-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2020; 10(6): 433-440

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20201006.13

Received: Aug. 28, 2020; Accepted: Sep. 15, 2020; Published: Oct. 28, 2020

Export Diversification and Economic Growth for ECOWAS States

Grafoute Amoro

Associates Professors and Researchers at the Faculty of Economics and Management, Félix Houphouët-Boigny University Abidjan, Cocody, CoteD’Ivoire

Correspondence to: Grafoute Amoro, Associates Professors and Researchers at the Faculty of Economics and Management, Félix Houphouët-Boigny University Abidjan, Cocody, CoteD’Ivoire.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

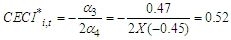

Our paper provide evidence on the relationship between export diversification and economic growth for the fifteen (15) countries of ECOWAS states from 2005 to 2015. We analyzed the effect and the nature of the relationship between Export diversification and economic growth. Using the dynamic panel data estimate method, we found that export diversification impact economic growth in ECOWAS states. However, the evidence of the link between export diversification and economic growth is non-monotonic (humped-shaped) relationship, which means that countries in ECOWAS can intensify export diversification in certain point at critical concentration export value=0.52 level, where income start to fall with export diversification portfolio. From that point the specification (concentration) should be intensify so as to increase income and pursue the higher growth.

Keywords: Export Diversification, Economic Growth, Dynamic panel data estimate

Cite this paper: Grafoute Amoro, Export Diversification and Economic Growth for ECOWAS States, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 10 No. 6, 2020, pp. 433-440. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201006.13.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Exports is one of the main factors enforcing economic growth of the countries. Exports of goods and services represent one of the most important sources of foreign exchange income that ease the pressure on the balance of payments and create employment opportunities. Thus Since the beginning of trade liberalization, in 1980’s, West African countries have promoted export growth strategy in order to stop the deterioration of economic performance and also take advantage of the opportunity the world was offering during the last decade of the 20th century in which world has seen the transformation of international trade and agreements. Particularly, the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, which led to the establishment and reforms of various bilateral and regional agreements. The event of World Trade Organization created the need for West African countries opportunities to diversify their export basket in order to maximize gains of international trade, which can be through introduction of new product to old markets; new products to new markets; and old products to new markets (Kamuganga, 2012). West Africa comprises of sixteen countries, which on May 28, 1975 established the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) It is a Regional Economic Communities (RECs) in order to coordinate and promotes trade, cooperation and sustainable development throughout West African countries. Furthermore the main objectives of ECOWAS were the elimination of all tariffs and non-tariffs barriers between members, the establishment of a customs union. In 1993 ECOWAS states has been revised, as one country such as Mauritania left the organization and also in order to broaden economic integration and increase political participation throughout West African countries. Currently it remains fifteen countries, where eight countries share a common currency (CFA)1, managed by the central bank BCEAO (banque centrale de l’afrique de l’ouest) within West Economic African Monetary Union (WEAMU).Our paper will investigated the role of export diversification on economic growth by using modern timex series. Whereas the theoretical and empirical literature on export-led growth is large, only a handful of empirical studies examine export diversification effects on economic growth. We will use the Generalized Method of Moment developed Arellano and Bond (1991) and Arellano and Bover (1995), it will overcome the gaps in the OLS estimator in conventional cross -sectional regressions.Our paper present in section 2 an overview movement between export diversification and economic growth for ECOWAS states. Section 3 gives the herfindahl export concentration index analysis following by literature review in section 4.The Model specification cover methodology and Data Source in section 5. Empirical estimated result and discussion of empirical findings have been mentioned in section 6 and 7 respectively. Section 8 gives the Findings implication based on our study result while section 9 gives conclusions.

2. Export Diversification and Growth in Ecowas States (1995-2013)

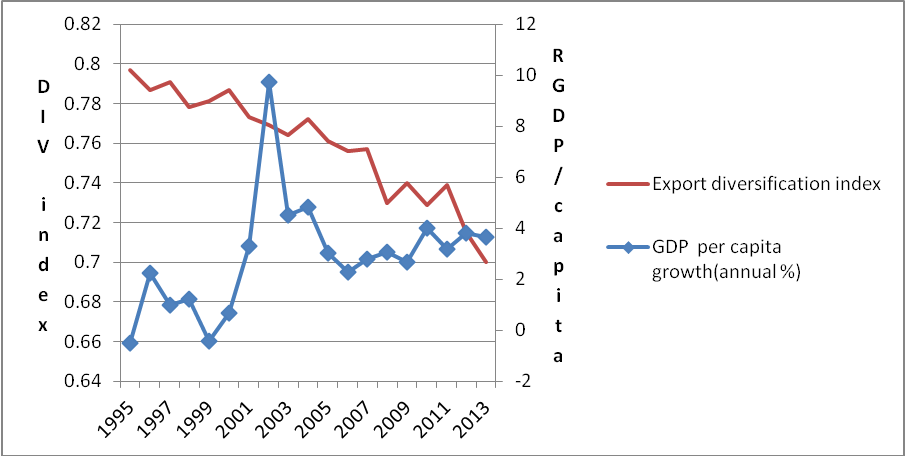

- Figure below shows the evolution of GDP per capita growth rate and export diversification index (EDI) between 1995-2013.

| Figure 2.1. Evolution of Real GDP per capita and EDI in ECOWAS states, 1995-2013 |

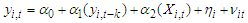

3. Herfindahl Export Concentration Index Analysis

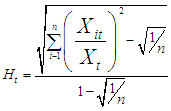

- A measure of export concentration; the Herfindahl Export Concentration Index is presented to be contrasted with the two measures of export diversification, and it is computed as follows:

Where;Ht is the concentration index in year t,Xit is the value of exports from sector i in year t,n is number of export sectors, and

Where;Ht is the concentration index in year t,Xit is the value of exports from sector i in year t,n is number of export sectors, and

| Figure 3.1. Herfindahl Export Concentration Index (1995-2013) (SOURCE: Computed from UNCTAD Statiscal bulletin) |

4. Literature Review

- Since the independence of African countries, many scholars and searchers studied different subjects about the Africa development issues. However minimal study has investigated the effects of export diversification on economic growth in West african countries. For instance, Christina Bartz (2010) has evidenced the positive link between Export diversification and Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Olaleye, Samuels Olasode (2013) using a granger causality test has confirmed the assertion of relationship between export diversification and economic growth in Nigeria. Evidence of export hypothesis for these fifteen countries in West Africa region integrated in Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) also has been inconclusive, thus warranting further investigation. In our study modern time series econometrics is used to examine both issues.Evidence of export hypothesis for fifteen countries in West Africa region, which integrated in Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) also, has been inconclusive, thus warranting further investigation.Yokoyama and Alemu (2009) see export diversification as a means of widening a country’s comparative advantage and further present three main theoretical arguments that may be considered in explaining the possible reasons why export diversification may positively affect economic growth. These are the traditional argument, the endogenous growth theory, and the structural models of economic development. These are subsequently discussed as follows.The traditional argument is of the view that less developed countries are exporters of a limited number of primary products which are highly vulnerable to international market demand. The instability in their export demand results in unstable export earnings, and since most developing countries depend to a very large extent on export earnings for income, growth in national income also becomes volatile. The point is that diversification of a country’s export portfolio has the ability to smoothen export earnings in the face of unstable world market conditions, thereby ensuring stability in income earnings. It has been argued that in the absence of export diversification, developing countries are highly likely to experience foreign exchange and balance of payments instability, which have negative implications for debt servicing, economic management and investment planning (Osakwe, 2007). These implications consequently create uncertainty in the macroeconomic front, thereby discouraging domestic investment, especially for risk–averse investors (Ali et al, 1991). For this reason, a more diversified export mix may enhance economic stability and growth of countries. Export diversification has therefore been projected for its ability to avert the problem of unstable foreign demand and thereby shielding developing countries from its detrimental economic consequences.From the perspective of the endogenous growth theory, aside the ability of export diversification to smoothen export earnings, it also has the capacity to bring about benefits in terms of new comparative advantage associated with the diversification of a country’s production structure. It is considered to widen the comparative advantage of developing countries from a few primary production sectors to higher value production sectors, which may result in better allocation of productive resources. The argument is further forwarded that through backward and forward linkages, new industries will be created through diversification of the production structure. Export diversification generates new production technologies and management efficiencies through international competition, thereby leading to increasing returns to scale and spillover effects which ultimately affect growth in the long-run. In effect, export diversification enables countries to benefit from dynamic gains from trade as it leads to an expansion in the production possibility frontier of the exporting economy. The structural models of economic growth indicate that in order to attain meaningful sustainable growth, export diversification policies should be targeted at moving away from primary commodities towards manufactured goods. This is likely to generate backward and forward linkages which are capable of creating new industries and expanding existing ones (Chenery, 1979; Syrquin, 1989). The structural argument seems to suggest that vertical export diversification possesses greater ability to impact growth as compared to horizontal export diversification. This suggests that the content rather than the number of products in a country’s export basket is very essential to its economic prosperity. Following Yokoyama and Alemu (2009), the means by which export diversification may influence a country’s national income or growth may be summarized in five (5) essential points as follows. First of all, since export diversification generates spillover effects in an economy, it may be considered as a production catalyst (a production factor) that increases the productivity of the other factors of production (Romer, 1990). Secondly, export diversification may increase income by expanding the possibilities to spread investment risks over a wider portfolio of economic sectors. Thirdly, export diversification is considered as a component of Total Factor Productivity (TFP) and is expected to exert positive impact on TFP growth, thereby promoting economic growth. Total Factor Productivity (TFP) has been identified as the single most influential factor affecting the growth of Sub Saharan (SSA) African countries (Fosu, 2012). Fourthly, export diversification may also have a positive effect on growth because of the existence of economies of scope in production. This exists when a given level of inputs generates greater inputs per unit profits when spread across many outputs than when dedicated to any one output. Finally, through forward and backward linkages, production of a diversified export structure is also likely to induce the creation of new industries and expansion of existing ones in the economy. Notwithstanding the various arguments and the theoretical explanations forwarded for the channel through which export diversification translates into growth, the evidence as to whether export diversification impacts growth for countries and regions of the world remains an empirical issue. Our study will evidence the impact of the diversification effect- on growth. We also test the hypothesis of a hump-shaped relationship between export diversification and economic growth. Since, there are available theoretical and empirical literature largely talks about a hump-shaped relationship between export diversification and growth (see Imbs and Wacziarg, 2003; Aditya and Roy, 2007; Hesse, 2008); meaning that export diversification would promote economic growth to a point beyond which it would slow down growth. The point beyond which export diversification slows the pace of growth is referred to as the Critical value of export concentration Index (CECI*). Interestingly, most of the empirical literature on export diversification and growth in West Africa has not considered testing the hump-shaped relationship; hence the critical level of export concentration index (CECI) for West Africa remains unknown. Knowledge of the CECI for West Africa is essential because it would help determine appropriate policy prescriptions regarding export diversification. Thus, investigating how much a dynamic and well diversified export basket has contributed to West African countries economic performance will aid governments from other African countries nations and economic development agencies in designing and implementing more appropriate pro-growth policies. These lessons can be particularly important for all Sub-Saharan Africa countries which have been pervasively affected by insufficient economic growth, political instability, and poverty. In conclusion, this study will provide empirical evidence on whether further efforts in export diversification are warranted, and their potential to induce further economic.

5. Model Specification, Methodology and Data Sources

- The objective of the study is to examine the relationship between export diversification and economic growth from 2005 to 2015 for Ecowas states, test the hypothesis of a hump-shaped relationship between export diversification and economic growth and then compute the Critical concentration Index (CECI*) so as to check whether a hump-shaped relationship exists between export diversification and economic growth. A dynamic panel data estimate will be use for estimating parameters in our statiscal model. Firstly, a summary statistic table will be analyzed. Secondly, we will estimated the model, check the diagnostics and finally we will interpret our result.

5.1. Model Specification

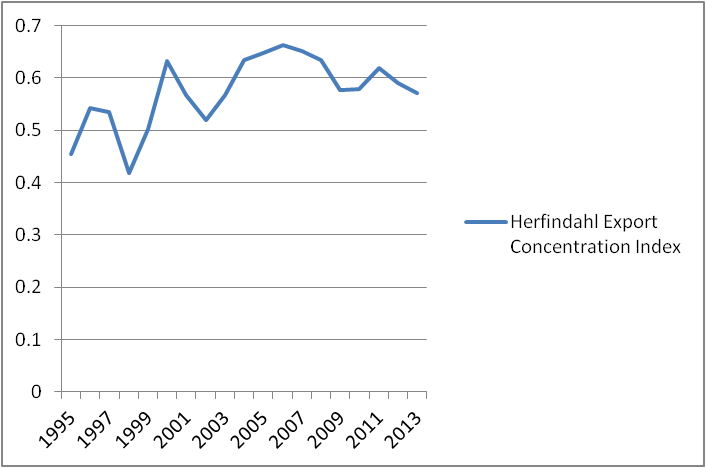

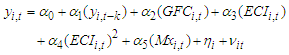

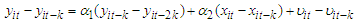

- The fifteen cross-country growth equation is written as follows:

| (1) |

is an unobserved country specific time-invariant effect. For instance, the impact of geography, the role of institutions do not change much over time but varies across countries.

is an unobserved country specific time-invariant effect. For instance, the impact of geography, the role of institutions do not change much over time but varies across countries.  is the random disturbance term that varies across both countries and years and is assumed to be uncorrelated over time.By inserting the components of the Xi,t in the equation (1) it can therefore be re-written as:

is the random disturbance term that varies across both countries and years and is assumed to be uncorrelated over time.By inserting the components of the Xi,t in the equation (1) it can therefore be re-written as: | (2) |

is the GDP of West Africa,

is the GDP of West Africa,  is the lagged GDP.

is the lagged GDP.  is Gross Fixed Capital Formation proxy as Capital Accumulation.

is Gross Fixed Capital Formation proxy as Capital Accumulation.  is the index of export concentration.

is the index of export concentration.  is a squared term of the index of concentration.

is a squared term of the index of concentration.  is share of manufactured products in total exports.In order to find the critical CECI*; point at which the real GDP in West Africa turn around occurs in relation to export concentration, we will derive by setting the partial derivative of real GDP with respect to the index of export concentration to zero from equation (2)Thus,

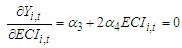

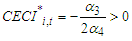

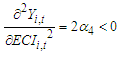

is share of manufactured products in total exports.In order to find the critical CECI*; point at which the real GDP in West Africa turn around occurs in relation to export concentration, we will derive by setting the partial derivative of real GDP with respect to the index of export concentration to zero from equation (2)Thus,  This gives

This gives  | (3) |

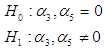

Equation (3) gives the Critical value of export concentration Index that will be computed if there is evidence of a hump-shaped relationship between export diversification and economic growth in West Africa. It is hypothesized as follows: The null hypothesis rejected the evidence that there is no linear relationship between Export diversification and economic growth and while the alternative hypothesis will accept the hump-shaped relationship between the export diversification and economic growth

Equation (3) gives the Critical value of export concentration Index that will be computed if there is evidence of a hump-shaped relationship between export diversification and economic growth in West Africa. It is hypothesized as follows: The null hypothesis rejected the evidence that there is no linear relationship between Export diversification and economic growth and while the alternative hypothesis will accept the hump-shaped relationship between the export diversification and economic growth Equation (2) will be subject to empirical scrutiny, and this model will be used test the diversification led growth hypothesis. It is hypothesized as follow:

Equation (2) will be subject to empirical scrutiny, and this model will be used test the diversification led growth hypothesis. It is hypothesized as follow: It is hypothesized that estimates

It is hypothesized that estimates  are different from zero and statistically significant, thus confirming the diversification led growth.

are different from zero and statistically significant, thus confirming the diversification led growth.5.2. Methodology

- Our equation (2) will be estimated by using the dynamic panel estimation method proposed Arellano and Bover (1995). We choose This method because it takes orthogonal deviations in the variables. It ensure the model to be properly identified and test the dynamic specification of the model.In fact we use the GMM method suggested by Arellano and Bover (1995) because it avoid the following shortcomings:Firstly, The problem of the endogeneity of the explanatoray variables.Secondly, the cross-section estimator will be inconsistent if the unobserved effect is assumed to be correlated with the explanatory variables.

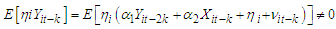

Using the Generalized Method of Moment developed Arellano and Bond (1991) and Arellano and Bover (1995), it will overcome the gaps in the OLS estimator in conventional cross –sectional regressions.The Estimation process involves taking first differences of the regression equation which removes the unobserved country –specific time invariant effects. As a result, there will be no omitted varibles bias across time-invariant factors.The following equation with lagged endogenous variable is estimated:

Using the Generalized Method of Moment developed Arellano and Bond (1991) and Arellano and Bover (1995), it will overcome the gaps in the OLS estimator in conventional cross –sectional regressions.The Estimation process involves taking first differences of the regression equation which removes the unobserved country –specific time invariant effects. As a result, there will be no omitted varibles bias across time-invariant factors.The following equation with lagged endogenous variable is estimated: | (4) |

and second, lagged values of the dependent variables and other explanatory variables in level are valid instruments.

and second, lagged values of the dependent variables and other explanatory variables in level are valid instruments.5.3. Source and Data

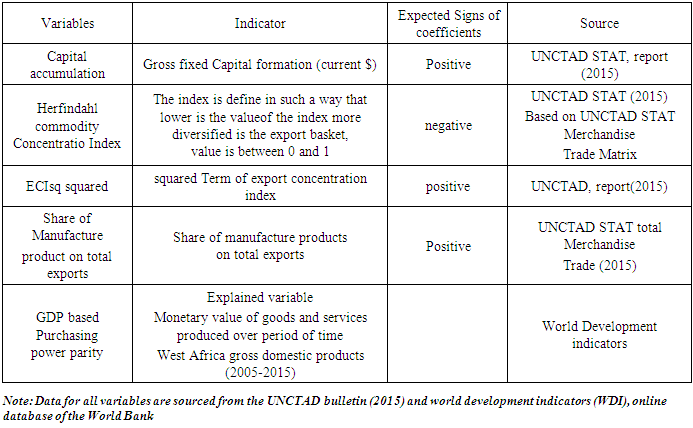

- The selected area for our research will cover the 15 West African countries, which is consisted of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Cote D’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra-Leone and Togo. Table. 1 below provides a summary of the explanatory variables, their proxies and the expected sign of their coefficient in relation with to GDP.

|

6. Estimation Result

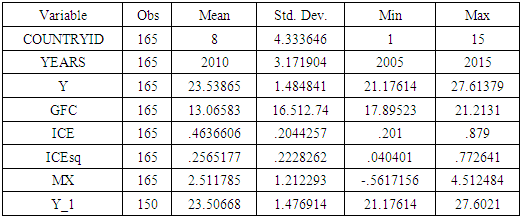

- Over the period 2005-2015, the mean of the dependent variable GDP shows an average of growth of 23.54 points with a standard deviation of 1.48 points.The range of GDP is between 21.18 and 27.61 points. This range gives an indication of the income disparity gap among countries in West Africa region. Where Zambia possess a low income comparing with Nigeria with high income.The average capital accumulation rate is 13.06 points with a standard deviation of 16.51 points. The range of (GFC) is between 17.89 and 21.21 points. This range is due to the narrow existing knowledge disparity gap between ECOWAS states for the creation of new knowledge.

|

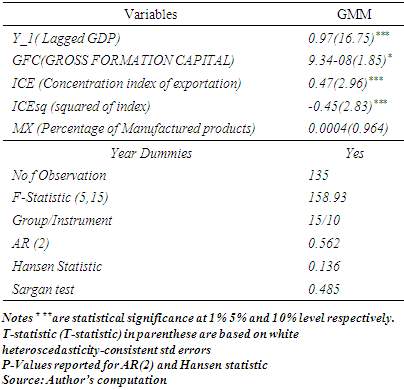

6.1. Dynamic PAnel Data Estimated Results

|

7. Discussion of Empirical Findings

- The dynamic panel estimation result for the 15 West African States (ECOWAS) showed on table 1 above. All parameters are greater than 0.05. This is good and show a significant value of the parameters. The difference in sargan tests of instruments subsets also are exogenous.Regarding the lagged GDP, the t-statistic is greater than 2 and the P-value =0.00. This implies that the previous valued impact positively the current GDP. Regarding gross capital formation as first explanatory variables, the t-statistic is 1.85 less than 2 and P-value =0.085. This implies that this variable is significant only at 10% but the coefficient is positive as expected in the study. As main variable, the concentration of export index has been significant at 1% 5% and 10% as P-value =0.006 and T-statistics=2.96 however the coefficient expected to be negative has been positive. This implies that export diversification affect economic growth in West Africa. Regard the Squared term, the variable is also significant at 1% 5% and 10% as P-value =0.007 less than 0.01 However the coefficient expected to be positive has been negative. This implies there is a non-linear relation between export diversification and economic growth for Ecowas states. This means Export diversification impact positively in certain level and beyond that level the trend is reversed so that export specialization leads to growth.The critical value of concentration index,

Regard the share of manufactured product on export volume, it does not influence economic growth in West Africa because the T-statistic=0.964 is less than 2. Hence the coefficient is insignificant.

Regard the share of manufactured product on export volume, it does not influence economic growth in West Africa because the T-statistic=0.964 is less than 2. Hence the coefficient is insignificant.8. Findings Implication

- The growth performance of West Africa countries has been an issue of concern to individuals, policy makers, organizations and searchers overs the 60 years passed. Searchers showed that developing countries that diversified their exports such as East and southeast Asia have been able to achieve higher growth (Yokoyama and Alema, 2009).Others recent studies Like Pineres and Ferrantino (2012) found associations between episodes of export diversification and rapid economic growth for the last 45 years in Latin America countries. Though the theoretical and empirical literature largely points to a positive relationship between export diversification and growth, there exist regional data suggesting that some countries gain from export concentration while others benefit from export diversification. This mixed evidence was introduced into literature by Imbs and Wacziarg (2003) who provided a theoretical and empirical proof of a U-shaped relationship between export concentration and economic growth.Imbs et al (2003) showed that countries first diversify by spreading economic activity more equally across sectors. But, there exists a point in the development process at which they start specializing again.Our study is to assess the effect of export diversification on economic growth in ECOWAS countries and also test the hypothesis of hump-shaped relationship between export diversification and economic growth as well as compute the critical value of concentration index given that non- linear relationship exists.This Time, we used Generalized Moments Method analysis and found that the link between export diversification and economic growth is non-linear, due to the t-statistic of the square term of export concentration, which has been integrated in our model test the non-linearity. T-statistic is significant and the coefficient is negative. This implies export diversification effect on economic growth is non linear. It exist a critical value 0.52, which level income falls with export diversification. In that level Ecowas countries should prone with specialization.Regarding the share of manufacturing products on export volume, our studies found an insignificant t-stastsitic. This means Ecowas countries should invest in more infrastructure, education area and industry sectors, in order to be able to manufacturer products and export in world market. However although Gross capital accumulation affect economic growth positively, it is weak as show on the table 1 above. One increase of Gross capital accumulation affect only at 9.10-8 point. Its impact is weak due the poorest infrastructure technology equipment investment In West Africa.

9. Conclusions

- When we see the export concentration index turn around 0.52 in average, this means export is highly concentrated. This invokes since independences, things have not changed much and the continent except South Africa still has with industry which cannot increase the added value of trade and therefore cannot boost the economy; the societal welfare continue to worsen and we observe a brain drain towards Europe. The growth performance of ECOWAS states remains a serious issue of concern to individuals, governments, organizations and researchers over the last two decades. While on the other side of the sea trade has acted as an engine of growth for the newly industrializing countries of Southeast Asia, Such as South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Their dynamic gains from trade arise from the effects of trade diversification and also on the level of investment, technical knowledge in their country. In sum it is time for the new generation and new policy makers of Africa to focus on Asia, particularly china. Not to copy its economy reform success but set up an economy reform adaptable to our African context by considering our culture and manner of living. The adoption of Structure Adjustment Program initiated by the World Bank and IMF early in the 1980s under the umbrella of the Washington Consensus to reverse the worsening economic trends of countries in the region did not give satisfaction. Hence a copy of western or Asia economy reform model could not suit for African countries. A model drawn only from their experience and adopted to our context can help SSA countries to avoid instability of commodity prices, which is inevitably leads to balance of payments problems and inability to steadily finance development expenditures.

Appendix

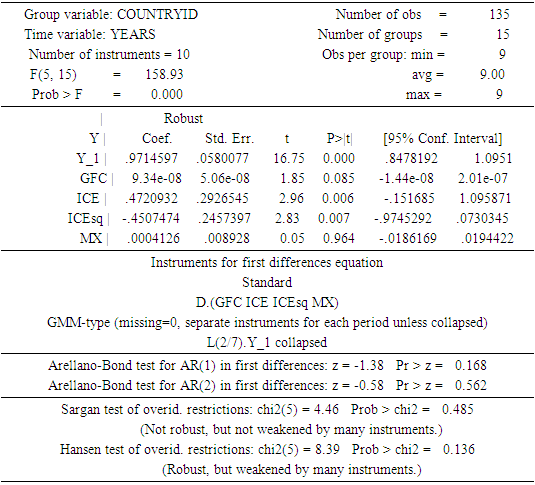

- xtabond 2 Y Y_1 GFC ICE ICEsq MX, gmm (Y_1,lag (2 7) collapse) iv (GFC ICE ICEsq MX) noleveleq nodiff small robustFavoring space over speed. To switch, type or click on mata: mata set matafavor speed, perm.

|

Note

- 1. CFA=colonies Françoise d’Afrique /1euro=655.957 FCFA, The introduction of the euro did not lead to any substantial changes as far as the arrangements governing the franc zone are concerned (Decision of the Council of the European Union of 23 November 1998 concerning exchange rate matters relating to the CFA franc and the Comorian franc (98/683/EC)). Following the 50 per cent devaluation of the CFA franc in 1994, the fixed parity between the CFA franc and the French franc had become 1,000 CFA francs = 10 French francs.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML