthetic reading as defined for all three books read. Nor is it apparent that as the reading experiences progressed over the twelve weeks of the research did readers necessarily display more complex reading patterns; one might predict that as the weeks unfolded, more and more dimensions of the process might be revealed as the readers gained experience in a style of reading and responding which contradicted the prescribed reading styles in which they had been taught over the previous five years of school. Rather, the exhibited patterns of response seemed to vary in complexity in accordance with books read. For example Callie’s group discussions and journal responses with Number the Stars (read first) displayed aesthetic reading patterns (codes 1 through 4) repeatedly and consistently as was the case when she progressed to Day of Tears (read second), and she maintained the relative continuum of aesthetic reading responses (again, codes 1 through 4) consistently when reading Seedfolks (read third). This is also true of the other readers who we call Kassandra, Aleisha, Jorge and Ramon – none seemed to read “more” aesthetically (as defined) as they moved from one book to another – as the weeks progressed in other words and as they became more and more accustomed to sharing opinions, asking questions, recording journal entries and engaging in small-group and whole-class discussions.Nor did the readers engage aesthetic synthesis (codes 5 through 8) more and more as they read subsequent books. That is, in reading and responding first to Number the Stars through group discussion and journal entries (data for which we have the most quantity and frequency of response) all students manifested about the same volume and quality of statements characterized as aesthetic synthesis (again, codes 5 through 8) with Number the Stars (read first) as with Seedfolks (read last). What we can say is that the medium of group discussion more readily fostered varied elements of aesthetic synthesis than did journal responses. Another way of saying this is to report that when discussing each of the three novels through group discussion, the five readers evidenced varied aspects of aesthetic synthesis across those 4 dimensions more than when responding via journal entry. We must remember, in reading these statements, that this research took place over a 12-week period with struggling, weaker, or resistant readers – those for whom reading was described as least interesting, boring, and not voluntarily engaged in - and that this period of time may not have allowed students to acclimate fully to the unfamiliar practices of open discussion, journaling, and book projects at the conclusion of the reading of each novel. One might expect that if the students had continued exposure to such intensive literary reading, writing, discussion, and varied arts-based projects they would more and more habitually engage a range of such responses.Even further, we can report that almost no student showed evidence of individual and social consciousness (codes 9 & 10) in his/her reading of the initial third of each book read. This pattern is contradicted only by Callie and Ramon who when reading chapters 1 & 2 of Day of Tears evidenced code 10 (compassion and empathy) in their journal (Ramon) and group discussions (Callie) as they read the first two chapters of this novel. For the most part, readers seem to move from aesthetic reading in the relative first third of a novel, toward aesthetic synthesis as they approach the 5th, 6th and 7th chapters, and then toward individual and social consciousness in the latter stages or concluding segments of the novels. This pattern is more or less maintained with each of the five readers with whom we worked. This may be explained, one might initially suppose, due to the order of presentations of the prompts. For example, we have presented within each of our three “stages” of the aesthetic reading continuum differing prompts. But we did not use any specific prompts for students’ journal or small group responses. Though we offer such prompts for teachers who may appreciate having them as they undertake such work, the students who participated in this project were not specifically prompted with any of the starter questions we propose. Thus, that we found a pattern of movement in their responses from aesthetic reading to aesthetic synthesis and then toward the end of the book that they responded with, then, an inclination toward individual and social consciousness seems more a validation of Rosenblatt’s theoretical spectrum than a result of our prompting as the book was read.Having now discussed certain general patterns of the findings among the five respondents, we now turn to a close presentation of one student’s patterns of response, offering “Callie’s” analytic profiles of engagement for Day of Tears (read second). We do this to offer a glance at how the data was analyzed and presented as we moved our way toward the general realizations we have presented above.In her journal for Day of Tears, Callie’s responses throughout the first six chapters showed her responding to the text through Aesthetic Transaction in accordance with what is termed Personal Experiential Significance (code 2), Range of Feelings and Ideas, (code 3) and Beginning Form (code 4). Throughout those transactions she shared opinions of characters, made connections between herself and characters, and made initial attempts to understand the author’s message. An example of her response that showed Personal Experiential Significance was in chapter two when she stated, “I am like Sara is because I don’t like the fact that back in the day there were slaves. I am different from Frances because I don’t like the idea of slaves.” These responses showed a personal connection that she had made with one character while making it clear that she didn’t see herself as being connected with another particular character. Callie also had two instances where her responses fell under the Range of Feelings and Ideas data analysis descriptor (code 3). An example of one of those responses was in chapter one when she stated, “I feel that the darker colored people are treated unfair. I feel that it is not right that people are having slaves.” Through these statements, Callie simply expressed her feelings and attitudes that were aroused by the text in an effort to make meaning. Callie also had two instances when her Aesthetic Transaction responses demonstrated Beginning Form (code 4) where she showed a beginning synthesis of thoughts and feelings that had been building from the beginning of the text. One of these responses occurred in chapter four when she stated, “I think slavery is wrong and I would never enforce it. I also that that Pierce Butler wasn’t even sorry that he sold his slaves, he just wanted money.” This response showed Callie’s ability to synthesize her thoughts and feelings about a main character as well as raise her awareness and consciousness with regard to the meaning behind his actions.In our whole class discussion about chapters nine and ten, Callie stated, “I just wonder why were they slaves for so long and why didn’t they run away and like I would run away too, just like Emma.” This statement falls under the Range of Feelings and Ideas (code 4) data analysis descriptor because she shared her feelings and attitudes about the concept of slavery and she questioned the idea of why the people remained slaves and did not run. The expression of these feelings and attitudes and her questions are all responses that she generated in an effort to make meaning of the text. During our whole class discussion of chapters 11 and 12 she shared, “I picked I’m glad you and Joe got away from slavery but you are in danger here in Philadelphia. I picked this because I think Fanny Kemble is being really thoughtful and trying to help them and saying if they were there and Pierce Butler caught them they would be transferred to someone really bad.” This statement showed evidence of Beginning Form (code 4) because Callie used lines from the text to support her opinions and reactions toward characters in an attempt to merge her thoughts and feelings about what was happening in the text with what the overall message of the book may be. She synthesized her thoughts about the actions of particular characters and referenced them with what the text’s message is about slavery.Moving beyond the Aesthetic Transaction emphasis, Callie also had responses in her journal and in one whole class discussion that illustrated examples of Aesthetic Synthesis. Throughout her journal and our whole class discussions Callie had two responses that were in accordance with Possible Beginning Framework(s) (code 6), two responses that fell under the analysis descriptor of Refining Coherent Framework(s) (code 7), and one response that fell under the analysis descriptor of Personal Significant Synthesis (code 8). Under the Aesthetic Synthesis emphasis, responses become more detailed and more established with what meaning the book created for the reader. An example of from Callie’s journal that illustrates both the data analysis descriptors Possible Beginning Framework (s) (code 6) and Personal Significant Synthesis (code 8) is her response in Chapter six. She stated, “I think slavery is bad. I think everyone has rights and I don’t agree with it. I feel really sad that Emma got sold away from her family. I think that Joe will be a good person to her now. Slavery is wrong because it takes you away from your family and friends. And then you have to work for white people.” This response exemplified her efforts to synthesize the overall meaning of the book as well as express her deep conviction that slavery is wrong. An example from Callie’s journal that demonstrates the data analysis descriptor Refining Coherent Framework(s) (code 7) is when in responding to chapter seven, she shared that she thought the overall message of the book was “struggle.” She wrote, “I think all the slaves struggled being crushed in slave quarters and being whipped and children being sold or just family members and it’s a struggle for Emma and her parents.” Early on in her journal, Callie had referenced the theme or message of the book as slavery and in her response in this chapter she changed her stance and makes it more precise by saying she believed the theme of the book was “struggle.”In addition to Aesthetic Transaction and Aesthetic Synthesis, Callie also demonstrated evidence of Rosenblatt’s (1978) third emphasis of development of Individual and Social Consciousness under the analysis descriptors of Awareness of Self-in-World (code 9) and Compassion and Empathy (code 10). In her chapter thirteen response in her journal in a letter to Emma, a main character, Callie wrote, “Dear Emma, I would like to show you our world today and how people of all races are free, but I would not want you to see that some people can’t get over a blended community and I wish that slavery never happened.” In this response, Callie illustrated her ability to connect the message of the book to her world as well as show empathy and compassion for what the characters in the book experienced. Callie also showed evidence of Aesthetic Synthesis and Social Consciousness in her presentation of her Day of Tears Project. Under the emphasis of Aesthetic Synthesis she demonstrated the analysis descriptor Personally Significant Synthesis (code 2) and under the emphasis of Social Consciousness she demonstrated the analysis descriptor Awareness of Self-in-World (code 9). An example of her demonstration of Personally Significant Synthesis is when she stated, “I chose perseverance as my theme because I think they just really had to persevere in order to get through anything. I also put love on my collage because they have to love each other and persevere through everything and they can’t just step away from it.” An example of her demonstration of Awareness of Self-in-World was evidenced when she explained why she included the words “today’s success” and “slavery” in her collage. She shared, “I put today’s success because you can see people are like famous now like Obama and Beyonce and everybody. I chose slavery because I think that slavery is wrong and I think everyone has rights and I feel really sad that Emma got sold away. Slavery is wrong because you have to work for white people just because you are black.”Callie’s journal responses, responses during whole class discussions, and project presentation all pointed to her aesthetically engaging under all three of Rosenblatt’s (1978) aesthetic reading emphases with the text Day of Tears. This evidence is illustrated in the preceding narrative as well as in Table 4.6 that follows. The coded numbers represent the specific data analysis descriptors Callie engaged while reading Day of Tears. Columns three and four represent Rosenblatt’s (1978) emphases of Aesthetic Synthesis and Social Consciousness. The coded numbers in these two columns also represent the specific analysis descriptors in which Callie demonstrated Aesthetic Synthesis and Social Consciousness while reading Day of Tears. Furthermore, the asterisks (*) that appear in the table indicate that there is, in fact, data for those particular chapters; however, the data does not show evidence of falling under that particular emphasis. The code of “n.w.r.” stands for no written response and the code “n.r.” stands for no response. A participant might not have a written response due to the fact that he or she drew a picture in response to that chapter that doesn’t elicit enough information to be coded with an analysis descriptor. Additionally, a participant might not have a response at all due to the fact that he or she was absent or didn’t complete his or her response to that particular chapter.

|

3. Summary and Conclusions

- We have presented an account of aesthetic reading in light of a theoretical model (Rosenblatt, 1978) and depicted the literary reading processes of one specific reader while also alluding to the analogous patterns of engagement of four other “struggling” readers. We have also discussed the complexities of the background literature on what it means to be a “struggling” reader, casting it as the complex interplay of socio-cultural and linguistic factors that are tied to many layers of social and school contexts. Our five readers and the one reader featured herein are students who school reading lives have not been much vivified by reading methods and materials that have aroused enthusiasm or skill in reading. This changed in the twelve weeks of the case study research we reported on here. We worry that the school reading lives of many, many “struggling” students are toxic. We recommend that students be engaged in readings that elicit the ranges of aesthetic interplay that we have discussed and shown with one reader herein. In both its theoretical description as per Rosenblatt (1978) and what we have seen here in terms of one reader and our schematic framework about aesthetic reading, it need not be an elusive or far-fetched phenomenon. In fact the theoretical and practical elements we have presented show complementarity. That is, we have seen a reader manifest the range of aesthetic reading characterizations outlined in our schematic framework which are the very same elements seen in theoretical characterizations. Then we have seen one reader exhibit these very reading processes as she has engaged one particular novel. Given the dignity accorded readers when they are facilitated ever so modestly toward achieving such processes, it seems dehumanizing not to afford all readers a constant diet of such reading opportunities.The same can be said of aesthetic synthesis and socially conscious aesthetic reading. Readers – young and old and experienced and disenfranchised – ought to be allowed to engage literature that brings them into habits of mind that naturally align with what we have characterized theoretically and schematically. Aesthetic synthesis seems to organically emerge when readers are alive and unselfconsciously engaged in the deeper transport of some literary texts. It is a process that entails significantly complex literary reading. It also follows the more relatively response-oriented beginnings of aesthetic reading with a literary work. That is to say, aesthetic synthesis cannot happen, we submit, without a reading context that allows readers the relative free play of responses and somewhat self-directed attention of aesthetic reading. The two processes though presented separately are seen as deeply related to one another and not meant to be appreciated as isolated at all from one another.Similarly, socially conscious aesthetic reading emerges in a socioculturally sensitive context where aesthetic reading and aesthetic synthesis are fostered, where the teacher is engaged not in teaching these reading skills but as a facilitator of involved reading which has some profound life relevance for the students. The basis for the reading that we have characterized herein was based on texts that were chosen for their supposed inherent attraction readers would have for them. Finally we submit that engaging readers in such engrossing literature will also play its role, given socioculturally sensitive contexts, to elicit aesthetic reading from students. They deserve a genuine opportunity to read with all of the qualities we have characterized - theoretically, schematically and practically. The reading contexts in which teachers and students are so conjoined will be all the more humanizing because of such opportunities.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML