-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2023; 13(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20231301.01

Received: Jan. 24, 2023; Accepted: Feb. 6, 2023; Published: Feb. 14, 2023

ICTs Development and Tax Revenue Mobilization in West African Economic and Monetary Union Countries

Laïfoya Moïse Lawin

Statistician-Economist-Engineer, Direction Générale de l’Economie, Ministère de l’Economie et des Finances, Cotonou, Benin

Correspondence to: Laïfoya Moïse Lawin, Statistician-Economist-Engineer, Direction Générale de l’Economie, Ministère de l’Economie et des Finances, Cotonou, Benin.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Mobilization of adequate tax revenues remains a key objective for African countries in the implementation of development policies. The objective of this study is to examine the effect of internet access and cell phone access on tax revenues in West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) countries, from 2000 to 2019. The data used are from the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) and World Bank database. The methodology used is based on the Granger causality test procedure and the fixed effect panel model. The results show that there is a causal relationship between cell phone access, internet access and tax revenues. The results of the estimates show that internet access and cell phone access have positive and significant effects on tax revenues, and a 10% increase in internet access increases tax revenues by 1.23%, and a 10% increase in mobile phone access increases tax revenues by 1.11%. The recommendations are that WAEMU countries should invest more in the digitalization of the economy and the tax system, improve access to good quality internet and cell phone access, and promote the use of digital technology in resource mobilization processes.

Keywords: Information and Communication Technology (ICT), Internet users, Cell phone access, Tax revenues, WAEMU countries

Cite this paper: Laïfoya Moïse Lawin, ICTs Development and Tax Revenue Mobilization in West African Economic and Monetary Union Countries, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2023, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20231301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Since the early 1960s, domestic resource mobilization has been considered a key factor in the economic development of African countries. In the post-independence era, the need for greater autonomy in financing development placed the issue of taxation at the heart of development objectives (Hammed, 2020). Tax resources are essential to ensure government spending and the financing of infrastructure on which economic development and growth are based, on the one hand, and the environment in which business activities are conducted, on the other. Similarly, social security, infrastructure and basic services such as education and health care are provided in part by the tax resources collected by the state. The literature shows that some authors perceive taxation as a disincentive to innovation or investment. This idea is supported by neo-classical theories of investment models (Hayashi, 1982), which postulate that taxation is harmful to the development of firms because it tends to modify their investment decisions (Hall et al., 1967; Summers et al., 1981). Mirrless (1971), Laffer (1981), Saez (2016), and Aghion et al. (2017) support the thesis that the effect of taxation on firm performance is twofold. Laffer (1981) believes that there is a threshold in the tax rate beyond which tax policy becomes harmful to the economy. This threshold depends on the level of development from one country to another and on the tax and incentive policies implemented.For better convergence of economies, economic or monetary areas set themselves principles or convergence criteria, including the tax threshold or tax burden. Thus, over the last three decades, the countries of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) areas have set a minimum tax burden of 17% of GDP, which has been revised to 20% of GDP since 2015. However, the current situation of African countries and the WAEMU, in terms of tax revenue mobilization, makes it easy to understand that revenue mobilization policies lack effectiveness. Despite the reforms implemented in recent years in some WAEMU countries, namely the reform on the introduction of electronic VAT invoicing machines, the reform on the payment of taxes by bank transfer, the reform on the online declaration and payment of taxes, and the reform giving the possibility of filing financial statements online via the e-balance sheet platform, the tax potential is still enormous in most countries of the Union. Works of the World Bank (2018), the World Bank (2019) and the International Monetary Fund (2018) in the case of African countries and the one carried out by Lawin (2020) on the specific case of Benin testify to a significant fiscal potential, as a result of under mobilization of tax revenues. At continental level, tax policies also lack efficiency in their implementation. One proof is that in its 2017 publication on government revenue in Africa, the OECD indicates that the tax collection rate (defined as total tax revenue, including social contributions, expressed as a percentage of GDP) in Africa is on average in the range of 18% to 21%. This low level of tax revenue collection in Africa is partly justified by the preponderance of the informal sector, institutional problems, a low level of ICT development and a low level of use of ICT in the resource mobilization process.In the last decade, a few studies have highlighted the important role that ICT plays in development and in the collection of government resources. However, the existing literature on the issue of the relationship between ICT development and tax revenue mobilization in the case of African countries has focused on broad geographical areas. For example, the work of Ofori et al. (2022) was conducted on 42 African countries and that of Adegboye et al. (2022) was conducted on 48 sub-Saharan African countries. These studies did not take into account the influence of membership in a currency area or membership in agreements on common external tariffs in the choice of countries. The fact that countries have common objectives (convergence criteria) in terms of tax revenue mobilization may influence their efficiency in collecting resources compared to countries that do not belong to the same area. The adoption of common external tariffs influences the VATs at the customs, import duties and export duties of countries adhering to the common external tariff treaty. Similarly, the fact that some countries are under fixed exchange rate regimes or have a common currency influences the revenues on foreign trade compared to countries that are under flexible exchange rate regimes (Adam et al., 2001; Kwesi et al., 2018). The literature provides little information on the extent to which ICT can realize its full potential to improve tax revenue mobilization in WAEMU countries that are under a fixed exchange rate regime with common external tariffs, and whose total tax revenue is still well below 20% of GDP, the minimum recommended by the union's member states.Thus, this study addresses the above gaps in the literature by investigating the effect of Internet and cell phone penetration on tax revenues in WAEMU countries. Specifically, the research questions we seek to answer in this study are : (i) is there a causal relationship between internet penetration, cell phone penetration and tax revenues in WAEMU countries? (ii) what are the real effects of internet and cell phone penetration on tax revenues in WAEMU countries? These are the questions we seek to answer in this study, using the Granger causality test and the fixed-effect panel model. To accomplish this, we have organized the paper into five sections. After the introduction, we are going to present the literature review, followed by the methodology, the presentation of results and discussion. We conclude with a conclusion and policy recommendation.

2. Literature Review

- The literature on the issue of state resource mobilisation is based on Adams Smith (1869) taxation principles and the benefit theory developed by Wicksell (1896) and Lindahl (1919). According to Adams Smith's theory of taxation, the tax system must strike a balance between the interests of the taxpayer and the tax administration. He based his argument on four principles, known as the canons of taxation (the canon of equity, the canon of certainty, the canon of convenience and the canon of economy) (Nyaga et al., 2016). According to the principle of equality as defined by Smith (1869), each person should pay to the government according to his or her ability to pay that is, in proportion to his or her income or revenue. He supports the principle that taxes should be proportional to income. Smith (1869) is canon of certainty is based on the arguments that "the tax which each individual is required to pay must be certain and not arbitrary". For the author, the time of payment, the method of payment, the amount to be paid must be clear and unambiguous to the taxpayer and to any other person (Nyaga et al., 2016). This highlights the issue of transparency in the payment of taxes. With regard to the third principle, Smith (1869) emphasised the canon of convenience. Indeed, beyond certainty, Smith (1869) believes that the timing and method of payment must also be convenient for the taxpayer. The Canon of Economy refers to the costs and benefits of collecting a tax. For Smith (1869), if the costs of collecting a tax are greater than the total revenue it generates, there is no point in levying it.Wicksell (1896) and Lindahl (1919) developed the benefit theory which is based on the principle that the state should levy taxes on individuals according to the benefits they receive. This means that more benefits a person derives from the activities of the state, the more he should pay to the state. Such a theory aims to ensure that each individual’s tax obligations are based as much as possible on the benefits he or she receives from public services.Several decades after the development of these theories, issues related to taxpayers’ tax obligations as well as transparency in state revenue mobilisation and equality in taxation remain. Many analysts have found that ICTs are effective tools to easily communicate with taxpayers about their obligations and to better address issues related to transparency in the management of state resources. Although there is very little literature on the theoretical link between ICT and tax revenue, most work has highlighted the facilitating role that ICT plays today for socio-economic development.In current era, no sector of activity is spared from the effects of information and communication technologies. Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have introduced over the past two decades a range of new services for individuals, businesses, and governments in terms of modern technological advancement, economic growth, improved social welfare services, and even the way politics is conducted (Cruz-Jesus et al., 2016; Chohan et al., 2022). They have great potential to participate in the structural transformation of the African economy. Their roles and benefits for socio-economic development have been highlighted by a large number of researchers including Alzahrani et al. (2018), Khasawneh et al. (2013), Samoilenko et al. (2018), Weerakkody et al. (2016), Canares (2016), Ziemba (2019), Mahmood et al. (2019), and Kouton et al. (2020). The works have shown that the benefits of ICT extend to both the private and public sectors. Indeed, through their work, these authors have provided evidence that shows that the benefits offered by ICTs include improved transparency, improved participatory democracy, reduced government spending and reaching a wider population, instant access to information, improved health outcomes, and reduced mortality of children under five years. The effects of ICT on economic growth have been highlighted in the work of Haldar et al. (2022), Solomon et al. (2020), and Salahuddin et al. (2016). The results of the works of these authors have revealed, in the last two decades, a significant increase in global economic growth, thanks to the general use of technology in a large number of economic activities. While these authors have found positive effects of ICT development on economic growth, the work of Ogbo et al. (2021) has shown that the effect of ICT on productivity and growth is not necessarily significant because the implementation of ICT requires significant skills development before its full potential can be realized. Access to technology represents for the private sector a key factor in successful service delivery and this can be achieved by introducing and developing various distribution channels in developing countries (Joshi et al., 2018). The effects of ICT in this sector occur at two levels. The first is in the production phase, where the use of ICT contributes to a reduction in the cost of production, thus lowering the cost of products in the market. They thus contribute to increasing economies of scale in production. Through the multiple use of information, applications and software, and the flexibility of the production system, ICTs allow companies to access larger markets, increase their size and boost their profits (Mattes et al., 2012), and in fine to increase their contributions to the State’s revenues. The second level concerns the use of ICT in the marketing of products and services (Yushkova, 2014). The crucial role of ICT development in the development of trade has been highlighted by (Yushkova, 2014). The results of Yushkova, (2014) showed that a 1% increase in Internet use increases total exports by about 27% in WAEMU countries. The public sector has not been left behind by the advent of information and communication technologies. Canares (2016) show that ICTs offer two opportunities for government. For the author, ICTs allow to improve the productivity of factors, and the efficiency and effectiveness in the government services. The ICTs also provide better quality services to citizens. Several studies have also highlighted the role of new information and communication technologies in the mobilization of government resources. Mallick (2021) indicates that theoretical contributions on the link between reliance on modern ICT infrastructure and the extent to which this infrastructure induces greater tax compliance and contributes to higher tax revenues are certainly lacking. However, several works have established empirical links between ICT and state resource mobilization. The results of Canares (2016) obtained in a study of 15 municipalities in a Philippine province, shed light on the impact of ICT on local revenue generation. His study examines the impact of e-taxation policy on resource mobilization for provincial development. His findings reveal that the use of ICT can enable more transparent revenue generation systems for the benefit of government and taxpayers. He highlighted the influence of ICT in simplifying tax management, making the tax system more cost-effective, making tax assessment and service delivery more efficient, and processing local tax records and documentation more quickly. In the same vein, Girard (2015) came to the conclusion that access to cell phones and an internet connection allow citizens to enjoy government services efficiently. Using data from 42 African countries over the period 1996 – 2020, Ofori et al. (2022) show that only ICT use and skills form significant synergies with industrialization on resource mobilization efforts. They also show that ICT diffusion, ICT access, ICT use and ICT skills are key instruments to amplify the effect of industrialization on tax revenue mobilization efforts. Based on the literature, we have identified several channels or mechanisms through which ICT can affect tax revenue mobilization.Previous analyses show that ICTs stimulate growth and development through capital-enhancing techniques, accelerating productivity, and enabling innovation in ICT-enabled sectors. The work of Ofori et al. (2022) indicates that ICTs offer real opportunities to widen the tax net, combat tax evasion and corruption in the tax system, and reduce the cost of tax collection. Ofori et al. (2022) and McCluskey et al. (2019) argue that the effects of ICT on tax revenue are through accelerating the formalization of informal sector businesses into the tax net, reducing the marginal cost of collecting a unit of tax, and reducing the cost of compliance in countries with high levels of informal activity. Analysis of Houssa et al. (2017) indicate that ICT penetration can contribute directly to increasing tax revenues through increased compliance, reduced collection and control costs, and indirectly through improved efficiency in resource allocation. The use of ICT also leads to improved administrative efficiency, effectiveness and productivity in service delivery, and reduced administrative, operational and transaction costs for the public. Mallick’s (2021) analyses reveal that revenue enhancement through ICT is achieved through formal e-commerce, the use of electronic money, and the reduction of black money transactions. For example, Hondroyiannis et al. (2017) show in the case of Greece that the imposition of a restriction on cash withdrawals in July 2015 triggered a surge in magnetic card payments by consumers, and led to an unprecedented surge in tax revenue collection, thanks to a good quality internet connection. For Bruno (2019), ICT can boost tax revenue growth through the dissemination of information on tax collection enforcement, tax compliance, and tax morale. At the empirical level, several authors have found a positive effect of ICT on tax revenues. Ofori et al. (2022) examined the joint effects of industrialization and ICT diffusion on resource mobilization in a panel of 42 African countries. Over the period 1996 - 2020, the authors find that industrialization and ICT diffusion improve the tax on goods and services, corporate and income tax mobilization efforts. In a similar study, Adegboye et al. (2022) examined the influence of ICT on government revenue mobilization in a panel of 48 Sub-Saharan African countries over the period 2004-2020. The results of the work reveal that the net impacts of ICT on revenue mobilization are substantially positive, but the corresponding marginal effects of the ICT indicators (telephone penetration rate, cell phone penetration rate and Internet penetration rate) are extremely negative. They also establish the existence of threshold effects of cell phone and Internet penetration rates at which the effect of ICT on total income from taxes or income from income taxes varies. In contrast, other work has shown the negative effect of ICT on national revenues. The results of Mallick (2021) surprisingly reveal that ICT infrastructure and governance quality do not have a significant positive effect on overall tax revenue collection in some states in India. A large literature has also been devoted to examining the determinants or explanatory factors of tax revenue mobilization. Through a random-effects panel data study, Tounsi et al. (2019) showed that economic growth, net foreign assets (as a % of GDP), the consumer price index, population growth, the old-age dependency ratio, the budget balance and public debt (as a % of GDP) explain the level of tax pressure. Doghmi (2020) estimates fiscal capacity for a panel of 76 developing countries over the period 1980-2017. His empirical results showed a positive and significant effect of national income per capita, industry value added and trade openness on fiscal capacity. But, the effect of service sector is positive and statistically insignificant on fiscal capacity. In contrast, value added in the agricultural sector (%GDP) is negatively associated with fiscal capacity. In a similar analysis, Madreimov (2021) found a positive effect of regional GDP, fixed asset investment, tax arrears, and number of working taxpayers on tax revenue. His analysis finds a negative relationship between tax revenue and agricultural GDP. Several other works have reached similar conclusions. We can cite among others the work of Gyomai et al (2014), World Bank (2018), the International Monetary Fund (2018), Lawin (2020).

3. Data and Methods

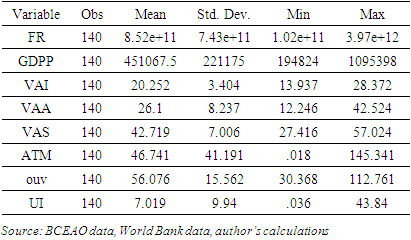

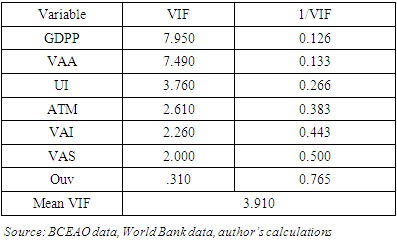

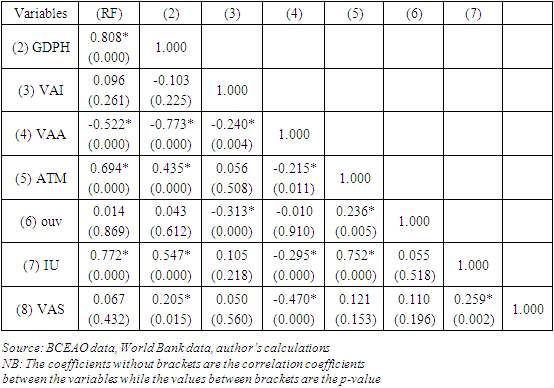

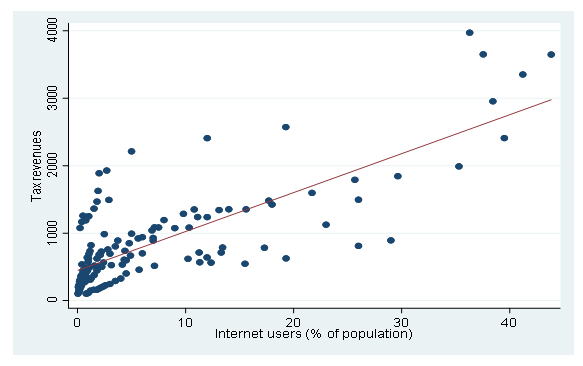

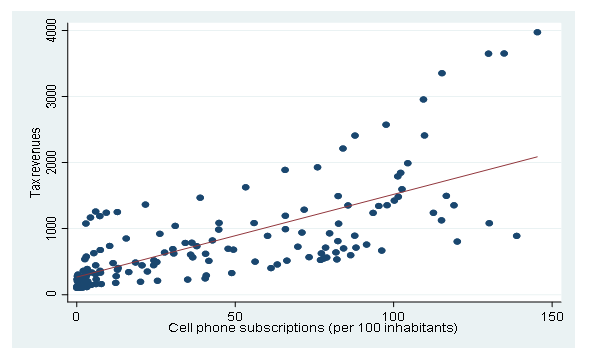

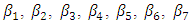

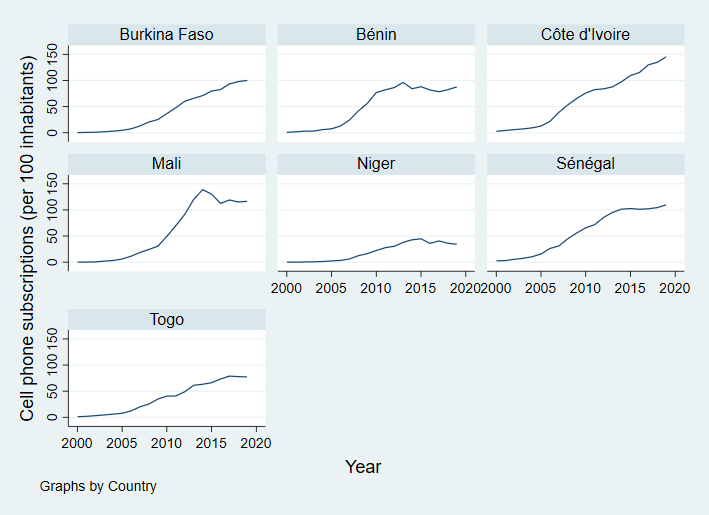

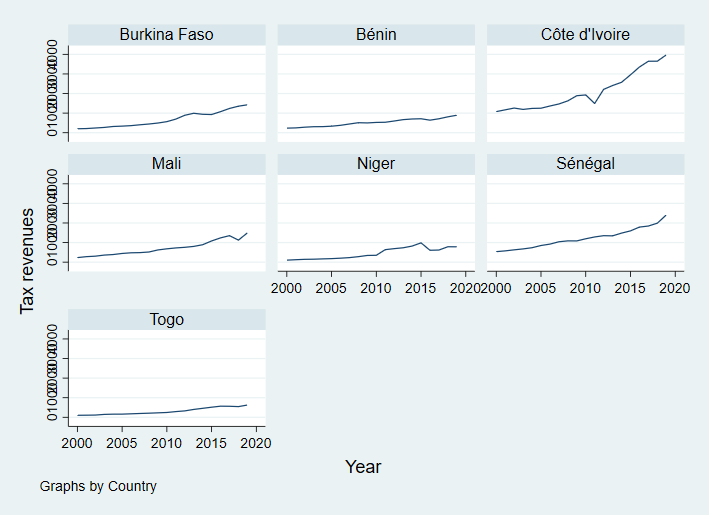

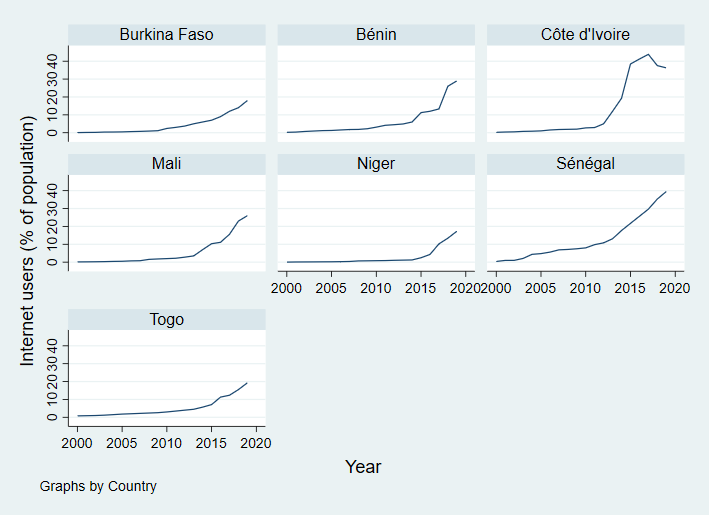

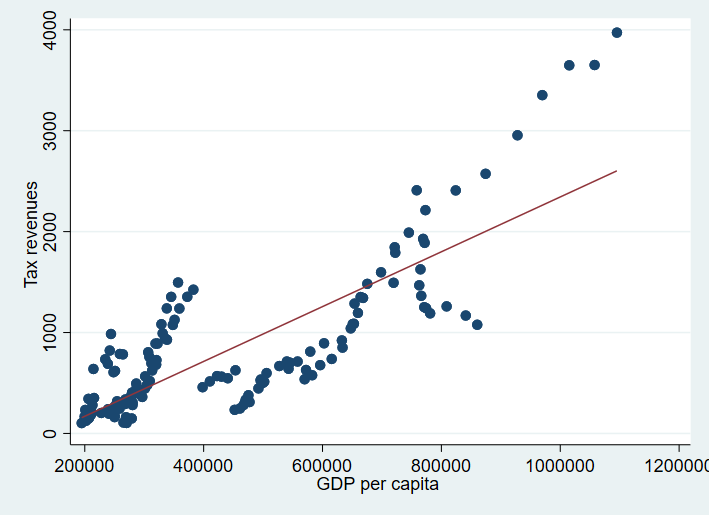

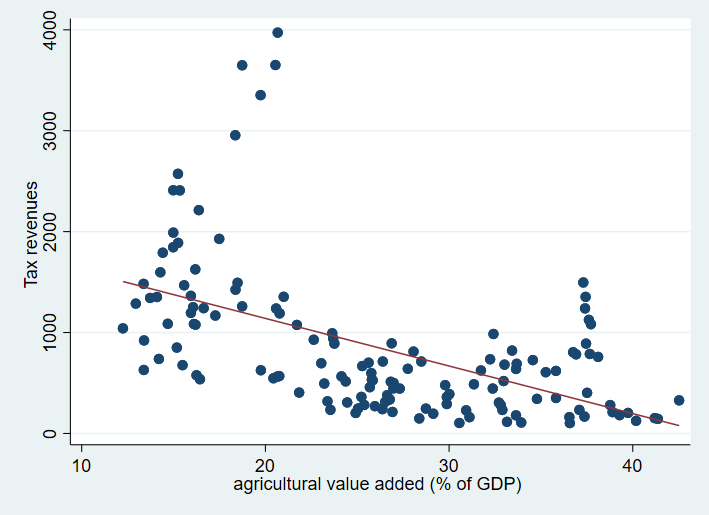

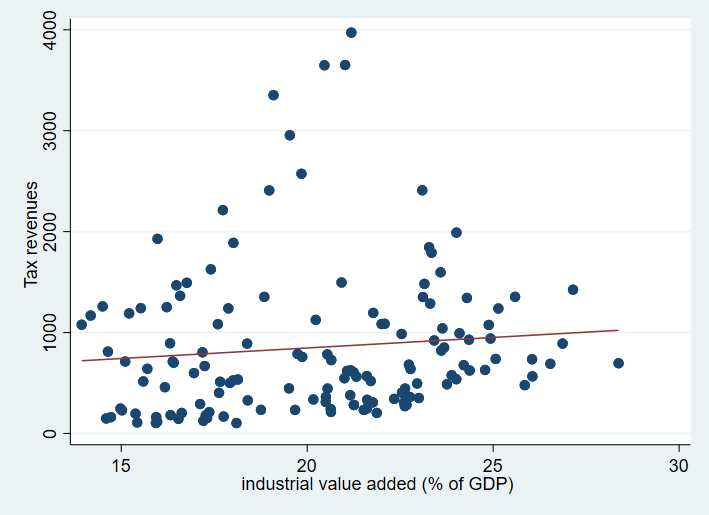

- Data Source This study uses a balanced panel of seven (7) WAEMU countries. The countries concerned by the study are Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Niger, Mali, Senegal and Togo. Guinea-Bissau is excluded from the analysis because of the lack of availability of data on this country for the period under review. Data on tax revenue (FR) and GDP per capita (GDPP) are from the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) database and from 2000 to 2019. while data on value added in the industrial sector (VAI; in %GDP), value added in the agricultural sector (VAA ; in %GDP), value added in the service sector (VAS; in %GDP), trade openness (ouv), Internet users (% of population) (UI), and cell phone subscriptions (per 100 inhabitants) (ATM) are taken from the World Bank database (WDI) for the same period. Central Bank of West African States. The countries included in the study are: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Niger, Mali, Senegal and Togo. Guinea-Bissau is excluded from the analysis because of the availability of data on this country for the period under consideration.The GDP per capita (GDPP) variable provides information on the level of per capita income, average purchasing power of the population, and wealth in an economy, and is expected to have a positive effect on fiscal capacity (Gyomai, et al. 2014; Canares, 2016; World Bank, 2018; International Monetary Fund, 2018; Lawin, 2020; Canares, 2016 ; Mallick, 2021). We refer to FR as the total tax revenue mobilized by each of the countries in the study in a year t, relative to GDP (in %GDP). These tax revenues include corporate taxes, income taxes, value-added taxes and taxes on foreign trade (VAT at the customs cordon, import and export customs duties). This variable is the explained or dependent variable. Per capita income is assumed to have a positive influence on revenue collection. The World Bank (2018), the International Monetary Fund (2018), and Mallick (2021) consider the value added on agricultural sector as a determinant of the level of tax revenue. Indeed, agriculture is difficult to tax, especially in African countries where the economy is dominated by the informal sector. In addition, most African countries grant an exemption on agricultural sector activities to encourage food production and address food insecurity. Thus, the share of agricultural sector value added in GDP is likely to have a negative effect on tax revenue realization. The value added of the industrial sector is an indicator of the level of industrialization of a country. This variable helps to assess the extent to which an improvement in the level of industrialization can contribute to higher tax revenues. Higher value added of the industrial sector is associated with higher fiscal capacity (Gyomai et al., 2014). Gyomai et al. (2014) showed that trade openness is positively associated with the ability to mobilize tax revenue. In developing countries, a large share of tax revenue comes from trade and customs taxes. Mallick (2021) has shown that trade openness puts nations in competition with each other to attract more investment and trade, thus promoting international trade and increasing tax revenues through exports. The introduction of variables such as access to the internet, access to cell phones in the model allows to highlight the effect of digitalization of the economy, development of ICT, e-governance on the efficiency in tax revenue mobilization.Problems arise in regressions when the explanatory variables are highly correlated. High levels of multicollinearity can lead to large variances in the least squares estimators (Mansfield et al., 1982; Lavery et al., 2019; Kim, 2019). To alleviate this problem, an analysis is done to assess the degree of multicollinearity between the explanatory variables. This analysis is done on the variance inflation factor (VIF). The advantage of knowing the VIF for each variable is that it gives users a tangible idea of the extent to which the variances of the estimated coefficients are affected by multicollinearity (Mansfield et al., 1982). The literature presents two decision criteria, namely: (i) an IFV value greater than 10 is an indicator of the presence of multicollinearity in the variables (ii) the average of all IFVs significantly greater than 1 is also considered an indicator of the presence of multicollinearity in the variables. However, the most widely used criterion is that of an IFV value ≥10 (Chatterjee et al., 2012 Kim, 2019; Mansfield et al., 1982; Lavery et al., 2019). The results of the test for this study are shown in the table 5. Although we have no VIFs greater than 10.Table 1 presents some descriptive statistics on the variables studied while Table 6 shows the correlation matrix between the variables studied. The analysis in Table 6 shows that GDP per capita, internet penetration, and cell phone penetration are positively and significantly correlated with tax revenues, while the positive correlation of value added in the industrial sector and trade openness are not significant. On the other hand, value added of the agricultural sector is negatively correlated with tax revenues. The scatter plots in Figure 1 and Figure 2 show a likely link between internet penetration, cell phone penetration and tax revenue mobilization. However, a multivariate analysis in an econometric framework will help to better situate the relationships.

|

| Figure 1. Tax revenues and internet users. Source: BCEAO data, World Bank data, author’s calculations |

| Figure 2. Tax revenues and cell phone subscriptions. Source: BCEAO data, World Bank data, author’s calculations |

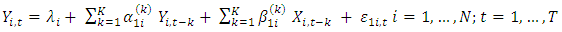

| (1) |

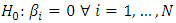

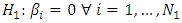

The alternative hypothesis assumes the existence of causality from X to Y for at least one country.

The alternative hypothesis assumes the existence of causality from X to Y for at least one country.

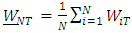

The null and alternative hypothesis of causality from y to x is specified in the same way. To test these hypotheses, Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) propose a procedure that involves running the N individual regressions of the model and performing F-tests of the K linear hypotheses

The null and alternative hypothesis of causality from y to x is specified in the same way. To test these hypotheses, Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) propose a procedure that involves running the N individual regressions of the model and performing F-tests of the K linear hypotheses  to recover the individual Wald statistic

to recover the individual Wald statistic  and finally to compute the average Wald statistic

and finally to compute the average Wald statistic  :

:  | (2) |

are the individual Wald statistics for the Granger causality test. Assuming that the statistics

are the individual Wald statistics for the Granger causality test. Assuming that the statistics  are independent and identically distributed, we calculate a standardized statistic, Z-bar:

are independent and identically distributed, we calculate a standardized statistic, Z-bar: | (3) |

| (4) |

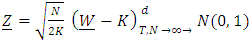

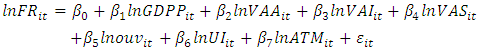

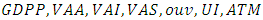

the endogenous variable of the model and

the endogenous variable of the model and  the exogenous variables of the model and

the exogenous variables of the model and  the error term,

the error term,  is the constancy,

is the constancy,  are parameters to be estimated, and

are parameters to be estimated, and  is the logarithmic function.The choice of the model used is guided by the structure of the data used and the period over which the data are available. For this study, we have an individual dimension (N) equal to 7 and a temporal dimension (T) equal to 20, which is a limit to the use of the GMM and ARDL models. The generalized method of moments (GMM) has certain conditions that this study falls far short of. The first condition assumes a large number of individuals relative to the period. This method is rejected because of the very small number of countries relative to the period in this study. The theory supporting the estimation of the GMM model would like the T/N ratio to converge asymptotically to 0, in order to have a good property of the estimators (Kiviet, 1995; Arellano et al., 1991; Ahn et al., 1995; Alvarez et al. 2003). This assumes that N is of a magnitude greater than T. A limitation to the use of the ARDL model in this study is that the estimation of an ARDL model requires a long series per individual to ensure a good result of the stationarily tests of the variables.We thus proceeded to the specification of a fixed effect or random effect model. The choice of a fixed or random effect model is based on the verification of certain hypotheses. The Breusch-Pagan test or Lagrange multiplier test is used to empirically validate the choice of a compound error structure. This test precedes the Hausman test which deals with the specification of individual effects in a panel. It is used to discriminate between fixed and random effects (Baltagi, 2008). Under the null hypothesis, the H statistic follows a chi-square distribution with k degrees of freedom (where k is the number of explanatory variables). The null hypothesis of the presence of random effects is accepted if the H-statistic is less than the critical value read from the Chi-square table or if the probability of Chi-square is greater than 5%. The Jarque-Bera test is used to determine if the residuals from the chosen regression model follow the normal distribution.

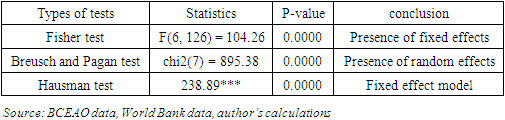

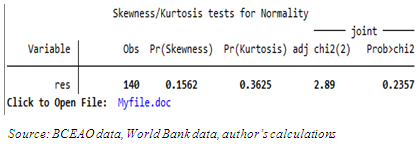

is the logarithmic function.The choice of the model used is guided by the structure of the data used and the period over which the data are available. For this study, we have an individual dimension (N) equal to 7 and a temporal dimension (T) equal to 20, which is a limit to the use of the GMM and ARDL models. The generalized method of moments (GMM) has certain conditions that this study falls far short of. The first condition assumes a large number of individuals relative to the period. This method is rejected because of the very small number of countries relative to the period in this study. The theory supporting the estimation of the GMM model would like the T/N ratio to converge asymptotically to 0, in order to have a good property of the estimators (Kiviet, 1995; Arellano et al., 1991; Ahn et al., 1995; Alvarez et al. 2003). This assumes that N is of a magnitude greater than T. A limitation to the use of the ARDL model in this study is that the estimation of an ARDL model requires a long series per individual to ensure a good result of the stationarily tests of the variables.We thus proceeded to the specification of a fixed effect or random effect model. The choice of a fixed or random effect model is based on the verification of certain hypotheses. The Breusch-Pagan test or Lagrange multiplier test is used to empirically validate the choice of a compound error structure. This test precedes the Hausman test which deals with the specification of individual effects in a panel. It is used to discriminate between fixed and random effects (Baltagi, 2008). Under the null hypothesis, the H statistic follows a chi-square distribution with k degrees of freedom (where k is the number of explanatory variables). The null hypothesis of the presence of random effects is accepted if the H-statistic is less than the critical value read from the Chi-square table or if the probability of Chi-square is greater than 5%. The Jarque-Bera test is used to determine if the residuals from the chosen regression model follow the normal distribution.4. Results and Discussion

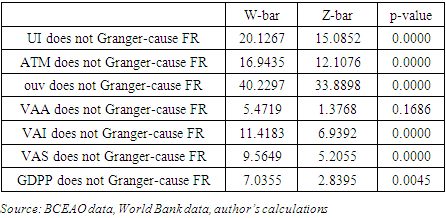

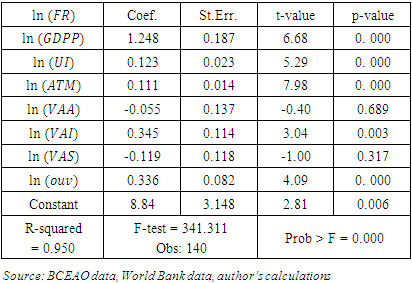

- The causal relationship between cell phone penetration, internet penetration and tax revenues is examined using the panel causality test of Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012). The estimation results show the existence of a causal relationship between cell phone penetration and tax revenues on the one hand and between internet access and tax revenues on the other. Indeed, the probability associated with each of the estimated parameters of the variables measuring ICT is almost zero (0.0000), a value well below 5%, the threshold considered. This result means that the null hypothesis that cell phone penetration does not influence tax revenue mobilization is rejected. In other words, we have almost zero probability of being wrong that cell phone penetration does not influence tax revenue mobilization in the WAEMU. Similarly, the null hypothesis that Internet access does not influence tax revenue mobilization is rejected. Overall, cell phone access and internet access are predictive of tax revenue mobilization in the WAEMU. The results show that industrial value added, trade openness, and GDP per capita drive tax revenue. However, the results do not provide enough evidence to conclude that there is a causal relationship between agricultural value added and tax revenue. The actual effects of each of these variables on tax revenue are estimated and presented in Table 2.

|

|

|

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study empirically examines the relationship between internet accesses, cell phone access and tax revenue mobilization in WAEMU countries. Specifically, the study examines, on the one hand, the existence of a causal relationship between the Internet penetration rate and tax revenues, and the existence of a causal relationship between the cell phone penetration rate and tax revenues. On the other hand, it assesses the effect of these two variables, indicators of ICT development, on tax revenues. The causality relationships were examined using the panel causality test of Dumitrescu and Hurlin, (2012) while the effects were examined using a fixed effect panel model.The results show that there is a causal relationship from cell phone access or penetration to tax revenue and a causal relationship from internet penetration to tax revenue. The econometric results showed that a 10% increase in internet penetration increases tax revenues by 1.23%, while a 10% increase in cell phone penetration increases tax revenues by 1.11%. It also appears that a 10% increase in the value added of the industrial sector increases tax revenues by 3.45%, while a 10% increase in trade openness increases tax revenues by 3.36%. The effects of the value added of the agricultural sector and the value added of the service sector on tax revenues were found to be negative and insignificant. Ultimately, tax authorities in WAEMU countries can take advantage of the facilities and opportunities that new information and communication technologies offer today to interact with taxpayers in the collection, administration and compliance of taxes and the control of corruption, in order to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of tax administration.At the end of this study, we recommend that WAEMU countries invest more in the digitalisation of the economy and the tax system. They should invest in the development of new information and communication technologies and communicate more on the use of digital platforms that tax administrations have put in place to facilitate tax formalisation and declaration procedures. WAEMU countries must facilitate access to good quality internet, access to mobile telephony (a tool for facilitating mobile money payments) in order to mobilise the resources necessary for sustainable development in area. The countries of the zone must give more support to their industrial sector, the sector that brings more taxpayers to the State. Tax administrations in WAEMU countries should conduct awareness campaigns on tax compliance using cell phones, in order to reach taxpayers and their associations directly, especially those in the service and agricultural sectors. They can also produce visual videos of how to pay taxes online or by cell phone.However, this study has a limitation. The fact that the good governance indicator is not included in the model is a limitation of this study. Indeed, good governance can help ensure the efficiency of public service delivery. Thus, future studies can examine the influence of good governance on the efficiency of tax revenue mobilization in the WAEMU area.

Conflict of Interest Statement

- The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

- The data used for the estimates do not include confidential information about individuals or animals that may raise ethical concerns.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank all those who have contributed to the improvement of the quality of this paper. Special thanks to all reviewers.

Consent for Publication

- The author grants his consent for publication of this paper.

Funding

- The writing of this paper has not been funded or sponsored. It was done at the author’s expense.

Data Availability Statement

- The data used in this paper is fully available and can be accessed upon request.

Appendix

| Figure 3. Cell phone subscriptions from 2000-2019, Source: BCEAO data, World Bank data, author’s calculations |

| Figure 4. Tax revenues from 2000-2019, Source: BCEAO data, World Bank data, author’s calculations |

| Figure 5. Cell phone subscriptions from 2000-2019, Source: BCEAO data, World Bank data, author’s calculations |

| Figure 6. Tax revenues and GDP per capita, Source: BCEAO data, World Bank data, author’s calculations |

| Figure 7. Tax revenues and agricultural value added, Source: BCEAO data, World Bank data, author’s calculations |

| Figure 8. Tax revenues and industrial value added; Source: BCEAO data, World Bank data, author’s calculations |

|

|

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML