-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2023; 13(2): 60-70

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20231302.03

Received: Apr. 17, 2023; Accepted: Apr. 25, 2023; Published: Apr. 28, 2023

Causality between Intra-African Trade Openness and Transport Infrastructure Development, Industrial Development, and Customs Duty Rate in African

Laïfoya Moïse Lawin1, Romaric Dossa2, Cassius Feliho3

1Statistician-Economist-Engineer, General Direction of Economy, Ministry of Economy and Finances, Cotonou, Benin

2Statistician-Economist, National School of Applied Economics and Management, University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin

3Engineer in Modelling and Numerical Simulation, National Higher School of Mathematics Genius and Modelization, National University of Sciences, Technologies, Engineering and Mathematics, Abomey, Benin

Correspondence to: Laïfoya Moïse Lawin, Statistician-Economist-Engineer, General Direction of Economy, Ministry of Economy and Finances, Cotonou, Benin.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The literature seems to focus on tariffs as the main factor limiting trade between African countries. This study highlights other factors that affect trade in Africa. It examines the causality between intra-African trade openness and the transport infrastructure development index, industrial development index, information and communication technologies (ICT) development, the business and competition regulation index, and the Customs duty rate. The panel causality test of Granger (1969) and Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) using to data from 36 African countries over the period 2010-2019. The results of the Granger causality test reveal that there is a causal relationship between internet access, mobile phone access, customs duty rate, transport infrastructure development, business and competition regulation and intra-African trade openness. There is a bidirectional causality between intra-African trade openness and the development of the industrial sector on the one hand, and a bidirectional causality between the development of transport infrastructure and the development of the industrial sector on the other. The results suggest African countries should put in place policies that focus on transport infrastructure development and industrial development. African governments should also strengthen the development of communication infrastructure (access to the Internet and mobile telephony) and intensify exemptions from customs duties on imports of equipment acquired in the context of industrial development and the construction of transport infrastructure.

Keywords: Intra-african trade opening, ZLECAF, Customs duty rate, Transport Network Development, Industrialization, TIC development, Competition Regulation

Cite this paper: Laïfoya Moïse Lawin, Romaric Dossa, Cassius Feliho, Causality between Intra-African Trade Openness and Transport Infrastructure Development, Industrial Development, and Customs Duty Rate in African, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 13 No. 2, 2023, pp. 60-70. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20231302.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- International trade is today one of the ways for the development of African countries. After the work of David Ricardo (1817), many authors have put the issue of international trade at the heart of the development of nations. The Heckscher-Ohlin theory supported the idea that factor endowments determine the comparative advantages of countries and the structure of world trade. For this school of thought, as a country becomes more capital-rich, production and exports become more capital intensive. Thus, a country that is relatively abundant in a factor of production tends to export goods that are high in that factor (Guarascio al. 2022). Aware of the crucial role of trade openness and the benefits to be gained from international trade, the majority of African countries have shown, since the 1980s, their willingness to develop a regional integration through the implementation of the Lagos Plan in 1980. African countries embarked on a wave of market integration with trade liberalisation as a corollary. In this process of globalisation from which no nation can escape, the main question is no longer whether to open up but rather how to open up, and what are the strengths and weaknesses of the economy in the international market. In response to these new demands, integrated economic blocs have been formed in several parts of the world. Thus, from the 1990s, in an effort to get back on track, several institutions were created in Africa, notably: the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU). The year 2001 was also decisive for the acceleration of the state of regional integration, through the creation of the African Union (AU) and the establishment of the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) (Allali, 2022). A partnership has also been signed between the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP) and the European Union (EU) through Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs). These institutions are set up to facilitate intra-African cooperation and trade in goods and services, and to reduce the punitive impacts (whether customs, legislative or physical) of borders (Reitel, 2018). Despite this willingness to open up, African countries' trade with the rest of the world and intra-African trade remains low. Indeed, trade between Africa and the rest of the world represents only 3% of world trade and only 16% of intra-African trade (UNCTAD, 2019; DOSSO et al., 2022), in contrast to trade between European countries, which represents nearly 68% of Europe's trade (UNCTAD, 2019). Several studies have attributed the low level of intra-African trade to the problems of: availability of economic infrastructure, adequacy of economic policies, existence of unrecorded trade flows and the quality of national sub-regional and regional institutions (Harrison et al. 2005; Agbodji, 2008; Longo et al., 2004; Limao et al., 2001).In 2012, under the aegis of the African Union, an initiative was launched to establish an African Continental Free Trade Area (Allali, 2022). The signatory countries of such an agreement agreed to: (i) eliminate tariffs on most goods; (ii) liberalise trade in key services; (iii) address non-tariff barriers to intra-regional trade; (iv) create a single continental market with free movement of labour and capital. Despite the willingness of African policy makers, most trade facilitation measures or instruments within economic or monetary areas in Africa have struggled to be implemented, due to the fact that a large share of African countries' national or fiscal revenues comes from taxes and tariffs on foreign trade. For example, taxes and customs duties on foreign trade vary between 38% and 56% of fiscal revenues in WAEMU countries, according to BCEAO data. Most African countries cover their budgetary expenditures from tax and customs revenues. In other countries, policies of imposing customs duties and import or export taxes are part of a protectionist policy to protect domestic industry and stimulate local consumption. They are also part of the policy of combating the fraudulent export of essential goods, with a view to combating food insecurity. In addition to the above, most African countries do not have the necessary transport infrastructure to facilitate the smooth flow of goods and services. In addition, some countries have not yet reached a level of industrialisation that would allow them to benefit from comparative advantages; since trade openness is determined by the level of productivity of countries, their technological advancement and their relative endowment in factors of production (Ricardo, 1817; Heckscher and Ohlin 1933).The literature on the issue of the impacts of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) on the economies of African countries has mostly focused on assessing the effects of tariff reduction on African economies, as well as the effects of trade facilitation measures on African welfare. Previous work uses descriptive analysis or simulation techniques such as computable general equilibrium modelling (Chauvin et al. 2016, Vanzetti et al. 2018) and the Global Trade Analysis Project technique (Vanzetti et al., 2018) to examine the effect of a tariff cut on macroeconomic aggregates. These techniques are sometimes based on strong assumptions that do not take into account the time dynamics and interdependence between countries, which is a limitation of the literature. These findings give the impression that non-tariff barriers such as the availability and quality of transport infrastructure (road and rail), anti-competitive rules, the level of industrial development and the issue of insecurity in some African countries do not constitute a barrier to the development of intra-African trade. Thus, this study raises the following questions: is there a causal relationship between Customs duty rate and intra-African trade? Is there a causal relationship between non-tariff barriers (transport infrastructure, ICT development, national anti-competitive provisions, and level of industrial development) and intra-African trade? This study attempts to answer these questions by examining the causal link between Customs duty rate, non-tariff barriers and intra-African trade. Through this study, we aim to contribute to the existing literature on the relationship between intra-African trade and non-tariff barriers (transport infrastructure, ICT development, national anti-competitive provisions, level of industrial development). This paper is structured in six (6) sections. The first section presents the concept of the study as well as the state of play of trade agreements between African countries. This section is followed by the literature review, the methodology, the results, the discussion, and the conclusion and recommendations.

2. Literature Review

- International trade theoryRecent research has shown that free trade is not always beneficial to all economies. Only well industrialised economies with competitive firms benefit from free trade. Baccini et al. (2017) have shown that preferential trade agreements (PTAs) favour only the most internationally competitive firms. Indeed, lower international tariffs only improve the profitability of the largest and most productive firms in foreign services. For Baccini et al. (2017), preferential liberalisation increases the political influence and lobbying capacity of the most competitive firms, and further widens the gap with smaller firms that are forced out of the market. Similarly, De Rogatis (2022) has shown that in a labour-rich but capital-poor economy, protectionism would benefit capital and harm labour; and trade liberalisation would benefit labour and harm capital. In such an economy, workers benefit from increased trade relations when the country is overpopulated with labour, because they own mainly the labour factor. Protectionism, on the other hand, harms and deteriorates their political status and economic wealth. However, the reality of some countries challenges Heckscher-Ohlin's theory. The case of China over the period 1999-2007 is a perfect illustration of this contradiction. Indeed, China was clearly more capital-rich in 2007 than in 1999 (Huang et al., 2015). According to the Heckscher-Ohlin theory, China should produce and export more capital-intensive goods, but the changes in export patterns observed over this period seem to contradict the Heckscher-Ohlin theory (Huang et al., 2015), due to the technological changes that China experienced over the period.African Continental Free Trade AreaThe literature on the question of the quantitative impacts of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) has mainly focused on assessing the welfare effects of tariff reduction and trade facilitation measures on Africans. Computable general equilibrium (CGE) modelling and the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) technique are the most widely used in studies to assess the impacts of tariff reduction shocks. Vanzetti et al. (2018) measured the impacts of the African Continental Free Trade Area considering three scenarios: (1) full tariff elimination; (2) tariff elimination with exemptions for 5 per cent of sensitive products; and (3) reduction of tariffs and non-tariff barriers without tariff reductions. The results of these studies reveal that by eliminating all applied tariffs, the African continent would experience an annual increase in trade of up to US$3.6 billion. Demand for labour, both skilled and unskilled, will rise sharply, particularly in countries such as Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. However, the results are asymmetrical across the continent, with Angola, Nigeria and South Africa being the main winners. In some countries, there may even be a reduction in welfare in the medium to long term - for example, in Burkina Faso, Malawi, Mozambique and Rwanda when agricultural tariffs are eliminated (Chauvin et al. 2016). The work of Abrego et al. (2019) shows how the African continent can benefit most from tariff cuts. The welfare increase in this scenario is 2.1 per cent compared to the baseline scenario, with all countries benefiting from an increase in welfare, and nine of them recording gains of 5 per cent or more. Vanzetti et al (2018) shows that the costs associated with sanitary and phytosanitary measures and technical barriers to trade can be reduced by 25%, and traditional barriers, such as quotas, can be completely eliminated without any country suffering losses. Kassa et al. (2019) found that most of the export gains came from oil and other mineral exports, while other countries recorded gains in manufacturing and others in industrial goods. Trade determinants Several works highlight the explanatory factors of trade openness, imports and exports. Analyses by Mikulić et al. (2018) show that imports are related to final demand, household spending, GDP and the level of investment. The work of Riker (2020) reveals that trade is determined by the level of regional expenditure, international trade costs, regional price indices and the price of domestic products. Emran et al. (2010) estimate the import demand function in developing countries. They establish a link between total imports, import price index/consumer price index. The results of their work reveal the existence of a positive and significant effect of per capita income on imports. To shed light on the determinants of Chinese imports, Zhang et al. (2013) introduce in a multilevel approach variables deflated by Chinese imports, average tariffs of a group of products, the price index, the exchange rate of the Ren Min Bi against the US dollar, GDP or one of the final expenditure categories (private consumption, government expenditure, investment and export). The analysis reveals that private consumption expenditure has more influence than the other expenditure categories. In addition, the exchange rate, customs duties and the domestic price index have an impact on import demand.Yazici (2012) estimates the import and export demand functions for Turkish agriculture using the boundary test approach to cointegration modelling and error correction. It estimates imports from real GDP, import prices, domestic goods prices, and the effective exchange rate. Exports are estimated from real world income, the domestic price of exports, the price of world exports, and the exchange rate. The results show that the relative price is a significant determinant of imports in both the short and long run, while the exchange rate is only important in the long run. Yue et al. (2010) examine the effect of final consumption expenditure, investment expenditure, export expenditure and relative prices on import demand. The estimation results conclude that investment and exports are the main determinants of Côte d'Ivoire's imports in the long run, while in the short run final consumption expenditure and investment expenditure are the main determinants of imports. He also points out that Côte d'Ivoire's import demand is not sensitive to price changes. The results of the studies by Matlasedi (2017) showed that the exchange rate, domestic GDP, relative prices and foreign reserves positively influence merchandise imports in the short run. Ngoma (2020) analysis of the determinants of Zimbabwe's imports shows that the gross domestic product of the importing and exporting country, the geographical distance between the country (represented by the distance in kilometres between the capitals of the importer and exporter), the level of inflation for the importing and exporting country (represented by the CPI), the population levels for each of the countries and a dummy variable for a regional trade agreement affect Zimbabwe's imports. Hussain et al. (2020) examine the determinants of export supply in Pakistan. Using an ARDL model, these authors measure the effects of relative price (the ratio of export price to domestic prices), production cost (represented by the producer price index), production capacity and domestic demand pressure on exports. The results find that relative prices as well as cost of production have a greater impact on the export performance of raw materials and value-added manufactures. Furthermore, the analysis shows that production capacity and domestic demand pressure influence the export supply. Several other factors have been identified in the literature as influencing trade. These include tariffs, protectionist policies, ICT development, transport infrastructure development, insecurity and the level of industrial development. For Azhimetov (2014), customs duties perform several functions. They are a non-tax revenue of the budget system and a tool for customs regulation of foreign trade activity. Indeed, tariffs and other forms of trade regulation generate significant revenue for the government (Elbadawi, 2008). Tariff policies also limit bilateral trade exchange (Karim et al., 2022). Yeo et al. (2019) examine the impacts of trade policy measures on trade flows between Pakistan and its major trading partners for the period 2006-2015. The results reveal a significant correlation of trade policy variables on exports and imports. They find a negative effect of tariff barriers on trade of developing countries. They indicate that trade policy specifics have a statistically significant effect on exports and imports. In the same perspective, Campi et al. (2019) analysed the effect of trade agreements on bilateral trade flows. Levitt et al. (2018) examined the impact of China's trade liberalisation on greenhouse gas emissions of WTO member countries. Overall, these authors concluded that the proliferation of free trade agreements can have a positive impact on international trade. Other work has assessed the importance of technological development on trade. Nath et al. (2012) examine the effects of information and communication technologies (ICT) on international trade in emerging markets. The results indicate that internet subscriptions and internet hosts have a significant positive impact on export and import. Ozcan (2018) analyses the impacts of ICT on international trade between Turkey and its trading partners. He finds that ICT has a positive and significant impact on Turkey's import and export volumes. However, the effect of ICT is more significant on imports than on exports. Nath et al. (2017) examined the impacts of ICT development on exports, imports and total trade of ten services from 49 countries over the period 2000 and 2013. The results indicate that ICT development has significant positive effects on financial services, insurance services, other business services, royalties and licence fees, transport and travel. The literature reveals the importance of security in the development of international trade. Analysis by Wulansaria et al. (2020) indicates that social factors such as feelings of trust and security play an important role in trade openness. However, the literature states that the effects of armed conflict on trade are mixed. Martin et al. (2008) found that bilateral military conflict has a significant negative impact on bilateral trade. This effect remains negative and significant for at least 10 years. Four years earlier, Bayer et al. (2004) showed that civil war reduces international trade. For these authors, it is possible that national armed conflicts hurt trade-dependent sectors more than other sectors. Wulansaria et al. (2020) found that crime has a significant negative impact on trade openness. In contrast, in their work Blomberg et al. (2006) find no statistical significance in the negative effect of military conflicts on bilateral trade. There is also an emerging consensus that trade between states reduces the risk of militarised conflict between them (Elbadawi et al., 2008). However, the analysis of Martin et al. (2008) shows that the idea that trade promotes peace is only partially true. They show that countries that are more open to global trade have a higher probability of war because multilateral trade openness reduces bilateral dependence on a given country and the cost of bilateral conflict. In the next section, we present the methodology used to examine the different causal links.

3. Data and Methods

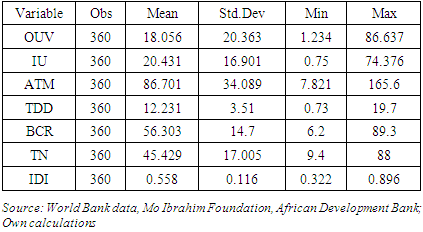

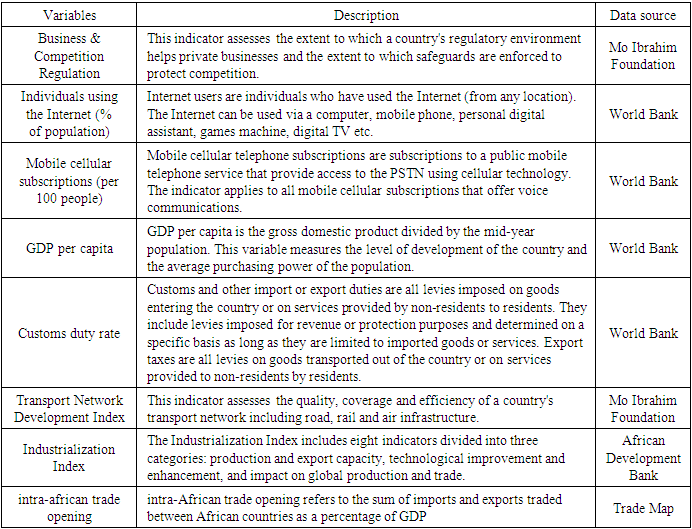

- Data and Source Analyses In this study are made on a panel of 36 African countries: South Africa; Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Congo, Democratic Republic, Ivory Coast, Egypt, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mali, Morocco, Mauritius, Mauritania, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Uganda, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Zimbabwe. The countries are selected according to data availability. The data used are from the World Bank, African Development Bank, Mo Ibrahim Foundation and Trade Map databases, and cover the period 2010 to 2019. It should be noted that although these are two-thirds of the countries in Africa, the 36 countries weigh in the African economy. Indeed, statistics show that over the period under review, the 36 countries account for about 83% of Africa's population, between 87% and 91% of African GDP, and between 86% and 93% of intra-African trade.The variables used are: Business & Competition Regulation (BCR), Individuals using the Internet (% of population) (IU), Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people) (ATM), Customs duty rate (TDD), Transport Network Development Index (TN), Industrialization Index (IDI), and intra-African trade opening (OUV). Trade openness is defined as the sum of imports and exports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP. In this study, intra-African trade opening refers to the sum of imports and exports of goods and services traded between African countries themselves, as a percentage of GDP. The table (annex A) in the appendix describes the different variables used and the source of the data.Descriptive Statistics The analysis of Table 1 shows that the average degree of intra-African trade openness for the 36 countries is 18.05% over the 2010-2019 period, with a minimum level of 1.23% and a maximum level of 86.6%. The average tariff rate varies between 0.73% and 19.7%, with a standard deviation of 3.5% and an average of 12.2%. The statistics indicate that the industrial development index varies between 0.322 and 0.896 for the 36 countries studied. The average of this index is 0.558, with a standard deviation of 0.116. Furthermore, the index of development of transport networks or infrastructure is on average 45.4%, with a standard deviation of 17.0%. The index measuring the degree of business protection averages 56.3% over the underlying period.

|

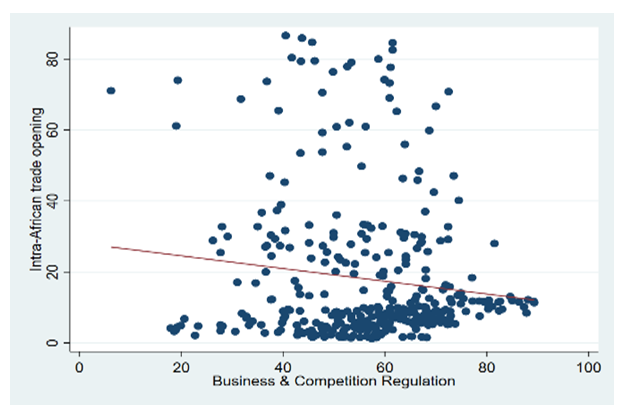

| Figure 1. Intra-African trade openness and Business & Competition Regulation. Source: Trade Map, Mo Ibrahim Foundation, author’s calculations |

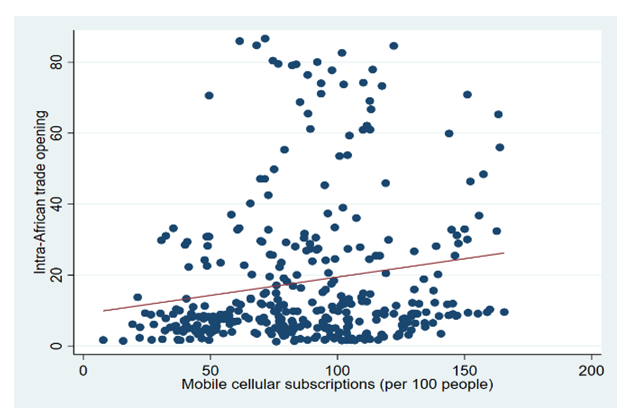

| Figure 2. Intra-African trade openness and Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people). Source: Trade Map, World Bank, author’s calculations |

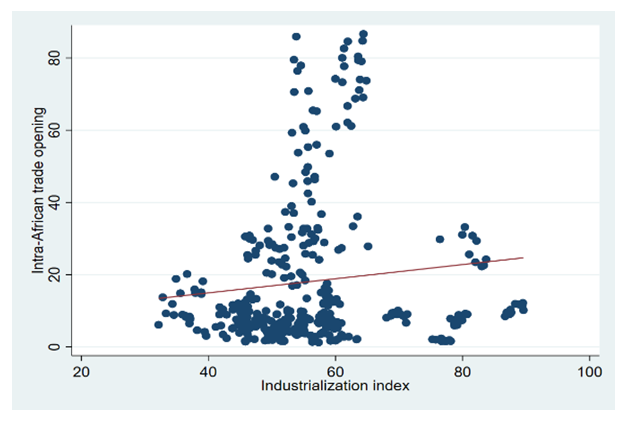

| Figure 3. Intra-African trade openness and Industrialization Index. Source: Trade Map, African Development Bank, author’s calculations |

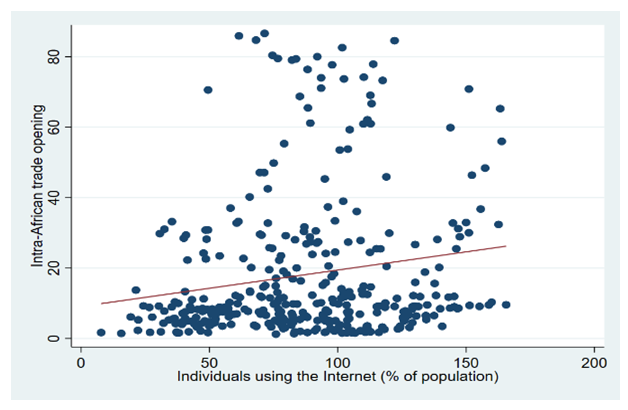

| Figure 4. Intra-African trade openness and Individuals using the Internet (% of population). Source: Trade Map, World Bank, author’s calculations |

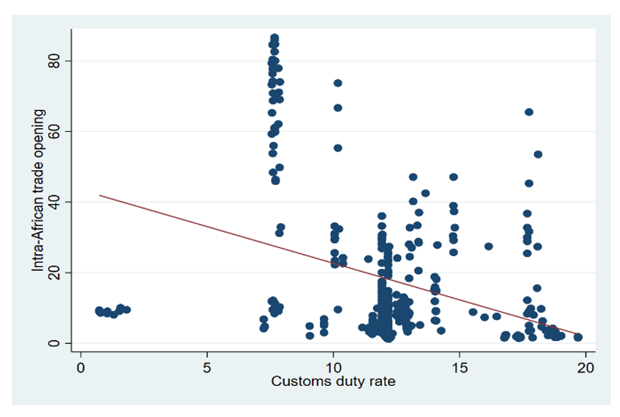

| Figure 5. Intra-African trade openness and Customs duty rate. Source: Trade Map, World Bank, author’s calculations |

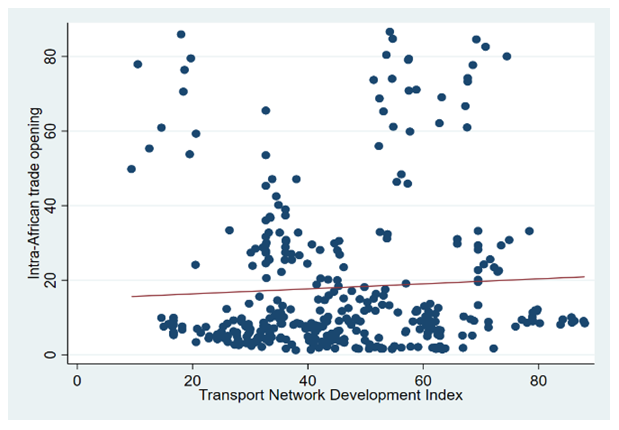

| Figure 6. Intra-African trade openness and Transport Network Development Index. Source: Trade Map, Mo Ibrahim Foundation, author’s calculations |

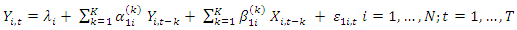

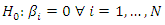

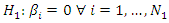

Under the null hypothesis of homogeneous non-causality, there is no causality from X to Y for all cross-sectional units in the panel.

Under the null hypothesis of homogeneous non-causality, there is no causality from X to Y for all cross-sectional units in the panel.  The alternative hypothesis assumes the existence of causality from X to Y for at least one country.

The alternative hypothesis assumes the existence of causality from X to Y for at least one country.

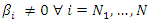

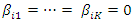

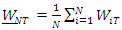

The null and alternative hypothesis of causality from y to x is specified in the same way. To test these hypotheses, Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) propose a procedure that consists of running the N individual regressions of the model and performing F-tests of the K linear hypotheses

The null and alternative hypothesis of causality from y to x is specified in the same way. To test these hypotheses, Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) propose a procedure that consists of running the N individual regressions of the model and performing F-tests of the K linear hypotheses  to recover the individual Wald statistic

to recover the individual Wald statistic  and finally to calculate the average Wald statistic

and finally to calculate the average Wald statistic

Where

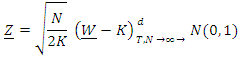

Where  are the individual Wald statistics for the Granger causality test. Assuming that the statistics are independent and identically distributed, we calculate a standardised statistic, Z-bar

are the individual Wald statistics for the Granger causality test. Assuming that the statistics are independent and identically distributed, we calculate a standardised statistic, Z-bar  are independent and identically distributed, we calculate a standardised statistic, Z-bar:

are independent and identically distributed, we calculate a standardised statistic, Z-bar:

4. Results

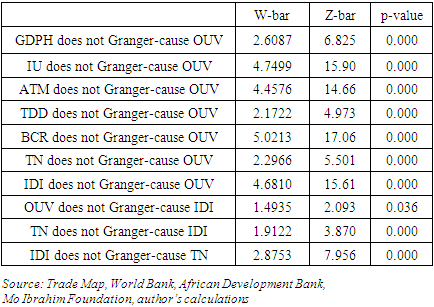

- The results reveal the existence of a causal link from ICT development (internet and mobile phone access) to intra-African trade openness on the one hand, and a bidirectional causality between industrial sector development and intra-African trade openness on the other. This means that ICT development and industrial sector development improve intra-African trade openness. Conversely, intra-African trade openness improves industrial sector development in Africa. Furthermore, the probability associated with the indicator statistic measuring the availability and quality of transport infrastructure (including road and rail) is P-value = 0.0000, under the null hypothesis, indicating that the degree of openness among African countries is determined in part by the development of transport infrastructure. It is worth noting that the statistics established a causal link between tariffs and intra-African trade openness. Furthermore, the results show a bidirectional causality between transport infrastructure development and industrial sector development, which means that industrial sector development in Africa cannot take place without transport infrastructure development.

|

5. Discussion

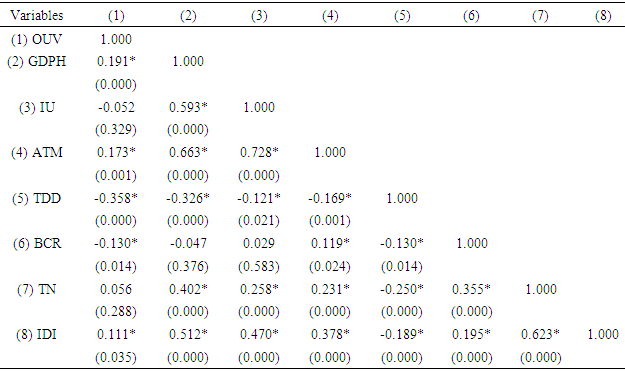

- This study finds a statistically significant relationship between intra-African trade openness and the import/export tariff rate. The estimates showed, on the one hand, a negative and significant correlation (r=-0.358 and p-value = 0.000) between the tariff rate and intra-African trade openness and a causality from the tariff rate to intra-African trade openness, on the other hand. This result corroborates the work of Roeger et al. (2022), Evenett et al. (2021), and Yeo et al. (2019) who establish a negative effect of tariffs on trade in developing countries. Roeger et al. (2022) justify their results by the fact that an increase in tariffs induces a slowdown in trade in goods. They point out that only large countries may find it advantageous to impose tariffs on their trading partners in order to increase national welfare, in line with optimal tariff theory which suggests that a large economy can increase national welfare by imposing a tariff unilaterally, due to a terms of trade gain. However, Roeger et al. (2022) concluded that not imposing tariffs on imports by multinationals reduces the negative effects on growth and real wages, since in this case there is a tariff jump effect. Developing countries prefer to protect themselves against increasingly unfair international competition by imposing taxes on international firms, thereby encouraging domestic production (Yeo et al., 2019). Our results show a negative and significant correlation between intra-African trade openness and the indicator measuring the degree of enforcement of measures to protect local firms from competition (protectionism), and also a causal relationship between the two variables. Such a result can be explained by the fact that protection measures weaken imports in favour of local products. All other things being equal, the application of protection measures in country X induces reciprocity measures on the part of its partners, which limit country X's exports to these partners and ultimately limit its exports and imports. Laws and protective measures are sometimes reinforced by strict environmental policies which have a substantial impact on foreign trade and therefore reduce trade flows.The results provide evidence of a causal relationship from ICT development (internet access, mobile phone access) to intra-African openness, a result that supports the existing literature that broadly shows that, e-commerce has the potential to increase trade openness and economic growth. The literature highlights the existence of several mechanisms through which ICT can affect the flow of international trade (Ozcan, 2018). Indeed, analyses by Wulansaria et al. (2020) reveal that ICT can reduce economic barriers between countries, thereby increasing foreign trade and openness to trade. Advances in ICT have also made physical distance unnecessary as a barrier to trade. The proximity requirement for face-to-face interaction between trading partners is no longer a necessary condition as ICT innovations such as telephone, email and virtual conferences have become substitutes for face-to-face interactions (Ozcan, 2018). In terms of communication costs, telecommunications help to maintain fast and efficient communication with business partners to support business competitiveness (Bankole et al. 2015, Ozcan, 2018). Also, by using ICT, firms are able to exchange information online from anywhere in the world, communicate just-in-time with customers and suppliers and deliver services as quickly and efficiently as possible (Nath et al., 2017). These mechanisms make markets more competitive and efficient by improving information flows and reducing transaction costs, such as fixed market entry costs, communication and information costs, and negotiation and coordination costs associated with trade (Ozcan, 2018).The availability and quality of transport infrastructure is a bottleneck for African trade. Analysis shows that the level of transport infrastructure development and the level of industrial development significantly influence intra-African trade openness. Similar conclusions are provided by the work of Kenderdine et al. (2021), Uysal (2019), and Gallego et al. (2018). These different authors have indeed shown that transport infrastructures open up a great opportunity for trade. Tabi et al. (2011), and Li et al. (2021) have also shown that industrial development induces an increase in international trade through technological innovations and the increase in the supply of goods and services for which there are demands in partner countries.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study examines the existence of a causal relationship between intra-African trade openness and tariffs, internet access, mobile phone access, industrial sector development, transport infrastructure development and the degree of protectionism. We apply Granger's (1969) panel causality test to data from 36 African countries over the period 2010-2019.The analyses show that African countries with a higher access to mobile phones and the internet tend to increase the degree of intra-African trade openness. Similarly, the more industrialised a country is, the higher its degree of intra-African openness; the more a country develops transport networks, the more it tends to improve its intra-African trade openness. On the other hand, a high tariff rate and a high degree of protectionism tend to lower the degree of intra-African trade openness. The statistics found a positive and significant correlation between intra-African trade openness and the industrial development index, access to mobile telephony and the absence of armed conflict. A significant negative correlation is established between the degree of intra-African trade openness and the indicators measuring the degree of protectionism and the Customs duty rate. Furthermore, the results of the Granger causality test show the existence of a causal relationship from variables (access to the internet, access to mobile telephony, development of the industrial sector, development of transport infrastructures; customs duty, degree of protectionism) to intra-African trade openness. Furthermore, a bidirectional causality is established between intra-African trade openness and industrial sector development on the one hand, and a bidirectional causality between transport infrastructure development and industrial sector development on the other.In view of the above, some recommendations are worth making. African countries should put in place policies that focus on the development of transport infrastructure (rail, road) and industrial development. Industrialisation in Africa can be done gradually and can be done in four main stages: (i) focus on light industry which requires low technology, (ii) develop heavy industry (textile and chemical industry), (iii) develop equipment sectors such as electrical equipment manufacturing and industrial plants, (iv) mobilise resources towards the sector that produces durable consumer goods African governments also need to strengthen the development of communication infrastructure (internet and mobile phone access) and invest more in the fight against insecurity. Governments have a choice as to whether to impose or waive tariffs. They can intensify duty exemptions on imports of equipment acquired in the context of industrial development and the construction of transport infrastructure.

Conflict of Interest Statement

- The author states that there is no conflict of interest. All statements or arguments made in this paper are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Ethical Approval

- The data used for the estimates do not include confidential information about individuals or animals that may raise ethical concerns.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank all those who have contributed to the improvement of the quality of this paper. Special thanks to all reviewers.

Consent for Publication

- The authors grant his consent for publication of this paper.

Funding

- The writing of this paper has not been funded or sponsored. It was done at the author’s expense.

Data Availability Statement

- The data used in this paper is fully available and can be accessed upon request.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML