-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2013; 3(1): 91-97

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20130301.12

Examining Student Character Development Within the Liberal Arts

Michael D. Thompson 1, Irving I. Epstein 2

1Office of Institutional Research & Planning, Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL, USA

2Department of Educational Studies, Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL, USA

Correspondence to: Michael D. Thompson , Office of Institutional Research & Planning, Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study examines issues involving student character development within the small liberal arts institutional setting. It uses one highly selective liberal arts institution as a case study and analyzes the effects of its attributed contributions from various institutional resources within the context of Astin’s[1] input-environment-outcome (I-E-O) model. Data elements from 356 student participants in their fourth undergraduate year were utilized and were extracted from merged longitudinal databases that included matching student responses from the 2004 and 2007 Student Information Forms (SIF) and the 2008 and 2011 College Senior Surveys (CSS). Although the results of the study confirm many conventional understandings regarding student character development, they also raise larger questions regarding the role and effectiveness of small liberal arts institutional environments as well as their larger counterparts, in contributing to its enhancement.

Keywords: College Students, Character Development, Liberal Arts

Cite this paper: Michael D. Thompson , Irving I. Epstein , Examining Student Character Development Within the Liberal Arts, Education, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2013, pp. 91-97. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20130301.12.

Article Outline

1. Introduction and Literature Review

- Student character development as a college experience outcome has been an essential aspect of higher education for centuries. Historically, many character development attributes derived from religious doctrines and the mission statements of religiously affiliated institutions that emphasized values congruent with their respective denominational beliefs. Among others, these emphasized values often included an understanding of social and cultural norms, a consideration for others, spiritual sincerity, and a personal code of moral and ethical principles [12][20][23][32]. While some higher education historians traditionally have argued that the liberal arts college became an out molded organizational form by the mid-19th century, necessarily superseded by the growth of the research oriented alternative due to its size, inefficiency, and overt sectarianism[24], others point to its survival as having occurred because of the forms of community and external support it was able to muster in spite of funding challenges, due to its denominational associations and ethical concerns [28]. Formal recognition of the enduring importance of the aforementioned values to contemporary liberal arts institutions may be observed in their mission statements. Numerous well-respected liberal arts institutions emphatically state that character development remains asignificant institutional objective and an over-riding rationale for their existence[6][8][10][15][17][31]. What does seem to be clear is that in spite of its strong historical roots in higher education, the importance placed on student character development has somewhat diminished over time because many institutions became more secularized in their operations as a response to a changing demographic with different goals and needs. Trends have emerged over the past 20 years revealing decreases in the emphasis faculty and students place on the development of various character attributes, altruistic interests and civic engagement as part of the undergraduate experience. This evidence, as well as the continued transgressions in corporate and political arenas, has caught the attention of many higher education scholars. One of the reactions to such concern has been a renewed interest in character development as a significant aspect of the undergraduate experience, a focus deemed even more important given the presence of these countervailing pressures that ignore traditional institutional legacies and priorities[1][5][7][9][20][22][23][26].In recent years, a number of studies have examined which aspects of the undergraduate experience promote and enhance character development. The totality of the evidence suggests a number of contributing curricular and co-curricular related areas. For example, the association between students who observe religious traditions and/or attend religious services with evidence of their enhanced character development is a longstanding one, repeatedly documented within the higher education literature[27][21]. In addition, the significance of peer interaction upon students’ socio-political values and attitudes has been widely acknowledged, as has its influence upon interpersonal competence[19][23]. Experiences with peers from different racial/ethnic groups, exposure to courses on cultural and ethnic differences, participating in community service, leadership training and internships, and formal and informal interactions with faculty all seem to have positive effects upon student character development[5][20][22][23]. However, within such a constellation of activities, a few, have received intensive comment. In commenting upon the effects of student-faculty interactions, for example, Jenney [16] found that faculty mentoring of students demonstrated positive effects upon pro-social student character development, although those effects were greater for those activities that can be categorized as achievement oriented than those that were social or compassionate self-concept oriented. To the extent that the mentoring process was influential in both domains, it was noted that advising and discussion activities among students and their professors that occurred outside of classroom were important.Gray and her associates[14], in examining service learning, found that its effects were generally significant but small with regard to tolerance attitudes. However, it has been noted that when such experiences are integrated with formal coursework, positive effects have been observed regarding increases in student achievement and teaching effectiveness[4][14][25]. As one might expect, community service experiences that are more closely tied to other forms of learning have greater salience with regard to character development as well as academic achievement, a contention borne out in the work of Pascarella & Terenzini[23]. They list a number of studies that indicate that service learning experiences have a greater net effect than do volunteer experiences on students’ tolerance levels, ability to see different perspectives, and international understanding. On the other hand, the degree to which such effects are long lasting once the undergraduate years have been completed also has been questioned[13]. Studies of students’ ability to engage in principled moral reasoning during their college years indicate that their capability in this area increases at least in part because of their undergraduate experiences such as the ones listed above, and that the articulation of principled moral reasoning resonates with similarly influenced behaviors[23].Additionally, research during the 1990s led some to conclude that the overall impact of small liberal arts institutions upon student altruism has continued to be significant in contemporary eras[2][18]. On the other hand, with specific regard to socio-political attitudes and values, Pascarella & Terenzini[23] note “differences in the structural characteristics of institutions are at best weak predictors of changes in students’ civic and community involvement or in their sense of responsibility for contributing to community improvement (p. 337).” Such a diversity of viewpoints with regard to the efficacy of the small liberal arts college experience speaks to the need to revisit the small liberal arts institution to determine if it really is a site that generically promotes student character development, and, what such conclusions might suggest for all higher education institutions with respect to their ability to encourage similar patterns of student attitudes and behaviors. In summary, undergraduate experiences do have an effect upon student development and character development in a global sense. However, much remains to be learned as to which experiences hold particular salience and why, along with what influences different institutional structures and the cultures they support and construct.The present study will contribute to the above research on student character development by examining one highly selective liberal arts institution and the effects of its attributed contributions from various institutional resources within the context of Astin’s[1] input-environment-outcome (I-E-O) model. Astin’s I-E-O model was selected for this study because of its proven usefulness in observing student learning and growth (outcomes) as a result of students’ entering characteristics (inputs) and their exposure to institutional resources (environment). The attributed contributions from various institutional resources to students’ character development will be examined, while controlling for students’ predisposition to character building activities and attributes. As noted in previous studies, engagement with institutional resources (e.g., co-curricular and coursework activities, interactions and experiences) has a significant influence on the differential patterns of student learning and growth[1][23] [29][30], thus making the use of the I-E-O model particularly salient for the present study.The main objective of the present study is to not only observe the impact of institutional resources previously noted as having significant effect on student character development, but to identify differences, if any, in the substance and strength ofthe contributing resources within a small liberal arts setting. Given the unique environment of the small liberal arts institution that emphasizes and markets itself on the close, personal attention and interactions amongst faculty, staff and students, one might expect that the results yielded from this examination would reflect positive evidence of these attributes.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

- This study was based on a sample of seniors at a private liberal arts institution located in the Midwest United States with an approximate enrollment of 2,050 students. Data elements from 356 student participants in their fourth undergraduate year were utilized for the present study. Two senior classes were included in the analysis, representing 46% and 37% of their respective senior classes. The male population was doubled via weighting procedures, which used the frequency variables (e.g., men = 2) as case weights. This procedure has been noted as an effective tool in eliminating the influence of differential response rates[11]. All subsequent analyses were based on a weighted number of 405 participants (females=58%; males=42%), who provided full information on all variables. Approximately 9% of the participants were students of color, 2% international and 89% white - a moderate overrepresentation of white students for the institution’s senior classes (84% and 78%).

2.2. Instruments

- The data elements utilized for the present study were extracted from merged longitudinal databases that included matching student responses from the 2004 and 2007 Student Information Forms (SIF) and the 2008 and 2011 College Senior Surveys (CSS). The SIFs were administered during the student orientation programs of the students’ first year, while the CSS instruments were administered in the final semester of the students’ senior year. All surveys were administered through the Higher Education Research Institute at the University of California - Los Angeles.

2.3. Variables

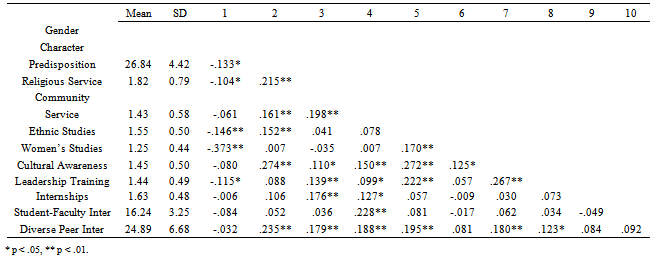

- The present study utilized a composite variable to represent character (dependent variable), which included 15 items related to students’ development, engagement and the importance they placed in areas concerning family, social justice, civic engagement, and religion. The selected items were taken from the CSS and were largely based on measures derived and validated through exploratory factor analyses in Astin and Antonio’s[5] study regarding the impact of college on character development. These measures examined character as a conglomeration of attitudes, beliefs, morals, values and behaviors highly favored in society. In addition, the measures are representative of the program goals utilized by the Templeton Foundation’s selection process in identifying institutions for their Honor Roll of Character Building Colleges. A summation of the character items yielded an alpha of .77, with a mean score of 43.6 (out of 62) and a standard deviation of 5.9.Identified from previous studies[5][20][22], nine resources (independent variables) based on students’ interactions, experiences and activities were identified in the CSS instruments. Student-faculty interaction was examined through a 7-item scale, while interaction with peers from a racial/ethnic group different from their own was assessed via a 9-item scale. The alphas for the scales were .86 and .87, respectively. Seven individual items accounted for attending ethnic and women’s studies courses and workshops, religious services, leadership training, internships, and community service. An 11-item composite variable (alpha = .63) was utilized to control for students’ pre-college engagement in activities and their predisposition concerning objectives related to character development (e.g., family, social justice, civic engagement, religion).

2.4. Research Design and Procedures

- Based on the aforementioned evidence concerning student character development, the following social, co-curricular and coursework related areas were included: experiences with peers from different racial/ethnic groups, exposure to courses on cultural and ethnic differences, participating in community service, leadership training and internships, attending religious services, and formal and informal interactions with faculty. Linear regression procedures were used to assess the contributions from various institutional resources to students’ character development, while controlling for students’ predisposition to character building activities and attributes, as well as gender. The design of the present study was guided by a set of expectations:● Students’ predisposition to character development (input) would affect developmental outcomes● Participation in religious services would affect students’ character development● Formal and informal interactions with faculty would have a strong effect on students’ character development● Interactions and experiences with peers from diverse races and ethnicities would have a strong effect on students’ character development● Co-curricular and coursework activities would affect students’ character development

|

|

3. Results

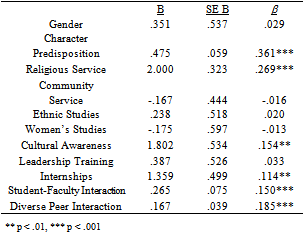

- Linear regression analysis was used to test if institutional resource engagement significantly predicted students’ character development. The results of the regression indicated that six of the 11 predictors explained 48% of the variance (R2 = .48, F (11, 312) = 26.14p < .001). It was found that student’s predisposition to character development (B = .475, p < .001), attending religious services (B = 2.000, p < .001), attending racial/cultural workshops (B = 1.802, p < .01), participating in internship programs (B = 1.359, p < .01), and interactions with faculty (B = .265, p < .001) and peers from a racial/ethnic group different from their own (B = .167, p < .001) significantly predicted student character development. Engagement with community service, ethnic and women’s studies courses, leadership training and gender yielded non-significant results.

4. Discussion

- At first glance, the results of the present study confirm many conventional understandings regarding student character development. The association between students who observe religious traditions and evidence of their enhanced character development is a longstanding one, repeatedly documented within the higher education literature [3][27][21]. It is therefore not surprising that in the present study, religious service attendance is the single greatest variable influencing enhanced character development. In a similar vein, one would also expect those who exhibit a predisposition to character development to show evidence of further development during their college years, and this indeed was the case in this sample. In addition to the religious attendance category, it is noteworthy that attending a cultural awareness workshop and participating in internships were categories that stand out as being particularly influential. Although certainly not equivalent to the full range of behaviors that constitute character development, these findings generally comport with Astin’s[1] conclusion that such experiences increased students’ political liberalism and social activism. Experiencing a strong degree of faculty and diverse peer interaction, while not as striking, still demonstrated significant influence in one’s character development.It is especially noteworthy that student interaction with diverse peers was a significant indication of character development, while taking an ethic studies course and enrolling in a women's studies course did not produce a significant outcome. As noted in Appendix A, the items comprising the “diverse peer interaction” category were wide-ranging. Among others, they included sharing a meal, studying, socializing, and having discussions concerning racial/ethnic tensions. It is thus clear that the results of many of these interactions might naturally serve as a more powerful influence upon character development than some of the factors involved with coursework exposure. In any case, the comparative value of curricular and co-curricular experiences in enhancing character development is an issue that deserves more intense investigation in future research.A second finding that is particularly interesting in the present study concerns the lack of influence of community service on character development. These findings raise larger questions involving the ways in which community service is defined and the conditions under which such engagement occurs. For example, if students pursue community service related projects because of their perceived importance for resume building or future professional advancement, the influence of the experiences may be less pronounced than anticipated. On the other hand, if community service involves the use of skills that are repetitive or lack intellectual challenge, one would expect that its influence would also be limited. Finally, it would be useful to examine the efficacy of programs that share community service and formal curricular expectations, rather than service engagements that stand-alone. As previously noted, a number of studies have shown that community service experiences that are more closely tied to other forms of learning have greater salience regarding character development, as well as academic achievement. Presumably, those students who profited most from community service would have been more likely to have viewed the purposes of such engagement with greater clarity and would have been able to better contextualize the importance of these experiences than those who did not. Nonetheless, it is clear that more studies analyzing the specific variables that constitute meaningful student community service and their limitations would be worthwhile.A somewhat surprising finding of the present study is the comparatively modest impact faculty interactions with students had upon students' character development. Similar to the “diverse peer interaction” category, the items included in the “student-faculty interaction” category were wide-ranging. They included elements concerning emotional support, study skill assistance, academic performance feedback, and assistance with professional goals (see, for example, Appendix A). Of course, these factors often occur in a number of settings. In the same way that the use of Socratic questioning, small group, or large group class discussion imply a level of student-faculty engagement that is significant in the formal sense, the individual relationship between the student and faculty member as student researcher, class tutor, or from the perspective of the professor, co-curricular activity advisor, can be quite different. The findings of the present study demonstrate that there is no one setting that will produce the results one might expect with regard to the enhancement of student character development. Instead, they imply that student-faculty relationships that are defined according to fundamentally different contexts should be assessed independently for their impact.A more sobering analysis can be offered when examining the generic nature of the student-faculty relationship in a small liberal arts institutional setting such as the one where this study was conducted. Institutions of this type pride themselves on low student-faculty ratios and small class sizes that promote more direct involvement between the professor and the student. Student advising in particular, and offering mentorship more generally, is usually held to be an important faculty responsibility, indicative of one’s professional commitment to teaching and service. To the extent that the responsibility of faculty mentor implies that a natural role modeling effect will often take place in such environments, one's assumptions would prove quite questionable in this instance. Whether or not the concept of professor as role model is antiquated, it does appear that the power of professor as role model to effect students' character development can have definite limitations.This study highlights the fact that because the growth of one’s character development does not naturally occur independent of certain variables, the importance of reaffirming an institutional commitment to its enhancement cannot be overestimated. Such an institutional commitment needs to occur at many levels and in many sectors, but is informed through holistic theoretical perspectives that link processes of student learning to student development, as well as cognitive to moral development. Certainly those higher education professionals within student affairs divisions who are most likely to be in contact with students on a regular basis such as residence hall assistants and directors, counseling and advising center staffs, multi-cultural student affairs personnel, and those staff who focus upon religious and spiritual life issues, play an important role in creating the institutional space and support that encourages students to enhance their character development in marked ways. Their role needs to be affirmed and better appreciated. Their responsibilities in offering support and encouragement to students in this realm also need to be more forcefully clarified. In addition, working together with faculty through understanding the logic behind their particular curricular and pedagogical efforts can only help undergraduate students in these matters. Faculty, on the other hand, need to communicate to students that the acquisition of practical wisdom only arises as a result of the exercise of the type of sound judgment that occurs when one exposes oneself to situations that demand personal reflection, social engagement, and a willingness to extend beyond the familiar and comfortable. In short, they need to promote better curricular and co-curricular experiences that assist students in finding those situations that allow them to acquire such wisdom. They also need to view the attainment of practical wisdom as an important value that needs to be affirmed through their teaching, their interactions with students, and by the institution as a whole. Situations that allow students to exercise practical wisdom not only build individual character development, but also encourage the type of ethical awareness that is essential to the cultivation of a democratic citizenry and therefore reflect the very reasons why higher educational institutions exist. Regardless of the specific subject matter that is taught, these are values the entire faculty should profess and encourage.Although the importance of making such connections has been articulated for many decades to student affairs audiences, the present study demonstrates that those practices that would facilitate the routinized establishment of these connections throughout all campus domains have yet to have been fully actualized within the institutional setting under investigation. However, it is also clear that in order for the importance of student character development to be affirmed on an even broader inter-institutional scale, more focused research involving the specific practices that most effectively influence its growth, the conditions under which such practices occur, and the transferability of those practices to institutions with varied structures and cultures, is warranted.

5. Limitations

- The institution utilized for the present study is a private baccalaureate liberal arts university located in the Midwestern United States and serves a diverse and predominately residential student population. The applicability of the findings to other campus settings is unknown. The survey instruments employed were administered to first-year undergraduates in 2004 and 2008 (SIF), and again in 2008 and 2011 (CSS) when the students were seniors. The significance of the findings is best understood when comparing the results with published analyses of larger, survey data that address similar questions.

Appendix A: Content of the Multiple Item Scales

- Student Information Form (SIF)Predisposition to Character1) Attended a religious service2) Becoming involved in programs to clean up the environment3) Developing a meaningful philosophy of life4) Helping others who are in difficulty5) Helping to promote racial understanding6) Influencing social values7) Participating in a community action program8) Performed community service as part of a class9) Performed volunteer work10) Socialized with someone of another racial/ethnic group11) Understanding of othersCollege Senior Survey (CSS)Character1) Ability to get along with people of different races/cultures2) Becoming involved in programs to clean up the environment3) Developing a meaningful philosophy of life4) Doing volunteer work5) Helping others who are in difficulty6) Helping to promote racial understanding7) Influencing social values8) Knowledge of people from different races/cultures9) Participating in a community action program10) Performed volunteer work11) Prayer/meditation12) Raising a family13) Understanding of others14) Understanding of social problems facing our nation15) Understanding of the problems facing your communityStudent-Faculty Interaction1) Advice and guidance about your educational program2) An opportunity to apply classroom learning to "real-life" issues3) Emotional support and encouragement4) Feedback about your academic work (outside of grades)5) Help in achieving your professional goals6) Help to improve your study skills7) Intellectual challenge and stimulationDiverse Peer Interaction1) Dined or shared a meal2) Felt insulted or threatened because of your race/ethnicity3) Had guarded interactions4) Had intellectual discussions outside of class5) Had meaningful and honest discussions about racial/ethnic relations outside of class6) Had tense, somewhat hostile interactions7) Shared personal feelings and problems8) Socialized or partied9) Studied or prepared for class

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML