-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2020; 10(3): 138-148

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20201003.04

Transportation Management Challenges in Ghana: A Study of Three Selected Companies in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis

Daniel Odoom1, Christian Kyeremeh2, Kwame Owusu-Ansah Owusu Afram3, Stephen Tawiah4

1Graduate School, Ghana Technology University College, Takoradi Campus, Ghana

2School of Business and Management Studies, Sunyani Technical University, Ghana

3Directorate of Human Resources and Organizational Development, Ghana Technology University College, Accra, Ghana

4GCB Bank, Takoradi branch, Ghana

Correspondence to: Daniel Odoom, Graduate School, Ghana Technology University College, Takoradi Campus, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Effective transport systems are critical in the socio-economic development of nations. Globally, there is a wide recognition of the need to put in place adequate measures to achieve sustainable transport systems for the greater good of society. To do this, requires an awareness of the myriad of challenges faced by stakeholders in the transport sector. Against this background, the researchers sought to explore the transportation challenges companies in Ghana face using Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis (STM) as a case. The study adopted the mixed methods approach with descriptive survey as the design. A total of 85 employees of three companies in the Metropolis was involved in the study through census data collection method. The research instruments used were questionnaire and interview guide whilst percentages, means, standard deviation and thematic analytical tools were employed for the study. The study discovered that the greatest transport management challenge in the Metropolis is the general lack of transport management experts. Other challenges include high cost of transport operations, poor vehicle maintenance, ineffective transport policies in organizations and weak transport infrastructure in the Metropolis. It is recommended that companies in STM should put in place proper training and development programs to address the skill gaps in inherent in their transport management systems.

Keywords: Transport, Transportation management, Challenges, Supply chain, Logistics

Cite this paper: Daniel Odoom, Christian Kyeremeh, Kwame Owusu-Ansah Owusu Afram, Stephen Tawiah, Transportation Management Challenges in Ghana: A Study of Three Selected Companies in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 10 No. 3, 2020, pp. 138-148. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201003.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- While development programs and policies tend to pay increased attention to physical capital, there has been an increasing recognition of the need for a proper balance through the inclusion of human capital issues. Despite the relative importance of human and physical capital, development cannot take place without both interacting since infrastructures cannot become effective without proper operations and maintenance. Likewise, economic activities cannot occur without a sound infrastructure base. The vastly transactional and service-oriented roles of transport sector highlight the complex relationship which exists between its physical and human capital needs (Rodrigue and Notteboom) [1].Transportation has been described as the movement of animals, goods and persons from one place to another. Transportation is one of the oldest forms of human activities whose origin can be traced to the early days of creation. Men and animals, since creation, have moved from place to place for various reasons. Development of human civilization has resulted in a corresponding development in transportation (Stock and Lambert) [2]. Currently, there are several modes of transportation which can be employed by men for their movements as well as movement of goods and services from place to place. These forms of transport have been classified mainly into five namely: air, rail, road, water, and cable. Each of these forms of transport has its own advantages and disadvantages. However, the choice of a transport mode depends on such factors as quantity of cargo, nature of cargo, destination of cargo and expected time of arrival of the cargo. For example, water transport, especially maritime transport, has been identified as an efficient and effective means of moving very large quantities of bulk cargos from one continent to the other. Again, the delivery of perishable goods in a relatively shorter period of time will require the use of air transport while most inland movements of goods make use of land transports such as road and rail transport (Fair et al.) [3].According to Tseng, Yue and Taylor [4], the supply chain of any organizations can be broadly divided into three activities namely: purchasing, manufacturing, and transport. Transportation helps to connect the other two operations of supply chain management. Also, transportation ensures that decisions relating to materials to use, inventory levels, distribution network configuration, and production quantities are effectively carried out (Tseng et al.) [4]. In fact, international trade and globalization have been made possible in the world today due to the existence of efficient and effective transport systems in many nations. As a result, today’s businesses and organizations have been given opportunities to achieve increased performances with improved transport systems as one critical tool (Stopford) [5]. The role of transportation in today’s business management goes beyond the tradition definition of movement of animals, goods and persons. Essentially, transport management has now become a potent tool for competitive advantage. Thus, businesses are able to achieve a reduced cost of operation, increased customer satisfaction and loyalty by means of an improved and efficient transport management. Besides, suppliers of raw materials, producers and distributors of products cannot perform as expected without an effective transport system (Taniguchi and Thompson [6]; Tawiah [7]). As a concept, transport management involves the process of planning, implementing, and controlling all the activities required for the movement of goods from one place to another. It is an activity which requires the input of several stakeholders. For example, an effective transport management in organizations requires the input of maintenance personnel, fleet planning officers and drivers. Each stakeholder in transport management plays a unique role that combine to result in an effective transport management (Younkin, as cited in Tawiah [7]. The over-arching goal of any transport management activities in organizations is to ensure that there is improved organizational performance. To achieve this requires effective transport management practices in areas such as carrier management, load planning and optimization, shipments, freight payment, among others (Liviu and Emil) [8]. Transport accounts for as much as 30% of the total cost of logistics operations which is almost as much as warehousing and inventory management cost put together. This heightens the need for an economic transport network to promote an effective management of the cost associated with the movement of goods and persons in business organizations (Tawiah) [7]. The transport sector in Ghana accounts for more than 80% of the movement of goods and persons on daily basis. Despite the strong dominance of the road sector in Ghana, other modes of transport such as air, railway and inland water transport also play significant role in the economic development of the nation (Aghazadeh [9]; Tawiah [7]). The Government of Ghana largely owns and operates railway and inland water transport in the nation while private individuals almost completely dominate the air transport industry. With regard to the road transport sector, both public and private own and control it though private entities and individuals own the largest share of fleet on the roads in Ghana (Osei and Kumah [10]; Tawiah) [7].Generally, the transport sector in Ghana is characterized by a limited regulatory and institutional effectiveness and lack of a clear and comprehensive policy. In particular, although the road sector is the dominant transport sector, there are no standard regulations on area of coverage, standards of operation, maintenance of vehicles and related emissions. This has resulted in an industry which is characterized by no entrance and exit restrictions resulting in unreliable, uncomfortable and unsafe services (Aghazadeh [9]; Tawiah) [7]. Finance is a limiting factor due to the capital intensive nature of public transport operations. Financing of vehicles in the Ghanaian road transport industry is left completely in the hands of the individuals who have the ability to raise the needed capital to afford vehicles. There is also the problem of foreign exchange which affects transport management in Ghana. The cost of most transport inputs including fuel, spare parts and tyres are all tied with foreign exchange rate (Tawiah) [7]. This means that an increase in the rate of current exchange results in increases in prices of these items, hence increased cost of transporting goods and persons in the nation. What is more, the prevailing situation has made it very difficult for transport owners in the nation to easily replace vehicles or vehicle parts which have outlived their usefulness. Therefore, vehicles get older, cost of operations and maintenance soar up, eventually operations grind to a halt (Osei and Kumah [10]; Tawiah) [7]. In spite of the enormous contributions of transport management to organizational performance and the overall economy, Stopford [5] and Tawiah [7] maintain that the sector is faced with several challenges. Stopford [5] further identifies truck break down, over carriage and short landing as some of the transport management challenges affecting businesses and organizations around the globe. According to Stopford [5], most businesses and organizations encounter various forms of challenges with respect to their transportation operations which hamper smooth organizational goal attainment. The Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis (STM) is one of the areas of Ghana facing various forms of transport management challenges which affect their performance. However, literature on the subject of transport management challenges among businesses within the Metropolis is sparse (Tawiah) [7], hence this study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Concept of Transportation

- As a term, transportation has received different conceptualizations among scholars. For example, Chopra and Meindl [11] defined transportation as the movement of goods and persons from one location to another in a supply chain. This definition points to the basic function of transport operations which is to enable goods and persons to be able to move from one point to another. Webster [12] also sees transportation as a commercial activity whose focus is on conveying persons and goods from one place to another. Clearly, Webster’s definition goes beyond the basic function of transport which is conveyance of goods and persons to indicate that transportation is a commercial enterprise or operation. Carter and Price, as cited in Tawiah [7] go a step further from that of Webster by highlighting the product of transport operation as a commercial activity. The authors described transport operations as a commercial enterprise whose product is the safe, secure and timely delivery or conveyance of goods and persons from a source to a destination. From the above, it can be said that transportation refers to the movement of persons and goods from one location to another. Transport operation also can be viewed as a commercial enterprise which ensures that goods and persons needed at different points in the supply chain of businesses are conveyed in a safe, secure and timely manner.

2.2. Forms of Transportation

- Motor or road, rail, air, water, and pipeline are some of the main forms of transport. Road or Motor transportation which is the movement of goods and services by road is the most frequently used and flexible form of transport among the rest (Stock and Lambert [2]; Tawiah) [7]. Özovaci [14] described road transport as the commonest and the most preferred form of transport because of its ability to ensure that goods and persons are conveyed to places that the other forms of transport cannot reach. Pipeline transport on the other is the movement of good mostly liquid bulk commodities or compressed gases from one point to another by means of connected pipelines (Tawiah) [7]. Özovaci [13] described pipelines as most economic and environmentally safe means of transporting liquid product. This is because the use of pipelines requires gravity to convey the product and also it is mostly constructed at places where human habitation is minimal (Taniguchi and Thompson [6]; Tawiah) [7]. Water transport exists in two main forms namely; maritime transport which is the use of the seas for the movement of goods and persons and inland water transport which is the use of rivers, canals and other inland navigable waters to move goods from place to place (Tawiah) [7]. While most developing nations have not been able to develop their inland waters into navigable waters, the European Union has successfully developed this form of transport and made it one of the most important means of moving persons and goods from different places (Stock and Lambert [2]; Tawiah) [7]. Air transport which has been described as the fastest mode of transport across continents is one of the most important and economic means of moving persons and goods from one continent to another. Even though air transport is employed for the movement of goods, it is more economical for the movement of persons across continent because of its speed. Even though air transport is accepted as one of the major forms of transport, it has received several criticisms especially in terms of its negative impact on the environment (Fair et al. [3]; Tawiah) [7]. Also, rail transportation which is another form of land transport makes use of rails and coaches to convey goods and persons from one location to another. Developments in rail transport especially the use of electrical energy to power modern trains have made rail transport one of the acceptable forms of transport especially in developed nations (Stock and Lambert) [2].Road/ Motor transport is the use of trucks and other road vehicles to convey goods and persons from one point to another by road. This form of transport is the oldest among the rest because of the fact that humans have depended on the use of roads whether fully constructed or not to move goods from one point to another (Humaianes, as cited in Tawiah) [7]. Road transport is described as a means of moving goods and personnel from one place to the other on roads (Economic Times, as cited in Tawiah) [7]. Road is a route between two destinations which has been either paved or worked on to enable transportation by way of motorized means and carriages. Road transport can be classified as transporting or movements of goods, materials or people (Neely [14]; Tawiah) [7]. In the submission of Neely [14], road transport has gained the widest form of acceptance among the other form of transport because of the fact that it enables goods to be delivered from door to door. Roads most often extend to remote locations where other forms of transport do not extend to. This door to door reach of road transport ensures that businesses are able to reduce cartage, loading and unloading and their associated costs. Another advantage of road transport is that it requires less capital relative to the other forms of transport. Ships, trains and planes are all expensive compared to trucks (Tawiah) [7]. Aside the relatively less capital cost for trucks, the cost of maintenance and operations of these trucks is also lesser than those of ships, trains and planes. It also has a lesser risk of damaging goods in transport and most suitable cheapest mode of transport for short distance in the delivery of goods and services (Collis and Hussey) [15]. In spite of its broad acceptance, road transport has not been without criticisms that the other forms of transport have been subjected to (Economic Times, as cited in Tawiah) [7]. Road accidents have been identified as one of the most dangerous risks associated with road transport especially for the movement of persons and goods. Again, unlike the other forms of transport, trucks and other vehicles which are used for transportation of goods by roads can only transport a limited quantity of goods (Collis and Hussey [15]; Tawiah) [7].

2.3. Role of Transportation in the Supply Chain

- The role of transportation in the supply chain of business cannot be overstressed. As the supply chain of businesses develop from a localized concept to a global one, transportation becomes critical in improving the performance of businesses. Gupta et al. [16] noted that factors such as increase in technology, and the global demand for resources and increase trading activities between countries led to a significant increase in the level of demand for transportation. Supply chain efficiency is synonymous with transportation efficiency (Möller and Törrönen) [17]. This implies that in order for organizations to ensure an improvement in the level of performance of their supply chain there is the need for them to pay attention to the level of efficiency of their supply chain. Gupta et al. [16] further described supply chain as an amalgamation of transportation, logistics and distribution management activities in organizations. This shows that transport management is a major fulcrum which supports the success of supply chain management in organizations. On their part, Coyle et al. [18] opined that the overall efficiency of the supply chain of business is based in the level of effectiveness of transport activities. This is because transportation is the main activity which connects an enterprise with its suppliers and with its customers through the flow of materials. A combination of the various forms of transport results in such innovations as intermodal and multimodal transport systems. Intermodal transportation involves the use of two or more modes of transports to transport goods from the source to the destination. In this approach of transportation all entities involved in the transportation process bear responsibility for their leg of the journey under the control. The transporter who is responsible for that stage of the journey bears cost of that damage. Multimodal transport on the other hand consists of the use of different forms of transport for the movement of goods from source to destination with the just one transporter (the multimodal transporter) bearing responsibility for the entire journey of the cargo (Möller and Törrönen [17]; Tawiah) [7].

2.4. Key Factors in Selecting a Transport Mode

- A number of factors affect the choice of transportation mode in different organizations. Some of the factors affecting the choice of a mode of transport in organizations include: speed, accessibility, safety, reliability, capacity, fuel efficiency, privacy and comfort (Vaddadi) [19]. Accessibility is another factor which businesses need to consider when making a decision on the mode of transport to use (Coyle et al. [18]; Tawiah) [7]. Aside accessibility, Coyle et al. [18] itemized transport cost and quantity of cargo to transport as the other factors which are considered when choosing a mode of transport. The choice of a given mode of transport depends on factors such as cost-benefit analysis and also the capacity to convey the quantity of goods needed to be conveyed (Tawiah) [7]. More so, Möller and Törrönen [17] identified speed and cargo security as vital in any decisions on the mode of transport to convey goods. Businesses keep their customers satisfied when goods are delivered on time and since the delivery of goods is dependent on the transport the need for speed is considered as a vital factor when selecting a transport mode. Aside speed, businesses also need to ensure that cargo transported reach the destination or customer in an acceptable condition. When cargos reach their destination in a damaged or deformed condition, it leads to various forms of losses such as loss of customers and financials loss. Cargo damages also lead to various forms of disputes and their associated consequences, hence the need to ensure that cargo is securely transported (Möller and Törrönen [17]; Tawiah) [7].Another factor considered by organizations in this era of environmental sustainability is carbon emission. Transport management decisions in business organizations especially in the developed nations now takes into consideration the mode of transport which has the least damaging effect on the environment. Green businesses as they are to ensure that as much as possible, they avoid the use of any mode of transport which pollutes the environment (Coyle et al.) [18]. Vaddadi [19] noted that factors such as comfort, safety and privacy are the ones which are most often considered. Passengers travelling over long distances need to do so in comfort. They want to reach their destination without undue aches and pains (Tawiah) [7].

2.5. Factors Affecting Transport Management Practices

- The choice of a carrier mode and how to effectively manage it is one of the most important transport management practices in organizations. Factors such as delivery time and form of transportation are considered when planning the choice of carrier to employ for the conveyance of goods from a point of origin to the point of destination (Meixell and Norbis [20]; Tawiah) [7]. Also, performance variables such as selecting mode of transport and carrier, negotiating rates and service levels, and evaluating carrier performance (Monczka, Trent and Handfield) [21]. Based on these variables, businesses are able to decide which carrier or transport operator is more efficient and which one is not (Tawiah) [7]. In the views of Jahre and Hatteland [24], one of the most important factors to consider in transport management is the need to ensure that the cargo arrives safely and also make the most of the cargo spaces which have been booked. Safe cargo delivery depends on such factors as secure stowage of cargo. This calls for the usage of the appropriate stowage equipment and effective planning cargo stowage (Tawiah) [7]. Businesses decision making regarding load optimization involves making decision regarding less than container load (LCL) into full container loads (FCL). Where business will have to make decisions on whether to consolidate the cargo and use LCL or make use of the entire cargo space as FCL (Jahre and Hatteland) [22]. Another factor which is considered as part of the load planning and optimization is the use of appropriate packaging. There is the need to ensure that the cargo been transported is properly packaged to improve its safety during its transport (Prendergast) [23]. Transport management requires specific instructions delivered to the transport operator. The need to ensure that goods arrive at a specific destination leads to businesses to issue specific set of instructions to the transporter. These instructions form the basis of the activities of the shipping service provider (Tawiah [7]; Tseng et al.) [4]. Besides, businesses which have placed their goods on any vehicle desire to be able to know the location and condition of the cargo at any given point time. Cargo tracking has therefore become a critical aspect of shipment planning and execution in organizations which often move their goods from place to place (Younkin, as cited in Tawiah [7].Shipping service providers are expected to provide notification to shippers regarding issues such as bill of laden, mates receipt and other similar documents. There is the need for businesses and shipping service providers exchange information on the status of the cargo at different times of the journey (Tawiah) [7]. When cargoes are transshipped, stored in a temporary location or even transited through over locations, there is the need for shipping lines to be able to inform the cargo owner appropriately. Such notifications are done in the form of emails and other forms of electronic messaging (Grant et al.) [26]. Proactive notifications are provided by leading carriers routinely whenever shipment delivery or pickup is in jeopardy for any reasons for instances stoppage by customs for inspection (Kova´cs and Spens [24]; Tawiah) [7]. Transport services are provided at a cost which is also referred to as freight. Payment of freight in shipping is affected by such factor as the place of payment; the payee and the currency of payment. These factors and more make the payment for transport services on the international stage a very complex task. There is a growing recognition of the fact that the existence of large shipper’s scale and technological advances now drives efficiencies in freight payment processes (Chopra and Meindle [11]; Tawiah) [7]. Effective cost management also helps to support the ability to generate revenue from transportation operations (Naim, Potter, Mason and Bateman [25]; Tawiah) [7].Regarding transport infrastructure, Davids [26] contends that poorly constructed and poorly maintained roads a common in most developed nations. This situation hinders the ability of the transport sector to develop to its full potential. Aside the poor state of infrastructural development, there are weak institutional mechanisms for regulating the transport sector especially in most developing nations which has impeded the performance of the transport sector. Although several policies and conventions have been developed in developing nations to ensure efficiency in the transport sector, there is a general lack of effective implementation leading to poor results of such policies and conventions (Davids [26]; Tawiah) [7]. In an effort to deepen the debate, Lewis, as cited by Tawiah [7] opines that the general poor maintenance culture in most developing nations finds manifestation also in the transport sector. Transport vehicles in most developing nations are poorly maintained leading to frequent breakdown and accidents. Poor transport vehicles in developing nations have been blamed for the lack of cargo insecurity associated with transport management in those nations. The high level on uncertainty associated with transport management in developing nations has resulted in the sector trailing its counters in the developed nations by a significant margin (Tawiah [7]; Weisbrod, Vary and Treyz) [27]. Lewis [28] argued that unstable economic conditions in most developing nations have led to the businesses requiring high level of capital which is also difficult to obtain before they can successfully take off. The capital requirement for setting up of transport businesses in most developing nations is so high that only a few businesses and individuals are able to establish such businesses. This has led to a low level of competition and ultimately pervasive inefficiencies in the delivery of transport services (Tawiah) [7]. The cost of experts in terms of maintenance culture to within the transport sector has also become a major concern. The high cost of maintenance has led to the usage of poorly maintained vehicles which are prone to frequent breakdowns and cargo damage. The lack of adequate number of transport experts coupled with the high labor cost for these persons have also affected transport management in developing nations such as Ghana (Tawiah [7]; Weisbrod et al.) [27]. On their part, Rodrigue, Comtois and Slack [29] argue that urbanization has created a high demand for transport services around the world. The implication is that as urbanization increases, the demand for transport services will also increase therefore the capacity of the transport sector must always be increase to meet the level of demand from the urbanization, its limitation will adversely affect urbanization and its associated economic development (Fawcett [30]; Tawiah) [7]. Underinvestment in transport infrastructure could have dire consequences on passengers’ mobility, logistic system and the entire social and economic activities (Eddington) [31]. Furthermore, Rodingue et al. [29] noted that transport management within developing nations is characterized by poor infrastructure, weak institutional mechanism for regulating the sector, poor maintenance, high initial capital requirement, lack of transport management expert and poorly trained operators. Harriet et al. [32] stated that product availability and price in a given market are often influenced by the existing state of transport operations in those organizations. Poorly managed transport operation with its associated challenges leads to such problems of short supply of precuts on the market and increased product prices. Therefore, efficient and effective transportation management is key for ensuring socio-economic development (Harriet et al.) [32].

3. Methodology

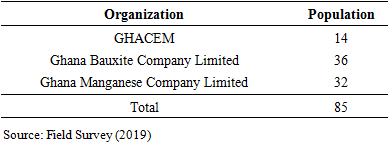

- Research approaches are broadly classified into quantitative, qualitative methods and the mixed methods approaches. The study made use of the mixed methods to examine and make presentations on the subject matter which is challenges associated with transport management in organizations. Creswell, as cited in Tawiah [7], noted that the advantage of employing mixed research approach by researchers is to ensure that the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches are harnessed in a study. The rationale behind the study’s choice of mixed research approach is to ensure diversity in the views based on the perspectives of different research participants. The study also employed descriptive survey design to solicit the views of respondents on the subject of transport management and the factors which are affecting it in their respective organizations. Saunders et al. [33] described a descriptive survey design as a research plan which enables researchers to make a presentation of the findings of a study based on the actual experience of the respondents. In descriptive studies, the research does not make an attempt to interpret the responses obtained by presents them exactly as the respondents provided. McMillan, as cited in Odoom, Opoku and Ntiakoh-Ayipah [34], states that descriptive design captures a report of the way things are, what is or what has been or has happened. Babbie, as cited in Odoom, Opoku and Ntiakoh-Ayipah [35], and Shuttleworth, as cited in Odoom, Fosu, Ankomah and Amofa [36], maintain that descriptive survey design has the advantage of helping the researchers obtain unbiased views about the issues under investigation. The study sought to examine the challenges of transport management in business organizations in Ghana. However, it focused on Ghacem, Ghana Bauxite Company Limited and Ghana Manganese Company Limited. Specifically, the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis Branches of these companies were the focus of investigation. The population therefore consisted of the employees and managers of these three organizations who are responsible for logistics and transport management. The entire population in each of the three organizations was considered as part of the study’s sample size by census. The employees of these three organizations all work within the same location. In addition, their population sizes are small enough for them to be covered within the time frame for completion and submission of the study. Table 1 presents the breakdown of the employees from the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis Branches of the three companies, apart from the managers. The total population was therefore 85 including the managers.

|

4. Results and Discussion

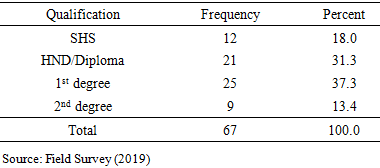

- The results and discussion section is presented in two ways. The first part is devoted to the demographic data of results whilst the second part looks at the key issues which informed this study. To start with, the responses on the sex distribution of respondents indicated that the majority (81%) of the employees who work in the transport management sections of the selected companies and were males while a relatively small proportion (19%) were females. Table 2 presents the results on educational level of respondents. The study showed that 18.0 percent of the respondents had obtained Senior High School as their educational qualification whilst 31.3 percent had obtained HND/diploma as their qualification. On the whole, it can be seen that majority (68.6%) of the respondents from the study organizations had between HND/Diploma and 1st degree as their educational qualification. With respect to the educational background of the respondents, the responses obtained indicated that (49%) had first degree them while 30% had diploma in various fields of study with the remaining 21% also indicating that they had completed their master’s degree.

|

4.1. Number of Working Years

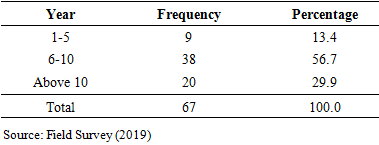

- With respect to the number of working years, the responses obtained indicated that the majority (57%) of the participants had worked in their respective organizations for a period of 6-10 years while those who had been with their companies for over 10 years constituted 30%. The remaining 13% of the respondents had been with the company for a period of 1-5 years. This information is also presented in Table 3.

|

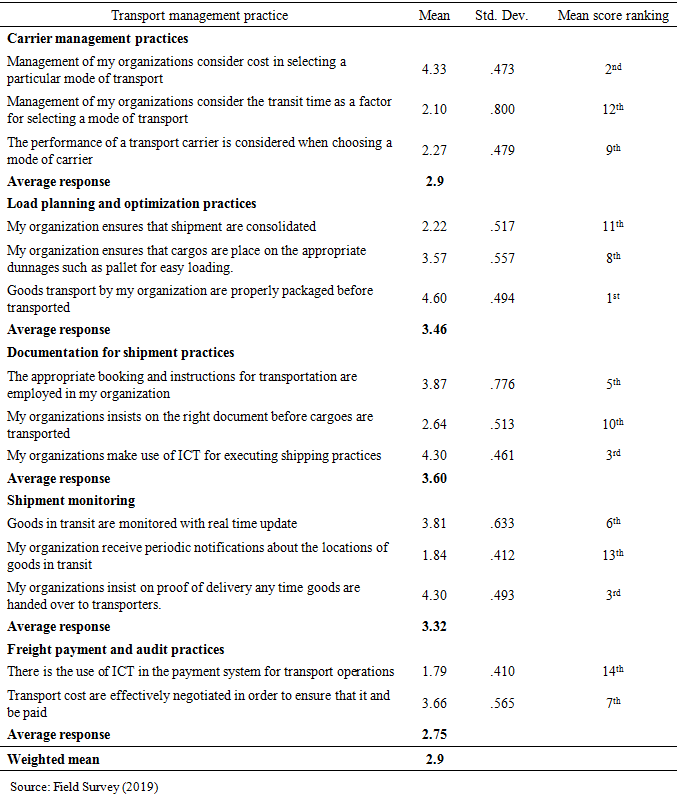

4.2. Transport Management Practices in STM

- The first part of the study was to examine the transport management practices employed by businesses in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis. Means were calculated on a scale of 1 to 5; 1 representing very lowly agree, 2 representing lowly agree, 3 representing moderately agree, 4 representing strongly agree, and 5 representing very strongly agree. The results obtained in this regard are presented in Table 4. With respect to carrier management practices, the mean score of 4.33 shows that the respondents strongly agreed that cost is one of the most important factors considered before selecting a carrier. However, with a mean score of 2.10 the respondents lowly agreed that businesses pay attention to transit time for cargo and consider the performance of a carrier when making a choice for a carrier. The average response of 2.9 suggests that respondents moderately believed that in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis, businesses pay little attention to issues relating to carrier management. The results of this study depart from the findings of Meixell and Norbis [20] and Monczka, Trent and Handfield [21]. The authors observed in their studies that carrier management is one of the factors businesses considered to ensure an effective transport management.

|

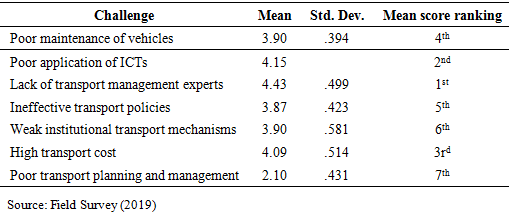

4.3. Challenges Associated with Transport Management in the Metropolis

- The second objective of the study sought to explore the challenges associated with transport management in business organizations in the metropolis (Table 5).

|

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The study sought to examine the transport management practices employed by companies in the STM. Based on the findings, it is concluded that the main transport management practices are: carrier management, load planning, documentation, monitoring and payments. However, more attention is paid to load optimization, documentation issues and monitoring of cargo in transit with less attention on carrier management issue and payment related issues. The greatest challenge confronting transport management in the Metropolis is the general lack of transport management experts, followed by high cost of transport operations, poor vehicle maintenance and ineffective transport policies in organizations. Other challenges include weak institutional mechanisms and poorly planned transport operations. Besides, cost of transport and poor road networks are crucial factors hindering transport management within the Metropolis. Again, there is a very low application of ICT in transport management in STM. It is therefore recommended that companies in STM should endeavor to give their personnel managing their transport operations sufficient training in order to improve their level of performance and ultimately the performance of the entire organization. Therefore, it is recommended that companies in the Metropolis should design clear strategies to effectively manage their transport costs. Also, the government is called upon to fashion out innovative ways of addressing deficits in road networks especially in the rural part of the Metropolis. Finally, the study recommends that Management of companies within the Metropolis should train their employees on the use of ICTs and also procure suitable software for the management of their transport operations.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML