-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2020; 10(6): 425-432

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20201006.12

Received: Sep. 1, 2020; Accepted: Sep. 29, 2020; Published: Oct. 8, 2020

Retaining a Concrete (Middle Class) in Post COVID-19 Era

1International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain

2University of Bahrain & International Institute of Inspiration Economy

Correspondence to: Mohamed Buheji, International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, led to unprecedented challenges to both the lower and middle class that shacked their average income and created disruption in the efforts of eliminating absolute poverty in almost all the countries of the world. An increasing proportion of the world population is under threat of not having a majority of stable or what could be called a (concrete) middle class. This means many communities might not find a way out of the vulnerability condition or the risk of being poorer, and could suffer the consequences of unstable socio-economic spillovers of the pandemic. In this paper, we review the status of the lower middle class and the requirements for a (concrete) middle class and see the types of capacity needed to ensure more communities prosperity. A framework is proposed for ensuring a more resilient middle class that would manage to stay away from the trap of poverty. This paper carries important implications for the future of communities and countries which are discussed in the conclusion of this study.

Keywords: Middle Class, Concrete Middle Class, Lower Middle Class, Poor Class, Economic Development, Poverty, COVID-19 pandemic spillovers, Socio-economic status

Cite this paper: Mohamed Buheji, Dunya Ahmed, Retaining a Concrete (Middle Class) in Post COVID-19 Era, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 10 No. 6, 2020, pp. 425-432. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201006.12.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The emergence of COVID-19 and its related spillovers brought with it a dramatic consequence that could cause a threat for a new type of poverty, or a source of vulnerability to many countries and communities around the world. Much of the middle class, or lower middle class lost their businesses, or became very fragile with the persistence of the spread of the virus and its related effect on both live and livelihood, Buheji and Ahmed (2020a). With the sudden halt of many types in different sectors and industries that are related to the dynamics of economy, and the stability of the socio-economy of lower- and concrete-middle class, this paper explores the untapped solutions of these largest and most important classes for any country which are the fundamentals for any community stability. CGD (2014); Acemoglu and Robinson (2013); AfDB (2011).The unprecedented challenges that are brought by the COVID-19 formed a new demand for the middle class, and shacked the definition of social class as we used to know it, Buheji and Ahmed (2020a). As we enter the eighth month since the declaration of the pandemic by WHO in early 2020, it is now clear that for countries to come back to their full potential of a stable socio-economic environment, they need to create both a ‘resilient-’ and a ‘persistent-‘ communities that can be mainly formed from the majority of the social class. Previous studies advise that the more there is a variety of middle of class that support, or supply the demand of the society the more a well-established quality of life can be realised, OECD (2019), Lopez-Calva et al. (2012). Therefore, in this paper we shall review all the type of the challenges brought by the COVID-19 pandemic on two levels of the middle class, one is the known lower-middle class, or which statistically labelled as the lower class. This class represents the category of people who are just above the defined poverty line of the country. The second level of the middle class is what we call the ‘concrete-middle class’. This is the class who are calculated as the exact middle class between the poor and the rich. It is the class that have all the privileges of the minimum guaranteed ‘quality of life’ services, while also having almost a stable source(s) of income.The authors first go through the definitions of the middle class, including the lower middle class. The importance of the middle class towards a stable and resilient economy and as a game-changer is emphasised. The changes in the distribution of income and strength of the middle class the essential for the continuity of their services are also reviewed. The characteristics of a stable and concrete-middle class, especially those that emerged up during the millennium and emerging developing countries, are discussed. Reviewing the literature brings more realisation of the lower middle class and helps codifies the vulnerability of this class in developing countries. The literature exploits the facts of the shrinking middle class for the years after 2020. Based on the literature review and the discussion, a framework is proposed.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of Middle Class

- The middle class can be defined as those people or community who are not poor when judged by the median poverty line of their country’s standards. It is the class that represents the quality of life and adjusts the social classification of any country while broadly reflecting the ability of the nation to bring a well-balanced life, OECD (2011). Being a middle class means one or his/her family would enjoy stable or semi-stable housing, healthcare, educational services and variety of life and livelihood opportunities. This class usually targets with the ambition that their children or their next-generation reach a higher level than they could reach in all areas of development, including education, jobs, opportunities, etc. CGD (2014); Easterly (2001).In the coming sections, we shall elaborate on the levels of the middle class, where there are mainly three levels: lower-, concrete-, and high-middle class.

2.2. Importance of Middle Class to a Stable and Resilient Economy

2.2.1. Middle Class as a Game-Changer

- The growth in the middle class in any country plays a vital role in its economic and socio-economic plans. Besides its impact on the capacity of the community development, a stable middle class is considered to be the main game-changer in both life and livelihood issues in any community. Birdsall (2010).As a game-changer, many countries claim the rise of their middle-income class, especially in the first decade of the 21st century. In developed countries, these game-changers would have earnings of US$10-20 per day. But, in reality, is this only for the concrete upper-middle class. To be a real game-changer, we need to account for more stable income for the majority of the middle class and especially the lower middle class. Besides, game-changing cannot depend on materialistic capital; it needs more other types of wealth. Frank (2020); Birdsa (2015).

2.2.2. Middle Class and Their Role in the Economy

- Middle-class represents the consumerism phenomena in the capital economy where the lifestyle pervasiveness brings in demands or the eagerness for striving towards a specific lifestyle status. In any community, the social designation of middle class been always measured in terms of income or consumption levels. Frank (2020); OECD (2011).The lifestyle of middle class helps governments and community planners to foresight the two extreme ends of the income distribution and the type of quality of life expected, Buheji, (2019a). The rapid consumption of the middle class is creating an increasing inequality in income distribution. The sustained escalation of this consumption created more profound inequality that is having a negative impact on all the levels of the middle class. This inequality of wealth distribution became more of complex problems with the advent of COVID-19 pandemic, where the majority of lower middle class suffer. OECD (2019), OECD (2011), Ornstein (2007). The call-in this paper for a global middle class, represents both the concrete- and the lower-middle class, which would encapsulate the plus three billion population by 2020. The bulk of this growth as forecasted come from Asia. Pre-COVID-19 it was estimated that by 2030 Asia would have 66% of the global middle-class population. Buheji (2020); Pressman (2016), Ali and Dadush (2012), Kanbur and Spence (2010).

2.2.3. Distribution of Income and Strength of Middle Class

- With the existing size of the middle class and the distribution of income, we can estimate and foresight the current size and future trajectory of this class for each country, Buheji (2019a). About half of this middle-class live in developed economies, but this percentage is changing with the speed of growth of the middle class in countries as India, China, Brazil and South East Asia. Besides Africa is witnessing a fast development in this class too. Buheji and Ahmed (2019); Easterly (2001).The UN SDG targeted that by 2030 the world would evolve from being mostly poor to mostly middle class. However, the continuous financial and economic shocks, besides the health crisis of COVID-19 would delay this ambition at least two decades more. Kanbur and Spence (2010).Given the broad range of expenditures that fall within the middle-class definition, some countries have more affluent middle classes than others. Therefore, while the middle class in Europe and North America cover 54 per cent of the global total in terms of the number of people, they account for 64 per cent of total spending by the world’s middle class, Easterly (2001). While in 2009, Asian, middle class accounts for only 23 per cent of the expenditures of the global middle class; they were expected to account for 59 per cent by 2030, before the pandemic. Buheji (2020); Ali and Dadush (2012).

2.2.4. Continuity of Middle-Class Services

- Datta and Deb (2020) reported about the interruption in middle class services due to the pandemic. Specifically the concrete-middle class, always carry the burden of the economic or socio-economic crisis. Thus, having more concrete-middle class would help to maintain the wealth and income within the community. With the pandemic of COVID-19 touched all part of life, many livelihoods, social protection, and welfare related services came to a halt. The continuity of the middle-class services came to a total stop. Many middle-class families had to accept the minimal services provided especially in developing countries. This affected further the fragility of the lower-middle class in this part of the world. Buheji et al. (2020); OECD (2011).

2.3. Characteristics of Concrete-Middle Class

2.3.1. The Changes in the Concrete-Middle Class

- In order to ensure that an individual or his/her family would be from the concrete-middle class, their capacity should be tested to withstand the current world emergency crisis of COVID-19 pandemic and its coming spillovers. Buheji et al. (2020).Studies confirm that concrete-middle class was rapidly expanding in emerging and developing countries, while it was shrinking in rich countries, Kharas (2010). With the spread of COVID-19 many people and especially the poor and the middle class, the pinch of the existing socio-economic challenges became more painful and irritating. This led series of protests and riots by a majority that mostly comes from the different levels of the middle class. This class and specifically the lower middle class went to the streets after realising the impact of the lockdown and what deterioration it has on their daily life. Buheji and Ahmed (2019), Birdsall (2010).

2.3.2. The Emerging Middle Class in Developing Countries

- The emergence of the middle class is far away from all those living in households with specific daily per capita income, Birdsall (2010). The combination of household survey data with growth projections for 145 countries, materialistically shows that Asia share by 2020 could double. Buheji (2020); Ali and Dadush (2012).Some researchers’ foresight that emerging countries like India and China soon have both lower- and concrete-middle class that drive consumption and demands for products and services, Buheji (2019a); Meyer and Birdsall (2012). The mass middle class would lead to a transformation in the priority of designs styles from the West to the East, and for the first time from 300 hundred years. In Africa, the middle class growth already contributed to an increase in domestic consumption in household electronic items, mobile phones, motors and cars. For example, the possession of cars and motorcycles in Ghana has increased by 81% since 2006. Kharas et al. (2010); Kharas (2017).

2.3.3. The Characteristics of the Millennium Middle Class

- From 2001 to 2011, nearly 700 million entered the middle class and stepped out of poverty, but most were very fragile. This rapid transformation from poverty to lower- or concrete-middle class started from the first decade of this century and could be clearly seen in the emerging economy countries, Buheji (2019a). The middle class approximately doubled in size and income, but many remained in the level of lower middle income. Summers and Balls (2015), Dabla-Norris et al. (2015). Before COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of the world’s population (56%) continued to live a low-income existence, compared with just 13% that could be considered middle income by a global standard, according to a new Pew Research Center (2020) report. Buheji et al. (2020).The millennium global middle class can be seen clearly through the remarkable progress of China. China managed in just three decades (1978-2011) to increase its middle class through a unique economic reforms program; however, the majority counted at just about US$10 per day. This development towards lower middle class also happened in Eastern Europe, South America and Mexico. Bennett et al. (2020); Loayza et al. (2012); Lopez-Calva et al. (2012); Easterly (2001).

2.3.4. Middle-Class Engagement in Public Services

- The stability of a well-established middle class would increase their appreciation to public quality services, and their acceptance for more expenses set by the government. This rapid growth in both lower- and concrete-middle class increase the demand for better education, healthcare, pension, housing, etc. The innovation in household services and products made many these families to tap into their wealth which led to a decline in their saving rates. Many lower- middle class could not build enough savings now and became more vulnerable than ever for receiving or demanding minimal public services. Pressman (2016), Kharas (2010), Ornstein (2007). Middle class need to be stable to build what is called the ‘cultural capital’ (education, networks, skills and resources) of the community where better schooling, health services and neighbourhood planning could be experienced, OECD (2011), Ornstein (2007). In order to increase the average income and the fall in levels of absolute poverty, we need to increase the concrete middle class engagement with public services. This requires a population that is neither rich nor poor by national standards but finds itself in the middle of the income distribution. Sumner et al. (2020), Pezzini (2012).

2.4. Realising the Lower Middle Class

2.4.1. Codifying the Lower Middle Class

- The low middle class are a class that is with a modest income range who are barely or just overcome the experience of poverty. This class are considered today, especially after the efforts of the UN-SDG’s to be the class with the highest number of people. Reaching a concrete middle-income status is still beyond the grasp of many these people who still are striving to eliminate the sudden threats of poverty. They still represent the majority of the world’s population. Sumner et al. (2020), Buheji (2019b).The population of low income, or those who live on US$2-10 (per day) can reach 56% of the total global population. Hence, if we study the China’s progress from 2001 to 2011 in developing the life of a total population of 1.3 billion individual, the majority of those left poverty might be labelled as lower-middle-income.

2.4.2. Vulnerability of Middle Class in Developing Countries

- Frank (2007) emphasised that income inequality harms the stability of the middle class. It is estimated that more than 1.2 billion people joined the middle class in the developing countries since 1990, four-fifths of these came from Asia, and a half from China, OECD (2019). Most of the new entrants remained fairly close to poverty, with incomes now bunched up just above $2 a day. Sumner et al. (2020), Lopez-Calva et al. (2011).Thus, the vulnerability of the developing countries middle class is very high. Most these people could be classified as a lower middle class where one in six people live on between $2 and $3 per day. It is such type of middle classes that are also slowing the economic growth in their countries or communities. Birdsall (2010).To ensure sustainable, resilient economy, Buheji (2017) seen that it should be measured on the extent to which the middle class can get stability as a result of the sustained and sufficient shared economic growth over 15–25 years. Lopez-Calva et al. (2011).

2.4.3. The Shrinking of Middle Class for Years after 2020

- Given that a concrete middle class need to gain fixed US$10 middle-income per day as a requirement, it is highly expected that more 30 per cent of this class would fail to meet this requirement after the advent of COVID-19 pandemic, Buheji et al. (2020). Actually, the majority of the lower middle class would have a very challenging time not to fail under the poverty line. The shrink in the percentage of the population of middle income in most of the developed and developing countries, besides the emerging economies, would lead to the destruction of UN-SDGs efforts that focused for a decade towards the elimination of poverty, Davis and Huston (1992). This shirking would prevent the shifts of many proportions of the poor population from rising to the concrete middle class in the foreseen future. Buheji (2019b); Kharas (2010); Birdsall (2010).

2.5. Maintaining a Middle Class that would Help Overcome the Threat of Poverty

- Lots of studies and efforts have been made to eliminate or end poverty in the last three decades by all the global partners; however, it is proven to be not an easy goal especially in the presence of unstable world environment. Historically, there have been many efforts designed in a way to eliminate poverty; Sumner et al. (2020). For example, lots of legislations tried centuries ago, starting by the Elizabethan Poor Law in 1601, which was an act for the relief of the poor. However, all these efforts never managed to solve the source of the problem, where many poor people and their communities cannot make a breakthrough transformation towards a concrete middle class. Most of the models actual. Buheji and Ahmed (2019).

3. Methodology

- Based on the literature review and its synthesis, a proposed framework is set to re-design a new normal concrete middle class with a capacity and a competency that would meet the demands for the coming challenges similar to the COVID-19 pandemic. The framework goes beyond the physical comfort of the middle class and targets their overall socio-economic stability. The framework focuses on pulling the lower-middle class towards the concrete-middle class using the Pareto concept. The way the middle class are measured is discussed in detail in order to re-establish a new abundant mindset of what we call concrete-middle class. This is a class that would reduce the vulnerability and ensure the continuity of the middle class.Realising the work of Buheji and Buheji (2020), the matrix in framework links between the two dimensions. One dimension focus on the conditions of the new normal, the other explores the five-competencies that need to be reflected in the concrete-middle class of the community.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Problem with Current Classification of Middle Class

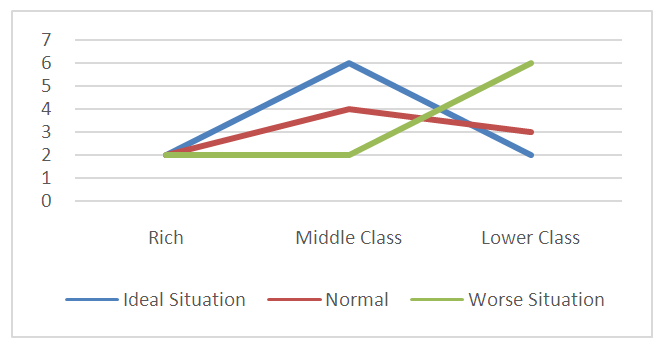

- Currently, any society is divided into five classes labelled as: the poor, the low income, the middle income, the upper-middle-income, and the high income. In order to reach a concrete stable middle income, which called a concrete middle class; the poor need to go through two thresholds. The first threshold is to have earnings of US$2, so that to move from the poverty class to the lower middle class. Then, in order to reach the concrete middle class, the individual has to earn US$10 daily. Therefore, the current definitions focus on the attainment of a financial income in order to reach or stay as a middle-income. Sometimes these monetary incomes are also described the purchasing power parities (PPPs).In order to maintain and retain a concrete middle class, the world needs more ‘capacity vs. demand’, ‘pull thinking’ approaches for this class. This means the support programs need to be eliminated or controlled, and replaced by more development program. Despite that some middle class were more able to move to upper-middle class, the ability of the lower class to move to concrete middle class stayed weak, even with the presence of education and technology-supported programs. Buheji (2019c), Pressman (2016), Ornstein (2007).The life and livelihood threats that COVID-19 pandemic brought to us, taught us that stability needs gauges much more than a monetary income, i.e. provision of indicators that ensure the establishment of wellbeing and the visualisation of the roles and goals of life. i.e. What is the use of gaining a middle-income threshold of above US$10 if we believe that we cannot maintain it, or cannot see how to optimise the outcome of it. Having an earning of five times of the poor with US$10 threshold, does not protect the low-income middle class from poverty in cases of disasters, or during life catastrophic challenges. Figure (1) illustrates the three different scenarios that the world would face after the COVID-19 pandemic. The first scenario is the ideal situation where the concrete middle class would be the majority. Then, the second and the third scenarios would the normal or the worse situation where the middle class would be higher, or similar to other classes. The ideal situation could be a target to create elimination of the possible return to poverty, by retaining more concrete middle class.

| Figure (1). Type of Scenarios of Middle Class |

4.2. Applying ‘Pareto Concept’ on Social Class

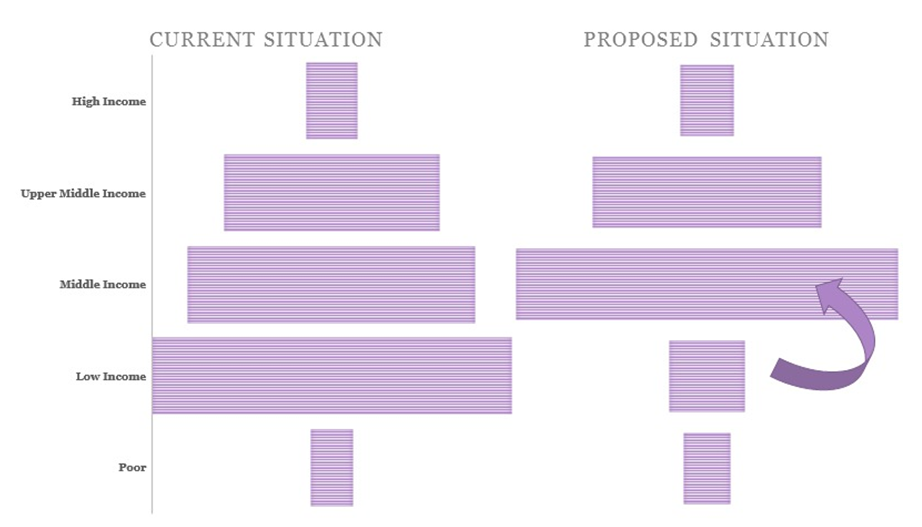

- Studying the status of the world achievement of elimination or alleviation of poverty shows that the growth in the low middle-income population only was dominated by the data collected for the purpose of showing prosperity in the emerging economies; especially China, India, Southeast Asia, Africa, South America and Eastern Europe. Majority of these data accounted to have eliminated poverty, but actually stayed in the lower-middle-class income category. Many of these countries middle class could not make their way to a concrete middle-class income. Kchhar (2015). Since we need to focus on the ‘effective few’, as per Pareto concept, and in among all the five classes, i.e. the lower middle class, we need to work on changing the economic formula that focuses on raising of the capacity rather than the supply. Pareto as a concept could help the planners see how to bring many people to the concrete middle class (at least 5-8 per cent of the population). Such an attempt is expected to bring down the poverty rate and improve the concrete middle-class income. In the meanwhile, the African countries experienced, almost all the movement from poverty to low-income status only. Only a few countries had much of an increase in the share of concrete middle-income earners. For example, while a country like Nigeria and Ethiopia, managed to eliminate more than 18% and 27% of its population from being poor, more than 17% and 26% of them stayed in the low-income class consequently. Only 1% of these two African emerging economies managed to move to the concrete middle class. Therefore, a framework is needed to help identify the challenges of the lower middle class with a focus on what conditions they could go through during global emergency status as in the COVID-19 pandemic, rather than just focusing on their standard of living, as most studies in literature did. This means, in order to mitigate the spillovers of COVID-19 pandemic, governments need to work in creating middle-income generations that could live, generate or have the standard of living with a new mindset which would eventually also ensure a living income of $10-20 a day/individual. Reaching such a standard of living would eliminate the struggle with income inequality and poverty. Buheji and Ahmed (2020b); Birdsall (2015), OECD (2019).Going back to Pareto principle, again, the ideal case is to have most the majority of the community at the concrete middle-income group and then much less at the top and the bottom of the society, as shown in Figure (2).

| Figure (2). Illustrates the Stratification of five classes where the Majority of the Community would be the Concrete Middle-Income group |

4.3. Why We Need to Redefine Middle-Class Measurement?

- As we all know, living on US$10 a day may not address the daily needs of the middle class of a U.S., or Germany citizen while it could be for example. Therefore, the new normal world needs more than ever today to unify a common and more practical way of defining what could be called concrete middle class. The more this definition is clear and is away from monetary definitions, the more we could create a resilient middle class that would not fall into poverty once a disaster or a crisis occurs. Buheji and Ahmed (2020b).Once the middle-class measurement actually redefined, the capacity to be self-motivated should help the middle class in creating social, economic and even political changes in both the short- and long-term. This class should have the capacity and the well to create economic equality and exploit opportunities essential for the existence and stability, Kchhar (2015). Thus, instead of focusing on what is the potential stimulus that may be provided to the middle class, governments more than ever need to focus on what would limit the concrete middle class from contributing to the socio-economic development. Birdsall (2015).

5. Proposed Framework

5.1. Redesigning the Characteristics of New Concrete Middle Class

- When analysing the changes in the world’s middle-income population at the start of the 21st century, and the purchasing power parities (PPPs) in 111 countries that account for 88% of the global population, we found that the majority are in the lower side of the middle class. This fact means that this class is not ready for another international disaster or emergencies similar to the pandemic of COVID-19, or similar coming challenges and mostly would be very vulnerable should such pandemic or conditions persist.As the world goes in the new normal, after the devastating pandemic of COVID-19, a concrete middle class with new characteristics is highly in demand. They are a class that would not be described as looking for quality of life, or with certain income, or living standards, but rather a class that is full of ‘givers’ than ‘takers’ and with clear life purposefulness.

5.2. Changes in Middle-Class Lifestyle in Post-COVID-19

- Today many middle classes find their goals within a speciality, or open their own startup, or strive with their business while working under the umbrella of social insurance which guarantees them a decent retirement and job security. Usually, the families of this class would play a major role in the dynamics of the local hospitality industry, the cycle of the local economy as they are capable of having paid vacations and afford to have leisure time. Access to public services is becoming a concern to families of many middle classes in the post-COVID-19 era. Going back to simple basic services with ease of accessibility is now more in demand, as it became a new normal trend. Kchhar (2015).

5.3. Re-establishing a New Abundant Mindset Middle Class

- The world needs to develop the type of middle class that would eliminate the accumulation of the lower middle and ease their penetration towards the concrete middle class. Being a critical socio-economic influencer, the middle class should be transformed from a scarcity growth mindset to more of a source of an abundant mindset middle class. Having such an abundant mindset driven middle class would help to establish a more stable middle class that could provide a concrete foundation for deeper socio-economic progress.

5.4. Competency of New Middle Class in Post-COVID-19

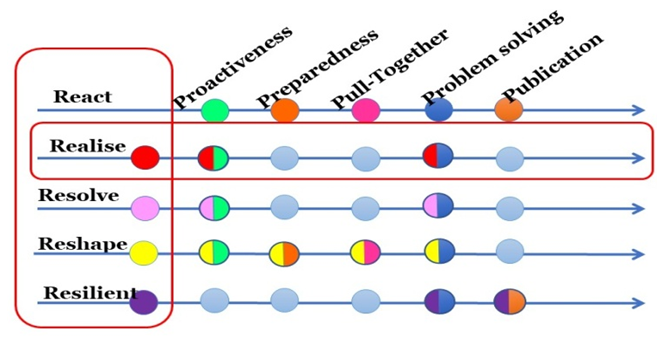

- In order to meet the disruptive, fuzzy and turbulent ‘new normal’ demands the new or concrete middle-class competency need to be redesigned to fit a two-dimensional framework. The framework proposed targets to absorb and compensate for the turbulent environment foresighted in the coming era. The first-dimension of the framework would focus on defining the demands of the new normal. This dimension would be the main pillar that would control the competency exploitation of the middle class. In contrast, the second dimension focuses on the type of essential concrete middle-class competencies required in the ‘new normal’. The two dimensions complement each other to create the necessary resilient matrix that would enhance the concrete middle-class elasticity and improve its tolerance to absorb and learn from the shocks and bounce back. Buheji and Buheji (2020).

| Figure (3). Illustrates the Two Dimensional Matrix of Competency Required for New Middle Class in Post-COVID-19 Environment (After the Work of Buheji & Buheji (2020)) |

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Vulnerability vs. Continuity of Social Mobility of Lower Middle Class

- Despite having incomes which are above international, or even national poverty lines, the lower-middle classes in many cases remain vulnerable. Their employment (many works in the informal sector), education (few have university degrees) and consumer behaviour do not coincide with perceptions of the concrete middle class that drives domestic consumption and growth while being resilient and stable. Governments are expected to foresight the type of vulnerabilities that could or might limit the social mobility of a stable and resilient middle class and thus ensure its continuity. For example, how to ensure the continuity of the middle-class social welfare system, or safety nets, or lifelong learning programs, or their engagement in civil society development. In the same time, the foresight should include protection of the most vulnerable segment of the middle class should sudden disasters, or crisis create instability to their employment opportunities, or quality of life services (as education, healthcare and social security), or create a threat to their life or livelihood. Therefore, one could consider that the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity, like a stress test, for testing the capacity needed for a concrete middle class that would have better chances for continuity and sustenance of its influence on social mobility programs. The rapid increasing susceptibility of emerging non-poor populations, but not well-established middle class, are increasing the vulnerability of much of the population that would be fragile to any sudden crisis or unprecedented emergencies as the COVID-19 pandemic. Such type of class would have precarious sources of income that raise their socio-economic instability and will not help towards establishing a sustainable development that leads to socio-economic progress.

6.2. Implications and Limitations

- This paper opens a new line of research that focuses on the elimination of all sources of vulnerability of the middle class, specifically the challenges of the lower middle class. The rising expectations towards the realised expansion of the middle class in developing countries need to overcome the stagnating living standards and the new trend of a shrinking middle class as per OECD (2019) latest report. The world need, as per the outcome of this paper, a more learning middle class. i.e. A concrete middle class that would exploit the opportunities of the new normal as per characteristics, similar to the proposed framework, to bring in a new concrete experience that comes from active experimentation, from the art of giving, not taking. These profound approaches would be only realised through being tested in the field, i.e. with the poor and the lower middle classes. The time now is the most suitable to have the gut to test such models before we see a world that would dip deep into poverty again. It is highly recommended that future researches focus on the drivers of change in the middle class in relevance to both scope and time, especially in the new normal. The basic human needs and desires for a stable middle class need to be understood and explored further. Due to the limitations of the scope of this research, the lower-middle-class human needs and the gap in the competencies missing were not exploited in this research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML