-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

July, 2012;

doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20120001.06

Experimentalism in the Field Museum Education: an Empirical Reaserch on the School-Museum Relationship

Antonella Nuzzaci

Department of Human Sciences, University of L’Aquila, Abruzzo, Italy

Correspondence to: Antonella Nuzzaci , Department of Human Sciences, University of L’Aquila, Abruzzo, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of this research was to develop, test, evaluate and validate a model of guided tour with public school. The study covered the trial in a deeper and broader discourse on the relationship between school-museum. The research is part of a study that understands the enjoyment to the cultural heritage and museum as a cultural right to use goods essential to the growth of interpretative repertoires of the student, especially those who belong to low classes.

Keywords: Museum Education, Learning, Cultural Rights, School-Museum Relationship

Article Outline

1. School and Museum in the Logic of “Partnership”

- The growing interest developed in recent years around the study of the phenomena related to the link between school and cultural institutions has led the author to deal with the relationship between school and museum in order to try to shed light on certain aspects, wrongly, neglected by pedagogical literature.The underlying assumption moves from the awareness that a complex society such as the one we experience daily necessarily entails interdependence between individual and social changes in the context of teachers, causing them to change their professional behaviour. The focus of school on the museum or cultural good in a wider sense, established in Italy around the Seventies, has therefore led teachers to rethink the didactical work in relation to the evidence of human history as a further source of learning.It is obvious that in order to implement a real educational project, where the school works with the museum to enhance the learning of the museum good, it is necessary to establish partnerships and a mutual cooperation between the two institutions. For those who work in the area of education or museum didactics, the availability of updated data on the use of the museum as an educational resource cannot be considered as an ancillary and random activity, but it must rather be conceived as the fundamental way of working, a systematic educational practice to achieve an effective planning of the interventions.No one can deny the importance of the educational role that these two cultural institutions play within the society. In Italy, as indeed in the rest of the world, the number of museums continues to increase and international educational bodies insistently encourage the use of educational places outside school. Visits to the museums are directly and indirectly recommended even in primary and secondary school curricula. Although the number of museums that offer didactical services and products has increased, they still have not received any feedback from a scientific point of view, as until now there has not been an assessment of their quality. However, this situation is about to change as the problems currently encountered in the school system are pushing towards new ways of renovation of the school, a trend confirmed by the current reforms that attempt to create a system of integrated education. These two institutions can jointly strengthen their cooperation and establish a form of active “partnership” in order to promote the education of students[1;2]. Several studies propose it[3] and some research groups are trying to work in this direction by studying the process of professionalization of the museum from a didactical point of view, even placing it in relation with the renewal of the teaching function.On the other hand the efforts to formalize a school-museum relationship, even in Italy, have been fulfilled in a recent law on cultural heritage (No. 352 of 8th October 1997), which foresees in Article. 7 a Provision for the diffusion of knowledge, in schools, of the artistic, scientific and cultural heritage, the opportunity for schools to enter into agreements with the Superintencies, according to which museums are committed to provide specific didactical courses for school visits and to prepare material and audio-visual aids that take into account the particular needs of pupils, including those with disabilities. If this has been included in a recent article of law in a very concise way, besides translating this provision in an operational sense, it is necessary to study:● The cognitive impact of the visit, particularly with regard to the type of teaching that it is possible to achieve in terms of learning methods. ● The communication between teacher-pupil, teacher- expert, expert-pupil.● The set of strategies to enhance observation, attention and facilitate the teaching and learning path.Basically, it is necessary to increase the research able to shed light on the conditions favourable for a cognitive effect of the museum visit. This is probably apparent when you actually try to understand how and which learning conditions can be improved by different users, academic or otherwise, and when you try to distinguish a school situation from a non-school situation (formal and non-formal).The school-museum relationship clearly illustrates the advantages and obstacles required by educational cultural collaborations. Spontaneously, after a long time and in small numbers, activities of collaboration, either occasional or regular have been established between the two institutions on the basis of personal initiatives between teachers and museum directors. In practical terms, the relations established actually show, both for teachers and operators, a circumstantial and random collaboration, which cannot rely on the efficiency of the structures.This reveals the personal and professional need of a social re-contextualization of teaching, in particular of the need to establish “a territory of education and teaching”[4] common to museum and school, defined in terms of space of proximité and proxémie[5]. The first is characterized by an educational solidarity of those actors involved in the school system that enables students to participate in social experiences. The second corresponds to the cultural and family space of students and teachers and implies the existence of a relation of discontinuity with the continuous space, defined by the concept of proximity.We should therefore ask ourselves what are the relationships between museum and school, between museum and education. The matter seems naive but it reaffirms the need of a meeting between two worlds, within the framework of a new logic of “partnership”.The term “partnership” has established itself in the international arena and has been included in an "ideology of the consensus" and reconciliation between school and museum. The introduction of this term shows a change in the school's willingness to adapt to the evolution of society and leads to a rethinking of the educational practice. Until now, the two institutions have experienced parallel realities, related to different value systems, which brought them to differently interpret the social function of education. Each institution has developed its own professional culture and different access roads to the many disciplines. The current desire of openness is therefore set within the process of a normal evolution and gives life to a consensus that, apparently, has nothing extraordinary. The openness thus appears desirable, a certain value which seems to ease and partly correct the legislative closure. It is in fact produced by the sporadic initiative of the various actors (teachers and museum staff) that develop the opening of the system at a practical level. While school tries to react to the “cognitive conflict” determined today by the social demand of new knowledge, the museum attempts to actively participate to its own process of cultural identification to redeem the spatial and temporal immobility that has ruled for a long time.Actually, to talk about non-formal education only makes sense when considered in relation to an adult audience already educated, socialized and placed professionally. This means that the visit to the museum is generally conceived as a voluntary activity, which is done when you have time, without established programs and which does not require an assessment to certify the results of it. When we think of students brought to a museum by adults, the non-formal nature of this visit is more difficult to distinguish from other activities performed outside school, especially when some teachers – yet there are not many – are used to carry them out. Between the museum conceived as a resource, which claims and tolerates the presence of school groups accompanied by their teachers, and the educational services of the museum, which offer specific proposals addressed to different audiences, there is still a number of implications which should be considered.The observation of the museum-school relationship then leads to question about how the use of the museum is in relation to the professional activity of teachers. If one may say that the museum can be seen as a necessary teaching complement in the ordinary activity performed by the teacher in the classroom, it is equally true, however, that the use of this “tool” brings changes to the professional “practice” of teachers themselves, both because it refers to the construction of a new knowledge, asking the teacher the ability to operate across them, and because it determines the change of “form” and “nature” of the teaching proposal.The set of questions concerning the cultural-educational relationship between school and the museum then refers on one hand, to the change that drives today’s society, which forces the two systems (school and museum) to break with a sclerosing tradition that saw them in the past even more projected within themselves and, on the other hand, to the social will of both to enhance external resources recognizing an educational potential even outside their own area of responsibility. This valorisation can only be accompanied by a precise estimate of the skills to be acquired by all those who work in the two systems to stem the current fragmentation of knowledge that is being produced today. The relationship between school and museum is then set within a democratic dynamic of renewal, rather than in a school practice of complementary diffusion of knowledge and asks to be redefined according to the logics of action of the actors involved.The central issue is therefore to seek new ways of professionalization of the various parties involved in the above-mentioned “territory of education and training” in order to guarantee the necessary quality of learning, the consistency of the interventions and their adjustment to the personal as well as social demand, in a Life Long Learning perspective. Therefore, the will of the museum and the school to establish a strong partnership is part of a wider movement of re-composition of the society and of the value systems.Until now, in the museum context, those who have been involved in educational services have emphasized the cultural role of the museum referring to the term “mediation” which would lead to a contrast between the meaning of “cultural” and the one of “education”[6]. This is justified by the fact that great efforts are often made to provide a distinction between “museum practices” and “pedagogical practices”. It is worth noting that the rejection of the educational dimension, when it occurs, goes hand in hand with the revaluation of the cultural dimension, regarded as more prestigious and noble. This dual role of culture and education has a long history. In Western countries, after the creation of museums, the idea of the educational role has always been taken into account[7]. The museum has been defined as a place of memory of the nation, of conservation of objects and of cultural education for the population[8]. With regard to the current educational role of museums, in those countries where a more careful discussion about this topic has been carried out, the matter becomes clearer. Thus, the suggestion comes from Great Britain[9] and explains that the educational dimension must occupy the most important place in museum programs. Museums are encouraged to integrate education in all their activities. In the United States, however, the educational dimension of the museum is based on two principles: excellence and equity[10], which influence all actions taken by it. Museums shall embrace the cultural diversity of the American nation and their commitment to education should reflect the diversity of the society. In France, by contrast, the educational dimension of the debate on the relationship between the public and the museum is based on the term 'cultural', which seems to better correspond to the action that museums want to pursue, because the emphasis is placed on a cultural and mediation action that involves not only the school audience. In Italy, however, especially in the Nineties, the term “didactics of museums” is establishing itself, conceived in its broadest meaning of action aimed at all types of audiences.So the collaboration between school and museum conveys new meanings on how the society is expanding its definition of “education”, to describe a life long learning process, skills and characters that take place as soon as we enter in the classroom, but in a variety of formal and informal ways. However, museums and schools still have to work on common learning goals.In the reform movement, school has turned from the traditional paradigm of learning guided by the teacher and of disseminated knowledge, to a curriculum centred on the learner that promotes the development of the learning by the subject, who thinks critically, solves problems and works in a collaboratively way[11; 12; 13].The knowledge given by the museum, according to the most common opinion, seems to be different from that spread through the school system, as the former differs from the second because it is a particular “emotional” and not “exclusively cognitive” knowledge. Generally, in fact, school knowledge is often conceived outside school as a partial knowledge, which takes into account only part of the emotional dimension of the students. This conception is confirmed by some interviews carried out with figures involved in the teaching and museum fields, interviews carried out within the research that will be further below outlined.It means to go back in a circular fashion to the starting point, to the existence or not of a spirit of cooperation between school and museums, between museum professionals and teaching professionals, a cooperation that has educational purposes.The “educational vocation” established with the birth of museums shows exactly this concept, the past, although rare, forms of cooperation between teaching and museum staff, the hypothesis of a possible use of teachers in the educational services of the museum, the ministerial circulars that followed one another after 1990 until the most recent law of 1998 that formalizes the relationship between the two institutions, the set of educational-museum experiences currently underway – both in their negative and positive aspects – confirm the existence of a cultural and educational “interface” between schools and museums. The actions that have followed one another in the teaching and museum fields, despite their problems, suggest that the spirit of cooperation exists in different degrees, in a considerable part of the population.Thus, the meeting between school and museum operators takes many shapes, depending on the representation they both make of each other, of the objectives and expectations, more or less explicit, of the dominant values of each of them. Therefore, formal and non-formal education can either help or mutually inhibit each other depending on the attitude adopted by those operating in the systems.The existing ideology of “conservation” should now share its role of orientation with the new ideology of “collaboration”. This radical change is challenging, but not without risks. It means to deal with the complexity of the relationship between the conservation of the objects and their use in education. The challenge today is to preserve the traditional museum concepts, combining them with the educational values focused on how those objects present in the museum can add value to everybody’s quality of life[3].In this context, the research proposed below has given a significant contribution providing a first product that would meet the need of knowledge and support of all those involved in the production of new answers to better identify the issues related to the museum as a learning context, and in particular in the area of use of the demo-ethno- anthropological goods[3].It is clear that this work reflects the complexity of the variables involved and that the small number of research carried out, not only in Italy but also in other countries, defines its pioneering character; its importance is related precisely to the fact of turning, even only from a school - museum point of view, the debate from a merely argumentative to a logical / scientific level, although being aware of the implicit limitations that might arise and the risks related to the many variables involved; however, the judgments and assessments of learning conditions in the context of museums that are formulated in terms of "common sense" are equally perceived as limited and risky. This work is in some way a response to the need of renewal of the school and the museum, ancient cultural institutions that play their role meeting in the field of didactics, a didactic that involves the linking of factors that affects the production and transmission of knowledge. Teaching the importance of the museum not only involves cognitive processes, but it is also an activity that takes place in a context of social interaction culturally mediated by the relationships through which it is expressed, characterized also in a spatial and physical sense by the behaviours related to the objects and environments in which learning takes place. The area in which this study is placed it is all yet to be explored, therefore, all contributions going in this direction can be very important because once clarified, verified and recognized the role the museum plays for the school, i.e. as an “important instrument” in the process of education, it is necessary to begin to consider this relationship in a “stable and organic” way within the general framework of the Italian school.

2. The Study of the School-museum Relationship According to an Integrated Research Strategy

- The research aimed, in a first stage (exploratory), to study the issues related to the school-museum relationship, and in particular to understand the relationships between museum and education, between school and museum didactics, and, in a later stage (experimental), to study the learning and memory of the experience of the guided visit to a demo-ethno-anthropological museum: the National Museum of Arts and Popular Traditions of Rome. The aim of the study was to shed light not only on 'museum education' understood in a comprehensive way, but also on a field museum didactics. We can say without doubts that the educational offer in the museum field is a skill of intersection and as such it comes from the confluence of different disciplinary contributions[14], so it is actually more correct to talk about museums didactics, with the plural, or even better about a demo-ethno-anthropological museum didactics, a didactics of science museums etc.In the light of an integrated research strategy, during the observative stage we tried to grasp the implications of the difficult school-museum relationship and we carried out a survey, which involved:● The school – interviews to a sample of primary, secondary and high schools teachers operating in the City of Rome (12.000).● The museum – interviews to the directors of the demo-ethno-anthropological museums of the region Lazio and Toscana.● The register of professionals – interviews to those who perform a service of cultural and educational promotion or experts in the field who are directly or indirectly involved in the field of education and culture within the Lazio region: “intersection competences”[15].We have tried on one hand to describe the objectives and the types of museum educational programs and on the other hand, the terms and typical forms with which school approaches these latter.Museum didactics has been therefore seen according to a tripartite view, considering school as a user of the museum and protagonist of the museum coordination and valorisation initiative, and the museum as a provider of educational services, the “body of judges” as a set of privileged observers and co-authors of the quality of the didactical proposal. In particular, in a field museum didactics view, the exploration has foreseen the description of certain types and models of didactics specific of the demo-ethno-anthropological museums of Lazio and Toscana and of their use by teachers. Moreover, it has taken into account the professionals in the field who, directly or indirectly, affect the quality of the definition of the teaching proposal. This had the dual objective of meeting the information and interpretative needs of the school phenomenon (educational use of the museum at school) and of the museum phenomenon (demo-ethno- anthropological museum education) within a specific local context (the one of the city of Rome).In short, the results show how, even nowadays a largely inadequate role is reserved to the relationship between school and the complex of museum cultural evidence (artistic, historic, archaeological, demo-anthropological etc.), both for the potential of the museum and for the education needs of the student within different age groups. We are aware of the fact that the museum good is not perceived by school in its most natural dimension, i.e. first of all as the ability to derive enjoyment from the encounter with cultural objects. It follows that there are still educational strategies that lack to help the student to grow in this dimension, starting from the simplest experiences, towards more complex ones. It means that we do not recognize the importance of the museum as authentic educational context in which learning can be produced[16; 17; 18] and where “transformations of concepts” previously held by other subjects can take place. The acquisition of knowledge arising from the complex processing tasks of a learner, who compares his knowledge with new information, mobilizes and produces new meanings, which are best, suited to respond to the issues or topics learned.Although we generally attach a fundamental importance to the museum concerning its ability to put people in learning situations that have at the basis of the experience concrete objects, the visit to the museum is still far from being regarded as a consolidated and rationalized “practice”.We note, therefore, an orientation of the museum education policy, which tends to propose didactical activities that often do not undergo control procedures able to assess the quality of their cognitive effect. The didactical proposals appear undifferentiated for the types of audiences to which they are addressed and school visits to museums reveal themselves episodic and far from the logic of a corporate planned activity. We are obviously drawing some conclusions on the research and it is clear that many significant differences between museums exist, but even among primary, secondary and high school teachers in their way to use the museum as a didactical tool, and that the different groupings reacts differently to these choices. For example, high school teachers use the museum mainly to visit temporary exhibitions rather than permanent collections. Schools very often organize educational activities aimed at the museum as learning instrument, but they turn to museums and more often to local bodies to get the appropriate tools to develop the needed competences.Although there are a quite number of museums providing didactical proposals, they build the own didactical activity mainly through a very heterogeneous staff, generally not equipped with tools of understanding and control of the offer, as it does not have a specific function dedicated to didactics. This underlines the persistent existence of that conflict between the role of the museum as place that collects, preserves and exhibits our cultural heritage and that of a tool, which helps to educate the public through artefacts and objects[19; 20; 21]. This situation is confirmed by the fact that still nowadays, in many museums, there are no equally curators and didactical operators and that the didactical offer, compared to the stimuli coming from school, is a function of the subjective capacity of museum operators to perceive the signals.Even though, nowadays, the cooperation between school and museum is clearly part of school curricula, the dual phenomenon of the attention given to the museum as action and pedagogic support, and the sacred nature assigned by teachers to the museum culture contributes to conceal the dissociation operated between the value systems and the heterogeneous logics of the action. The school-museum relationship is characterized by an underlying ambiguity that goes from the acknowledgement of the didactical forms to the nature of the relationships between teachers and museum operators, but first of all to the statute agreed to museum culture.

3. Learning in the Museum Context

- On the basis of this first analysis, which allowed identifying the functioning and the constitutive characters of the school-museum relationship in Rome, some experimental hypotheses have been conceived in order to develop an experiment in the demo-ethno-anthropological field. We have focused on the impact that the guided tour to a museum produces on the learning process and on the memory of the museum experience, the latter being understood as indicator of the understanding of the message[22]. The experiment was carried out at the National Museum of Arts and Popular Traditions of Rome and the aim was to try to validate a model of guided tour addressed to a school audience (pupils of secondary school). This showed that it is not possible to abstractly determine the quality of the museum experience, but that it is necessary to create the right conditions as to allow that from such experience emerges a precise functionality, i.e. in other words, the need and desire to take advantage from the opportunity that in a specific context, the museum, is offered to strengthen the experience and satisfy certain personal needs.We therefore started from some preliminary questions: does the museum allow learning? How the guided tour to a museum can be improved?[23].The empirical approaches on the educational impact of the museum are still nowadays characterized by the backwardness shown in the attempt to uniquely detect the effects that the expositive elements produce on the behaviour of young visitors[24]. It is obvious that what said cannot be useful to understand the educational impact of the visit, as it is different to talk about the mediations appropriate to foster the learning of the goods contained in the museum and about the organization of suitable didactical exhibitions.Cognitive psychology has shed light on how the behaviour of the individual in relation to the environment is not merely reactive, but rather mediated by the way in which the environment is structured from a cognitive representative level[25; 26; 27; 28]. The construction of the cognitive patterns apt to organize the environment in significative blocks develops through the dialectics between the two moments that Piaget has identified as constitutive patters of each learning process: assimilation and settlement. With reference to the museum, we can say that such learning process can be guaranteed only by the congruence between the interpretation of the material and the visitor’s cognitive patterns.On the basis of these and others considerations, we have chosen to think of an idea of museum education that cannot be left to chance but that needs a specific planning and precise strategies tailored to the pupil/student. Teaching how to analyse different cultural products means in fact to be able to understand any type of communication characterized by different codes. If this is true, it means that one of the ways to make the potentialities embedded in the “good” available is to allow the visitor to receive clear information and enable him/her to process the contents and meanings. The didactical path described here has been conceived exactly with the purpose to overcome an idea of visit to the museum merely based on the oral and relatively transmission of knowledge. In other words, the main objective was to enable children not to stop at the automatic stage of seeing while “passing”, but to reach the organized stage of the observation[29]. Therefore, within the museum context, learning occurs mainly through the observation that requires different skills compared to listening, although listening is another important element of acquisition of knowledge during the guided tour. Attention has been paid on some fundamental matters:● how to improve didactical communication during the guided tour;● how to avoid obstacles to the understanding during the presentation of the objects.To this end it has been necessary to:● choose the itinerary and the objects to show to pupil;● define a reading strategy of the objects;● choose the methods and supports to use.In order to guarantee the improvement of the didactical communication during the guided tour, it has been necessary to control and define the message in a clear and precise way, as we needed to help the young visitor to understand the exhibition topics and their organization.

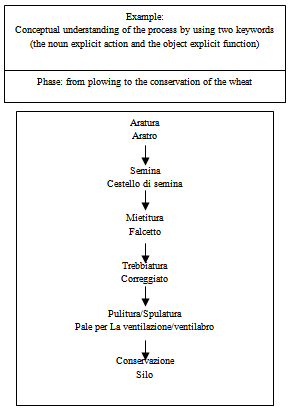

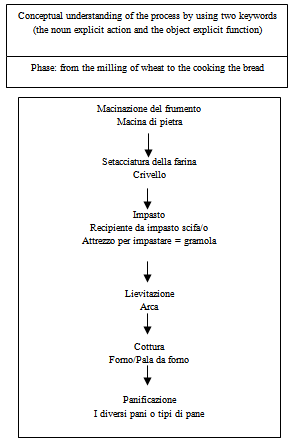

At the base of the experience it has therefore been assumed that, starting from a certain type of guided tour, the adoption of a cognitive and topographical pre-orientation (conceived according to the indication found in scientific literature), able to conceptually direct[30; 31; 32; 33; 34; 35] the pupil, together with the projection of a short film, that had the aim to replace the object in its original context enabling the reading of the material and functional aspects, could increase the understanding both of the single object and of the entire visit process and enhance in this way the memory of the experience even after four months from visit itself. These “tools” have been foreseen within a specific conceptual model of guided tour based on a reading strategy that takes into account the relationship between object / function/context and two criteria: selectivity of the path (number of objects to analyse) and themes of the contents proposed. The title of the didactical proposal can be summarized as follows: Dal grano al pane e dal latte al formaggio: cicli di lavorazione nell’Italia centrale (from corn to bread and from milk to cheese: processing cycles in Central Italy).The experience refers to the rooms dedicated to rural work and dairy production located on the second floor of the National Museum of Arts and Popular Traditions.

At the base of the experience it has therefore been assumed that, starting from a certain type of guided tour, the adoption of a cognitive and topographical pre-orientation (conceived according to the indication found in scientific literature), able to conceptually direct[30; 31; 32; 33; 34; 35] the pupil, together with the projection of a short film, that had the aim to replace the object in its original context enabling the reading of the material and functional aspects, could increase the understanding both of the single object and of the entire visit process and enhance in this way the memory of the experience even after four months from visit itself. These “tools” have been foreseen within a specific conceptual model of guided tour based on a reading strategy that takes into account the relationship between object / function/context and two criteria: selectivity of the path (number of objects to analyse) and themes of the contents proposed. The title of the didactical proposal can be summarized as follows: Dal grano al pane e dal latte al formaggio: cicli di lavorazione nell’Italia centrale (from corn to bread and from milk to cheese: processing cycles in Central Italy).The experience refers to the rooms dedicated to rural work and dairy production located on the second floor of the National Museum of Arts and Popular Traditions. It has been It has been therefore conceived a precise methodology of conducting the “guided tour” centred on a strategy that would focus on the control of the information and of the didactical communication, that is to say on the favourable conditions that contribute to determine a correct reading of museum collections.The visit model has also taken into account the museum environment understood as a perceptive environment and conceptual space allowing the direct and accurate observation of the objects and of their mental representation. The didactical path proposed in the experiment has tried to show to the elementary pupil the relationship between the rural and working history seen through some instruments taken from the material culture. It is clear that bread and cheese have been the excuse to achieve a better understanding of a culture not always close to children’s reality, as the rural culture, which ancient conception was linked to basic food such as bread or cheese.The purposes of the path have been:→ to understand the importance of nutrition and the function of bread and cheese within the rural world of Central Italy.→ to understand the importance of bread and cheese compared to other types of food in the rural culture.→ to understand that the relationship man-food has changed with the industrialization process.This type of experiment has been possible mainly due to three reasons related to the museum structure in question:● its thematic nature;● its focus on visitors;● its didactical service;● its laboratory of visual anthropology.This attempt originated from the need to overcome those difficulties linked to the construction of a didactical path inside the anthropological museum. The complexity of the meanings revealed by the objects on display in this kind of museums, and in certain cases their fragmented nature, poses various problems of decoding and interpretation, but conversely it offers first hand a set of documents (primary sources) that allow a correct historic reconstruction of local cultures. The demo-ethno-anthropological museums are the ones that, in a certain way, can be closer to child’s reality because they create an opportunity to establish a relationship with the territory and environments that are close to him, going through a wide range of routes that go from the pop art object to the utensil used by the man to work. When we talk about demo-ethno-anthropological museums we cannot therefore avoid to think that they collect, differently from what happens for others, not only objects but also tales, songs, spectacles and all those goods that we could define “volatile”, that are nor movables (for ex. vote, chests etc.) nor immovable (buildings and similar) and that differently from an archaeological find, for example, to be enjoyed they must be “executed or redone”, they basically need a recreation (ceremonies, songs etc.)[36]. The oral and gestural characters are fixed on magnetic supports, photographs, videos that do not become mere museum supports but “non-object goods”[37]. The presence of volatile goods, for the cognitive statute of the survey that it is not “collection” but rather “production” of documents[38], characterize these museums and define their documentary character. The use of audio-visual tools fulfils certain functions that in other museums will be unthinkable. The choice to use a film in the experiment becomes therefore a strategic expedient. It is an “object” of the museum collections that lives close to them and that, due to its characteristics, does not talk about the objects but make them “alive”, bringing them back to their original and functional context, beyond how they appear in the expositive one.The aim of the proposed model is linked to three main objectives:● to improve the coding of the stimuli;● to improve the analysis of the given information;● to select the information, maintaining only those that are relevant to not overcharge the memory system (as the aim was to enhance the learning and memory of the experience we made clear to the child which elements were important to remember).The strategy foresaw, through two successive working stages, the support of the message through:● provision of a prior conceptual and topographic orientation, carried out before the guided tour;● the projection of a short film conceived ad hoc for the occasion, projected immediately after the direct look at the objects. The film presented the same objects observed during the guided tour and served as clarification of the object essential elements along with the contextual ones. It brought the object to its original productive context placing it in a precise place and time;● the use of personal cards related to the object to use in the classroom as decoding exercise.The prior cognitive orientation foresaw a preparatory moment carried out partly within the classroom and partly in the museum.In a first clarifying moment, the pupils have been informed of the contents and objectives of the visit. The conceptual itinerary has been previously drawn up and the object reading strategy conveyed to the children.The museum, the selected parts of the collections, the rooms and the objects chosen, as well as the possible difficulties that the child might have encountered during the visit (cognitive orientation) have been presented to the child in a second moment. We now exemplify some difficulties linked to the reading of some common objects.An object on display plays an important function but also many other secondary functions, the kneading trough, for example, is a piece of furniture which main function is to keep wheat or flour, but sometimes it is used also to put away the linen; the upper plane (the lid) of the kneading trough, usually folding, could be used also to knead the bread dough.There are also:● objects that have the same function but are built with a different material: the winnowing-fan, utensil used to sieve small quantities of wheat, made of copper or other metals, but also straw;● different objects that serve the same function: the hoe and the plough are used both to turn the land over (the difference lies in the quantity of land to turn over);● objects that have the same name but can serve different functions (semantic ambiguity): frame with canvas / vegetal elements=filter, frame with canvas=weave and so on.The use of the pre-orientation had therefore the function to provide prior indicators of concepts considered important to improve the attention and direct the learning within the museum[33; 34; 39]. The prior indicators have helped the child to anticipate the organization of the information and to predict possible alternative approaches enabling each young visitor to experience an individual cognitive path. Moreover, they allowed discerning the main elements of the exhibition from small details. This stage served also to settle those prerequisites, i.e., that knowledge essential to approach the visit. We explained to the child the meaning of a museum, what kind of objects a demo-ethno-anthropological museum contains and so on.The pre-orientation had, therefore, the purpose of:→facilitating the adherence to the theme;→providing an orientation from a conceptual point of view;→providing pupils with concept pre-indicators;→proceeding with concision and in a structured/structural way;→meeting the visitor’s inquisitive approach.The film, instead, projected immediately after the vision of the objects inside the rooms where the guided tour took place, suggested again the same objects observed during the path (except those that had been chosen as memory indicators which will be discussed later) clearly defining not only their original and production context but also the functional one. The film acted as a balance between the visualization and the contextualization; i.e. to observe objects for their function. It “told” the function of the object, but it also wanted to create a link between objects belonging to the same category within the entire path.This operation of re-contextualization of the objects on display in the museum space has contributed to show the objects beyond the museum and served to better define the union of the contexts and of their meanings. It is an attempt to make those physical, chronological or symbolic links that join the objects explicit, links that, without such explanation, the visitor would have not easily and spontaneously grasped: probably he/she would have learned the objects independently one from the other.The objects represented in the film were characterized by their relationship with the reality depicted. The film tended to classify the objects of a schematic configuration of meaning, including those places that would otherwise appear undetermined. The undetermined places are those places that are presented to the reader as voids to fill. The film, through the images, gave the object an active role making the “spoken” information more effective and contributing to interpret in a correct way the museum message. In this way we gave back to the single object its intrinsic and functional value; it basically guaranteed a visibility of the expert’s verbal learning acting as bridge between object and word.While pre-orientation had, therefore, the purpose to create a conceptual and spatial map within which the experience could be structured, the film gave back to the single object its main function and/or secondary functions carried out and the value of its identity, as it allowed pupils to observe the objects in their original environment.The film also served to direct the attention towards appropriate contents and activate learning conditions, as it actually linked the museum and functional context with the context of production of the object. The relationship between the functions of each single objects/instruments was activated by the set of meanings that had been enhanced by the reading strategy adopted in the coding of the objects. This has improved not only the understanding of the single object but also the entire visit, considering the proposed path as sequence of objects dealt according to a certain order. This type of presentation of the contents also helped to keep the attention on the contents of the visit starting from the concept of “intrinsic” stimulus.The use of the film during the path has been suggested by three needs to split up the information according to a visual code easy to identify;→to enhance the understanding of the single object;→to increase the understanding of the entire path.The use of pre-orientation and the film besides creating a “conceptual path”[40], conceptually orient the visitor, where to settle the experience, also revealed the need to provide consistency to the didactical communication within the museum enabling a major understanding of the exhibition topics and their organization. The general idea is that between different objects, related to a certain layout of reading, we could create a net of meaningful relationships as to improve the understanding both of the single object and the entire path. We did not provide general information about the path, but we contributed to create homogeneity of the path through the narrative link of the objects creating, in this way, an interrelation of the concepts that can be guaranteed only by a systematic and integrated presentation of the path.A procedure that tried to build coherence within the route and between the set of objects in order to improve the understanding both of the object and of the entire itinerary.We were pretty sure that such structural organization of the guided tour would ease the learning process of the young visitor and help him/her to build a conceptual grid. Moreover, there were reasons to believe that the two factors (pre-orientation and film) would have produced an interaction effect if used in a dependent way.We had, therefore, to start from these conditions to determine the procedure as to achieve the assessment of the hypothesis. This entailed the need to appropriately define the competences considered necessary to successfully face the impact of the visit to the museum, verified before the beginning of the experimental activity[41] and of those abilities that we thought would be acquired with the treatment. Moreover, it has been important to verify the experiment feasibility conditions and clarify the research project.

It has been It has been therefore conceived a precise methodology of conducting the “guided tour” centred on a strategy that would focus on the control of the information and of the didactical communication, that is to say on the favourable conditions that contribute to determine a correct reading of museum collections.The visit model has also taken into account the museum environment understood as a perceptive environment and conceptual space allowing the direct and accurate observation of the objects and of their mental representation. The didactical path proposed in the experiment has tried to show to the elementary pupil the relationship between the rural and working history seen through some instruments taken from the material culture. It is clear that bread and cheese have been the excuse to achieve a better understanding of a culture not always close to children’s reality, as the rural culture, which ancient conception was linked to basic food such as bread or cheese.The purposes of the path have been:→ to understand the importance of nutrition and the function of bread and cheese within the rural world of Central Italy.→ to understand the importance of bread and cheese compared to other types of food in the rural culture.→ to understand that the relationship man-food has changed with the industrialization process.This type of experiment has been possible mainly due to three reasons related to the museum structure in question:● its thematic nature;● its focus on visitors;● its didactical service;● its laboratory of visual anthropology.This attempt originated from the need to overcome those difficulties linked to the construction of a didactical path inside the anthropological museum. The complexity of the meanings revealed by the objects on display in this kind of museums, and in certain cases their fragmented nature, poses various problems of decoding and interpretation, but conversely it offers first hand a set of documents (primary sources) that allow a correct historic reconstruction of local cultures. The demo-ethno-anthropological museums are the ones that, in a certain way, can be closer to child’s reality because they create an opportunity to establish a relationship with the territory and environments that are close to him, going through a wide range of routes that go from the pop art object to the utensil used by the man to work. When we talk about demo-ethno-anthropological museums we cannot therefore avoid to think that they collect, differently from what happens for others, not only objects but also tales, songs, spectacles and all those goods that we could define “volatile”, that are nor movables (for ex. vote, chests etc.) nor immovable (buildings and similar) and that differently from an archaeological find, for example, to be enjoyed they must be “executed or redone”, they basically need a recreation (ceremonies, songs etc.)[36]. The oral and gestural characters are fixed on magnetic supports, photographs, videos that do not become mere museum supports but “non-object goods”[37]. The presence of volatile goods, for the cognitive statute of the survey that it is not “collection” but rather “production” of documents[38], characterize these museums and define their documentary character. The use of audio-visual tools fulfils certain functions that in other museums will be unthinkable. The choice to use a film in the experiment becomes therefore a strategic expedient. It is an “object” of the museum collections that lives close to them and that, due to its characteristics, does not talk about the objects but make them “alive”, bringing them back to their original and functional context, beyond how they appear in the expositive one.The aim of the proposed model is linked to three main objectives:● to improve the coding of the stimuli;● to improve the analysis of the given information;● to select the information, maintaining only those that are relevant to not overcharge the memory system (as the aim was to enhance the learning and memory of the experience we made clear to the child which elements were important to remember).The strategy foresaw, through two successive working stages, the support of the message through:● provision of a prior conceptual and topographic orientation, carried out before the guided tour;● the projection of a short film conceived ad hoc for the occasion, projected immediately after the direct look at the objects. The film presented the same objects observed during the guided tour and served as clarification of the object essential elements along with the contextual ones. It brought the object to its original productive context placing it in a precise place and time;● the use of personal cards related to the object to use in the classroom as decoding exercise.The prior cognitive orientation foresaw a preparatory moment carried out partly within the classroom and partly in the museum.In a first clarifying moment, the pupils have been informed of the contents and objectives of the visit. The conceptual itinerary has been previously drawn up and the object reading strategy conveyed to the children.The museum, the selected parts of the collections, the rooms and the objects chosen, as well as the possible difficulties that the child might have encountered during the visit (cognitive orientation) have been presented to the child in a second moment. We now exemplify some difficulties linked to the reading of some common objects.An object on display plays an important function but also many other secondary functions, the kneading trough, for example, is a piece of furniture which main function is to keep wheat or flour, but sometimes it is used also to put away the linen; the upper plane (the lid) of the kneading trough, usually folding, could be used also to knead the bread dough.There are also:● objects that have the same function but are built with a different material: the winnowing-fan, utensil used to sieve small quantities of wheat, made of copper or other metals, but also straw;● different objects that serve the same function: the hoe and the plough are used both to turn the land over (the difference lies in the quantity of land to turn over);● objects that have the same name but can serve different functions (semantic ambiguity): frame with canvas / vegetal elements=filter, frame with canvas=weave and so on.The use of the pre-orientation had therefore the function to provide prior indicators of concepts considered important to improve the attention and direct the learning within the museum[33; 34; 39]. The prior indicators have helped the child to anticipate the organization of the information and to predict possible alternative approaches enabling each young visitor to experience an individual cognitive path. Moreover, they allowed discerning the main elements of the exhibition from small details. This stage served also to settle those prerequisites, i.e., that knowledge essential to approach the visit. We explained to the child the meaning of a museum, what kind of objects a demo-ethno-anthropological museum contains and so on.The pre-orientation had, therefore, the purpose of:→facilitating the adherence to the theme;→providing an orientation from a conceptual point of view;→providing pupils with concept pre-indicators;→proceeding with concision and in a structured/structural way;→meeting the visitor’s inquisitive approach.The film, instead, projected immediately after the vision of the objects inside the rooms where the guided tour took place, suggested again the same objects observed during the path (except those that had been chosen as memory indicators which will be discussed later) clearly defining not only their original and production context but also the functional one. The film acted as a balance between the visualization and the contextualization; i.e. to observe objects for their function. It “told” the function of the object, but it also wanted to create a link between objects belonging to the same category within the entire path.This operation of re-contextualization of the objects on display in the museum space has contributed to show the objects beyond the museum and served to better define the union of the contexts and of their meanings. It is an attempt to make those physical, chronological or symbolic links that join the objects explicit, links that, without such explanation, the visitor would have not easily and spontaneously grasped: probably he/she would have learned the objects independently one from the other.The objects represented in the film were characterized by their relationship with the reality depicted. The film tended to classify the objects of a schematic configuration of meaning, including those places that would otherwise appear undetermined. The undetermined places are those places that are presented to the reader as voids to fill. The film, through the images, gave the object an active role making the “spoken” information more effective and contributing to interpret in a correct way the museum message. In this way we gave back to the single object its intrinsic and functional value; it basically guaranteed a visibility of the expert’s verbal learning acting as bridge between object and word.While pre-orientation had, therefore, the purpose to create a conceptual and spatial map within which the experience could be structured, the film gave back to the single object its main function and/or secondary functions carried out and the value of its identity, as it allowed pupils to observe the objects in their original environment.The film also served to direct the attention towards appropriate contents and activate learning conditions, as it actually linked the museum and functional context with the context of production of the object. The relationship between the functions of each single objects/instruments was activated by the set of meanings that had been enhanced by the reading strategy adopted in the coding of the objects. This has improved not only the understanding of the single object but also the entire visit, considering the proposed path as sequence of objects dealt according to a certain order. This type of presentation of the contents also helped to keep the attention on the contents of the visit starting from the concept of “intrinsic” stimulus.The use of the film during the path has been suggested by three needs to split up the information according to a visual code easy to identify;→to enhance the understanding of the single object;→to increase the understanding of the entire path.The use of pre-orientation and the film besides creating a “conceptual path”[40], conceptually orient the visitor, where to settle the experience, also revealed the need to provide consistency to the didactical communication within the museum enabling a major understanding of the exhibition topics and their organization. The general idea is that between different objects, related to a certain layout of reading, we could create a net of meaningful relationships as to improve the understanding both of the single object and the entire path. We did not provide general information about the path, but we contributed to create homogeneity of the path through the narrative link of the objects creating, in this way, an interrelation of the concepts that can be guaranteed only by a systematic and integrated presentation of the path.A procedure that tried to build coherence within the route and between the set of objects in order to improve the understanding both of the object and of the entire itinerary.We were pretty sure that such structural organization of the guided tour would ease the learning process of the young visitor and help him/her to build a conceptual grid. Moreover, there were reasons to believe that the two factors (pre-orientation and film) would have produced an interaction effect if used in a dependent way.We had, therefore, to start from these conditions to determine the procedure as to achieve the assessment of the hypothesis. This entailed the need to appropriately define the competences considered necessary to successfully face the impact of the visit to the museum, verified before the beginning of the experimental activity[41] and of those abilities that we thought would be acquired with the treatment. Moreover, it has been important to verify the experiment feasibility conditions and clarify the research project.4. The Research Sample

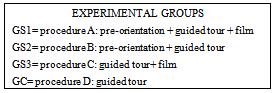

- The sample consisted of 126 fourth and fifth grade pupils between 9 and 11 years of age belonging to three schools located in three different districts of the Municipality of Rome (central area, semi-central area and peripheral area). The selection of the subjects was possible thanks to the indications obtained by the preliminary survey and after a screening on the collective (teachers and pupils) of the Rome schools. We thus identified eight classes, equivalent from the point of view of the museum previous experience and of the visual-motor/spatial skills. Four fourth grade classes and four fifth grade classes, which envisaged, equally, module classes and full time classes for a better representativeness. As the experimental design foresaw four groups: i.e. three experimental groups and one of control, we therefore grouped the original eight classes into four groups corresponding to the different procedures of treatment. Each procedure consisted of two classes with an almost equal number, as to guarantee a sample of eight classes, and a fourth and fifth class for each procedure, and 126 subjects, from which were excluded those that for objective reasons could not be taken into account.The classes have been divided according to the following four procedures:

This because the research design took into account the fact that the guided tour performing procedure suggested within the experiment, entailed the control and isolation of two independent variables (pre-orientation and film) starting from the aforesaid hypotheses. The main hypothesis presupposed that the joint use of these two factors (pre-orientation and film) might have some “impact” on the understanding of the anthropological museum objects and on the retention of the information in the long term, but we had to be able to measure the exact incidence of one (pre-orientation) and of the other (film). But this was not enough; we had to take into account the “guided tour” variable. To this end, all the visit times and the operations necessary for its development have been carefully set since the beginning for each experimental group in order to strictly control the variables: “duration of pupils’ stay within the rooms” and “method of carrying out”. The same visit path and reading strategy of the museum object have been adopted for all classes. Pupils have been trained to the reading of the object within the classroom through the support of an illustrative card. Children’s knowledge and abilities have been measured before and after the experimental work, with a particular attention to perceptive aspects.

This because the research design took into account the fact that the guided tour performing procedure suggested within the experiment, entailed the control and isolation of two independent variables (pre-orientation and film) starting from the aforesaid hypotheses. The main hypothesis presupposed that the joint use of these two factors (pre-orientation and film) might have some “impact” on the understanding of the anthropological museum objects and on the retention of the information in the long term, but we had to be able to measure the exact incidence of one (pre-orientation) and of the other (film). But this was not enough; we had to take into account the “guided tour” variable. To this end, all the visit times and the operations necessary for its development have been carefully set since the beginning for each experimental group in order to strictly control the variables: “duration of pupils’ stay within the rooms” and “method of carrying out”. The same visit path and reading strategy of the museum object have been adopted for all classes. Pupils have been trained to the reading of the object within the classroom through the support of an illustrative card. Children’s knowledge and abilities have been measured before and after the experimental work, with a particular attention to perceptive aspects.5. Results

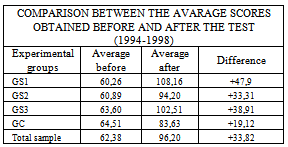

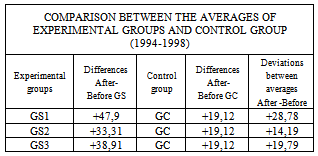

- The results related to the museum learning and the memory of the experience show the close link existing between treatment, learning and strengthening of this learning in the long term, but first of all that when in the absence of a treatment we choose a selective and thematic path, it exists the possibility to increase the understanding.The results of the GC (Control Group), that is the group who did not receive any treatment, show in fact that organizing in a less dispersive way the visit to the museum contributes to turn the latter into a socially qualifying activity, or to say it better, it certainly contributes to increase the learning and the memory of the experience but it is not necessarily needed to guarantee its quality (of this learning and memory). The study reveals, anyway, that the treatment contributes to the retention of the information and guarantees a better understanding of the object and of the entire itinerary; moreover, it underlines the influence that the perceptive heritage acquires in the decoding of the museum message.Compared to the general average of the sample and to the difference between the averages among the groups, we can affirm that the tests conducted on the experimental groups globally obtained better results compared to the ones of the control group and this is proved by the differences in the score obtained by the different groups in the admission and exit tests, i.e. before and after the treatment. Specific parametric statistics tests have been applied to these tests along with the other cognitive and learning tests. Now, we will just highlight the score differences relative to the Before-After of the main test.

The memory dimension of the visit elements (number of objects remembered, correctness of the name of the objects remembered etc.) and the learning dimension (measured though the tests) quantitatively improve in relation to the affiliation to the different experimental groups.

The memory dimension of the visit elements (number of objects remembered, correctness of the name of the objects remembered etc.) and the learning dimension (measured though the tests) quantitatively improve in relation to the affiliation to the different experimental groups. It reaches the maximum level in the GS1 (pre-orientation and film) and in the GS3 (film), while it slightly decreases in the GS2 (pre-orientation) and in the GC (the one which had only the guided tour). This obviously proves another supporting element to the efficacy of the treatment in the interaction of the two factors (i.e. Pre-orientation and Film), but highlights the major efficacy of the “Film” stimulus compared to the “Pre-orientation” one.Pre-orientation is certainly an element that contributes to the increase of understanding, but it is not sufficient to guarantee the preservation of memory, while it becomes meaningful only when it encounters the “strengthening” action of the Film. The visual stimulus of the Film acquires a dominant aspect also and first of all in the dimension and quality of the memory.With regard to the dimension of the memory it is important to underline two measuring conditions. The memory measured immediately after the visit showed that it exists a relationship between the extent of the memory (for example between the number of objects remembered) and the treatment, relationship that remains constant even in the second measurement after four months, period in which it decreases the correctness of the memory (for example the objects remembered with their appropriate name). One of the developed hypotheses is the one related to the fact that the treatment, as foreseen (cognitive pre-orientation and film) within a precise reading strategy of the museum object, would have aimed at the re-creation of the context of use of the objects on display, contributing to increase the understanding not only of the single object but also of the entire visit path. The high conceptualization developed during the itinerary is due to the fact that pupils belonging to the experimental groups clearly remembered also those objects (6 in total) that had been chosen at the beginning of the path as indicators of memory and understanding. Such objects have not been discussed nor during the visit itinerary nor during the presentation of the treatment (film and pre-orientation) as the others; they have not been included in the path in a supplementary or accessory way, but rather as “logic connections” within the itinerary. Nevertheless these objects have acquired a significant role as they appear in the memory “immediately after the visit” in the GS1 (group exposed both to pre-orientation and film) in about 80% of the cases and in 43% of the cases pupils remember more than one of them, in the GS3 (only film) they are present in 78% of the cases, and of these, in 40% of the cases more than one is mentioned; the percentage of memory of these objects strongly decreases in those belonging to the GS2 (20%, and only 2% remember more than one object), while in the GC only 2% remember these objects. This is an important result if compared to the memory that the pupil has of these objects/indicators after four months. The memory is significantly preserved in the GS1 (43%) and in the GS3 (45%), while it is almost inexistent in the GS2 (3%) and in the GC (none). We can therefore conclude that the two factors (Pre-orientation and Film) interact contributing to “capitalize the information”, and therefore made more effective the museum learning and the settlement of the experience in the memory. This didactical itinerary constitutes one of the possible ways that school has to approach the museum, as it certainly offers a model easy to apply that can be usefully combined with the possible other operations carried out with the purpose to enhance the understanding of the museum good. This brings us to the acknowledgment of an education power that the school and museum systems develop when passing from collaborative to negotiating forms, or to say it better towards an articulation of the research fields that have the objective to study instruments able to ease an education of the subjects “in partnership”.

It reaches the maximum level in the GS1 (pre-orientation and film) and in the GS3 (film), while it slightly decreases in the GS2 (pre-orientation) and in the GC (the one which had only the guided tour). This obviously proves another supporting element to the efficacy of the treatment in the interaction of the two factors (i.e. Pre-orientation and Film), but highlights the major efficacy of the “Film” stimulus compared to the “Pre-orientation” one.Pre-orientation is certainly an element that contributes to the increase of understanding, but it is not sufficient to guarantee the preservation of memory, while it becomes meaningful only when it encounters the “strengthening” action of the Film. The visual stimulus of the Film acquires a dominant aspect also and first of all in the dimension and quality of the memory.With regard to the dimension of the memory it is important to underline two measuring conditions. The memory measured immediately after the visit showed that it exists a relationship between the extent of the memory (for example between the number of objects remembered) and the treatment, relationship that remains constant even in the second measurement after four months, period in which it decreases the correctness of the memory (for example the objects remembered with their appropriate name). One of the developed hypotheses is the one related to the fact that the treatment, as foreseen (cognitive pre-orientation and film) within a precise reading strategy of the museum object, would have aimed at the re-creation of the context of use of the objects on display, contributing to increase the understanding not only of the single object but also of the entire visit path. The high conceptualization developed during the itinerary is due to the fact that pupils belonging to the experimental groups clearly remembered also those objects (6 in total) that had been chosen at the beginning of the path as indicators of memory and understanding. Such objects have not been discussed nor during the visit itinerary nor during the presentation of the treatment (film and pre-orientation) as the others; they have not been included in the path in a supplementary or accessory way, but rather as “logic connections” within the itinerary. Nevertheless these objects have acquired a significant role as they appear in the memory “immediately after the visit” in the GS1 (group exposed both to pre-orientation and film) in about 80% of the cases and in 43% of the cases pupils remember more than one of them, in the GS3 (only film) they are present in 78% of the cases, and of these, in 40% of the cases more than one is mentioned; the percentage of memory of these objects strongly decreases in those belonging to the GS2 (20%, and only 2% remember more than one object), while in the GC only 2% remember these objects. This is an important result if compared to the memory that the pupil has of these objects/indicators after four months. The memory is significantly preserved in the GS1 (43%) and in the GS3 (45%), while it is almost inexistent in the GS2 (3%) and in the GC (none). We can therefore conclude that the two factors (Pre-orientation and Film) interact contributing to “capitalize the information”, and therefore made more effective the museum learning and the settlement of the experience in the memory. This didactical itinerary constitutes one of the possible ways that school has to approach the museum, as it certainly offers a model easy to apply that can be usefully combined with the possible other operations carried out with the purpose to enhance the understanding of the museum good. This brings us to the acknowledgment of an education power that the school and museum systems develop when passing from collaborative to negotiating forms, or to say it better towards an articulation of the research fields that have the objective to study instruments able to ease an education of the subjects “in partnership”.6. Replication of the Study to Confirm the Results

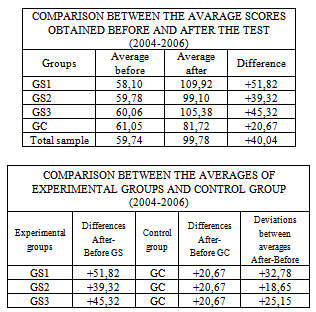

- This research refers to an experiment carried out in the framework of a PhD in Experimental Pedagogy at the University “La Sapienza” of Rome from 1994 to 1998. After six years (2004-2006) we proceeded to repeat the study, which has actually confirmed the main hypotheses of the previous research both on an explorative and experimental level and many of the considerations made. As demonstrated by the results that are summarized in the tables that follow.

The study replicated on the same subjects after six years from the first test has included an in-depth qualitative analysis of the “remembrance” dimension both on the group of subjects selected in the first four years and the group of subjects participating in the second experiment. It confirmed both Stevenson’s results about the character and retention of remembrances by the subjects interviewed after some time from their visit[42] and the fact subjects could remember the emotional state produced during the visit[43] and the emotional response as well[44].Both studies demonstrate that the participating children undergoing the treatment modify their perception of museum visit concept and that they maintain it over time. Interviewed subjects have been asked to assign a contact telephone number. When later on the subjects of both experiments (1994-1998 and 2004-2006) have been contacted by phone and interviewed on the memories of their visit to the museum of some time before, it is evident the significant impact this experience it meant to them, also in terms of number of visits effected by the subjects tested. The subjects’ replies have been analyzed using the content analysis with ADP method[45]. Replies show how the interviewed subjects had detailed memories of their visit even after some time. In particular, the peripheral elements stand out, as well as some visual elements. Moreover, the interviewed subjects seemed to have clear memories of any social contact happened during the visit. This research experience shows the complexity of the variables involved within the educational research we can consider still in fieri[46]. The museum heritage fruition here is intended as a cultural right allowing the access of individuals to symbolic systems brought by culture[47]. It enables transmitting, building, consolidating and strengthening the competences and knowledge supply necessary to each and every individual to exercise his/her active citizenry. It helps in supporting a quality education combining to bring about real opportunities for all the students. This enables the return also to those children deprived of cultural “words” and “alphabets” they need to become the literary men and women of the 21st century[1; 2].

The study replicated on the same subjects after six years from the first test has included an in-depth qualitative analysis of the “remembrance” dimension both on the group of subjects selected in the first four years and the group of subjects participating in the second experiment. It confirmed both Stevenson’s results about the character and retention of remembrances by the subjects interviewed after some time from their visit[42] and the fact subjects could remember the emotional state produced during the visit[43] and the emotional response as well[44].Both studies demonstrate that the participating children undergoing the treatment modify their perception of museum visit concept and that they maintain it over time. Interviewed subjects have been asked to assign a contact telephone number. When later on the subjects of both experiments (1994-1998 and 2004-2006) have been contacted by phone and interviewed on the memories of their visit to the museum of some time before, it is evident the significant impact this experience it meant to them, also in terms of number of visits effected by the subjects tested. The subjects’ replies have been analyzed using the content analysis with ADP method[45]. Replies show how the interviewed subjects had detailed memories of their visit even after some time. In particular, the peripheral elements stand out, as well as some visual elements. Moreover, the interviewed subjects seemed to have clear memories of any social contact happened during the visit. This research experience shows the complexity of the variables involved within the educational research we can consider still in fieri[46]. The museum heritage fruition here is intended as a cultural right allowing the access of individuals to symbolic systems brought by culture[47]. It enables transmitting, building, consolidating and strengthening the competences and knowledge supply necessary to each and every individual to exercise his/her active citizenry. It helps in supporting a quality education combining to bring about real opportunities for all the students. This enables the return also to those children deprived of cultural “words” and “alphabets” they need to become the literary men and women of the 21st century[1; 2]. 7. Future Developments

- Everything has been performed within a wider research programme which main objective was to develop, experiment, assess and validate a model of guided tour addressed to a school audience, that envisaged the experiment within a wider and more articulated debate on the relationship between school and museum. From these studies, in the same direction, we have then carried out further surveys, as the DIDarcheoMUS project (www.incontriamocialmuseo.it), result of the partnership between the University, the Educational Services of the Superintendence for the Archaeological Goods of the region Abruzzo (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Villa Frigerj), the schools of the municipality of Chieti and the Local Bodies with the intent to analyse the collaborative practices in local partnership and with the aim to validate a didactical methodology to be used in archaeological museum contexts in order to improve the educational co-design forms and the collaboration actions between institutions. Everything with the purpose to study and enhance the cooperation between institutions and the networks already present in the territory of the Municipality of Chieti to promote joint actions between school-museum-local bodies aimed at enhancing the strengthening of children, teenagers and adults’ alphabetical skills through the regular and aware fruition of cultural heritage.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML