-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2013; 3(3): 178-184

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20130303.06

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Three Conflict Resolution Models in Changing Students’ Intergroup Expectancies and Attitudes in Kenyatta University (Kenya)

Boaz M. Mokaya1, Edward A. Oyugi1, Edward M. Kigen1, Haniel N. Gatumu2, Anthony M. Ireri1

1Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, P.O. Box, 43844, 00100, Kenya

2Department of Psychology, University of Nairobi. Nairobi, P.O. Box 30197, 0010,Kenya

Correspondence to: Boaz M. Mokaya, Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, P.O. Box, 43844, 00100, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Rapid changes in university structure and mission present various conflicts that require effective management. This study evaluated the effectiveness of distributive bargaining, integrative bargaining, and interactive problem solving models of conflict resolution in facilitating positive change in student’s intergroup expectancies and attitudes. 120 undergraduate students of Kenyatta University took part in the study. Data were collected using questionnaires and oral interviews. The findings revealed that conflict resolution approaches that increase optimistic expectancies and perceptions of greater compatibility between the positions, interests, and needs of disputants may be more useful for a wide range of conflicts. Recommendations for practice and further research are given.

Keywords: Conflict Resolution Models, University Students’ Attitudes, Intergroup Expectancies, Kenya

Cite this paper: Boaz M. Mokaya, Edward A. Oyugi, Edward M. Kigen, Haniel N. Gatumu, Anthony M. Ireri, Evaluating the Effectiveness of Three Conflict Resolution Models in Changing Students’ Intergroup Expectancies and Attitudes in Kenyatta University (Kenya), Education, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 178-184. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20130303.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- During the last decade, rapid global changes in the mission and structure of institutions of higher learning have been witnessed[1]. In the Kenyan educational system, universities have expanded through establishment of satellite campuses, increased admissions, started double intakes; introduced self-sponsored parallel programmes and embraced diversity among other changes[2-4]. A welcome development is that majority of the Kenyan universities have started courses and research programmes in the areas of mediation, negotiation, and related processes. This is a timely intervention by the institutions of higher learning following the 2007/2008 post election violence witnessed in different parts of Kenya. The changes in the universities have come about in response to changes in the Kenyan society. For example, following the Kenyan Government’s introduction of Free and compulsory primary education and subsidized secondary education, the past decade has witnessed a consistent increase in the number of high school leavers who attain the cut off mark for university admission. In response to this, most public universities in Kenya have embraced the practice of double intake. This in itself has led to a surge in university student population that is not matched by pertinent changes in the human and other resources in the universities. Thus the double-intake has led to most universities having increased student: staff ratios, higher operational costs and pressure on resources (both human and structural). The challenges attendant to these changes have brought about a wide range of university-based conflicts and the need for effective ways of conflict resolution[5]. This study reviewed causes of conflict in Kenyanuniversities, forms of conflict in education, conflict resolution in education, models of conflict resolution in academic setups and evaluated the effectiveness of distributive bargaining, integrative bargaining and interactive problem solving models of conflict resolution in facilitating positive change of group expectancies and attitudes.

1.1. Causes of Conflict in Kenyan Universities

- Over the last two decades or so, there have been outbreaks of violence in the community as well as in universities and schools[6]. In their report, Omari and Mihyo[7] assert that it is easy to see the causes of student struggles as a manifestation of the destruction and decline of academic authority, the weakening of state power, and the politicization of intellectuals. The causes of student unrest can readily be adduced to psychological and sociological theories of alienation, rejection of parental authority, fear of adulthood, disenchantment with human societies;apprehensions about loss of comradeship, freedom, protection and identity at graduation, as causes of the unrest[4, 8-9]. A 2006 research into the causes of violence in Kenyan universities indicated that there was no single cause[10]. The findings indicate that the violence was complex and multilayered and it was generally rooted in student and staff politics, discontent with institutional structures, governance systems as well as environmental and wellbeing issues. Earlier, Musembi and Siele[11] asserted that the disturbances in Kenyan learning institutions mainly arose due to unresolved conflicts between the students and the administrators. Such disturbances are witnessed even in high schools[12]. Khaminwa and Nyambura[10] note that it is difficult to adequately handle the divergent interests systematically and with a degree of coherence since the complexities of university-based conflicts are compounded by untidiness. Mistrust, fear, and lack of transparency dominate student-administrator relationships andinteractions. As noted by McNamara[13] getting the most out of diversity often involves contradictory values, perspectives and opinions.

1.2. Forms of Conflict in Education

- Some of the emergencies that arise as a result of unresolved conflicts include: arson attacks, riots and violence which result in injury and loss of life and property. It is also widely acknowledged that violence against teachers, other students, and destruction of property both in the learning institution and surrounding communities has greatly increased in the past years[9, 12].

1.3. Conflict resolution in Education

- Conflict resolution in education includes any strategy that promotes handling disputes peacefully and cooperatively outside of, or in addition to, traditional disciplinary procedures. The rise of violence and disciplinary problems, along with an increasing awareness of need for behavioral as well as cognitive instruction, spurred the development of conflict resolution programs in schools in the USA during the 1980s. These programs eventually received international attention.Conflict resolution programs differ widely in terms of who participates, the quantity of time and energy they require, and levels of funding they receive. Funding is usually provided by an outside source such as the state, a university program, or a local non-profit organization. Programs can be classroom-wide, school-wide, or district-wide, and can include any of the following components. First, curriculum and classroom instruction, second, training workshops for faculty, staff, students, and/or parents in conflict management skills, negotiation, and mediation, third, peer education and counseling programs where students either train each other in conflict resolution skills and/or actually carry out dispute resolution, and finally, mediation programs in which students, staff, or teachers carry out dispute resolution.

1.4. Models of Conflict Resolution in Academic Setups

- a) Distributive BargainingThe distributive bargaining model originated within the field of labor negotiations[14-15]. Also referred to as "hard bargaining," distributive bargaining is a competitive, position-based, agreement-oriented approach to dealing with conflicts that are perceived as "win/lose" or zero-sum gain disputes. The negotiators are viewed as adversaries who reach agreement through a series of concessions[16]. The objective of distributive bargaining is the maximization of unilateral gains, and each party is trying to obtain the largest possible share of a fixed pie. Gains for one party translate into equal losses for the other. The process involves such tactics as withholding information (e.g., the party's "bottom line"), opaque communication, making firm commitments to positions (a.k.a., "power positioning"), and making overt threats.This model differs from the integrative bargaining and interactive problem solving models in two fundamental ways: (i) the single aim of the negotiator is to maximize self-interest, and (ii) the two parties in conflict interact with each other as though they have no past history or future involvement[17].b) Integrative BargainingFirst conceptualized by Follett[18], the integrative bargaining model also primarily evolved within the field of labor negotiations[15, 19]. It is a cooperative, interest-based, agreement-oriented approach to dealing with conflicts that are intended to be viewed as "1/2 win-1/2 win" or mutual-gain disputes. It is an expanded-pie model, in that it looks beyond the existing resources, aiming to expand the alternatives and increase the available payoffs through the process of joint problem solving. Negotiators work to increase the sum as well as to distribute it. This approach is currently one of the most frequently used models of conflict resolution[20-21].The integrative bargaining process involves both concession making and searching for mutually profitable alternatives. Simply stated, it enables negotiators to search for better proposals than those explicitly before them. From this perspective, negotiators are viewed as partners who cooperate in searching for a fair agreement that meets the interests of both sides[16]. Some common integrative bargaining techniques include clear definition of the problem, open sharing of information, and exploration of possible solutions. This approach encourages the generation of, and commitment to, workable, equitable, and durable solutions to the problems faced by the parties. The preferred outcome of this model is one of maximum joint gains.c) Interactive Problem SolvingInteractive problem solving is a form of third-party consultation, or informal mediation that is generally used by scholar-practitioners. It is a transformation-oriented, needs-based approach to resolving conflict that originated within the field of international conflict resolution[22]. It emphasizes analytical dialogue, joint problem solving, and transformation of the conflict relationship. It is designed to facilitate a deeper analysis of the problem and the issues driving the conflict, including an exploration of the underlying motivations, needs, values, and fears of the parties that are related to their different identities. Interactive problem solving may be most appropriately conceptualized as a process that prepares conflicted parties for diplomatic negotiations (e.g., a pre-negotiation phase) or as an adjunct to traditional techniques (e.g., a para- and post-negotiation process), providing antagonists with an opportunity to engage in conflict analysis and creative problem solving before they become involved in difficult and binding negotiations.The interactive problem solving model begins with an analysis of the needs and fears of each of the parties and a discussion of the constraints faced by each side that make it difficult to reach a mutually beneficial solution to the conflict. One of the goals is to help the parties perceive the conflict as a problem to be jointly solved, rather than a fight to be won. Other goals include improving the openness and accuracy of communication, improving intergroupexpectancies and attitudes, reducing misperceptions and destructive patterns of interaction, inducing mutual positive motivations for creative problem solving, and ultimately, building a sustainable working relationship between the parties. This model is less focused on directly helping parties reach binding agreements and is more devoted to improving the process of communication, increasing perspective taking and understanding, and enabling the parties to reframe their substantive goals and priorities, and ultimately, to engage in more creative problem solving.The interactive problem solving model is assumed to be most appropriately applied to conflicts that involve underlying unmet needs for identity (e.g., security, recognition, and belonging) that are often the roots of ethnic clashes[22]. The key difference between this model and the first two models is that it addresses the substantive issues of a conflict from a more social psychological perspective. Interactive problem solving recognizes and addresses the importance of expectancies and attitudes in perpetuating and escalating protracted conflict and attempts to address the underlying needs and fears of the parties in order to create a transformed, mutually beneficial continuing relationship. This social psychological component is largely absent from the other models.d) How the conflict resolution models workThe workings of the three models for conflict resolution are based on the two primary differentiating features of the models: instructional framing and outcome orientation. The instructional framing of the different approaches refers to the level of conflict analysis (i.e., emphasizing positions, interests, or needs and fears) that is prescribed by each of the models. In distributive bargaining, the parties focus their dialogue on the positions held by each of the parties. Positions can be understood as the stances the parties take on the issue; they are usually conclusions reached by each party that express their preferences as to how the issues of the conflict should be resolved[23]. In integrative bargaining, focus is on the interests of the parties, which can be defined as the perceived reasons why the parties hold the positions they have taken[23]. Interests have also been defined as the preferences or utilities that each person has for the resources to be divided[24]. Interactive problem solving encourages a needs-based analysis of the conflict, focusing on the human needs and fears of both parties. Needs may be defined as he deeper physical, social, or psychological interests and concerns that drive the parties to take the positions that they take[23], such as the needs for identity, security, belonging, and justice[25]. Few theorists have made an effort to identify and separately define these levels of analysis; consequently interests and needs have been used interchangeably in most negotiation theories, even though they may represent distinctly different motivational orientations.The second differentiating feature guiding theoperationalization of these three conflict resolution models is the outcome orientation: whether the approach is agreement-oriented or transformation-oriented (such that the goal is to transform the conflict relationship). Distributive bargaining is completely agreement-oriented, meaning that the goal of the dialogue is to strike an agreement to achieve some sort of full or partial settlement of the conflict. Although integrative bargaining utilizes a very different approach than distributive bargaining and does seek to maintain a functional relationship between the parties, it is also an agreement-oriented approach to conflict management. As mentioned earlier, interactive problem solving is a transformative model that is most concerned with helping the parties engage in a deeper analysis of the problem, focusing on the needs and fears of both sides, and facilitating creative joint problem solving based on this deeper understanding of the causes and dynamics of the conflict. There is no expectation that the individuals participating in interactive problem solving should reach a binding agreement by the end of the dialogue[13, 22]. However, it is hoped that the new learning, insight, understanding, and ideas for a resolution generated in interactive problem solving workshops will then be fed back into the resolution processes of the disputing individuals, providing leaders and decision makers with new ways of thinking about and approaching the conflict.To date, little research has been conducted to evaluate empirically and compare the outcomes of multiple models of conflict resolution. In a comprehensive review of negotiation and mediation, Lewicki, Weiss, and Lewin[26] state that there has been a failure of researchers to test models empirically. They assert that the pattern in research development has been to either propose a general model or to conduct one or more empirical studies that manipulate several selected variables. Although Machingambi and Wadesango[27] recommend that university administrators and academics should seek to embrace open systems where everyone is let to air their views and the areas of conflict discussed openly, the models that can enhance such an approach have received little or no direct research validation or challenge.It is with the foregoing in mind that this study was designed to evaluate the distributive bargaining, integrative bargaining, and interactive problem solving models of conflict resolution, using intergroup expectancies and attitudes as dependent measures.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

- 120 undergraduate students of Kenyatta University took part in the study. Only those students who had stayed at the university for more than one year were involved.

2.2. Data Collection

- In this study, data were collected through a written questionnaire. The students were informed individually or in groups of the purpose for the study before being requested to fill the questionnaires. The total number of questionnaires returned after one week was one hundred and twelve an equivalent of a 93% response rate which is an acceptable rate[28].

2.3. Analysis

- Responses to the questions were coded in SPSS according to the following five themes derived from the research objectives and analyzed:a) Expectations held on conflict situations and opponents when there is conflict.b) The disputants’ perceived compatibility of the positions, interests and needs of each other,c) The disputants’ preferred choice of model of conflict resolutiond) Attitudes held on conflict situations and opponents when there is conflict.

3. Results and Discussion

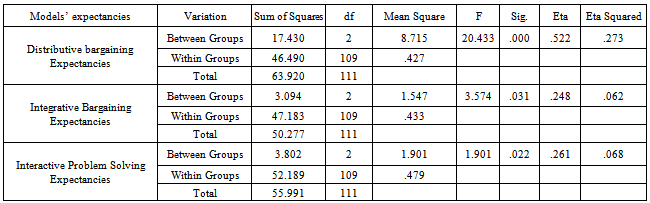

3.1. Grouped Expectancies in Conflict

- We computed one-way ANOVA comparing scores of grouped expectancies of participants who endorsed each of the three conflict resolution models. As shown in Table 1, a significant difference was found among the models: distributive bargaining model (F (2, 109) = 20.43, p<0.05); integrative bargaining model (F(2, 109) = 3.57, p<0.05) and interactive problem solving model (F(2,109) = 1.90, p<0.05). The eta values indicate that the distributive bargaining model explained 27.3% of variance in the conflict resolution action expectancies; while the integrative bargaining and interactive problem solving models explained 6.2% and 6.8 % of the variance respectively.

3.2. Compatibility of Positions, Interests and Needs of Disputants

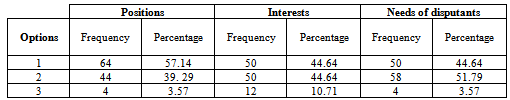

- The students were asked to indicate the extent to which the positions, interests and needs taken by disputants during conflicts are compatible on a 3-Point Scale (1 = Extremely Compatible, 2= Compatible, 3= Not Compatible). As presented in Table 2, majority of the respondents felt that positions, interests and needs of the disputants were compatible either extremely or moderately. Only a few of the respondents rated the disputants’ positions, interests and needs as being non-compatible.

|

|

|

|

3.3. Students’ Preferred Conflict Resolution Model

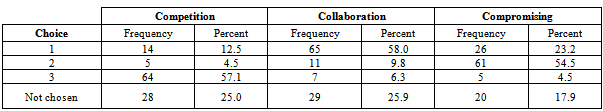

- Students were asked to rank the conflict resolution strategies in order of preference. As shown in Table 3, collaboration was given priority (assigned rank “1”) by majority of the respondents (58%). Only 23.2 % and 12.5 % of the respondents gave priority to compromising and competition respectively. Notably, compromising was ranked second by 54.5% of the respondents. Competition was assigned rank “3’’ by 57.1% of the respondents while the respective percentages for collaboration and compromising at this rank were 6.3% and 4.5%.

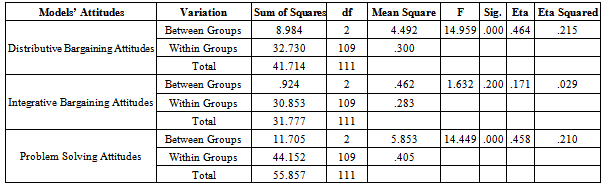

3.4. Attitudes Held in Conflict Situations

- Further one-way ANOVA was conducted on the students’ grouped attitude scores on each of the three models of conflict resolution. The results in Table 4 indicate that significant differences were found among the models: distributive bargaining model (F (2, 109)= 4.49, p<0.05); integrative bargaining model (F(2, 109) = 0.46, p<0.05) and interactive problem solving model (F(2,109) = 5.45, p<0.05. The eta squared values indicate that 21.5% of the variance in attitudes are accounted for by the distributive bargaining model; 21.0% by problem solving model, and a paltry 2.9% by interactive bargaining model. This may imply that a majority of disputants in the university are integrative in nature and would therefore resort to agreements in resolving their conflicts.

4. Discussion

- The results show that the interests and needs of the majority of the disputants during conflict are mostly compatible, making successful conflict resolution possible. On the contrary, the positions disputants take are competitive, making the task of conflict resolution arduous. The results suggest that the distributive bargaining model (competing) is the most commonly used of the three conflict resolution models in the university. In terms of preference, disputants ranked the interactive problem solving model (collaborating) first. The integrative bargaining model (compromising) was ranked second and the distributive bargaining model was ranked third. These results suggest that disputants would prefer the interactive problem solving model used in conflict resolution in the university. The results tend to agitate towards open dialogue methods of conflict resolution which have been recommended by different researchers[7, 9-10, 12-13, 27].The model mostly used by disputants may influence their conflict resolution expectancies[13]. It thus appears that conflict resolution strategies that focus on the needs of the disputants are more favourable than those that do not. The results tend to concur with earlier studies that have established that conflict resolution approaches that increase optimistic expectancies and create perceptions of greater compatibility between the positions, interests, and needs of disputants may prove to be very useful for resolving many conflicts[9, 22, 27]. Similarly, negotiation approaches that increase pessimistic or belligerent expectancies among disputants and decrease the perceived compatibility between the interests and needs of conflicting groups could prove to be detrimental to the resolution of conflict.These results reveal that in conflict situations, disputants' attitudes toward the other and toward the conflict situation play an extremely important role in defining and creating the conflict situation, and may serve to facilitate the escalation or the resolution of the conflict. Thus an approach that moderates disputants’ attitudes as well as addressing their interests and needs is recommended to resolve intergroup conflicts within university setups. Such an approach has been recommended for institution based conflicts in earlier studies[9-10, 12-13, 27].

4.1. Limitations

- One limitation of this study involves the use of college students as participants. Such participants may have neither the knowledge base nor vested interests of real-life disputants. Thus, it may be inappropriate to use these results to describe or predict the behavior of disputants. Further, this study does not specify the nature of conflicts, and that the results may not be generalizable to all kinds of conflict.

5. Conclusions

- Future evaluation research should assess a broader range of dependent measures, so that we may identify the potential strengths and weaknesses of other conflict resolution models. Future research may also test the effect of sequencing different models to determine the most effective combinations of strategies for resolving different kinds of conflict. Since conflict itself has both positive and negative outcomes[29], the outcomes of the increasedstudents-administrators conflicts in educational institutions should continuously be evaluated through research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML