-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2020; 10(5): 293-304

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20201005.04

A Pursuit for a ‘Holistic Social Responsibility Strategic Framework’ Addressing COVID-19 Pandemic Needs

Ahmed Husain Ebrahim 1, Mohamed Buheji 2

1Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Bahrain, Bahrain’s CSR Society, Kingdom of Bahrain

2Founder of the International Inspiration Economy Project, Kingdom of Bahrain

Correspondence to: Mohamed Buheji , Founder of the International Inspiration Economy Project, Kingdom of Bahrain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

COVID-19 pandemic brought with it lots of threats to lives and livelihoods, yet it also exploited lots of hidden opportunities that improve and develop our communities, besides our purpose in life. During such time of uncertainty, there are tremendous needs to protect and reinforce our society wellbeing and life around the world in large. At the heart of these needs are the corporate social responsibility (CSR) and individual social responsibility (ISR), two important thematic responsibilities that need to be well-orchestrated towards the COVID-19 crisis through genuine motives and effective mechanisms. Therefore, this study attempts to provide a ‘holistic social responsibility strategic framework’ where a roadmap could be extracted from for both community and organisational level. The paper attempts to address what, how and where to steer the social responsibility intentions that would help to create the best suitable impact in combating the COVID-19 pandemic. On the basis of a balanced blend of expert point of view and literature review, this paper identifies and recommends a set of value-based socio-economic strategies driven strategies that would manage the expected spillovers of the pandemic and optimise the outcome of social responsibility efforts during major world and national emergencies.

Keywords: COVID-19, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Opportunities, Individual Social Responsibility (ISR), Socio-Economic, Value-based Strategies, National Emergency

Cite this paper: Ahmed Husain Ebrahim , Mohamed Buheji , A Pursuit for a ‘Holistic Social Responsibility Strategic Framework’ Addressing COVID-19 Pandemic Needs, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 10 No. 5, 2020, pp. 293-304. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201005.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is an area that grown in the last three decades and been supported with lots real-world examples to the extent that (CSR) is considered to be one of the strong catalyst factors for sustainable development (Idowu & Leal Filho, 2009). There is mounting evidence in the literature that CSR managed to create a differentiation in relevant to the economic, social, environmental and cultural bottom-line (Crișan-Mitra & Borza, 2015; Behringer & Szegedi, 2016). However, in the one side, random and scientifically-baseless CSR practices by private businesses could lead to controversial outcomes whether for those participating businesses or their stakeholders (Luke, 2013; Moon, 2007; Hawkins, 2006). The unprecedented devastating conditions and the uncertainties associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, present a new challenge to the CSR advocates and leading corporates. The challenge extends to the way that the CSR funds and related projects are allocated, and how they are prioritised towards the most important value-added creation needed during this moment of the world crisis. The financial crisis resulted from the pandemic turbulences has already a negative impact on corporate social responsibility programs (Burlea et al., 2017). Besides, there are proliferating complications of COVID-19 outbreak on societal and economic aspects, which inevitably demand more amplified, prioritised, and strategically optimised CSR implementation and participation. These complications might bring with them a potential risk of ethical lapses in CSR programs implementation, especially if assigned to third parties during the COVID-19 times (Dave, 2020). The other branch of social responsibility is ‘individual responsibility’ which represents the individual’s perception of what he/she should do in order to help society, and level of personal dedication to support their own and others’ wellbeing (Mihaela, 2018). This type of responsibility can take different forms extending from the simple action of natural resources protection to aiding senior people in the community. In pandemics like COVID-19, individual responsibility is a fundamental aspect that could be manifested through responsible behaviour and interest to take an active and proactive role to purposefully help in confronting the challenges that our societies suffer from. This would perfectly be of optimal value when it goes hand in hand with institutions’ obligations and commitments in large. However, in crises, individual responsibilities become more challenging due to the multiple and diverse stresses influencing people’s life wellbeing, and may weaken their normal functioning and limit their mental and physical capacities (Wang et al., 2020; Buheji et al., 2020). In other words, psychological disturbances, social restrictions, and self-isolation associated with the COVID-19 pandemic could be seen as major restrictors to actively pursue or freely enrol in community activities.

2. Review Methodology

- A set of primary and secondary sources was recruited to synthesise the literature review; alongside the authors’ expert point of view has been incorporated in this article work. This has aimed at matching the current rapidly evolving dynamicity and needs of COVID-19 crisis with two concepts: CSR and ISR. The established knowledge is based on notions of providing know-how, real experiences, practical tips, and relevant insights. Based on the synthesis of literature and analytical thoughts, a set of CSR and ISR value-based strategies are proposed.

3. Background Literature

3.1. The Devastations of COVID-19

- The 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has led to a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) as per the declaration of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020a). Enormous threats, at a different level and different extents, have been associated with the pandemic outbreak around the globe. The challenge extends from protecting human being to economic systems and securing the continuity of life itself (Arshad et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2020). According to the WHO figures during the mid of June 2020, around 8 million cases have been confirmed worldwide, and more than 400 million deaths have been reported due to the pandemic (WHO, 2020b). In order control the disease spread, many countries have been prepared and responded through strict measures encompassing wide-scale lockdowns, school closures, isolation, quarantine, travel restrictions, and social distancing (Paital, Das & Parida, 2020; Buheji & Buheji, 2020). However, since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak at the end of 2019, and till this date of writing this article, the human being sufferings is booming from the devastating consequences of the deadly virus, or due to lockdown. Amid the COVID-19 crisis, health resources encounter scarcity and unprecedented pressure; facilities of quarantine and isolation become inadequate with the increasing number of infected and suspected cases; millions of people around the world have lost their jobs; the prevalence of psychological illnesses and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is raising additional concerns; major delays in economic and social development intrude the sustainability agenda; and life after lockdown is predicted with undesirable uncertainty (Lima et al., 2020; Coibion, Gorodnichenko & Weber, 2020; Emanuel et al., 2020).

3.2. The Scope of CSR

- A general examination of existing literature on CSR indicates that there has been a particular interest to trace the conceptual evolution of CSR. Moura‐Leite and Padgett (2011) revealed that the concept - since its origin in the 1950s - has constantly revolved around different practices and philosophies, and it became an important strategic issue in the 2000s definitively. The concept of CSR has been associated with a variety of definitions which entail different underlying perspectives commonly related to society, ethics, environment, economic and organisational practices (Dahlsrud, 2008). One of the most eminent definitions of CSR was introduced by Kotler and Lee (2005, p. 3), explicitly as “a commitment to improve societal wellbeing through discretionary business practices and contributions of corporate resources”. Significantly, strategising CSR has become a prevailing reality in the enterprises’ life with recognition of the importance of closing the gap between the social performance and financial performance (Sharp & Zaidman, 2010; Perrini & Minoja, 2008). Rangan, Chase and Karim (2012, p. 4) argued that every corporation should have a CSR strategy that unifies the diverse range of a company’s philanthropic giving, supply chain, “cause” marketing, and system-level initiatives all under one umbrella. In order to differentiate between two major orientations of CSR, looking at Sims’s (2003, p. 43) CSR definition would be practical for this purpose; the definition is as follows: “the continuing commitment by business to behaving ethically and contributing to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as of the community and society at large.” On the basis of this definition, it is obvious that CSR concept is primarily aligned to two levels of analysis: first, the Meso-level (organisation) which is an “internally-centric CSR” and second, the macro-level (society) which is an “externally-centric CSR”. These CSR orientations were described by many CSR scholars (Schwartz and Carroll, 2003; Sims, 2003; Babiak and Trendafilova, 2011; Carroll, 1991; Coombs and Holladay, 2012). At organisational level, a business may practice CSR through its sound commitments towards ethico-legal obligations, employees’ quality of life, work-life balance and financial success. While at the society level, enterprises’ CSR efforts can be focused on civil society (social welfare), philanthropic contributions, promoting public health, nurturing public resources and environment protection, especially in areas in which a business carries out its operations. It is worth mentioning here that corporates’ motivations toward CSR could be multiple or different, and that evidence indicated that there could be many reasons of why a corporate or a business entity may participate/engage in CSR activities; including financial, reputation, legitimacy, competitiveness, cultural and political interests (Graafland, & Mazereeuw-Van, 2012; Riillo, & Sarracino, 2014).

3.3. The Scope of ISR

- Individual Social Responsibility (ISR) can take many forms and involve a variety of dimensions to which an individual’s actions can be manifested, and that several scholars of social responsibility attempted to analyse and introduce the concept of ISR through holistic and interactional models (Davis, Rives & de Maya, 2017; Mihaela, 2018). ISR has been majorly viewed at the interpersonal level but considered as a key contributing factor for realising the corporates’ strategies for a more responsible, moral, transparent and respectable institutional role and behaviour (Ibid). It could be rationally argued that ISR is central for leveraging CSR because a corporate is made up of individuals, and in return, their behaviours and actions create and determine the culture of the that corporate or enterprise. Fundamentally, ISR, as part of everyday life, requires citizens’ decisions, choices and acts to be supportive for social, economic, social and environmental wellbeing (Davis, Rives & Maya, 2017), and indeed with being oriented and motivated towards legal and ethical commitments and discretionary contribution (Benabou and Tirole, 2010). Further, ISR means that individuals need to possess adequate awareness and exhibit positive behaviours towards their own wellbeing including psychological, physical, social and economic aspects (Ecclestone, 2017; Resnik, 2007; Yoder, 2002); and beyond that, they need to demonstrate responsibility towards others’ wellbeing through many ways like respect for the rights and feelings of others, ethical consumption and purchasing behaviour, sense of caring and urgency, help others in distress, support the needs and welfare of others, and act through solidarity and cooperation values (Carrigan et al., 2005; Barnett, Cafaro & Newholm, 2005; Schmidtz, Goodin, & Goodin,1998; Gyekye, 1997).

4. Literature Review & Analysis

4.1. CSR Strategies for a Better COVID-19 Situation

- On the basis of literature examination and authors’ relevant and extensive experience in the field of social responsibility, the authors identified and suggested the following five CSR strategies to which a business model could be aligned and help to earn stakeholders’ acceptance and support for intended CSR initiatives in times of COVID-19 pandemic. These are:

4.1.1. Strategy 1: Inclusive Assessment & Systematic Evaluation Model

- In the light of normal living conditions, literature has stressed the significance of adopting an appropriate and tactful approach to evaluate a company CSR performance; a process that represents one of basic quality management activities. However, such process of internal self-assessments could become more challenging during pandemics like COVID-19; as it has imposed a heavy toll on many enterprises financial robustness, and subsequent tendency towards maximising or seizing the opportunities of survival, reshaping/readjusting their structures and operations, and rising the tolerance of absorbing the systemic economic shock (Bartik et al., 2020; Didier, Huneeus, Larrain & Schmukler, 2020); hence in such devastating circumstances the potential or capacity of pursuing societal value-driven investments seems collapsed. However, these suffering organisations are not exempted from demonstrating an acceptable level of CSR through immediate actions and medium-term measures such as the ones warranting the re-employment of laid-off employees. On the other side, large corporates sustaining excellent financial positions need to take lead responsibility in the community and economic ecosystem; and therefore, internal assessments become vital.Jankalová & Jankal (2017) conducted a multi-criteria analysis through which two excellence models have been endorsed as assessment frameworks for social responsibility; these are the EFQM Excellence Model and the Malcolm Baldrige Model for Performance Excellence. Recruiting these models for CSR assessment has been linked to quality thinking, public value creation, inspiration and integration, and sustainable future creation. Further, the criteria of these assessments in relation to CSR significantly involve the process and results dimensions. Such dimensions compensate for the communities need to mitigate the effect of the COVID-19 related devastations. Using such dimension in improving and re-engaging CSR strategies and related activities can help in preparing the organisation and improve its intrinsic power (such as the employees and the working environment), and extrinsic level (such as the community, besides the economic and environmental aspects).Besides the self-inspection; benchmarking CSR related performance during the COVID-19, against similar organisations (that can be of similar size or similar industry) can help to lay the foundations for determining priorities of CSR (Valackiene & Miceviciene, 2012). According to Graafland, Eijffinger & SmidJohan (2004), benchmarking CSR can serve several purposes; it improves company’s transparency and accountability, provides simplicity and a systematic approach for judging CSR performance/ contribution, and guarantees a more objective of CSR. However, this should not be based on imitation mechanism rather than warranting supportive/complementary contributions, closing gaps in areas of needs, trying new ideas and ways to address CSR matters amid COVID-19 crises. Particularly, this process must focus on realised value-creation, like enhancing public prosperity, people’s goodwill and trust. In the meanwhile, the organisation can run a cost-benefit analysis and identification of risk and opportunities, all in the context of weighing up enterprise’s resources and capacities against its social obligations.Context assessment is fundamental for determining priorities of immediate and future CSR attention, resources allocation and investments. For example, with the COVID-19 outbreak, identifying the set of circumstances surrounding the corporate and its CSR strategy innovation requires the consideration of four key contexts to be assessed and scrutinised: 1) The organisational context: this context relates to questions like: Does the organisation help its current or laid-off employees through best socio-economic practices? Is the health and safety of the employees being a top priority? Has the company adjusted to COVID-19 through strategic market re-evaluation, change management tactics, and learning and development? And does it promote institutional resilience and transparent communication during the crisis? (Wu et al., 2020).2) The industrial context: a study by Hoepner and Yu (2010) implies that CSR value should be assessed within the context of the industrial business processes, i.e how the organisation is using the opportunities for deploying resources and communicating the social responsibility practically to its culture by engaging intangible activities like inaugurating eco-efficient production technologies. Significantly, organisations may engage in evolving activities, which are of societal value, in harmony with the industrial adaptation during crises, as the case during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, in the restaurants industry, food outlets have heavily relied on offering take-out food only and online orders. In education and training industry, new and innovative ways to deliver the content of academic and professional development programs are being used through several technologies and interactive applications including but not limited to virtual whiteboards, teleconference platforms and live television broadcasts (Basinger, 2020); in the healthcare industry, telemedicine has witnessed drastic usage rates among hospitals and outpatient clinics, as an alternative and ideal solution in relation to the social distancing measures, and hence eliminating the risk of exposure to the virus (Bashshur et al., 2020; Hollander and Carr, 2020).3) The community context: during the COVID-19 crisis, identifying issues and gaps emerging at domestic level necessitates organisations to get involved and make a decision best to serve community’s health and quality of life. The COVID-19 induced burdens have opened many avenues for CSR contributions and acting with fierce urgency to address immediate needs of health care operations, support food pantries and meal programs (especially for quarantines), make philanthropic donations and contribute to community-based emergency response funds, and many other areas of demand. 4) The global context: the need of countries to act immediately and to prepare, respond, and recover is inevitably a national priority and international responsibility (Mazzuoli, 2020). Buheji and Ahmed (2020) see that among this darkness comes lots of opportunities for each field, and CSR is not an exception. While the United Nations has allotted a US$2 billion global humanitarian response plan for the most vulnerable, it is projected that developing countries could lose at least US$220 billion in income. Therefore, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has called for US$2.5 trillion to help them (UNDP, 2020). This could bring in more opportunities for corporates and SMEs in developing countries along with more sustained and synchronised efforts from individuals, institutions, corporates plus NGOs. These institutions should acknowledge the value of the CSR programs and how they could help during such times of uncertainty, which could protect and reinforce our social wellbeing and life around the world in large. The CSR contributions within the global context could extend over the spectrum of humanitarian aids delivery to supporting funds of R&D. An example of that aspect, Microsoft corporate has dedicated $20 million in January, 2020 for the initiative of Artificial Intelligence (AI) for Health to reinforce those on the front lines of COVID-19 research, and help generating the global value of better understanding and combating COVID-19 disease (Kahan, 2020).

4.1.2. Strategy 2: National and International Communication Model

- In times of terrible and large-scale crises, the instilment and assurance of coherent, practical and innovative ways of communication and synchronisation amongst governmental bodies, private institutions, NGOs, public and all relevant stakeholders is in itself an imperative social responsibility (Idowu et al., 2017). Communication during a crisis is a collective responsibility which is of critical importance within any response and preparedness strategy, and that it aims to better protect interests of the whole group (Quinn, 2018), to enhance citizens response (Hyvärinen et al., 2015), encourage a successful clearing up of the emergency situation (Le Roux, 2013), and indeed to better generate favourable CSR attributions (Ihlen et al., 2011). Fascinatingly, crisis communication and CSR practising are closely related and mutually reinforcing; findings of Hsu’s (2006) study indicated that corporates that did not practice CSR during its crisis were unsuccessful in its crisis communication, and that CSR is associated with crisis communication in terms of public perceptions.The COVID-19 crisis motivated many institutions to constantly emulate best practices of risk communication models through ‘unified group thinking’ and ‘wide-scale observation of future vulnerabilities’. Such communication models there should be part of the CSR effort, since they help in adopting proactive changes and to contain the emergency situation while gaining public trust (Balog-Way and McComas, 2020). Such actions should be visualised through the lessons which had been drawn from earlier public health emergencies. De Sa et al. (2009) cited major lessons attributed to fractured communications systems in relation to the disasters caused by SARS, H5N1 and Hurricane Katrina. Most of the lessons realised were related to failures in the communication models, such as the inter-institutional coordination, unmanaged rumours, and massive information could hinder an effective, efficient and timely mobilisation and effective management of public health and disaster resources when dealing with a pandemic like COVID-19. A robust communication model could be embedded into the COVID-19 response plan to encourage coordination between all concerned parties, and that NGOs should demonstrate a catalyst role to promote public interest to both risk communicator and response initiator. As a domestic level example and as a response to frontline medical missions against COVID-19, ‘Hilton’ and ‘American Express’ have partnered to donate up to 1 million hotel rooms in order to assist health practitioners in isolating themselves; many other exemplar models and forms of corporate citizenship have been informed by Olphert (2020). At the global level, the Inter-agency Standing Committee IASC underscores ‘coordination’ as an overriding principle of action to guide the humanitarian effort in response to COVID-19 emergency, through stressing on integrating COVID-19 response actions into humanitarian response architecture and mechanisms and accountabilities, and avoiding parallel coordination structures (IASC, 2020).

4.1.3. Strategy 3: Civic & Community Engagement Model

- This strategy model is not absolute, and it has interdependency with all other strategies of CSR. Ensuring that concerned individuals and agencies are being informed about issues and decisions concerning their health, socio-economic conditions and overall life is in itself a form of responsibility, assistance and solution. This should support them to make informed decisions to adapt to the stressful circumstances, protect themselves and augment their readiness and response plans, whether at the personal, professional or social level. Wu et al. (2020) prescribed three interrelated strategic mechanisms in order to reinforce organisational cohesion and psychological wellbeing of HCWs; they were based on communication, engagement and empowerment principles, cited as follows: a resilience-focused leadership, structured crisis communications, and continuum of staff support within the organisation. One of the highlighted tactics is the peer support program called RISE (Resilience in Stressful Events), developed by Johns Hopkins and adopted in more than 30 U.S. hospitals. RISE responds to calls 24/7 and dedicates in-person psychological first aid and emotional support to workers from different health specialities. The strategy of ‘community engagement’ is of utmost significance at the national level as well. According to Moon (2020), major reasons linked to the dramatic drop of COVID-19 infection rate in South Korea were the agile, adaptive, and transparent actions by the country government, along with citizens’ active participation and engagement in anti‐COVID‐19 measures; in return, this has been reflected positively in public cooperation and trust levels. A study by Chen et al., (2020) investigated how to promote citizen engagement through government communication during the COVID-19 outbreak, it was found that governments can facilitate citizen engagement through social media functions, customised crisis information, deploying artificial intelligence and cloud computing technologies, and dialogic loop; in return, this could help to satisfy the needs of citizens to a great extent. Concurrently, the overall strategy can be viewed through evidence indicating that positive public psycho-behavioural reactions and social participation in COVID-19 related events could be facilitated by properly designed and targeted intervention programs of knowledge improvement towards the COVID-19 outbreak (Li et al., 2020). As an attempt to disseminate the message and sense of collective responsibility to the different parties of the community and members of the society, crisis management committees in many states have developed slogans, logos and hashtags as part of launched COVID-19 combating campaigns. An example of this aspect, KSA’s awareness-raising campaign which embraces the slogan ‘We’re all responsible’; and similarly Bahrain’s slogan which is “Be responsible” - see Image 1.

| Image 1. Two exemplar slogans aimed at encouraging collective responsibility during COVID-19 |

4.1.4. Strategy 4: Development & Implementation of COVID-19 Centric CSR Initiatives Model

- On the basis of the aforementioned strategies and CSR motivations, the development of CSR programs and activities would be applicable and of value for meeting the community needs and creating a win-win situation for all. CSR amid the COVID-19 pandemic is an imperative and crucial priority for better, healthier, stronger communities, economies and capacities. Many forms of CSR have been adopted by several firms in different industries worldwide; however, it is still not clear to what extent these contributions are up to the level of public expectations. Field surveys and applied research are needed in this significant area to optimise the mechanism, value and impact of every contribution and response, whether carried out internally or externally. A recent research Vethirajan et al. (2020) showed the importance of private firms’ response towards the community during the COVID-19 pandemic, in both developed and developing countries. The Vethirajan team aimed at identifying leading industries CSR practices in the COVID-19 pandemic period using secondary information. The study found that Indian industries have developed their CSR model based on responding to immediate community needs, but in alignment with the Indian ‘Prime Minister's Citizen Assistance and Relief in Emergency Situations Fund’ which was found during the pandemic. The study showed also how certain organisation focused their contributions towards healthcare sector through donations, providing health resources (like beds, masks, sterilising materials, etc.), and temporary health facilities. In another study conducted by Talbot and Ordonez-Ponce (2020) explored how the Canadian banks are using CSR models to support their clients and communities three type of approaches were identified: sweeping actions approach, cautious actions approach, and wait and see approach. The ‘sweeping actions approach’ of certain Canadian Banks reflects the a proactive response spirit which is not limited to the bank clients, but extends to social initiatives such as fast disbursement of financial aid programmes, including scholarships and students loans suspension without interest; and donations to food banks, psychological support services, and community services for vulnerable people affected by the pandemic. In the ‘cautious actions approach’, the pattern of commitment to social obligations was lower in this cluster than for the ‘sweeping actions’ approach. In the ‘wait and see approach’, those banks’ adopted programmes were majorly limited to their clients and were among the least generous towards their community in times of crisis. Research of Francis and Pegg, (2020) emphasise the importance of creative thinking in defining how to run a CSR program for rural areas during the time of national emergencies. The researchers should that carrying socially distanced school-based mechanism with the leadership of a specific person-in-charge of the project help in resolution and continuity of aid. Such creative programs if adopted by NGOs and humanitarian actors, would surely help in delivering essential services to poor and vulnerable communities.

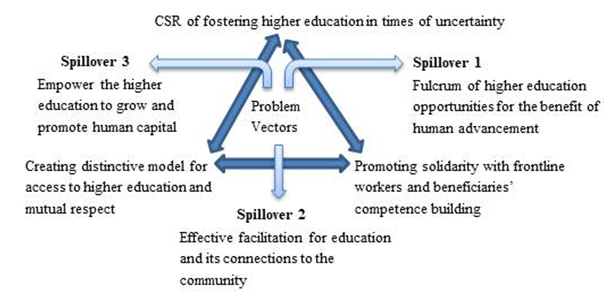

4.1.5. Strategy 5: Strategizing Impact & Outcome Model

- Crucially, the foresight, prediction, identification, mapping and analysis of impacts created by socio-economic projects represent an important aspect to communities’ development, particularly by means of augmenting the stock of knowledge, and fostering the quality of life (Buheji, 2020). According to the author, the implications of understanding the influence of socio-economic projects are diverse, and comprise opening up horizons for positive change in behavioural and social norms, for prioritising community issues, for predicting the reality of business success, and for reinforcing the collaborative efforts towards the sustainable development goals SDGs. Most important, the author has offered a practical guide and tools to determine and map the spillover effects in relevance to CSR projects, and hence that it can be recruited for today’s CSR contributions steered towards COVID-19 related devastations and challenges. As an example, in this article, Buheji’s technique is conceivably applied on Ahlia University CSR initiative. This initiative has been adopted in line with the national efforts to support COVID-19 combat campaign; it comprised a discount to the current students on their tuition fees, and a 50% scholarship scheme dedicated for front line workers (of different ministries) and their children (new applicants) in appreciation of their vital role in confronting the pandemic. Figure (1) illustrates the exemplar model.

| Figure (1). Impacts and Spillovers of the Discounted Scholarships for the COVID-19 Front Line Workers |

4.2. ISR Strategies for a Better COVID-19 Situation

- By applying the aforementioned methodology used to identify the CSR strategies, the authors identified and suggested the following five ISR strategies models to which the community members are expected to demonstrate during these times of COVID-19 crisis. These are:

4.2.1. Strategy 1: Self-Awareness Development Model

- Dealing with the situation of COVID-19 pandemic in terms of protective measures, understanding the illness nature, and ways of promoting the bio-psycho-social health of an individual or people surrounding him/her are inevitably requiring robust self-awareness levels and subsequent healthy behaviour, and sound alteration/adaptation to the new life needs. Due to the significance of self-awareness development strategy as a fundamental social responsibility, continuous efforts and attention by the different stakeholders combating the COVID-19 outbreak are always needed to effectively apply this strategy on a wide scale. Fascinatedly, Wolf et al. (2020), through a cross-sectional study, sought to determine COVID-19 awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and related behaviours among U.S. adults who are more vulnerable to complications of infection, they found that many adults with comorbid conditions lacked critical knowledge about COVID-19 and, despite concern, were not changing routines or plans. People should be aware of the wide-scale impact of the collective self-awareness to reach the desirable level of control on the pandemic. A study by Huang et al. (2020, p.1) was based on analysing the control strategies during the first five months of 2020 in Singapore, the conclusion of their study explicitly stated as “Contact tracing and self-awareness can mitigate the COVID-19 transmission, and can be one of the key strategies to ensure a sustainable reopening after lifting the lockdown.”

4.2.2. Strategy 2: Psychological Resilience

- As was mentioned earlier, that the COVID-19 outbreak-related uncertainties, devastations, misinterpretation of the pandemic, and need of adaptation have been associated with the prevalence of psychological symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety and sleep problems among both front line workers and general public (Du et al., 2020; Varshney, Parel, Raizada & Sarin, 2020; Huang & Zhao, 2020). As a result, Buheji, Jahrami and Dhahi (2020) structured and proposed a framework to help to practise resilient practices such as visualising a ‘stress mitigation strategy’ during a long-term pandemic. This framework is aimed at shifting individuals and communities from ‘living with the uncertainty’ to the building the ‘capacity of coping with uncertainties’. Within the core of that resilience, a strategy is the individuals’ responsibility to build their ‘social capital’ and establish life goal/s, that would give them a sense of achievement and hope. Therefore, efforts must be made to empower people, particularly those who faced traumatising work or life conditions, to seek psychological support if needed without stigma or negative ramification. One of proposed and proactive methods of support is to instil the practice of psychological resilience as an ISR to enlarge the capacity of preserving and protecting the psychological and emotional wellbeing of community members as a whole (Santarone et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020). Vulnerable segments of community, like seniors and parent, should also be paid adequate attention by designing tailored psychological resilience models on the basis of recent research and current experiences. For instance, a study conducted by Ebrahim, et al. (2020) found that amid the COVID-19 outbreak in Bahrain, about 18% of sampled parents had moderate-severe anxiety symptoms (score ≥10 on GAD-7), and that their intention to seek information about COVID19 transmissibility, symptoms, treatment, and complications as a predictor factor for anxiety OR: 0.5 [95% CI 0.3-0.8], p < 0.01.

4.2.3. Strategy 3: Interaction with COVID-19 Information Model

- The dynamics and nature of how a person is being involved with COVID-19 related information is also a matter of self-awareness. However, this domain deserves a standing alone segment as it represents a vital and complex aspect during these times of pandemic due to several reasons like its effects on psycho-behavioural responses of public, the importance of identifying and satisfying the public needs for COVID-19 information, the massive COVID-19 related media consumption, and the matter of rumors spread (Qian et al., 2020; Ebrahim et al., 2020; Mejia et al., 2020; Jones, 2020). Therefore, ISR should be demonstrated within this aspect through at least four important strategies: first, the aptitude to recognise rumours and false information broadcasted through some social media sites, and avoidance to participate in spreading such information; second, practising a wise COVID-19 information-seeking behaviour that relies on trustful sources of relevance to help to overcome the pandemic challenges; third, nurturing our minds with positivity and ability to cope through self-education and psychological resilience; forth, being conscious about how much time and what type of content to be consumed or communicated via social media.

4.2.4. Strategy 4: Caring Families and Friends, and Society at Large Model

- During the first five months since COVID-19 pandemic, abundant opportunities have emerged for people to express and act on their ethical and social obligations towards others. The society members could involve in many aspects of ISR including but not limited to philanthropic contributions, participation in volunteering activities, wise resources consumption and share, and reflection and re-investment in empathy, compassion, courage, solidarity and grace for those who have been affected (whether in their health, economic or social statues), for those putting their own lives on the line, and for those who have lost their loved ones due to the virus (Galea, 2020; Smith, Ng, & Ho Cheung Li, 2020). On the other hand, denying and rejection the acts of stigmatisation, discrimination, mistreatment, and racism have become fundamental to be internalised and exemplified in one’s ISR. These community destructors are of potentially negative impact on civic security, the success of public health agenda and many dimensions of citizens’ welfare (Logie & Turan, 2020). At this critical time, dysfunctionality in the family dynamics and wellbeing due to imposed quarantine or staying home for too long, is an expected matter of negative bio-psycho-social effects on the members of the family (Brooks et al., 2020; Buheji et al., 2020). According to Ebrahim et al. (2020) who investigated the COVID-19 information-seeking behaviour (COVID-19 ISB) among parents and its potential association with anxiety symptoms, had found that parents’ utmost priority, when they sought COVID-19 information, was to know ‘how to apply a proper self-quarantine’. Such a result stresses the criticality of parents’ role and responsibility of being capable of managing and controlling risks of family health turbulences and negative life experience may result from the confinement and lockdown situations. Buheji et al. (2020) presented a holistic framework for parents to help them adopt effective coping strategies and foster balanced children's physical and mental wellbeing during the outbreak of COVID-19. Such scientific attempts are of value to help the community members carry out their responsibility towards the building block of the society ‘the family’ on the basis of evidence and best practices of confronting the pandemic devastations.

4.2.5. Strategy 5: Readiness & Willingness to Contain the COVID-19 Model

- Contact tracing and isolation or quarantine of infected or exposed individuals is a core tactic to lessen the transmission of COVID-19 disease and protect the community. Those individuals’ responsiveness, reactions, cooperation and quality of disclosed information would play a major role for the success of protection plans. It is also important to have a resilience towards the process of contact tracing, and that there should be a sensitive and objective balancing between the privacy/confidentiality of a positively confirmed case and the benefits to society (Chan et al., 2020). Within this context, ISR should be established through building the capacity of mutual understanding, altruism and proactivity. Furthermore, the willingness of people to take steps to self-quarantine or seek testing (when required) is imperative. Despite the public health benefits of quarantine, the adherence towards this obligation could be difficult; and that published literature showed that the rates of adherence are variable (Webster et al., 2020).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Raising the Capacity vs. Demand

- This study links between the strategies of CSR and ISR and risks identified for the COVID-19 pandemic and its spillover. The balance between risk and opportunities, are weighed-up to apply the formula of inspiration economy where CSR should play a role in raising the ‘capacity vs. demand’, instead of normal ‘supply vs. demand’. The strategic models proposed target to align the national resources and the capacities towards the social obligations that arise due to the pandemic. Some of the CSR strategies address even the future demands that need attention, such as eco-efficient production technologies. The models also ensure engagement of the stakeholders in the process of delivery which help to develop the common societal values, while creating harmony. The proposed models also could be used as a tool for identifying issues of necessity and gaps emerging at the domestic level, especially in the areas of live and livelihood, with focus on both community’s health and quality of life. The COVID-19 induced challenges opened many avenues for CSR strategies to get involved with the urgency of the immediate needs of the overwhelmed and stretched resources of the public health authorities and hospitals, besides supporting the medical staff and front-line workers with food pantries and meal programs.

5.2. Communication Models that Complement CSR Strategy

- The most tools of any emergency crisis is the communication model. Such models are even more important if the crisis is a pandemic which requires collective responsibility and engagement with effective response, if availability and preparedness are to be fit for the challenge of a highly contagious disease as COVID-19. The communication model encourages ‘unified group thinking’ and ‘wide-scale observation’ of future groups vulnerabilities.The communication model targets also to build interrelated strategic mechanisms which could reinforce organisational cohesion and psychological wellbeing. Such cohesion and wellness would lead surely to more resilient leadership, structured crisis communications, and continuum of staff support within the organisation.

5.3. Community Engagement Strategies

- The common thread of all the explored and proposed CSR and even ISR strategies focus on positive public psycho-behavioural reactions and social participation. This level of engagement is very important for combating a pandemic as COVID-19 which have several and rapidly evolving challenges that are intensively and widely devastating the socio-economies of communities and nations. The strategies proposed in the paper help to address how and where to use CSR initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic can create socio-economic benefits on both the short- and the long-run.

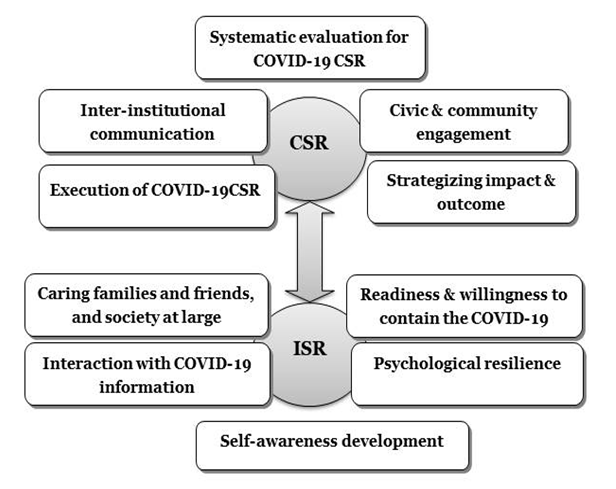

5.4. The COVID-19 Driven CSR/ISR Strategies Holistic Framework

- This paper proposes a holistic framework that blends together the value, the cultural and the socio-economic demands that needs to be address during the COVID-19 pandemic or similar national and international emergencies. As shown in Figure (2), the proposed framework is flexible and can be used in any sector and by any entity. The implication of this framework is that it encourages initiatives, development of a unified culture that is built on collaboration and solidarity. Besides, this holistic framework incentivises and promotes positive behaviours.

| Figure (2). Holistic Framework of CSR and ISR strategies for Mitigation of COVID-19 Pandemic Risks. (Developed by the authors) |

5.5. CSR Spillovers

- COVID-19 is a human, economic and social crisis. Immediate CSR investments can have direct tangible impacts through humane support and economic relief for vulnerable and suffering people, frontline workers, collapsed enterprises, and countries are experiencing fragility. On the long-run, the risk of having long-lasting scars on both communities and economies could be mitigated through understanding the spillover expected and direct investments coming in this direction. As CSR involves internal and external practices, relevant spillovers of COVID-19 CSR impact could be viewed and mapped from different angles including but not limited to: 1) moral and social values like social cohesion, social responsibility, unity, solidarity, equity of access to resources; and 2) economic values like: novel response and readiness strategies, renovation of policies and standards, capacity of change.The CSR spillovers is a type of mindset that could help to calibrate overtime the approaches that need to be taken towards reforming and reframing all the efforts that could improve the immunity of the organisations and communities against similar crises in the future. Both the framework and the spillover mindset could help to improve the lessons learned during the pandemic. Creative statistical and market analysis models, artificial intelligence and e-technologies can further be integrated with the framework when needed.

5.6. Study Limitations and Implications

- The limitation of this study is that its framework was not tested in any setting or in any community. However, this study carries lots of implications for national emergency committees, COVID-19 pandemic mitigation teams and most important a guide for any citizen or organisation would like to know how to contribute in an effective way that would lead to the alignment of the efforts towards enhancing the readiness and preparedness of the country or the community.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML