Georges Richa1, Amal Abou Fayad2

1Ph.D Condidate at HOLLY SPIRIT UNIVERSITY of Kaslik-USEK, Faculty of Business Administration, Lebanon

2Lebanese University, Doctoral School of Law and Political, Administrative and Economic Sciences, Sin El Fil, Beirut, Lebanon

Correspondence to: Amal Abou Fayad, Lebanese University, Doctoral School of Law and Political, Administrative and Economic Sciences, Sin El Fil, Beirut, Lebanon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The balance of payments is an accounting and financial record in which all economic transactions related to countries are documented. Every country in the world has its own balance of payments that it uses to record financial transactions with other countries. It consists of two sections: a debit side, where financial transactions paid out are recorded, and a credit side, where financial transactions received are documented over a specific period, usually one fiscal year. A deep understanding of the indicators of balance of payments imbalances is not sufficient on its own. What is more important is taking practical actions to address these imbalances, focusing on the nature, seriousness, and effectiveness of these measures. This is particularly crucial in developing economies, where numerous challenges arise from existing economic and monetary policies, reliance on cash economies, rigid exchange rates, market instability, and excessive speculation. These factors make it difficult to implement preventive measures that could avert financial collapse and insolvency, as occurred in Lebanon starting from late 2019. The current article aimed to explore the balance of payments in Lebanon by examining its significance, balance, the reasons for the deficit, and the implications of this deficit on the country’s economic reality. Finally, the study presented a questionnaire about the extent to which the Lebanese people tend to consume imported or local goods, and the extent to which local companies are able to export or prefer to trade in foreign goods over local goods, or vice versa.

Keywords:

Lebanon, Balance of Payments, Asset Drainage, Import Reduction, Export Increase, Investment Growth

Cite this paper: Georges Richa, Amal Abou Fayad, The Lebanese Balance of Payments: Causes of the Deficit and Remedies, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20251501.01.

1. Introduction

Foreign trade holds significant importance for all countries, whether developed or developing. It plays a vital and effective role in the economies of nations, especially advanced ones, as it constitutes a substantial part of their national income [1]. This is due to the large production surplus that such economies experience, which they need to export to foreign markets. Additionally, foreign trade enables these economies to acquire the economic resources they require from other countries, ensuring the continuity of production processes and maintaining their rates of economic and social development [2].Developing countries, too, have an urgent need for foreign trade. It provides access to essential technology, manufactured goods, and semi-manufactured products required for their development programs. Furthermore, these countries increasingly depend on foreign trade to secure essential goods, particularly food items, which many are unable to produce sufficiently to meet their domestic market demands. As a result, they rely heavily on global markets for these necessities. Additionally, many nations rely on exporting raw materials to foreign markets [3].Economic transactions between countries lead to mutual financial obligations that must be settled immediately or in the future. Therefore, it is crucial for each country to precisely identify its rights and obligations concerning the outside world. For this purpose, countries prepare a statement or accounting record to document their rights and obligations. This statement is known as the "Balance of Payments." The Balance of Payments is essentially an account that records the value of rights and debts arising from exchanges and transactions between residents of a particular country and those abroad, whether these involve the purchase or sale of goods or services. It also includes details on capital and other expenditures over a specific period, typically one year, starting on January 1 and ending on December 31 [4].The Balance of Payments is of great importance. By studying its components, it reflects the degree of economic progress in a country and allows for assessing its financial position relative to the global economy. For this reason, the International Monetary Fund often requires all its member countries to submit their annual Balance of Payments, as it is one of the most precise indicators for evaluating a country's external financial standing [5].This article is exploratory and focuses on the Balance of Payments in Lebanon prior to the current economic crisis. It will highlight its significance, status, the causes of the deficit, the implications of this deficit, and finally, present proposals to address the deficit.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Balance of Payments: Definition and Context

The concept of the BoP has been central to economic theory and policy since the mercantilist period, when nations sought to maximize exports and minimize imports to accumulate wealth. With the evolution of international trade and finance, economists like David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill introduced the theory of comparative advantage and its relationship with trade balances [6]. In modern economics, the BoP is analyzed not only as an accounting tool but also as a diagnostic instrument for economic health.The Balance of Payments has several definitions, the most notable of which include:• "It is a record of all economic transactions between a country's residents and the rest of the world during a specific period of time." [7]• The International Monetary Fund (IMF) defines it as a set of accounts systematically recorded over a specified period, as follows:- The value of tangible products, including services derived from primary production factors, exchanged between the domestic economy of a given country and other countries worldwide.- Changes resulting from economic transactions affecting a country’s assets.- One-sided transfers, whether provided or received, in terms of resources or financial debts between the country and the rest of the world.• The Balance of Payments is also defined as "an officially documented accounting or statistical record based on double-entry bookkeeping, summarizing receipts and payments that result in credit rights and debt obligations for the residents, whether natural or legal persons, of a given country in relation to foreign parties. This is a result of economic exchanges and external transactions, whether unilateral or bilateral, over a specific period." [8]

2.2. The Importance of the Balance of Payments

The Balance of Payments is considered one of the most critical measures for determining a country’s economic status, whether in prosperity or financial deficit [7]. It offers numerous benefits, which can be summarized as follows:• Provides comprehensive details about the national economy, external economies, the nature of their relationships, and the degree of interconnection, highlighting a country's position in the global economy.• Supports decision-making by enabling policymakers to devise and implement appropriate economic policies.• Serves as a key tool for interpreting and analyzing various economic phenomena scientifically, particularly those related to the global economy.• Assists governments in forecasting and estimating currency exchange rates in financial markets through the analysis of trade volumes and types of exchanged goods.• Enables assessment of the economic situation of a country over short periods by examining and measuring its Balance of Payments.• Reflects the strength and competitiveness of the national economy through the transactions recorded in the Balance of Payments. It also indicates the economy’s responsiveness to international changes by highlighting the scale and structure of production and factors influencing it, such as investment levels, employment rates, pricing and cost levels, as well as technological and scientific advancements.Therefore, the Balance of Payments is one of the most significant financial indicators used to assess a country’s financial status. It is heavily relied upon by credit rating agencies for financial evaluations, it holds great importance in assessing the economic [9].

2.3. Components of the Balance of Payments

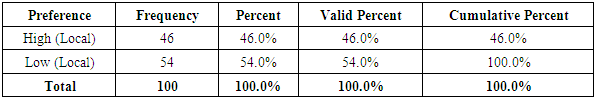

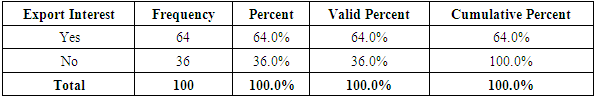

In the past, countries operated under the assumption that the Balance of Payments consisted solely of goods exports and imports. Its structure was as follows:• The first side, called the "Debit", recorded all financial transactions involving payments made.• The second side, called the "Credit", recorded all financial transactions involving payments received [8].However, with global advancements and the ease of investment exchange through stock markets, this concept evolved. Consequently, the Balance of Payments now comprises two main components: | Figure 1 |

1. Current Account (or Current Transactions): This account records a country’s exports and imports of goods and services, as well as unilateral transfers and all financial flows to and from the economy. It comprises the following components:• Trade Balance: Includes all trade transactions, which are further divided into two subcategories:ο Goods Balance: Records the export and import of goods.ο Services Balance: Records services exchanged between countries, such as transportation, labor visas, and others.• Unilateral Transfers: This account records credit and debit transactions conducted by one party only (i.e., for the benefit of the state alone). Separate unilateral accounts are created for other countries involved in transactions [1].2. Capital Account: This account focuses on recording capital movements between a country and its trade partners, leading to the identification of credit and debit positions in financial dealings. The capital account is divided into three subaccounts:• Short-term Capital: This account consolidates all financial movements related to assets and liabilities of residents and non-residents, with a duration of no more than one fiscal year. Examples include short-term bank loans and international payment agreements.• Long-term Capital: This account consolidates financial movements related to assets and liabilities of residents and non-residents, with a duration exceeding one fiscal year. Examples include investments in financial portfolios and commercial loans tied to imports and exports.• Deposits: This account includes financial movements related to deposits in foreign and local currencies, as well as the exchange rates of currencies relative to gold prices [5].

2.4. Factors Affecting the Balance of Payments

Several factors, both internal and external, can impact the Balance of Payments. Key influences include monetary inflation, changes in GDP growth rates, variations in interest rates, and fluctuations in foreign exchange rates relative to the national currency.1. Internal Factors:• Inflation: Persistent inflation reduces the competitiveness of national exports, decreases the trade balance surplus, and increases the deficit, thereby exerting pressure on the Balance of Payments.• GDP Growth Rate: An increase in a country's income typically leads to higher demand for imports, whereas a decline in income reduces import demand.2. External Factors:• Interest Rate Differences: Under normal conditions, changes in interest rates, whether rising or falling, directly influence capital flows. Higher domestic interest rates attract foreign capital inflows, while lower interest rates make global financial markets more appealing to investors.• Exchange Rate: When foreign exchange rates rise, the competitiveness of locally produced goods and services declines, making imports more attractive due to their comparatively lower prices. Conversely, a decrease in the exchange rate enhances the competitiveness of exports, while imported goods and services become less appealing to residents due to higher relative prices.

2.5. Lebanese Balance of Payments

After addressing the theoretical framework of the balance of payments in general, the following presents the balance of payments of Lebanon, the reasons behind its deficit, and the implications of this deficit.

2.5.1. The Balance of Payments of Lebanon

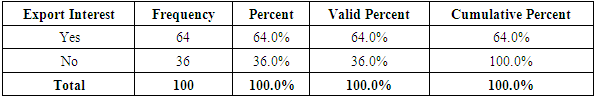

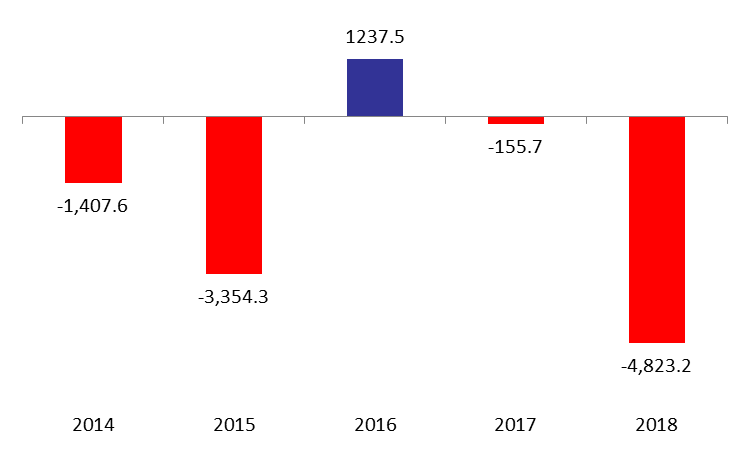

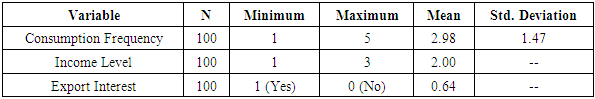

The slowdown in financial flows, capital movements, and both direct and indirect investments, coupled with a decline in incoming capital flows, significantly impacted Lebanon's balance of payments. Since 2011, the balance of payments has consistently recorded deficits, accumulating to a total of approximately $8.3 billion over seven years by the end of 2017. The exception was in 2016, which saw a surplus of $1.2 billion, driven by the massive financial engineering operations conducted by the Central Bank of Lebanon (BDL) in collaboration with commercial banks. These operations cost public finances around $5.6 billion, providing extraordinary profits (around 40%) to banks and their major depositors on their dollar investments [10].In 2017, the balance of payments deficit stood at $155.7 million, the lowest recorded deficit compared to previous years. However, this improvement did not result from increased inflows of hard currency into Lebanon. Instead, it was a result of a recalculation by the Central Bank. Starting in November 2017, the Central Bank decided to include approximately $1.7 billion in its net foreign assets. This amount represented an accounting operation with the Ministry of Finance, whereby treasury bonds in Lebanese pounds held by the Central Bank were swapped for dollar-denominated bonds. No actual cash transfer occurred between the Ministry and the Central Bank as part of this process [11].Lebanon’s Balance of Payments by December (in millions of $) Source: BDL | Figure 2 |

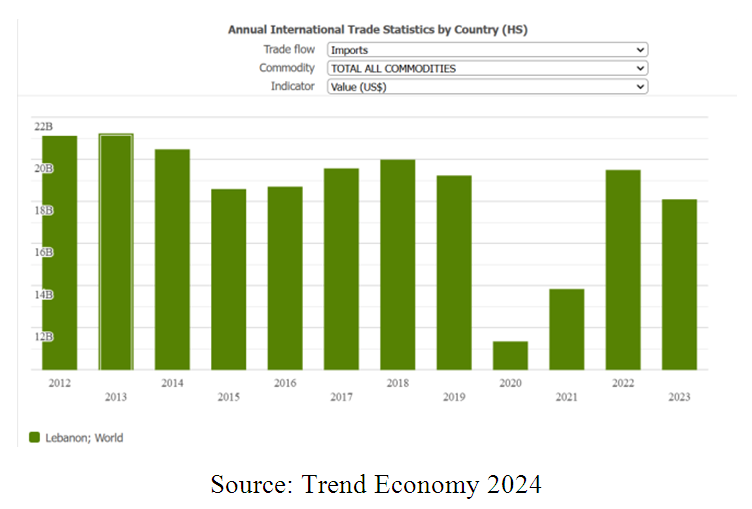

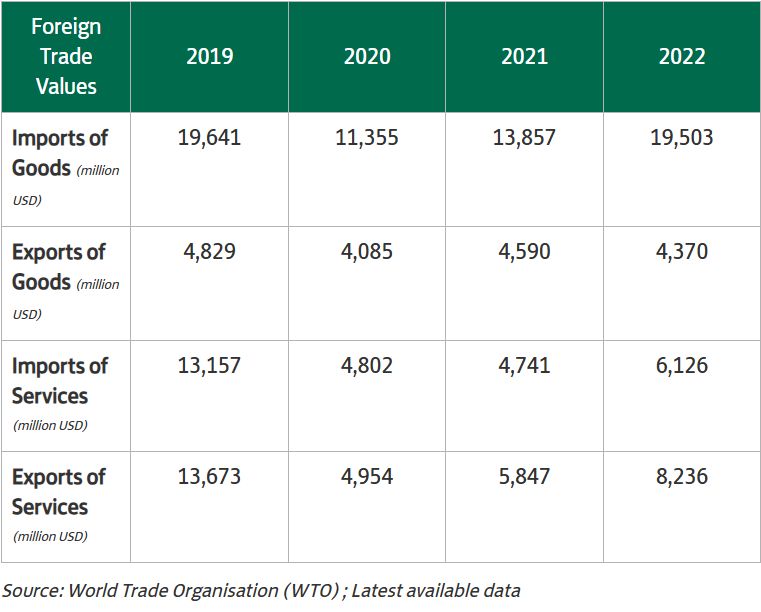

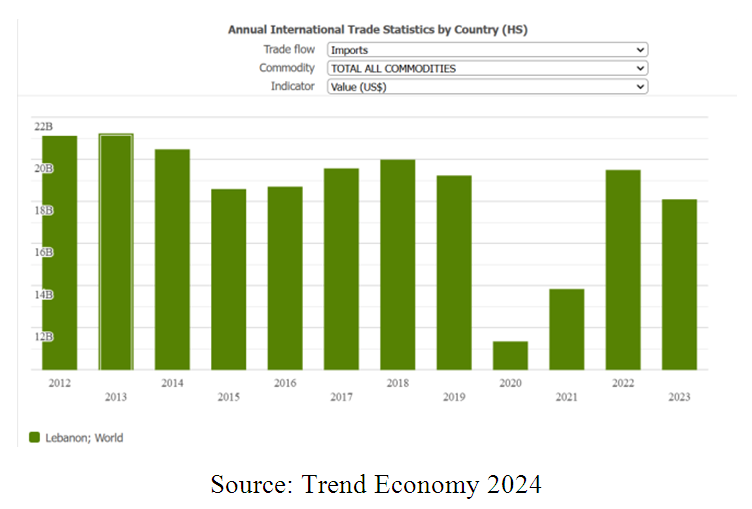

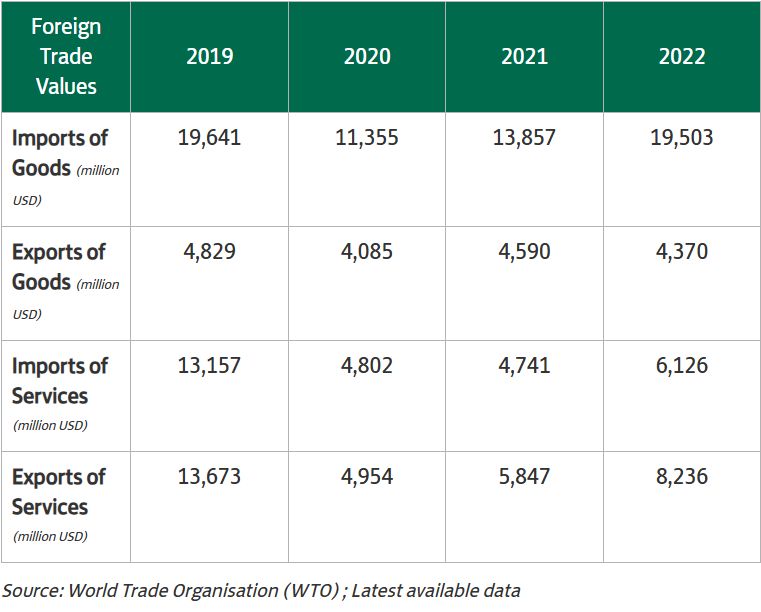

This implies that the actual deficit in the balance of payments was significantly higher than what was officially reported in the statistics. For instance, the balance of payments recorded a deficit of $887.8 million in October 2017 compared to a surplus of $67.4 million in November 2017. This discrepancy highlights the reliance on accounting practices rather than genuine financial inflows to mitigate the reported deficit [6].Before implementing capital control measures, Lebanon had been experiencing a continuous negative balance of payments since 2011. This shift was primarily due to the decline in the capital account and the inability to offset the enormous trade deficit, which exceeded $17 billion annually. By the end of 2019, the balance of payments recorded a deficit of $4.351 billion, bringing the cumulative deficit from 2011 to July 2020 to $14.5159 billion. The exception was 2016, when no deficit was recorded due to the financial engineering operations by the Central Bank of Lebanon, which attracted foreign capital through participating Lebanese banks to purchase Eurobonds in foreign currencies [11].It is worth noting that since 1993, the growth gap between foreign currency deposits and the external assets of the banking system has gradually widened. As the US dollar is not used solely for import payments, the amount of foreign currency deposits no longer equals the quantity of foreign currency assets. Two other factors have contributed to this gap: the continuous conversion of Lebanese pounds to US dollars and banks issuing loans in dollars, which increase money creation. Additionally, the use of the dollar for local transactions as a payment and settlement tool has also played a role [12]. A structural analysis of Lebanon’s balance of payments reveals that the trade balance has recorded a massive deficit for decades, reflecting the near-total incapacity of the economic machinery to meet domestic demand.Regarding the export and import of services, data from the International Trade Center (ITC) for 2014 indicates that the services balance is roughly neutral, with imports and exports each valued at about $13 billion. Transfers from international organizations and profit repatriation remain minimal in both directions, resulting in an invisible transactions balance of approximately zero.As for the capital account, the data shows significant inflows into Lebanon, peaking at $20.7 billion in 2009 before declining to $11.8 billion in 2015. The Lebanese balance of payments generally maintained a surplus due to a consistently robust capital account.Remittances from expatriates peaked in 2013 at over $7.8 billion but dropped to $7.1 billion in 2015 due to falling oil prices. Foreign direct investment (FDI) also declined, from a high of $4.8 billion in 2009 to $2.34 billion in 2015, less than half its peak value [13].Non-resident and non-financial sector bank deposits reached $64.4 billion, with monthly variations averaging $400 million, resulting in an $18.4 billion increase in deposits since October 31, 2012.Finally, external loans and trust reserves are egligible overall, as they are rare and, when present, not recurrent. Thus, they can effectively be considered non-existent.

2.5.2. Trade Deficit

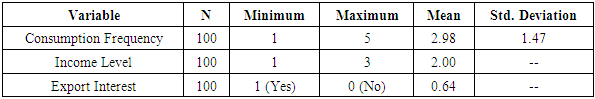

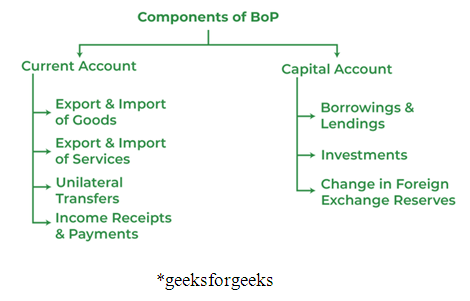

The trade deficit is a symptom of a deeper problem, as former Finance Minister Elias Saba puts it: "The deficit is the result, not the cause, and addressing it in isolation is not viable without a comprehensive solution." Saba questions: "What kind of imports are we talking about? The merchant importing the finest French cheese won't stop because their clientele can afford it and haven't changed their consumption habits." He adds, "Reducing imports impacts the middle and lower classes, crushing them." Thus, Saba argues that rationing imports is not the way to combat the balance of payments deficit, especially when local alternatives are scarce."How much agricultural land do we have, and what is our production capacity? Industrially, we lack mineral resources and raw materials," Saba notes. The absence of a productive economy capable of self-sufficiency and generating exports to bring in dollars is politically driven. The economic approach of some former prime ministers, he says, was based on exporting the country's best human resources while importing cheap labor. This approach created a financial and economic system that collapses without importing $10–12 billion worth of goods annually, "like a cyclist who falls over when they stop pedaling."Until 2011—when Lebanon began recording ten consecutive years of deficits in the balance of payments, reaching a cumulative $16.1 billion deficit between 2011 and 2018 (compared to surpluses of $25.4 billion between 2002 and 2010)—dollars were still flowing in because "our economy thrived on debt and the misfortunes of other economies."For this reason, Saba argues that halting imports to resolve the deficit would "send us back to the Middle Ages." Instead, efforts should focus on generating foreign currency by "developing the services sector and advancing technology-related industries as a form of productive economy where we excel." However, at its core, Lebanon must "learn how to build a state from scratch and define its identity and role. [14]"Decline in Imports Didn’t Prevent an Increase in the Balance of Payments Deficit Due to OutflowsIn 2020, Lebanon’s imports dropped to approximately $11 billion, down from $19 billion in 2019. Despite this reduction, the balance of payments recorded a deficit of $10.55 billion, compared to less than $6 billion in 2019. This initial finding indicates that the deficit is primarily due to financial outflows unrelated to imports, and reducing imports alone does not resolve the crisis [15].  | Figure 3 |

Conversely, the balance of payments deficit decreased to $1.812 billion in the first half of 2021. Meanwhile, the trade balance deficit reached $2.061 billion by March 2021. Recent financial policies have relied on multiple exchange rates, rationing letters of credit for importing medicine and fuel, and allowing the Lebanese pound to depreciate sharply. This collapse in the currency has eroded the purchasing power of residents, causing prices to skyrocket and reducing people’s ability to buy necessities. As a result, imports declined, reducing the dollars used for them.In 2020, the Central Bank of Lebanon’s dollar reserves fell by approximately $14.274 billion. Government estimates indicate that $6.4 billion of this amount was spent by the Central Bank on subsidized goods, including fuel for state electricity (a debt on the government paid in Lebanese pounds). The remaining $7.874 billion left the Central Bank to benefit influential bank owners, depositors, and foreign obligations.Attempting to correct the balance of payments deficit solely by slashing imports—without providing local alternatives—has led to further price increases, deeper economic contraction, reduced growth, higher unemployment, and increased poverty, all without securing additional dollars.A sustainable reduction in the balance of payments deficit and genuine reduction in dependence on foreign goods require a sound banking sector capable of financing long-term loans, encouraging investments, ensuring local alternatives, and increasing exports. During such crises, it is natural for imports to decline, but this should be seen as an opportunity to develop local production to meet market demands."The key to addressing the balance of payments deficit lies in increasing the production of goods, services, and technology," says former Economy Minister Mansour Bteish. "Boosting production provides alternatives to imported goods, reduces the trade deficit, and creates sources of income in dollars." | Figure 4 |

Bteish also advocates for "revisiting the tax system to ensure it serves the economy's objectives. Restoring balance to the trade deficit can be achieved by developing goods and services with comparative advantages and competitive capabilities, thereby ending the dependence on external economies."In conclusion, reducing imports alone is not the solution to the crisis [16].

2.5.3. The Impact of the Balance of Payments Deficit

1. Depletion of ReservesThe balance of payments reflects Lebanon’s external financial interactions with other countries. A surplus indicates a net inflow of foreign currency, whereas a deficit indicates a net outflow. A persistent deficit results in a growing shortage of foreign currency reserves. This forces Lebanon to rely on previously accumulated surpluses or stimulate new inflows of foreign currency.While this strategy can work short-term, it is unsustainable over time. Continued outflows risk [16] exhausting foreign reserves, especially given the significant financing needs for a $20 billion trade deficit. Compounding this problem is the decline in the trade deficit due to a sharper reduction in imports than in exports, which means Lebanon's savings from lower oil prices cannot fully compensate for the deficit.The balance of payments reveals the source of the foreign currency outflows. These outflows may originate from the Central Bank or private banks. The Central Bank may channel foreign currencies to banks, which could either retain the funds or transfer them abroad. However, when foreign currencies leave the banks and exit the country, it indicates capital flight—a major concern.If the volume of outflows exceeds inflows, the demand for foreign currency grows, eroding trust in the financial system. This declining trust perpetuates the crisis, increasing demand for dollars and exacerbating the outflow, creating a vicious cycle that is difficult to break [17].2. Rising Interest RatesIn response to the risks posed by the growing deficit in the balance of payments, banks raised interest rates, and the Central Bank implemented costly financial engineering schemes. The Lebanese government also resorted to borrowing heavily from foreign creditors and capital markets. Given Lebanon’s rentier, dollarized economy, weak exports, and escalating fiscal deficit, the Central Bank's need for additional foreign currency reserves intensified, primarily to service its debts. By June 2017, foreign currency deposits by banks at the Central Bank exceeded $53 billion, with an average interest rate of at least 5%. Consequently, the Central Bank incurred an annual interest expense of no less than $2.5 billion on dollar deposits alone.The balance of payments deficit underscores a critical weakness in Lebanon’s economic model, which relies heavily on external financing. This model not only lacks resilience but also entrenches dependence on foreign inflows, leading to rising domestic costs. Maintaining these inflows necessitates higher interest rates, which directly impact public debt costs. By 2018, Lebanon’s total public debt exceeded $110 billion, including $70 billion in government debt and an additional $40 billion owed by the Central Bank to banks.This unsustainable economic framework has contributed significantly to the ongoing financial crisis [10].

2.5.4. Suggestions for Addressing Balance of Payments Deficits

In general, there are two main approaches to correcting imbalances in the balance of payments:First Approach: Correction through Market MechanismsTraditional thought in this area relies on the price system to achieve external balance. Modern analysis expands this view to include the role of price and income changes in explaining external equilibrium, as well as incorporating financial operations to develop a comprehensive theory. This approach takes three main forms:1. Correction through Price MechanismsThis method is associated with the gold standard era and requires three basic conditions:• Fixed exchange rates.• Full employment of production factors in the country.• Price and wage flexibility (freedom of movement).These conditions form the foundation of the classical theory. The theory posits that gold movements are interdependent with the balance of payments. For instance [18]:• In case of a surplus: Large gold inflows increase the money supply, raising domestic prices compared to other countries. This results in decreased exports (due to higher domestic prices) and increased imports (due to lower foreign prices), restoring balance over time.• In case of a deficit: The reverse process occurs, leading to balance restoration.2. Correction through Exchange Rate AdjustmentsThis mechanism applies when the international gold standard is abandoned (e.g., during the fiat currency system between the World Wars). It involves adopting a floating exchange rate system.A country facing a balance of payments deficit often needs foreign currency and thus sells its local currency in foreign exchange markets. Increased supply of the local currency reduces its value. Consequently:• Domestic goods and services become cheaper compared to foreign goods, boosting exports.• Imports decline due to the higher relative cost of foreign goods. This process continues until balance is restored.3. Correction through Income AdjustmentsThis method is based on Keynesian theory, emphasizing income changes and their effects on foreign exchange and the balance of payments. Key conditions include [19]:• Fixed exchange rates.• Price rigidity.• The use of fiscal policy, particularly public spending, to influence income through the multiplier effect.A balance of payments surplus, for instance, leads to increased employment and wages in export industries, which raises incomes. Higher incomes spur demand for goods and services, including imports, which balances the payments.• In case of a deficit: Reducing public spending (e.g., via taxes) lowers income and aggregate demand, including demand for imports, decreasing foreign exchange demand and restoring balance.From these observations, public authorities can intervene using fiscal or monetary policies to restore balance in the economy, addressing inflation (due to a deficit) or economic recession (due to a surplus). These measures are termed stabilization policies.Second Approach: Correction through Government InterventionGovernments often do not leave market forces alone to restore balance due to concerns about price and income fluctuations, which may conflict with priorities such as price stability and full employment. In such cases, governments resort to various policies:Domestic Measures• Selling domestic stocks and bonds to foreigners to obtain foreign currencies.• Selling domestic real estate to foreigners for foreign currency.• Using trade policies (e.g., quotas or tariffs) to curb imports while promoting exports.• Utilizing gold reserves and international reserves to correct imbalances.External Measures• Seeking external loans from sources like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), foreign central banks, or international capital markets.• Selling a portion of the gold reserves abroad.• Selling stocks and bonds owned by public authorities in foreign institutions to citizens of those countries to acquire foreign currency.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

This study aims to assess:The extent to which Lebanese consumers prefer imported or local goods and the impact of these preferences on the balance of payments.The trading preferences of local companies, whether they favor foreign or local goods, and how this affects the balance of payments.The ability and willingness of local companies to export goods as a means to secure foreign currency and reduce the balance of payments deficit.To achieve these objectives, a mixed-method approach was employed, integrating quantitative (questionnaires) and qualitative (semi-structured interviews) methods for a comprehensive analysis.SamplingThe sample comprised two distinct groups:a. Lebanese Consumers: A random sample of 100 individuals, representing diverse demographics, was selected to capture varying consumption behaviors and preferences.b. Companies: A stratified sample of 50 companies was chosen, ensuring representation across small, medium, and large enterprises. These businesses operate in key sectors, including retail, industry, and services, providing a holistic view of trading and export tendencies.

3.2. Methods of Data Collection

Questionnaires- Consumers: A structured questionnaire was distributed to assess preferences for imported versus local goods. The survey included closed-ended questions and Likert-scale items (e.g., "Rate your preference for purchasing local goods on a scale of 1 to 5").- Businesses: Another questionnaire targeted financial managers of selected companies to explore their trading behaviors (local vs. foreign goods) and willingness to export goods. Questions assessed perceived challenges and benefits associated with these behaviors.- Semi-Structured Interviews Five economists with expertise in international trade and economic policy were interviewed. The interviews explored the broader implications of consumer and business behaviors on the balance of payments. Questions focused on the role of economic policies, trade dynamics, and potential strategies for improving Lebanon’s trade deficit.- Documentary Analysis: An analysis was conducted using reports from the Central Bank of Lebanon, international financial institutions, government policy documents, academic literature, and media coverage to examine the balance of payments dynamics in Lebanon. The findings revealed a persistent trade deficit due to limited local production and heavy reliance on imports, compounded by unsustainable financial practices such as reliance on remittances and financial engineering. The rigid dollarized financial system further exacerbates the crisis, while insufficient policy coordination to boost local production and exports has deepened socio-economic challenges like inflation, unemployment, and poverty. This analysis, combined with primary data, informs actionable recommendations to address the deficit.- Secondary Data:ο Secondary data were collected from reports by the Central Bank of Lebanon, international financial institutions, government policy documents, academic research, and media coverage to analyze Lebanon’s balance of payments dynamics. The analysis revealed a persistent trade deficit caused by limited local production and heavy reliance on imports, compounded by unsustainable financial practices such as reliance on remittances and financial engineering. The rigid dollarized financial system has worsened the crisis, while inadequate policy efforts to boost local production and exports have deepened socio-economic issues like inflation, unemployment, and poverty. This secondary data analysis complements primary research and informs practical recommendations for addressing the deficit.

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

Secondary data were collected from diverse sources, including reports from the Central Bank of Lebanon, international financial institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, government policy documents, academic research, and media coverage. These data provided a comprehensive understanding of Lebanon’s balance of payments dynamics, historical trends, and policy implications. Primary data were gathered through structured questionnaires targeting 100 Lebanese consumers and 50 companies across various sectors, focusing on import and export tendencies, as well as semi-structured interviews with five economists to explore in-depth perspectives on the economic situation. This mixed-method approach ensured a robust analysis by combining quantitative and qualitative insights.

3.4. Confidentiality and Anonymity

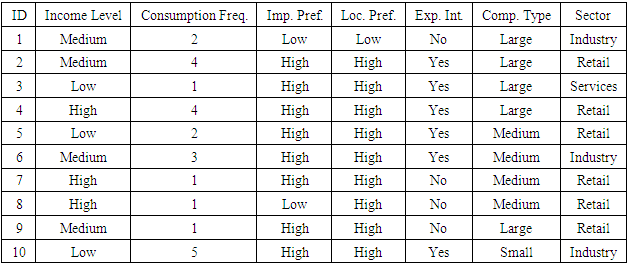

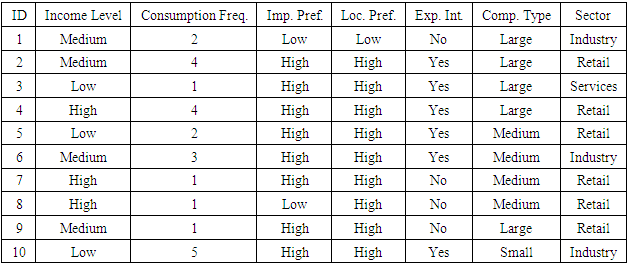

All participants in the study were assured of confidentiality and anonymity to encourage honest and accurate responses. Questionnaire data were anonymized, and identifiers such as names, business details, or personal information were excluded from the analysis. For interviews, pseudonyms were used, and recordings were securely stored with restricted access to researchers only. Ethical guidelines were strictly followed, ensuring that participants’ information was handled responsibly and their identities protected throughout the research process.Table 1. Sample

|

| |

|

Explanation of each variable:• ID: A unique number assigned to each participant to identify them in the dataset.• Import Preference: Indicates whether participants prefer imported goods (High) or not (Low).• Local Preference: Reflects the preference for locally produced goods (High) or not (Low).• Income Level: Categorizes participants based on their income level into Low, Medium, or High.• Consumption Frequency: Measures how often participants consume goods on a scale of 1 (low) to 5 (high).• Export Interest: Shows whether companies are interested in exporting their goods (Yes) or not (No).• Company Type: Describes the size of companies as Small, Medium, or Large.• Sector: Identifies the industry in which the company operates, such as Retail, Industry, or Services.

3.5. Data Processing

1- Data Cleaning:a. Ensured that all entries in the dataset were complete and free from errors.b. Checked for inconsistencies, such as mismatched values (e.g., invalid income levels or duplicate IDs), and corrected them.2- Data Coding:a. Coded categorical variables like "Income Level" (e.g., Low = 1, Medium = 2, High = 3) and "Export Interest" (Yes = 1, No = 0) for statistical analysis.b. Assigned numerical values to "Import Preference" and "Local Preference" for easier computation (High = 1, Low = 0).3- Data Transformation:a. Aggregated data by calculating the average consumption frequency across different sectors and income levels.b. Created derived variables such as the ratio of local preference to import preference for deeper analysis.4- Statistical Analysis:a. Imported the cleaned dataset into SPSS for descriptive statistics (means, medians, and frequencies).b. Conducted cross-tabulations to examine relationships between variables (e.g., income level vs. preference for local goods).c. Performed hypothesis testing using chi-square tests and regression models.5- Data Visualization:a. Prepared charts and graphs to illustrate trends in consumption patterns, preferences, and export interests.

3.6. Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1 (H1): There is a significant relationship between income level and the preference for imported goods.Hypothesis 2 (H2): Participants with higher consumption frequencies are more likely to prefer locally produced goods.Hypothesis 3 (H3): Companies in the retail sector are more inclined to export their goods compared to companies in the industry and services sectors.Hypothesis 4 (H4): A higher preference for local goods correlates with a lower interest in imported goods.Null Hypotheses (H0): There is no significant relationship between the variables tested in each hypothesis.

4. Results

This section presents the results obtained from the data analysis of Lebanon’s balance of payments and associated factors. The results are detailed using frequency tables and descriptive statistics for each variable studied.

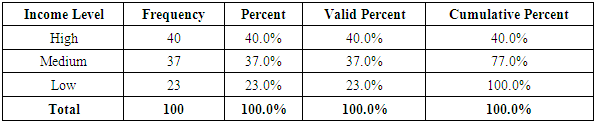

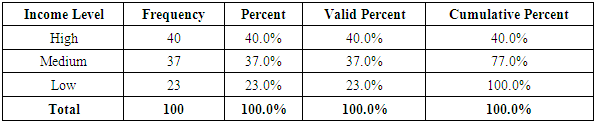

4.1. Income Level

The participants were classified into three categories based on income levels: low, medium, and high. The results indicate a balanced distribution, with 40% of participants classified as high-income, 37% as medium-income, and 23% as low-income.Table 2

|

| |

|

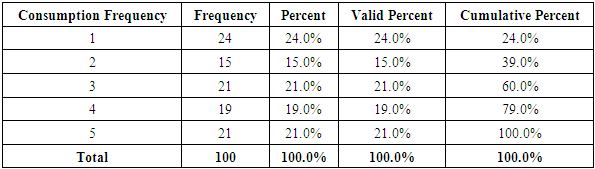

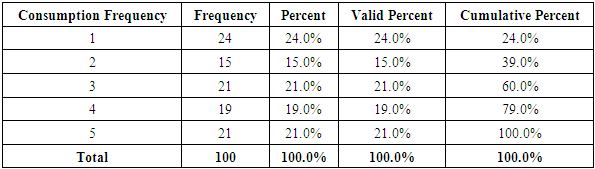

4.2. Consumption Frequency

Consumption frequency was measured on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represents the lowest and 5 the highest frequency. The results show a near-equal distribution, with 21% reporting the highest frequency (5), and 24% reporting the lowest frequency (1). The average consumption frequency is 2.98.Table 3

|

| |

|

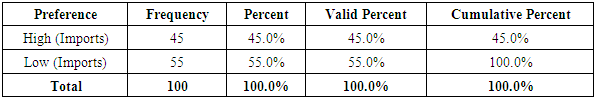

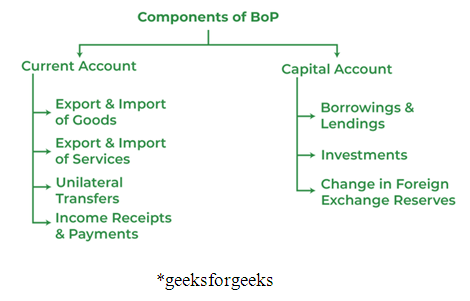

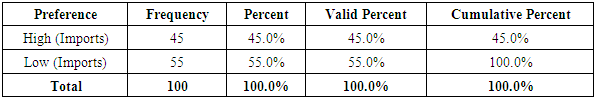

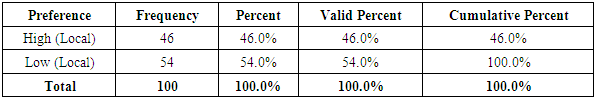

4.3. Import and Local Preferences

Preferences for imported and locally produced goods were analyzed. The results reveal that 55% of participants prefer local goods, while 45% favor imported goods. Similarly, 54% of participants expressed a preference for local goods, compared to 46% who preferred imports.Table 4

|

| |

|

Table 5

|

| |

|

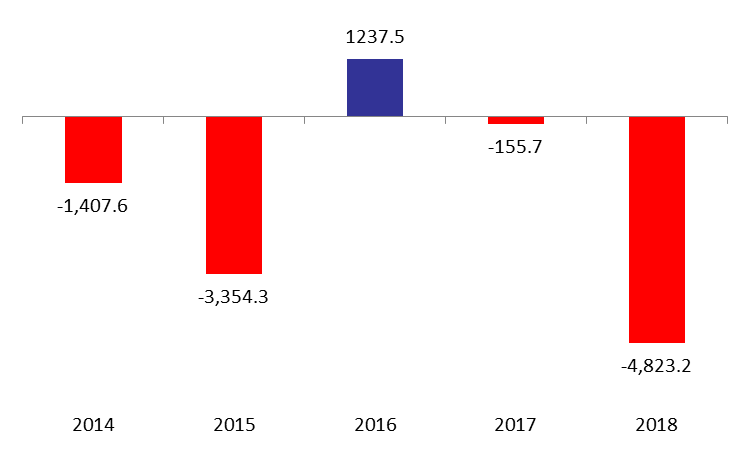

4.4. Export Interest

The level of interest in exporting goods was assessed. The results show that 64% of participants expressed interest in exporting, while 36% were not interested.Table 6

|

| |

|

4.5. Descriptive Statistics

The following table summarizes the descriptive statistics for key variables studied, including means and standard deviations.Table 7

|

| |

|

4.6. Analysis by Variable

• Income and Import Preferences: Participants with higher income levels showed a greater preference for imported goods, but this relationship was not statistically significant.• Consumption Frequency and Local Preferences: Participants with higher consumption frequencies tended to prefer local goods, though the trend was not significant.• Sector and Export Interest: Retail companies showed the highest interest in exporting, aligning with expectations for the sector.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of Lebanon's balance of payments and associated economic behaviors reveals critical trends and challenges. The findings indicate a balanced distribution among income levels, with a slight preference for locally produced goods over imported goods. However, a majority of companies expressed significant interest in exporting, particularly in the retail sector, highlighting opportunities for policy interventions to boost export-oriented activities. Despite these trends, statistical tests showed no significant relationships between income levels and preferences for imports, local goods, or export interest, underscoring the complexity of the underlying factors.Descriptive statistics highlighted moderate perceptions of compliance, non-compliance, and the perceived stringency of standards. Companies reported an average of 9.7 years of experience, reflecting their diverse operational histories. These insights emphasize the need for comprehensive policies aimed at reducing trade and balance of payments deficits by fostering local production, supporting exporters, and improving compliance with financial standards.To address Lebanon's economic challenges, the government must prioritize stabilizing the financial system, increasing local production capacity, and promoting export competitiveness. Efforts should focus on creating a sustainable economic model that reduces reliance on imports and enhances confidence in the financial and banking sectors. These measures are essential for mitigating the trade imbalance and ensuring long-term economic stability.

References

| [1] | Y. Jiang, «4 - Potential effects of foreign trade on development», in China, Y. Jiang, Éd., in Chandos Asian Studies Series. , Oxford: Chandos Publishing, 2014, p. 45-61. doi: 10.1533/9781780634432.45. |

| [2] | J. Andrew et al., «List of Contributors», in WTO Accession and Socio-Economic Development in China, P. K. Basu et Y. M. W. Y. Bandara, Éd., in Chandos Asian Studies Series. , Chandos Publishing, 2009, p. v-viii. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-84334-547-3.50015-1. |

| [3] | S. Lall, «Export performance technological upgrading and foreign direct investment strategies in the Asian newly industrializing economies. With special reference to Singapur», n° 88. |

| [4] | C. Terra, «2 - How to Measure International Transactions», in Principles of International Finance and Open Economy Macroeconomics, C. Terra, Éd., San Diego: Academic Press, 2015, p. 9‑30. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802297-9.00002-6. |

| [5] | A. Ouanes et S. M. Thakur, «CHAPTER 4 Balance of Payments Accounts and Analysis», in Macroeconomic Accounting and Analysis in Transition Economies, International Monetary Fund. Consulté le: 12 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781557756282/C04.xml. |

| [6] | «(PDF) Deconstructing the Theory of Comparative Advantage», ResearchGate. Consulté le: 12 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301477000_Deconstructing_the_Theory_of_ Comparative_Advantage. |

| [7] | I. M. Fund, «3. Balance of Payments Accounts», in Financial Programming and Policy the Case of Turkey (Reprint), International Monetary Fund. Consulté le: 12 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781557758750/ch006.xml. |

| [8] | E. Beretta et A. Cencini, «Double-entry bookkeeping and the balance of payments: the need for a substantial, conceptual reform». |

| [9] | S. A. Athari, F. Irani, et A. AlAl Hadood, «Country risk factors and banking sector stability: Do countries’ income and risk-level matter? Evidence from global study», Heliyon, vol. 9, n° 10, p. e20398, oct. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20398. |

| [10] | S. Khalil, A. Sirag, et H. Attia, «Implications of Capital Inflows on Financial Stability in Arab Countries». |

| [11] | vilis, «Lebanon’s Balance of Payments Sealed 2017 with a $155.7M Deficit», BLOMINVEST. Consulté le: 13 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://blog.blominvestbank.com/24657/lebanons-balance-payments-sealed-2017-155-7m-deficit/. |

| [12] | «Dollarization for Lebanon», Cato Institute. Consulté le: 13 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.cato.org/blog/dollarization-lebanon. |

| [13] | «Public Information Notice: IMF Concludes Article IV Consultation with Lebanon», IMF. Consulté le: 13 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/28/04/53/pn01109. |

| [14] | «Lebanon-Economic-Monitor-Lebanon-Sinking-to-the-Top-3.pdf». Consulté le: 13 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/394741622469174252/pdf/Lebanon-Economic- Monitor-Lebanon-Sinking-to-the-Top-3.pdf. |

| [15] | vilis, «Lebanon’s Balance of Payments Deficit Stood at $10.55B by December 2020», BLOMINVEST. Consulté le: 13 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://blog.blominvestbank.com/39429/lebanons-balance-of-payments-deficit-stood-at-10-55b -by-december-2020/. |

| [16] | T. Hitiris, «2. Tax Structure, Trade Taxes, and Economic Development: An Empirical Investigation», in Fiscal Policy in Open Developing Economies, International Monetary Fund. Consulté le: 13 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781557751713/ch003.xml. |

| [17] | A. Filardo et S. Grenville, «Central bank balance sheets and foreign exchange rate regimes: understanding the nexus in Asia». |

| [18] | M. D. Bordo, «The Bretton Woods International Monetary System: A Historical Overview», in A Retrospective on the Bretton Woods System: Lessons for International Monetary Reform, University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 3-108. Consulté le: 13 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/retrospective-bretton-woods-system-lessons-international -monetary-reform/bretton-woods-international-monetary-system-historical-overview. |

| [19] | J. T. Harvey, «Exchange rates and the balance of payments: Reconciling an inconsistency in Post Keynesian theory», Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, vol. 42, n° 3, p. 390-415, 2019, Consulté le: 13 janvier 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48540976. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML