-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2012; 2(1): 35-40

doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20120201.07

Psychological Assessment of Visual Impaired Children in Integrated and Special Schools

Kasomo Daniel

Department of Religion Theology and Philosophy in Maseno University Kenya & Faculty of Psychology, St. James the Elder Theological Seminary, Jacksonville, Florida, USA

Correspondence to: Kasomo Daniel , Department of Religion Theology and Philosophy in Maseno University Kenya & Faculty of Psychology, St. James the Elder Theological Seminary, Jacksonville, Florida, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Although the educational services for children with visual impairment in Kenya have expanded to include provision in the integrated school setting, not much research has been done to document the benefits of the integrated programme to the children involved. The researcher used the ex – post – facto design to compare the self – concept of 20 blind children in classes 5 to 7 who had been placed in integrated (N = 10) and special (N = 10) schools. Self – concept was measured with a self – concept scale developed by the researchers based on existing self – concept scales especially, the Piers – Harris Children’s Self – Concept Scale and the Tennessee Self – concept Scale. Other variables examined were pupil to pupil and teacher to pupil interaction. The data were analyzed using the two – tailed t – test. The blind pupils in integrated schools had a significantly higher (t = 2.08, p<, 0.5) self – concept than their counterparts in special schools. The level of pupil to pupil interaction for the blind pupils in integrated schools was significantly higher (t = 2.97, p<.01) than that of pupils in special schools. From this finding, it was concluded that the integrated school offers a social environment favourable for the development of a positive self – concept. However, more research involving a larger number of blind children should be carried out to come up with more definitive findings. Integration of more blind children and children with other disabilities, which should be preceded by provision of supportive services and facilities, was recommended.

Keywords: Blind, Children, Integrated, School

Cite this paper: Kasomo Daniel , "Psychological Assessment of Visual Impaired Children in Integrated and Special Schools", Education, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2012, pp. 35-40. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20120201.07.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Over the past years, there has been an increase in the enrolment of children who are disabled in Kenyan ordinary schools due to the shortage of special schools and the current trend towards educating these children in a normal and less restrictive environment. Statistics of 1995 show that about 15% (12,000) of the 80,000 cases of handicapped children identified countrywide through the Educational Assessment and Resource Centers could be accommodated in special institutions (Njoka, 1996). According to the 1989 Government census, 251,713 people had disabilities out of which 24% (60,411) were visually impaired. Out of the big population of handicapped children, only about 26, 885 could be catered for in the special primary schools, special secondary schools and technical and vocational institutions in the country (Ministry of Education, 2004). Very few visually impaired or in the 1,100 integrated special units in ordinary schools. Exact figures on the blind pupils were not readily available during the study, but the number is bound to be low because these programmes have mainly targeted childrenwith low vision. Again, many regular schools lack adequate facilities that are necessary in meeting the needs of blind children. Research in this area was necessitated by the fact that segregation into a special school or placement into an ordinary school, which are two distinct social environments, may affect the development of the children involved differently. This study singled out one aspect of development, that is, the development of self – concept. Research conducted in this specific area is not conclusive and the few studies (Sharma & Mittal, 2004; Scolor & Mittal, 2004) available have been conducted in other countries. Placement of children who are blind in ordinary schools alongside their unimpaired peers may make them develop a positive self – concept, feel accepted and prepare them for adult life and societal integration. On the contrary, if these children are not accepted and recognized or if they are discriminated upon by teachers and pupils in the ordinary schools, they may fail to develop a positive self – concept. Hence, there was need to investigate how placement affects the way the child perceives himself/herself. The main purpose of this study was to investigate whether school placement influences the self – concept of children who are blind. The other aim of the study \was to find out whether there is a difference between the levels of pupil to pupil and teacher to pupil interaction of blind children placed in ordinary and those placed in special schools. It was hypothesized that placement would not differentially affect the self – concept of children who are blind. The level of pupil to pupil and teacher to pupil interaction was expected to be different for the two groups under study. The present research was expected to fill in the gap in knowledge in this specific area by showing how placement in an ordinary school may or may not give the blind child an advantage in the development of a positive self – concept. It was anticipated that the study would create more understanding of self – concept by showing how it is influenced by integration. The study was also expected to validate previous findings of research done in other countries on the relationship between integration and self – concept, stimulate interest for more research on the studied variable and other factors that are likely to cause disparities in self – concept among children with disabilities and come up with suggestions on how to enhance the development of a positive self – concept.

2. Literature Review

- Self – concept is the way an individual perceives himself/ herself. It includes the person’s ideas of the kind of person he/she is, the characteristics he/she possesses and his/her most important striking characteristics (Coopersmith & Fieldman, 1974). Zahran (1967: 225) comprehensively defined self – concept as:An organized, learned, cognitive and unitary configuration of conscious perceptions, conceptions and evaluations by the individual, of his self as he actually is (Perceived – self), as others are supposed to see him (other – self), and as he would most like to be (ideal – self). A number of theories have been advanced in an attempt to explain how self – concept develops. The interactionist theory of self – concept mainly emphasizes the role of the society and the persons with whom the individual interacts with in determining his/her self – concept (Gordon, 1972; Maritim, 1979). The cognitive theory emphasizes that mental maturation attained as the child progresses through various cognitive stages and social experiences facilities the development of self – concept (Piaget, 1967; Bem, 1972; Horrocks & Jackson, 1972). According to this theory, the child’s self – concept will start to stabilize when he/she becomes cognitively mature, that is, from the age of 12 years onwards. Moeller (1994) disagrees with this view, arguing that self – concept stabilizes much earlier than the onset of the adolescence stage. The ecological theory views self – concept as a function of three factors, that is, others, environments and things that provide, mediate and perpetuate social experiences (Hormuth, 1990). Self – concept develops through social experiences that take place in a context of interaction with others (as the source of direct social experiences),;objects (as symbols and representations of social experiences), and environments (as settings of social experiences). According to Hormuth, a change of this ecology will result in change in self – concept to match the demands of the new set – up. Ordinary and special schools provide children who are blind with two different settings in terms of environment, others, social experiences and facilities – differences that could be reflected in the way they perceive themselves. Integration implies the participation of children who are handicapped in curricular, social and extra – curricular activities in the general education school. In an attempt to rationalize the need for integration, proponents argue that the dual system of education encourages stigmatization, unnecessary competition and duplication of limited resources (Stainback & Stainback, 1980, 1984; Telford & Sawrey, 1981; National Research Centre on Learning Disabilities, 2005). The various proponents point out that, instructional methods, strategies of accommodating and dealing with individual differences and curriculum do not vary with the system of education. Thus, with proper planning and provision of the necessary facilities children with handicaps can easily be accommodated in ordinary schools. However, Chapman (1988) considers the placement of students with special needs into regular classrooms without changing the regular education system and without providing professional support services as “main dumping”. This can be avoided by developing policies to ensure instructional and organizational changes are made in the mainstream to facilitate the educational normalization of students with special needs. A positive relationship has been reported between integration of children with various types of disabilities and variables such as self – confidence, self – image, maturity, self – esteem, independence, special academic skills (for example, problem solving and language comprehension and usage), acceptance of individual differences, change of teachers’ attitudes towards integration, development of copying and adaptive skills, and social and emotional development (Hegarty et al., 1981; Tutle, 1987; Giangreco et al., 1993; Salisbury et al., 1993; Janney et al., 1995; Scholar & Mittal, 2004; National Research Centre on Learning Disabilities, 2005). These findings show that integration may have a positive effect on the way the child perceives himself/ herself. However, integration may not guarantee acceptance of children with disabilities by the non – disabled (Jones et al., 1972; Goodman et al., 1972; Iano et al., 1974; Levitt & Cohen, 1976). Rejection by peers may have a negative effect on the development of the self concept of the child who is disabled. A study of 104 (60 boys and 44 girls) by Sharma and Mittal (2002) showed no differences in global self – concept between children in integrated and special school settings. However, the two groups differed significantly in the social and temperament dimensions of self – concept. Scholor and Mittal (2004) found no gender differences in the academic skills of visually impaired children in special and integrated school settings. In another study of 211 preadolescents with mild intellectual disabilities, Marsh et al. (2006) found those in segregated classes to have self – concept than those in regular c\lasses. The differences were in academic self – concept, peer relations and global self – esteem and not in physical appearance and parent relationships components of self – concept. Similar mixed results are reported in another study by Lopez – Justicia et al. (2005) in which children with congenital low vision (N = 17) scored lower than their normal vision peers (N = 17) in the aspect of self – concept to do with relationships with classmates but higher in relationships with parents. In the same study, no differences were found in other facets of self – concept, such as physical ability, physical appearance, verbal ability, mathematics or general subjects. The mentioned studies show mixed results and therefore the findings are inconclusive. Self – concept has been found to be related to various factors such as satisfaction with life, low anxiety, low aggression, academic achievement, educational level, motivation in performing certain skills, independence, risk taking, courage, leadership, analytical thinking, creativity and ability to express oneself, social interaction, attitudes towards science, and achievement of life goals (Rosenberg, 1985; Stangvik, 1979; Kershner, 1990; Lawrence, 1991; Beach et al., 1995; Wachanya et al., 2005). Thus, a person with a positive self – concept has an advantage over those who have a low self – concept. Integrated and special schools offer different opportunities for social interaction and social experiences. The blind child who is placed in an integrated school enjoys greater social interactions and experiences as compared to the child in the special school (Rukwaro, 2006). These interactions and experiences may have a positive effect on the way the child perceives himself/herself.

3. Methodology

- Participants: The subjects of study comprised 20 blind children in class 5 to 8 who were placed in integrated (N = 10) and special schools (N = 10). The 10 subjects from special schools were selected randomly from two special schools that were also drawn randomly from the 10 schools for the blind in Kenya. The other 10 were from four districts (Kisumu, Naruku, Homa Bay, and Nairobi) that were randomly selected from the 19 districts in which the integrated programmes for children with visual handicaps are in operation. Integrated programmes for children with visual impairments have mainly targeted children with low vision; therefore, the number of blind children who could be accessed was not big. Measures: Self – concept was measured with a five – point Likert – type scale developed by the researchers using other existing self – concept scales, especially the Piers- Harris Children’s Self – concept Scale and the Tennessee Self – concept Scale. It comprised of 80 items and had a reliability correlation coefficient of 94 established through the split – half method of estimating the reliability of an instrument. This reliability was established through a pilot study and was considered to be sufficient. Pupil to pupil and teacher to pupil interaction was measured with self – report scales developed by the researchers to assess the level of interaction among pupils and between pupils and teachers. Both scales comprised 16 items each and had split – half correlation coefficient reliabilities of .67 and .78 respectively which are within the acceptable level of .70 (Selltiz et al., 1996).Procedure: Due to the subjects’ visual impairments, the researchers read through the items in the three questionnaires together with the respondents and allowed them time to give their responses. The respondents were handled individually and responses were recorded for them. The two – tailed t – test was used to analyze the data.

5. Results

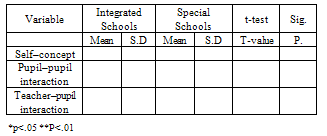

- The self – concept of blind children placed in integrated schools was found to be significantly higher (t = 2.08, p<.05) than that of blind children placed in special schools. The level of pupil to pupil interaction for the blind children in integrated schools was significantly higher (t = 2.97, p<.01) than that of their counterparts in special schools. There was no difference between the level of teacher to pupil interaction of blind pupils in integrated and special schools.

|

6. Discussion

- It is possible for the blind child who is placed in a special school to feel that he/she is being treated differently because of his/her impaired vision and see and rate himself/herself as being different from other children. The blind child in a boarding special school has limited opportunities for interacting with other people such as parents, adults and unimpaired children during the school term. This may have a negative effect on the development of his/her self – concept considering that social interactions are crucial in the formation of self – concept. Most of the partially sighted children who are the majority in special schools may choose to interact among themselves leaving out the totally blind child. This may make the child to feel isolated, unaccepted, unwanted, and this may have a negative impact on his/her self – concept. On the other hand, the blind child in the integrated environment has an advantage of interacting with many sighted children and adults. As a result of this interaction, he/she may not think or evaluate himself/herself as being different, he/she may not think or evaluate himself/herself as being different from other people. This is perhaps why blind children in integrated schools tended to have a significantly higher self – concept than those in special schools. When the blind is placed in a special school and treated with sympathy he/she may perceive it as an admission that he/she is different from other children and this may lower his/her self – concept. The blind child needs friends and a family that accept him/her so as to develop a positive feeling about himself/herself. Moving the blind child into special school away from the family at an early age may be understood to mean that he/she is not an important and a wanted member of the family and hence the apparent low self – concept. On the other hand, the self – concept of the blind child in the integrated environment may not be negatively affected if the people around him/her treat him/her positively and with care and love. This could be the case with the blind child in the integrated school environment. According to Tutle (1984), lack of sight makes the simplest daily tasks difficult or impossible and may cause a devaluation of self, and the pity shown by well meaning people reinforces the lowered self – esteem. The self – esteem of the blind child could be lowered further by placing him/her in a special school where he/she only interacts with children who have a similar impairment. When children are identified as being visually impaired they are placed in their home schools without caring about whether the schools are adequately prepared for them or not. Most of these schools may not have a single teacher trained in special education and lack adequate facilities or may not be in any way prepared to accommodate the special needs of the child. The blind child in these schools relies on the programme coordinators who visit children in the programme occasionally to help and access their special needs. As observed during the research in some of the areas, the coordinators visit these children once in a month or once in a school term (that is, once in three months). Given the shortcomings inherent in ordinary schools, these children will definitely face difficulties in their day to day operations. If these children are not helped out of these difficulties they may feel neglected and unwanted. Such feelings will impact negatively on their self – concept. According to Hammachek (1971), self – concept can develop from a feeling of belonging, worthiness and competency. The individual needs to feel liked, cared for, and being recognized as a unique person. Recognition of what the child can do may tend to enhance his/her self – confidence and eventually his/her self – concept. This may be lacking in integrated schools where the class teachers are dealing with large numbers of children. This suggests that other factors apart from the attention of the class teachers are necessary for the development of a positive self – concept. In most developed countries integrated schools could be adequately equipped and prepared to take the challenges that go along with the integration of children with disabilities in ordinary schools. This may account for the gains reported in these countries in self – confidence, self – image, maturity, independence and self – esteem among other personality traits after integrating children with various disabilities in ordinary schools for a period of time (Hegarty et al., 1981; Giangreco et al., 1993; Salisbury et al., 1993; Janney et al., 1995; Scholor & Mittal, 2004; National Research Centre on Learning Disabilities, 2005).The totally blind child in the special school is likely to receive little concern and attention from fellow pupils who also have their own difficulties to think about. The teachers’ attention in these schools is focused on many blind pupils; therefore, the individual child possibly will not receive as much attention as the one in an integrated school. This is a possible explanation of the reported significant difference between the self – concept of blind children in integrated and special schools.

7. Conclusions

- The findings showed that placing blind children either in special or in ordinary schools affects their self – concept differently. The finding that blind children placed in ordinary schools tend to have a higher self – concept than those placed in special schools may not be definitive since the number of cases involved was small. The fact that public ordinary schools in Kenya generally seem not to be adequately prepared for integration led to the conclusion that some measures have to be taken to make the integrating school environment more conducive and accommodative for the integrated programmes to yield better results in terms of the child’s development. In addition to providing the basic learning resources, there is great need for training teachers in special education so as to equip them with the basic skills that can help them to identify the needs of the children involved and to be able to address those needs in an integrated environment. This could make the child feel accepted and consequently influence his/her self – concept positively. Integration of more blind children and children with other disabilities should be considered. This is because the findings suggested that the self – concept of blind children tend to improve after integration. However, this should be preceded by the provision of basic facilities.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML