-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2013; 3(3): 168-177

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20130303.05

CLIL: A Science Lesson with Breakthrough Level Young EFL Learners

Zehra Gabillon1, Rodica Ailincai2

1Université de la Polynésie Française, BP 6570, 98702 Faa'a, Tahiti (EA Sociétés Traditionnelles et Contemporaines en Océanie)

2IUFM Université de la Polynésie Française, BP 6570, 98702 Faa'a, Tahiti (EA Sociétés Traditionnelles et Contemporaines en Océanie)

Correspondence to: Zehra Gabillon, Université de la Polynésie Française, BP 6570, 98702 Faa'a, Tahiti (EA Sociétés Traditionnelles et Contemporaines en Océanie).

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper reports on the implementation of a Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach to teach a science subject topic to young learners. The participants of the study were 10-11 year-old elementary school children who lived in Tahiti, French Polynesia. The study comprised four identical lessons: a) two CLIL lessons (English/L2); and b) two science subject lessons (French/L2). The approach used in the lessons drew on the principles of CLIL and sociocultural theories. The study was designed to investigate if CLIL could be applied effectively with beginner level young learners with 25- to 30-minute English as a Foreign Language (EFL) showers. The study also sought to explore if there would be any observable differences between a CLIL lesson (L2) and a subject lesson (L1) regarding: a) the teaching/learning of content knowledge; b) the learners’ willingness to participate in classroom activities; and c) the types of classroom interactions used. The study employed video recordings to gather data. The videotaped data were transcribed and the transcribed data were analyzed qualitatively by focusing on classroom exchanges, and non-verbal contextual elements. The data were also analyzed qualitatively by using descriptive statistics, and the results obtained were presented through histograms. The results indicated that successful CLIL practice is possible with Breakthrough level young learners. This study also showed that dialogic exchanges can be used both as a means for scaffolding content and language learning.

Keywords: CLIL, Language Learning, Sociocultural Theory, EFL, Scaffolding, ZPD, Classroom-Research

Cite this paper: Zehra Gabillon, Rodica Ailincai, CLIL: A Science Lesson with Breakthrough Level Young EFL Learners, Education, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 168-177. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20130303.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Content and Language Integrated Learning (henceforth CLIL) CLIL is a generic term used to describe an educational approach that uses a foreign, regional or a minority language or another official state language through which a school subject is taught. CLIL practices aim not only to improve language skills but also to enhance academic cognitive processes and intercultural understanding. The present paper reports on the preliminary data obtained in a classroom-based CLIL study conducted with a group of elementary school children in Tahiti, French Polynesia. The study was carried out by two researchers who are the members of the research team EASTCO at the University of French Polynesia. French Polynesia is an ‘Overseas Territory’ of France (COM-- collectivités d'outre-mer) and education is under the responsibility of both local authorities and French government. The foreign language teaching schemes in French Polynesian primary education are the extension of the early childhood foreign language education provision in France.In our study, we used CLIL as an approach to teach both a science lesson topic and English as a Foreign Language (hereafter EFL) skills to a group of Beginner level (Breakthrough level[1]) primary school children. In French Polynesian primary schools, EFL was first introduced in 2006 as a pilot project, and progressively extended to all French Polynesian primary schools. In effect from August 2011, EFL has become integral part of every primary school timetable ranging between 40 to 60 minute lessons per week and teachers are encouraged to integrate CLIL practice into their teaching schedule. The study used four 25-30 minute identical science lessons in the learners’ mother tongue (French/L1) and in the target foreign language (English/L2) to explore if there would be any observable differences between a CLIL lesson (in L2) and a regular subject lesson (in L1). There is substantial empirical evidence to support benefits and effectiveness of high exposure CLIL practices (about 40-50 % of the curriculum)[2],[3],[4]. However, the time allocated for CLIL in most European countries does not exceed 10% of the total teaching time on school curriculums[5], and so far, there has not sufficient evidence-based support on the effectiveness of CLIL practices as short irregular language showers with young learners. Thus, in our study we also attempted to discover if CLIL could be applied effectively with Breakthrough level young learners with 25- to 30-minute irregular EFL showers to teach content knowledge.

2. Literature Review

2.1. What is CLIL?

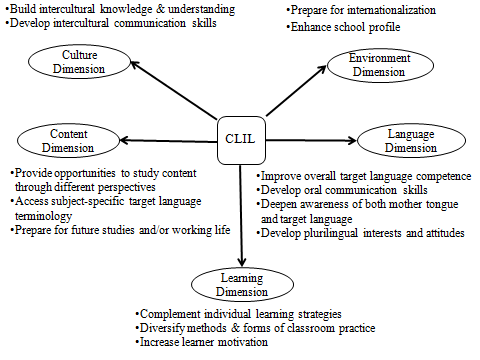

- CLIL has a dual educational focus with the objective of developing both language skills and disciplinary content knowledge[6]. Teaching school subject content through the medium of a foreign/second language has been in practice since the late 1960s in bilingual educational contexts. The immersion education programs (also known as French immersion), which have been in practice in Canada for almost half a century, represent the best example for such bilingual education programs. In English Language Teaching (henceforth ELT) milieus, the terms ‘Content-Based Instruction’ (CBI) and ‘bilingual education’ have also been used to refer to practices that support learning of foreign languages through disciplinary content learning.The term CLIL was first used in European educational settings with the bilingual/multilingual education provision prompted by the European Commission[7]. Although bilingual education practices had long existed in Europe, the term CLIL was not known until the early 1990s. The 1990s was the period, when multilingualism and language education became the key issue to improve communication among European Union (EU) citizens, and consequently economic activity across Europe[1]. The European Commission maintained that successful coexistence among peoples depended on enhancing cooperation and only citizens with language and cross-cultural communication skills could establish successful cooperation[7].This new situation called for a need for more exposure to foreign language learning. However, adding extra foreign language teaching hours on existing curricula did not prove possible. Thus, integrating foreign language learning with school subject learning was regarded as an ideal answer[7]. The effectiveness of content teaching through a medium of a second language was empirically supported by consistent research findings in Canadian context[8]. The results obtained from these studies suggested that bilingualism could positively affect children’s intellectual and linguistic development[9] (Cummins and Swain, 1986). CBI practices were also supported by Second Language Acquisition (SLA) and Foreign Language Learning (FLL) research[10],[11],[12]. These positive results concerning effectiveness of bilingual education practices supported the idea of integrating content and language learning. Thus, CLIL approach was proposed and accepted as a solution to provide learners with more exposure to foreign language learning[7]. Today CLIL is a priority concern of the European Commission, and many European countries implement CLIL as part of their mainstream educational programs. For the last decade, CLIL practices have gained impetus in Europe and interest for CLIL has gradually stretched across the other continents. Although CLIL as an approach, is gaining popularity and spreading throughout the world, it has not yet attained a fully developed educational model. CLIL practices in Europe show differences depending on the local conditions and requirements[3],[5]. Research done in this area is still scarce and classroom practices lack coherent application. The label CLIL is used to describe all types of practices that use a foreign language to teach school subjects regardless of the variations in conceptual frameworks, theoretical underpinnings and actual classroom practices[5], [13]. Although regular CLIL practices, which provide some amount of exposure, have suggested benefits both in foreign language and content learning[2],[3],[4], so far there has not yet enough evidence-based support on the effectiveness of short irregular CLIL practices with young Breakthrough learners[13].CLIL approach is based on five dimensions: learning, language, content, culture and environment (see Figure 1)[14]. It is maintained that teaching school subject content by using the target foreign language increases the amount of exposure the learner gets in the foreign language and provides the learner with richer L2 input.

| Figure 1. Dimensions of CLIL |

2.2. Which Theoretical Framework for CLIL?

- Growing body of educational and L2 research has been informed by sociocultural theories[16]. Many of these sociocultural theories have been influenced by Vygotsky’s[17] ideas. Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory has complemented learning theories such as Bandura’s social learning theory[18]; Lave’s situated learning theory[19]; and Bruner’s constructivist theory[20]. Vygotsky[17] viewed cognitive development as a social construction, which is developed with social collaboration. He claimed that optimal cognitive development depends upon the ‘zone of proximal development’ (ZPD) where individuals construct the new language through socially mediated interaction. Vygotsky put forth that engaging in full social interaction with others (peers, parents etc) enables ZPD to develop fully. He stipulated that the skills which the individual acquires through interaction with peers (with parents, and significant others, such as teachers, friends etc.) exceed what the individual can attain alone. According to this view, the degree of difference between autonomously acquired knowledge and knowledge that is acquired in collaboration constitutes the ZPD[21]. Lev Vygotsky’s social constructivist theory bears similarities with Piaget’s cognitive development theory. However, Vygotsky[17], differently from Piaget, conceptualized social interaction as the necessary source and condition for optimal cognitive development. Vygotsky’s view does not separate individual processes of knowledge construction from social processes and considers them as connected and interdependent. L2 learning/acquisition from this perspective holds that language learning and social interaction are in mutually dependent roles and that language learning cannot be understood devoid of the context in which it occurs[22]. Bruner[20] maintained that the child needs to be provided with appropriate social interactional frameworks for gaining and using knowledge. According to this view, language development occurs as the result of meaningful dialogic interaction. Sociocultural theories mainly focus on processes and changes rather than products and stages[17]. This approach does not view language process as a linear development. It holds that language learners go forth and back during the course of their interlanguage construction. Within this sociocultural perspective, activity theory (as an extension of Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory) also forms a coherent framework for theorizing L2 learning/acquisition [23]. In activity theory, the task constitutes the basic component of activity. According to activity theory, human development is conceptualized as a continuing attempt to solve various tasks. To achieve these tasks the language learner is provided with instructional scaffolding by a more skilled language user (teacher) who models the task. As the learner gains competence, the scaffolding is gradually lessened[24]. L2 research from a sociocultural perspective has been both supportive and demonstrative of the efficacy of Vygotsky’s ideas in obtaining desired L2 learning outcomes. Comparative research studies on the level of expert-novice mediated activity (L2 teacher-L2 learners), and peer-mediated activity (L2 learner-L2 learner) have demonstrated positive results in favor of mediated activity in second/foreign language classrooms[23]. Second language research has also demonstrated that many of the language forms that young children played with in their private speech (self-talk) appeared later when they engaged in L2 activities[23]. According to Vygotsky, knowledge is first co-constructed at social planes through interactions with others and then this knowledge is appropriated (internalized) at personal planes[17]. Sociocultural theories hold that individuals discover how new knowledge connects with prior knowledge through active personal experience. From sociocultural perspectives, knowledge construction is a social, contextualized process and via this process learners test hypotheses through social negotiation and each individual has a different interpretation of this social experience.Sociocultural paradigms view learning as an active, situated, constructive process where learners collaboratively construct new information and link this new information to previously acquired knowledge[19]. Sociocultural theories maintain that when learners link new knowledge to a prior experience they understand and retain new concepts better. Classroom activities that emphasize learner involvement such as hands-on activities, including lab work, experimentation, and simulations are considered typical activities in a sociocultural classroom[25].

3. Aim of the Study

- The study describes a classroom-based research on the implementation of a CLIL approach. The part we describe in this paper constitutes the first two phases of a longitudinal explorative CLIL research (four videoed lessons). The study sought to understand if there would be any observable differences between a science lesson taught in the children’s mother tongue (French), and the target language (English) concerning: a) the teaching/learning of the disciplinary content; b) the learners’ willingness to participate in the activities; c) the types and functions of the classroom interaction patterns used during the activities. The study also sought to explore if CLIL could be applied effectively with Breakthrough level young learners through irregular EFL showers. It should be noted that we did the same lessons both in French and English for research purposes only. We are conscious that the key objective of CLIL is not to add extra foreign language teaching hours on the school curriculum but to use the existing hours on the curriculum to create more L2 opportunities.

4. CLIL: Principles and Planning

- The aim of this CLIL practice was dual: to provide the children with language practice and to teach new science content. The lessons were designed building on Vygotsky’s ideas. The lessons intended to allow both a hands-on experience and dialogical exchanges to scaffold learning (both in L2 and content knowledge). When we planned our study, we considered both the principles of CLIL and SCT and we based our CLIL study on the following principles: ● enable the learners to learn a school subject on their curriculum using the L2 they are learning at school;● select the school subject content taking into account their ability in the L2; ● provide instructional scaffolding to support learning of both the L2 and the disciplinary content;● support the use of learner strategies and cognitive skills; ● provide the learners with experiential learning and hands-on experience to help them learn by doing; ● provide learners with authentic learning settings[e.g. doing a science experiment using lab equipments and everyday substances];● enable the learners to learn skills that they can transfer and use in other similar contexts (e.g. know-how skills to complete tasks and solve problems which involve cognitive skills) and practical skills (e.g. employment of manual skills and methods, materials, tools and instruments).

5. Context and Participants

- The study took place in a primary school in Tahiti, French Polynesia. The participants of the study were 16 primary school pupils between the ages of 10-11 who lived in Tahiti, French Polynesia. The participants were nine girls and seven boys. They all spoke French as their first language and they all had had approximately a year of EFL experience. The learners had Breakthrough EFL level, and could use basic language structures and phrases. This classroom-based research was carried out in collaboration with three educational professionals: a generalist teacher who was also the class teacher, a researcher in education, and a researcher specialized in teacher training and EFL research. The class teacher provided the researchers with the essential information concerning the science subject topics on the curriculum, and helped with the selection of the theme. The EFL specialist had been teaching this group of children since the beginning of the 2011-2012 academic-year and she knew the pupils well. Both the class teacher and the EFL teacher worked together and prepared the lesson plans. The class teacher taught the lesson in French and the EFL teacher taught the same lesson in English.

6. Procedure

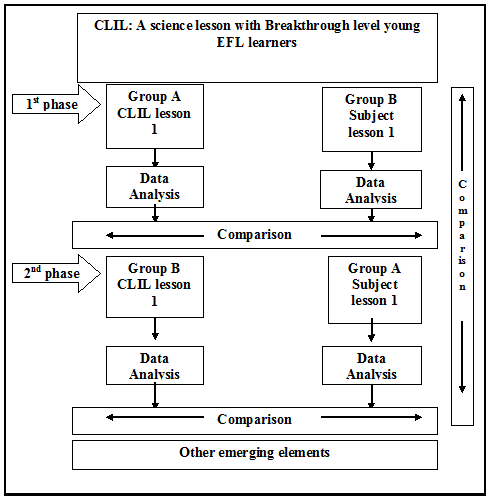

- The science lesson required the pupils to do an experiment to see if the given substances were soluble or insoluble in water and give a description of the liquid they had obtained. This science subject topic was on the curriculum but the pupils had not done an experiment of solubility in their science classes before. The class (n 16) was divided into two groups Group A (n=8), and Group B (n8) and each group received the same lesson both in English and in French (See Figure 2). The study comprised two phases. In Phase 1, Group A received the lesson in English and Group B in French. In Phase 2 the teachers swapped the groups, and did the same science experiment this second time in French with Group A and in English with Group B. Each lesson took between 24 to 27 minutes.

| Figure 2. The phases of the classroom-based CLIL study |

7. Instruments

- We used video recordings to gather data, and prior to the research, the parents signed a consent form giving permission for videoing their children. The videotaped data were transcribed and the transcribed data were analyzed by focusing on: a) classroom exchanges and b) other non-verbal contextual elements. We also analyzed the data by using descriptive statistics. We used grids on which we tallied occurrences of the classroom exchanges and the interaction patterns used during the lessons. We observed the children’s behavior during the activities, such as their involvement, interests towards the activities, attention, group dynamics and so forth. Using video recordings as means to collect data allowed us to have more flexibility than we could have with a real-time classroom observation. This method helped us to do retrospective analysis to re-examine the data as much as required. The videotaped material also enabled us to identify and analyze not only the linguistic data but also non-verbal elements of the phenomena observed. Due to small group size, we were able to obtain uninterrupted view of every single student in the video recordings. Having uninterrupted view of the entire group enabled us to view how each learner experienced the learning instances at each stage of the lesson, and how differently each individual learner reacted at the same circumstances.

8. Analysis

- In Phase 1 we sorted and analyzed the data obtained from Group A (CLIL lesson/L2) and Group B (subject lesson/L1) then compared the data obtained from each group with each other. We repeated the same procedures in Phase 2 and then compared the data obtained in Phase 2 with the data obtained in Phase 1. In Phase 2, the groups were taught the same subject content by swapping the language of instruction (Group A in French and Group B in English)

8.1. Phase 1/CLIL Lesson /Group A

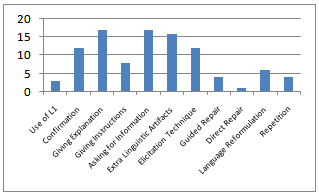

- In Phase 1, the first lesson was in English with Group A. We sought to investigate if it was possible to teach a science lesson successfully to a Breakthrough level young EFL learners using 25-to 30-minute irregular CLIL lessons.The first CLIL lesson took 27 minutes and comprised of 123 turn-takings (T-Ls 27%, L-T 28%, T-L 21%, Ls-T 15%, and Ls-Ls 5%, Self-Talk 4%). The lesson was designed to emphasize teacher-learner exchanges and teacher scaffolding because of the learners’ English level. Most of the exchanges that took place during the lesson were in the form of teacher

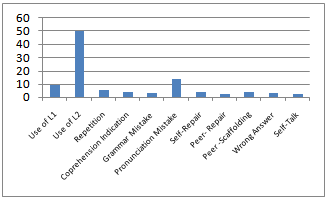

learner and learner

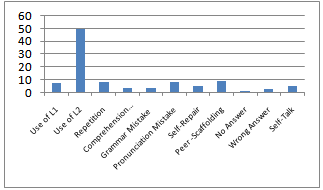

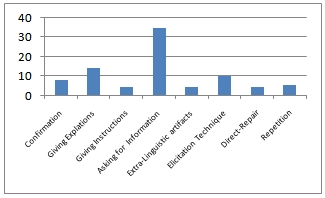

learner and learner  teacher interactions.The learners’ low level of English required the teacher to scaffold learning with care, using short exchanges. In the first CLIL lesson most of the teacher talk was in the form of short phrases/questions and was aided with extra-linguistic artifacts (demonstrations, use of realia, gestures etc.) (see Figure 3). It should be noted that, most of the time, in an exchange the teacher used more than one scaffolding strategies. Thus, the frequency of the strategies used by the teacher should not be interpreted as the frequency of the teacher talk.

teacher interactions.The learners’ low level of English required the teacher to scaffold learning with care, using short exchanges. In the first CLIL lesson most of the teacher talk was in the form of short phrases/questions and was aided with extra-linguistic artifacts (demonstrations, use of realia, gestures etc.) (see Figure 3). It should be noted that, most of the time, in an exchange the teacher used more than one scaffolding strategies. Thus, the frequency of the strategies used by the teacher should not be interpreted as the frequency of the teacher talk.  | Figure 3. CLIL lesson 1: Frequency of teacher scaffolding strategies |

| Figure 4. CLIL lesson 1: Types and frequency of learner interactions |

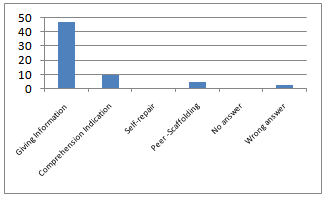

Learner exchanges mainly took place in L1 except a few which were in the form of half French half English (e.g. Il est ‘clear’ /klɪər /; C’est ne pas ‘cloudy’/ˈklaʊ.di/ etc.). These learner exchanges were all about the lesson and they were mainly in the form of peer- scaffolding (see examples in L1 in Extract 1). The dialogic exchanges between the teacher and learners helped the learners to acquire new concepts and words, to use the target language in a natural setting, and to self-repair their errors. The setting also enabled the use of extra-linguistic artifacts (e.g. lab tools, substances, etc.) (see Extract 1 and Extract 2). Extract 1T: Look! Can you see the sugar? (Points the bottom of the jar).Ps: Yes—(some) Yes, I do.T: Now I ... (children do not know the word ‘stir’) … stir it (The teacher demonstrates it). Stir it...stir it...stir it… (Teacher’s repetition of the word ‘stir’ makes children laugh). Where’s the sugar? Can you see it?Ps: No.T: It is ... Sugar is... Ps: Soluble (some of them pronounce it as /sɒljʊbəl/ and some as /sɔlybl/).T: In...Ps: Water.T: Excellent.! Sugar is soluble /sɒljʊbəl/ in water.[The children start whispering to each other in French.]P2: On le voit plus parce qu’il est soluble dans l’eau (We connot see it because it is soluble in water). P3 Mais, il est là en fait. Même s’il est soluble. Il est mélangé avec l’eau (But, it is there in fact. Even if we do not see it. It is mixed with water).Extract 2T: Let us test another substance (the teacher models the activity). (She puts some sand in water) we stir it...stir it...stir it again...and... Ps: Insoluble (several pupils at the same time)T: Why?Ps: (No answer).T: Look at the bottom of the jar (she holds the jar up, and points the bottom of the jar with a spoon). P2: I see sand.T: Yes, it doesn’t mix with water. It falls to the bottom of the jar. Can you see it? Here... (Shows it).(T: Teacher, P1: Pupil 1, Ps: Pupils)Most of the English terms used in the experiment were similar to their French equivalents (e.g. soluble, insoluble, liquid etc.) and this seemed to have contributed to the learners’ understanding of the new concepts but the differences in pronunciation created some confusion. The learners had the tendency to insist on the French pronunciation. The teacher used guided-repair techniques such as repeating the answer with the correct pronunciation and/or asking another question that required the learner to repeat the correct pronunciation (see Extract 3). Extract 3S7: Flour and water. Flour and water…soluble /sɔlybl/... (She hesitates).T: Is flour soluble /sɒljʊbəl/ … ?S7: Flour is soluble /sɒlubel/ ... soluble /sɒljubel/ in water.T: Is flour soluble /sɒljʊbəl/ in water? Look at the bottom of the jar.S7: No, No...flour is insoluble /ənsɔlybl/ in water.The dialogic exchanges also demonstrated that the learners were able to articulate their understanding of the topic by using both L1 and L2, and other means such as artifacts, and gestures (see Extract 4). Extract 4[P5 could not decide whether soap was soluble or insoluble in water because pieces of soap were floating on the surface of the water]T: Ok. Do the experiment again (passes the jar to P5). Take some soap (some finely grated soap this time). Put it in water. Stir it…, stir it very well. (P5 stirs energetically) Oh!! We can see bubbles (Children laugh). What do you think? Is soap soluble or insoluble?P5: Soluble T: Why?P5: I can’t see the soap (shows the bottom of the jar). I can’t see the soap (shows the surface of the water)The feedback given by the learners at the end of the experiment indicated that they were able to differentiate between soluble and insoluble substances, able to give simple descriptions, and explain why some substances were soluble/insoluble by using simple English (see Extract 5).Extract 5P1: Sand is insoluble in water and the liquid is clear, transparent.P2: Rice is insoluble in the water ... the liquid /likid/ is hmm white and cloudy?S4: Salt. Salt is soluble and the water is clear.S6: Coffee. Coffee is soluble /sɒlubel/ (instant coffee) in water and the liquid /likid/ is brown. The learners used simple language forms (in general correctly) however, there were minor problems concerning the grammar (e.g. articles, word order etc.) and pronunciation (problems concerning L2 learning were not dealt with in this lesson). In our study, we did not use formal assessment procedures but merely analyzed dialogic exchanges for indication of increased understanding (knowledge-gaining). During this first CLIL lesson, we observed that the learners were able to gain knowledge through dialogic exchanges. The science topic and the experiment we selected did not require complex language structures and the CLIL teacher used short and simple dialogic exchanges, gestures, realia and modeling to scaffold understanding and concept building. This experiment provided a necessary framework for efficient instructional scaffolding in a natural setting. The natural setting, created by the experiment, enabled integration of both the content and L2 providing the learners with a variety of sensory input (seeing, touching, smelling etc.). In brief, this first lesson suggested that successful CLIL is possible with Breakthrough level learners.

Learner exchanges mainly took place in L1 except a few which were in the form of half French half English (e.g. Il est ‘clear’ /klɪər /; C’est ne pas ‘cloudy’/ˈklaʊ.di/ etc.). These learner exchanges were all about the lesson and they were mainly in the form of peer- scaffolding (see examples in L1 in Extract 1). The dialogic exchanges between the teacher and learners helped the learners to acquire new concepts and words, to use the target language in a natural setting, and to self-repair their errors. The setting also enabled the use of extra-linguistic artifacts (e.g. lab tools, substances, etc.) (see Extract 1 and Extract 2). Extract 1T: Look! Can you see the sugar? (Points the bottom of the jar).Ps: Yes—(some) Yes, I do.T: Now I ... (children do not know the word ‘stir’) … stir it (The teacher demonstrates it). Stir it...stir it...stir it… (Teacher’s repetition of the word ‘stir’ makes children laugh). Where’s the sugar? Can you see it?Ps: No.T: It is ... Sugar is... Ps: Soluble (some of them pronounce it as /sɒljʊbəl/ and some as /sɔlybl/).T: In...Ps: Water.T: Excellent.! Sugar is soluble /sɒljʊbəl/ in water.[The children start whispering to each other in French.]P2: On le voit plus parce qu’il est soluble dans l’eau (We connot see it because it is soluble in water). P3 Mais, il est là en fait. Même s’il est soluble. Il est mélangé avec l’eau (But, it is there in fact. Even if we do not see it. It is mixed with water).Extract 2T: Let us test another substance (the teacher models the activity). (She puts some sand in water) we stir it...stir it...stir it again...and... Ps: Insoluble (several pupils at the same time)T: Why?Ps: (No answer).T: Look at the bottom of the jar (she holds the jar up, and points the bottom of the jar with a spoon). P2: I see sand.T: Yes, it doesn’t mix with water. It falls to the bottom of the jar. Can you see it? Here... (Shows it).(T: Teacher, P1: Pupil 1, Ps: Pupils)Most of the English terms used in the experiment were similar to their French equivalents (e.g. soluble, insoluble, liquid etc.) and this seemed to have contributed to the learners’ understanding of the new concepts but the differences in pronunciation created some confusion. The learners had the tendency to insist on the French pronunciation. The teacher used guided-repair techniques such as repeating the answer with the correct pronunciation and/or asking another question that required the learner to repeat the correct pronunciation (see Extract 3). Extract 3S7: Flour and water. Flour and water…soluble /sɔlybl/... (She hesitates).T: Is flour soluble /sɒljʊbəl/ … ?S7: Flour is soluble /sɒlubel/ ... soluble /sɒljubel/ in water.T: Is flour soluble /sɒljʊbəl/ in water? Look at the bottom of the jar.S7: No, No...flour is insoluble /ənsɔlybl/ in water.The dialogic exchanges also demonstrated that the learners were able to articulate their understanding of the topic by using both L1 and L2, and other means such as artifacts, and gestures (see Extract 4). Extract 4[P5 could not decide whether soap was soluble or insoluble in water because pieces of soap were floating on the surface of the water]T: Ok. Do the experiment again (passes the jar to P5). Take some soap (some finely grated soap this time). Put it in water. Stir it…, stir it very well. (P5 stirs energetically) Oh!! We can see bubbles (Children laugh). What do you think? Is soap soluble or insoluble?P5: Soluble T: Why?P5: I can’t see the soap (shows the bottom of the jar). I can’t see the soap (shows the surface of the water)The feedback given by the learners at the end of the experiment indicated that they were able to differentiate between soluble and insoluble substances, able to give simple descriptions, and explain why some substances were soluble/insoluble by using simple English (see Extract 5).Extract 5P1: Sand is insoluble in water and the liquid is clear, transparent.P2: Rice is insoluble in the water ... the liquid /likid/ is hmm white and cloudy?S4: Salt. Salt is soluble and the water is clear.S6: Coffee. Coffee is soluble /sɒlubel/ (instant coffee) in water and the liquid /likid/ is brown. The learners used simple language forms (in general correctly) however, there were minor problems concerning the grammar (e.g. articles, word order etc.) and pronunciation (problems concerning L2 learning were not dealt with in this lesson). In our study, we did not use formal assessment procedures but merely analyzed dialogic exchanges for indication of increased understanding (knowledge-gaining). During this first CLIL lesson, we observed that the learners were able to gain knowledge through dialogic exchanges. The science topic and the experiment we selected did not require complex language structures and the CLIL teacher used short and simple dialogic exchanges, gestures, realia and modeling to scaffold understanding and concept building. This experiment provided a necessary framework for efficient instructional scaffolding in a natural setting. The natural setting, created by the experiment, enabled integration of both the content and L2 providing the learners with a variety of sensory input (seeing, touching, smelling etc.). In brief, this first lesson suggested that successful CLIL is possible with Breakthrough level learners.8.2. Phase 1/Subject Lesson /Group B

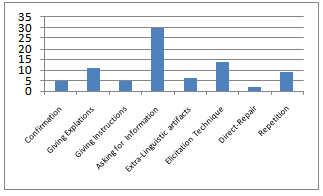

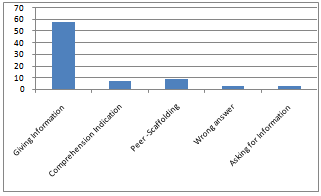

- Group B received their first lesson in French. The class teacher followed more or less the same procedures as the CLIL teacher. There were 118 turn-takings and the lesson took 25 minutes. In this lesson teacher had recourse to extra- linguistic artifacts less than the CLIL teacher did. Due to the native language use, the classroom interactions were richer. Although the teacher had recourse to various instructional scaffolding methods such as using realia, identifying objects by touching, seeing, smelling and so forth, she used primarily dialogic exchanges to scaffold learning. To assist learners in their knowledge building, the teacher asked for language precisions and helped the learners relate new knowledge to their prior knowledge (see Figure 5 and Extract 7).

| Figure 5. Subject lesson 1: Frequency of teacher scaffolding strategies |

| Figure 6. Subject lesson 1: Types and frequency of learner interactions |

8.3. Phase 2/CLIL Lesson /Group B

- Group B had the experiment in CLIL a week after they had the same lesson in French. The lesson comprised 119 turn-takings and took 25 minutes. The classroom interaction patterns used in this lesson were similar to the previous two lessons. The learners already knew what type of experiment they were going to do but they still seemed interested and willing to participate[this group was slightly more dynamic than Group A in their subject lesson, as well (see section 8.2)]. The analysis of classroom interactions showed that in this CLIL lesson the teacher gave fewer explanations and had recourse to extra-linguistic artifacts less. Instead, the teacher demanded more explanations and clarifications from the learners themselves (see Figure 7).

| Figure 7. CLIL lesson 2: Frequency of teacher scaffolding strategies |

| Figure 8. CLIL lesson 2: Types and frequency of learner interactions |

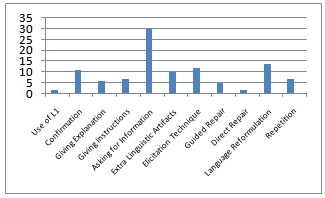

8.4. Phase 2/Subject Lesson /Group A

| Figure 9. Subject lesson 2: Frequency of teacher scaffolding strategies |

| Figure 10. Subject lesson 2: Types and frequency of learner interactions |

8.5. Overall

- The overall results obtained from this classroom-research can be summarized as follows:1) We observed that CLIL is possible with beginner level young learners. The lessons made use of extra-linguistics artifacts to complement the L2 and help the learners understand new concepts. During the CLIL lessons, the teacher tried to make the L2 input comprehensible by means of input simplification and through the use of linguistic and extra-linguistic context. The data obtained from this experience suggested that CLIL with young beginner level learners require a rich extra-linguistic context and socially mediated activity designs. Our experience also suggested that with beginner level CLIL learners the activities need to evolve gradually from teacher-learner mediated activity to peer-mediated activity patterns. 2) The subject teacher, used the extra-linguistic context less compared to the CLIL teacher, and she had recourse to the learners’ mother tongue as the primary means for scaffolding. The major teacher scaffolding technique consisted of demanding language precisions and employing elicitation techniques.2) The analysis of the learners’ responses demonstrated that the objectives of all four lessons were attained concerning the targeted disciplinary content learning. 3) In the CLIL lessons, the children used the L2 more than 90% of the total classroom interactions. They responded the teacher willingly and were able to cope with all the task requirements without any observable difficulty. 4) In our lessons dialogic exchanges mainly took place between teacher and learners and these exchanges were used to scaffold learning (L2 or/and content learning).5) Overall, we did not notice any significant observable differences in the learners’ classroom behaviors except that the learners seemed more confident during the subject lessons, in which they used their mother tongue. On the whole, the learners showed willingness to participate in all four lessons.

9. Conclusions

- The results of this study were based on the data gathered at the preliminary stage of a longitudinal classroom-based research. At this stage, our research has only observed a small group of language learners and the data we obtained cannot be generalized. However, our research is noteworthy regarding the framework it provides for CLIL practices with beginner level young learners. Our study indicated that successful CLIL practice is possible even with Breakthrough level young learners. This study also showed that dialogic exchanges can be used both as a means for scaffolding and language learning. Our study had some limitations. We gathered data merely by using video recordings. At this preliminary stage, we did not use post-teaching assessment procedures to measure the learning of the content knowledge or the English language, but relied solely on observation and the feedback obtained at the end of the lessons. CLIL practices have been integrated to school curricula across Europe only recently and such practices are still new to many teachers[5]. Thus, CLIL practitioners and researchers need more classroom-based examples to compare and gain insights about actual classroom practices. CLIL practices represent innovation to learners, as well as teachers; therefore, supplementing research data with learner and teacher interviews and obtaining both the learners and the teachers’ opinions on their CLIL experiences would provide richer data and widen perspectives. There is also a need for further research to focus on differences between maximal versus minimal CLIL exposure settings. Such research should try to identify differences in: a) CLIL outcomes in maximum versus minimum exposure settings; b) teaching approaches and theoretical frameworks used; and c) learner motivations in different CLIL settings. The CLIL practice described in this paper based its approach on a sociocultural framework. There is empirical evidence on successful application of sociocultural theories in SLA settings[16][23], and in diverse educational contexts [26]. We believe that a sociocultural framework would provide the theoretical foundation that could constitute a reference point to CLIL practitioners. At present, CLIL provision does not provide teachers with clear teaching guidelines and appropriate teaching resources[5][13]. This issue, as well as teacher training, should be the key concern for promoting better CLIL instruction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to thank Jacqueline Ferlicoq for her invaluable help and participation in our research. We would also like to convey thanks to Patricia Teriiteraahaumea, the head teacher at the primary school ‘2+2=4’ in Tahiti, for providing us with support and facilities.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML