-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2020; 10(3): 149-162

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20201003.05

Determinants of Small and Medium Enterprise Trade Competitiveness in Tanzania’s Agriculture Sector

Lynn Lisa Lyimo

School of Economics, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China

Correspondence to: Lynn Lisa Lyimo, School of Economics, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Tanzania’s small and medium enterprises make up about 50% of its Gross domestic product. Of that 50 %, most SMEs involved in the agricultural sector. There are more than one million entrepreneurs in Tanzania running micro (informal) businesses, small to medium businesses; however, the small businesses rarely turnover to medium businesses. The purpose of this study is to provide more insight into the determinants of SME competitiveness in a developing environment by shedding light on the agricultural sector in Tanzania. These determinants offer a basis for business competitiveness. The study uses a combination of theory and econometric analysis, through the collection of field data from a selected sample of 100 SME’s. One of the significant findings is that the Government support determinant had a negative correlation to increased competitiveness, which shows that policies and regulations are not as strong as they should be and are not as enforced efficiently and clearly. Determinants like the level of education and training skills also hold a significant role in maintaining competition in business. Finance holds a substantial part of the challenges faced by SME’s in Tanzania, restricting growth through lack of availability of capital. Other challenges include Unfair taxation laws and lack of technology. The findings suggest that better government policies and regulations should be put in place to support SME growth, and the financial institutions need to reform their loan structures to accommodate the different stages of an SME.

Keywords: SMEs, Competitiveness, Tanzania, Agriculture sector

Cite this paper: Lynn Lisa Lyimo, Determinants of Small and Medium Enterprise Trade Competitiveness in Tanzania’s Agriculture Sector, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 10 No. 3, 2020, pp. 149-162. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201003.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The term “SME” in Tanzania refers to micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, although also the term MSME is used.Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are a large part of income creation and employment. SMEs from all over the world and in Tanzania quickly started with minimum requirements of investment, technology, administration, and utilities are not as persistent as it is the case for large enterprises. Enterprises do not have a single code of conduct; hence they can also be created in the countryside and thus add value to the agro products and, at the same time, facilitate the spread of enterprises. Indeed, SME's development is closely associated with the more even-handed supply of income and, thus, plays an essential role in alleviating poverty. Also, SME’s provide grounds for new entry entrepreneurs. Of all the businesses in Tanzania, 95% of them are Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and are represented by about 35% in the country’s GDP, according to the Tanzania Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture (TCCIA). In Tanzania, the potential of the SME sector to be discovered is enormous; however, due to the existence of several constraints hampering the development of the industry, it still is underdeveloped. These constraints include unfavorable policies, immature infrastructure, deprived business development services, difficulty in gaining access to finance, ineffective synchronized institutional framework.SMEs need to provide practices of business competitiveness and strategy. These practices are highly dependent on the quality of the institutions, marketplace, and organs that encourage or discourage them from learning new ways of doing business, increasing competitiveness, and making investment decisions that elevate innovation into their business strategies. The weaker the environment, the less likely SMEs are to thrive, incapable of reading market signs and clocking suitable investments. There is the availability of more situations that clarify the position of an SME’s growth in the environment that has more to give and less to take. A good example is the West, where most Small owned businesses reach a revenue five times their initial starting point by the end of 2 years. In these situations, policies and strategies used for growth are very much different than the environments that have more to take than to give. Developing economies are the primary environment with such characteristics; a business started may not grow at all or remain at break-even for more than five years. SMEs with greater "internationalization" tend to report higher turnover and growth; these SMEs are more productive than their equivalent. However, in low-income countries, seven out of every ten new export relationships fail within two years. Only a minority of SMEs manage to sustain adequate growth patterns for a significant period. While SMEs are playing a vital role in the development process of countries, there is a scarcity of studies examining the issue of international competitiveness of SMEs. Therefore, this study fills this gap. The objective was to identify and explain the determinants of trade competitiveness of SMEs from developing economies, mainly from the agriculture sector, which is the central part of Tanzania's economy. One of the significant findings is that Government policies and regulations are not as strong as they should be and are not as enforced as they should be. The descriptive analysis also shows that a lot of the businesses involved in the agriculture sector owned privately. This situation shows the presence of a high percentage of companies that are registered and able to participate in the taxation system. The paper also lays out several challenges that SME’s face when they decide to go into business, common challenges were access to finance, unfair tax regimes, and lack of government support. The paper starts in chapter 2, which details a thorough literature review of SMEs and competitiveness — followed by Chapter 3, with an introduction to the history of SME development in Tanzania, which describes the development and definition of SMEs and Trade. Chapter 4 introduces the methodology perused int this paper, and Chapters 5 and 6 conclude the article is providing the significant findings, risks and challenges, and recommendations from the researcher.

2. Literature Review

- Until 2000, researchers around the globe used [1] Porter's model to analyze the international competitiveness of firms and economies; however, Porter had shortcomings when assessing the global perspective. [2] Chen & Lin; [3] Hitt et al.; [4] Moon & Lee indicated that while evaluating international competitiveness, not only a limited view but also the ability of local businesses to move abroad should be considered.In the context of developing countries, exports of the SME sector play a vital role in the country’s development process as it exemplifies the economic opportunities, as opposed to developed countries [5] Peña-Vinces et al. This paper supports this literature showing how developing country's economic structure, behavior, political and educational systems and level of industrialization differs from that of developed countries, findings based on studies of developed countries cannot always apply to the developing countries.The agriculture-based SME sector has potential, and consequently, efforts such as increased research & development, strategies, and should enforce schemes to build up the exportable agricultural products. Likewise, [6] Cerrato & Depperu firmly argued that competition amongst firms refers to the level of capacity of the firms to compete efficiently in both at home and abroad markets. Regarding the international competitiveness of firms, they used market share and performance in export to estimate general performance. On top of that, According to [7], Barney and [8] Fahy Resource-Based View (RBV) considers that all firms’ resources are not the same, and RBV plays a crucial role in determining firms’ international competitiveness because some resources of firms have a competitive advantage. [1] Porter considers a model that includes external features, industry-level. In addition to the recognition of the fact that developing countries, factors that involve institutions are much more critical, RBV depicts the significance of internal resources of firms [9] Welter & Smallbone. The RBV takes an ‘inside-out’ view or firm-specific perspective on why organizations succeed or fail in the marketplace [10] Dicksen. Resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable and cannot be substituted [7] Barney make it possible for businesses to develop and maintain competitive advantages, to utilize these resources and competitive advantages for superior performance [11] Collis and Montgomery; [12] Grant; [13] Wernerfelt.Since both internal and external factors may affect the competitiveness of an SME in a developing environment, researchers constructed a combination of both theories. An example, [14] Man et al., used four constructs of SME competitiveness external factors, internal factors, entrepreneur profile, and firm performance. In addition to the use of the RBV based determinants where external factors were operational as separated in industry conditions and government regulations, and internal factors, [15] Sirikrai and Tang measured monetary and non-monetary firm’s performance indicators in the assessment of international competitiveness.In the context of Chinese SME's competitiveness, [16] Yan proposed a model that includes strategic partnerships, innovation, and diversity strategies of firms and found that variables considered are significant. Determinants in different economies set to generalize how the firms operate with differing business and economic environments and therefore subject them to face different challenges. [17] Reddy et al. argued that the more government support provided to SME, the more the SME's international competitiveness would be. According to [18] Awuah and Amal, using data of less developed countries, the ability to internationalize their business occurs with firms that have innovative activities, exploit opportunities home and abroad, and face globalization challenges. [19] Siddik mentions that the highest innovation activities of SMEs were that they applied research and development findings to become internationally more competitive.Differentiation advantage can be connected to when a company provides higher value at the same cost or lower than competitors. These attributes to certain factors such as unique characteristics of a firm, product, or program that sets apart a firm from competitors in the view of the customer. All these factors can be attributed to the originality of a firm, causing SMEs to come through different, giving the ability to compete on a larger scale [20] Addai; [21] Arshad et al.; [22] Zeebaree and Siron, detected an impact that was positive on entrepreneurial orientation of firm performance; this implies that exporters must undertake risk while doing export business. They are arguing that to be competitive in international markets, SMEs are required to have characteristics of risk-taking, proactiveness, innovation, and competitiveness. Experienced firms are commonly known as those who are in business for more years, holding the ability to perform better than the firms that are at entry-level in the same industry. [23] Haenfler and Johnson discovered that older firms hold a competitive advantage in the export market than that of younger firms. They also discovered that the size of a firm in Turkey has a positive influence on competition and so concluded that larger firms are more likely to be productive exporters than smaller firms. However, according to [20] Addai, an internal process is more important than the environment. Suggesting that if SMEs do not organize their finances in terms of reducing costs, especially during periods of recession, they may not be able to pay their bills such as employee salaries, taxes, and supplies. Based on this assessment, recognize the internal process as a significant priority that companies which are SMEs must consider if they need to survive.The researchers above form a base for determinants needed to increase the competitiveness of an SME in a developing environment. Shedding light to both internal and external methods to which an SME can grow and become more competitive, allowing them to access trade competitiveness.

3. SMEs, Trade, And Development in Tanzania’s Agriculture Sector

3.1. Definition of SMEs

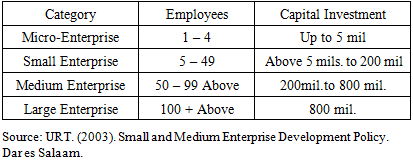

- Universally there is no one defined term for SME. SME is defined differently depending on countries and the level of development achieved. However, the generally used benchmarks in the definition include the total number of employees, the total investment, and profit. The Tanzanian Government defines SMEs according to the sector that it is in, the number of employees, and capital investment. Consequently, in the situation of Tanzania, SMEs are defined as micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises in sectors that include manufacturing, mining, commerce, and services. A microenterprise is defined as a firm with fewer than five employees, while a small enterprise is one with 5 to 49 employees. A medium enterprise is a firm with 50 to 99 employees and any enterprise with 100 employees or more regarded as a large enterprise. In a situation where an enterprise belongs to more than one category, then the level of investment is the deciding factor.

|

3.2. History of SMEs in Tanzania

- The SME sector is among the results of the failure of socialism, leading to the financial crisis that occurred in the 1970s and early 1980s, an outcome of the structural adjustment policy rather than of design. This political framework included the discouragement of the private sector in favor of public enterprises, which were government-owned, community-based, or cooperative owned ventures. Accordingly, the regulation restricted government employees from performing in any private business.Given that many of the educated people were members of the civil service, private businesses placed in the hands of the illiterate. Further, this African socialism policy based on the top-down approach in decision making; the Government made all the life conclusions for its citizen, including on matters such as who should go to which school or college, which should work, where one should work and live, how much one should earn in terms of wages. The reliance on Government discretion in decision-making decisions has resulted in a dependent society and wholehearted obedience among the Tanzanian people.This approach has contributed to the suppression of the development of entrepreneurial values such as the need for achievement, personal initiatives, and creativity, willingness to take risks and related behavior [24] Olomi. The socialism approach noted triumph in social development in the 1970s and early 1980s, mainly in fields like primary education, the delivery of health services as well as the water supply sector and sanitation [25] Temu and Due. However, the nationalization of the private sector-led to a weak economy marked by several imbalances on a macroeconomic level, and therefore, an economic crisis that lasted for over a decade [26] Kanaan. This downfall leads to a lower real purchasing power among the people who were in the workforce. Thus, it forced Tanzanian people to establish small businesses due to the increase of their hand-to-mouth earnings. For instance, some of the people began to involve themselves in activities that were unproductive such as dumping1. These kinds of businesses went against the government’s policies that deemed such businesses as being against the country’s philosophy [27] Maliyamkono and Bagachwa.Succumbing to pressure and influence from the outside world, the Tanzanian Government changed its policy from a state-led economy to a market-driven economy. The final transformation happened in 1991, leading to the privatization of most public enterprises. The privatization of government-owned enterprises and the withdrawal of the government from activities resulted in the reduction of expenditure on workers from the public sector. They resulted in turning to micro-enterprises for survival. The SME sector has now become highly invested in the sector of the government of Tanzania, with significant agendas planned to lift its economy. Indeed, the SME sector has an important role to play in income and employment generation. Having explained the development of the SME sector in Tanzania, the section below defines SME according to Tanzanian definition; this follows a review of the current status of SMEs in Tanzania.

3.3. Current SME Sector Situation in Tanzania

- However, the critical role played by the SME sector in economic development; it is problematic to attain recent and reliable data concerning the current status of the SME sector in Tanzania. From the interviews conducted by the researcher in the current study, it has discovered that micro and small enterprises control the SME sector despite the availability of data to support the context. Additionally, according to [28] Essays, UK, there are an estimated 2.7 million enterprises in the country, out of which about 60% located in the urban areas. The bulk of these enterprises are micro (employing less than five people). They are showing a lack of the presence of middle and large enterprises. Most of the micro and small enterprises have an annual turnover of less than US $2,000 and have established a survival strategy. Moreover, there are estimated to be more than 3 million SMEs (de facto MSMEs) with over 5.2 million employees in Tanzania of which some 45% located in urban and the remainder in rural areas; the industrial sector encompasses some 25,000 enterprises, 97% of which have ten employees or less (compared to 40 large manufacturing enterprises with 500+ employees, covering about one-third of employment in the industry) [29] SME Development Policy.The review of the SME policy also shows that a large proportion of businesses are considered informal; the size of the informal economy has decreased over time. In terms of the percentage of GDP: from 62.5% in 1991 to 43.6% in 2005 and 39.7% in 2010; the estimated size of the informal sector as a percentage of GDP excluding agriculture is smaller and moved from 43.1% in 1991 to 30.1% in 2010 and 27.4% in 2010 (showing a gradual trend from informal to formal).Many measures have been taken by the government to increase the potentiality of SMEs in the country. For example, In December 2016, the African Development Bank (ADB) authorized a Line of Credit (LOC) of an estimated USD120m to Tanzania to finance infrastructure and SME projects. The LOC allocated to the largest commercial bank in Tanzania, CRDB, which supports various sectors of the government such as electricity, industry, agriculture, and SMEs. By capitalizing on the CRDB’s branch network and agents, the Letter of Credit will increase lending to SMEs and businesses owned by women in both urban and rural areas to create more jobs and to promote inclusive growth for Tanzania’s economy, the ADB indicates. Furthermore, In September 2016, Tanzania officially launched the Tanzania Entrepreneurship and Competitiveness Centre (TECC) to promote entrepreneurial innovation and competitiveness in the country. Since then, TECC has collaborated with various institutions to promote local economic development, enhance skills development in entrepreneurship innovation and competitiveness, and providing business intelligence through studies and advisory services. For example, in April 2019 TECC and Tanzania Chamber of Commerce Industry and Agriculture (TCCIA) during the week of the launch of the 6th Via “Jiandalie Ajira”2 which runs for three months, organized a training camp by experts and mentors on entrepreneurship for the youth which targeted 400 youths aged between 18 and 24.

3.4. SME Contribution to Development in the Agriculture Sector

- The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Tanzania was worth 57.44 billion US dollars in 2018. The GDP value of Tanzania represents 0.09 percent of the world economy. GDP From Agriculture in Tanzania decreased to 8,033,694.74 TZS Million in the second quarter of 2019 from 8,187,833.59 TZS Million in the first quarter of 2019. In 2018 there was 66.35 percent of the population employed in agriculture, 7.07 percent in industry, and 26.58 percent in the service sector. Agriculture still holding the highest percent of employment in the country, holding its position as the backbone of the country. There is an estimate of Tanzania’s SME sector consisting of above 3 million enterprises contributing to an overall of 27% of the GDP. The majority involved in the agricultural sector, and ironically women own more than half of the enterprises established. Conclusively, the investment of SME businesses is one of the most effective ways of poverty alleviation and income creation. Agriculture employs about three-quarters of the country’s labor force, with the limited transformation (agriculture accounts for less than one-third of GDP). The sector dominated by subsistence farming, small average plot sizes, and limited mechanization. Market opportunities for staple and cash crops controlled by poor infrastructure. SMEs play a key role in bringing about the needed reinforcement of agriculture-industry linkages. Their contribution is relevant in multiple fields, from the modernization of agricultural production to the increase in agricultural productivity, the local processing of agricultural produce/commodities as well as to the creation of off-farm employment opportunities. Elevating SMEs to the center of industrial development and economic growth requires financial and human resources (training) to achieve their goals. The government must encourage SMEs to expand and to evolve, innovate, hire employees, and inspire others to do the same. The benefits of the Tanzanian economy would be enormous.

4. Methodology

- This chapter explains the approach used in this study and how it carried out. It highlights the choice and mode of operation, as well as techniques used in data analysis. It describes the sampling technique or procedure and states the main methods used in data collection from the field.A research methodology is a way to solve the research problem systematically. In it, the study of several steps that are usually adopted by a researcher in pursing research challenges and the logic behind them is discovered [30] Kothari. The next sections of this chapter demonstrate the systematic way in which this study was conducted.

4.1. Research Design

- A research design is simply the framework or plan for a study used as a guide in collecting and analyzing data. According to [31] Adam and Kamuzora, a research design understood as a detailed work plan which, when used to guide a research study to achieve specified objectives of the research.This paper used a combination of theory and econometric analysis; this method adopted to determine the phenomenon of determinants that enhance the trade competitiveness in Tanzania’s agricultural sector. The central approach of data collection involved questionnaires that targeted the exploration of the determinants provided by the theoretical perspective of competitiveness in trade.An empirical investigation was done by [32] Pandula involving factors such as experience, education, firms performance, sectors, tangible assets, financial auditing, location of the firm, age of the firm, size of the firm, membership association, the results indicated that education of the entrepreneur and having membership with business associations are associated with access to bank finance.[33] Abdilahi and Hassan's study examined the impact of innovation on the performance of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Hargeisa, Somaliland. A sample of 378 SMEs has drawn from a population of 6930 SMEs. Their study adopted both descriptive analysis and regression analysis to estimate the impact of innovation.

4.2. Data Collection Methods

- This paper uses both primary and secondary methods of data collection. Primary data is the type of data collected in the field of study for answering research questions. Primary data collected through observation, direct communication with respondents, or through personal interviews. They may also gather information through interviews and questionnaires [34] Kothari. Questionnaires are an ideal tool when trying to achieve a high return rate, and it often works particularly well in combination with interviews. It allows for questionnaire data to flesh out with great depth and detail [35] Lambert. In this study, the primary data collected through questionnaire questions adapted from a survey run by the Ministry of Industry and Trade in Tanzania called the ‘National Baseline Survey Report for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises in Tanzania’ (December 2012). a. InterviewsInterviews defined as face to face contact between interviewer and interviewee. It can take place at any location, depending on the nature of respondents.In this study, this method employed to gather information on the respondents’ views on the topic under study. It used multiple ended questions, which asked accordingly. The interviews conducted at random with a few key players in the agriculture community.The interview questions were like the open-ended questions found in the questionnaires. Still, it allowed for space to answer in a more in-depth perspective, with follow up unstructured questions to understand better.b. QuestionnairesQuestionnaires defined as a research instrument consisting of a series of questions (or other types of prompts) to gather information from respondents.In this study, the questions picked from a series of questions from a survey held by the Ministry of Industry and Trade in Tanzania called the ‘National Baseline Survey Report for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises in Tanzania.’ The questions that picked were relevant to the study and could adapt to the agricultural sector.Through this tool, the respondents were able to answer the questions concerning the study. During the study, the questionnaire administered by the researcher, and the respondents required to fill them under her guidance. The questionnaires were of two main types: closed and open-ended ones.

4.3. Selection Criteria

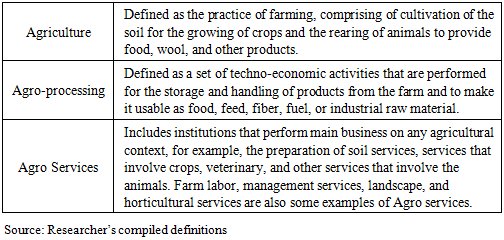

- This paper has adopted the most traditional way of describing the internationalization process which involves four key stages: (i) direct exports to a foreign country; (ii) exporting with the help of independent foreign agents; (iii) the use of subsidiaries to carry out this function; and (iv) the establishment of production facilities in the said export market.The main interest of this paper is of SMEs that are Agribusinesses. Agribusiness involves all activities that involve agricultural food and natural resources used to produce food and fiber. Agribusinesses that performed solely may take part in selling items to farmers for production, providing services to other agricultural businesses, or engaging in the marketing, transportation, processing, and distribution of agricultural products.Agriculture goods incorporate vegetables and fruits, potato, tea, tobacco, meat, and the like. Processed food that is ready-made using products from the farm like spices, rice, puffed rice, juice, canned food, and others alike are the agro-based processed food. This paper adopted the following criteria to serve the purpose of the study; the sample includes:i) The firm must be small or medium-sized to adhere to the definition of SMEs as put forward by the Tanzanian government. ii) If the firm is involved in exporting, it must have a minimum of five years of experience, including domestic market experience. The researcher selected SME’s from various regions in Tanzania, due to the paper being agriculture-based businesses, most of them were in the rural areas of the country. The SME’s are grouped according to their type of business, as explained below:

|

4.4. Data Analysis Framework

- All data collected were organized and checked before they presented and analyzed to ensure completeness, accuracy, and validity. By completeness, it means all questionnaires checked to see whether all questions are answered and handed over. By validity, data checked in terms of time reported and if they conform to the objectives of the study. Discussion and Analysis did the following percentage and occurrences generated and interpreted accordingly. Qualitative data analysis involved the reduction of accumulated data to a manageable size, developing summaries, and looking for patterns. It also includes the interpretation of research findings considering the research questions. Most of this data from interviews were analyzed interpretively.Quantitative data collected through questionnaires that were processed using the statistical package for social science (SPSS). The results of the study presented in tables, percentage charts, and graphs below. Therefore, both qualitative and quantitative methods of data analysis used for the study.

5. Study Findings and Results

- This chapter showcases the data collected for the study, and the analysis runs on the data and discussion of the results obtained. The data concerning factors determining the competitiveness of SMEs involved in the agricultural sector in Tanzania collected through various methods, namely: questionnaire, open and closed-ended interview. The data collected covered regions across Tanzania. However, before the presentation, analysis, and discussion of the empirical findings, there will be an outline of the different aspects of respondents according to the variables used in the study. They are also analyzed since they are among the ways which establish validity and reliability of the data collected. Shown below are findings, analysis, and discussion presented in the context of aspects of the respondents and findings as per the study objectives.

5.1. Respondent Profiles

- This part will lay down a foundation of profiles for the respondents in correspondence to the variables collected to understand some of the aspects drawn from the data collected. It provides a brief description of some demographic characteristics of the sampled respondents, specifically gender and education. Going-over these characteristics of individuals not only helps the accuracy of the data but also provides a look at trends in these characteristics over time; most importantly, it provides the basis for the analysis of the way these characteristics were related to most of the other issues investigated in this study.

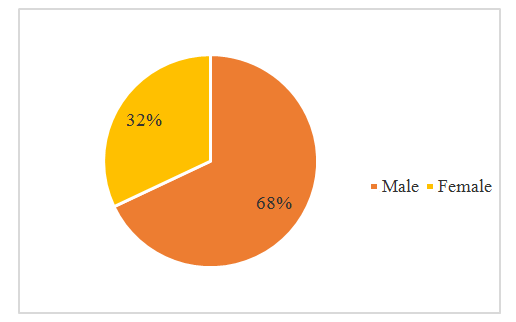

5.1.1. Gender

- According to the response from the sample, the following was the division of genders:

| Figure 5.1. Distribution of Gender (Source: Questionnaires distributed by the researcher 2019) |

5.1.2. Education Level

- According to the response from the sample, the following was the division of level of formal Education:

|

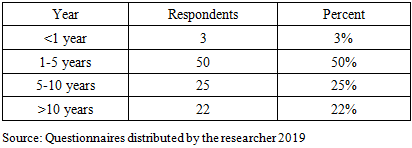

5.1.3. Years in Business

- According to the response from the sample, the following was the division of the number of years the respondents have been in business:

|

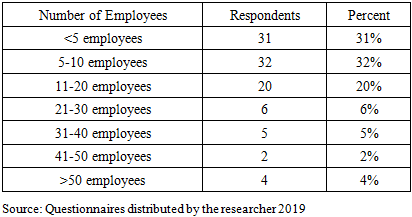

5.1.4. Number of Employees

- According to the response from the sample, the following was the division of employees:

|

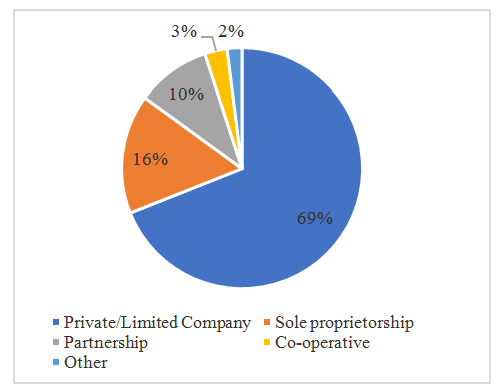

5.1.5. Legal Ownership of The Business

- According to the response from the sample, the following was the division of the legal ownership the respondents have in business:

| Figure 5.2. Distribution of division of legal ownership (Source: Questionnaires distributed by the researcher 2019) |

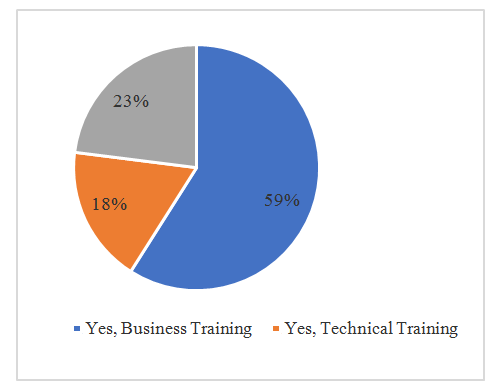

5.1.6. Relevant Training Skills

- According to the response from the sample, the following was the division of relevant skills acquired by the respondents in the business:The findings show that out of 100 respondents, about 76 (76%) of them had relevant training for their businesses. Business training includes various business training programs, for example, advertising and marketing courses, business management courses, and money management courses — these types of training given by different private and public organizations throughout the country. Technical training, in this case, can be training programs in their sectors that teach a skill. Agricultural or agro-processing training programs are set up by different government arms like Small Industries Development Organization (SIDO) and Tanzania Horticultural Association (TAHA).

| Figure 5.3. Distribution of Relevant Training Skills (Source: Questionnaires distributed by the researcher 2019) |

5.2. Empirical Findings

- Adapting suggestions from the resource-based view of the firm (RBV), which considers the internal perspective of the firm, and [36] Porter’s, which takes the external perspective. To increase competitiveness in a developing environment, SMEs need to apply both external determinants like government policy and internal determinants such as skilled labor and capital.From the above speculations, the following hypotheses formulated: H1- Government support for SMEs has a positive influence on the trade competitiveness of SMEs. [37] Zindiye et al. observed that government policies and support factors play a decisive role in improving SMEs ' competitiveness.H2- Level of education has a positive effect on SME business competitiveness [38] Setyawan observed that the level of education in the SME industry is related to the ability to conduct business plan and risk determination in the business. Human resource plays an essential role in building competitiveness.H3- Access to finance has a positive effect on SME business competitiveness. [39] Abor et al. observed that more and easier access to finance leads to the improved export performance of SMEs.H4- The size of the firm has a positive influence on SME competitiveness. The bigger the size of the firm, the more competitive it becomes due to the increase in production and effectiveness.H5- The number of years that a firm has been in business has a positive influence on SME business competitiveness. The more time in the business, the more connections and experience acquired as opposed to a starting firm.H6- Revenue has a positive effect on SME business competitiveness. The presence of a high income shows a high probability of the business to handle the higher competition.

5.2.1. Variable Measurement

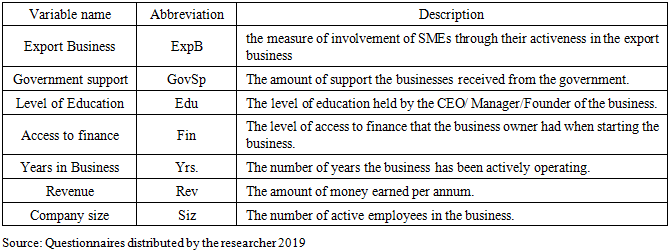

- Since the primary purpose of this study is to identify the determinants of SMEs' competitiveness, the dependent variable is SMEs' competitiveness in trade, which will be measured by SMEs involvement in export business (ExpB). Adapting the work of [40] Appiah et al. and [41] Mittelstaedt et al., the measure of involvement of SMEs through their activeness in the export business. SME activeness in export business will take a value of 1, otherwise 0. The following table summarizes independent variables considered in the model:

|

5.2.2. Model Estimation

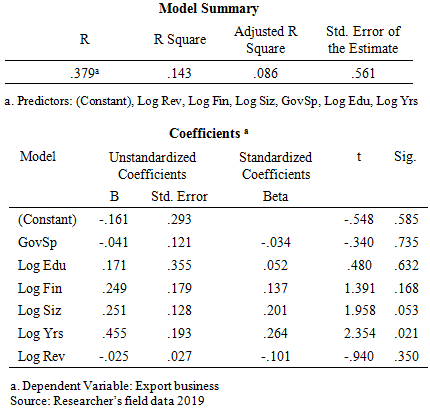

- The researcher developed a linear regression model to estimate the effects of government support, level of education, access to finance, years in business, revenue, and company size to export business. Equation 1, following the work of [41] Appiah et al., below is the adopted and proposed regression model:ExpB = β0+β1GovSp+ β2 LogEdu+ β3 LogFin +β4 LogSiz+ β5 LogYrs+ β6 LogRev+ e1

5.2.3. Data Analysis

- The following is a table showing results run in the linear regression run in SPSS:

The estimated equation becomes:ExpB = - 0.161- 0.034GovSp + .052 LogEdu + 0.137LogFin + 0.201LogSiz + 0.264 LogYrs - 0.101LogRev + e1Interpreting the data per the provided hypothesis:H1- Government support for SMEs has a positive influence on the trade competitiveness of SMEs. The statistical data shows a negative coefficient (-0.034) associated with Government support. It shows that contrary to the hypothesis, the presence of government support does not prove to have a positive effect on competitiveness statistically. It affects the presence of competitiveness at a 3.4% rate; hence it is not a highly significant factor that determines the presence of competitiveness. It may also imply that the presence of a lack of enforced government policies and regulations have become a common factor in Tanzania.H2- Level of education has a positive effect on SME business competitiveness.Statistically, the level of education shows to have a positive effect (0.052) on the presence of SME competitiveness. It implies that the higher the level of education of people involved in the firms, the higher levels of the presence of competitiveness. The effect rate that level of education has on competitiveness is 5.2%, which is not a significant factor but affects the presence of competitiveness in a firm.H3- Access to finance has a positive effect on SME business competitiveness. The data on access to finance measured the rate at which it was easy or difficult to access finance, and it used a scale of 1-10, 1 being difficult, and ten is easy. Statically the data appears to support the hypothesis, claiming that if the access to capital and finance throughout the process of starting, running, and maintaining an SME is more comfortable, the easier it is to stay competitive and grow. The coefficient (0.137) suggests that access to finance affects competitiveness at a rate of 13.7%, which may imply. However, there is a small presence of banks, microfinance institutions, and government arms that provide these services, and their presence is minimal. H4- The size of the firm has a positive influence on SME competitiveness.This hypothesis does support the notion that bigger sized firms are more likely to be more competitive in the market; the significance of the size of the firm is at 20.1% (0.201). It may imply that for the case of Tanzania, both small and medium firms have the chance to participate in market competition. However, it may also imply that there is a lack of presence of small and medium firms in the international market.H5- The number of years that a firm has been in business has a positive influence on SME business competitiveness.The statistical data supports the hypothesis of the longevity of a firm that supports the firm's competitive edge. This positive presence implies that a long-termed business through small or medium can compete in a large-scale market. The experience and connections gained from longevity can be one of the reasons this makes it possible. The rate that it affects competitiveness (0.264) is moderate and the highest factor in our pool.H6- Revenue has a positive effect on SME business competitiveness.The presence of high revenue appears to have an opposite reaction to the presence of competitiveness, contradicting the hypothesis stated above. It could mean that the presence of revenue does not necessarily mean that the business is profiting and competing at the level that it should be competing. It also shows a lack of investment in innovative means to increase the productivity and effectiveness of the business, causing no presence in the competition.

The estimated equation becomes:ExpB = - 0.161- 0.034GovSp + .052 LogEdu + 0.137LogFin + 0.201LogSiz + 0.264 LogYrs - 0.101LogRev + e1Interpreting the data per the provided hypothesis:H1- Government support for SMEs has a positive influence on the trade competitiveness of SMEs. The statistical data shows a negative coefficient (-0.034) associated with Government support. It shows that contrary to the hypothesis, the presence of government support does not prove to have a positive effect on competitiveness statistically. It affects the presence of competitiveness at a 3.4% rate; hence it is not a highly significant factor that determines the presence of competitiveness. It may also imply that the presence of a lack of enforced government policies and regulations have become a common factor in Tanzania.H2- Level of education has a positive effect on SME business competitiveness.Statistically, the level of education shows to have a positive effect (0.052) on the presence of SME competitiveness. It implies that the higher the level of education of people involved in the firms, the higher levels of the presence of competitiveness. The effect rate that level of education has on competitiveness is 5.2%, which is not a significant factor but affects the presence of competitiveness in a firm.H3- Access to finance has a positive effect on SME business competitiveness. The data on access to finance measured the rate at which it was easy or difficult to access finance, and it used a scale of 1-10, 1 being difficult, and ten is easy. Statically the data appears to support the hypothesis, claiming that if the access to capital and finance throughout the process of starting, running, and maintaining an SME is more comfortable, the easier it is to stay competitive and grow. The coefficient (0.137) suggests that access to finance affects competitiveness at a rate of 13.7%, which may imply. However, there is a small presence of banks, microfinance institutions, and government arms that provide these services, and their presence is minimal. H4- The size of the firm has a positive influence on SME competitiveness.This hypothesis does support the notion that bigger sized firms are more likely to be more competitive in the market; the significance of the size of the firm is at 20.1% (0.201). It may imply that for the case of Tanzania, both small and medium firms have the chance to participate in market competition. However, it may also imply that there is a lack of presence of small and medium firms in the international market.H5- The number of years that a firm has been in business has a positive influence on SME business competitiveness.The statistical data supports the hypothesis of the longevity of a firm that supports the firm's competitive edge. This positive presence implies that a long-termed business through small or medium can compete in a large-scale market. The experience and connections gained from longevity can be one of the reasons this makes it possible. The rate that it affects competitiveness (0.264) is moderate and the highest factor in our pool.H6- Revenue has a positive effect on SME business competitiveness.The presence of high revenue appears to have an opposite reaction to the presence of competitiveness, contradicting the hypothesis stated above. It could mean that the presence of revenue does not necessarily mean that the business is profiting and competing at the level that it should be competing. It also shows a lack of investment in innovative means to increase the productivity and effectiveness of the business, causing no presence in the competition.6. Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations

- This chapter provides a summary of the significant findings, conclusion, and recommendations concerning the stated purpose. It also gives suggestions on areas for further studies. The purpose of this study was to evaluate determinates that promote competitiveness in SMEs in the agricultural sector in Tanzania. It targeted the determinants of SME competitiveness in a developing environment, specifically, for the agricultural sector. It outlines ways in which a small business can achieve profitable growth and highlight the risks and challenges that accompany the expansion of a business, i.e., providing reasons why a business cannot or rather does not grow from small to medium in Tanzania.

6.1. Summary of Major findings

- With the collected data, we can see major determinants that are supposed to play a role in the aggressive growth of a firm, according to most of the theoretical frameworks, which are close to insignificant in this case. Thus, showing how determinants used in the developed economies not applied to the developing economies.One of the significant findings is that Government policies and regulations are not as strong as they should be and are not as enforced as they should be. Some programs and policies are being made by the government to help the growth of small and medium enterprises, but the enforcement of the policies is still feeble.Another significant finding is the negative correlation between revenue and competitiveness. The presence of the negative relationship between the gaining of revenue and competition could mean that although the SME’s are in business and gain a substantial amount of revenue a year, there is no investment in innovation and research into how they can be better in terms of business and production. It shows that many business owners perform a hand to mouth form of business and have minimal interest in the expansion of their business.There is a positive relationship between the level of education and competition. This confirms the assumption that having an educational background brings an added advantage to the aspect of competition. Being able to think critically, solve problems quickly, read, write, and perform pure mathematics can lift the business into a higher competitive field.From the descriptive analysis, we see that most SME’s are dominantly male-owned/run and have training in either business or technical skills. Organizations like SIDO, TAFOPA, and CEED play a significant role in training entrepreneurs in both technical and business and are useful tools into a path to starting entrepreneurship ventures.The descriptive analysis also shows that a lot of the businesses involved in the agriculture sector are in the private sector. It shows the presence of a high percentage of companies that are registered. Realistically Tanzania being a developing country, has many unregistered and informal businesses that run their businesses at a micro-level; however, this shows that there is an improving number of businesses that are now branching into small and medium enterprises.

6.2. Risks and Challenges

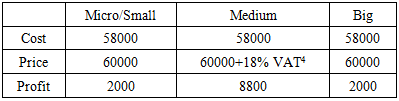

- Finance holds a significant part of the challenges faced by SME’s in Tanzania. Access to finance from microfinance institutions and banks is a significant way to gain capital for SME’s in the country; however, the loan policies enforced, and bank systems are flawed. In terms of provision of capital, collateral laws, and policies associated with co-financing, if another bank wants to buy off loans.If the focus is on small businesses, these businesses lack the presence of a proper management team, in terms of human resources and accounting services. Accompanying this is the presence of unfair tax policies towards businesses that are small/micro, leading to the presence of more informal (unregistered) businesses. The presence of a lot of informal enterprises raises a challenge; while more than one-quarter of the world’s arable land lies in Africa, it generates only 10 percent of global agricultural output. Despite the considerable potential for growth in this sector, most of the businesses have mainly remained informal, thereby limiting the sector’s contribution to the growth of the economy.Other barriers that hold SMEs back from growing are the lack of appropriate skills, knowledge, technology, and limited access to markets. Provision of this form of education to the initial farmers, all the way to the processors and the business owners, Mentink emphasized: “Addressing these constraints is crucial to moving towards sustainable employment, innovation and increase incomes and -exports in Tanzania.”When a business manages to handle the initial challenges and grow from small to medium, the challenges that follow them are higher interest rates from banks or microfinance institutions. There is an increase in distribution and production costs. Just like small businesses, the presence of tax regulations is a considerable constraint for businesses of this level too.Below is an example provided by one of the interviewees that is an active member of the agricultural sector and currently serves as the Director of SMEs in Agro processors in the Singida region, Tanzania. To give a perspective of the tax challenge in Tanzania, he gave a picture of three companies that produce oil:

|

6.3. Recommendations and Shortcomings

6.3.1. Recommendations

- The government should place new tax regulations that favor SME’s as opposed to killing them. Agriculture is the largest sector in Tanzania, and the lack of favorable tax regimes defeats the purpose of it being the backbone of the country. The majority opt to go into an agricultural sectored business based on the high demand for the goods produced from this sector; having regimes that guarantee success would be one way of increasing competition.Local governments should provide tax exemptions to unnecessary codes and payments on the production process. The presence of these codes and payments increases the production costs of the business, and this increases the price that then increases the business’s tax bracket. Most of the fees charged are unnecessary and unfair to businesses that have just gotten their feet off the ground and do not have enough capital to cover extra costs.Any imported agricultural-related product should be assigned higher tariffs. It will help promote local products to have the upper hand in the market and will also allow the businesses to grow in competitiveness in the country and abroad.Government intervention through reviving of old industries throughout the country is among some of the projects that will assist the increase of production and opportunity. The project has mainly focused on Nyerere industries around the country. Still, there are so many other private old industries that could be acquired and invested in increasing that presence of competition, and this would provide resources to small businesses.Banks, microfinance institutions and other related organizations should give a fair amount of time for the SME’s to grow and expand in production before being required to pay back their loans and debts. Realistically the growth of an SME is slow and depends on so many individual factors, and each business has its unique time of growth. These institutions should cater to the needs of each business, explicitly providing it with the appropriate time to rebound and gain profit.Institutions like SIDO and TAHA need to increase the frequency and quality of their educational services to include the countryside to serve farmers. These educational seminars will assist in the refinement of services provided by the business and help increase sales and business ventures. Also, there is a need to refine their services, to include the assessment of the SME’s every term to allow a fair process towards their subsidies program. These assessments should be divided by size and capacity to allow precise and adjustable cut off-limits. It will allow the institutions to be more organized and know how many businesses are in each category while providing a fair subsidy system that allows space for a business to grow competitively before having to worry about extra costs.The ministry of industry and trade should perform annual assessments of businesses in the country to know the real-time situations and problems that the businesses are facing and asses industry environments to know what areas to work on and improve. It will also provide a perspective on how far they have gone and advanced the sector accordingly.Formation of industrial parks. It is the collection of all agriculture and agro-processors businesses in one area to share technology, knowledge, and resources (raw material). The businesses can enjoy the benefit of reduced production costs due to the availability of skilled labor, the presence of repair and maintenance services, availability of components, and the presence of financial institutions. They can benefit from inter-relatedness, and the initial investment would below.There should be the presence of inclusive value chains in the countries agricultural sector, and this will help the generation of economic growth and Tanzania’s agriculture productivity. Reevaluation of the whole value chain and there should be the creation of more lucrative market linkages. This inclusiveness needs to begin from the inputs through harvest, marketing processing, and selling. It benefits all parties involved from farmer to consumer.SMEs should make sure they have disciplined financial management, differentiating products and services to satisfy customer needs, having a business located within reach of their customers, and excellent networking can make a difference between succeeding and failing.

6.3.2. Shortcomings

- In the process of conducting research, expected that the points of competitiveness studied, and their impact will provide a better understanding of this crucial concept. The challenge is an established study such as this can only make a modest contribution. Space for larger samples to be acquired was available; however, limited due to the nature of the study and the resources available. Access to the data was limited based on the availability of information from the different headquarters, access to the management, and staff. The researcher also gave results based on returned questionnaires. There may include information that companies will not disclose because of its confidentiality and a negative culture in the country towards questionnaires and interviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to recognize my supervisor Ms. Zong Yijun of the School of Economics at Shanghai University. The door to Prof. Zong's office was always open whenever I ran into a trouble spot or had questions about my research. She consistently allowed this paper to be my work but steered me in the right direction whenever she thought I needed it.I want to give thanks to the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH) for providing the research permit needed to conduct this research in the country. I would also like to thank the experts who were involved in the collection of the data for this research project: The Tanzania Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture (TCCIA); Tanzania Agricultural Association (TAHA); Tanzania Bureau of Standards (TBS); United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and The Center for Entrepreneurship and Executive Development (CEED). Without their passionate participation and input, the primary data set collected could not have been successfully conducted.Finally, my very profound gratitude to God, my parents, and my sister, for providing me with unfailing support and encouragement throughout my years of study, Thank you. This accomplishment would have been impossible to achieve without them. Thank you.

Notes

- 1. Smuggling goods from neighboring countries and sold them for higher prices2. Jiandalie Ajira- Prepare yourself for employment.3. Technical training involves any certification courses and diplomas.4. A value-added tax (VAT) is a placed on a product whenever value is added at each stage of the supply chain, from production to the point of sale.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML