Yael Fisher

Graduate School of Educational Administration, Achva Academic College, 79800, Israel

Correspondence to: Yael Fisher , Graduate School of Educational Administration, Achva Academic College, 79800, Israel.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to analyze excellent schools and learn from the quality processes implemented in these schools. This article presents the success stories of two high schools in Israel and identifies the determinants/s that have led each school to being recognized as excellent. The study indicates that while there is no single theoretical model that characterizes excellent schools, there are certain factors that facilitate the adoption of an organizational culture of excellence, which can pave the way to success. The article presents an original empirical study which was based upon success stories that enabled to characterize excellent schools.

Keywords:

Qualityschools, Leadership, Excellence, Success Stories, School Organizations

1. Introduction

1.1. Excellent Schools –Terminology and Definitions

One of the most notable characteristics of excellent schools is the existence of a clearly established underlying mission, which motivates all of the school’s activities and decisions. The mission is grounded in the pursuit of academic excellence, adapting to students’ needs in terms of their cognitive development, and promoting social equality[1]. In regard to academic achievements in excellent schools, the curriculum, the teaching and the evaluation are all performed at the highest standards and each student is expected to meet the required standards. Self-evaluation processes are also employed[2]. It has been shown that schools defined as excellent allow the members of their teaching faculties to plan, choose and participate in their own and in the students’ professional development. Teachers are given ample opportunity to collaborate with colleagues, expand their professional knowledge and improve their teaching skills. In addition, they partake in decision making on matters pertaining to the curriculum and to teaching methodologies

1.2. The Role and Position of the School Principal

Most of the recent studies on the role of the principalindicate that the main function of the school principal is to provide the educational and pedagogical leadership that can improve the educational and learning experience of the entire student population. Research demonstrates the significant role of the principal in improving the quality of teaching and its outcomes, as gauged by students’ academic achievements[3],[4]. Some scholars consider the principal’s role to be the central and most important factor in obtaining such results. Consequently, the last decade has seen the creation of a new role for the school principal, namely, that of instructional leader[5]. The underlying assumption is that by devoting time to train their teams on issues of instructional responsibilities, principals practice effective educational leadership, as their efforts have a direct effect on students’ academic accomplishments[6],[7]. While the traditional role of the principal includes managing the school’s everyday functioning, the leadership role emphasizes aspects such as innovation, values, ethics, inspiration, goal setting, and especially the ability to motivate a group of people to work together towards an established common objective. Viewing the principal in a leadership role makes it possible to adopt approaches from the realm of business management. Thus, it has been proposed that school principals who match Collins’ Level 5 leadership[8] are capable of forging a path that will lead their schools towards completing the previously described tasks[9].

2. Methodology

First and foremost, this is a qualitative study, based on learning from success approach. It advocates seeking out examples of success and learning from them in a manner that transforms personal knowledge and know-how into actionable knowledge, which can be implemented by organizations and teams[10]. The aim of this research was not to address a problem, but rather to try and answer two main questions: what is a high-performance school? And what does a principal do to create a high-performance school? The current study employs this approach and presents a retrospective survey of two success cases. The presentation of these success stories does not utilize the principles of grounded theory, despite the fact that it would have enabled the creation of a model based on the data collected and interpreted[11]. Nevertheless, stories of past success can be a useful tool, as they provide schools with a framework from which to consider their own activities, while affording them the freedom to adopt partially or entirely the lessons learnt, examine their suitability to their own circumstances, and then act in accordance with the conclusions drawn.

2.1. The Sample

The investigation originally encompassed the success stories of five different schools, but it was decided to review only two for the purposes of the current article. The two schools that were chosen represent the two major educational sectors in the State of Israel: The secular and the religious. The two schools reviewed herein are the Regional Rural High School (School A), located in southern Israel and the Religious Girls’ High School (School B), located in central Israel. At the first stage, the author contacted Education Ministry’s regional supervisors and requested a list of schools they considered excellent. In addition to the request for recommendations, the author contacted schools that already had an established reputation of excellence.All of the recommended and reputable schools could have been worthy of inclusion in the study; thus, the final decision regarding inclusion was based on the individual principals’ willingness to cooperate with the author of the study. Another criterion was the ability to create a sample representative of a variety of sectors. Based on these factors, five schools were selected for the study. As mentioned, the current study presents the success stories of only two of these schools. Given the agreeable nature of a success story, the real names of the schools and the principals are presented, in recognition of their achievements.

2.2. Research Instruments

Although this is chiefly a qualitative study, it also combines several quantitative components. The qualitative part utilized a variety of research instruments: partially structured in-depth interviews with the principals and others in senior positions; student and teacher focus groups; content analysis of documents, particularly the school's correspondence with parents and students; observation of school meetings involving leadership teams; observation of parent-teacher meetings; collected written materials about the schools and their approaches vis-à-vis the parents’ role.One useful resource was the officially reported outcomes of nation-wide students’ tests, which are conducted among all primary, middle and secondary schools, in the following subjects: sciences, native language skills in Hebrew or Arabic, math, and English language proficiency. This source provided important data regarding academic achievements and school climate in elementary and junior-high schools. The study reviewed the outcomes of tests conducted during the 2005 school year. Additional data for the study were collected using two questionnaires: (i) Staff Mapping Questionnaire and (ii) Parents and School: Attitudes and Parental Involvement.The staff mapping questionnaire was devised for research purposes and is based on previous studies[12],[13],[14]. It aims to examine the approaches of members of the pedagogical staff on five topics related to performance: goals, delegation of responsibilities and functional flexibility, relationships among staff members, productivity (level of school’s output), and recognition and awareness.An initial review of the staff functioning scale found a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of .94 for the items. Calculating the average score for all of the scale’s components rendered a sense of the staff’s general perception of its functioning. "Parents and School: Attitudes and Parental Involvement" scale, developed by Fisher & Friedman[15], was used; it includes four sub-scales: degree of parents’ identification with the school’s mission and vision; degree of parents’ awareness; school’s demonstration of trust in students and parents; degree of parents’ actual involvement. Internal consistencies for the scale were as follows: .89 Cronbach’s alpha for all of the items; .88 Cronbach’s alpha for the identification sub-scale; .84 for the awareness sub-scale; and .70 Cronbach’s alpha for the trust sub-scale.

2.3. Research Procedure

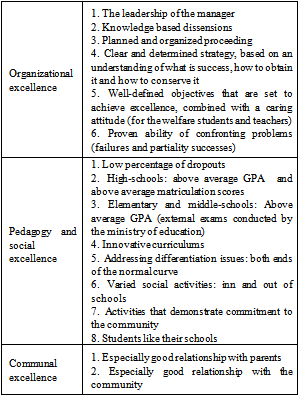

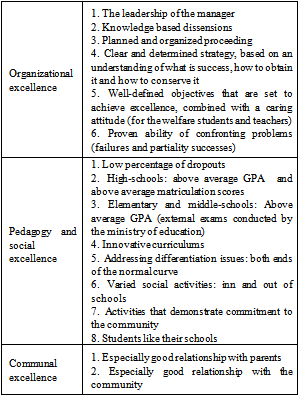

Table 1. profile of excellent schools

|

| |

|

The research was conducted between the years 2005 and 2006. The first stage was to establish a steering committee, which was headed by the former Chief Manager of the Ministry of Education, and included principals, professionals in academe, and representatives of the funding organization of the research. Table 1 presents the characteristics of excellence selected by the steering committee.

2.4. Structure of the Success Story Description

For the most part, identical topics are reviewed in each success story. Nonetheless, given that certain characteristics exist in one school but not in the other, there are some differences. Thus, for example, in the success story of School A, the subject of strategy renewal and organizational culture is followed by that of organizational structure, whereas the in the success story of School B, the parallel content unit looks at organizational structure and annual pedagogical program, which includes the subject of strategy and organizational culture. Similarly, the School B story contains a section on the school’s budget, with no parallel section in the story A, since the latter school receives its budget from state and local authorities. The story of school B also includes a section on managing diversity, whereas in that of school A, this topic is not addressed in a separate section.

3. Results

3.1. Success Story of School A - A High School in Southern Israel

The number of students enrolled at this school at the time of the study was 750; 130 were living on campus in the boarding school; 25 were Arab minority students. Students were referred to by the school staff as trainees or learners, terms that correspond to the school’s mission statement. The school is not selective, and all classes featured a mix of students from various population sectors; in each grade level there was a small class for special needs/education students, who constituted 10% of the entire student body.

3.1.1. Organizational Excellence

The first characteristic of organizational excellence was the principal's leadership. The principal demonstrated the key qualities that correspond to Collins’ Level 5 leadership, namely, a “paradoxical mix of personal humility and professional will”[8]. Collins’ Level 5 leaders are humble, reserved, quiet, and even shy, while simultaneously displaying professional determination and enthusiasm along with a strong will to attain their goals. These traits were apparent upon meeting the principal. During our first meeting, when he described the school’s activities, he used the pronoun we rather than I. Polite and somewhat shy, he became serious and determined as he discussed the school. We asked “what is an excellent organization?” and he replied: “an organization that does today what couldn’t be done yesterday and will do tomorrow what cannot be done today.”In the eight years that he has held the position of principal, the school underwent a significant change, from being a kibbutz-style educational institution of yesteryear, characterized by a distancing from formalities, open and flexible attitudes, and an affable atmosphere, to a school where boundaries are clear to students, teachers and parents alike. The first step was to establish unambiguous roles. The principal also initiated well-defined and -organized decision making processes that left no room for personal interpretation.In response to the question “who did he believe was responsible for the school’s success?” he replied: "It doesn’t matter to me that when I no longer work here, the teachers will say ‘we succeeded’." He believes in negotiating with the teachers and refrains from imposing his opinions on those who do not agree with him. At the time of the interview, there were 32-34 students in each class, while the stated goal was to limit the number of students per class to 32 at the most. The principal explained that he would like to initiate a change in the class configuration: he was very displeased with the fact that the school had not yet succeeded in breaking away from the traditional formation of board-teacher-rows of students.The teaching staff, parents and students considered the principal to be a leader who attributes the school’s success to the staff, while taking full responsibility for any failures. His main management approach was to delegate.The secondcharacteristic of organizational excellence was the strategic planning and organizational culture.Having understood that the strategic plan needed to be reassessed, the school underwent three major processes between 1998-2006, the aim of which was to re-examine and rebuild the organizational strategy of the school. Occasionally the assistance of an external consultant was sought in the overall process. The entire staff was involved in the planning of multi-year educational programs: in line with the new strategy, these included also new organizational aspects, such as deadlines, routine staff meetings, structured workflow programs, and strict implementation of decisions.The first stage began in 1998, the principal's first year as principal: a new school vision was defined, and the need for delegating responsibilities through additional authority figures was recognized. Goals were set with staff consensus, a work plan with a corresponding schedule was designed, and the staff was divided into action groups and each was assigned a unique task.The second strategic process, which began in 2003, was initiated in response to a decline in registration, and the local authority’s refusal to unconditionally underwrite the school. Before embarking on this process, a survey was conducted to assess parents’ attitudes towards the school. According to findings, parents noted the school’s willingness to assist students with difficulties – no matter what this required, and that the school made every effort to prevent students from dropping out. Additionally, findings indicated that academic achievements and matriculation grades were above the national average, with noticeably high grades in the humanities. Parents, as well as students, expressed their support for the school, in general, and a high degree of satisfaction with the school’s social activities, in particular. Based on these findings, it was decided that the strategic process would focus on aspects of marketing, with the specific purpose of attracting students from neighboring jurisdictions, and efforts would be made to increase the school’s interactions with parents from these neighboring regions and with the population in general.During the period of change, which was allotted two years, the staff –for the most part– supported the principal. The major changes that ensued might have seemed superficial, such as cancelling communal breakfasts and snack time in the school cafeteria, adding window grates and building a fence around the school grounds. However, the significance of these actions ran deep, as they went against past conventions and indicated, in the words of J.B., “embarking on a journey in a new direction.” Thus, for example, the fence was added to define the school grounds and create clear boundaries for students. Although the students’ sense of freedom was compromised, their attitude towards the school remained essentially unchanged.The third strategic process, which began in 2006, was dubbed Determined Involvement. The principal initiated this project, inspired by the theories of Omer[12] for managing behaviors involving risk, violence and destruction, among children and youths. According to this approach, acts of violence must be met with resolute opposition, while simultaneously working to avoid polarization between the youth who use violence and the adults who oppose it. The thirdcharacteristic of organizational excellence was the organizational structure.At the time of the study, the school’s organizational structure was clear to the entire staff and to the student body, meaning that all of the community’s participants understood their roles and what was expected of them, which resulted in organized and streamlined management. This understanding was reflected in one of the school’s key phrases: “do the right thing: not just to avoid wrongdoing, not out of fear of punitive reactions or a desire for appreciation and gain; do it because you understand that it’s the right thing to do.” Of the school’s 76 teachers, 40 held a position with managerial responsibilities. The school management included the principal, the vice-principal, the middle school principal, the pedagogical coordinator, the school treasurer, the scheduling coordinator and the boarding school manager.The teachers appeared to recognize a clear, role-based organizational structure, which enabled them to solve problems more efficiently. As one of the teachers said: “things are organized and we know who to turn to if there’s a problem.” Thus, a disciplinary issue with a student would be handled by the homeroom teacher; only rarely would such an issue be brought to the principal. Of course, it was possible to bring personal problems directly to the attention of the principal and would be addressed seriously and respectfully.The school was funded by the Ministry of Education, the local authority, and through mandatory fees paid by the parents.The fourth characteristic of organizational excellence was the staff’s sense of functional capacity. To assess the teachers’ attitudes regarding the staff’s functioning, the Staff Mapping Questionnaire was used (see 2.2). The majority (60%) of the pedagogical staff of School A perceived the staff as functioning at a high level, a finding based on the joint assessment of all of the questionnaire’s components. A summary of the findings is presented in Table 2.In addition to filling out the questionnaire, members of the pedagogical staff were asked similar questions in a personal interview. Findings from the anonymous closed-question written responses were found to match those obtained from the interviews, which suggests that staff members were comfortable expressing their feelings and responses.| Table 2. The pedagogical staff members' feelings about the functioning of of School A |

| | | Percentage the staff of teachers who feel that the staff functions in a very high level | Percentage of teachers who feel that the staff functions in a very low level | | General Function | 60% | 5% | | Targets | 72% | 2% | | Delegation of authority | 52% | 5% | | Flexible roles | 52% | 7% | | Relationship and communication within the staff | 60% | 7% | | Productivity (operational productivity | 50% | 5% | | Recognition and appreciation | 76% | 2% |

|

|

Furthermore, 72% of the pedagogical staff demonstrated substantial familiarity with the school’s goals, although not all teachers understood the difference between goals and objectives.Most of the teachers defined the school’s main goal as educating students to graduate and contribute to society: “to educate them not only as students but as human beings,” “to help form individuals who contribute to and are aware of others and their needs,” “to promote social activism and an understanding of values,” “to raise thinking, inquisitive, moral individuals, who contribute to themselves and to society – in short, human beings!” “to inculcate social values … to turn them into responsible adults.” This finding is particularly significant, as it indeed echoes the school’s mission statement. Many teachers also noted that developing “students’ aptitudes” was one of the school’s important goals. Some of them provided a broad definition of this goal, e.g., “the ability to follow rules” and “increasing students’ aptitudes,” while others mentioned some of its components, e.g., “helping students acquire good study skills,” “creating study habits,” and “providing tools to enable independent learning.”

3.1.2. Pedagogical Excellence

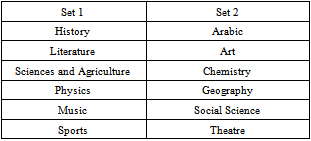

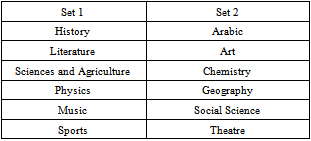

The first characteristic of pedagogical excellence was thehigh level of student retention. This school does not select from a pool of candidates, but rather is committed to accepting all those interested in attending. Given that this is a regional school, students who live in areas that are not included in a municipal union agreement are required to pay tuition higher than that paid by local students. The school does not expel students and the dropout rate was very low; in fact these instances were usually related to a family’s move or the student’s independent decision.The second characteristic of pedagogical excellence was academic achievements. While the school’s retention rate is high and the dropout rate low (lower than 1%) and the school strictly advocates the pursuit of a competitive matriculation certificate, it is equally intent on providing options for special education/needs students. There are 6 special education classes at the school, with 6-14 students in each.Almost all students chose two extra credit electives based on their interests. The school is insistent that students not be expelled from an elective due to poor achievements, but only due to poor functioning. The pedagogical coordinator explained: “the electives open the door to a new area of knowledge, not to a future profession. If you’re interested in learning more about the subject, then by all means choose it, but be sure that it suits you, that you are equipped to handle the subject matter.”Over the recent years there has been a notable change in the students’ approach to extra credit electives: their choices are more achievement oriented. Many wish to succeed and obtain high grades; they see it as a window of opportunity as they face the future. Many students now want to obtain a broad based, competitive and impressive matriculation certificate.Homeroom and subject teachers, grade coordinators and the school’s leadership team are all concerned with ways to increase the level of achievements, the yearly grade point averages and the matriculation marks. Grade point averages are recorded from 7th grade and on. In 1998, 75% of students qualified for a full matriculation certificate, compared to 80% in 2001; quite a leap in 3 years. Similarly, there is almost no gap between students’ yearly grade point averages and their matriculation averages. The third characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the curriculum. To ensure that students obtain a valuable matriculation certificate, the school follows a rigorous program. Between the 10th and the 12th grade, students study two extra credit electives, which they chose in 9th grade. Their decision process comes on the heels of a special educational process in which the educational team (grade coordinator and homeroom teacher), the school counselor, the student and the parents are all involved. Switching electives is permitted only during the first month of the 10th grade. These electives are typically worth 5 credits on the matriculation certificate (English and math classes of five credits are not considered “electives,” but rather “expanded credit subjects”). The electives are organized into two lists, and all of the subjects in a single list are taught during the same time slot (see Table 3). Consequently, students must choose one elective from each list.Table 3. School A - electives subjects by two sets of "baskets"

|

| |

|

The fourthcharacteristic of pedagogical excellence was the quality of life at school. Until 2006, quality of life at school pertained only to students’ lives; however, since teachers’ behaviors also affect the quality of life at school, it was decided in 2006 to reformulate the ethics code, as part of the Determined Involvement approach. Nowadays, the code is presented in a “school regulations handbook;” it pertains to the entire school community, the staff and the students, and provides the guidelines for the school’s functioning. This published document of school regulations is divided into four sections: practices and procedures (regulations of do’s and don’ts); teachers’ functions (defining limits); students’ functions (relates to students’ obligations); and academic regulations. Most of the document was written by the school’s management and teachers, although on some articles, parents and students were consulted.The school set a very low threshold for violence. Daily life at school was conducted using the “safe schools” model (a program developed by the police department’s division of community and civil watch to prevent violence among children and youths). Teachers reported that in addition to the clearly defined do’s and don’ts, they too participated in the efforts to define and maintain limits. However, they were not alone: 8th and 9th grade students decided to participate in the “peace creator” program, which had been functioning at the school since 2002. The school was not completely drug-free, but it addressed the problem not only within the school’s confines and schedules, but also beyond the school grounds and during extracurricular activities. Although the school is not legally responsible for the students after school hours, as educators, the school staff considered itself morally responsible for the students’ welfare at any time and place. While it was difficult to quantify the use of drugs around school, according to data that had been gathered by the school, it appeared that the degree of use had decreased.The school was also very aware of problems related to sexual behaviors and the relevant limits. Information of improprieties was most often received through the trusting relationships between students and their teachers, school counselors or boarding school mentors. Whenever improper behavior is reported, the civil patrol officer is consulted, since the person in this role is considered to have the experience necessary to conduct a comparative assessment of the events. The school has also collaborated with the juvenile division of the police, located in the nearby town. The problem of alcohol consumption was also on the school’s agenda, and several steps were being taken in an effort to dissuade students from drinking. Following several reports of school parties where alcohol was consumed, the school formulated a “behavioral code,” which parents were required to sign in the presence of the students, so as to take responsibility for the child’s behavior. A student whose parents would not sign would not be permitted to attend school parties.The school staff had been alerted to the problem of destruction of public property. However, approximately two years beforehand this issue had been resolved by shifting the responsibility to the students. Each class was allotted a budget for materials, which could either be used for purchasing new items or for replacing those that had been damaged. The result was a significant decline in the number of incidents. The fifth characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the school’s pedagogical staff. There were 76 teachers on the staff at School A; 79% of them were women, a rate which is slightly above the national average (70%). A review of the data suggests that the profile of teachers at this school is no different from that found at a typical Israeli high school, with one exception: more than 65% of the teachers (50) at the school worked there in full time capacity. Approximately half of the staff had a Bachelor’s degree (51%), more than a third a Master’s degree (39%), and 3% (2 teachers) held Ph.D. degrees. Of the entire staff of 76 teachers, 19 were younger than 40 years of age and 4 were younger than 30 years of age (similar to the national averages). The majority of the male teachers were more than 45 years old, and there was a match between age and seniority, indicating that most of the older staff members were also veteran teachers who had been teaching under the Ministry of Education for more than 15 years. This was particularly useful for the purposes of this study: since most of the veteran teachers had been at this school for their entire career, they could attest to the changes it had undergone.The sixth characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the professional development of the staff. Each new teacher is accompanied by a veteran teacher and by the coordinator of the relevant subject. The pedagogical coordinator oversees this process and holds meetings with the new teacher twice a year. During the course of the year, two training meetings are held also with the principal.Professional development for teachers was an integral part of the school’s organizational culture, and workshops were held several times a year, based on the school’s needs or the relevance of the topic. The selection of topics has shifted over the years, from more general, “feel good” sessions to more practical, pedagogically oriented learning. In addition to selecting and providing workshops, the school also encouraged teachers to pursue degrees in higher education, and even offered tuition assistance.The seventh characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the teaching staff’s definition of excellence. Interviews were conducted with veteran teachers in order to understand their perspectives and their characterization of the changes that the school had undergone. The interviews were held one–on-one; all teachers noted that excellence is not limited to academic achievements. They drew a distinction between excellent achievements and striving for excellence; regardless, they preferred to speak in terms of student aptitudes. Thus, for them, excellence meant that students should be able to realize their full human potential. Of the many explanations provided when describing what is meant by “student excellence”, a few merit special mention: “students who identify and face challenges demonstrate excellence,” “students who face the future with remarkable motivation,” “students who feel a sense of responsibility towards their peers,” “students who are prepared and eager to work hard, who demonstrate interest and curiosity,” “students who are prepared to learn and to share, who demonstrate involvement in school and also beyond it, in society, and at the same time are not quick to yield to pressure, from peers or others.”According to the interviews, excellent teachers are respected and appreciated by all. There was an agreement among interviewees that excellent teachers consider themselves an integral part of the educational staff, are prepared to contribute to the staff, and are constantly engaged in a process of self-assessment. Two expressions that are representative of the teachers’ definitions are: “excellent teachers are those who succeed in arousing students to interact with the subject matter, who manage to convey their love for the subjects they teach, and who succeed in communicating both the fascination and the significance of the subject matter.” and The second representative statement was: “to be an excellent teacher means to love the students.” Interestingly, all of the interviewees described themselves as still aspiring to excellence. They were careful not to qualify themselves as excellent, as one of the teachers put it: “I’m afraid I’d demand less of myself; I want to keep improving.” As was mentioned regarding level 5 leaders, the same sense of humility was noticed among the teachers. Although the students consider them to be excellent teachers, the teachers themselves refrain from doing so.An excellent school, in the interviewees’ opinion, is one in which feedback is an integral part of the organizational culture. They claimed that a school’s excellence is well represented when “the quality matches the investment.” The teachers were asked to provide a metaphor that represents their school’s excellence. Some described it as a “nature reserve, a rural campus that preserves the relationships between the teachers and the students as well as within each group,” while others saw it simply as “a workplace.”All of the teachers at School A agreed that an excellent school addresses the needs of all of the students within a normal curve; indeed, School A includes a region- wide class that accommodates the special education needs of a small group of students. These classes are referred to as “small classes.”The principal believes that excellent teachers give an added value to the subjects they teach, awaken students’ curiosity about and love for the subject, connect the subject to other fields and expand students’ knowledge. However, he does not rely solely on his own definition, but rather conducts yearly interviews with a cross-section of high school seniors to inquire about the kind of teachers they would like to remember. Some of the students’ responses were “the ones who were there for us when we needed them,” “attentive and compassionate,” with broad horizons, fascinating, unconventional,” “they see us as individuals and care about us,” “they stand head and shoulders above the crowd,” and “the homeroom teachers are the school’s backbone.”

3.1.3. Social Excellence

School A considers its focus to be on social-educational values. This is expressed in its mission statement: “Our school is grounded in the humanistic approach, which fosters respectful dialog among all of its community members, and centers on the student as a complete and multifaceted human being. The school aspires to nurture its students on the values of democracy, solidarity and tolerance,[…] to cultivate graduates who are educated, free and independent, who contribute to society as citizens of the state of Israel and of the modern world.” It also states: “The school aspires to cultivate graduates who are committed to bettering society and improving themselves as individuals. The great challenge is to create an educational journey, at the end of which students will have acquired a political and social worldview that is guided by values of mutual respect, personal responsibility, fraternity and justice.” The school achieves a smooth integration of formal and informal education. The students too recognize that the social component is a characteristic of the school’s uniqueness and excellence. The school emphasizes education for values, as demonstrated in the variety of seminars in which the students participate, whether guided by the teachers or by outside experts.In the middle school, students consistently run their own committees, guided by adults. The rationale behind the committees’ work is to foster leadership, team work, mutual responsibility and, above all, a culture of contribution and giving. The process includes a training module titled “What, why and how we work.” Twice a year, special certificates are awarded recognizing the students who partake in the various committees and in the social activities of the middle school.Every year, the school holds six parties. Each grade level (9th-12th) prepares an annual party. All parties and ceremonies at the school are based on the students’ work: they write and edit scripts, decide on staging, build the set and execute the production. Occasionally these activities interfere with regular class attendance, but the staff and the boarding school counselors assist and accompany the preparations. By the time the performance or production is ready, nearly all of the students of the grade level are involved in one aspect or another of the event, and they consider it an experience that establishes their social identity as a grade level in the school.The school’s student council is very active, and school management is receptive to its initiatives, as long as these are accompanied and supervised by the social coordinator. The student council is responsible for arranging active recesses and producing special events. In addition, the student council manages a publication called "School A-LIVE," which reviews students’ creative and artistic endeavors. This is accompanied by an evening performance featuring the artists, which is also produced by the student council. Mid-year and end-of-the-year report cards mention the student’s involvement in social and community activities.Each year there are two student delegations that travel abroad: one is part of an exchange program between Israeli and German youth, and the second is a delegation to Poland that tours concentration camps and other sites related to the Holocaust.

3.1.4. CommunityExcellence —The School’s Relationship with the Parents

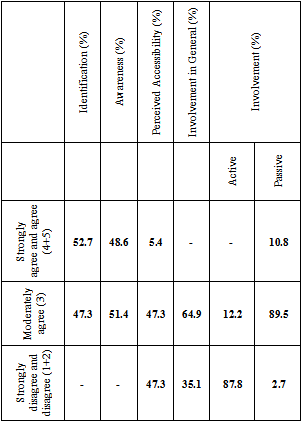

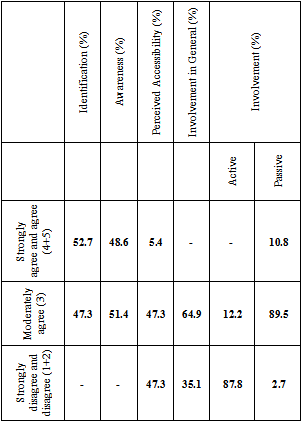

Recent years have seen an increase in parental involvement in the school. The school also makes a point of connecting with parents directly, by means of a weekly online newsletter that informs them of previous and upcoming events, and provides general information about school affairs. Nowadays many homeroom teachers communicate with parents via email, sending updates on the child’s performance at school and about school activities. In addition, parent-teacher meetings are held at least three times a year.At the opening of a new school year, the principal meets the parents and delivers a presentation about the school’s policies and the goals for the year. The Determined Involvement approach has created a new alliance-based language between the parents and the school; both the staff and the principal are confident about the strength of this alliance.Since 1998, when a parents’ council was established at the school, and until this study was conducted, the school’s management had reached several agreements with the parents’ council. The parents operate on the understanding that their ongoing involvement in the school’s activities is extremely significant and important; consequently, they decided to initiate approximately four or five one-day cultural events per year.In this study, parents’ participation was assessed using the Parents and School: Attitudes and Parental Involvement Questionnaire (see section 2.2). Only a small portion of the school’s parents responded to the questionnaire (12%, N=74); therefore, while the results do not represent the entire parent body, they do convey a general sense of the parents’ attitudes. Table 4. Results from the questionnaire "Parents andschool: attitudes and involvement" – School A

|

| |

|

Table 4 presents the relevant results. In general, most of the parents (65%) were involved in some way in their children’s classes or in their school life, although it is worth noting that none of the parents indicated a high degree of involvement, despite the existence of an active parent council. Most parents identified with the school’s mission and vision (53% indicated a high or very high degree of affiliation). None of the parents indicated that they do not identify with the school’s mission. About half of the parents (49%) reported that they were very aware of what goes on at school and none of the parents indicated complete lack of such awareness. Regarding the degree to which the parents believe that the school trusts them and their children, approximately half of the parents(47.3%) did not feel that the school respected either them or their children.

3.2. Success Story of School B - The Religious Girls’ Seminary

In religious schools in the public school sector in Israel, boys and girls study in separate schools during their high school years: girls in a seminary and boys in a yeshiva. School B seminary emphasizes intensive Torah studies, as well as social activities. The school day is divided between religious and secular studies, and students aim to obtain a matriculation certificate, as well as an acknowledgement of their individual religious achievements, which encompass spiritual development and personal attributes, as well as nd one’s devotion to the Torah, the Jewish people and the Jewish land. There are 425 girls attending School B seminary, studying in 16 classes of 25 students each. They come from an average socio-economic background, and most of the parents have a college education, which is typical of the population of the city where the school is located.

3.2.1. Organizational Excellence

The first characteristic of organizational excellence was the principal's leadership. The seminary was founded in 1999, as an expanding school, which began with grades 7-9. Its founder and principal until today immigrated as a child to Israel from Malaga, Spain. He knew he had to address two seemingly conflicting needs: the first was to show measurable proof of excellence, specifically, to help students graduate with a matriculation certificate and high grades; the second was to create a pleasant atmosphere so that the students would want to come to school, or as he put it: “so that the parents would be glad to send their daughters off to school.”Three years after its founding, the seminary had proven its ability to respond to the first need: 93% of the students passed the matriculation exams with a high average score. The second need had also been addressed: despite the heavy academic load, students arrived to school with a smile. A great sense of satisfaction was experienced by all.The main characteristic feature of the principal's leadership has been to enable the school staff to work with a great deal of freedom. Thus, staff members use their own discretion in making independent, professional decisions;the principal only asks to receive regular updates. When the staff or students show initiative, their efforts are welcomed by the principal, who not only, enables such initiatives to emerge and provides the final stamp of approval, butalso initiates his own spontaneous actions from time to time. The principal's leadership comes into play also as he trains the teaching staff and as a teacher at the school. He also manages an online forum, where students are able to receive an immediate answer to any question they pose. His approach combines humility and a focused determination (characteristic of Collins’ Level 5 leadership; Collins, 2001).The second characteristic of organizational excellence was the organizational structure and annual pedagogical plan. The school management level includes six members: the principal, the vice principal, the middle school and high school counselors, the social coordinator, and the administrative manager. Management meets every Sunday1 from 8-10 am to review the previous week and discuss and plan the present week. Throughout the calendar month, homeroom teachers attend three meetings: the homeroom teachers’ forum, middle- or high school level meeting for homeroom teachers, and one monthly meeting that features a guest lecturer. The meetings are run by the level coordinators, who are authorized by the Principal to manage the meetings independently.The annual work plan includes a pedagogical and a social plan. The principal does not interfere in the pedagogical planning and lets the relevant team members carry out their tasks; needless to say, he does review the outcome. Although the school has no organizational strategy, each member of the teaching staff is responsible for designing a module or a sub-unit in the seminary’s annual pedagogical plan. Staff members submit their sub-units to the subject coordinator, who then designs a plan for each grade level. The school’s general curriculum, which is managed by the grade level coordinators, consists of monthly plans, combined with special requests submitted by the students.In contrast to the staff’s autonomy in devising a pedagogical plan, the principal is very much involved in the design of the social program, which consists of two annual themes.The educational staff at the seminary values the students’ opinions; therefore, at the end of every school year, students are asked to provide feedback via an anonymously filled questionnaire, which aims to gather information regarding the social and academic atmosphere and the teacher-student relationships at the school.Fiscally, the school manages its own budget, which is derived from the following resources: the Ministry of Education (which funds secular studies and activities which last until 1:30 pm), the municipality, and the parents. The parents’ contribution is $1,200 annual tuition (which was the lowest tuition among the seminaries). School hours extend until 4 pm, and the parents’ contribution covers the later portion of the day, which is considered a secondary course of studies. There is a committee that reviews the cases of families that are unable to cover the costs.The third characteristic of organizational excellence was thestaff’s sense of functioning capacity. The results obtained from the Staff Mapping Questionnaire (section 2.2) indicate that the staff feels that it is functional at a very high level (90%). Table 5 presents a summary of these results. Interestingly, a of the staff members indicated a low level of functioning on any of the items.As regards the school’s goals, 94% of the pedagogical staff is very familiar with these, although the wording of these was not uniform. Most teachers mentioned academic achievements as one of the school’s major goals, as indeed it is mentioned in the mission statement. Despite the fact that all of the teachers are expected to relate to the function of religion in the school, not all did so.Similar questions to those on the questionnaire were posed to the pedagogical staff through personal, open-ended interviews. Findings from the interviews corresponded with findings obtained via the Staff Mapping Questionnaire. The staff members of the school were willing to discuss their feelings openly, and they expressed their affinity with the school, its values and its leader both in written and oral form. Notably, almost all of the teachers reported that they considered the principal to be a pedagogical authority.| Table 5. The pedagogical staff members' feelings about the functioning of the staff of school B girls religious high school (N=33) |

| | | Percentage of teachers who feel that the staff functions at a very high level | Percentage of teachers who feel that the staff functions at a very low level | | General Function | 90% | - | | Targets | 94.4% | - | | Delegation of authority | 91% | - | | Flexible roles | 83% | - | | Relationship and communication within the staff | 83% | - | | Productivity (operational productivity | 83% | - | | Recognition and appreciation | 76% | 2% |

|

|

3.2.2. Pedagogical Excellence

The first characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the high level of student retention. This seminary does not select from a pool of candidates, but rather is committed to accept all religious girls from the municipality and from nearby towns. It does not expel students, and although there is a very low dropout rate, the reasons for this are varied, such as a family move or the need for a boarding school setting.School B is the only religious high school (including seminaries and yeshivas) in Israel that does not rely on selective admittance; nonetheless, the students’ academic achievements are not significantly different from those of students in the selective religious schools. Students in most of the religious seminaries necessarily come from a high socio-economic background; in contrast, School B accepts anyone who wishes to attend, including girls from a secular background who wishes to receive a religious education. The second characteristic of pedagogical excellence was academic achievements. The academic achievements of the young women are above the national average. Furthermore, there is a high degree of correlation between students’ yearly grade point averages and their matriculation averages. The school aims to enable students to obtain a matriculation certificate that is competitive in terms of both grades and credits earned; consequently, extra lessons are offered in class, group and individual settings.A review of the pertinent data indicates that the rate of students who graduated and successfully completed the matriculation requirements in the school’s first 4 years increased from year to year, as is shown in Table 6. | Table 6. Rates of students attending and succeeding in the Matriculation exams (first 4 years of school) – school B |

| | 2006 Fourth year of school | 2005 Third year of school | 2004 Second year of school | 2003 First year of school | | | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Attending matriculations (%) | | 97% | 95.5% | 96% | 92% | Eligible for matriculation certificate (%) | | | 5 | 3 | 2 | Outstanding CEO |

|

|

The students take their studies extremely seriously. The staff has been successful in getting the students to internalize the notion that homework assignments are intended to help them learn. Indeed according to teachers’ reports, the students are well aware of the significance of their academic achievements.Thus, although the school-day often ends as late as 5:30 pm, students nevertheless apply themselves to their assignments, and while these may not be collected by the teacher, thestudents understand perfectly well that if they do not complete the assignment, they will not be able to follow or participate in class the next day.The school attributes part of its success to the fact that it is an all-girls school.In general, the academic achievements of students attending separate sex religious high schools are significantly higher than the achievements of their counterparts in the secular public school.The school has a tradition of notifying a student’s parents when the child has obtained a score of 100% on a test. It is important to note that the principal, attributes great importance to students’ academic achievements, and he personally signs each report card and writes an individual comment for each student.The third characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the curriculum. The curriculum comprises secular and religious studies. It is based on a notion of “the ideal graduate,” and includes an ethics as well as an academic component. The former is conveyed through homeroom class discussions, personal conferences with the students, students’ the assignment of a social responsibility to each individual student, preparations for national service,2 special classes on sex education pertinent to the religious way of life, and workshops on non-violent spousal relationships. The component of academic education includes preparation for a matriculation certificate of 27-30 credits, supplemental tutoring in group or individual settings, learning strategies, and workshops on coping with test anxiety. In the 10th grade, students begin a curriculum that consists mainly of major study areas in a few select subjects, which the students hadselected earlier, through a preliminary, guided process. There are four fields of concentrated studies offered: social studies (two credits in psychology, two in sociology and a one-credit final research paper); communications (nine credits); biology (five credits) and physics (five credits).Teaching methods are varied and numerous and include, for example, computer assisted learning in several subjects, using drama in middle school Bible classes, as well as arts, movies, educational excursions, guest lecturers, options to research a topic of choice and interdisciplinary studies. The staff emphasizes the use of Gardener’s eight types of intelligence.Corresponding to the school’s emphasis on combining religious and secular studies, a great deal of attention is focused on a curriculum of school trips and geography of Israel. The school trips program encompasses all six years at school and aims to let the students acquire a profound knowledge of Israel’s six major regions.The fourth characteristic of pedagogical excellence wasmanaging diversity. To assess students’ initial level, the school administers an entrance exam. A student who does not pass is obligated to either attend the school’s preparatory course or close gaps using parent funded private tutoring before the school year commences. If she is unable to catch up to the class level, individual tutoring at school is arranged at the start of 7th grade.The staff leads the students’ to academic excellence first and foremost by instilling in them the confidence that if they truly want to, they can succeed. There are several projects that work to apply this philosophy. In addition, once a week the principal meets with a group of weaker students who stand to benefit from his encouraging and convincing words. Online classes are available in grammar and math. As part of the attempt to boost students’ self-confidence, there are courses also on self-awareness and test anxiety.Starting in 7th grade, classes in English and math are divided into levels, due to the variance in students’ levels as they enter the school. In the middle school, the extra tutoring classes are taught by teachers who are not on the school’s staff, but who coordinate with the staff members regarding the lessons and materials reviewed. High school students also receive extra class hours to assist them prior to matriculation exams. These are funded by the Ministry of Education and are particularly helpful for the weaker students. Three times a year, pedagogical staff meetings dedicated to reviewing each class. During such meetings, decisions are reached and plans are set in motion to assist and address the current academic difficulties. These meetings are immediately followed by more intimate ones between the homeroom teacher, the school counselor, and the pedagogical coordinator, to determine how best to implement the decisions made during the general staff meetings. Throughout the academic year, staff meetings are held also per subject, to consider how to professionally address the diverse levels among students: the weaker students, the higher achievers and those in the mid-range of the normal curve. In 10th grade, as students begin to face the heavy burden of matriculation exams, several hours are devoted to teaching life skills, which focus mainly on time management.To enable each student to work at the highest level of her individual potential, the school offers guidance in schedule planning, as well as personal guidance throughout the school years. An individual contract is drawn up with each and every student, in which she states her commitment to pursue specific goals. The school is committed to provide, as necessary, extra assistance in the form of concentrated study days, extra tutoring classes, multi-level classes in particular subjects and summer courses. In addition, personal follow up meetings are held with individual students to gauge and assist in their progress, and parents receive constant updates. The school also ensures that matriculation exams are spread out over time, so that students do not face multiple exams in rapid succession. All of this requires qualified teachers, curriculum planning, training and guidance for teachers, subject based workshops, and coping with obstacles and distractions.The fifth characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the quality of life at school. There is a clear behavior code at school, which includes following the Jewish commands according to the Torah, as well as the religious tenets regarding respectful and modest behaviors. The code was written by the school’s management, and parents and students receive copies before the start of the school year. Both the students and the teachers note that there is neither violence nor drug use at the school. When asked about violence, the young women draw a distinction between “causing disturbances during class time” and “violence.” They also mention that the teachers’ approach in responding to such disturbances is supportive rather than angry. When someone is disruptive, the teacher asks her to “remove herself and return when she feels ready.”The mutual affection between the students and the staff is part of the general atmosphere at the school. According to the school’s approach, there is no need for penalizing, since any problems that emerge cannot be resolved through punishment. Problems fade because they are not fueled; the school responds only to the positive, or in the words of the principal: “You can’t cast away the darkness by using sticks, but create even the smallest light, and the darkness recedes.” The principal wrote the school’s anthem and he can be heard reciting it on the school’s Website. Once a week, the entire school gathers to receive the Sabbath according to the Jewish tradition. On this occasion, each homeroom teacher selects one of her students to come up and receive honorable mention and a book with the dedication “to the excellent student of the week.” In a period of 30 weeks, there is ample opportunity for each student at the school to receive this honor at least once over the course of the school year. Clearly, the meaning of “excellent” in this context does not refer solely to academic achievement. The teacher may choose to honor a student who made a special effort to overcome difficulties, or a student who demonstrated remarkable dedication to a social activity.The sixth characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the school’s pedagogical staff. There are 33 teachers at the school, and as we were repeatedly told, they all have a sense of mission. We were surprised to find that more than one third (12) hold less than a 50% position at the school, which suggests that the staff’s commitment to the school is not necessarily related to amount of hours spent at the school, as findings from the School A school suggested. Approximately half of the staff (49%) holds an undergraduate degree (close to the national average rate of 48.4%), and nearly half (49%) holds a Master’s degree (the national average rate is 32.5%). Only one of the teachers holds a senior position (2%), whereas the national average rate is 9%). The ratio of male to female teachers in the girls seminary differs from the national pattern: there are 29 female teachers (88%, compared to the national rate of 70.8%) and only 4 male teachers. Most of the staff members have been teaching in the system for over 15 years, two of them for over 35 years. This was particularly useful for the purposes of this study, since these veteran teachers could attest to the changes the school had undergone.The staff’s sense of mission is complemented by the feeling that the school feels like a second home, a combination that undoubtedly contributes to the school’s excellence. Every single teacher volunteers to teach supplementary classes during vacations and on Fridays after school, a demonstration of good will that cannot be found at every school. When asked to describe the teachers, the students immediately responded: “they understand and know each one of us, recognize each student’s particular inclinations and tendencies, and they connect to that.” The students are aware of the teachers’ sense of mission, and they feel they can consult with them on any topic, from academic to personal. Given that the majority of female teachers are themselves graduates of an all-girls seminary, the students often seek consultation on extracurricular activities, for example, when in need of ideas and recommendations for their youth group activities.All of the staff members teach in both the middle school and the high school. The entire staff is selected by the principal. When the school was first established, there were ten candidates contending for each position. In the selection of teachers, the principal is guided by three criteria. The first is professional: the teacher must be an expert in the field that he or she teaches; at the school, all staff members teach only the subject in which they majored. The second criterion is value-based: the candidate’s educational background is important, since the teachers necessarily serve as a model for the young women. The third criterion is the candidate’s interpersonal skills, which are assessed through a personal interview and by checking the candidate’s references. Should a newly hired teacher be found unsuitable, the mistake is addressed in the course of the school year, whereby a senior teacher attempts to help and guide the new recruit; if this does not result in sufficient change, the teacher is transferred to another school.The seventh characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the professional development of the staff. All staff members are required to participate in professional development workshops, or pursue a higher academic degree. According to the principal, “there is no teaching without learning.” Every three weeks the school offers a workshop related to an annual theme.All of the staff members teach in both the middle school and the high school. The entire staff is selected by the principal. When the school was first established, there were ten candidates contending for each position. In the selection of teachers, the principal is guided by three criteria. The first criterion is professional: the teacher must be an expert in the field that he or she teaches; at the school, all staff members teach only the subject in which they majored. The second criterion is value-based: the candidate’s educational background is important, since the teachers necessarily serve as a model for the young women. The third criterion is the candidate’s interpersonal skills, which are assessed through a personal interview and by checking the external references that the candidate provided. Should a new teacher be found unsuitable, the mistake is addressed in the course of the school year, whereby a senior teacher attempts to help and guide the new recruit; if this does not result in sufficient change, the teacher is transferred to another school.The seventhcharacteristic of pedagogical excellence was the professionaldevelopment of the staff. All staff members are required to participate in professional development workshops, or pursue a higher degree. According to the principal, “there is no teaching without learning.”Every three weeks the school offers a workshop related to an annual theme. The eighth characteristic of pedagogical excellence was the teaching staff’s definition of excellence. The majority of teachers at the seminary emphasized the development of excellence as a clearly defined goal, and they explained this goal: “to foster excellence as a way of life, in every realm and for every individual,” “the school believes in the abilities of each and every student.” Clearly, they distinguish between excellent achievements and excellence in everyday performance, as they referred to the goal of “enabling students to progress, each according to his or her individual abilities,” and the need to “address the variance among the students.”

3.2.3. Social Excellence

Social activities are emphasized at School B. The seminary’s goal is to see its graduates become well-educated Jewish women who abide by Jewish commandments and contribute to the Jewish nation. Thus, social activities include seminars, communal Sabbaths, excursions to observe a Jewish tradition, lectures, projects on varying themes, workshops, whole day seminars, volunteer work, games for group dynamics and sing-alongs. Much attention is devoted to the subject of peaceful coexistence between the religious orthodox Jews and the secular Jewish population. The student council plays a central role at the seminary, and representatives of the seminary’s student body also attend the municipal student council. The students on the council show initiative and unrelenting effort in their attempts to provide activities on a wide variety of topics.Due to the significance that the school attributes to moral values, the students partake in several programs that educate and promote certain values. Among these is the national Social Responsibility Assignment, in which students volunteer in various capacities. As part of this program, the students at the seminary dedicate 60 hours a year to volunteer at various organizations. At times the students themselves organize related activities, which are well received by the school management. The fact that the students participate in part of the decision making processes on social issues contributes greatly to their high degree of affinity with the school. Furthermore, the general sense of support they enjoy makes school feel like a “second home.” School is tolerant when it comes to activities that take place beyond the confines of the school, and demonstrates a great deal of flexibility by rescheduling the school’s plans whenever possible if they clash with social activities. Responses of this kind make the students feel that they are respected by the school.The seminary’s official policy opposes having girls fulfill the mandatory military duty, although for boys military service is considered a Mitzvah (a religious good deed). Replacing military service with national service, however, is very much encouraged. Graduates stay in touch with the school, as demonstrated by wedding photos of graduates’ displayed in the principal’s office. This is part of the agreement between the principal and the students, whereby they send him a photo of themselves once they are married. The principal and staff are invited to students’ personal events, and occasionally he, being a Rabbi, officiates at their wedding ceremonies

3.2.4. CommunityExcellence - The School’s Relationship with the Parents

Currently the parents are pleased with the educational direction of the seminary. Early on, there was much turmoil surrounding this issue, since the community is not homogeneous ideologically, and parents wanted to lead with an approach that corresponded to their preference. Over the years an acceptable ideological direction was formulated. The first year, however, gave rise to a major crisis, during which a tender was issued seeking a new principal for the seminary. The crisis was resolved when the principal managed to regain the parents’ trust, and they finally supported his solution. Parental involvement is not particularly encouraged at the seminary. There are two reasons for this: first, the students themselves, as typical teenagers, prefer to lessen parents’ influence; and second, the families belong to many varied streams within Orthodox Jewry. However, the school makes sure to keep parents informed about all of the developments and activities at the school via newsletters and evening gatherings held to introduce a particular theme. In addition to the seminary’s Internet site, a school paper is published twice a year, which presents the main events of the school year, and a monthly newsletter is sent to the families directly.The parents’ council meets every six weeks to receive an updated report prepared by a council representative, and members of the council raise issues for discussion. Parents also assist the Principal by rallying to pressure local authorities when required.We were unable to ascertain the parents’ degree of affinity with the school or obtain parents’ comments, since for some reason, which remains unclear, the parents did not fill out questionnaires. Two attempts were made to deliver the questionnaires to the parents, both of which failed. However, based on discussions with parents and residents, it seems that the parents feel a very high degree of affinity with the school.

4. Conclusions

As emphasized in the discussion, while the outcome of analysis of the success stories did not render a new theoretical model, it did nevertheless identify seven major factors that that led these schools to become excellent schools.1. The principal’s leadership: The characteristics of both of the principals correspond to those of a level 5 leadership (Collins, 2001). Both principals have clear priorities, yet they attribute the organization’s success to the pedagogical staff (along with the service and maintenance staff). They consider the staff’s work to be significant and of high quality, while they see themselves as participants in and supervisors of this important endeavor. They do not cast themselves in a leading role, or consider themselves at the forefront of this mission. Both principals cope with dilemmas and difficulties that arise, while maintaining an appreciative attitude towards the teachers, parents and students in situations of turmoil.2. Organizational structure and annual pedagogical plan: The two schools described in this study demonstrated excellent organization and planning, although they differed in their organizational structure. Both schools described a period in the organization’s’ history when they had to work to overcome obstacles that impeded the schools’ progress towards excellence. In both cases, having not only a well-defined mission which is known and understood by all, but also clearly outlined goals and objectives helped put in motion a detailed work plan that eventually led to excellence.3. Academic achievements: Both of the schools described herein strongly emphasize academic excellence and achieving high grades. Both schools have a dual emphasis in this regard: they aim not only to increase the percentage of students eligible for a matriculation certificate, but also to guide graduates to obtain a matriculation certificate with a strong credit basis. Both schools also showed a very high level of student retention.4. The school’s pedagogical staff: A high degree of affinity was noted between the teachers and the school’s goals in both schools. In each school, the staff is proud of the school and its achievements. In part, this affinity was forged by giving the staff positions of authority within the organization, which creates motivational incentives and a strong allegiance to the organization. Notwithstanding, it was found that the majority of the teachers at School B held only part time positions yet felt a great affinity with the school. At both schools, professional development was an integral part of the organizational culture of “a constantly evolving organization.” On an individual level, professional development took place outside the schools, while internal professional workshops served to support the advancement of predetermined topics promoted by the school. Thus, internal workshops were part of the annual work plan.5. Student's diversity:The schools devote particular attention to addressing the needs of the strongest and the weakest students without compromising the needs of those in the range between the two groups. In addition, students with difficulties or learning disabilities are identified and the staff –with additional tutors– gathers to formulate a work plan. The schools reviewed exhibited a great deal of empathy and understanding towards these students, and often the principals managed to fund extra tutorial classes. However, not only the weak students draw attention at these schools; the educational staff works diligently to present all of the students with challenging tasks and projects, as a means of inspiring excellence.6. Quality of life at school: In this research, the quality of life at schools was demonstrated by lack of reported violence and by social and youth leadership activities. The absence of violence in both schools was probably due to the clearly-defined conduct rules, relayed through a school regulation handbook, which were carefully and constantly enforced. At School A, discipline is addressed through an educational process, rather than through punishment. The entire school participates in the Determined Involvement program, fostering the development of a common language of normative behavior. In School B, the absence of violence may be explained by its being an all-girls school. Both schools encourage students to take on leadership roles, both in school and beyond.7. The school's relations with the parents:The school's relations with the parents. As parental involvement has been shown to contribute significantly to school success and excellence, the study evaluated the parents’ opinion of the school, using two parameters: the parents’ degree of affiliation with the school’s mission and vision, and their awareness of what transpires at the school. The association between parental involvement and excellence was confirmed only at School A, due to lack of data from the parents of School B. At School A, parental affiliation with the school’s mission and vision was indeed very high. In both schools, the parent councils offer an appropriate framework for parental leadership. The communication between the parents and the school is excellent, and it appears that parents are welcome, and their concerns are heeded and addressed.The main goal of this study was to analyze a school of excellence. The approach was to review success cases, so as to observe and learn from them about the qualities that enable the creation of an organizational culture in which excellence is a process that leads to success.The combination of research methodologies (observations, interviews, focus groups, questionnaires and textual analyses) made it possible to consider the issue from multiple perspectives and to analyze the parameters of organizational culture as well as the methods of organizational development. It also enabled us to observe the attitudes that the various populations at schools, i.e., students, teachers and parents, exhibit towards the organization and its components, and the ways in which they conceptualize their roles.

Notes

1. Israel functions on a 6 day work week; public schools run Sunday through Friday.2. Typically religious girls do not compete mandatory military service, instead they volunteer for national service.

References

| [1] | Lipsitz, J and West, T (2006). What Makes a Good School? Identifying Excellent Middle Schools.Phi Delta Kappan, 88, 57-66 |

| [2] | Hoy, K.W. &Sweetland, R.S. (2001).Designing Better Schools: The Meaning and Measure of Enabling School Structures Educational Administration Quarterly, 37(3) 296-321. |

| [3] | Wallace Foundation (2007). Annual report. New York: The Wallace Foundation. |

| [4] | Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A & Hopkins, D. (2007). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. Birmingham: NCSL |

| [5] | Walker, J. (2009). Reorganizing Leaders’ Time: Does It Create Better Schools for Students? NASSP Bulletin, 93 (4) 213-226. |

| [6] | Cotton, K. (2003). Principals and student achievement: What the research says. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. |

| [7] | Nettles, S. M., & Herrington, C. (2007). Revisiting the importance of the direct effects of school leadership on student achievement: The implications for school improvement policy. PeabodyJournal of Education, 82(4), 724-736. |

| [8] | Collins, J. (2001). Good to great.London: Random House Business Books. |

| [9] | Fisher (2008). The road to excellence: Success stories of schools. Jerusalem:Henrietta Szold Institute (Hebrew). |

| [10] | Rosenfeld, J., Sykes, Y., Dolev, T. & Weiss, Z. (2002). How to turn "Learning from Success" to a lever for development of school learning. A national experimental program of the Department for high schools schools and JDC - Brookdale Institute. Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute Publications (Hebrew). |

| [11] | Carla, W. & Wendy, S. (2008). Grounded Theory. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. London: SAGE Publications Ltd |

| [12] | Blanchard, K., Randolph, A. &Grazier, P. (2005) Go Team! Take Your Team to the Next Level. Berrett-Kohler Publishers, Inc. |

| [13] | Holliday, M. (2001). Coaching, mentoring & managing. NJ, FranklinLakes: Career Press. |

| [14] | Maxwell, J. C. (2001). The 17 indisputable laws of team work. Nashville, Tennessee: Nelson Business. |

| [15] | Friedman, A.I & Fisher, Y. (2003). Parents and school: attitudes and level of involvement. Jerusalem:Henrietta Szold Institute(Hebrew). |

| [16] | Omer, H. (2000). Restoration of parental authority. Tel-Aviv: Modan.(Hebrew) |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML