-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2020; 10(6): 339-351

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20201006.04

Received: July 14, 2020; Accepted: August 16, 2020; Published: August 29, 2020

Monetary Policy and the Real Sector: A Structural VAR Approach for Nigeria

Adeniyi Foluso

The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants of Nigeria, Mulliner Towers, 39, 5th Floor, Alfred Rewane Rd, Ikoyi, Lagos

Correspondence to: Adeniyi Foluso, The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants of Nigeria, Mulliner Towers, 39, 5th Floor, Alfred Rewane Rd, Ikoyi, Lagos.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study attempt to investigate the effect of monetary policy on the real sector, by employing the structural vector autoregressive (SVAR) framework. It used a set of policy and non-policy macroeconomic variables based on monthly data spanning the period 2006 and 2019. The empirical results based on structural impulse response functions reveal that MPR as a policy tool provides significant results as it is effective in stabilizing price levels, increasing output marginally, and improving the nominal exchange rate conditions. Despite the innovations in the policy rate in the period covered, shocks to the nominal exchange rate have been a major challenge, it affects domestic economic activity complicating the effort of the monetary authority. Given the importance of international trade and investment in the process of economic growth, this study recommends a stern exchange rate policy action that will have good implications for output growth and complement monetary policy actions in Nigeria.

Keywords: Monetary Policy, Real Sector, Structural VAR Models

Cite this paper: Adeniyi Foluso, Monetary Policy and the Real Sector: A Structural VAR Approach for Nigeria, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 10 No. 6, 2020, pp. 339-351. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201006.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Several factors influence the supply of money, some of which are within the control of the central bank while others are outside its control. The need to regulate money supply is based on the knowledge that there is a relatively stable relationship between the quantity of money supply and economic activity and that if the supply of money is not limited to what is required to support productive activities, it will result in undesirable effects in the real sector (CBN 2011). The specific actions were taken by the Monetary Authority (Central Banks) to regulate the money supply in the economy to achieve predetermine macroeconomic objectives are Monetary policy actions. The Monetary Authority deploys various monetary policy instruments (direct and indirect) through the Central Bank of Nigeria to achieve its objectives. One of the major Monetary policy instruments currently used is the Discount rate (Monetary policy rate) which was introduced to replace the Minimum Rediscount Rate (MRR), in 2006 to achieve stable aggregate prices. Monetary policy is one of the macroeconomic management tools used to influence outcomes in the real economy to its desired direction. The basic goals of monetary policy are the promotion of stable prices, sustainable output, and employment. It is expected to affect the real economy through movements in interest rates which would alter the cost of capital and investment in the productive sector. (CBNOP 2014).The Central Bank of Nigeria seeks to achieve price stability through the management of the money supply. The money supply is the aggregate stock currency and other liquid instruments in a country's economy on the date measured. Money aggregate comprises currency in circulation and close substitutes, such as bank deposits, and is informative for aggregate spending and inflation. It thus goes beyond those assets that are generally accepted means of payment to include instruments that function mainly as a store of value. (ECB 2011).In Nigeria, according to (Salihu et al 2018) the definition of money supply includes those financial assets which are highly liquid; Nigeria introduced M3 in 2009 when it included a new financial instrument in its national definition of broad money i.e. securities issued by the CBN and held by money holding sector. Excess money supply (or liquidity) may arise when the amount of broad money is higher than the level required to sustain non-inflationary output growth in the economy (CBN Monetary policy framework 2011). Hence the need to regulate the money supply to achieve the desired level of economic growth.Economic growth is an important macro-economic objective because it enables increased living standards, improved tax revenues, and helps to create new jobs. (Ufoeze, et al 2018). It is the increase in the number of goods and services available in a given country at a particular period. An economy can be classified into four distinct inter-related sectors- real, external, fiscal/government, and financial sectors. The real sector - agriculture, industry, and services - is strategic as it encompasses the production and distribution of tangible goods and services required to satisfy aggregate demand in the economy. Its performance can be used to measure the effectiveness of macroeconomic policies. A vibrant real sector drives economic growth as its impact positively on the production and distribution of goods and services which raise the welfare of the citizenry. The real sector creates more linkages in the economy than any other sector. (Anyanwu 2010).The Nigerian government has adopted various monetary policies through the Central Bank of Nigeria over years to achieve economic growth and despite the increasing emphasis on manipulation of monetary policy in Nigeria, the problem surrounding its economic growth persists. These perceived problems are being claimed to have caused a fast decline in the economic growth of Nigeria (Nwoko et al 2016). Hence the need to examine the effect of monetary policy actions on the real sector.

2. Theoretical Foundation and Empirical Review

- Monetary policy theories have been dominated by diverse beliefs. There is no consensus among economists as to whether monetary policy will bring about economic stabilization. This disagreement divided the economy into different schools of thought (Nwoko, et al. 2016). They are, the Classical view of the monetary policy which is based on the quantity theory of money, the Keynesian view (the indirect relationship between money and price), and the Monetarist view (a modern variant of classical macroeconomist) have been the center of monetary policy analysis.

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

2.1.1. The Classical view on Monetary Policy

- The Classical view of monetary policy is based on the quantity theory of money (QTM), it is given by the expression MV = PY and was developed by an American Economist Irving Fisher. M denotes the supply of money which the Central Bank controls indirectly with the use of base money; V denotes the velocity of circulation that is, the average number of times currency is spent on final goods and services over a given period usually a year; P denotes the price level GDP (Inflation). The classicists believe that given the equation of exchange {(which states that the current market value of all final goods and services (nominal GDP) must equal the supply of money multiplied by the average number of times currency is used in the transaction in a given year (Gholamrezapour and Gang 2018)} and stability in the velocity of money plus the assumption that economy operates at full employment, the change in money supply will only affect price without any effect on real demand, investment and output. (Nwoko, et al 2016).The classical believes the economy is always at or near the natural level of real GDP so that Y in the equation of exchange can be regarded as fixed (Gholamrezapour and Gang 2018). Therefore, if V and Y are constant, then there is a proportional relationship between M & P.

2.1.2. The Keynesian View on Monetary Policy

- On the other hand, Keynesians believe an indirect relationship between output and money supply. The Keynesian believe that monetary policy works by influencing investment decisions through the interest rate. They believe that change in the money supply has effects on total expenditure and output level through the changes in the interest rate and thus mechanism works indirectly. (Chaudhry et al 2012). The variations in the money supply could lead to an increase or decrease in interest rates. A decrease in interest rate will affect aggregate investment and enhance aggregate income and output. This is based on the belief that the interest rate is the key determinant of investment in the market economy. Expansionary monetary policy increases the supply of loanable funds available through the banking system, causing interest rates to fall. (Nwoko et al 2016).

2.1.3. The Monetarist View of Monetary Policy

- Monetarist is a school of thought led by Milton Friedman. This school of thought is a modern variant of classical macroeconomics. They developed a subtler and relevant version of the quantity theory of money (Gholamrezapour and Gang 2018). The monetarists base their views on money supply as the key factor affecting the wellbeing of the economy. They believe that an increase in the money supply will lead to an increase in nominal demand, and where there is excess capacity, they believe that output will be increased. The Monetarists acknowledge that the economy may not always be operating at the full employment level of real GDP. Thus, in the short-run, monetarists argue that expansionary monetary policies may increase the level of real GDP by increasing aggregate demand. However, in the long-run, when the economy is operating at the full employment level, they argue that the quantity theory remains a good approximation of the link between the supply of money, price level, and the real GDP. Also, the long-run expansionary monetary policy only leads to inflation and does not affect the level of real GDP (Gholamrezapour and Gang 2018). Monetarism concludes that monetary expansions influence the real variables such as output and employment in the short-run, while the nominal variables such as nominal national income, interest rates, and prices are influenced in the long-run(Chaudhry et al 2012). The Keynesians believe that fiscal policy influences on economic activity while monetarists believe that monetary policy impacts on economic activity greatly than fiscal policy.

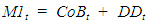

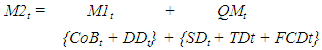

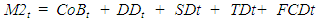

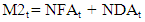

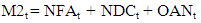

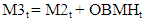

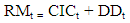

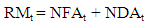

2.2. Monetary Aggregate

- Monetary aggregate is the measure of the amount of money in circulation within an economic sector. It is used to measure the money supply in an economy. According to Walter J 1989 monetary aggregates are measures of the nation’s money stock and the most narrowly defined monetary aggregate. It takes into account one narrow aggregate (M1) and three broad ones (M2, M3, and M4). M1 is banknotes and coins in circulation and demand deposits with issuers of money that is, the greatest liquidity held by residents, M2 is M1 plus deposits with banks and other issuers with a residual term of up to five years, shares in debt funds and payables under repurchase agreements (repos) while M3 adds government securities held directly by resident money holders and issued by the federal government or the Mexican Bank Savings Protection Institute (IPAB) to M2. Finally, M4 has been redefined to include non-resident holdings of all the instruments included in M3 (Morales 2018). Monetary aggregation relied on three categories of aggregates based on the assumption of weak separability among a given set of monetary assets. These are the simple or weighted sum, the variable elasticity of substitution, and the Divisia aggregates (Salihu et al 2018).Current Compositions of Monetary Aggregates in Nigeriaa) Narrow money is made up of currencies, (that are paper notes and coins in circulation) and demand deposits. It is often denoted by M1. It is regarded as a liquid component of the money supply. Narrow money consists of currency outside banks (COB) plus demand deposits.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

2.3. Monetary Policy Actions

- Monetary Policy is the deliberate use of monetary instruments (direct and indirect) at the disposal of monetary authorities such as the central bank to achieve macroeconomic stability (Gholamrezapour and Gang 2018). Governments try to control the money supply because most governments believe that their rate of growth affects the rate of inflation. Hence monetary policy comprises those government actions designed to influence the behavior of the monetary sector (Gholamrezapour and Gang 2018). It is the tool for executing the mandate of monetary and price stability. Monetary policy is essentially a program of action undertaken by the monetary authorities, generally the central bank, to control and regulate the supply of money with the public and the flow of credit to achieve predetermined macroeconomic goals (Dwivedi, 2005 as sighted in Okafor et al 2015).Monetary policy can be neutral, expansionary, or contractionary. Monetary authority engages in expansionary (accommodating) or contractionary (tight) monetary policy, to either increase or decrease the money supply (M) and neutral monetary policy in other to leave the money supply unchanged. If an economy is operating above potential, the monetary authorizes deploys tight monetary policy to bring the economy back to potential and if an economy is operating below potential, the monetary authority deploys expansionary policy to stimulate economic growth. According to ECB 2011, an economy is said to be at potential when its level of output can be achieved using available production factors without creating inflationary pressures.Potential output can be described as an estimate of “full-employment” gross domestic product, or the level of GDP attainable when the economy is operating at a high rate of resource use. Rather than being a technical ceiling on production, potential GDP is a measure of the economy’s maximum sustainable output, in which the intensity of resource use is neither adding to nor subtracting from inflationary pressure. (CBO 2004). Potential output measures the medium-to-long-term level of sustainable real output in the economy (ECB 2011).The main objectives of monetary policy remain to achieve internal and external balances and the promotion of non-inflationary growth in output. Although Monetary policy is designed to achieve price stability and sustainable economic growth (CBNOP 2014), it gives an absolute priority to price stability (Bojan and Ivan, 2013). The targets of monetary policy are the operational target, the intermediate target, and the ultimate targets. The Central Bank of Nigeria manipulates the operating target (reserve money) over which it has substantial direct control to influence the intermediate target (broad money supply) which has an impact on the ultimate objective of monetary policy, i.e., inflation and output. (CBN 2011). Monetary policy instruments are used to manipulate the operating target (reserve money) in other to influence the intermediate target (broad money supply).The instruments deployed by Central banks depend on the level of development of the economy, especially the financial sector. These policy instruments could be direct or indirect (CBN 2011) both the direct and indirect policy instruments have the same objectives, of channeling funds from surplus to deficit sectors, to extend the frontiers of growth and development. (CBNOP 2014). The Central Bank of Nigeria in 1993 abandoned the direct control regime as a natural reaction to the liberalization of the financial sector to adopt the direct control regime through the use of market-driven instruments such as Open Market Operations (OMO). OMO is the most important and flexible tool of monetary policy is open market operations. It is the buying and selling of government securities in the open market (primary or secondary) to expand or contract the amount of money in the banking system. OMO enables the central bank to influence the cost and availability of reserves and bring about desired changes in bank credit and money supply. Reserve Requirements, an indirect instrument is also used by the central bank to influence the level of bank reserves and hence, their ability to grant loans. It can either be lowered/ raised to increase/reduce the capacity of banks to grant loans and thereby influencing money supply in the economy. The two major tools used to achieve the desired level of the reserve are the Cash reserve ratio (CRR) and the liquidity ratio (LR).The third monetary policy instrument currently used by the Central Bank of Nigeria is the Discount Window Operations. This instrument enables the DMBs to borrow reserves against collaterals in form of government or other acceptable securities. The central bank operates this facility in accordance with its role as lender of last resort and transactions are conducted in form of short term (usually overnight) loans. The central bank lends to financially sound DMBs at the policy rate (MPR) which sets the floor for the interest rate regime in the money market (the nominal anchor rate) and thereby affects the supply of credit, the supply of savings (which affects the supply of reserves and monetary aggregate) and the supply of investment (which affects employment and GDP). (CBN 2011). The Bank introduced the Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) to replace the Minimum Rediscount Rate (MRR), in 2006, as a new Monetary Policy Implementation framework. The new framework was designed to achieve stable aggregate prices, including the exchange rate of the domestic currency through stability in short- term interest rates. The MRR represents the minimum interest rate banks can borrow from the CBN while the MPR is a short-term interest rate at which banks can predictably borrow from the apex bank. The MPR serves as an indicative rate for transactions in the money market. (CBNOP 2014).

2.4. The Real Sector

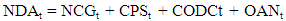

- The real sector of an economy is the sector that produces goods and services to meet the consumption demand of an economy. (Oduyemi 2013). Economic activity is commonly broken down into three sectors: The primary sector, which involves; agriculture, forestry, and fishing, the secondary sector is also known as the industry and it includes manufacturing, processing, or transforming goods, and finally, the tertiary sector(Services) i.e. providing information or services to consumers, such as in IT, tourism, or banking. (Statista 2020).According to USTIC 2017, Nigerian services industries are expected to drive future growth. The sector has shown impressive gains in recent times see Figure (1) Services accounted for over 50% of Nigeria’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019. Nigeria is one of the most open services markets in Africa, receiving an overall score of 27.1 (virtually open) on the Services Trade Restrictions Index (STRI) published by the World Bank even though it’s faced with infrastructure and ease of doing business challenges.

| Figure 1. Source: Statista 2020 |

2.5. Review of Empirical Literature

- Monetary policy can play a major role in alleviating economic growth. Many empirical studies have been conducted to review the impact of this policy on economic growth. Ufoeze et al 2018, investigated the effect of monetary policy on economic growth in Nigeria from 1986 – 2016 using the Ordinary Least Squared technique. The study employed GDP as the dependent variables against the explanatory monetary policy variables: monetary policy rate, money supply, exchange rate, lending rate, and investment. They find that monetary policy rate, interest rate, and investment have an insignificant positive effect on economic growth in Nigeria, Money supply however has a significant positive effect on growth in Nigeria, and the Exchange rate has a significant negative effect on GDP in Nigeria. The study concluded that monetary policy can be effectively used to control the Nigerian economy and thus a veritable tool for price stability and improve output. Using the cointegration and error correction model Obamuyi, and Olorunfemi, 2011 examined the implications of financial reform and interest rate behavior on economic growth in Nigeria from 1970-2006. The results demonstrate that financial reform and interest rates have a significant impact on economic growth in Nigeria. The results imply that the behavior of interest rate is important for economic growth given the empirical nexus between interest rates and investment, and investment and growth. In the same vein, Moyo, C. & Le Roux, P. 2018, examined the impact of interest rate reforms on economic growth through savings and investments in SADC countries for the period 1990-2015 using the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) estimation technique. The authors used three specifications for the analysis; the first one determines the influence of interest rate reforms on savings, the second one analyses the effect of savings on investments while the third one examines whether investments have a positive impact on economic growth. They concluded that interest rate reforms have a positive impact on economic growth through savings and investments. Jelilov 2016 however, discovered that interest rate has a slight impact on growth while examing the impact of interest rate on economic growth in Nigeria from 1990 to 2013.However, Obansa et al 2013 discovered that the Exchange rate had a stronger impact on Economic growth than the Interest rate. Using the vector autoregression (VAR) technique, the study examined the relationship that exists among the Exchange rate, Interest rate, and economic growth in the Nigerian economy from 1970 to 2010, with specific emphasis on the Impulse Response factor and the Forecast Error Variance Decomposition. The period of their study was fractured into two prominent distinctions of the economic era- the regulation era and the deregulation era. Adofu and Salami 2017 examined the effects of monetary policy shocks on some selected macroeconomic variables in Nigeria, from 1983 to 2015 using the structural vector autoregressive technique to model. They concluded that interest rate-shock has a negative impact on real GDP and money supply. Similarly, Mardy and Pahlaj 2015 examined whether monetary policy has any impact on the economic growth in Cambodia using quarterly time-series data from 2000 to 2012. The study applied a multiple regression model to examine the impact of money supply and the interest rate on GDP growth in Cambodia. The results show that the money supply has a positive impact on GDP growth, but the strength of impact is relatively weak, while a change in interest rate over the study period did not affect economic growth, meaning that there is no significant effect of interest rate on GDP growth. Monorith 2019, also finds a similar result for Cambodia. The author studied the significance of monetary policy in the contribution to the economic growth of Cambodia from 2000-2018. The empirical results illustrate that money supply (which represents the monetary policy), inflation, and exchange rate revealed a positive relationship with GDP while interest rate, is confirmed negatively insignificant with GDP. Finally, Twinoburyo and Odhiambo 2018 took a comprehensive view of the theoretical evolution of the relationship and the respective recent empirical findings and discovered that the majority of findings support the relevancy of monetary policy in supporting economic growth, mainly in financially developed economies with fairly independent central banks. Based on their study, they realized that the relationship tends to be weaker in developing economies with structural weaknesses and underdeveloped financial markets that are weakly integrated into global markets. They concluded that monetary policy matters for growth both in the short-run and long-run despite the prevailing ambiguous relationship and recommended an intensive financial development measure for developing countries as well as structural reforms to address supply-side deficiencies.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Description

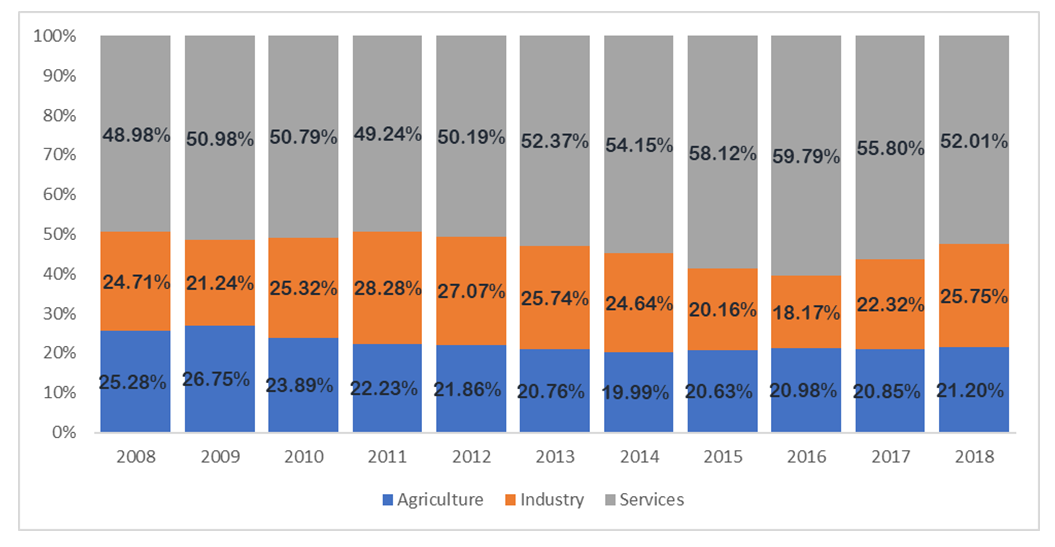

- This study used six domestic variables (real gross domestic product (RGDP), inflation rate (INF), the nominal exchange rate (NER), monetary policy rate (MPR), Prime Lending rate (LR), and monetary aggregate (MA)). All data were sourced from the CBN website. The sample period covers started from the year 2006 {when the Bank introduced the Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) to replace the Minimum Rediscount Rate (MRR) as a new Monetary Policy Implementation framework} to 2019. Though the data were not monthly all through, the annual and quarterly data were transformed into monthly data using Eviews to allow for stable estimations and analyses. Real GDP and money supply are in log form while nominal exchange rate, inflate rate, and monetary policy rate, prime lending rate were entered in their natural form.The two nonpolicy variables included in this study are the Real GDP and the Inflation rate. Real GDP can be used to measure the level of economic activity while the inflation rate {the most well-known indicator of the inflation rate is the consumer price index (CPI)} measures the level of goods and services bought by both households and firms. This study assumes that RGDP and the inflation rate are the two major pillars for the reals sector. The essence of incorporating the RGDP and the inflation rate is to determine how the policy rate influences growth in the real sector.

| Figure 2 |

3.2. Research Methodology

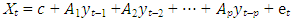

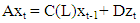

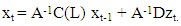

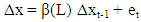

- a) The General VAR modelVAR is a natural extension of the univariate autoregressive model to dynamic multivariate time series. According to Stock and Watson as sighted in Sebastian 2019 VARs are often employed as forecasting and policy tools.

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

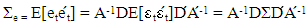

3.3. Identification of Structural VAR

- In this model, variables are RGDP, INF, MPR, LR, MA, NER. The domestic variable comprises two blocks: The nonpolicy block with two variables RGDP, INF, and the policy blocks with four variables MPR, LR, MA, NER. This study followed the idea of Salihu et al 2018 by not introducing foreign variables in the model, as against previous studies (Vinayagathasan 2013, Arwatchanakarna 2017)

| (17) |

4. Discussion of Result and Findings

4.1. Unit Root Test, Optimal Lag, and Stability Test

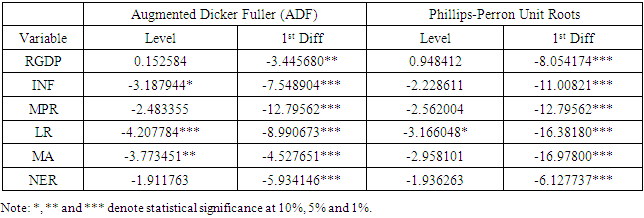

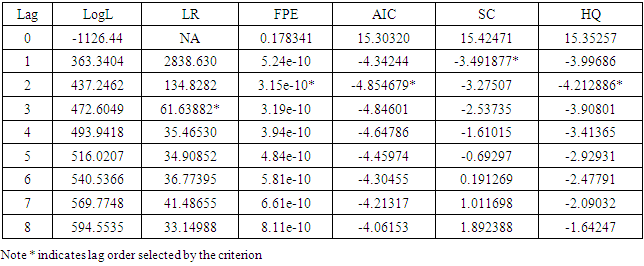

- The study adopted Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Phillips-Perron (PP) tests to determine the level of stationarity of the data. Aside RGDP that is neither returned I (0) nor I(1) by ADF(AIC), the two techniques return the variables as I(1) stationary Table 1. The author chose two-lags as an optimal lag based on the AIC lag-length selection criteria Table 2, 24 lags for the Impulse response function, and variance decomposition. A stability test was also undertaken as part of the diagnostic tests, to ascertain the reliability of the VAR model, the estimated VARs exhibited stability since all roots lie inside the unit circles.

|

|

|

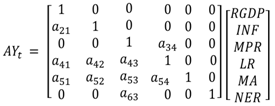

4.2. Impulse Response Function

- This section reports the impulse response function used to understand the dynamic responses of domestic variables to a structural one-standard-deviation shocks. Figure 3 shows the response of domestic variables to the innovation in interest rate shocks. The interest rate shock is neither a contractionary or accommodative shock, it’s a change in policy framework to achieve stable aggregate prices. The first row of Figure 3 contains the response from the output and inflation rate. The domestic output responds positively to the interest rate shock, though the positive response is not statistically significant while the price level reduced significantly throughout the horizon. The innovations to the interest rate significantly reduce and stabilize the domestic price level.

| Figure 3. Impulse Response to an Interest rate shock (MPR) |

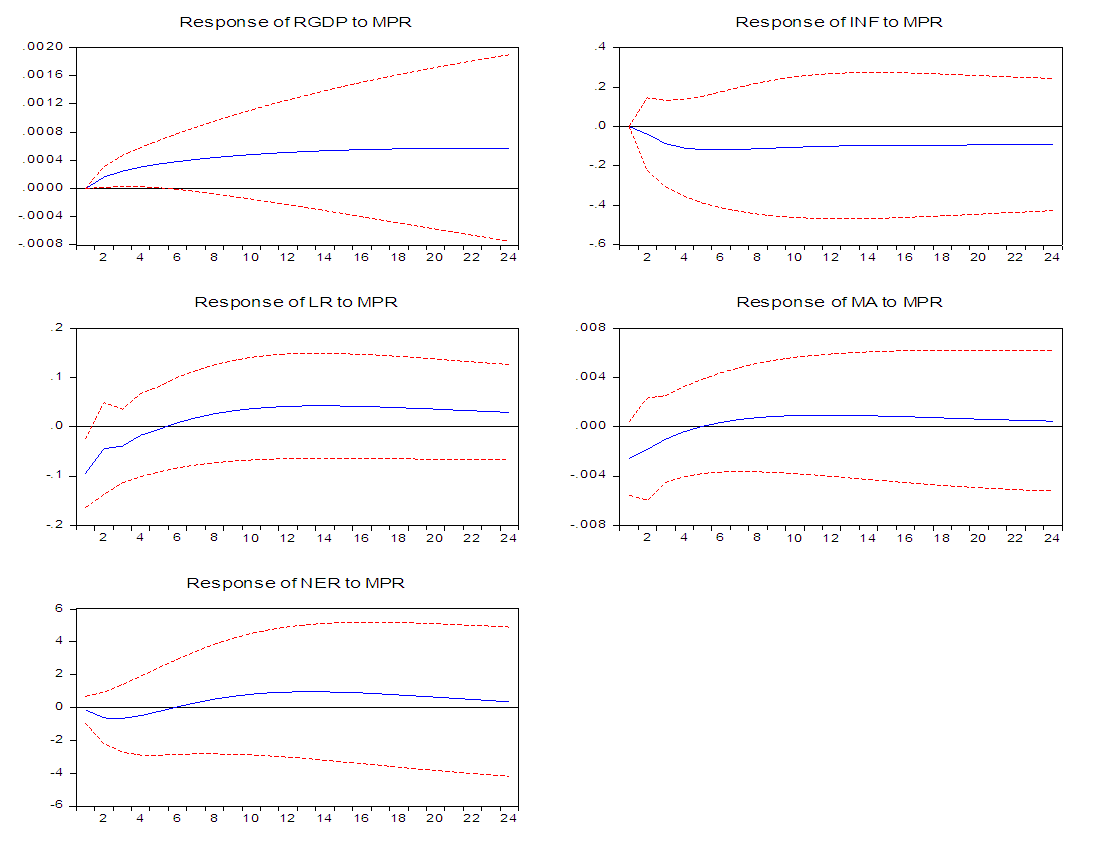

| Figure 4. Impulse Response to a positive money growth shock (Monetary Aggregate) |

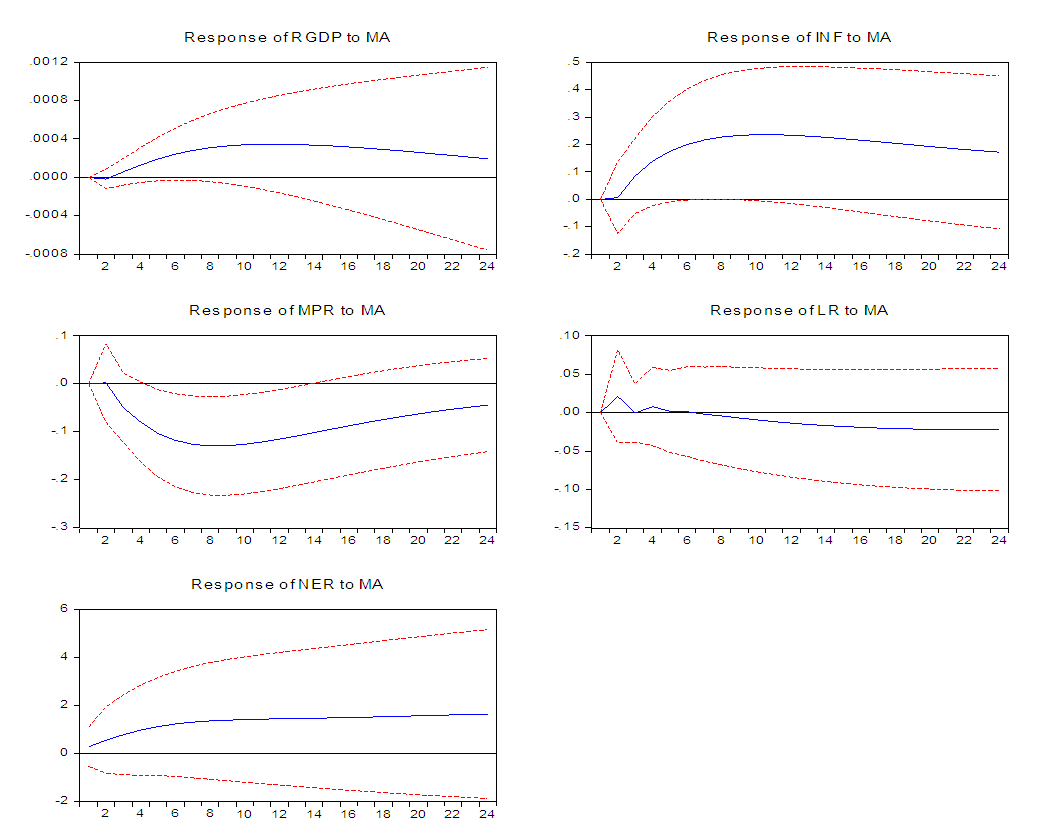

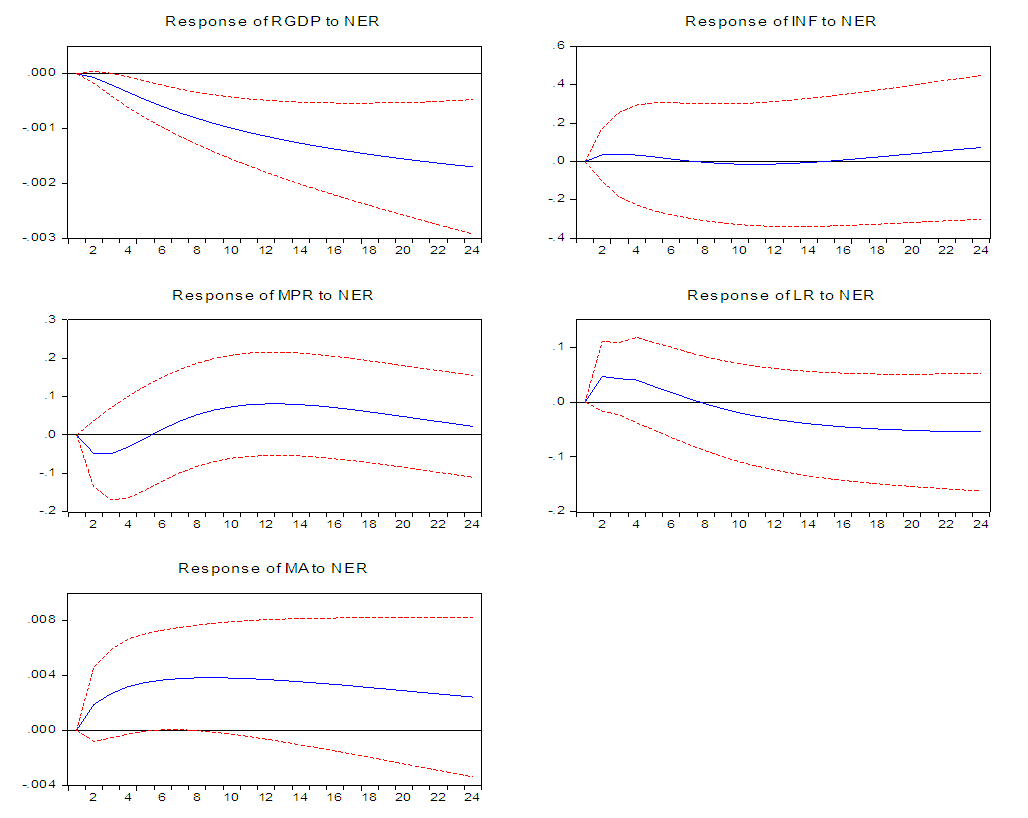

| Figure 5. Impulse Response to a nominal exchange rate shock |

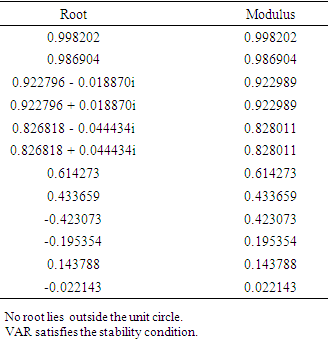

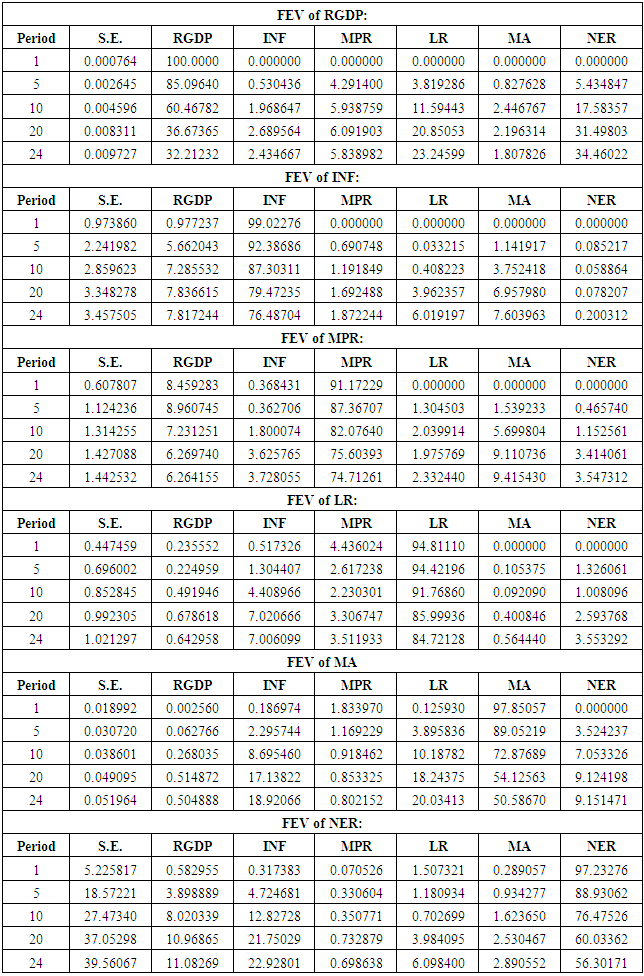

4.3. Variance Decomposition

- Variance decomposition is also a useful tool in investigating interactions among economic variables over the impulse response period. Table 4 presents the proportion of variations in major economic variables that can be explained by shocks to other economic variables. The decomposition values for the 1st, 5th, 10th, 20th, and 24th periods into the future are displayed in that table.

|

5. Conclusions

- This study attempts to investigates the effect of monetary policy rate on the real sector in Nigeria by employing a Structural VAR model using policy and non-policy domestic variables. The focal point of this study is to examine the effectiveness of the Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) introduce as a replacement of Minimum Rediscounting Rate (MRR) in ensuring price stability in the real sector of the economy.The empirical results based on structural impulse response functions reveal that MPR as a policy tool provides significant results. There is substantial evidence that the shock is effective in reducing and stabilizing the price level and increasing output marginally. In the case of the nominal exchange rate, the policy rate shock is found to be effective in the medium to long run. The result suggests that innovations to policy rate are effective in stabilizing price levels, increasing output marginally, and improving the nominal exchange rate conditions. This study supports the idea of Ufoeze et al 2018 that interest rate shocks have a positive but insignificant effect on economic growth in Nigeria, as against Adofu and Salami 2017’s opinion that interest rate-shock has a negative impact on real GDP. Furthermore, result of the findings reveal that changes in output level are more influenced by shocks to nominal exchange rate than shocks to MPR through the Prime lending rate - Obansa et al 2013 also find a similar result - while changes in the price level are influenced by shocks to real GDP, monetary aggregate and MPR through the lending rate respectively. Although as expected, the inflation rate is best explained by its innovations and real GDP, however, monetary policy actions contribute more to variations in price level than real GDP. Empirical findings of both the impulse response and the variance decomposition reveal that shocks to the nominal exchange rate can greatly influence the efforts of the monetary authority in ensuring stable economic growth.Given the importance of international trade and investment in the process of economic growth, this study recommends a stern exchange rate policy action that will have good implications for output growth and complement monetary policy actions in Nigeria.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML