-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2012; 2(7): 347-355

doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20120207.19

Illustration of Gender Stereotypes in the Initial Stages of Teacher Training

Pilar Aristizabal Llorente 1, Mª Teresa Vizcarra Morales 2

1Departamento de Didáctica y Organización Escolar, Escuela Universitaria de Formación del Profesorado, Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU), Vitoria-Gasteiz, 01006, Spain

2Departamento de Didáctica de la Expresión Plástica, Musical y Corporal, Escuela Universitaria de Formación del Profesorado, Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU), Vitoria-Gasteiz, 01006, Spain

Correspondence to: Pilar Aristizabal Llorente , Departamento de Didáctica y Organización Escolar, Escuela Universitaria de Formación del Profesorado, Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU), Vitoria-Gasteiz, 01006, Spain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In this article we present a study carried out over the period 2009-2010 in the Vitoria Teaching Institute, part of the Basque Country University (Escuela Universitaria de Magisterio de Vitoria de la Universidad del País Vasco [UPV/EHU] ) in which we attempt both to identify the perceptions of the student body surrounding the issue of gender equality and their perceived need to be aware of said issues during the initial stage of their teacher training. In brief, we will look at the underlying gender stereotypes found within the student body at the initial stages of training. We track a trajectory which attempts to define different stereotypes and the way in which people are socialised within these stereotypes; as well as looking at the role the school plays in said socialisation. We provide a case study, the key strategy of which has been to use discussion groups as the way of obtaining information.

Keywords: Initial Stage of Teacher Training, Learning in the Work-Place, School-Students Relationship, Gender Stereotypes

Cite this paper: Pilar Aristizabal Llorente , Mª Teresa Vizcarra Morales , "Illustration of Gender Stereotypes in the Initial Stages of Teacher Training", Education, Vol. 2 No. 7, 2012, pp. 347-355. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20120207.19.

1. Introduction

- Twenty years have passed since the linking of infant and primary education into the single school. Upon planning this study, we aimed to know and comprehend the underlying perceptions and ideas surrounding the issues of gender equality in students in the third year of teacher training; as well as to reflect upon the necessity of being conscious of said issues in the initial stages of training. We wished to focus our investigation on the following questions: have we overcome gender stereotypes or, on the contrary, do we continue to propagate the same sexist frameworks? Which are the expected behaviours from young girls and boys by our students? Are there mistaken beliefs which arise from the stereotypes? How are relations of equality understoof? Briefly, we wished to bring to the surface the opinions and attitudes among our student body, with the aim to allow for future proposals for the improvement of teacher training in regard to issues of gender.

2. Theoretical Framework

- In order to reflect upon gender stereotypes, we must know what the latter are and how they influence the construction ofgender identity – whether masculine or feminine. For ([17]: 113-137), stereotypes constitute the “sum of shared beliefs regarding personal characteristics, usually personality traits, but also certain behaviours, associated with a group of people”. According to[15] and[12], one of the key characteristics of stereotyping is that it determines a certain viewpoint regarding different aspects of reality. Said viewpoints are accepted without questioning and operate in an unconscious manner influencing our thinking, talking, feeling and living mechanisms. That is to say, they condition our rationality, our emotivity and our behaviour. Among the different stereotypes which our thinking can generate, there are sexist stereotypes, those which define woman assuming certain determined roles in her relation to man, and vice versa.[10]. Gender stereotypes are “the sum of thinking processes surrounding personality and behavioural traits of women and men, based on the acceptance of the patriarchal cultural model and the relation of superiority of one and the dependency of the other.’ ([15]: 116-136). In due thanks to feminist studies and investigation, in present day we know much more than we used to regarding the way in which young boys and girls acquire gender roles during the process of socialisation, since the former have exposed that one learns to “be a boy” or “be a girl”. In this manner we appropriate thought and behavioural models which are considered acceptable in out society[6]. Said models are different depending on factors of class, and national and local culture. According to`[13], everything is predisposed in society so that each role can be assumed in a manner which may appear natural, as though the roles were consequence of existing physical differences rather than human intervention. In the process of socialisation, the school, family and media appear as the three large institutions which influence individual identity and the social classification of persons in accordance with sex – converting the biological difference into a social difference. The symbolic representation of what it is, and what it must be, to be a man or a woman, conditions the immersion of each person within society[12] acting within the school as a tool to disseminate and propagate gender roles as assigned with patriarchal society by way of different mechanisms. In patriarchal societies, young boys are encouraged to be active, and to develop their own personal judgement and autonomy. On the other hand, young girls are forced to develop mechanisms which construct a dependent personality, without autonomy and always in service to others. This situation has provoked a partial development of persons, since women acquire abilities, values and attitudes’ related to the private sphere, and men develop those related with the public realm. Consequently, young ladies often do not view themselves as active protagonists of the surroundings they inhabit.For this reason, it is necessary to know the expectations of future educational training as regards expected behaviour from young girls and boys, in order to reflect upon how these influence expectations in the propagation of stereotypes, since, as affirmed by[12], since are born, the image which is projected upon each person conditions his or her adult life. In our society, masculine stereotypes are bound to professional activity and the public realm, attributing certain traits to men such as, activity, aggressiveness, authority, bravery, a commanding stance and an aptitude for the sciences. Furthermore, it is widely affirmed that men are more violent than woman, that they are greater risk-takers, that they repress their feelings, that they speak less about intimate issues, etc. Traits associated with women are activities of care, jealous of privacy and lacking control over power, attributing qualities to them such as passivity, tenderness, submission, obedience, docility, shyness, lack of initiative, tendency to dream, doubt, emotional instability, lack of control, dependency, an aptitude for literature and weakness. In the same manner, it is accepted that women are more intuitive, more fearful and more likely to put in effort[12];[14]. Feminine roles have always been associated with grace and beauty, delivery and devotion, children’s education, fragility and sweetness…[10]. According to[13], teaching operates in a manner where different boys and girls are formed by way of continuous correction of those behaviours which surpass gender norms.[8] collects from different empirical investigations (i.e. from Subirats and Brullet, 1988; Freixás and Fuentes, 1986; Spender, 1982, Stanworth ,1981; Warrington and Younger, 2000 and Francis, 2000), which, in the classroom, girls are spoken to less, they are required to participate less, they are used as examples less, and, in general, they are stimulated less. Similarly, the afore-mentioned research constates that girls dispose of a lesser space for play, their games are less valued and less attention is paid to their explanations regarding their activities out of school. At the same time, often they are asked to take charge of the boys, to pay them attention or to help them with an activity. According to[3], the differences between feminine and masculine communication styles begin at very early stages, at two years of age already girls are solicited for help more often than boys (which is a way of recognising one’s own inability); and at four years of age, in mixed groups, already the boys do not talk, they make comments which distract or perturb and they affirm themselves emphatically. This means that girls and boys learn at a very early stage the patterns of tone, articulation and intonation which “correspond” to those of their gender. Girls and boys are given different physical abilities, but these qualities are complementary and are coupled: control-strength, softness-effectiveness, prudence - audacity, and the difference appears as something natural, without this being necessarily the case at all times. According to Beer (2005, in[16]), “the pattern used to measure girls is the model used for boys. The achievement and mode of functioning of the boys is that which establishes the measure for comparison. In light of that measure, the girls tend to be at an inferior level, since it is usual to male sporting achievement and activity as the unit to measure all other activity by”. Boys and girls interiorise these expectations from teachers, where the obtained result could be the consequence of their own personal effort or of the positive or negative consideration of the teacher. Teachers, in general, place higher hopes on students which demonstrate different attitudes in reference to boys and girls, and that, obviously, influences its results. According to certain studies, boys who do well at school are the “favourites” among teachers, more so than girls which obtain brilliant results. Conversely, girls who are not good students are in a better position than boys, even those which obtain results equally bad to the boys[10]. In this process of socialisation, the school constitutes on of the socialising elements which configures the personality of persons, as well as their manner of feeling and thinking. It is not the only nor the first institution to do, but it asserts huge influence due to the long time which boys and girls spend within her and the special position attributed by society to the school realm. The contents and values passed on in the educational process are of great importance since they influence young persons reinforcing the received culture in the familiar surrounding and supporting – or removing – security and self-esteem[4]. We know that the school does not create the differences between persons of different sex, but it does help to legitimise them. The school is a clear reflection of the society in which we move and in which our students are educated. It has operated within an androcentric model of society which has reproduced itself through the so-called hidden curriculum, which has been propagated in the schooling system unless the teacher training places special emphasis on the questioning, by its students, of gender stereotypes ([12]:133). In the actual school, all formal differences related to a curriculum differentiated by sex have disappeared. Similarly, so have the existing differences in remaining activities, since the same content is offered to boys and girls, but the hidden and, generally, unconscious differences are maintained in all educational systems and they are passed on from the very first stages of school – despite unintentionally – through the hidden curriculum[10]. In this sense,[12] point out that the school can be a tool at the service of the reproduction of social relations; or an instrument to interrupt said relations and form the bud of new relations which are not marked by inequality nor reinforce social disadvantages. The transformational possibility which the school holds lies in visualising that which is presented as impossible in the curriculum. Special attention would have to be paid to the educational contents which are transmitted via the school and the processes of social relating which are developed there. In order to realise a critical revision of sexist stereotypes found in school content it is necessary to analyse the models which are passed on in the school via the images, content and language of school text-books[12]. Sexism exists in text books, in those instances where images and allusions to women and men are unequal, when the symbolic representation of the feminine is discriminated against by its scarce appearance in the different text books, when images and contents harbour sexist stereotypes, and when women and woman’s world does not appear or appears in a distorted manner. In this sense, one of the “forgotten” contents in text-books is that of housework. Neither in history, nor science, nor technology books is it, for example, mentioned what types of ovens, kitchen, fridges, driers, or cleaning and ironing systems have been utilised in order to reach the current sophisticated systems. Let us bear in mind that, currently, young generations –both girls or boys– do not receive any formation surrounding those types of knowledge which, in a discriminatory manner, have traditionally been associated with women, and which form necessary knowledge for personal autonomy (Lomas, in[2]). What lies behind this is the co-educational school holding as its objective to eradicate gender stereotypes, overcoming social differences and hierarchies between boys and girls. Faced with the choice of a professional career, stereotypes define which activities are appropriate for some and for others, and as such they will influence professional development[9]. In 2010 the European Commission presented the manner in which various European countries accommodate inequality between men and women within education. In this report it can be observed that differences between the sexes persist in subject choice as well as grades, and it indicates that traditional stereotypes continue to be the main obstacle for gender equality within education[7]. It is necessary to discover and demonstrate that, despite the fact that it may seem that the principles of equality are primary within schools and that we have norms and regulations enacted which seek educational equality; in reality, there are multiple hidden forms of discrimination and reproduction of stereotyped models. Due to this, it is necessary to understand preconceived, often false, ideas surrounding women ([12]:131).

2.1. Method

- We are faced with a case study which attempts to reach the persons implicated in the investigation, in order to comprehend their reflections, motivations andinterpretations of their content and in order to view reality through their eyes. Case studies facilitate the immersion of a determined content in order to perceive the difficulties and opportunities which present themselves during a process. The aim of this investigation is to analyse the case of the University of Vitoria teacher training and ask ourselves what occurs in said context, via its protagonists.The strategies for data collection have fundamentally been a semi-open questionnaire and discussion groups carried out with students and teachers.As regards the procedure followed in the investigation: in order to operate the told for data collection it was necessary to be aware of previous research surrounding this subject, and consequently the tools for investigation have been constructed based upon those used in previous research, adapted for our circumstances and our object of study. We used questionnaires in order to initially approach the issue, and in order to guide the discussion groups. Following this we collected the questionnaire results and transcribed the recordings gathered in the discussion groups. As regards analysis and data handling, a content analysis has been carried out through hierarchic hermeneutic categories, which have been codified and ordered with the help of software NVIVO 8. Lastly, a report was composed outlining the data gathered with the different instruments. This process has not been linear at all times, in some cases we have had to do so retrospectively. Context and participants in the investigation: the investigation is carried out in the University of Vitoria teacher training, and the participating persons are part of the latter. It is a small centre which offers certain advantages, since we all know each other and communication is thus easily enabled. The number of women and men in the faculty is fairly balanced: 42 men and 36 women, of which 4 men and 11 women partook in the discussion groups. There are three specialisations in the Faculty, Infant Education, which is aimed at teachers which will develop their profession with girls and boys of 0-6 years; Primary Education, aimed for training teachers of girls and boys between 6 and 12 years of age, and Physical Education which aims to train teachers specialising in physical education for boys and girls of 6 to 12 years. Teaching degrees are much feminised, in that, for example, in the course matriculation 2009-2010, the percentage of women matriculating in Infant Education was 92% and in Primary Education 70%. However in Physical Education, the data is inverted as we see a 68% male matriculation. In this investigation the participants of the third year for all three diplomas take part. We were particularly interested in the collective opinion of male and female students about to finish their degree, since we wanted to know their opinion and their attitudes towards this issue, as well as the deficiencies which they detected in the degree. 217 questionnaires were collection and 18 discussion groups were carried out. The triangulation of data: in order to quality-assure the research we used the triangulation method of informants, instruments and investigators, since we were contrasting the same circumstances from different viewpoints.

2.2. Results

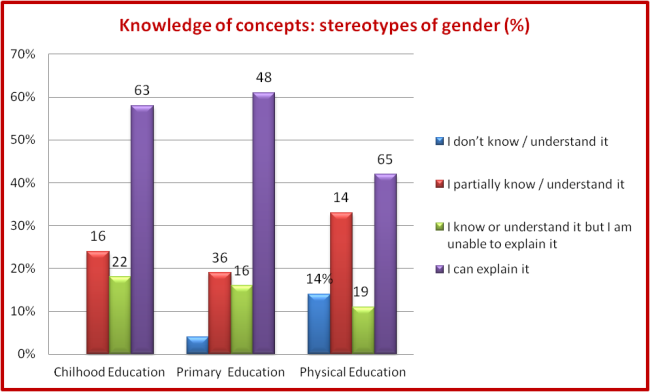

- As regards stereotypes, when asked what they see in the school, in the first instance in the majority of groups are of the opinion that there are no stereotypes present within our Faculty. However, we have been surprised to see how, in their responses, there appear various stereotypes which we have encountered in the scientific literature, some of which related to the physical and personality traits of men and women, as well as others, related with study or professional choices. When we asked them, via the questionnaire, if they could define stereotypes, in the majority of cases, they say that they know what they are and they could define the concept, as seen in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. knowledge of oncepts by specialisation: gender stereotypes |

| Figure 2. Presence of gender stereotypes in Teacher Training Faculty at the University |

| Figure 3. present stereotypes in the Education Faculty |

3. Conclusions

- Despite the discourse of equality which surrounds us, we are immersed in a patriarchal society where androcentricity invades all realms. In that which concerns us, it is clear that androcentricity is anchored within the institution of the school. It invades language through which we communicate, through which we interpret the world, it is present in the material we utilise which ignores half the population, women; it is present in the play areas where girls and boys share a great part of their time and in relations of dominance / subordination / dependency which is established between them. We find them even in the patterns of relation within the very student body of the university which reflect the communication styles of dependency/dominance and which they themselves confess to be the case (us girls are quieter, boys get involved more, they’re louder, they seek attention).It is present in the schooling organisation, which makes women settle in the lower levels of the educational system and we will continue to witness the tendencies of the latest matriculations, where particularly in Infant Education (0-6 years) practically 100% of students are women. We will need to ask ourselves why, after almost two centuries, this continues to be the same, and ask what occurs with the view of certain professional and academic choices seen as “appropriate” for each gender. In this manner we can conclude this article stating: Despite the discourse of equality which surrounds us, we are immersed in a patriarchal society where androcentricity invades all realms. In that which concerns us, it is clear that androcentricity is anchored within the institution of the school. It invades language through which we communicate, through which we interpret the world, it is present in the material we utilise which ignores half the population, women; it is present in the play areas where girls and boys share a great part of their time and in relations of dominance / subordination/dependency which is established between them. We find them even in the patterns of relation within the very student body of the university which reflect the communication styles of dependency/dominance and which they themselves confess to be the case (us girls are quieter, boys get involved more, they’re louder, they seek attention)... It is present in the schooling organisation, which makes women settle in the lower levels of the educational system and we will continue to witness the tendencies of the latest matriculations, where particularly in Infant Education (0-6 years) practically 100% of students are women. We will need to ask ourselves why, after almost two centuries, this continues to be the same, and ask what occurs with the view of certain professional and academic choices seen as “appropriate” for each gender. In this manner we can conclude this article stating:1. In general, people who study in the Faculty of Education at the University of Vitoria do not see stereotypes for what they are, unless this subject is specifically targeted and elaborated upon. A lack has been thus detected, in the present study programmes of this centre, and a necessity for formation and heightened sensitivity has been recognised. 2. Just as it occurs in other investigations, certain behaviours and characteristics seen as gender-appropriate are attributed to each sex, attributing to the masculine all that is related with strength, power, leadership... and to the feminine, sweetness, softness sensitivity and care. 3. Stereotyped beliefs which hold certain behaviours belong to one sex and others to the other provoke the fact that, if we don’t establish a concrete effort towards a heightened sensitivity and education regarding gender during the initial stages of teacher training, our future teachers will understand it as natural that girls and boys hold differentiated characteristics, and thus they will continue to transfer the values of patriarchal society within schools. 4. The choice of subjects of study seems conditioned by gender stereotypes. In this manner, girls choose to specialise in Infant Education since it is associated with care and the private sphere, whereas boys choose Physical Education, because it is associated with physical aptitude and movement. Yet, whereas in Physical Education there has been a rise in the female participation, the same does not occur with males and Infant Education.Having gathered these conclusions with a view to the future of teacher training, we believe that there are various lessons to be learnt, since it is necessary to improve the professional orientation in order to face the problem of stereotyped decisions, with a greater conscientiousness regarding the great influence which gender stereotypes hold; and with better tools for this purpose[7]. Within the initial stages of teacher training, it is necessary and urgent to include content which helps us visualise those discriminations which, today, we may be subject to. In other words, we must “train the eye” for this to be possible. In light of the contributions gathered in the discussion groups, we think that the practical research groups can be an invaluable observatory in order to heighten consciousness regarding these issues. There are numerous guides and manuals which can facilitate this task. It is the job and responsibility of the University Educational Faculties to put these tools in the hands of our student and teaching body. Despite the fact that we are conscious that the school, on its own, cannot change society’s values, we are also conscious that virtually 100% of the population experiences schooling of some form and within her our future teachers and governing bodies are formed. In this manner,[13] tells us that “The educational system cannot, on its own, eliminate the differences contained within society, but the change must occur at some point or moment... and education is an essential step towards said change” We are convinced that by offering an adequate education and the necessary tools for intervention to new teachers, we can influence the advancement towards a more egalitarian society. We believe that it is time to break this chain and for this purpose, it is a necessary task to detach from the importance given to stereotypes as configurating factors of reality; in order to delegitimize patriarchal power based on prejudice and privilege[12]. Within Faculties of Education we hold the social responsibility of embarking these issues with the end of supplying future teachers with the tools to face the discriminatory situations produced in schools both within and outside the classroom. We’re onto this!

References

| [1] | Arenas, M. G. (2006). Triunfantes perdedoras: investigación sobre la vida de las niñas en la escuela. Barcelona: Graó. |

| [2] | Ballarín, P., Lomas, C., Simón, E., Solsona, N., & Tomé, A. (2007). Guía de buenas prácticas para favorecer la igualdad de hombres y mujeres en educación. Sevilla: Consejería de Educación de la Junta de Andalucía. |

| [3] | Bengoechea, M. (2005). Modelos comunicativos y de relación. In SARE Nazioarteko Kongresua: Egungo neskak, etorkizuneko emakumeak. Donostia: Emakunde. |

| [4] | Carbonell, J. (1996). Educación sexista y coeducación. La escuela entre la utopía y la realidad. Diez temas de sociología de la educación. Barcelona: Octaedro. |

| [5] | Carrasco Macías, M. J. (2007). La dirección escolar desde la perpectiva de género. In M. G. Arenas (ed.) Pensando la educación desde las mujeres, (pp. 71-90). Málaga: Atenea. |

| [6] | Espinosa Bayal, M. A. (2005). Generoa eta ereduak familian. In SARE. Nazioarteko Kongresua: Egungo neskak, etorkizuneko emakumeak (pp. 31-40). Donostia: Emakunde. |

| [7] | European Comision. (2009). Report on equality between women and men 2010 doi: 10.2767/86519 |

| [8] | Francis, B. (2005). Las niñas en el aula. Nuevas investigaciones, viejas desigualdades identidad de género en el marco escolar In SARE Congreso Internacional: Niñas son, mujeres serán (pp. 55-67). Donostia: Emakunde. |

| [9] | González Lopez, I. (2009). La orientación académica y profesional en clave de igualdad. Participación Educativa, 11, 110-121. |

| [10] | Red2Red Consultores. (2004). La situación actual de la educación para la igualdad en España. Madrid: Instituto de la Mujer. |

| [11] | Sánchez Bello, A. (2002). El androcentrismo científico: el obstáculo para la igualdad de género en la escuela actual. Educar, 29, 91-102. |

| [12] | Sanchez Bello, A. & Iglesias Galdo, A. (2008). Curriculum oculto en el aula: estereotipos en acción. In R. Cobo (ed.). Educar en la ciudadanía. Perspectivas feministas (pp. 123-150). Madrid: Los libros de la Catarata. |

| [13] | Subirats, M. (2007). De la escuela mixta a la coeducación. La educación de las niñas: El aprendizaje de la subordinación. In A. Vega Navarro (coord.). Mujer y educación. Unaperspectiva de género (pp. 137-148). Málaga: Aljibe. |

| [14] | Taberner Guasp, J. (2009). Soziologia eta hezkuntza: Hezkuntza-sistema gizarte modernoetan funtzioak, aldaketak eta gatazkak. Bilbo: UPV/EHU. |

| [15] | Tomé Gonzalez, A. (2007). Las relaciones de género en la adolescencia. In A. Vega Navarro (coord.). Mujer y educación: Una perspectiva de género (pp. 116-136). Málaga: Aljibe. |

| [16] | Vizcarra, M.T.; Macazaga, L. & Rekalde, I. (2009). Eskolako kirol lehiaketan neskek dituzten baloreak eta beharrak. Bilbao: Emakunde. |

| [17] | Yzerbyt, V. & Schadron, G. (1996). Estereotipos y juicio social. In R. Y. Bourhis & J. P. Leyens (Eds.). Estereotipos, discriminación y relaciones entre grupos (pp. 113-137). Madrid: McGraw-Hill. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML