-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2020; 10(6): 352-359

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20201006.05

Received: July 26, 2020; Accepted: August 15, 2020; Published: August 29, 2020

External Openness, Human Capital, Unemployment and Economic Growth Case Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt

Rezine Okacha, Nezai Azzeddine, Kada Yazid

Faculty of Economic Sciences, Dr. Moulay Tahar University, Saida, Algeria

Correspondence to: Rezine Okacha, Faculty of Economic Sciences, Dr. Moulay Tahar University, Saida, Algeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Starting from the assumption that the training and experience of the workforce represents a form of (human) capital. An investment in this capital could affect the process of economic growth. Our study will examine this relationship in a sample of 04 countries (Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt) and during the period (1980-2020). The estimate is efficient for our model because; the coefficients associated with physical capital, the years of higher education are statistically significant, and are based on an essential point is that the years of study will have a positive impact on growth economic.

Keywords: External openness, Human capital, Unemployment, Economic growth

Cite this paper: Rezine Okacha, Nezai Azzeddine, Kada Yazid, External Openness, Human Capital, Unemployment and Economic Growth Case Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 10 No. 6, 2020, pp. 352-359. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201006.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- To understand why certain countries are developing rapidly while others remain in underdevelopment, many economists (Denison, 1962) have started from the observation that growth had been greater than what would have been implied by the progression of the two main economic factors of capital and labor. This unexplained growth has been attributed to a “residual” factor supposed to represent technical progress or the “quality of work” which will be reflected in the soot in the conception of “human capital”.Recent growth studies also assume that the training and experience of the workforce is a form of (human) capital. And investing in this capital (in the form of spending on learning and training, for example) could have a more permanent impact on the growth process.Our work is based on the hypothesis that the number of years in itself is less relevant than the nature of the training followed. In this perspective, we propose to examine the role of education and other variables such as trade openness or even physical capital and the rate of unemployment in economic growth.

2. Definition of Concepts

2.1. External Openness

- The external openness the designates both an attitude in matters of international economic relations policy and an evaluable fact. The best-known indicator is the openness rate. But it only concerns trade in goods. For a more complete overview of indicators and major trends in this area, see the notion of international trade. (webclass, 2019):• The foreign opening policy designates the desire to increase economic exchanges of all kinds and/or to reduce the obstacles to this multiplication. Free trade is the liberal form of this will;• The degree of external openness is a fact that we measure, particularly in trade (imports and exports of goods): see the definition of the openness rate. Other indicators of this type can also be used to assess the relative importance of cross-border capital flows, for example…

2.2. Human Capital

- The concept of "human capital" has been used frequently in economics for at least thirty years (eg Schultz, 1961; Becker, 1964); some trace it back to the work of Adam Smith in the 18th century. The concept strongly emphasizes the importance of the human factor in knowledge and skills-based economies. It is useful to distinguish between the different forms of “capital” used in economic activities - especially physical and human.Human capital, as defined by the OECD, human capital is the knowledge, skills, competences and other qualities of an individual that promote personal, social and economic well-being.“The knowledge, skills, competences and individual characteristics that facilitate the creation of personal, social and economic well-being,” OECD (2001, p18).Human capital can also be defined as a set of skills, knowledge, and qualifications possessed by each individual. These are, in part, innate inherited at birth (these are intellectual capacities transmitted genetically); for the other part, they are acquired throughout life. This acquisition is expensive but brings in a flow of future productive services. It is therefore an investment; therefore, the name of the capital is given to this stock of knowledge.

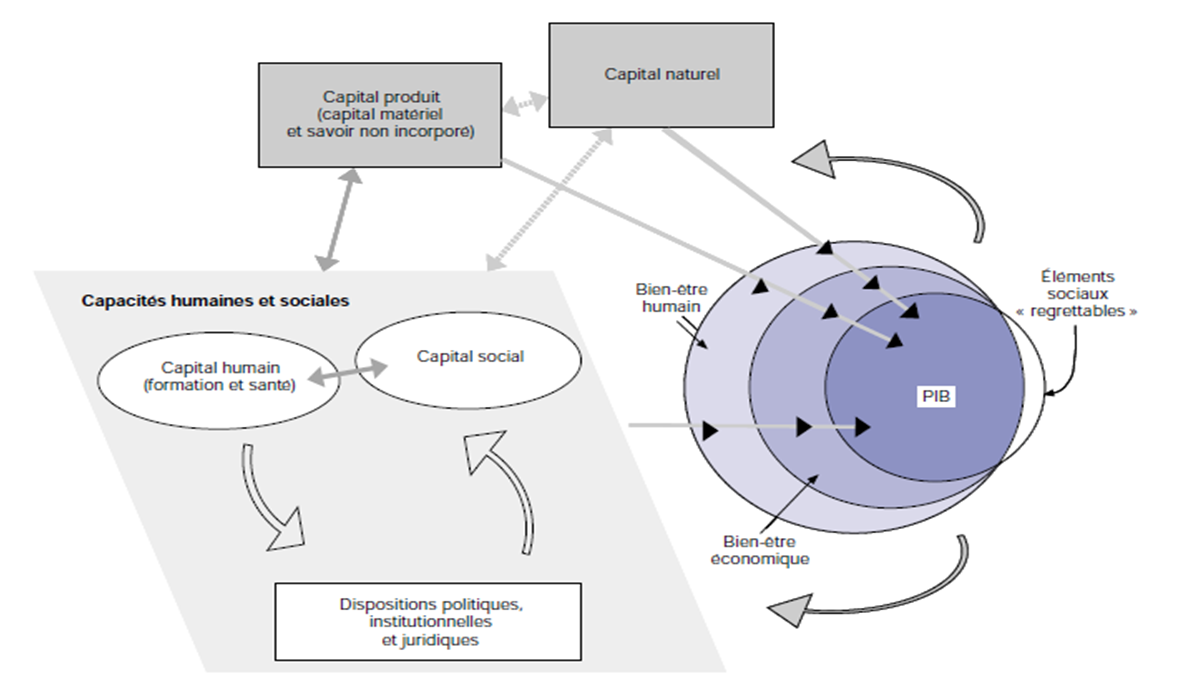

3. The Impact of Human Capital on Economic Well-being

- According to the OECD: human capital is reflected in the knowledge, skills, competences and individual characteristics that facilitate the creation of personal well-being. OECD (2001, p18) While “human capital” has often been defined as such and, assessed in relation to gain cognitive skills and specific knowledge, a more general notion of human capital, encompassing the characteristics of the individual, shows its crucial contribution too well-being. OECD (2001, p18) To meet all these needs, society must have different types of capital. A condition of sustainability is that the aggregate stock of its different types of capital does not decline over time. The capital includes OECD (2001, p20):1. Produced capitalIn other words man-made means of production, such as machines, tools and buildings, but also infrastructure that is not specifically linked to the production activity, intangible assets and financial assets allowing influence the current and future throughput of production;2. Natural capital In other words, the natural resources renewable, or not which enter the production process and serve to meet consumption needs, and environmental assets having a function of amenity or productive use and which are essential for the survival of the species;3. Human capitalIn other words the knowledge, skills, competences and individual characteristics which facilitate the creation of personal well-being. Thus defined, human capital includes training (structured or not) and health;4. Social capitalIn other words the networks of common norms values and beliefs that facilitate cooperation within and between groups.Different types of capital affect well-being through various channels and produce multiple spillovers. These benefits can be economic or non-economic, individual or collective. Training, for example, improves the earning prospects of individuals, but can also exert a favorable influence on non-economic variables (lowering the crime rate, in particular). Similarly, the spillovers can directly benefit owners (case of produced capital), to other members of their family (the level of education of parents, for example, influences that of children), to the community in which the individual lives (see the impact of social capital on petty crime) or to the whole of society (case of natural capital). OECD (2001).

| Figure (1). Different types of capital and individual well-being (Source: OECD (2001), Op.cit, P40) |

4. Training, Unemployment and Economic Growth

- The GEFOP conference organized by the French Development Agency (FAO), on November 12, 2007, places vocational training at the heart of development policies and emphasizes the role that vocational training can play, I quote: “The impact of vocational training is twofold (GEFOP, 2007):• On the one hand, it enables young people and adults to improve their professional skills, increase their chances of professional integration and be able to claim a decent income. It should therefore be an integral part of a strategy for sustainable poverty reduction and access to employment;• On the other hand, it allows companies, by improving the professional skills of employees, to increase the quality of their products and services, to improve their potential for innovation and competitiveness, and to move from a logic of survival to a logic of growth. It thus contributes to the revitalization of the national economies of developing countries”.Unemployment is an enormous problem for countries in the Middle East and North Africa; because their population has quadrupled since 1950 but unfortunately employment has not grown at the same rate (Gardner, 2003).Youth unemployment in the Maghreb is three times higher than among adults. The African Development Bank (AfDB) thus deplores that “while the youth unemployment rate at the global level was 12% in 2008, it was 24% in Algeria, 18% in Morocco and reached the alarming rate of 31% in Tunisia”. Figures which, however, “underestimate the extent of the problem since the rate of participation of young people in the world of employment is less than 50% in all three countries”. The AFDB also emphasizes the seriousness of “youth underemployment”. Young “poor workers” are legion in the Maghreb: in North Africa, more than a third of young people with a job still live with their families with a family income of fewer than 2 dollars per day per member of the family. (HReview, 2012).Few "decent" high value-added jobs are created in the Maghreb countries to absorb skilled labor. As a result, the returns to education and labor productivity are low. " The major cause, according to the ADB, would be the far too important place occupied by an informal sector which represents between 43 and 50% of total non-agricultural employment in the Maghreb countries, which would be linked in particular to "high costs of hiring”, to “the rigidity of labor market regulations and the slow progress towards the establishment of fully open economies”. First victims: young women and young people living in rural areas. (HReview, 2012).In these countries the labor market is underdeveloped, their education systems suffer from structural deficiencies and appear unsuited to the socio-cultural developments of these countries (Duret, 2005). In addition, higher education is characterized by a massification in general sections, which does not correspond to the expectations of the labor market. A gap has grown between the skills acquired and the needs of the labor market. The education system sorely lacks technical vocational training at the university level (Nicolas et al., 2009).

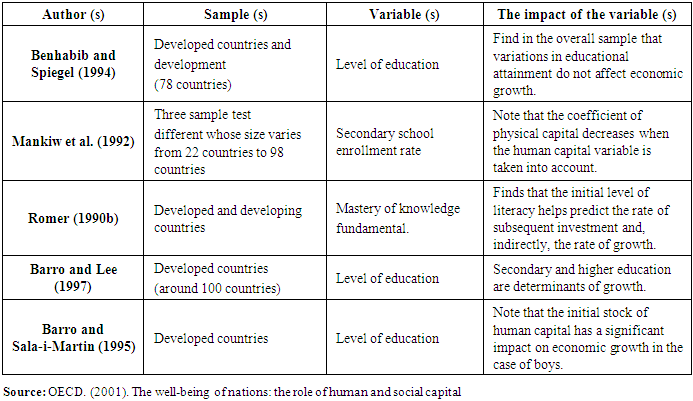

5. Previous Studies

6. The Empirical Study

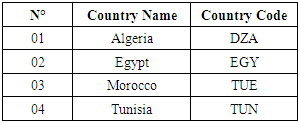

- In this study, we wanted to test the impact of public spending on education and vocational training on unemployment reduction and economic growth. The unavailability of data on vocational training forces us to study only the influence of other variables, namely: investment in fixed capital, higher education, on economic growth estimated by real GDP per capita. The selected countries suffer from high unemployment and low economic growth (Gardner, 2003).

|

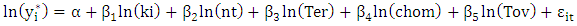

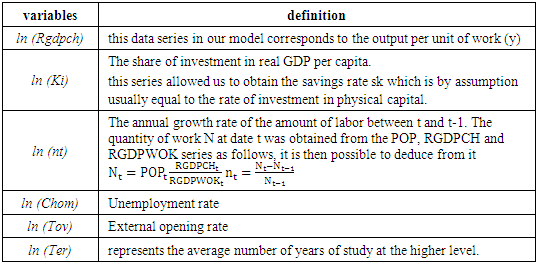

6.1. The Solow Model with Human Capital

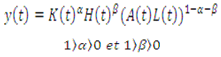

- This work is inspired by the neoclassical growth model developed by Islam (1995) which makes it possible to benefit from the advantages of panel analysis, one of which is the consideration of both temporal and individual effects. The model of Islam (1995) is essentially a specification of the model of Mankiw et al (1992) but on panel data. Mankiw et al (1992) used the foundations of Solow's (1956) model, in which they incorporated the concept of human capital. The production function is of the Cobb type-Douglas.

K: represents physical capital, H: human capital, L: work and, A is technical progress.

K: represents physical capital, H: human capital, L: work and, A is technical progress.6.2. Presentation of the Model

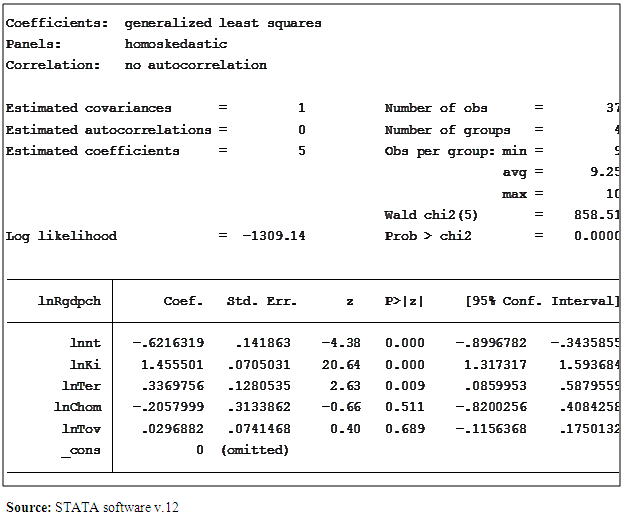

6.3. Estimation with (FGLS)

- Finally, with the presence of heteroskedasticities, estimators of (GLS) are then used with the necessary corrections.

|

6.4. The contribution of variables

- - Ki: 1.45 with significance (0.000)- nt: -0.62 with significance (0.000)- Ter: 0.33 with significance (0.009)- Chom: -0.20 with significance (0.511)- Tov: 0.029 with significance (0.689)(Note: the t-Student are in parentheses)The contribution of higher education and investment in real GDP per capita is very significant, this relationship is positive; that of openness rates is also insignificant. On the other hand, we detect a negative and insignificant relationship between unemployment and real GDP per capita. For the rest of the variables, i.e. those of the annual growth rate of the amount of labor (nt) are not significant. These results confirm the idea supported by Nelson and Phelps (1966), that productivity growth rates are positively correlated with the number of individuals who have completed higher education, as well as the work carried out by Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1995) who find that the number of students in higher education has a significant effect on the rate of productivity growth.This study also confirms the results of Morris (1982) and Lau (1982), which state that in developing countries the contribution of investment in fixed capital to economic growth is better when it is merged with an investment in human capital (Logossah, 1994). Although the influence of the unemployment rate is not in the same direction as the majority of the literature review, namely that it has an insignificant impact on real GDP.Our results concerning the role of external openness in economic growth are in contradiction with the review of the literature, which is explained by the fact that the countries taken into account in our study are mostly closed countries. Indeed, the study by Berthélemy et al (1997) indicates that the contribution of education to economic growth depends on the external openness rate of each country.

7. Conclusions

- First of all, the use of econometric panel data techniques made it possible to clarify and qualify our research problem. Regarding our results, we can first admit that the human capital growth relationship is well demonstrated within our sample and thus these results can be summarized in three essential points:• Solow's predictions about the negative attribution of population growth to growth are proven, and thus Solow's model allowed us to explain the data in our sample well. • The results confirm the idea proposed by Nelson and Phelps, Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1994), Barro and Lee (1997) that higher education is a determinant of economic growth. We note in our model that the coefficient of the higher years increases (by 33%), but that it always becomes significant, this result demonstrates the role that education plays on the relation human capital growth.• For the physical factors (public infrastructure and physical investments) are essential for the economic and social development of the countries in our sample and that they are priorities for the growth of these countries.According to the report prepared by Paul Dyer, World Bank for the Maghreb Round Table (Dyer, 2018), the Maghreb countries are grappling with the challenge of job creation between 2000 and 2020, and the growth of the active population in these countries will have been on average nearly 2.4% per year. This means that almost 16 million more jobs will have to be created between 2000 and 2020 for new entrants to the market. Given the unemployment rate estimated at 20.4% in the Maghreb, the countries of this region will have to create some 22 million jobs over the next two decades to occupy both the unemployed and new entrants to the market. This figure corresponds to the current level of employment in the Maghreb.Finally, the econometric estimates do not take into account any problems of simultaneity of the effects of the variables. While investment and education of course affect the level of income, the level of income must also influence the modes of accumulation of physical and human capital. The main limitation of this study lies in the quality and reliability of the data used. Because the analysis of the data revealed many aberrations that we tried to correct by eliminating either the country concerned or the variable concerned.

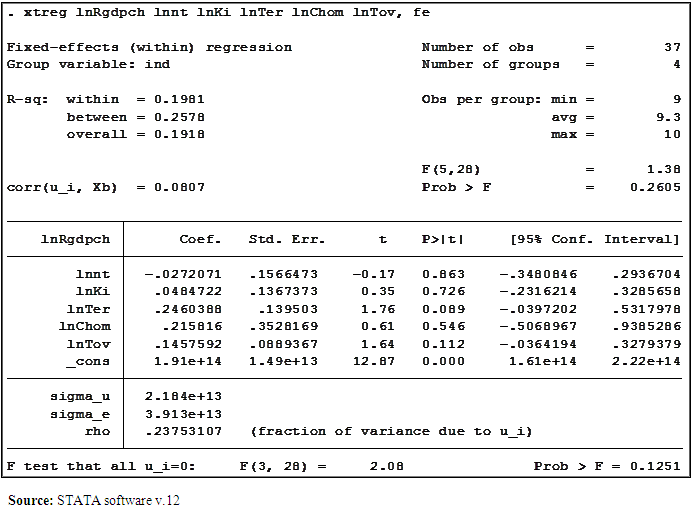

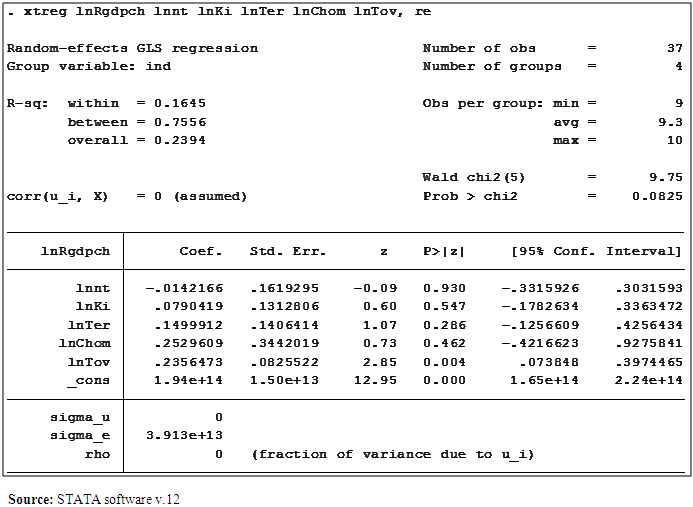

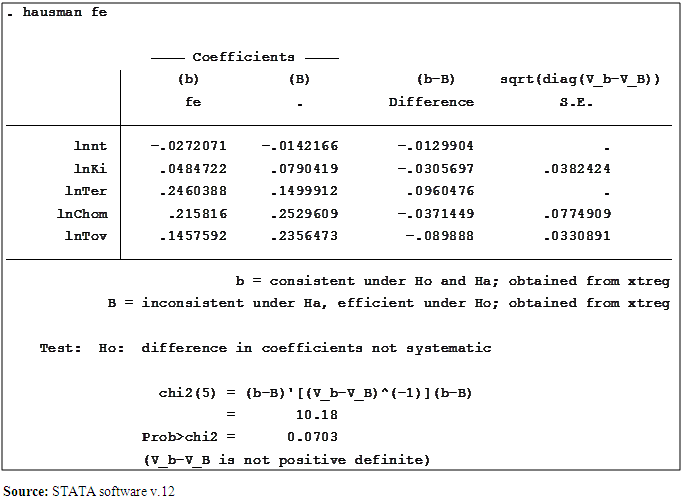

Appendices

- 1. Estimation of the fixed effects model

|

|

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML