-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2022; 12(2): 40-48

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20221202.02

Received: Aug. 7, 2022; Accepted: Aug. 23, 2022; Published: Sep. 28, 2022

Modeling Electrical Energy Security and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Performance in Nigeria

Abdulgaffar Muhammad1, Edirin Jeroh2, Owolabi Akanni Atanda3

1Data Analyst and Consultancy, Nigeria

2Department of Accounting, Faculty of Management Sciences, Delta State University, Abraka

3Ph.D Candidate, Delta State University, Abraka

Correspondence to: Abdulgaffar Muhammad, Data Analyst and Consultancy, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Electrical energy security is best explained in terms of the accessibility and availability of electricity that determine the optimum production capacity and sustainable economic growth of a country. The sole objective of this study is to model the link between energy security and GDP performance in Nigeria. Secondary data was collected from World Bank publications from the period of 1990 to 2020 for the analysis of this work. Econometric models like the unit root test, vector autoregressive (VAR) model, cointegration model, Granger causality, and impulse response function were applied for the analysis of this study. The unit root test shows that all the variables such as electrical energy security tools and GDP performance become stationary after the first difference, which suggests that a further econometric approach can be applied. The VAR model and cointegration show that there is a significant link between electrical energy security and GDP performance in Nigeria in the short and long run. The Granger causality test reveals that electrical energy security substantially contributed to the GDP performance in Nigeria, while the impulse response function shows that the impulse response of electricity availability to GDP shocks indicates a negative response while the import response of electricity consumption to GDP shocks indicates a positive response. This suggests that electricity consumption demand is currently above the amount of electricity available or generated in the country. Therefore, there is a need for the government of Nigeria to adopt renewable energy options aside from the primary source of electricity to improve energy security standards that will bring about sustainable economic growth and development as well as mitigate the high poverty level in Nigeria.

Keywords: Electrical energy security, GDP Performance, Unit root test, VAR model, Cointegration model, Granger Causality, Impulse response

Cite this paper: Abdulgaffar Muhammad, Edirin Jeroh, Owolabi Akanni Atanda, Modeling Electrical Energy Security and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Performance in Nigeria, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 12 No. 2, 2022, pp. 40-48. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20221202.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Energy security contributed immensely to economic growth because it served as a driving tool for the economy and national development of any nation in the world (United Nations, 2016). The security of electrical energy is guaranteed in terms of energy production or availability, accessibility to electricity, and electricity consumption based on the user’s level of affordability (Igbokoyi, 2016). It is no longer news that despite the development of many rural and urban areas in Nigeria today, the recent hike in the electricity tariff has hampered the accessibility of many Nigerians, private companies, and businesses to electricity, which has caused many productions of goods and services to decline drastically (IEA, 2020). The economy is better driven with a high level of production capacity, increased exportation, and government protection on locally made goods to discourage importation, resulting in a favorable balance of payments and outstanding GDP performance in the country (World Bank, 2022). Due to low electricity availability, poor accessibility due to a flawed electricity distribution infrastructure, and the current pricing increase, Nigeria is faced with an issue with the security of its electrical energy supply (Ajao and Adeogun, 2021). Businesses and investors have moved in large numbers to nations with good access to and supply of power (Dike, 2017). Due to their significant commitment to obtaining power to run their separate enterprises, many employers in Nigeria could not afford high wages, which has resulted in a high level of unemployment and even the underutilization of employees (Okeke and Izueke, 2015). Furthermore, the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 had an impact on the global economy, including Nigeria (World Health Organization, 2020). The lockdown crippled a lot of businesses, and government revenue was negatively affected because economic activities were stalled during this period. The electrical energy security that would have been better guaranteed by the government could not be feasible because of the economic recession, which was further aggravated as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. Many countries around the world take electrical energy security seriously because it helps to attract foreign investors, expand production capacity, and enable long-term development (World Bank, 2022). Different studies have worked on highlighting energy security's effect on the economy as it contributed to sustainability development but no research has been able to model the connection between electrical energy security and the gross domestic performance in Nigeria sufficiently using econometric models. Therefore, this research study's sole objective is to model the link between electrical energy security and GDP performance in Nigeria using econometric models. As such, this study contributes greatly to the existing body of knowledge.

2. Literature Review

- This section is divided into two major parts which is the theoretical and empirical literature review.

2.1. Theoretical Review

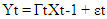

- Every developed country has better economic growth and national development with sustainable energy security, according to the energy security theory by Igbokoyi and Iledare (2016). It is therefore important to establish the theory that best describes the link between energy security and GDP performance as a proxy for economic growth. In essence, the first equation is expressed as follows to describe energy security:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

2.2. Empirical Literature

- This section explores the empirical link between electrical energy security and gross domestic performance in Nigeria. Quite a few empirical studies were discussed in this section to critically examine the link between electrical energy security and economic growth. Muhammad, Haider, and Anam (2022) analyzed the impact of electricity consumption on three European Union member countries’ economic growth, that is, France, Portugal, and Finland. The study used co-integration analysis and empirically indicates a positive impact of electric power consumption on economic growth in the long and short run in Portugal and Finland, and only in the long run in the case of France. Hence, the study concludes that electric power consumption has appeared to be an essential factor in elevating economic growth across the selected countries. Belal, Ahmed, S. & Boujedra (2021) explored the causality between industrial electricity consumption and economic growth in Saudi Arabia. The study used a causality test for a sample period from 1990 to 2019. The study found that there is one-way causality from industrial electricity consumption to economic growth in Saudi Arabia. Similarly, Hazarika (2020) examined the causal relationship between electricity consumption and economic growth in India. The study considered a period between1991 and 2018 and the study found a causation direct relationship from electricity consumption and economic growth. Adegoriola and Agbanuji (2020) evaluated the impact of electricity consumption on the economy of Nigeria from 1986 to 2018, using an autoregressive distributed lag model as an estimation technique. The study revealed that electricity consumption and the rate of economic growth are significantly and positively correlated in the short-run; however, in the long-run, electricity consumption has a negative and insignificant impact on economic growth in Nigeria, while the cost of fuel and gas exerts an insignificant but positive impact on economic growth. Using various econometric approaches, Faisal, Tursoy, Resatoglu, and Berk (2018) examined the relationship between electricity consumption, economic growth, urbanization, and trade on the Icelandic economy. The study confirmed that economic growth has a positive effect on electricity consumption in both the short and long run. The study also indicated an absence of a grand causality nexus linking economic growth and electricity use. Similarly, Twerefou, Iddrisu, and Twum (2018) analyzed the relationship between electricity consumption and economic growth using both Granger causality and panel co-integration techniques. The study implied that in the long run, economic growth is statistically and significantly affected by electricity utilization. Also, the study verified a one-direction causality nexus moving from GDP to electricity utilization. Tariq, Javaid, and Haris (2018) analyzed the effect of electricity consumption on economic growth by obtaining macroeconomic data from four developing countries (which include India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Pakistan) spanning from 1981 to 2015. The study analyzed the data using a random effect approach and robust OLS estimation techniques and therefore observed that the two variables (economic growth (GDP) and energy consumption) are positively correlated. Shereef (2017) evaluates the relationship between electricity consumption and economic growth. The findings from the Granger causality analysis revealed a one-direction nexus running from GDP to electricity utilization. It is therefore concluded by the study that the demand for electricity consumption is largely determined by economic growth. Stern, Burke, and Bruns (2017) did a macroeconomic review of the impact of electricity on economic development by obtaining panel data from 136 countries. The variables were analyzed using cross-sectional regression analysis, which revealed a strong impact of electricity consumption on the development of the countries under review. Okorie and Manu (2016) evaluate the effect of electricity consumption on economic growth by obtaining macroeconomic data spanning between 1980 and 2014 and analyzing the variables observed in the study using VAR-based and Johansen co-integration techniques. According to the study, electricity use has a significant impact on economic growth in both the short and long term. Oyuke and Peter (2016) conducted research on the lack of access to electricity in most developing nations, especially among Africans, and found that this was caused by off-grid energy-related problems, which also contributed to the region's typical epileptic power supply. As a result, this study used econometric models to analyze the relationship between GDP performance (a proxy for economic growth) and electrical energy security measures, such as accessibility, availability, and power consumption. The body of knowledge has been significantly expanded by this methodology.

3. Data and Methodology

- This section is divided into description of data used and the methodology adopted for the study.

3.1. Data

- For the analysis of this work, secondary data from the World Bank Development Indicator (data.worldbank.org) covering the period from 1990 to 2020 was used. This study used a quantitative study design. Due to the availability of data and the purposive sample method, the GDP performance and energy security variables (such as access to electricity, electricity availability, and electricity consumption) were chosen.

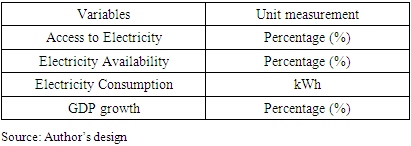

|

3.2. Methodology

- Summary statistics (such mean and standard deviation) and econometric model approaches like the unit root test, vector autoregressive (VAR) model, Johansen cointegration, impulse response function, and Granger causality test are the methods of analysis used in this work.

3.3. Model Specification

3.3.1. Unit Root Test

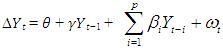

- The presence of a unit root indicated that the series is not stationary, which may yield erroneous findings if not eliminated. The test is carried out to eliminate the possibility of erroneous results. The unit root test hypothesis is stated below as: H0: there is an existence of a unit root vs Ha: there is no unit root (the variable is stationary). The augmented dickey fuller (ADF) test can be presented mathematically as:

Where, 𝜃 is a constant, 𝛾 is the coefficient of process root,

Where, 𝜃 is a constant, 𝛾 is the coefficient of process root,  coefficient in time tendency, 𝑝 is the lag order and 𝜔𝑡 is the disturbance (error) term.

coefficient in time tendency, 𝑝 is the lag order and 𝜔𝑡 is the disturbance (error) term. 3.3.2. Cointegration Analysis

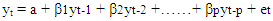

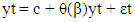

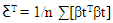

- Johansen cointegration test is an approach for testing cointegration of integrated variables with zero level I (0), order 1, I (1)- after first difference or of order 2, I (2)-after second difference. This test permit more than one cointegrating relationship. There are two types of Johansen test which are the trace and max eigen value, and they form the basis of the inference or decision and their result might be little different from other. The Var model indicated by Var(p) is mathematically defined in a general term below as:

It is important to note that the variables should be stationary before proceeding to Johansen Cointegration test. When there is cointegration, it means there is a long run association between the variables.

It is important to note that the variables should be stationary before proceeding to Johansen Cointegration test. When there is cointegration, it means there is a long run association between the variables. 3.3.3. Vector Autoregressive (VAR) Model Estimation

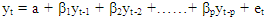

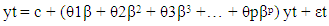

- VAR model is actually a quantitative econometric approach that examine the short run relationship between the variables. All the variables in vector autoregressive model are treated as endogenous variables. Meanwhile the generalized VAR model can be written as

and can be written with the corresponding lags as

and can be written with the corresponding lags as  VAR can therefore be expressed as follows:

VAR can therefore be expressed as follows:  | (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

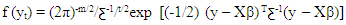

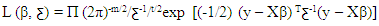

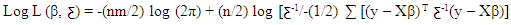

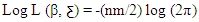

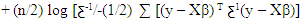

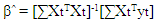

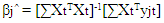

3.3.4. Estimation of VAR Model Parameter

- Two methods such as maximum likelihood and ordinary least square can be adopted to estimate the parameter (p) of VAR. The maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) is used for the parameters estimation of a model known as density function by maximizing the likelihood function for the observation is:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

The estimates obtained results

The estimates obtained results  | (8) |

is

is  | (9) |

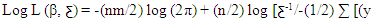

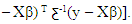

Log likelihood function is

Log likelihood function is

Parameter estimate for

Parameter estimate for  using MLE is

using MLE is  | (10) |

3.3.5. Impulse Response Function

- An impulse response function (IRF) in econometrics measures the effect of a shock to an endogenous variable on itself or another endogenous variable using a graphical approach. It is noteworthy that the vector autoregression (VAR) model was first estimated before computing the impulse response function.

3.3.6. Granger Causality Test

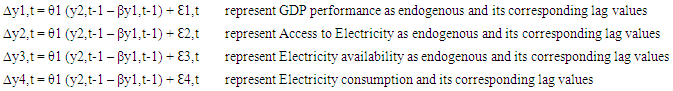

- The study used the Granger causality test to analyze the causal connection of the variables, focusing primarily on the causal link among the variables of interest. X causes Y (using arrow direction: Energy security→GDP Performance). This research will look at whether X causes Y or not. The Granger causality test will also disclose the impact of energy security indicators (Xi) on the GDP Performance (Y) in Nigeria. Granger causality is an econometric approach used for prediction and have two time series X and Y using vector autoregressive (VAR) model. The VAR model is made up of two equations:

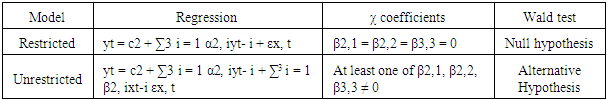

|

4. Results and Discussion

- This section presents results of analysis and the discussion of notable findings. EViews version 11 and Stata software version 16 were used for the analysis of this research study.

4.1. Results

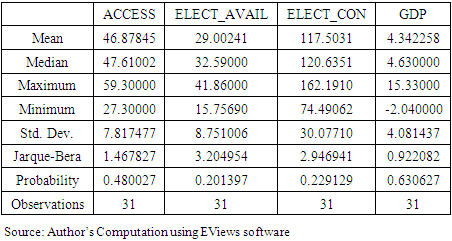

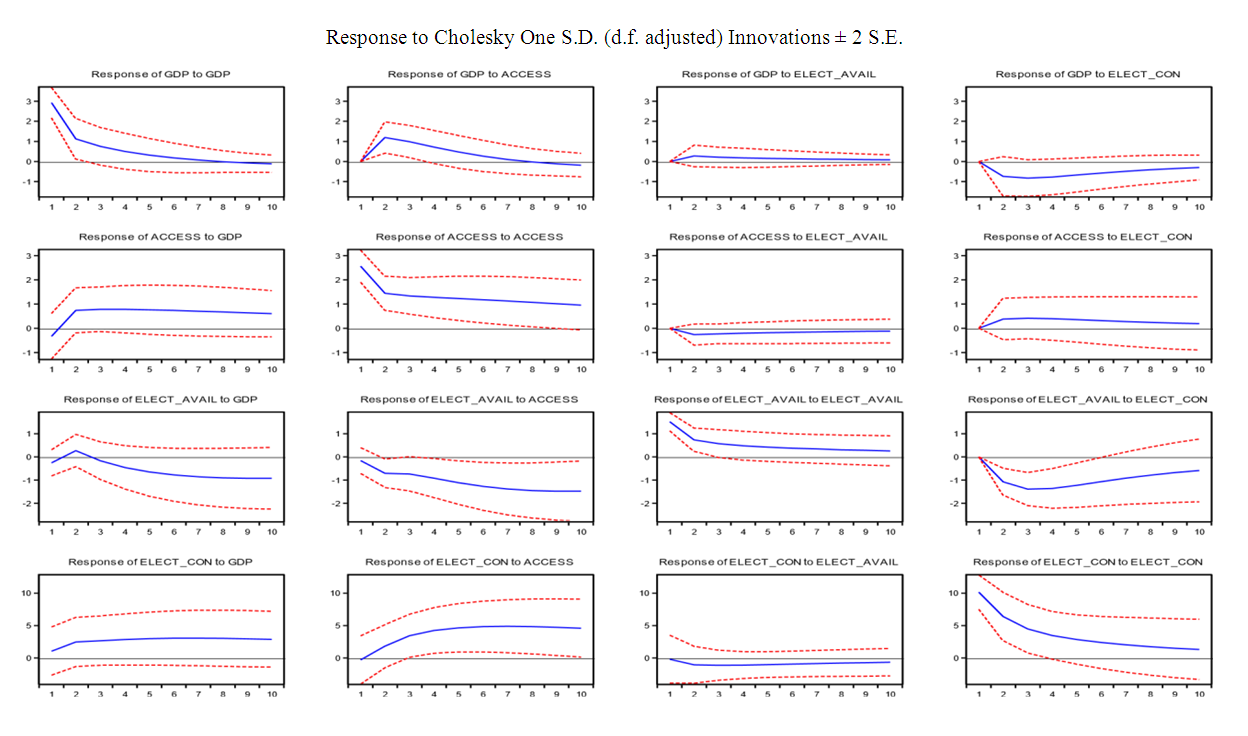

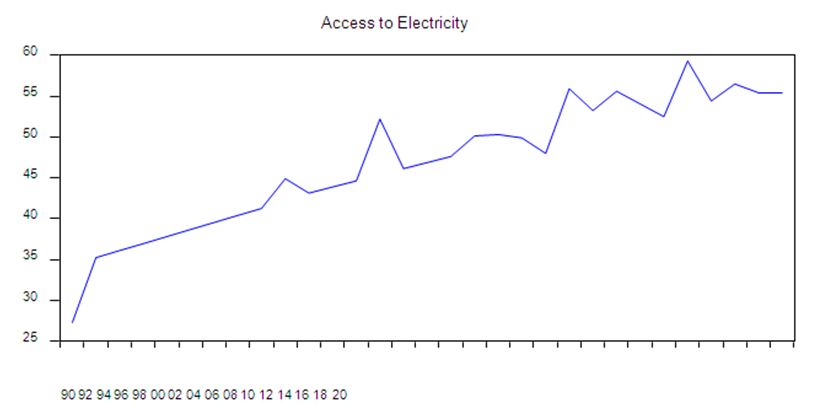

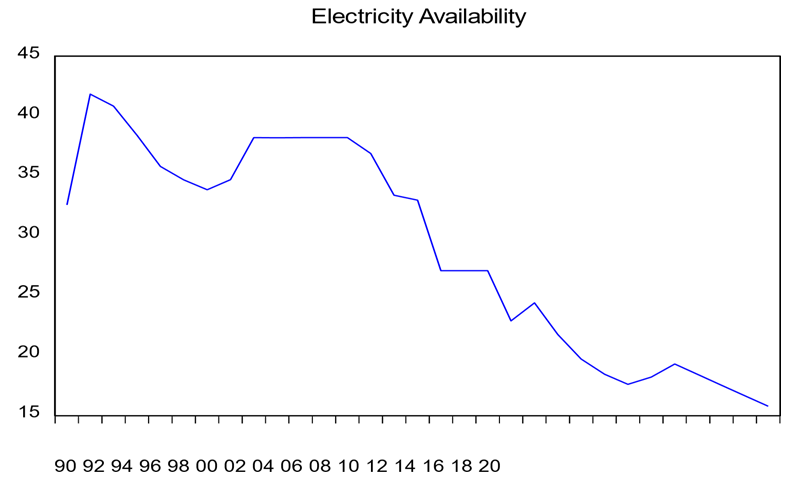

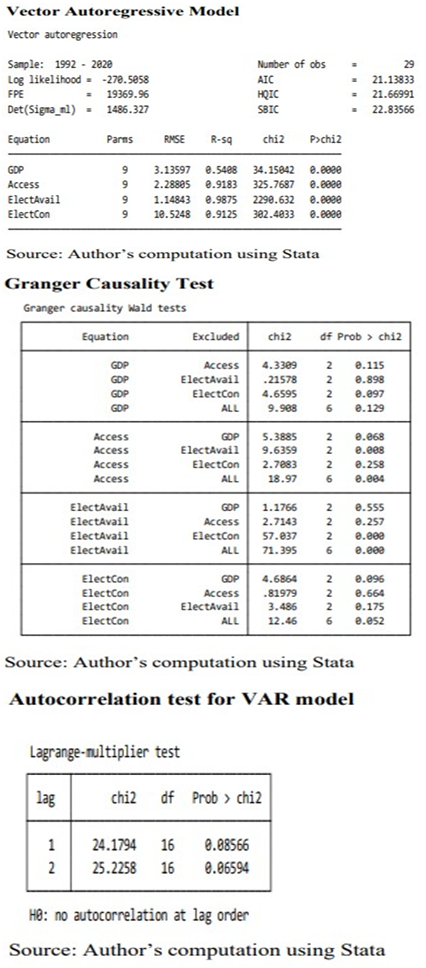

- Table 3 shows that average access to electricity by Nigerians is about 47% with variability of about 8%. The average electricity availability is 29% with variability of about 9%, the average electricity consumption is about 118 kWh with variability of about 30 kWh while the average GDP performance is about 4.3% with variability of about 4.1%.

|

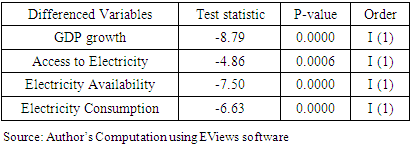

|

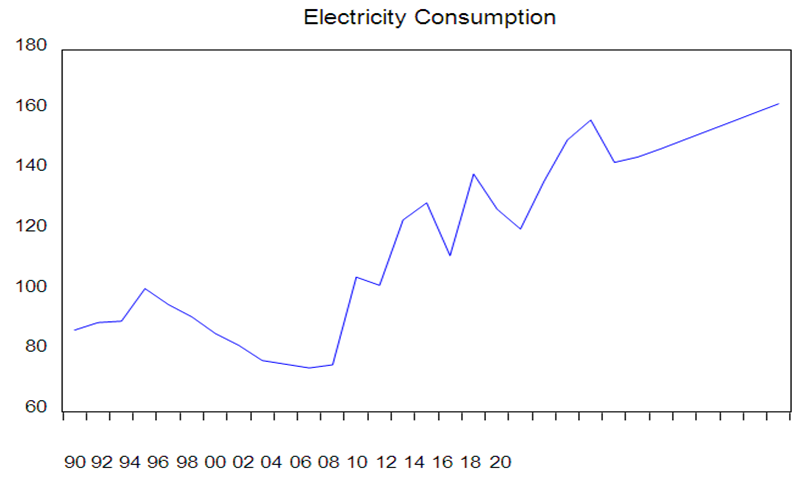

4.2. Vector Autoregressive (VAR) Model

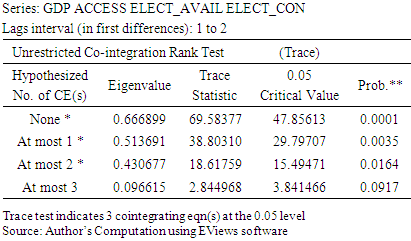

- In the appendix, which contains the results of the vector autoregression, we can see that each endogenous variable has nine parameter values, all of which are statistically significant at the 1% level of significance and have relatively high R-square. This indicates that, in the short run, there is a significant relationship between GDP growth, access to electricity, the availability of electricity, and electricity consumption. Additionally, the Langrage multiplier test for the error term's independence demonstrates that there is no autocorrelation at the first order level, supporting the premise that a vector auto regression model should be used (see appendix). Table 5 shows the result of the Johansen cointegration test and we can see that three of the cointegrating equations such as None*, At most 1* and at most 2* are statistically significant at 5% level and this follows that there is a long-term connection between GDP growth, Access to Electricity, Electricity availability and Electricity consumption.

|

4.3. Granger Causality

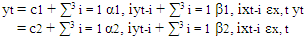

- The appendix contains the Granger causality test results, which demonstrate that while each energy security tool—such as access to electricity—causes GDP performance at a 10% level, they jointly account for ALL of it, including GDP performance growth at a 1% level. Additionally, ALL includes GDP performance at a 1% level of significance while power is available, whereas ALL includes GDP performance at a 10% level of significance when electricity is consumed. This implies that Nigeria's energy security has a significant causal impact on GDP growth.Figure 1 shows the impulse response function for all the endogenous variables in the blue line, and it falls within the two 95% confidence intervals, which are the red lines. More so, the impulse response of Access to electricity to GDP shocks falls between the two 95% confidence intervals and indicated a positive response. It is noteworthy that the line below zero shows a negative response while the one above the zero line shows a positive response. The impulse response of electricity availability to GDP shocks falls between the two 95% confidence intervals but falls below the zero line, which indicates a negative response, while the import response of electricity consumption to GDP shocks also falls between the two 95% confidence intervals and is above the zero line, which indicates a positive response.

| Figure 1. Impulse Response Function |

| Figure 2. Graph of GDP Performance |

| Figure 3. Graph of Access to Electricity |

| Figure 4. Graph of Electricity Availability |

| Figure 5. Graph of Electricity Consumption |

4.4. Discussion of Findings

- As a result of the analysis above, the vital findings of the result will be discussed below. The unit root test was used in conjunction with the augment dickey-fuller method, and it demonstrates that all variables are integrated in order one. This suggests that further econometric models can be adopted. The vector autoregressive model was applied, and it shows that in the short run there is a significant link between GDP growth, access to electricity, electricity availability, and electricity consumption. The assumptions of normality and autocorrelation of error terms associated with the VAR model was also satisfied. The Johansen cointegration test was employed, and it shows that there is a long-run association between GDP performance and energy security, which is very consistent with the studies of Adegoriola and Agbanuji (2020); Faisal et al. (2018); Okorie and Manu (2016). The Granger causality test was also performed, and it shows that electricity availability causes ALL economic outcomes, including GDP performance, at a 1% level of significance while electricity consumption causes ALL economic outcomes, including GDP performance, at a 10% level of significance. This follows that energy security in Nigeria substantially has a causal effect on the GDP performance, which agrees with the work of Muhammad, Haider, and Anam (2022). Stern, Burke, and Bruns (2017). Shereef (2017). Conclusively, the impulse response function for all the endogenous variables is the blue line, and it falls within the two 95% confidence intervals, which are the red lines. More so, the impulse response of access to electricity to GDP shocks fell between the two 95% confidence intervals and indicated a positive response. It is noteworthy that the line below zero shows a negative response while the one above the zero line shows a positive response. The impulse response of electricity availability to GDP shocks falls between the two 95% confidence intervals but falls below the zero line, which indicates a negative response, while the import response of electricity consumption to GDP shocks also falls between the two 95% confidence intervals and is above the zero line, which indicates a positive response.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implication

- Energy security is a vital driver of the economic growth of every country, including Nigeria, that wants to grow and also maintain sustainable national development. The primary purpose of this work is to model the link between electrical energy security and GDP performance using an econometric approach. The vector autoregressive model and Johannsen cointegration was employed, and it shows that there is a significant link between GDP performance and electrical energy security both in the short run and long run. The graph of electricity consumption shows an upward trend movement, while the graph of electricity availability shows a downward trend movement. The impulse response of electricity availability to GDP shocks indicates a negative response while the import response of electricity consumption to GDP shocks indicates a positive response. This suggests that the availability of electricity in Nigeria is currently low compared to what is being consumed by the industries, businesses, and foreign investors to sustain their respective business activities. Consequently, the Nigerian government should develop a better energy policy that will adopt renewable energy such as hydropower, solar, wind, etc. as an alternative to our primary electricity generation source to improve energy security standards that will bring about sustainable economic growth as well as mitigate the high poverty level in the country.

5.1. Strength and Recommendation for Future Studies

- This research study has shown a tremendous quality in the choice of econometric models adopted and the tables and graphs, but can also be improved by extending the study beyond Nigeria to other west African countries to have a broader view of the link between energy security and GDP performance in the west African community.

Appendix

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML