-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2025; 15(1): 11-19

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20251501.02

Received: Apr. 22, 2025; Accepted: May 12, 2025; Published: May 17, 2025

Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa Face to International Terms of Trade of Fluctuation

Irifaar SOME

Joseph KI-ZERBO University, Burkina Faso

Correspondence to: Irifaar SOME, Joseph KI-ZERBO University, Burkina Faso.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The terms of trade to area of internationalization and liberalization of trade cause a lot of interest for Sub-Saharan African countries. This document analyzes the relation between the variability of the terms of trade and the economic growth of Sub-Saharan African countries, with econometric model for 27 countries on panel data. After model specification, the estimation results by the Pooled Mean Group (MCG) estimation show that the terms of trade positively affect growth while the terms of trade variability negatively affects the growth of Sub-Saharan African countries. This result point up the effects of the problem of the terms of trade deterioration evoked since 1950.

Keywords: Terms of trade, Variability, Growth, Sub-Saharan African, PMG

Cite this paper: Irifaar SOME, Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa Face to International Terms of Trade of Fluctuation, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 11-19. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20251501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In this context of globalization, where the opening up of economies is reflected in a sharp increase in international trade, the terms of trade (ToT) are the subject of intense debate. On the one hand, the dominant literature accepts that international trade is mutually beneficial to all partner economies. On the other, however, a growing body of analysis suggests that the gains from trade depend on the nature of the specialization that determines the nature of the goods traded. This hypothesis forms the basis of the debate on deteriorating terms of trade, which dates back to the studies by [1]. The downward trend in the relative price of exported primary products would aggravate the balance-of-payments constraint of these countries, all of which would contribute to reducing their economic growth. Conversely, by alleviating balance-of-payments constraints and increasing production, an improvement in a country's ToT (terms of trade) should lead to growth in its GDP (Gross Domestic Product), as the rise in the relative price of exports makes it possible to purchase production inputs in greater quantities, and to invest in productivity-enhancing measures, such as more efficient production technologies [2].However, while the literature seems unanimous on the relationship between ToT and economic growth, the downward trend in ToT for primary products is no longer proven in this context of declining trends or stagnating prices for manufacturing products. In fact, according to [3], the introduction of China to the world market would have been at the origin of a downward trend in the relative price of manufactures. In this respect, the focus of interest on ToT has shifted to the effects of their variability on economic growth in developing countries. In this respect, it seems that the greater the degree of openness of an economy, the greater the impact of a variation in its terms of trade on growth. In addition, it is estimated a priori that variations in an economy's terms of trade are all the stronger when it has a low number of specializations centered on primary, agricultural or mining products. Unlike manufactured goods, unprocessed agricultural and mining products, as well as petroleum products, are subject to strong price variations on the world market, depending on international economic trends. Economies that are highly specialized in these products are likely to be much more exposed than others: strong variations in terms of trade multiply both the risks of losses and the opportunities for gains generated by world trade.For African countries, the large share of export earnings from mineral and agricultural raw materials is very important. According to the WTO (World Trade Organization), in 2012, agricultural products accounted for 9.1%; fuels and mining products accounted for 69.5% of Africa's global exports, compared with 16.4% for manufactured goods. At the same time, commodity prices are highly variable (cocoa prices have followed a downward trend, falling from $3,730 per tonne in 2009 to $3,174 per tonne in 2014; cotton prices have risen from $1.65 per kilogram in 2010 to $2.00 per kilogram in 2014, according to the International Cocoa Organization). In global terms, for a country like Burkina Faso, the terms of trade index, based on the year 2000, fell from 119.24 in the 1990s to 93.47 in the 2000s, a deterioration of 21.26%.At the same time, income disparities between industrialized countries and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have widened. Indeed, in 2012, for example, gross national income per capita, Purchasing Power Parity in 2005, was $2,010 in Sub-Saharan Africa; $10,300 in Latin America and the Caribbean and $12,243 in Europe and Central Asia, according to the Human Development Report.In view of these facts, we can only wonder about the factors behind the poor performance of SSA countries. In particular, are the income gaps between SSA and industrialized countries explained by changes in the terms of trade? The general aim of this article is to analyze the influence of fluctuating terms of trade on economic growth in sub-Saharan African countries.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Aspects

- Terms of Trade (ToT) had already been formulated in the 1950s by [4], who argued that a deterioration in ToT would lead to a loss of income, a reduction in savings and, consequently, a deterioration in the current account. However, [5] later contradicted the Harberger-Laursen-Metzler proposal, showing that when countries' rate of time preference increases, a deterioration in ToT will lead to an increase in their savings rate and current account.The effects of international trade on growth and the well-being of co-traders have been the subject of several theoretical debates; a synthesis of this literature can be proposed, distinguishing three main lines: the important role of international trade for growth according to orthodox theories, the Marxist approach and its controversies.The importance of international trade for growth can be traced back to the very beginnings of international trade theory, with differences between nations as the main basis for exchange. In his Investigations into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, [6] highlights the role of the division of labor (surplus, market, productivity gains) as a growth factor. This division of labor is reinforced by the country's participation in international trade (absolute advantage theory). Smith's optimism is reflected in the features of unlimited growth (it lasts as long as the division of labor and the market can be extended).In the 19th century, David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage demonstrated that international trade enabled countries to redirect their scarce resources towards more efficient sectors, thereby improving their well-being. These gains were later confirmed by the theories of David Ricardo Ohlin? Heckscher and Samuelson, known as the HOS theorem (Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson theorem). To boost production, Ricardo advocated increasing productivity gains in agriculture through technical progress and opening up to international trade (theory of comparative advantage). He thus demonstrated that specialization and openness to trade are sources of growth.According to the HOS theory, different nations are led to export products incorporating a high quantity of production factors that they possess in abundance, and to import products incorporating a high quantity of production factors that they are poorly endowed with. This will enable them to benefit from international trade in terms of well-being and increased production.Endogenous growth theories [7] have also highlighted the existence of dynamic gains (with an impact on income growth and not just on its level), linked in particular to economies of scale (hypothesis of increasing returns) and to the diffusion of technical progress favored by trade.However, these gains are not guaranteed, and models inspired by these new theories show that openness can push the countries concerned towards specialization in less dynamic sectors, with an overall negative impact on growth [8]. The example of developing countries specializing in the export of raw materials for which demand is not very buoyant shows that these models are well suited to the experience of many countries, bearing in mind that the theory of the downward trend in the terms of trade for primary products in vogue in the post-war period [1] also pointed in the direction of lower growth for countries exporting these products.

2.2. Empirical Literature

- At the empirical level, the various studies on ToT and growth can be grouped according to the results of the studies.Positive impact of terms of trade on growth[10], using a neoclassical growth model by Robert Solow, shows that changes in the terms of trade play a role in structurally determining the growth rate. Similarly, [11] find that the variability of ToT is strongly correlated with growth, particularly in the 1980s, while economic policies (such as education and stabilization policies) and country characteristics contribute less to explaining economic performance. Unlike these authors, who rely on deterministic models, [12] analyzes the effects of ToT using a stochastic model. His results show that the effects of ToT depend on the difference between investment rates and expected domestic savings. Similarly, [13] study based on the stochastic general equilibrium model concludes that 56% of GDP fluctuations in developing countries are due to terms-of-trade shocks.[14] with a study of twelve developing countries, mainly in Latin America, support the hypothesis of “the positive impact of ToT on growth”, as emphasized by [15], Using annual data for the period 1961-87 to estimate SUR (seemingly unrelated regression) models involving commodity prices, [16] corroborate this hypothesis for African countries as a whole. [17] have carried out empirical work using the VAR model to determine the origin of macroeconomic fluctuations in developing countries. Their analysis focuses, on the one hand, on external shocks, which they apprehend through the terms of trade and the world interest rate, and, on the other, on domestic shocks (supply or demand shocks). [17], after positing long-term restrictions, established that these shocks are essentially responsible for macroeconomic fluctuations in developing countries.According to their results, the terms of trade and the world interest rate explain respectively 7% and 6% of output variations in Asia; and for sub-Saharan countries, the contribution of the terms of trade appears higher (15%), while that of the world interest rate remains similar [17]. Furthermore, [18] find that the terms of trade are more important in explaining growth, with a more significant effect in the pooled estimate than in the between estimate. [19] corroborate this hypothesis.Taking up the model developed by [20] who used an endogenous growth model with one sector in a small economy, Enrique G. Mendoza (1995) shows that variations in ToT determine savings rates and growth. Thus, growth slows down in economies where the terms of trade deteriorate, as the fall in the ToT affects gains from trade. The model predicts that variation in ToT, as an indicator of risk, helps explain growth. [21] used the same model as Mendoza to analyze GDP per capita growth in 14 sub-Saharan African countries between 1980 and 1995. They found that investment increased as ToT improved in all the countries studied.The conclusions of studies on the origin of activity fluctuations based on the stochastic general equilibrium model follow the same trend. Firstly, [13] concludes that 56% of GDP fluctuations in developing countries are due to terms-of-trade shocks. [22] show that relative prices explain 44% of fluctuations in productive activity in African countries. The results of [22] show that these shocks contribute 90%. Negative impact of terms of trade and their variability on growthEvoking the “curse of natural resources” hypothesis, [23] show that any improvement in the terms of trade thanks to natural resources has a negative impact on growth, since, in their view, these improvements induce rent-seeking activities. These rent-seeking activities tend to be unproductive and unprofitable, resulting in lower growth. Moreover, for some authors, rents from natural resources due to improved ToT would have a corrosive effect on institutions [19].Furthermore, [2] conclude that for African economies, instability of export prices or ToT does not seem to explain the low growth recorded by several of these countries, but his results indicate that it is the trend in ToT, and not their variability around this trend, that would matter for growth because for him “the deterioration in the terms of trade has a significant negative impact on growth in sub-Saharan Africa, both directly and indirectly, via investment”. This result is later corroborated by [22], who find a negative cumulative impact of ToT on growth in the case of Nigeria, but conclude that this result could simply be a reflection of the volatility of ToT, using data for the period 1981-2002.In a similar vein, [21] come to similar conclusions. Based on a sample of 14 SSA countries, they also conclude that the volatility of the ToT was detrimental to growth from 1980 to 1995, despite the positive effect on growth of the improvement in the ToT. Using panel data [24] find for 61 developing countries between 1975 and 1992 that an increase in the growth rate of the terms of trade has a weak positive effect on the average growth rate of output, while an increase in the volatility of the ToT has a strong negative effect on output growth. Their results hold for both high and low samples. [21] confirms this relationship, arguing that the economic slowdown in peripheral countries was due to the negative ERU shock during the First World War. He argues that the negative ToT shock depresses export revenues and capital inflows, as investment becomes less attractive. Based on a sample of 14 African countries, [21] lend further credence to this hypothesis.According to [25], the volatility of export prices disrupts countries' macro-economic management, discourages domestic and foreign private investment and maintains the vulnerability of African economies. [26] have carried out a study on ToT shocks and development. They confirm Prebisch's hypothesis that relative price shocks between 1870 and the First World War tended to reduce growth performance in certain zones. Furthermore, [22] examine the role of import and export price fluctuations in explaining macroeconomic fluctuations in 22 non-oil-exporting African countries between 1970 and 1990 with a multi-sectoral model of a small open economy, and adapting African data to this model, they find that fluctuations in the prices of tradable goods on the world market strongly explain half of the fluctuations in aggregate income. The negative effects of terms-of-trade instability were also highlighted on a panel of four periods from 1965 to 1997, when growth and openness were estimated simultaneously by [27].Once the influence of structural factors has been controlled for, growth depends significantly on the terms of trade in three ways: their growth has a positive effect; their instability, weighted by the structural component of openness (i.e. structural vulnerability to price volatility), has a negative effect. It emerges that the effects of structural vulnerability are largely mediated by economic policy variables, and translate in particular into instability of public investment and instability of the real exchange rate, both of which reduce growth.

3. Descriptive Analysis

3.1. Variability in Terms of Trade

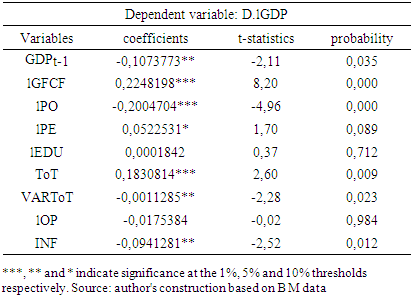

- The most important aspect of the terms of trade is their evolution over time (Chart 1): if we observe a “deterioration in the terms of trade”, this means that the price of exported products has risen less than the price of imported products. In other words, it means that greater quantities of products will have to be exported to import the same quantity as before. The concept of ToT variability refers to the fluctuation of ToT around the average. Graph 1 illustrates the variability of ToT in 27 SSA countries. Thus, the evolution of the terms of trade is an important economic factor for SSA, firstly from the point of view of the benefits a country can derive from international trade, then from the point of view of the balance of trade, and finally from the point of view of the structure of the various countries. When the terms of trade increase, exports can be exchanged for a greater quantity of imports.

| Figure 1. ToT and ToT variability in SSA |

3.2. Correlation between ToT Viability and Growth

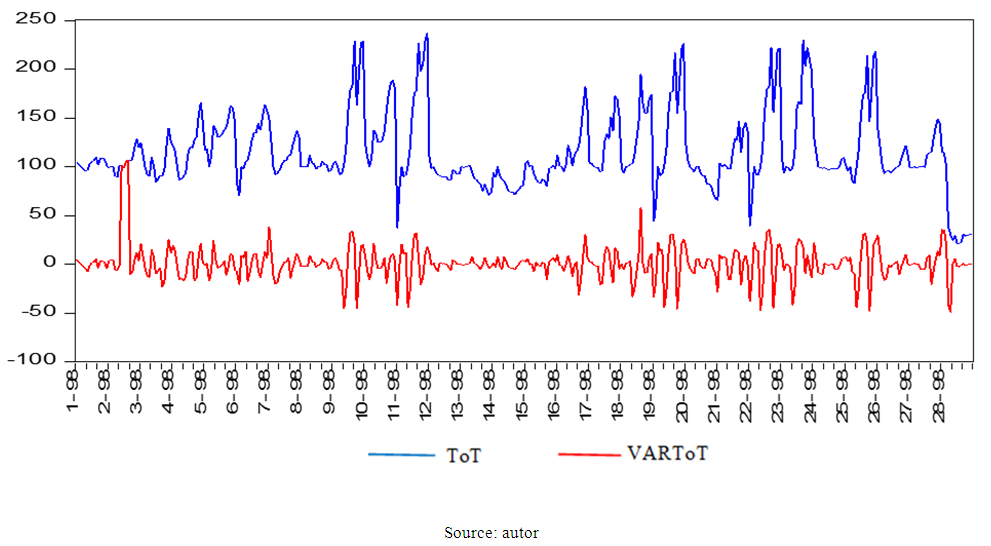

- In general, it can be seen that the countries with the lowest growth rates have high terms-of-trade variability, high population growth and high inflation rates. As for the correlation relations, it shows a positive correlation coefficient between growth and variability in terms of trade. This trend seems to be confirmed by observing the evolution of the three variables together in the following graph, which relates the trend in ToT, their volatility and growth. This matrix also shows the absence of a strong correlation between the explanatory variables.

| Figure 2. Joint evolution of ToT, their variability and growth in SSA |

4. Modeling

4.1. Specification of the Theoretical Model

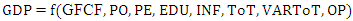

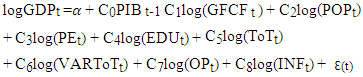

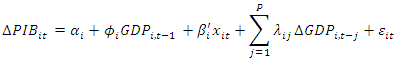

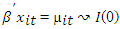

- Drawing on previous work, in particular that of [28] and [11], we use the analytical framework of a Solow growth model extended by [30] to assess the effect of ToT variability on growth. Indeed, [30] take up the foundations of Solow's model, incorporating the concept of human capital. Two types of capital are then included: physical capital and human capital, in order to better account for the unfolding of economic growth. This is justified by the fact that human capital can be increased by investing in the education system, the healthcare system and so on.So, to the variables of the [30] augmented growth model, we add our variables of interest, i.e. the terms of trade index (and its variability) and other variables likely to influence growth. These include:- economic policy variables: public spending and inflation rate- degree of openness to the outside worldThe theoretical model is thus as follows:

In the model, we use real GDP as the endogenous variable. Gross domestic product (GDP) measures the value added in an economy over a period of time or, equivalently, the income (or expenditure) arising from production activities. The rate of change of GDP measures growth. The estimates will focus on the dynamic model, where we introduce into the growth model a lagged value of the dependent variable to account for the dynamics of the GDP growth rate.For the variables we retain:- the ratio of investment measured by gross capital formation (GFCF) to GDP as a proxy for the stock of physical capital. As investment is the engine of growth, its expected effect on GDP is positive.- POP (Population active): the quantity of labor supplied in an economy is proportional to the working population, which is assumed to have a positive influence on production. In our model, we use the population aged 15 to 64.- PE (Public Expenditure): in the perspective of endogenous growth theory [31], public expenditure is a determinant of growth. They have a positive influence on growth.- EDU (human capital): Endogenous growth theory suggests a positive relationship between human capital and economic growth [32]. Indeed, human capital accumulation boosts factor productivity by increasing a country's capacity for innovation, enabling a better allocation of resources and generating positive externalities. The level of overall factor productivity depends on the level of human capital.- INF (Inflation rate): the idea is that sustainable, healthy economic growth can only be achieved in an environment of controlled price evolution. Nevertheless, the link between inflation and economic growth could be reversed below a certain inflation threshold, so there would be a non-linear relationship between inflation and economic growth.- OP (degree of openness to the outside world): as world trade provides comparative advantages and economies of scale (comparative advantage theory), involvement in world trade should generate additional growth. This variable should therefore have a positive effect. Openness is measured by the ratio: (exports + imports)/GDP over the period.- The terms of trade index (ToT): ratio of export prices to import prices. ToT is assumed to have a positive effect on economic growth, insofar as it is likely to boost domestic supply, thereby increasing the economy's capacity to respond to foreign demand. What's more, the process of increasing competitiveness that it suggests, in addition to foreign exchange gains and increased national savings, may prove favorable to economic growth. A change in the terms of trade index is assumed to have a positive effect on economic growth, insofar as it is likely to boost domestic supply, thereby increasing the economy's ability to respond to foreign demand. What's more, the process of increasing competitiveness that it suggests, in addition to foreign exchange gains and increased national savings, may prove favorable to economic growth.- VARToT (Variability of the Terms of Trade Index (base 2000)): This variable is measured by the standard deviation of the ToT (the difference between the ToT and the 5-year moving average). The expected sign of this variable is negative, as the permanent variability of the ToT could constitute a handicap for trade due to the uncertainty it induces on yields:- price variability leads exporters to arbitrate between the quantities offered and the risk associated with these sales. It leads them to set their export offer as a function of increasing expected profitability and decreasing export price variability. The variability of import prices introduces uncertainty into the costs of imported equipment and raw materials, reinforcing the uncertainty of yields and therefore limiting the supply of risk-averse producers.Assuming that economic growth in the current period can be determined by past performance, the one-period lagged endogenous variable is included as a regressor in the model.The model to be estimatedStarting from the above theoretical model, the equation to be estimated is written as follows:

In the model, we use real GDP as the endogenous variable. Gross domestic product (GDP) measures the value added in an economy over a period of time or, equivalently, the income (or expenditure) arising from production activities. The rate of change of GDP measures growth. The estimates will focus on the dynamic model, where we introduce into the growth model a lagged value of the dependent variable to account for the dynamics of the GDP growth rate.For the variables we retain:- the ratio of investment measured by gross capital formation (GFCF) to GDP as a proxy for the stock of physical capital. As investment is the engine of growth, its expected effect on GDP is positive.- POP (Population active): the quantity of labor supplied in an economy is proportional to the working population, which is assumed to have a positive influence on production. In our model, we use the population aged 15 to 64.- PE (Public Expenditure): in the perspective of endogenous growth theory [31], public expenditure is a determinant of growth. They have a positive influence on growth.- EDU (human capital): Endogenous growth theory suggests a positive relationship between human capital and economic growth [32]. Indeed, human capital accumulation boosts factor productivity by increasing a country's capacity for innovation, enabling a better allocation of resources and generating positive externalities. The level of overall factor productivity depends on the level of human capital.- INF (Inflation rate): the idea is that sustainable, healthy economic growth can only be achieved in an environment of controlled price evolution. Nevertheless, the link between inflation and economic growth could be reversed below a certain inflation threshold, so there would be a non-linear relationship between inflation and economic growth.- OP (degree of openness to the outside world): as world trade provides comparative advantages and economies of scale (comparative advantage theory), involvement in world trade should generate additional growth. This variable should therefore have a positive effect. Openness is measured by the ratio: (exports + imports)/GDP over the period.- The terms of trade index (ToT): ratio of export prices to import prices. ToT is assumed to have a positive effect on economic growth, insofar as it is likely to boost domestic supply, thereby increasing the economy's capacity to respond to foreign demand. What's more, the process of increasing competitiveness that it suggests, in addition to foreign exchange gains and increased national savings, may prove favorable to economic growth. A change in the terms of trade index is assumed to have a positive effect on economic growth, insofar as it is likely to boost domestic supply, thereby increasing the economy's ability to respond to foreign demand. What's more, the process of increasing competitiveness that it suggests, in addition to foreign exchange gains and increased national savings, may prove favorable to economic growth.- VARToT (Variability of the Terms of Trade Index (base 2000)): This variable is measured by the standard deviation of the ToT (the difference between the ToT and the 5-year moving average). The expected sign of this variable is negative, as the permanent variability of the ToT could constitute a handicap for trade due to the uncertainty it induces on yields:- price variability leads exporters to arbitrate between the quantities offered and the risk associated with these sales. It leads them to set their export offer as a function of increasing expected profitability and decreasing export price variability. The variability of import prices introduces uncertainty into the costs of imported equipment and raw materials, reinforcing the uncertainty of yields and therefore limiting the supply of risk-averse producers.Assuming that economic growth in the current period can be determined by past performance, the one-period lagged endogenous variable is included as a regressor in the model.The model to be estimatedStarting from the above theoretical model, the equation to be estimated is written as follows: With

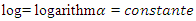

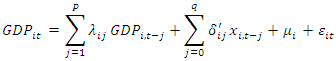

With  The above model specified in panel data gives the equation below:

The above model specified in panel data gives the equation below: Where i = country i = countryt = period (year)

Where i = country i = countryt = period (year) = the specific individual effectC1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7, C8 are the parameters to be estimated in this model.Ɛ(it) = is the error term

= the specific individual effectC1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7, C8 are the parameters to be estimated in this model.Ɛ(it) = is the error term4.2. Nature and Source of Data

- The data used in this study are secondary and quantitative. To ensure data consistency, we prefer to use data extracted from the World Bank database (World Development Indicators) covers the entire period and all countries. The choice of period and number of countries is justified by the availability of all data over the period, given that we are using a cylindrical panel.

4.3. Preliminary Tests

4.3.1. Unit Root Tests

- Prior to any regression on time series, it is necessary to study the stationarity of the variables in order to avoid the risk of spurious regression. The test frequently used, even when the time dimension is limited, is that of [33], who propose tests to detect the presence of unit roots. The basic equation of the IPS unit root test is as follows:

i = 1, 2,... N; t = 1, 2,... T,𝛼𝑖 is the individual fixed effectThe IPS test statistic is based on the individual mean of the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) statistics and can be presented as follows:

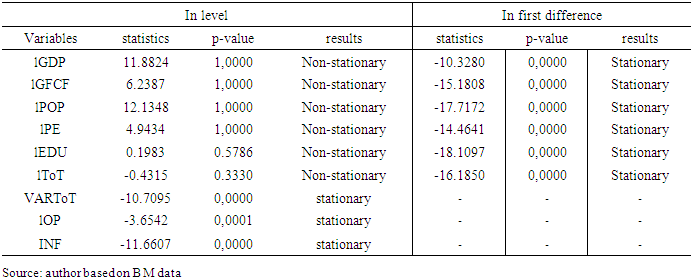

i = 1, 2,... N; t = 1, 2,... T,𝛼𝑖 is the individual fixed effectThe IPS test statistic is based on the individual mean of the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) statistics and can be presented as follows: Where tiT is the ADF statistic based on country-specific regression. The stationarity test revealed that not all variables are stationary in level. The results of the unit root tests (Table 1) show that, at the 5% threshold, only the variables VARToT, lOP and INF are stationary in level, i.e. integrated of order 0 (I(0)), while the other variables are non-stationary in level but stationary in first difference, i.e. integrated of order 1 (I(1).

Where tiT is the ADF statistic based on country-specific regression. The stationarity test revealed that not all variables are stationary in level. The results of the unit root tests (Table 1) show that, at the 5% threshold, only the variables VARToT, lOP and INF are stationary in level, i.e. integrated of order 0 (I(0)), while the other variables are non-stationary in level but stationary in first difference, i.e. integrated of order 1 (I(1).

|

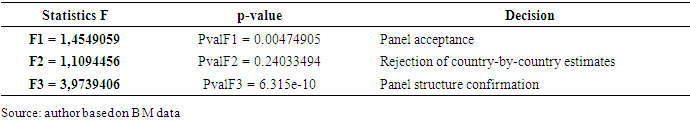

4.3.2. Overall Homogeneity Test

- Considering a sample of panel data, the first step to establish for this type of data is to check the homogeneous or heterogeneous specification of the data-generating process. We start by testing the hypothesis of a perfectly homogeneous structure (identical constant and slope).

|

4.3.3. Cointegration Test

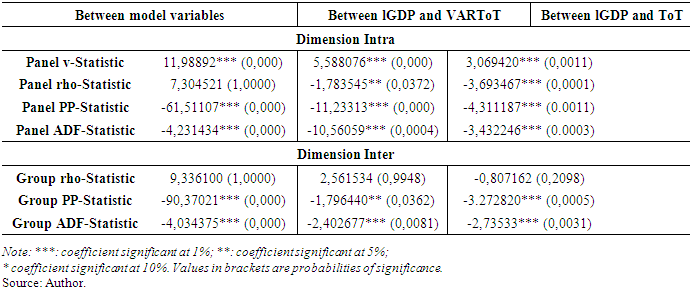

- We now test the existence of a cointegrating relationship between GDP, ToT and ToT variability. Two types of cointegrating relationships can be envisaged. Firstly, we can consider the existence of cointegrating relationships among the variables in the vector x it, which could be described as intra-individual cointegrating relationships. We say that one or more cointegrating relationships exist in the vector xit if and only if one or more linear combinations of the variables are stationary. Formally, for individual i, there are ri cointegrating relationships if and only if:

.We use [34] cointegration tests. Pedroni proposed various tests to capture the null hypothesis of no intra-individual cointegration for both homogeneous and heterogeneous panels. Like the unit root tests of [34], Pedroni's tests take heterogeneity into account through parameters that may differ between individuals. Of the seven tests proposed by Pedroni, four are based on the within dimension and three on the between dimension. Both categories of tests are based on the null hypothesis of no cointegration.The cointegration of variables depends on the value of the probability associated with each test statistic. Thus, with the exception of the Panel rho-Statistic and Group rho-Statistic, all other statistics reject the null hypothesis of non-cointegration. [34] cointegration tests (Table 3) prove that there is a cointegrating relationship between the variables. Based on these results, we can conclude that the data are cointegrated and that there is a long-term relationship between real GDP, ToT and terms-of-trade variability, at panel level. The next step is to estimate this long-term relationship.

.We use [34] cointegration tests. Pedroni proposed various tests to capture the null hypothesis of no intra-individual cointegration for both homogeneous and heterogeneous panels. Like the unit root tests of [34], Pedroni's tests take heterogeneity into account through parameters that may differ between individuals. Of the seven tests proposed by Pedroni, four are based on the within dimension and three on the between dimension. Both categories of tests are based on the null hypothesis of no cointegration.The cointegration of variables depends on the value of the probability associated with each test statistic. Thus, with the exception of the Panel rho-Statistic and Group rho-Statistic, all other statistics reject the null hypothesis of non-cointegration. [34] cointegration tests (Table 3) prove that there is a cointegrating relationship between the variables. Based on these results, we can conclude that the data are cointegrated and that there is a long-term relationship between real GDP, ToT and terms-of-trade variability, at panel level. The next step is to estimate this long-term relationship.

|

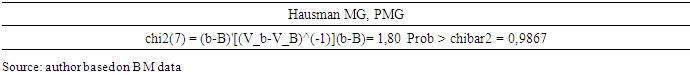

4.3.4. Hausman Test

- The PMG and MG methods can be used to estimate the long-term relationship. The fundamental difference between this estimator and the PMG estimator lies in the constraints imposed on the coefficients. For this reason, the Hausman test should be performed to confirm the suitability of the PMG estimator.

|

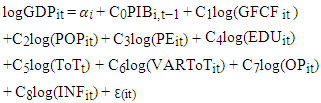

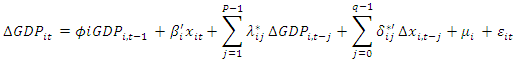

4.4. Estimation Method

- We use the Pooled Mean Group method of [35], a dynamic panel estimation technique designed to take account of the temporal dynamics that can exist in series. The "pooled mean group" (PMG) method avoids the need to average the data and thus gives much greater precision to estimates. It does, however, limit serial correlation problems by explicitly modeling short-term effects (by integrating first differences of independent variables), which may vary from country to country, as well as long-term effects, whose equality is imposed. The model postulated by [35] is the ARDL (Autoregressive Distributed Lag) model, as follows:

where

where  is a matrix of explanatory variables,

is a matrix of explanatory variables,  represents individual fixed effects,

represents individual fixed effects, are coefficients assigned to lagged dependent variables and

are coefficients assigned to lagged dependent variables and  is a matrix of scalars.The following specification is used to parameterize the long-term equation:

is a matrix of scalars.The following specification is used to parameterize the long-term equation:

4.5. Presentation and Interpretation of Results

4.5.1. Pooled Mean Group (PMG) Estimation Results

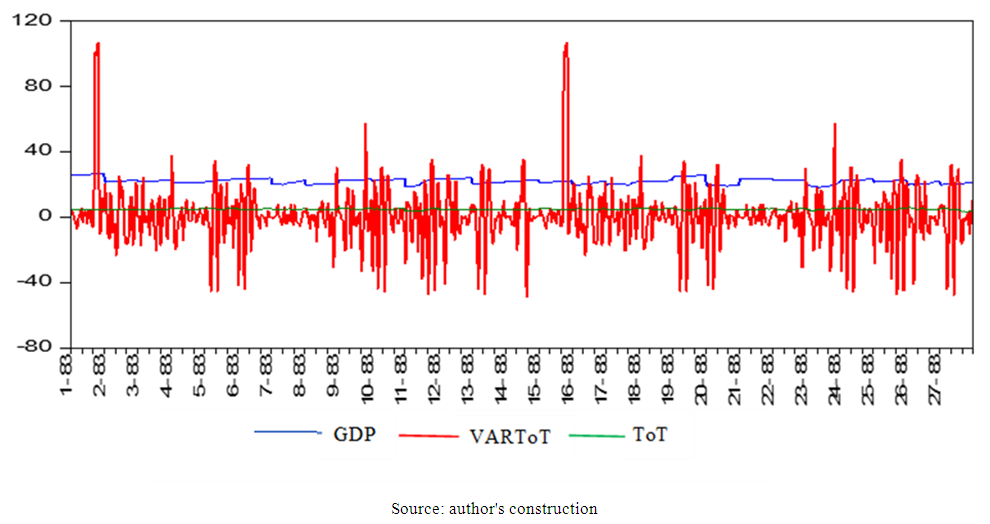

- Using the panel data method for 27 countries (appendix) in sub-Saharan Africa and over the period 1983-2012, the estimation results are presented in the table below.

|

4.5.2. Interpretation and Discussion of Results

- The adjustment parameter is negative and significant. The estimated mean coefficient associated with the error-correction term is negative and significant at the 5% level, confirming a long-run equilibrium relationship between ToT, terms-of-trade variability and economic growth across all countries.At the individual variable level, estimation using the Pooled Mean Group method shows that the coefficients associated with gross fixed capital formation, terms of trade, terms of trade variability and inflation exhibit the expected signs and are statistically significant at the 5% level. While primary education, public spending and openness have no significant influence on growth. Labour force growth, on the other hand, shows a negative and significant sign, but at the 5% threshold.The estimated coefficient of the variability of the terms of trade is negative and statistically significant, which also shows that there is a negative relationship between the variability of the terms of trade and economic growth in Sub-Saharan African countries at the 5% threshold, thus confirming our hypothesis. When the standard deviation of the ToT varies by 1%, growth is reduced by 0.11%. According to [25], the volatility of export prices affects growth by disrupting the macro-economic management of countries, discouraging domestic and foreign private investment and maintaining the vulnerability of African economies. Our results are also in line with previous studies, in particular those by [14], [34], [26], [25].The effects of ToT variability on growth can be seen at several levels:• Price variability leads exporters to arbitrate between the quantities offered and the risk associated with these sales. It leads them to set their export offer as a function of increasing expected profitability and decreasing export price variability [34];• The variability of import prices introduces uncertainty into the costs of imported equipment and raw materials, reinforcing the uncertainty of yields and therefore limiting the supply of risk-averse producers.

5. Conclusions

- The aim of this article was to analyze the influence of terms of trade variability on economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. To do this, we used panel data for 27 countries in the region, covering the 30-year period from 1983 to 2012. After preliminary tests, the model was estimated using the Pooled Mean Group method.The results showed that terms-of-trade variability has a negative impact on growth, while the terms-of-trade trend has a positive impact on growth, supporting the idea that terms-of-trade deterioration and high volatility are an obstacle to growth. In short, these results support our hypotheses. Since the variability of the terms of trade has a negative impact on growth, SSA countries need to contain the variability of the terms of trade as much as possible, or cope with its deterioration, since the products traded are of different types, and the terms of trade are difficult to stabilize. In this respect, it is necessary to intensify the process of diversifying exports, while forging ahead with the transformation of primary products into manufactured goods, improving the competitiveness of local economies and strengthening the structures needed to integrate Sub-Saharan Africa into international trade.

Appendix

- List of countries concerned

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML