Joyce R. Jeewek 1, Cynthia G. Gerwin 2

1College of Education, Benedictine University, Lisle, IL, USA

25th grade teacher, Hall Elementary School, Glendale Heights, IL, USA

Correspondence to: Joyce R. Jeewek , College of Education, Benedictine University, Lisle, IL, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

This study examines the impact parents/ family involvement and modeling may have on the academic performance and attitude a child has towards reading. Participants include third, fourth and fifth graders from a small Title I school in a suburb west of Chicago. A qualitative descriptive survey, which includes a commitment to participate in a family involvement reading intervention program, is given to every student/family. Due to the lack of students/families willing to participate in an intervention program, qualitative survey results and quantitative reading data is exclusively examined to measure impact of family involvement in the reading curriculum. Educators can use this model to develop their own questionnaires to gather family information. Background information can help teachers understand their students better in order to differentiate instruction in the classroom and help identify possible curricular changes needed to further promote lifelong readers.

Keywords:

Parental Involvement/Modeling, Literacy, Student Achievement

1. Introduction

As educators we often seek answers by asking questions. In order to differentiate instruction we can find useful information about our students by using interest inventories or attitude surveys. To understand her students more in depth, this research looks at one teacher’s attempt to find out about her students’ reading background by asking parents to provide information that may help teachers planning for student-centered instruction.

2. Background

2.1. AliterateSchooltime Readers

“It is highly interesting to our country, and it is the duty of its functionaries, to provide that every citizen in it should receive an education proportioned to the condition and pursuits of his life.” These words, spoken by Thomas Jefferson[11], provided the foundation for a new system of education in the United States now referred to as public education. The goal of this new system, public education, was also clearly defined by Jefferson[12] when he said these words, “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.” Schools need to create lifetime readers, not produce aliterate school time readers, people who know how to read, but choose not to read literary materials. When lifetime readers graduate, they continue to read and educate themselves throughout their adult lives instead of knowing how to read and choosing to never pick up a book after graduating. Lifetime readers are also lifetime learners who seek to gain knowledge and understanding, which becomes our nation’s ultimate weapon to preserve freedom and democracy while destroying ignorance, poverty and despair[20]. Finally, lifetime readers model reading and learning behaviors that can be passed on to their children.

2.2. Family Involvement

The level of literacy achievement that is necessary to be successful in today’s complex society, can no longer be accomplished within the confines of the public education system. New partnerships need to be formed to combat stagnant levels of reading achievement – partnerships that include parents and family members as well as teachers and schools. Literacy achievement, however, can be an intergenerational issue. Parents cannot assist in educating their children if they do not know how to model reading behaviors or do not believe in the value of reading, so the cycle continues. Family involvement is also often measured in traditional terms imposed by school systems that are founded on the values of the white middle class. Because of this, parents and family members who are capable of supporting literacy achievement in non-traditional ways are not recognized and are often negatively criticized for their lack of accountability by teachers and schools[18]. When students enter kindergarten they come with 100% enthusiasm to read for pleasure every day, among fourth-graders, 45.7% read something for pleasure every day and in eighth-grade that percentage drops to 27% reading daily for pleasure[4]. Gallagher[6] refers to these drops in percentages as an “unfortunate shifting of reading attitudes – from enthusiasm to indifference to hostility”. Human beings repeat activities which are pleasurable and avoid activities which are not. School time reading has become a mundane and often unpleasant activity for many young readers; therefore, although students learn to read, they become aliterate, choosing instead not to read. Reading and sharing that reading with a family member is often perceived as a pleasurable experience – which translates into lifelong reading and learning[20].Simply put, achievement in literacy cannot be accomplished within the confines of the school alone. Partnerships must be forged between schools, communities and family members. In order to form healthy partnerships that are effective, teachers need to not only aid family members in resolving their issues with literacy, but need to positively reinforce all literacy activities, no matter how untraditional. The lifelong experience of reading daily, and feeling pleasure from that experience, is the single largest predictor of student achievement across the board, which translates into lifetime achievements as well as success in reading[20].

2.3. Creating Lifetime Readers

While the goal of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001[1] is admirable, the sheer volume of standards that are mandated in the curriculum, coupled with the accountability issues facing schools, has forced teachers to cover reading using surface structure methods found in many canned reading programs (example - basal series) that conform to standardized tests. Standardized tests may measure some level of reading achievement, but do not measure reading interests and the increased level of aliteratebehavior by today’s students. Kindergarteners showing a higher level of interest and enthusiasm towards reading have parents who reported reading to them daily and living in a print-rich environment compared to kindergarteners demonstrating a low level of interest in books[18]. Several research studies support the theory that socio-economic status is not the key predictor of reading achievement; it is the significant relationship between the home literacy environment and parental values and attitudes towards reading[18]. Home literacy environments can include traditional literacy activities such as reading aloud and parents modeling consistent reading behaviors, or non-traditional literacy activities such as speaking in longer or more complex sentences (increases listening vocabulary), creating stories to go with picture books (for parents who cannot read or who read a different language) and taking children on outings (museums, libraries, etc.) that promote literacy and learning[2].Global complexities of our society require a higher level of reading achievement for success; therefore, we need to pursue new avenues for improving literacy achievement other than just in the classroom. School interventions alone cannot overcome the lack of parental involvement[20] The home environment provides the second largest venue for education to take place. Although the largest gaps in reading achievement can be found in low socio-economic homes; even children of professionals do not find reading a pleasurable experience, and can benefit from parental involvement[16].Determining the correlation between parental involvement and student reading performance does impact the future of students in more ways than one. Not only will reading achievement improve, but student achievement in every subject area as well. Achievement is a pleasurable experience that promotes lifelong learning and students who become citizens that are not aliterate or ignorant. Since the largest drop in reading for pleasure occurs in the intermediate grades[20], studies such as this, can be completed to help determine if the drop can be averted when family involvement interventions are put into place in the intermediate grades. Studies such as this can also aid teachers and schools in determining which family interventions most affect changes in reading achievement.

2.4. Family Involvement Issues

For teachers and schools to develop effective partnerships with families, it is critical they work with families to emphasize and support strengths instead of becoming condescending to families by focusing on their issues, which are often seen as failures. Teachers and schools cannot eliminate uncontrollable factors, but a partnership approach can often mitigate their effects. When parents feel good about their school involvement, instructional efforts and school partnerships, they tend to have higher expectations for their children. Differences between teachers, schools and parents, with regard to expectations and misunderstandings can lead to uncertain, tenuous; sometimes even hostile, relationships[19]. Sadly, the families that are most in need of family/school partnerships often are provided with the least access to these partnerships[17].Intergenerational illiteracy which is a socio-culturalphenomenon whereby the conditions of the home environment inadvertently hinder a child’s literacy development is an issue which affects a family’s involvement[2].Elements of intergenerational illiteracy include: lack of strong language examples, little family interaction and poor print materials. Within the next two decades, over half of the U.S. school population will be members of language, ethnic and socio-economic minority groups[15].Many of the children within these minority groups are being labeled ‘at-risk’ or ‘developmentally delayed’ (below grade level performance) according to standardized test scores. All too often, the real issue is not that they are performing below grade level, but that their discourse (ways of combining, words, thoughts and values, so as to engage in a specific social setting or activity) matches that of their family or community unit which varies greatly from the school culture which is centered on white middle-class values. Teachers and schools must always be mindful of the fact that a family is a child’s first and most important teacher, and their values and cultural beliefs may actually be similar to that of the schools despite the differences in discourse.Reading InstructionLiteracy development begins at birth; therefore, so too should a family’s involvement in literacy development. The more experiences children have with the concepts of print, the more a child’s cognitive skills in reading and writing will develop. Although reading is often taught in isolation of writing in a formal educational setting, both are closely intertwined. Van Peeren[21] discusses the theories of developmental psychologists Piaget and Vygotsky and their relevance to the discussion of literacy development. Literacy is a cognitive skill that can be discovered, so children construct their own ideas about literacy through active participation, according to Piaget. Vygotsky’s theories incorporate how modeledbehaviors and support, often referred to as scaffolding, from adults encourages children to refine their ideas about literacy to meet more conventional standards[21]. Parents, family members and teachers can participate in this process with children to further develop a child’s metacognition (thinking about ones thinking) in literacy.Fostering literacy development and surrounding a child with a print rich environment can greatly aid a child’s growth in literacy. During the intermediate grades, however, the previously acquired reading skills (learning to read) begin to become more complex and refined (reading to learn). In third grade (8-9 years old), refining skills include: final reinforcement of the use of decoding strategies and self-correction, focus on improving fluency and surface structure comprehension. Students should have the ability to read independently for meaning with less attention to decoding, and begin to see a connection between reading and writing, as well as see themselves as readers and writers[21].The following year, in fourth grade (9-10 years old) there is continued focus on improving fluency and increasing the level of complexity with comprehension instruction using a wider variety of reading materials. Students develop a deeper understanding of metacognition. As students become more fluent and read more challenging materials, increasing vocabulary instruction is necessary, especially in content areas[5].Finally, in fifth grade (10-11years old) students should be reaching maximum fluency levels; therefore, the focus continues to shift towards deep structure comprehension skills through the use of novel studies and increased use of non-fiction materials. Students continue to refine metacognitve skills which will aid them in focusing on specific areas for improvement. Due to the increase in content area instruction, academic vocabulary becomes more critical, as well as the transfer of reading strategies to all content areas[5].If children begin elementary school without strong literacy skills, they are at risk of accomplishing minimum grade level standards of achievement which serves to dampen the motivation to become a lifelong reader[13]. Risk of failure increases exponentially when a child reaches the intermediate grades. As mentioned above, by third grade it is a grade level standard that the primary reading skills are in place, and the student is ready to move onto more complex literacy skills like connecting reading with writing and deep structure comprehension. So, the literacy skills a child brings with them when they enter elementary school from years of family involvement creates the foundation necessary for future literacy achievement and family involvement in the middle grades. However, it becomes difficult to build structure in the middles grades without a strong foundation from the previous grades.

3. Methodology

3.1. Approach to the Study

Various methods of approaching research in the social sciences are used. The predominant choices are qualitative, quantitative or a mixture of both qualitative and quantitative. Creswell[3] discusses three criteria to determine which approach should be utilized: the research problem and/or purpose of the study, personal experiences of the researcher and the intended audience. There are several prevailing features in both approaches to research. Qualitative research emphasizes the importance of looking at the correlation between variables in a natural setting. As the researcher gains new insights during the research process, the questions can be refined in order to provide the researcher with the means to judge the effectiveness of a particular program or practice[14]. Grounded theory, which is an emergent research process, is rooted in qualitative research. Because the researcher is guided by questions, instead of preconceived assumptions in the form of a hypothesis, the researcher can follow the data that emerges with a more open mind. According to Creswell[3], the answer to the question, “How is this program doing and can it be more effective?” often does not lie in a single truth formed into a hypothesis. Instead there may be multiple truths or perspectives that have equal validity; therefore, the goal of a qualitative study is to reveal the multiple perspectives, so as many as perspectives as possible can be addressed in when the program is adjusted.

3.2. Examining Relationships Using Questions

The purpose of this action research study is to improve student literacy achievement by exploring the impact of family involvement, specifically to evaluate the current family literacy curriculum and a pilot intervention program being considered as an addition to the curriculum. A determination was made, as a result of the collaborative efforts of the researcher and the principal of the participating school, to use questions, instead of a stating a hypothesis. This choice allowed for multiple perspectives to be heard and for the emergence of a predominant theory related to the correlation between student achievement and family involvement, which can be tested through empirical studies at a later date. Questions also allowed for a more in depth understanding of the students, their families and their response to the family literacy.1. To what level can reading scores be increased with family interventions in place?2. To what level can reading scores be increased without family interventions in place?3. Is the dramatic drop in the intermediate grades daily reading habits/reading achievement correlated to family involvement in reading?4. Can the dramatic drop in the intermediate grades daily reading habits/reading achievement be positively altered in the intermediate grades, or does the intervention need to take place sooner?

3.3. Participants

This study was performed in a collar county outside Chicago in 2009. The district is relatively small with four elementary schools that feeds into one middle school. Students attend high school in a different district. Data was collected at one of the four elementary schools during the spring semester of the school year in order to determine reading habits and parental reading involvement with their children. Total enrollment of the school is approximately 400 students. Subjects of this study include sixty third grade students, sixty fourth grade students and sixty-five fifth grade students. Student enrollment in this school ranges in ethnicity: 16.9%White, 18.6% Black, 48.9% Hispanic, 12.7% Asian/Pacific Islander and 3.0% Multiracial. Due to the high population of Hispanic students, the school also has a high percentage of Limited English-proficient students (17.6% - compared to the state average of 7.2%). Two of the four elementary schools in the district are Title I schools. Title I is a section of the United States federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act that is helps school districts financially to provide resources forlow-income students who are at risk of failing in school. Generally,for a school to qualify as a Title I school, 40 percent of its total enrollment must come from low-income families. This is often determinedexamining the number of students who qualify for free or reduced lunch programs [10].The participating school is classified as a Title I school with 35.7% Low-Income (compared to the state average of 40.9%) and a Mobility Rate of 33.1% (compared to the state average of 15.2%). There is also a Chronic Truancy rate of 3.9% (compared to the state average of 2.5%). Parent contact levels are at 100.0%[10].Although the Attendance Rate is slightly lower than the state average, the corresponding Chronic Truancy rate and Mobility Rate are quite a bit higher. Despite these statistics, and the higher levels of Low Income and Limited English-proficient students, most of the academic and school/teacher characteristics are conducive for stable-to-high academic achievement. The special needs population is approximately 9.9%. The teaching staff averages approximately 12.4 years of experience with 62.0% holding master’s degrees or above. The average teacher salary is $59,939 which is slightly higher than the state average. The average class size is 22 students which closely matches state averages[10].Reading achievement in the intermediate grades at the school where the study is being conducted is low and relatively stagnant. As a Title I school, a family literacy curriculum is required and consists of a Family Literacy Night in the fall. A limited number of parents take advantage of the available parental involvement opportunities such as volunteerism, parent teacher conferences and boosters. This study was developed to evaluate the current family literacy curriculum and various forms of parental involvement in relation to their impact on student achievement. A family intervention program called, Building Bridges to Literacy [22], created for the purposes of this study, is being considered as a pilot program. If Building Bridges to Literacy successfully impacts student achievement and positively improves attitudes towards reading, the program will be added to expand the existing family literacy curriculum.

3.4. Instrumentation

Questionnaires and curriculum were specifically developed for this study and the forms include: the initial Questionnaire for Parents, the family intervention program (Building Bridges to Literacy) curriculum with corresponding Parent Activity Log and the post-program Questionnaire for Parents. DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) scores were used as a measure of student reading achievement to determine any correlation between survey data on family involvement and student reading achievement. The initial Questionnaire for Parents, which includes a Parent Consent Form, consists of twenty-two questions covering demographics, reading and literacy activities, student achievement expectations, modelingbehaviors and a commitment to participate in the Building Bridges to Literacy program, with space for additional write in comments. Responses to the parent questionnaire are cross referenced the corresponding student’s benchmark ORF scores.

3.5. Data Analysis

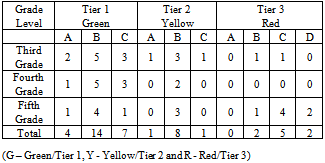

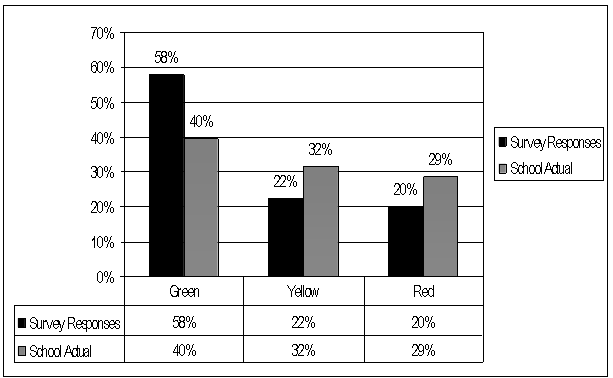

The purpose of the data analysis is to find predominant theories and/or correlations between variables which will increase understanding and drive further research. Results of the initial Questionnaire for Parents (survey) are separated into five main categories: Sample Demographic, Home Environment, Expectations, Involvementand Miscellaneous. All five categories contain both qualitative (comments from the survey) and quantitative (numerical tabulations of responses to specific questions) data. Whenever possible, survey data is compared to reading achievement levels based on DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) scores in the form of the Response to Intervention (RtI) Problem Solving Triangle Model: Green/Tier 1 – students are performing at grade level, so no intervention is necessary; Yellow/Tier 2 – students are at some risk, intervention is necessary to reach grade level performance and Red/Tier 3– students are at extreme risk, multiple interventions are needed to reach grade level performance. Optimal percentages for student reading achievement using the RtI Problem Solving Triangle Model are as follows: Green/Tier 1 – 80% of the student body, Yellow/Tier 2 – 15% of the student body and Red/Tier 3 – 5% of the student body. Uses a multi-tiered method which provides services and interventions to students at increasing levels,the Triangle Model is a response to intervention approach which relies on progress monitoring and data analysis. Student progression is used to make educational decisions, including possible determination of eligibility for exceptional education services. Usually interventions for students fall within three tiers. Tier I (green tier) interventions consist of a general education program based on evidence-based practices; Tier II (yellow) interventions involve more intensive, relatively short-term interventions; and Tier III(red) interventions are long-term and may lead to special education services[10].The Sample Demographic category includes an analysis of socio-economic status of the participants, because historically, socio-economic status has been used to predict reading achievement. For example, low-income students are typically struggling readers; therefore, there should be a higher number of low-income students in the Red/Tier 3 than in the Yellow/Tier 2 or Green/Tier 1. Students from families with high-income are typically better readers, so their numbers should be higher in the Green/Tier 1. Research cited earlier demonstrates that socio-economic status alone is not the most valid predictor of student reading achievement, but rather the extent to which families play a role in the following three areas: creating a home environment that supports and encourages learning; setting high, yet realistic, expectations for achievement, and involvement in a child’s education at home, school and in the community[8]. Since Home Environment, Expectations and Involvement are key predictors, they are included as categories in the Results. A category, Miscellaneous, is also included to record data that may not have fit into the first four categories, but is worth noting in the Results.Surveys returned during the allotted time frame for determining participants in the Building Bridges to Literacy program did not include enough respondents interested in participating in the program. So, the Building Bridges to Literacy program was cancelled and subsequent data from that program not reported. It is worth noting, however, that quite a few additional surveys were returned after the allotted timeframe that would have included enough participants to hold the Building Bridges to Literacy program. Despite having enough participants, many of the participants could not commit to all four weeks, so the program still would not have been able to run under optimal conditions.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Demographic

Third, fourth and fifth grade students participated in the study. Of the sixty students in third grade, seventeen returned a completed the survey. Twelve of the sixty fourth graders and sixteen of the sixty-five fifth graders returned completed surveys (initial Questionnaire for Parents). The highest percentage of surveys returned was in third grade with 28.33%and the total percentage of surveys returned was slightly lower at 24.32% (See Table 1a).| Table 1a. Sample Demographic -Total Number of Students/Number of Surveys Returned |

| | Grade Level | TotalStudents | Number ofSurveys | PercentageReturned | | Third Grade | 60 | 17 | 28.33% | | Fourth Grade | 60 | 12 | 20.00% | | Fifth Grade | 65 | 16 | 24.62% | | Total | 185 | 45 | 24.32% |

|

|

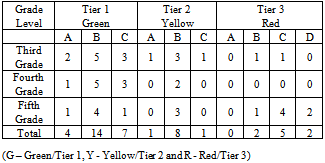

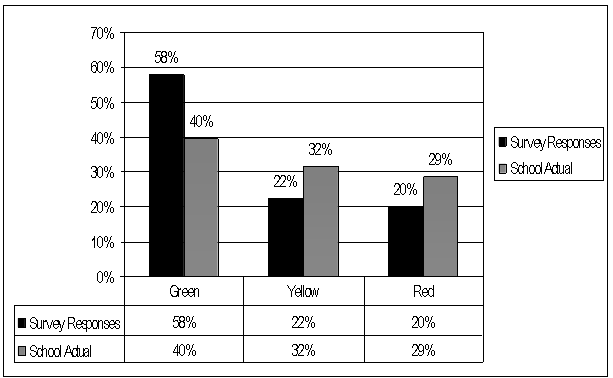

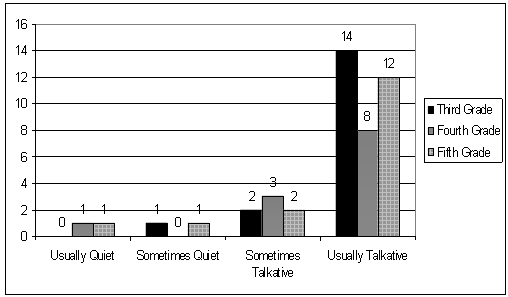

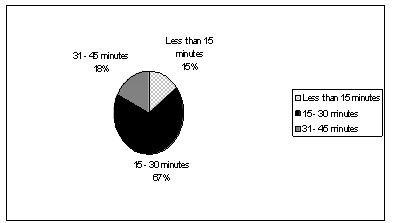

A comparison was made between the reading achievement of those who participated in the survey and the school’s actual percentages in the RtI Problem Solving Triangle to determine if the survey sample accuratelyrepresented the school’s actual population.It should also be noted, that the school’s percentages are significantlybelow optimal RtI Problem Solving Triangle percentages (See Graph 1). | Graph 1. Sample Demographic -RtI Percentages for Survey Responses/School’s Actualy |

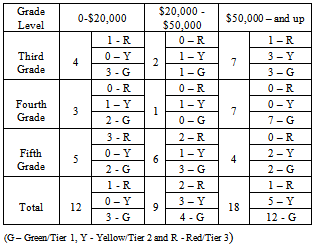

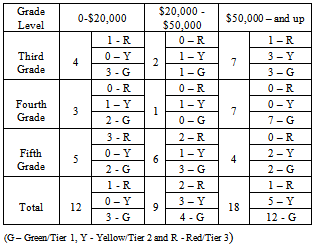

There was a disproportionate number of Green/Tier 1 responses returned.Survey Question 2 asks parents to record the range that most closely matched their family’s household income (See Table 1b).| Table 1b. Sample Demographic –Household Income Ranges |

| | Grade Level | 0-$20,000 | $20,000 -$50,000 | $50,000 and up | NoResponse | | Third | 4 | 2 | 7 | 4 | | Fourth | 3 | 1 | 7 | 1 | | Fifth | 5 | 6 | 4 | 1 | | Total | 12 (26.67%) | 9 (20%) | 18 (40%) | 6 (13.33%) |

|

|

The 0-$20,000 income range is chosen, because of its correlation to the qualifying criteria for the Free and Reduced Lunch Program. The school’s Free and Reduced Lunch population is 35.7% which is approximately 9% higher than the sample demographic of the survey respondents.Of the participants that responded to Survey Question 2, the totals are analyzed to determine household income levels as they correlated to student reading levels for comparison (See Table 1c).Table 1c. Sample Demographic –Household Income/Student Reading Level

|

| |

|

The most notable result is the number of students performing at grade level in the low-income range.

4.2. Environment

Questions 11 and 12 determine the availability of print materials in the home by asking participants if they take their child to the library, and/or purchased books from books stores, book fair and garage sales. Since both questions are similar in nature, and since the results to both questions were almost identical, they have been averaged for ease of reading in the table below (See Table 2) which compares key characteristics of the home environment to student reading levels. Although thirty-six respondents visit the library to check out books and/or purchase books, the accessibility to printed materials has not translated to student achievement with 44.4%not reading at grade level.Survey Question 13 asks participants if they have a subscription to a bi-weekly or monthly publication like a magazine. Seventy-one percent of the respondents do not have a subscription. Based on the responses to Survey Questions 11 and 12, it would seem there are more literature based print materials in the home.Table 2. EnvironmentLibrary & Book Purchases/Student Reading Level

|

| |

|

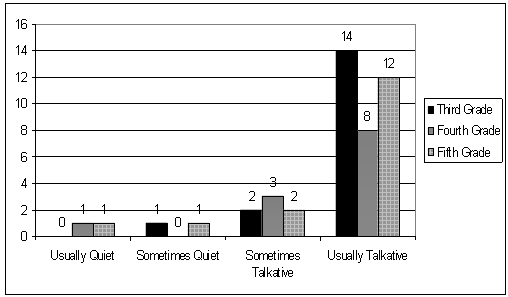

A more detailed response on the survey would be necessary to determine the validity of that assumption. Another question placed under the Environment category is Survey Question 16 which asks participants to rate how talkative they perceive themselves to be with their child (See Graph 2). | Graph 2. Environment: Parent Perceived Communication with Child |

Seventy-six percent rate themselves as “Usually Talkative” with their child.

4.3. Expectations

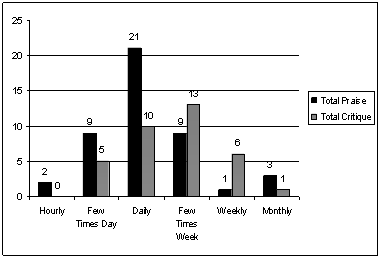

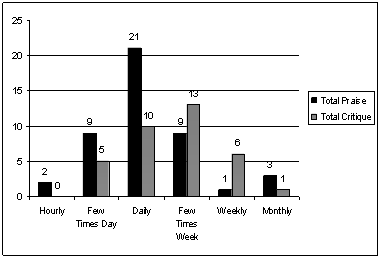

When students move from second grade to third grade, expressions of student achievement also changes from a Pass/Fail system to letter grades. Parent expectations for student achievement; therefore, are overtly expressed in terms of acceptable letter grades. Survey Question 15 asks, “What is the lowest grade you are comfortable with your child receiving on his or her report card?” (See Table 3).The data demonstrates a higher level of parental expectations for students in the Green/Tier 1 group than in the Red/Tier 3 group.Another way parents express their expectations for their child’s achievement is slightly more subtle than the letter grade issued on their child’s report card. It is the consistent praise and/or critiques given to their child on a daily basis. When exploring parental expectations and their impact on student achievement, perceived praise and critiques are a critical component (See Graph 3).Table 3. Expectations: Student Reading Level/Parent Grade Expectation

|

| |

|

| Graph 3. Expectations: Number of Praises to Critiques |

Perceptions of participants’ responses to this question show two times as many praises compared to critiques on a daily basis, yet over the long-term, the praise to critique ratio seems to move more towards a 1:1 ratio. Optimal ratios specify 4 praises to 1 critique.

4.4. Involvement

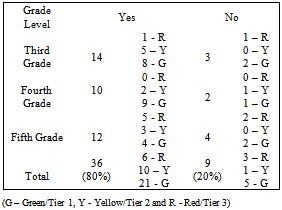

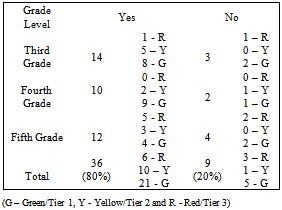

Survey Question 7 asks participants to respond to the question, “Do you read with your child now? (See Table 4a). This is a significant question because many of the other questions are phrased to collect data from both the past and the present. The phrasing of this question also allows for reading activities other than just parent read aloud.| Table 4a. Involvement: Currently Reading with Child |

| | Grade Level | Yes | No | | Third Grade | 14 | 2 - R | 3 | 0 – R | | 5 – Y | 0 – Y | | 7 - G | 3 – G | | Fourth Grade | 8 | 0 - R | 4 | 0 – R | | 2 – Y | 0 – Y | | 6 - G | 4 – G | | Fifth Grade | 10 | 5 - R | 6 | 2 – R | | 2 – Y | 1 – Y | | 3 - G | 3 – G | | Total | 32(71%) | 7 - R | 13(29%) | 2 – R | | 9 – Y | 1 – Y | | 16 - G | 10 - G |

|

|

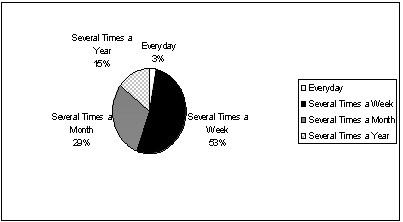

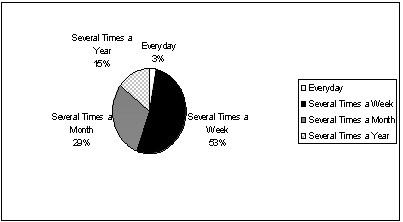

Of the responses given, 76.9% of the students who are not currently reading with their parent (family member) are performing at grade level, compared with 50% of the students who are currently reading with a parent (family member). Interestingly, this does not seem to match the assumption that student achievement is impacted by parental involvement in the form of reading activities. This might be further explained, however, by the responses to Survey Question 8 which asks, “If you answered yes to Question 7 (you are currently reading with your child), how often do you read with your child? (See Graph 4a). | Graph 4a. Involvement: How Often Parent/Child Read Together |

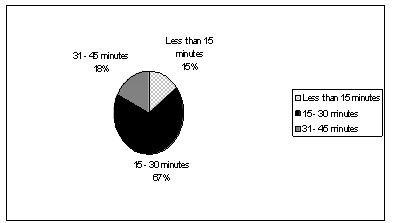

Of those that said yes, they are currently reading with their child, only 53% are reading on a consistent (daily) basis with their child. The next question, Survey Question 9 further explores this by asking, “If you answered yes to Question 7 (you are currently reading with your child), when you read with your child, what is the average length of time you read together?” (See Graph 4b). | Graph 4b. InvolvementLength of Session When Parent/Child Read |

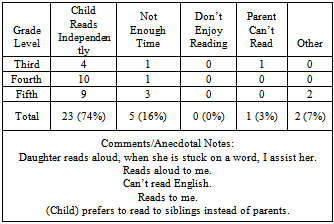

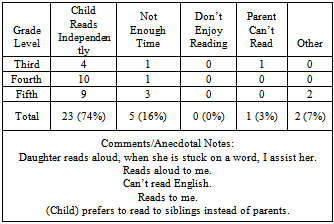

When parents (family members) do read with their child, the majority read for a reasonable amount of time to have an impact on student achievement.If participants responded ‘No’ to Survey Question 7, “Do you read with your child now?”, the participant was then asked to skip to Survey Question 10 which asks, “If you have never read with your child or only read with your child several times a month or a year, why is that?” (See Table 4b).Data seems to demonstrate that parental involvement in reading ceases when a child learns to read independently. In addition to Survey Question 10, there was a second question, “If you don’t enjoy reading or know how to read, would you choose to read more with your child if reading wasn’t such a struggle?”, that was not numbered to which four participants responded yes. Table 4b. Involvement: Reason for Not Reading with Child

|

| |

|

Survey Question 19 asks participants how often they took their child on outings such as museums, parks, sporting events, stores, movies, plays, relative’s or friend’s houses. The majority of the responses, 57.78%, indicated that outings were taken one or more times a week, with approximately 25% stating they took outings monthly. The written comments implied that it was difficult to choose any one category to represent a true average, because during the summer more outings were taken than during the school year.

4.5. Miscellaneous

Several questions did not specifically fit into one of the categories identified as having meaningful impact on improving student achievement, but yielded notable data.Survey Question 21 asked if participants taking the survey would be willing to participate in a four-week family literacy program called Building Bridges to Literacy (See Table 5a).| Table 5a. Miscellaneous: Participation in Building Bridges to Literacy Program |

| | Grade Level | Yes | No | NoResponse | | Third Grade | 6 | 11 | 0 | | Fourth Grade | 5 | 6 | 1 | | Fifth Grade | 6 | 9 | 1 | | Total | 17 (37.38%) | 26 (57.78%) | 2(4.44%) |

|

|

Of the 17 that said yes, only 10 (58.82%) would make the commitment to attend the program for all four evenings. The primary reason given for non-willingness to participate, or inability to attend all four evenings, is work related issues. This information changed the focus of this investigation. From here the focus turned toward looking primarily at the information as perceptions and involvement of families in regards to reading and student progress. Survey Question 5 asks, “Circle the statement(s) that best describe the reading behavior between you and your child. (Please circle all that apply.)” The majority of the responses indicate that a parent or a family member has read to the child from birth. Eighteen percent circled the response that states they have stopped reading to their child. Thepredominant age noted is eight which translates to somewhere between second and third grade when a child should be reading independently. Eighty percent (36) of the participants indicated that they read to their child in English. Eleven indicated that they read in Spanish, seven in other languages. Many of the participants that choose English included the other languages in addition to marking English. There were two that added a comment which stated they spoke no English at all. Survey Question 14 asks, “Which reading activities have you, or do you, currently engage in? (Please circle all that apply.)” (See Table 5b)| Table 5b. Miscellaneous: Reading Activities Families Engage In |

| | Reading Activities | Third | Fourth | Fifth | Total | | Read picture book – look at pictures. | 5 | 5 | 4 | 14 | | Point to words while reading. | 2 | 4 | 4 | 10 | | Repeated Readings | 1 | 3 | 3 | 7 | | Discuss new words. | 4 | 5 | 5 | 14 | | Child creates/retells story from pictures. | 3 | 2 | 5 | 10 | | Variety of books read. | 5 | 7 | 5 | 17 | | Read rhythmic stories. | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | | I read a page, you read a page. | 5 | 2 | 3 | 10 | | Silently read while listening to CD. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | | Discuss story or make connections. | 4 | 2 | 5 | 11 | | Discuss story by making predictions. | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 | | Child reads,parent/familylistens. | 15 | 9 | 16 | 40 |

|

|

Predominant reading activity at this age level appears to be the child reads while a parent or family member listens. This reading activity is considered passive in nature for both child and parent.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings

Questions three and four explore the substantial decline in the intermediate grades of daily reading. The correlation between those daily reading habits, students’ achievement and family involvement are also explored prompting the question, “Can the drop in daily reading habits and student achievement be averted though family interventions?” A subsequent question that emerged throughout the study was, ‘Does the type of intervention impact a family’s willingness to become involved?”Responses from the participants seemed to indicate that family reading activities changed, or were discontinued, when children reached the age of eight which is roughly between second and third grade. So according to the study, there is a correlation between reading habits and family involvement. Although the correlation exists, there are many other factors to consider when examining the data. Literature cited earlier leads us to conclude that the dramatic drop can be positively altered, if family involvement is not discontinued or if the literacy activities are modified to match their child’s development.The number of initial Questionnaires for Parents (surveys) returned was fairly evenly represented in each of the grade levels. However, the disproportionate number of Green/Tier 1 responses returned means that Yellow/Tier 2 and the Red/Tier 3 families’ data is not accurately represented. Since these reading tiers contain students who are performing below grade level, their data is critical to understanding how family involvement can impact student achievement. The school’s actual Free and Reduced Lunch Program population is also underrepresented in the survey responses by approximately 9%. The household income is compared to reading achievement levels. The most notable result is the number of students performing at grade level in the low-income range. One possible explanation is that, these are the children of parents who value reading achievement, because they chose to complete the survey. Since the data showed that struggling readers, as well as low-income students/families, were under represented, their data cannot be included for a more valid and reliable sampling.Several questions take into consideration factors related to the home environment. One critical component in the home environment is the availability of printed materials. The availability of printed materials in the home is one key indicator of the family’s values with regard to literacy. Low-income families can still meet this criterion by taking trips to the public library. The data (Table 2) indicates that there is a strong correlation between availability of printed material and reading achievement. Eighty percent of the respondents had printed material readily available in the home, with 58% of those achieving at grade level and 28% showing some risk. A substantial number of participants rated themselves as “Usually Talkative” with their child. (Graph 2) According to Hart and Risley[7] the increased conversation should translate to a higher listening vocabulary which translates to a higher reading and expressive vocabulary as well. This can be offset by the fact that when students reach the intermediate grades their vocabulary begins to become more content based.Expectations are measured on the survey in two main areas, letter grades and the ratio of praises to critiques. Grade level expectations, while more overt, are a less consistent form of relaying expectations. Focus on grades tends to reinforce school time reading, which does not ultimately reinforce the value of becoming a lifelong reader. Graph 3 shows the level of parent perceived praises to critiques which is a much more subtle, yet consistent, form of expressing expectations. Although parents felt they praised their child on a daily basis two times more that critiquing them, over the long-term, a 1:1 ratio became apparent. Since the optimal ratio is 4:1[9] and the school’s actual reading achievement scores are lower than normal standardized scores, the lower scores reflected in the data collected could be accounted for by the fact that over the long term – consistent parent expectations are low.Parents’ involvement at home, school and in the community is also believed to be one key indicator of student achievement in reading. So, choosing to not only be involved in the family literacy program, but making a commitment to attend all four evenings, is a key component of family involvement. Based on the comments written providing reasons for not being able to attend, factors beyond the family’s control were involved. Once again this reinforces the fact that teachers and schools need to think out of the box for solutions to actively involve families in literacy if they want to form partnerships that are not deficit-driven. From the data collected, it is also problematic that parents stop consistently engaging in explicit literacy activities by third grade. Instead, other forms of literacy activities that are more grade level appropriate should replace the traditional read aloud when a child learns to read independently. Literacy interaction is still necessary to develop the critical thinking skills needed for literacy achievement. As the old saying goes, “Actions speak louder than words.” Most troubling was data placed in theMiscellaneous section discusses the reading activities in which parents and children are engaged. The highest response of “the child reads and the parent listens,” signifies that both children and parents are passively participating in literacy. Active participation is necessary to move struggling students closer to grade level performance[16].

5.2. Limitations of Study Procedural Limitations

This is a study of convenience which only includes data from one elementary school in a collar county of Chicago, Illinois during one school year. Encompassing intermediate grades levels (third, fourth and fifth grade) , this study did not include a comparison between the primary and the intermediate grades to further document the drop in daily reading habits, change in attitudes towards reading and parental involvement and modelingbehaviors. Oral Reading Fluency is the only method used to measure student impact, and did not include a reading interest survey completed by the students. Because direct observation is not possible, the study is dependent on the perceptions of the respondents answering survey questions.

6. Summary and Recommendations

Several recommendations should be considered for future research. First, personally contacting families of struggling readers and/or low-income families may have induced more of them to participate in the study. Including home visits with anecdotal observations would have also provided the researcher with a more complete and accurate picture of family involvement. A follow up question should have been included on the survey to determine if the printed materials were at their child’s independent reading level and/or used regularly. Adding a question about parental expectations for college could have also provided insight related to parental expectations. The study focused more on deficit-driven activities and ideology, and could be changed to incorporate more non-traditional methods of literacy activities such as inquiring about the use of e-books and other digital technology to read and write.Finally, it would have been helpful to know how literacy is modeled in the home: Do parents read? How often? What do they read? Teachers should be encouraged to discuss the importance of parental involvement during open houses and conferences.From the data collected, two factors that impact student achievement became clear. First, parental values and attitudes towards reading are closely correlated to achievement, provided these values and attitudes are expressed through action and not just empty words. Second, demographics (socio-economic status, race, culture, etc.) do not necessarily accurately represent values and attitudes towards reading. Teachers and schools should not prejudge based on demographics. It is also striking, and should be noted, how much teachers and schools operate under a deficit-driven ideology. To eliminate stagnant levels of reading, the ideology barriers must be broken down, so true partnerships can emerge.“If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be”[12]. Schools need to create lifetime readers, not produce aliterate school time readers. Lifetime readers are also lifetime learners who seek to gain knowledge and understanding which becomes our nation’s ultimate weapon to preserve freedom and democracy while destroying ignorance, poverty and despair[20]. Creating lifelong readers is a weapon worth building in our schools - for future generations, preserving freedom and democracy while destroying ignorance, poverty and despair, is a war worth fighting with strong alliances in place.

References

| [1] | 107th United States Congress. (2001). Public Law 107-110: No child left behind act of 2001. Retrieved February 26, 2007 from http://www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02/index.html. |

| [2] | Cooter, K.S. (2006) When mama can’t read: counteracting intergenerational illiteracy. The Reading Teacher. Volume. 59. No. 7. April 2006. |

| [3] | Creswell, J.W. (2003). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches: second edition. Sage Publications. |

| [4] | Foertsch, M. (1992). Reading in and out of school. Educational Testing Service/Education Information Office: U.S. Department of Education. (pp.6-7, 35-36). |

| [5] | Gunning, T.G. (2005). Creating literacy instruction for all students: Fifth edition. Pearson Education, Inc. |

| [6] | Gallagher, K. (2009) Readicide: how school are killing reading and what you can do about it. Stenhouse Publishers. (pp. 1-5). |

| [7] | Hart, B. &Risley, T. (1996) Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Brookes Publishing. |

| [8] | Henderson, A.T. &Berla, N. (1994). A new generation of evidence: the family is critical to student achievement. Center for Law and Education. Washington, D.C. |

| [9] | Huitt, W. & Hummel, J. (2006). An overview of the behavioral perspective. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA. Retrieved September 20, 2009 from http://chiron.valdosta.edu/whuitt/col/behsys/behsys.html. |

| [10] | Illinois State Board of Education. (2009). Illinois school report card. Retrieved February 26, 2009 from http://www.isbe.state.il.us. |

| [11] | Jefferson, T. (1814). Letter to Peter Carr, 1814. Retrieved July 15, 2009 fromhttp://www.geocities.com/Athens/6529/notebook/jefferson_quotes.html?200915. |

| [12] | Jefferson, T. (1816). Letter to Colonel Charles Yancey, January 6, 1816. Retrieved July 15, 2009 from http://www.geocities.com/Athens/6529/notebook/jefferson_quotes.html?200915 |

| [13] | Kerbow, D. (1999). Critical issue: addressing the literacy needs of the emergent and early readers. Retrieved July 6, 2009 fromhttp://www.ncrel.org/sdrs/areas/issues/content/cntareas/reading/li100.htm. |

| [14] | Leedy, P.D. &Ormrod, J.E. (2005). Practical research, planning and design: eighth edition. Pearson Education, Inc. |

| [15] | Mays, L. (2008). The cultural divide of discourse: understanding how English-language learners’ primary discourse influences acquisition of literacy. The Reading Teacher. Voumel. 61. No. 5. February 2008. (pp. 415-418). |

| [16] | National Endowment for the Arts. (2004). Reading at risk: a survey of literary reading in America. Retrieved June 30, 2009from:http://www.nea.gov/news/news04/readingatrisk.html. |

| [17] | Padak, N. &Rasinski, T. (2007). Is being wild about harry enough? encouraging independent reading at home. The Reading Teacher. Volume. 61. No. 4. December 2007/January 2008. (pp. 350-353). |

| [18] | Purcell-Gates, V. (2000). Family literacy. Handbook of reading research, Volume III. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. (pp. 853-870). |

| [19] | Risko, V.J. & Walker-Dalhouse, D. (2009). Parents and teachers: talking with or past one another – or not talking at all? The Reading Teacher. Volume. 62. No. 5. February 2009. (pp. 442-444). |

| [20] | Trelease, J. (2001). The read-aloud handbook, fifth edition. Penguin Books. |

| [21] | vanPeeren, T. (1999). Critical issue: addressing the literacy needs of the emergent and early readers. Retrieved July 6, 2009 fromhttp://www.ncrel.org/sdrs/areas/issues/content/cntareas/reading/li100.htm. |

| [22] | Waldbart, A., Meyers, B & Meyers, J. (2006). Invitations to families in an early literacy support program. The Reading Teacher. Volume. 59, No. 8. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML