-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

July, 2012;

doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20120001.02

Family and Disability: An Example of Behavioural Parent Training

Francesca Cuzzocrea , Rosalba Larcan, Anna Maria Murda

Department of Human and Social Sciences, University of Messina, Messina, 98100, Italy

Correspondence to: Francesca Cuzzocrea , Department of Human and Social Sciences, University of Messina, Messina, 98100, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The aim of this paper is to focus on adaptation processes that families of disabled children must realize for a correct beginning of the entire system. In particular, difficulties that parents must face in order to manage maladaptive and non compliant behaviours were analysed. A Behavioural Parent Training was proposed to parents of non compliance children with intellectual disabilities and to parents of non compliance children but with a typical development. Of course, we won’t to compare these different family contexts but underline that, in both situations, it is possible to give adequate support to parents and help them on management children behaviours.

Keywords: Non Compliant, Parent Training, Education, Disabilities

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Any event which breaks existing balances and requires adaptation is potentially a source of stress. Our whole existence is punctuated by stressful events, which force us to turn our resources to deal with them and overcome them, and the way in which we face them, the resources that we are able to activate have a strong influence on the trajectory of our development. The vulnerability to psychological stress is influenced by a number of factors, which relate to the temperament, coping skills, the availability of personal and social resources. In fact, an event is considered a source of distress to the extent that it is perceived as excessive or intolerable or somehow exceeding its capacity to deal with it and overcome it[1]. More an event is sudden, unpredictable, and its effects are more persistent, more resources are scarce, or the perception of self-efficacy that you have to deal with it, the greater the risks involved for their health and for their own welfare both physical and psychological.The life cycle of the family is characterized by a number of more or less critical events that can be caused by different factors, such as entry or exit of a component family, psychosocial issues related to the development of children or simply special events related to the life of the couple[2]. No event in itself, however, is "critical" for the development of the family but it becomes so depending on how it is perceived and the meaning attached to it, which is largely related to the personal experiences of everyone and Believes and social values that are transmitted from generation to generation in the history of each family[3]. The birth of a child is a critical event. This event, although notoriously considered a "happy event" brings the couple to face a number of problems, some of which require a restructuring of the relationship, the usual family routines. Typically, after an initial phase of disorganization, the couple finds a balance and is able to integrate the new baby into the system, which becomes triadic dyadic. But when you add more critical elements, the process of rehabilitation and re-equilibration could be longer and more difficult and requires more resources, both physically and psychologically.

1.1. Processes of Adaptation to Disability: Risk and Protective Factors

- The birth of a child with health problems or physical or intellectual disabilities is one of the most critical events that a family can face. During the period of waiting, all parents expect that their child will be beautiful, healthy, strong and full of life, and they dream for him a bright and successful future. Their legitimate aspirations are, however, strongly thrown into crisis when they become aware of their child's disability. Among other things, to the complexity of emotional reactions to the event, usually they add implications of contingent nature of health and social care.A huge amount of resources are required at the same time. Emotional resources: ability to handle frustration, anxiety, fear, helplessness, which, especially at first, seem to overwhelm parents; cognitive resources: the need to process the event and try to rationalize it, social resources: the need to activate all media in social and family that you may have to better manage the situation, not to mention the economic resources necessary to provide the child with everything he needs, to guarantee him the best possible conditions for development.The announcement of disability is the time from which a new family reality comes to life, many questions crowd the mind of the parents, especially about their future and the future of their child, you have the feeling that nothing can be more like before.Many studies and researches have tried to analyze the psychological processes that lead from the initial shock adaptation. It was found that, even with the differences that may characterize individual realities, the process of "adaptation" develops in five stages: Impact; Denial / rejection / self-deception; pain / anger; Focus outwards; Closing (functional / dysfunctional).The moment of impact is obviously the most critical. Not all face this stage in the same way and there are many reasons that may explain the differences. Temperament, its experienced staff, level of experience and emotional involvement, the socio-cultural background ... but also the way in which the diagnosis is made, the sensitivity and competence of the operators, the availability of adequate support family and social information that you have[4].The next steps are characterized by more or less conscious defense mechanisms, which alternate with periods of unmanageable emotional explosion related with the rejection of evidence and the need to escape suffering. This process of "self-deception" has often the function of creating a break, needed to rebuild their inner balance, put to the test event. The sensation of pain is most acute in the early stages of the process, and it never abandons really the parents who have to deal with a real "mourning" to process: the loss of their perfect and ideal dreamed son during the period of gestation may represent as well as a personal defeat, even a social defeat that resurfaces every time when the gap between the development of their child and the other children becomes more evident. In parents, in a more or less conscious way, there could be mixed feelings: an excessive attachment to the disabled child, which leads them to an absolute and indiscriminate dedication and, even at the expense of the well-being of themself and the other members of the family, the refusal more complete, the desire that he was never born…Frustration, embarrassment and guilt that inevitably follow, cause sometimes the parents forms of insulation from external reality: they gradually stop social relationships and, in some cases, fall into depression. In many cases, however, it has a focus outwards. They are looking for specialists and new and different diagnosis or miraculous interventions. Then, gradually emerges the rationality and take over the gradual adjustment to the new reality. The needs of the child take over, you begin to create new routines and just these routines promote the adaptation process. The last and final phase of the process is the "closure". In fact, the circle is closed, but the timing and the manner of such termination, in terms of function / dysfunction, may be very different for different families, depending on many factors.The first thing that can actually make a difference is the type and severity of disability. Numerous studies on the subject have shown significant differences in the time and manner in which it carries out the process of adaptation to the disability of a child[5]. Specifically in relation to the type and severity of disability that is diagnosed, the parents expect a certain kind of development and the type of complications related to it.Equally important are certainly the cognitive, emotional, social, relational and experiential reactions of parents, considered both individually and as a couple. Their physical resources, personality characteristics, their way of dealing with problems and stress in general can certainly make a difference[6; 7].Another important and crucial element of variability is given by the level of satisfaction of the couple and family functioning. It has often been observed that the family system, not only in terms of the marital relationship[8], but also extended family, may represent, as appropriate, a major source of vulnerability or an extraordinary resource. Finally, an important place is given by the possibility, for the family and for the child, to enjoy adequate social, psychological and health support. Both in the case in which the disabled child is the first child, both when there are other children, the organization and management of the ménage family and the use of a suitable parenting can be particularly difficult[9; 10]. Parents, if not properly supported, especially in the critical phase of the adaptation process, are likely to make educational mistakes that can have a significant impact on both the emotional and cognitive development of the child with a disability and, when present, also of the other children. The involvement of other children in the household is inevitable. In most cases, to them, especially if he/she is older than his brother disabled, are assigned roles and responsibilities of proportion to their age. Attention, mainly centered on brother with disability, place them in a position of emotional marginality, often evokes ambivalent feelings towards his brother, with repercussions on the relationship and development in general. In some cases have been reported depressive episodes, psycho-social developmental delays and academic underachievement[11]. For a long time the literature has tried to identify the critical factors of families of children with disabilities, and the main risk factors have been analyzed and discussed[12]. The variability of the results has increasingly highlighted the opportunities for more detailed investigations into resilience factors, both at the level of individual response to stress, both at the level of the family system[13]. If, at the individual level, the main protective factors seem to be coping skills and problem solving, and of course, a set of personal characteristics, cognitive, emotional and socio-relational to a level of protection factors that found more scientific confirmation, they can be summarized in some points.(1) Family consistency and cohesiveness, the ability, that is, to negotiate and harmonize meanings, emotions and behaviors, and the ability to create optimal conditions for a functional organization and above all sharing routines. The latter aspect was of particular importance, both for the purposes of family stability and for faster development of the processes of adaptation, (2) cognitive coping, i.e. the shared representation of disability, causes and control options and (3) adaptive styles and consistent child management. Frequently, child's difficulties make parents anxious and over-protective. This attitude precludes many learning opportunities to the child and makes him insecure, emphasizing, instead of improving, his condition of discomfort and disadvantage.The inability to properly address and correct some behavioral excesses, often found in children with disabilities, significantly increases the stress levels of parents and reduces their sense of self-efficacy parenting. If you add this element to their already fragile psychological condition, it is not difficult to understand why the stress levels of parents of children with disabilities are usually very high, especially when compared with those of parents of typically developing children[14; 15]. The difficulty to remain calm when my child gets insistently oppositional behavior or refuses to cooperate with the medical and psychological treatments, results in an escalation of emotions that can come up aggression, the emotional difficulty to punish or correct children maladaptive behavior, can be translated into a growing increase in behavioral problems that makes difficult not only family interactions, but also the rehabilitation and the lack of coherence, intra-or inter-parental, in the management of behavioral rules, certainly detrimental in the education of children in general, it is considerably more towards children with disabilities who, more than others, need simple and clear rules and consequences stable and consistent in their behavior. Rarely parents program an individualized educational plan for their children, delegating this task to the experts, i.e., teachers and rehabilitation technicians. It is therefore essential that parents, teachers and therapists share principles, rules and educational behaviours. It often happens that the lack of consistency between the various educational agencies creates confusion in the child and significantly prolonged treatment, making it sometimes frustrating.More and more it confirms the need of psychological and social support for families of children with disabilities and health care and rehabilitation.

2. Training to Families of Disabled Children

- On the basis of these considerations, when designing an intervention on the family, there are several factors that must be taken into account. You have to make an accurate preliminary assessment not only of the likely elements of vulnerability, but also the resources of the child and the family.In particular, the main aspects that should be considered include: the behavior of the child, in its cognitive, emotional-affective and relational parents' behavior, both in general and in relation to its cognitive, emotional and relational components, and more specifically in relation to parenting skills, the representative aspects, both in relation to internal working models, both in relation to the meanings attributed by parents to disability and the behavior of the child; aspects of the organization and family functioning (structure of family, couple satisfaction, relationships with their families of origin); aspects of the broader social context (social support, work experience, etc.); relational dynamics (intra-and extra-familial).An intervention can be considered valid, if it act on all levels on family members involved. It must be able to change and adjust believes, emotions and dysfunctional behaviors, should promote personal and parental self-efficacy and should stimulate synergy within the family system and with external systems.The access to the family system can be realized through different modes, in relation to what emerges from the initial assessment, even if, as suggested Sameroff[16], any way they choose to enter the system, effects of change should nevertheless occur on all levels of the system.In some cases it may be enough to intervene directly on the child (repair) to occur significant effects of change in the functioning of the entire system. Other times it may be more useful to change the perception that parents have a disability and the child's behavior (actions redefined). In other cases, however, may prove decisive action on parenting skills (interventions of rehabilitation), and indirectly to change the child's behavior, and the perception of those parents. Improving the quality of parenting, breaking cycles of coercion in which many high-risk families seem hopelessly trapped, can be, in fact, feasible to resize noncompliant children and act indirectly on the influence of other risk factors, such as intra-individual and those contextual.Among the numerous re-education proposed by applied research in recent decades, the parent-training matrix behavior, it seems one of the strongest in the short and long-term[17-22].The training model that is proposed here is not meant to be conclusive, but it may be considered an effective educational intervention, because, without going directly to the specific family dynamics, suggests a functional and flexible interactive mode, not only, that is, transmit, as it may seem, parental management techniques, but also provides learning relational skills that can have a major impact on the functioning of the entire family system.

2.1. An Example of Behavioral Parent Training

- Like any behavioral parent training group, the course is characterized by its brevity (10-12 provides weekly meetings, lasting about 2 hours each), and its structure is experimental (For a more detailed description of the program, see Larcan, Oliva and Sorrenti[9]).Before you begin any of the training sessions, it is essential to provide a number of meetings, both with the individual pairs, and then in a group, for the evaluation of medical records. During these meetings, questionnaires and psychometric tests, providing measures related to the factors on which the training is intended to act are administered. These tools are then replicated at the end of the training to assess their effectiveness and, after some time, to verify the maintenance of learned skills and persistence of change.It is important that the groups are not too numerous (no more than 8-10 pairs) and are sufficiently homogeneous with respect to socio-cultural, age and basic issues.The training is divided into sessions that are developed according to a precise task analysis and includes learning some basic behavioral techniques for management education of children of preschool and school age. Given its structural characteristics, can be easily adapted to different contexts and situations. It can also be expanded or supported, in cases where it is deemed necessary, with additional sessions dedicated to the learning of soft skills and the "redefinition" of representative aspects dysfunctional.The first meeting is devoted to familiarization of the group and the setting of objectives, in particular the goal is to shift the focus of disturbing behavior by parents of the child, which often have a distorted perception, those adaptive and functional. The focus of the meeting is therefore an important systematic observation of children’s behaviours.In the second meeting, the parents, through films and examples proposed by the trainer, learn to observe and analyse their own behaviour and that of their child on the basis of functional relationships with the events that precede and follow them, and in relation to the contexts in which they manifest themselves (functional analysis of behavior). In addition to practice with each other, under the supervision of trainers, parents are invited to put into practice the skills learned in their family context, using diagrams and charts specially crafted to be commented on and discussed at the beginning of each subsequent meeting. This procedure has the advantage of allowing the trainer to gain a more direct contact with the environments and situations where problems occur and to provide parents with appropriate feedback regarding the quality of their strategies to be used against the child. Learning and verifying directly as changing contingencies can change behavior and the quality of interactions is definitely functional to eradicate some of the assumptions on the behavior of the child, believed, in general, closely related to disability or at least an expression of unchangeable traits of his temperament.The third and fourth meetings are dedicated to learning techniques for increasing adaptive behaviors. Parents, learn to pay more attention to the behaviors of children, generally taken for granted and not sufficiently "rewarded". Young children, especially those with disabilities need to understand clearly what adults expect of them, what they like. One of the key things that parents need to acquire is the importance of intra-and inter-parental consistency. In these meetings, in particular, they learn that reinforcing positively good behaviors of children increase them in frequency. As a result, children will feel more appreciated and also improve the mood of parents: to experience early success in interactions with the child will change some of their misconceptions and gradually increase their sense of self-efficacy parenting.The meetings that follow (from fifth to ninth) are dedicated to the acquisition of some basic skills. Their aim is to decrease the frequency or eliminate the inappropriate and disturbing behavior of the child. Parents, then, must learn to use correctly and effectively the techniques punitive, often implemented in an inconsistent manner and in conditions of exasperation, then without calibrate and adjust sufficiently their emotions and without first having tried other behavioral strategies less unsightly and often more effective (such as the Override or the differential reinforcement). Once parents have learned basic behavioral techniques for children education management, they can focus on the central theme of the training: how to get compliance. For any parent it is easy to remain calm when the child refuses insistently to comply with his requests or stops acting up. And the choice to waive or insist worse to avoid him requests is equally inadequate as going to escalate until having to resort to punitive methods ineffective and harmful. Unfortunately, both choices are the result of a learning process, which is likely to perpetuate the inadequate interactive mode. The avoidance behaviors or condescension of the parent reinforce the oppositional behavior of the child, as well as the ability to avoid the persistent waste of his son and the tension that comes in the interaction reinforce the inadequate educational choices of parents. Sometimes it will necessary few simple about how and when it’s better to ask questions or how to react to the first refusal, to escape from the trap interactive defined by Patterson[23] cycle of coercion. Parents, then, in the light of what was learned previously, learn to address adequately even in the most difficult situations and handle them in an efficient and satisfactory way.Finally, parents learn to use more elaborate and functional techniques learned, with the goal of making the children more and more autonomous and able to self-manage their behavior. Eleventh session of the training, then learn to design and implement a token economy program, which basically consists in the gradual postponement of enhancers. When the age and level of cognitive development of children permits, a token economy program can be useful not only to change maladaptive behaviors of a social nature (lack of autonomy in the management and control of their bodies, physical and verbal aggression, discord among brothers, etc..), but to promote, in an easy and fun way, to learn a variety of other soft skills, such as, earn what you want, know how to wait, make decisions, solve problems, etc.., essential to for autonomy and self-regulation.The last part of training has a dual purpose: to make parents more independent and effective in the management of behavioral education of their children and encourage a more valid and competent collaboration between family and professional rehabilitation. Parents learn in an easy and accessible way how they can teach new skills to their children. Obviously it doesn’t mean that parents are as able as a rehabilitation technician; you just want to make them more actively involved and aware of the treatment program. The ability to act synergistically with family members would make it possible for therapists to work more quickly and effectively, and the results will be easier to maintain over time[24].

3. A Brief Report of two Experience of Parent Training Program - Methodology

3.1. Participants

- The example of testing proposed here compares two parent training courses, made with similar procedures and the same trainer of two different groups of families. In order to obtain the necessary information for sampling, a Socio-cultural format was completed only in the assessment phase. It provided indications on the age, parents’ work, family components, children characteristics (age, gender and kind of disabilities if present). In addition, all parents had to indicate 3 positive and 3 negative children’s behaviours.The first group was composed by families with a disabled child who presents non compliance behaviours. 10 families were selected, all belonging to a low socio-cultural level; aged between 35 and 47 (m=39.25; sd=4.06). Their mentally retarded children were aged between 7 and 11 (m=8.36; sd=1.5). They had been followed by the same therapist for 1 year.The second group was composed by families with nondisabled child who presents non compliance behaviours. 10 families were selected, all belonging to a low socio-cultural level; aged between 35 and 47 (m=40.23; sd=3.96). Their children were aged between 7 and 11 (m=8.36; sd=1.7).Study participation was voluntary and all the parents, after the presentation of the project, signed informed consent forms.

3.2. Procedure

- Like any behavioral parent training, the proposed program is divided into several phases. In the initial phase (before the course), there are a number of meetings devoted to the evaluation of some aspects of family functioning and personal characteristics of the individual components. This phase of the assessment is repeated at the end of the course, in order to verify the effects. Generally, meetings are scheduled follow-up to verify, in different time intervals, the maintenance of the effects of training.Among the various formats provided for the construction of behavioral parent training (individual / group), there is the privileged group format because it was considered easier and more effective. The opportunity to meet families, who are experiencing a similar discomfort, allows parents to come out of isolation in which they occasionally are and confront shared challenges. Learning is more rapid and enduring effect also for the modeling; motivation is therefore higher and the effects are maintained longer.To verify the effectiveness of the trainings, the research foresees 5 phases: (1) Pre-training, (2) Training, (3) Post - training, (4) I Follow-up, after three months, (5) II Follow-up, after six months.

3.3. Measures

- Participants were asked to fill out the Italian version of questionnaires, individually presented. The order was balanced within groups. To verify the effectiveness of the trainings, the following questionnaires were proposed before starting the training, at the end of the training, after three months from the end and after six months:- Questionnaire for parent’s evaluation of their child’s problems was proposed in order to obtain information about parent’s perceptions of child’s behaviour at home, personal autonomy, and interactions, 47 items were selected. The parents had to mark the frequency of the issue of the behaviour choosing among never, rarely, fairly often, often and always.- Questionnaire for the Evaluation of Parents’ Educational Skills - QVCE[25] contains 10 items each proposing a behavior supposedly issued by the child. In particular, 5 items refer to behaviors and the other 5 to inappropriate behavior. For each item there are 4 alternative answers, which, based on the model of education, establish educational strategies at different levels of adequacy. Each alternative response is given a different score, from 4 (the best choice) to 1 (the choice less adequate). For each proposed behavior the parent is asked to indicate how often (low, medium or high frequency) it is issued by his son, because the educational solution commonly used may be assessed differently depending on the frequency of issue indicated. The scores that can be assigned ranging from a minimum total value of 10, to a maximum value of 40, that are indicative of a different level of expertise relating to the educational management of the discipline. The reliability of the total number score in this study was good both for families with disabled children (α=.89) and with nondisabled children (α=.90).- CDQ – IPAT Depression Scale[26] is a self-administered questionnaire of 40 statements, through the examination of which it is possible to define the degree of depressive illness presented by parents. The reliability of the total number score in this study was good both for families with disabled children (α=.92) and with nondisabled children (α=.87).- ASQ – IPAT Anxiety Scale[27] is a self-administered questionnaire of 40 statements, that measures the degree of anxiety present or not in the subject (disabled children parents: α=.89; non disable children parents: α=.90).

3.4. Results and Comments

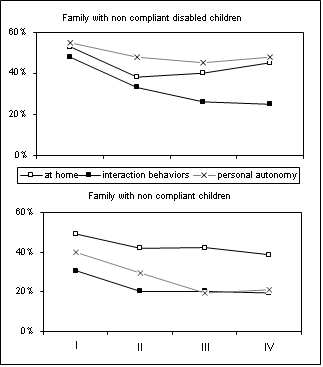

- The aim of this report was not to compare the two groups, but only to underline the training efficacy in two different contexts. The Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) was used to verify the hypothesis. A non-parametric statistic was used to analyse scores obtained by parents. In order to verify statistical differences within phases, Friedman tests[28] were calculated separately on dependent variables. The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test[29] was calculated to verify statistical differences in simple comparisons within phases.Figure 1 represents parent evaluation of children’s behavioural problems during four phases of measurements.

| Figure 1. Parent’s evaluation of children behavioural problems |

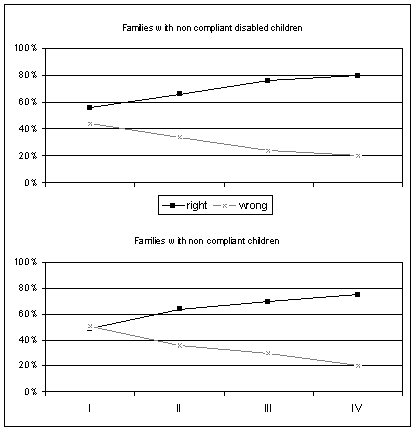

| Figure 2. Parents educational chooses during the phases of evaluations |

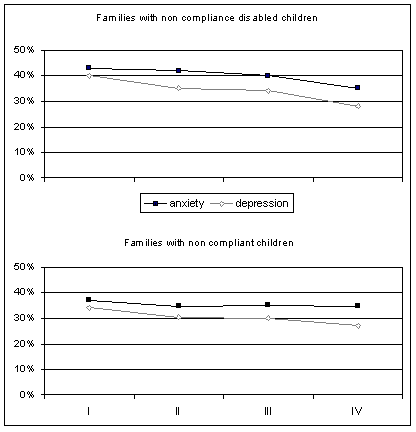

| Figure 3. Levels of anxiety and depression in parents during the forth phase of evaluation |

4. Conclusions

- This program, already tested several times with different types of family groups[30; 31], was found to be valid and enforceable. Parents have the opportunity to deal systematically with each other and with an expert, and they can learn, at the same time, the most correct way to address educational issues in their everyday life. Many of their preconceptions about the child's disability and its possibilities of learning and development, collapse in front of the possibility to experience the effectiveness of the methods used in treatment. Above all, they are made aware of the possibility of being able themselves to have control of the situation, with great benefit to their sense of self-efficacy, personal and parental and family well-being.We know that the rehabilitative treatment of children with learning and behavioural disabilities require time and a constant and intense effort[32] with obviously high costs for families and for public health. The validity and effectiveness of these interventions of parent training proved for decades by those who work in this area, should make us reflect on whether to support systematic use of rehabilitative interventions on children, this type of training support for parents. The benefits are in fact many, both at the micro-system (reduction of anxiety and depression, which are often present in families of children with disabilities, improving the overall family functioning, with repercussions on the development of other psycho-social children), both meso-systemic (is enhanced collaboration between different educational agencies, who can share programs and methods in working with children and each other), and also at the macro-systemic (reduction of social costs, both in economic terms, both in terms of general health and prevention of further trouble). Certainly, much more can be done to enhance its effectiveness. One of the limitations identified in the scientific literature, for example, is the fact that these courses, once you reach the goal, end, except for some calls (follow up) within a few months. If this design pattern can be valuable and interesting in terms of experimentation, it might not be as then the systematic rehabilitation centers. In fact, there are too many variables that can, with the passage of time, to dim the effects and thereby reduce their effectiveness, especially in terms of effective collaboration and coordination with service operators. It would therefore be appropriate for family members (including, for example, the brothers), and possibly also for teachers, parallel paths to the rehabilitation of children with regular meetings booster in order to share and discuss all the problems encountered and to coordinate possible solutions[33; 34].Even more profitable, in our opinion, these activities could be carried out in a timely manner. As mentioned above, the most critical, stressful and problematic period, for families of children with disabilities is what sees them engaged in the process of adaptation, the period, that is, where all their resources, such as personal or family history, are required; the period in which they need a great support. For this reason, at present, we are planning interventions to accompany the couple during the transition to parenthood, especially in cases where it is considered least likely diagnosis of a disability. And, even in this case, a coordination of all the actors involved (both in health care, both in education and rehabilitation) is considered essential for the functionality of the intervention. Furthers research should be take into account the conditions of applicability in different contexts and the variability of its related conditions (as stated in the study) who sees the families of children with disabilities involved in the adaptation process, in which the support it must be expressed in different forms. This dimension is essential for the functionality of the interventions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML