-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2012; 2(5): 136-142

doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20120205.05

There’s an App for That: How Two Elementary Classrooms Used iPads to Enhance Student Learning and Achievement

Corey McKenna

School of Education, Whitworth University, Spokane, WA, USA

Correspondence to: Corey McKenna , School of Education, Whitworth University, Spokane, WA, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purpose of this study was to research how two elementary school classrooms used iPads to enhance student learning and achievement. Participants were two first-year teachers’ classrooms in a small one-school school district in Central California that was comprised of 38 students. Each classroom contained a classroom set of iPads used during English Language Arts and Mathematics lessons. The experimental research design study was conducted over a 3-month period beginning in January 2011. Two sets of groups—a control group and an experimental group—were given both iPad and non-iPad lessons. Data was collected for both groups and analysed. Findings included small increases in both classrooms in reading and math when iPads lessons were compared with lessons that were conducted in a traditional non-iPad method. It was concluded that the use of iPads enhanced student learning and achievement and served as another learning modality for elementary school students.

Keywords: Technology, Elementary Education, Ipad, Student Learning, Achievement, California

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In some elementary schools, a paper and pencil is no longer needed to teach a math lesson. Now thanks to Apple’s new iPad, there’s an app for that. Introduced in 2010, the Apple iPad heralded a new age of technological convergence and promised to bring mobile technologies into every home and classroom[11]. Students can be more engaged than ever before and create their own math equations using the Alien Equation app on the iPad (“Apple”). The same holds true for learning grammar as well. Sentence structure diagrams on a chalkboard are a thing of the past now that grammar apps can be downloaded for the iPad through “Tap To Learn” software. In many ways, these new forms of communications technologies have drastically changed the environment in classrooms and the overall student attitude towards learning (“Technology and Education Reform”). With technology available at a child’s fingertips, they become the ones to manipulate the activity and can actively make decisions regarding the lesson.The iPad is just one example of the many recent improvements in technology that have contributed to advancements in elementary education over the past decade. With a global boom in terms of communications technology, educational achievements have been fostered, and these improvements have made it possible to expand and expedite learning for children in the classroom. While there are numerous technologies available to teachers, one of the biggest technologies in terms of communication has been the increased use of the Internet for academic purposes. According to a 2002 Pew Research Study on student use of the Internet for school, with the exception of very low-income school districts, “it is now the case that the Internet is as common a school fixture as lockers and library books” (“Digital Disconnect”). Furthermore, this study also concluded that “One of the most common activities that youth perform online is schoolwork” (“Digital Disconnect”). Although this study and many others like it are helpful for understanding the many academic uses of technology, the current research fails to address very specific regional areas.One of the primary motivators for a school to use iPads was to transition to digital textbooks. Schools believed digital textbooks are easier to use, lighter to carry, and cheaper for families. The other interest in getting digital text books that they were more interactive and could be updated to contain more current information. Schools believed digital textbooks are more engaging than paper. However, many school districts would continue to play the conservative wait and see card. But some say they were committed to moving ahead with the iPad and getting students using them as soon as possible.With the advancement of mobile technology, educators have become more interested in using mobile devices in support of learning activities, and many studies have been conducted to evaluate the impact of an interactive mobile learning environment on students learning[4,15]. However, little research has been carried out to examine the educational application of the iPad, one of the touchable forms of mobile devices, in the elementary science classroom. Reference[14] was the first to examine iPad as an educational tool in comparison with netbooks and laptops that are commonly used in school settings. Reference[1] discussed features and applications available on another mobile device, iPod Touch that might impact student learning across the curricula.This study will fill the gap in the existing research by focusing on communications technology in elementary school classrooms in the rural area of central North Carolina. It will serve to define exactly which types of technologies are being implemented in elementary school classrooms and identify what the possible disadvantages are as well. In addition, this study will highlight the newest technologies for communication and seek to predict the future of technology in the classroom. While technology has become critical in education, the use is different across states and this research focuses on a specific state in a specific location by talking to teachers who use technology in the classroom every day. The research questions that guided this study was as follows:• How does the use of an iPad enhance student learning in two elementary classrooms?• How does student achievement increase through the use of an iPad in two elementary school classrooms? Therefore, the purpose of this study was to research how two elementary school classrooms used iPads to enhance student learning and achievement.

2. Literature Review

- The state of education remains one of the most highly debated topics in the country, yet there was surprisingly little research on the current relationship that exists between mobile technology, such as the iPad and iPod Touch, and education. Gradually, over the past few decades, various forms of communications technologies have been integrated into classrooms. This approach has been taken as a means of improving education and catering to different learning styles as well. The following review of the existing scholarship covers a key learning theory as well as the research to date on communications within the realm of education.The existing research shows that when technology was first introduced into classrooms, teachers were uncertain about how it should be incorporated. One study specifically looked at the factors affecting early technology use and determined that “there are conflicting ideas about the value of technology and hence conflicting advice to teachers about how technology should be used in schools”[16]. Some of the contributing factors to this cause include the constant changing nature of technology as well as the unreliability and lack of reliable support. In related research, it was also determined that while technology is a valuable resource, it should not be used to teach everything. For some lessons, technology isn’t necessarily the best means of teaching, and more importantly, as just “one tool among many, technology cannot be expected to change bad teaching into good”[10]. As a whole, it is most appropriate to use technology in the classroom for concept development and critical thinking activities. In recent years, the use of iPads (and other electronic devices, such as the Amazon Kindle) has impacted reading in the classroom. Reading electronically impacted on the way an individual comprehends what is read. “Web text reading was different from print text reading because web text has additional features”[12]. It has also been noted that reading web text for inquiry leads to less thought and evaluation[2]. While this study was not using web text, teachers had chosen to use the eBook format. This format provided us with more than print text, as, for example, each word is hyperlinked to an inbuilt dictionary. Reference[9] stated, “electronic texts that incorporates hyperlinks… introduce some complications in defining comprehension because they require skills and abilities beyond those require skills and abilities beyond those required for comprehension of conventional, linear print.”In one of the more recent articles relating to this subject, it describes how “virtual education,” or teacher and student interactions that are computer-mediated, have grown from being a novelty to commonplace in the classroom. It is no longer surprising that an educational institution would offer some form of online class, and the existing statistical data clearly support this notion. “In a non-random 2007 survey of school districts, as many as three out of every four public K-12 school districts responding reported offering full or partial online courses”[5]. This is one of the more complex and challenging areas of communications technologies in education because the rapid growth of this phenomenon prompts policy changes, questions of cost, and funding from officials and school boards. In addition to these numerous challenges, there is also the issue of the Internet as a distraction to students. While some websites can be filtered due to age inappropriate content, there is concern from teachers about “competition from Web sites put up by ESPN, CNN, and CBS sports, as well as myriad other pop culture sites that are not on the filter list but distract attention in the classroom”[8]. Although the Internet can be a great classroom resource, teachers need to constantly play the role of a monitor for online distractions. Many researchers[3,7] have asserted that the millennial learners need to be taught using the technology they are accustomed to. They argue that this is not currently happening with many types of technology. If this is indeed the case, the development of pedagogies to improve the on-demand asynchronous, anywhere / anytime learning styles of the millennial learners would not have occurred yet either. The personal on-demand nature of the podcast / iPod relationship allows participants to focus on what they determine is the necessary material to be at any given time. Building the developing pedagogical understandings around this relationship is a necessary step in the evolution of the use of this technology in educational contexts within contemporary society. An appropriate pedagogical framework to assist educators in the incorporation of this technology within educational contexts does not yet exist in the literature.In another, not quite as recent resource, technology is seen as a benefit and described as helping to reinforce critical skills. On the topic of inquiry-based curriculums that deal with gathering, evaluating, analyzing and presenting skills, it has been argued “technological tools exist for each of these skills. Both students and teachers need to be aware of the choices they have so that they effectively use the right tool for the job at hand”[6]. Technology in this case also takes learning one step further because it can offer so many supplements to plain text. “Classroom research today takes the text-based references familiar to most adults and augments them with CD-ROMs containing music, speeches, diagrams, animations and film clips”[6]. This resource also explains how technologies in the classroom can prompt education reform as far as using it to include and plan goal-setting techniques.Public schools throughout the country have started to embrace the use of iPads in the classroom. More than 200 Chicago public schools applied for 23 district-financed iPad grants totaling $450,000; the winners each received 32 iPads, on average — for a total of 745 — as well as iTunes credit to purchase applications. The district is now applying for a $3 million state grant to provide iPads to low-performing schools next year. The Virginia Department of Education is overseeing a $150,000 iPad initiative that has replaced history and advanced-placement biology textbooks at 11 schools. In California, six middle schools in four cities (San Francisco, Long Beach, Fresno and Riverside) are teaching the first iPad-only algebra course developed by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Even kindergartners are getting their hands on iPads. Pinnacle Peak School in Scottsdale, Ariz., converted an empty classroom into a lab with 36 iPads — named the “iMaginarium” — that has become the centerpiece of the school because, as the principal put it, “of all the devices out there, the iPad has the most star power with kids”[14].In reviewing the existing literature on the subject of communications technologies in education, it can be seen that there was a gradual shift over time in how exactly technology has been implemented in the classroom. The earlier literature deals with the very basics of technology, defining it and even stating possible impacts or repercussions. In a review of a dated piece of literature, visual presentations are considered for learning. What is completely commonplace in classrooms and during presentations today, once started as a unique concept. Programs such as Microsoft PowerPoint can create “presentations suitable for the classroom by offering a multimedia environment for concepts and ideas important for student understanding”[13]. Furthermore, multimedia Clip Art, pictures, sounds and movies can be added in to enhance the final product. While communications technologies have certainly come a long way over time, little is currently known about what the most popular forms are today for elementary schools and how teachers implement them within their classrooms and individualized curriculums. This study will fill the gap and create a greater understanding of how education can benefit from improvements in communications technologies.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

- Students belonged to a one-school school district, located a small community in the Central Valley of California. It was a K-8 public school with close to 100 students. 56% of the students were on free and reduced lunch and 7% were English Learners. The school had a 620 API score in 2010-11, a 68-point growth from the previous year. The first and second/third grades were currently the only grades that had classroom sets of iPads.The two elementary school teachers who participated in this study were brand new, first-year teachers. Olivia, a 26-year-old female, taught first grade. It was her first year as a teacher. Her class contained 18 students, who ranged in age from five to six years old. There were 10 boys and eight girls. The ethnic background of her class consisted of the following make up: 82% European American, 17% Latino/a, and 1% other. Olivia’s class did not take the California Standards Test, since first grade classes were not required to take it.Katie, a 27-year-old female, taught a 2nd-3rd grade combination class. It was also her first year as a teacher. Her combination class contained 20 students. There were 11 boys and nine girls and ranged in age from six to eight years old. This class consisted of mostly second graders combined with lower level third graders. The ethnic background of her students were 80% European American, 18% Latino/a and 2%other. Katie’s class was the only one tested on the yearly California Standards Test (CST). For 2010-11, 20% were at or above proficient level in both mathematics and English Language Arts.

3.2. Data Collection

- An experimental research design was used during a 3-month period that began in January 2011 to assess the iPad’s potential to enhance student learning in these two classrooms. Both iPad and non-iPad lessons were observed. Throughout each month, this study compared iPad methods with traditional (non-iPad) methods and engagement for students in both grade levels during math and reading/language arts lessons. Controls groups were not used due to the age level of the students. Therefore, the entire class either used or did not use iPads for those observed lessons. Lessons were approximately 45 to 60 minutes in duration and comprised of instruction in reading or math and activities in the same subject areas. Each student was assigned a numbered iPad designated by the teacher (and required by the school). This allowed him or her to make their own annotations and save their work during each lesson and activity.Data was collected throughout each month with researcher and teacher observations, student interviews, and student work. The research also conducted interviews with both teachers in December 2010 in order to collect anecdotal information to qualify the quantitative results. This was to determine attitudes towards the use of iPads, especially since both teachers were first-year teachers. Olivia had used an iPad in an Apple Store; Katie owned a first-generation iPad. Both teachers were enthusiastic about being involved in the study and increasing student engagement and achievement with her respective students. Both teachers had the opportunity to take iPads home to prepare for lessons and activities. Both teachers were required to spend a minimum of two hours per day on developing reading and math skills in order to know how to properly and effectively incorporate the iPads with the classroom. This allowed for both teachers to have purposeful connections between technology, teaching and learning experiences in each classroom.

3.3. Analysis

- This study made use of qualitative data collection methods the included formal and informal interviews and surveys as well as observations. Data was coded in order to make conduct analyses of what exactly occurred as result of the iPad usage. Furthermore, quantitative methods were used for statistical analysis based on student work and any pre- and post-testing done to determine existing ability and comprehension and understanding of the reading and math concepts.

4. Results

- Today’s K-12 students are very different from even their recently graduated peers. These students are digital natives, a term attributed to futurist Prensky (2001) to distinguish those who have grown up with technology and those who have adapted to it. Students today live in a world where digital technology is part of the texture of their daily lives. They have never known a world without technology. It is their native language and they expect to use it in school. Even at a very early age, students are exposed to technology in the classroom. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to research how two elementary school classrooms used iPads to enhance student learning and increased student achievement.This is a challenging time to be a teacher where change occurs rapidly. New policies and changing demographics are making schools more diverse than ever. Attitudes towards the technological advances can vary greatly. In this study, both teachers had a positive attitude towards the use of iPads in the classroom and it carried over to the attitudes of students in both grades.

4.1. Student Engagement

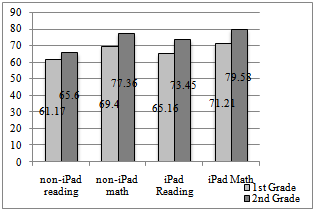

- Reference[8] discussed how traditional computer-supported learning has demonstrated an example of how to promote student engagement in the classroom. With new advances in technology, new opportunities arose for a wider range of student engagement. As technology became readily available, the primary focus of study by Price was to discover how different types of student engagement interactions engendered reflection in learners, and what kinds of patterns of communication might emerge in the process of the different interactions.In Olivia’s first grade classroom and Katie’s second grade classroom, both teachers noticed through her observation log that students were engaged more often during the use of iPad lessons than when they were not being used. In fact, based on both observation logs along with the researcher’s observation logs, it was determined that both grades were engaged more often in iPad lessons than in non-iPad lessons (see Figure 1). The average number of minutes of engagement during reading and mathematics increased when students used the iPads compared when they were not using iPads.

| Figure 1. Student engagement (in minutes) |

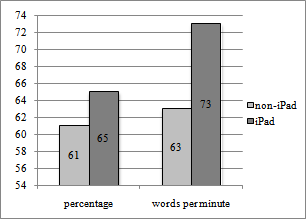

| Figure 2. 1st grade Reading Fluency |

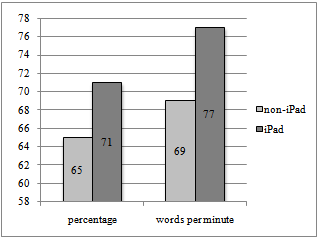

4.2. Reading & Language Arts

- In first grade, during the 3-month study, the average reading fluency increased significantly at a rate considered normal for that same period of time. Reading fluency has two components: accuracy and speed. It was also divided into three levels: independent, instructional, and frustration. In second grade, during the 3-month study, the average reading fluency increased significantly at a rate considered normal for that same period of time. Figure 2 showed the average growth of first grade students and Figure 3 showed the average growth for second grade students.

| Figure 3. 2nd grade Reading Fluency |

4.3. Mathematics

- Students’ ability to learn basic mathematical skills as it related to the content standards also increased significantly. The math apps designed for the iPad clearly assisted in the success of learning math concepts. During this study, first grade standards addressed the following topics:• Number Sense 2.1: Students demonstrate the meaning of addition and subtraction and know the addition facts (sums to 20) and the corresponding subtraction facts and commit them to memory.• Number Sense 2.3: Students demonstrate the meaning of addition and subtraction and identify one more than, one less than, 10 more than, and 10 less than a given number.• Algebra and Functions 1.2: Students use number sentences with operational symbols and expressions to solve problems and understand the meaning of the symbols +, -, x, and =.Second grade standard addressed the following topics:• Number Sense 2.2: Students estimate, calculate, and solve problems involving addition and subtraction of two- and three-digit numbers and find the sum or difference of two whole numbers up to three digits long.• Number Sense 3.1: Students model and solve simple problems involving multiplication and division and use repeated addition, arrays, and counting by multiples to do multiplication.• Algebra and Functions 1.1: Students model, represent, and interpret number relationships to create and solve problems involving addition and subtraction and use the commutative and associative rules to simply mental calculations and to check results.As the teachers taught these standards, they addressed them by teaching students using both the iPad and traditional methods and measuring outcomes based on assessments. Both classes saw significant growth in all 3 standards using the iPads as opposed to traditional methods (see Tables 1 and 2). The scores in each table represented mean scores students received on assignments in class as it related to each of the three standards. Four assignments were used in each standard for both non-iPad and iPad lessons.

|

|

5. Conclusions

- There is no doubt that the use of the iPad in these two classrooms was engaging for the students in this study. At the time of the study, not one student owned an iPad (although many had iPods or parents had iPhones). While both teachers allowed time for students to be instructed in the use of the iPad (at the beginning of the year), it was quickly observed the students needed little or no instruction irrespective of whether they had used an iPad before. Many times, students knew more about the app [program] than either teacher.In my interviews with both Olivia and Katie, it was clear that to increase student engagement and to avoid some potential distractions, they both planned for activities and ways to effectively use the iPad in the classroom. They preloaded apps on student iPads. Both teachers used iBooks with selected stories for students to read which allowed them to assign reading groups for certain books and, in turn, group students together based on reading levels. Olivia stated, “My little first graders had trouble at first but once we learned the rules, they really got into it. I even had some who were showing me how to do things. It was really cool to see them so engagement and getting better at reading and math.” She went on to say that she was amazed that her students improved as much as they did.Evidence showed that students in both grades increased in both reading fluency and math concepts over the course of the study. It was evident that students were more actively engaged during the iPad lessons than the non-iPad lessons. Albeit the some students did not increase as much as other students, the overall average was still significantly better with the iPad lessons and assessments. During the lesson observations, there were times when the iPad was a distraction to the lesson. This may attribute to the grade level and age of the students in this study. However, the preplanning by Olivia and Katie was effective in limiting the distractions that could potentially cause disruption in either class. Katie was quoted as saying “It took me a long time to figure out that I needed to really plan for the use of the iPad in my lessons. I guess that comes with being a first-year teacher.” Prior planning was evident in the discussions with both teachers and both agreed that it made a difference in the lesson outcome.Student learningThrough classroom observations and interviews, evidence showed the positive role that the iPad could play in the classroom. In early lessons that did not necessarily require the use of an iPad, both teachers allowed students to use the iPad voluntarily in order to explore some aspects of the concepts of reading or math in order to help understand. However, as both teachers became more involved with the use of iPads, then students were required to use them more consistently. The fact that the class was using the iPad also facilitated students assisting each other in the learning process. Throughout the class activities the students were fully engaged and did not stray to other iPad applications.In Olivia’s first grade class and Katie’s second grade class, the quantitative tests did not produce much indication of statistically significant change, yet there were interesting indications of possible trends. For example, student learning in first grade produced a large number of variables that impacted their engagement in the classroom, which in turn could account for the increase in student learning. As stated, at times, the iPad created some distractions but the increase in comprehension and application of the concepts in Language Arts and Mathematics outweighed those distractions.Both Olivia and Katie stated that one of the most challenging aspects of using iPads in the classroom and making part of everyday lessons was finding the time to locate appropriate apps for their respective grade levels. Both felt that this would be a continued challenge for them, but realized as more apps became available and as they continued in the teaching profession. However, having seen the increases in reading fluency and math concepts, the extra time spent on learning the information on the iPads was worth it in the long run.ConclusionsThrough it all, both teachers felt compelled to continue working with the iPads as they saw students become more engaged and “blossom” into deeper thinkers at a young age. Both teachers also agreed that the use of technology did not always equate to success for every student nor did always work for every student. Some students continued to be behavior problems; thus, they lost iPad privileges. Providing the devices in class and turning them on has never automatically made a difference in the lives of students. Prior planning was necessary.It was important to note that both Olivia and Katie felt that all this technology in the classroom was great, but two things did not happen. First, administrators did not provide professional development with the new iPads. Both teachers had to learn it on their own. Second, and more important, the school did not have the infrastructure for wireless connectivity, as was only discovered after iPads were purchased and students started using them. Wireless connectivity was constantly an issue. Katie said that the school “put the cart before the horse” and did not plan accordingly. The wireless infrastructure was not powerful enough to connect the entire class of iPads at one time. Therefore, Olivia and Katie needed to coordinate the use of iPads so that both classes were not using them at the same time.The iPad is essentially a device for an individual. Both Olivia and Katie found many issues around having a classroom set of iPads. Synchronizing content, having money to purchase apps, or charging a set of iPads was a seemingly constant issue. Overall, the increase in student engagement and the progression of student learning outweighed some of the more administrative challenges.iPad based learning will and cannot be the best suited learning devices for every student and learner, and there is the potential issue surrounding the costs to districts (especially in California where education funding is constantly cut). Further work in this area should continue as technology continues to advance at a rapid pace. Technology is simply another learning modality that, as teachers, we must learn to utilize in the classroom in order to reach some of the students that, for the most part, learn best in this type of format. As teachers, we need to promote and value students creatively experimenting in their learning and if the use of the iPad is a way to express that, then we need to embrace that as well.

References

| [1] | Banister, S. “Integrating the iPod Touch in K-12 Education: Visions and Vices”, Computers in the schools, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 121-131. 2010. |

| [2] | Corio, J. “Reading Comprehension on the Internet: Expanding Our Understanding of Reading Comprehension to Encompass New Literacies”, The Reading Teacher, vol. 56, pp. 458-464, 2003 |

| [3] | Dede, C. “Planning for Neomillennial Learning Styles”, Educause Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 7-12, 2005. |

| [4] | Frohberg, D., Goth, C., & Schwabe, G. “Mobile Learning Projects--A Critical Analysis of the State of the Art”, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, vol. 25, pp. 307-331, 2009. |

| [5] | Online Available: http://epicpolicy.org/publication/ realities-K-12-virtual-education |

| [6] | Holcomb, Sabrna. Teaching With Technology. 1st ed. National Education Association of the United States, 1999. |

| [7] | Oblinger, D. “Understanding New Students”, Educause Review (July/August), vol. 37-47, 2003. |

| [8] | Pflaum, William D. The Technology Fix: The Promise and Reality of Computers in Our Schools. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2004. |

| [9] | RAND Reading Study group. “Reading for Understanding: Toward an R&D Program in Reading Comprehension”, Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2002. |

| [10] | Sandholtz, J. H., Ringstaff, C, and Dwyer, D. “Teaching with Technology: Creating Student-centered Classrooms”, Teachers College Press: New York, 1997. |

| [11] | Sheppard, D. “Reading with iPads: The Difference Makes a Difference”, Education Today, vol. 3, pp. 12-15, 2011. |

| [12] | Sutherland-Smit, W. “Weaving the Literacy Web: Changes in Reading from Page to Screen.” The Reading Teacher, vol. 55, pp. 662-669, 2002. |

| [13] | Tomei, Lawrence A. Teaching Digitally: A Guide for Integrating Technology into the Classroom. 1st ed. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon Publishers, Inc, 2001. |

| [14] | Waters, J. K. “Enter the iPad (or not?).” The Journal : Technological Horizons in Education, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 38-45, 2010. |

| [15] | Yang, J. C. & Lin, Y. L. “Development and Evaluation of an Interactive Mobile Learning Environment with Shared Display Groupware”, Educational Technology & Society, vol. 13, pp. 195-207, 2010. |

| [16] | Zhao, Y., & Frank, K. “Factors Affecting Technology Uses in Schools: An Ecological Perspective”, American Educational Research Association, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 807-840, 2003. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML