-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2012; 2(3): 30-36

doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20120203.02

The Effect of Gender on the Patterns of Classroom Interaction

Nasser Rashidi , Sahar Naderi

Shiraz University

Correspondence to: Nasser Rashidi , Shiraz University.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of the present study is to explore the effect of gender on the patterns of classroom interactions between teachers and students in Iranian EFL classrooms. Twenty four classes were observed, recorded and the transcripts were produced. Frequency and percentage of discourse acts produced by male and female teachers on one hand, and male and female students on the other hand, were computed and compared with each other. Chi-square tests were run to diagnose the significant differences. According to the results of the study, although males and females shared some features, the patterns of teacher-student interactions were gender related. Female teachers were more interactive, supportive and patient with their students than male teachers. They asked more referential questions, gave more compliments and used less directive forms. On the other hand, the patterns of Student-Teacher Talk were also affected by the gender of students. While male students initiated more exchanges with their teachers, female students preferred to be addressed by their teachers. Male students also made more humor and gave more feedback to their teachers.

Keywords: Gender, Classroom Interaction, Gender-Related Classroom Discourse

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It has been generally assumed that gender is an affecting factor in the process of teacher/student interactions in the classroom. In other words, gender of both teachers and students influences the quality and the quantity of the interactions in the classroom. The research published from the 1960s to the 1990s indicated that teachers' treatment toward male and female students in pre-college and college level classrooms is unequal (Sadker & Sadker, 1992; Tannen, 1991). Actually, college teachers have been found to ask male students higher-order questions demanding critical thought (Sadker & Sadker, 1992), make eye contacts more frequently with males than with females (Thorne, 1979), allow their classrooms to be male-dominated by calling on males more frequently (Thorne, 1979), allow males to interrupt females (Hall, 1982), and respond to males with attention and females with diffidence (Hall, 1982). Teachers of both genders also frequently give male students more interaction time than female students (Sadker & Sadker, 1992), and initiate more contact with male students than with female students. As Sadker (1999) said, Classroom interactions between teachers and students put males in the spotlight, and relegate females to the sidelines, or to invisibility.Besides, carrying out a meta-analysis of 81 studies on gender differences in teacher-student interaction, Kelly (1988) concluded that teachers tended to interact more with boys than girls both in teacher and student initiated interaction. Teachers asked boys much more questions and provided them more response opportunities. In other words, Kelly came to this result that teachers totally pay more attention to boys than girls and this fact exist in a wide range of classroom contexts including EFL & ESL. Consistent with the most of the obtained results, Dale Spender (1982) also found her classroom interactions gender-biased since she was spending a minimum of 58% of her classroom time interacting with boys and a maximum of 42%, and an average of 38%, of her time interacting with girls.Gender of the teacher also affects the classroom environment (Canada and Pringle, 1995; Hopf and Hatzichristoo, 1999; Duffy, et.al. 2002). According to the studies that have been done in this area, teachers of different gender have classes with different characteristics. For example, the general characteristics of a class taught by a male teacher were faster-paced, much (excessive) teacher floor time, sudden topic shifts, and shorter but more frequent student turns. Similarly, female teachers were described as communicative facilitators and perhaps more tolerant of first language use. Female teachers were also described as too forceful in choosing topics and asking too many questions primarily with the intent to smooth and perpetuate the conversational flow (Chavez, 2000).In spite of all these differences among female and male teachers' behaviors in the classroom, Doray (2005) and Rashidi and Rafiee Rad (2010), in their studies of classroom interaction in Australia and Iran, respectively, revealed that male and female teachers had a lot in common in their patterns of classroom discourse supporting the notion that the choice of discourse feature was dependent firstly on the context and secondly on the role of interaction vis-à-vis each other in the community of practice.Male and female students were also different from each other regarding their patterns of interactions with their teachers. For example, most of the studies, whether they have been made in the far past such as Meece (1987) or done more recently like Francis (2004) have indicated that boys contribute more to classroom interaction than girls. It has been, actually, argued that teachers may interact more with male students because male students respond to and initiate conversation with their teachers more than female students (Meece, 1987). Put it in another way, since male students interact more in the classroom, teachers are caused to make interaction more with male students rather than female students (Duffy, et.al. 2002). As Rashidi and Rafiee Rad (2010) observed in Iranian context, boys were more likely to interact with their teachers. Male students, however, tended to be volunteer to answer the questions, even if they do not know the right answer. Similarly, they report being more likely to take longer turns.Nevertheless, Chavez (2000) found that female students tended to use humor less than males. Female students were more concerned with pleasing the teacher or meeting expectations. Female students reported taking shorter (more fragmentary) turns, but being more likely to be addressed in complete sentences by the teacher. On the whole, teachers and female students seem to form stronger cooperative units than teachers and male students: teachers were reported to be more likely to call on female students; female students more than their male peers enjoyed interaction with the teacher and took notes of the teacher's presentation. Putting all these studies together, however, it is not very clear to what extent gender affects classroom interaction as there are some controversies among the results of the studies. While some studies have illustrated that male and female teachers do act similarly in their classes and even the gender of their students does not affect their methods of teaching and their behavior in their classes, there are many others that emphasized the many discriminations that have been caused by the gender of both students and teachers. These discriminations and biases, indeed, can impress the quality of teaching and learning either in a positive way or a negative way. In addition, since the matter of gender has been considered differently in different countries and people from different cultures have different views toward it, the results of the studies in other cultures cannot be generalized to other contexts especially to an Islamic context like Iran where the gender has an essential role in social issues. Therefore more studies in this area are needed in order to make the situation clearer.As a result, the objective of the present study is to analyze classroom discourse in Iranian EFL classrooms by examining the effect of gender, both students' and teachers', on the patterns of interaction occurred in the classes. The questions are: 1. In their interactions with their students, are male and female teachers different from each other? 2. How are the patterns of classroom interactions (Student-Teacher Talk) affected by the gender of students?3. Is classroom discourse a gender-related phenomenon?

2. Methodology

2.1. The Participants

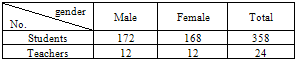

- 24 teachers and their 358 students in 24 classes in Bahar Institute took part in this study. Twelve teachers were male and twelve teachers were female. Classes were either single-gendered or mixed gendered. Eight of single-gendered classes were for boys which were taught by male teachers. The other eight classes were for girls which were conducted by female teachers. The other eight classes were mixed- gendered; four males and four females taught the classes. Students were considered as adult learners of the language ranging from 16 to 48. Availability was the main criteria of subject selection. However, classes were chosen in a way that equal number of single-gendered and mixed-gendered classes took part in the study.

|

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

- The process of data collection was comprised of two steps. The first step included the observation of classes and tape-recording the classroom conversations in which the researcher was present as a non-participant observer. Totally, 27 classes were observed and audio-taped. Each class lasted about 105 minutes. However, for data analysis, among the 27 recorded classes, 24 classes were chosen according to their degree of clarity and relevance. This means that three classes were left out of analysis since their qualities were not sufficient enough to be used in the study. Transcribing the collected data was the second step. Consequently, about 2520 minutes (42 hours) of classroom interaction were transcribed. Afterwards, three classes (10% of the whole data) were codified by the researcher. These three classes were chosen randomly. After two weeks, the same data were coded again by the researcher herself. Using a correlational analysis, the intra-coder reliability of the transcribed data was calculated (r=.991).

2.4. Data Analysis Procedure

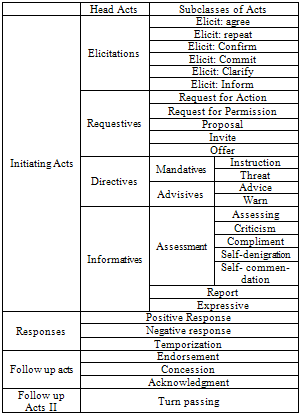

- Tsui’s (1994) framework was used as the theoretical framework of this study. Focusing on the linguistic features of conversation in relation to the context of situation in which the language is used, Tsui uses the criteria of “structural location” and “prospected response” and the concepts of act, move and exchange following Sinclair and Coulthard (1975) to analyze English conversation.

|

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. The effect of gender on the patterns of Teacher-Student Interactions

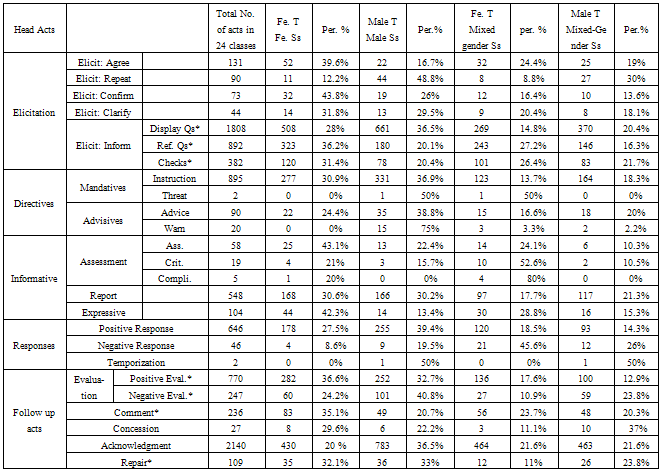

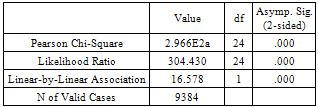

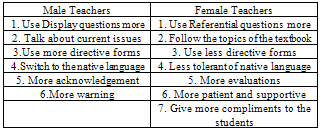

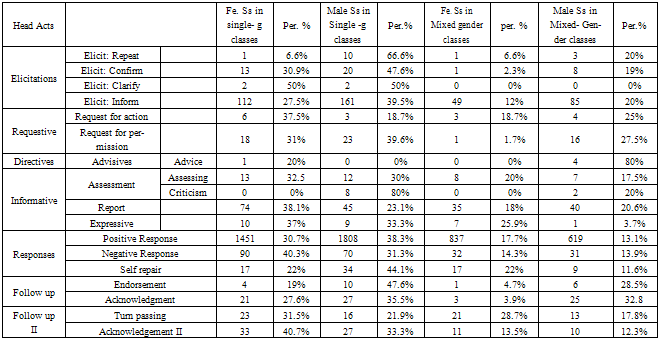

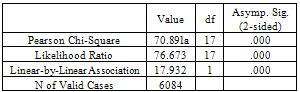

- As mentioned in the previous part, the frequency and percentage of each act produced by male and female teachers were counted and computed. The obtained results are reported in Table 3.1. It is important to know that the frequency and percentage of acts produced by 12 female teachers in single-gender and mixed-gender classes together were compared with the frequency and percentage of acts occurred in male teachers’ talks in the other 12 classes. According to the above table, regarding the use of some acts such as ‘Elicit: confirm’, ‘repot’, ‘positive and negative response’, male and female teachers were somehow the same. However, there were some differences between male and female teachers in using some specific acts. For example, male teachers showed preference to the act of ‘Elicit: Repeat’. Actually, about 78% of all ‘Elicit: Repeats’ occurred by male teachers while female teachers only used about 20% of all ‘Elicit: repeats’. There was also a difference between the occurrence of display and referential questions. While male teachers preferred to use more display questions (About 57% of all display questions), females employed more referential questions ( 63.4% of all referential questions) in order to interact with their students. By and large, female teachers were more interactive with their students and tried to encourage their students to talk and interact with other students by assigning different peer/group-work activities. Female students were also more interested in those activities than their male peers. Using many display questions made shorter but more frequent exchanges between teacher and students, one of the characteristics of classes taught by male teachers in our study. This is the feature that Chavez (2000) also used to describe the classes conducted by male teachers. Regarding the instructions, male teachers used more directives (55.2%) than their female peers (44.6%). Although female teachers used directives as well, most of the directives produced by them were in the form of requestives. Their motivation is surely Politeness. Generally speaking, girls and women tend to favor more polite and less direct forms of directives than males (Holmes, 1992). Another category which was used by males very frequently was warning. In fact, more than 77% of warnings in the classrooms were produced by male teachers. In addition, males did not give compliments to their students. Actually, no instances of compliments were found in the interactions between male teachers and their students (0%). On the other hand, female teachers made use of compliments and expressives more frequently. By giving compliments to their students, female teachers tried to make a rapport with their students in their classes. It is interesting to know that female teachers gave their compliments only to female students. Due to Iranian culture, it is not very common that a woman gives compliment to the opposite sex or vice versa. While, females tried to give feedback to their students in the form of positive evaluations (54.2% of all positive evaluations), males preferred to provide their students with acknowledgements (about 58% of all acknowledgements). Rashidi and Rafiee Rad (2010) also indicated that female teachers were more supportive than male teachers since they gave more positive feedbacks to the students.All these differences between the use of discourse acts by male and female teachers can lead us to conclude that male and female teachers had classes with different characteristics and there was a difference in their patterns of interaction with their students. In order to find whether this difference was statistically significant, a Chi-square test was run which investigated the association between teachers' gender and their use of discourse acts.In this case, the reported significant value is .000(p<.05). This means that the portion of discourse acts used by male teachers was significantly different from the portion of discourse acts used by female teachers. As a case in point, there was a significant difference between the number of positive evaluations given to the students by male and female teachers.In sum, taking into consideration the results of the study done on the relationship between teacher's gender and Teacher-Student interaction, we came to this conclusion that the difference in Teacher-Student interaction between male and female teachers is not accidentally significant. Patterns of teacher-student talk are gender-related and teachers with different gender have different behaviors in their classes. These results are consistent with findings of Canada and Pringle (1995), Chavez (2000), Hopf and Hatzichristoo (1988), Sadker and sadker (1992) and Tannen (1991). However, this is in contrast to what Doray (2005) and Rashidi and Rafee Rad (2010) found. Some of the features shared by male and female teachers are summarized in Table 4.11.

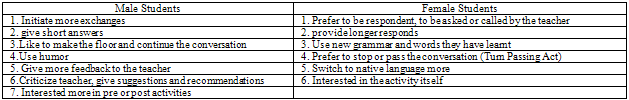

3.2. The Effect of Gender on the Patterns of Student-Teacher Talk

- In addition to the studies that investigated the way teachers with different genders interact with their students, there were some other studies which explored the impact of gender on learners' behavior in the classrooms. Most of these studies have indicated that female and male students have different patterns of interaction in classrooms (Chavez, 2000).At first, it should be mentioned that in all classes, only the number of responses that each student gave to the teacher was counted. In other words, the responses that were given by the whole class to the teachers were not counted.

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- In sum, taking into consideration the results of the study done on the relationship between teacher's gender and Teacher-Student interaction, we came to this conclusion that patterns of Teacher-Student talk are gender-related and male and female teachers have different behaviors in their classes. While male teachers used many display questions, female teachers asked more referential questions. Female teachers were more interactive with their students either in single-gender or mixed-gender classes. In mixed gender classes, male teachers were more interactive with boys than girls. These findings were supported by the findings of Thorne (1979) and Sadker & Sadker (1992). Female teachers were also more supportive and patient. They gave more compliments to their students and used less directive forms. Therefore, gender affects the Teacher-Student interaction. Other researchers who found classroom interactions gender-related are Canada and Pringle (1995), Francis (2004), Hopf and Hatzichristoo (1999), Kelly (1988) and Shomoosi et.al (2008). The result of the study is, however, inconsistent with the result of Rashidi and Rafiee Rad's (2010). The reason may be that her study investigated only single-gender classes while this study works on both single and mixed- gender classes.The difference between male and female students' utterances in the classroom is also significant. This means that the patterns of student-teacher talk are affected by the gender of students and students with different gender interact with their teachers in different ways (Chavez, 2000). In mixed-gender classes, male students initiated more exchanges with their teachers, made more humor and gave more feedback to their teachers. Consistent with the results of Shomoossi, et.al.’s study (2008), our study also indicated that pupils play an active part in bringing the gender differences in classroominteraction into being: boys are more likely than girls to create conditionswhere their contributions will be sought by teachers, and they are morelikely than girls to push themselves forward when contributors are notexplicitly selected. However, this is not to say that teachers are entirelypassive in the process (Shomoossi, et.al. 2008, p. 180)Of course, gender cannot be the only factor influencing classroom interaction. As Tannen (1996b) said, classroom interaction might be affected by a group of factors such as race, class context, and age differences along with sexual orientation, professional training, and individual personality. However, although it is difficult, we should try to eliminate the discriminations that are caused by gender in our classes. As Jones (2000) has found, fortunately, unequal treatment of girls and boys can be decreased through training and self-analysis of video recordings of classroom teaching.

5. Conclusions

- In sum, analyzing the classroom discourse according to the gender of students and teachers, we found that 1. In their interactions with their students, are male and female teachers different from each other? Yes. According to the results of the study, male and female teachers are different from each other while they interact with their students. In other words, there is a great difference between the behavior of men and women (teachers) in the classrooms. To give some examples, male teachers used many display questions but female teachers asked more referential questions which promoted more interactions between the students and the teacher. Female teachers were more interactive with their students both in single-gender and mixed-gender classes; they encouraged different interactive tasks such as peer and group works in their classes. Female teachers were also more supportive and patient. They gave more compliments to their students and used less directive forms. Other researchers who found classroom interactions gender-related are Canada and Pringle (1995), Hopf and Hatzichristoo (1999) and Kelly (1988). 2. How are the patterns of classroom interactions (Student-Teacher Talk) affected by the gender of students?Based on the obtained results, the difference between male and female students' utterances in the classroom was also significant. This means that the patterns of Student-Teacher Talk were also affected by the gender of students (Chavez, 2000). In mixed-gender classes, male students initiated more exchanges with their teachers, made more humor and gave more feedback to their teachers.3. Is classroom discourse a gender-related phenomenon?All in all, we came to this conclusion that classroom discourse is gender-related to some extent (Shomoosi, et.al. 2008). In other words, gender plays an important role in the way the participants of a classroom interact with each other. However, according to Tannen (1996), gender cannot be the only factor influencing classroom discourse. Context of the classroom, students’ and teachers’ age, teachers’ experiences and other individual personalities may have considerable influences.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML