-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2020; 10(2): 82-96

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20201002.04

Bank Performance, CEO Ethics, and Compensation: Evidence from Nigeria

William Mbanyele

Center for Economic Research, Shandong University, Jinan, China

Correspondence to: William Mbanyele, Center for Economic Research, Shandong University, Jinan, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study analyses the impact of bank performance, and CEO ethics on compensation for large listed banks in Nigeria from 2006-2016. The study employs alternative measures of bank performance and a self-constructed CEO ethics index to analyze the determinants of CEO pay. The study shows that bank performance does not influence CEO cash compensation while the CEO’s ethics negatively influence CEO compensation. The study reconciles the mixed evidence in agency literature on tenure and pay association by showing that increased tenure for ethical CEOs adversely affects CEO pay. On the contrary, increased tenure for unethical CEOs positively affects compensation, which suggests that prolonged tenure for unethical CEOs contributes to entrenchment and excessive compensation. The study findings show that manager ownership concentration, leverage, and board size are negatively related to CEO compensation. Overall the study recommends performance-based compensation, tenure limits, and ethical awareness to strengthen corporate governance in the banking industry.

Keywords: CEO compensation, Nigerian Banks, Bank performance, CEO ethics, Corporate governance

Cite this paper: William Mbanyele, Bank Performance, CEO Ethics, and Compensation: Evidence from Nigeria, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2020, pp. 82-96. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201002.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- CEO compensation literature has immensely increased in recent years, especially from the developed world. Regulators, shareholders, and scholars raised concerns about the so-called excessive and unethical CEO compensation trends, and this prompted interests among the researchers, particularly after the global financial crisis, to investigate factors that determine CEO compensation. The optimal contracting theory explains the rising compensation trends as feedback effects of incentives given to managers by boards and remuneration committees in a bid to motivate CEOs to increase firm performance and to retain talent in the firm (Gabaix & Landier, 2008). On the contrary, the managerial power proponents attribute the changes in pay trends as indications of rent extraction due to excessive power by CEOs who directly or indirectly determine their pay in firms with weak governance structures (Bebchuk & Fried, 2003). The neck on neck arguments in literature on the determinants of CEO compensation are mainly discussed in the context of western countries. However, there is less attention given to the study of bank CEO pay determinants in emerging markets, especially in Africa. Therefore understanding how CEO pay is determined in developing nations remains an important area of discussion; hence this paper empirically investigates how bank performance and CEO ethics affect CEO cash compensation in Nigeria. Besides, most CEO compensation studies focus on non-financial companies, and their findings may differ from those of banks as they operate in a different regulated environment (Houston & James, 1995). In addition, this study gives a narrative on the factors that determine bank CEO cash remuneration from the perspective of an emerging economy in Africa. This study seeks to contribute and extend the existing literature by empirically analyzing how firm performance and CEO ethics influence CEO compensation in banks. There is a heated debate in corporate finance and management scholarship on the determinants of CEO pay. Literature defines CEO pay as a function of tenure (Zheng, 2010), corporate governance (Bebchuk & Fried, 2003), firm value (Lee & Chen 2011), executive ownership (Chung & Pruitt, 1996) and firm size (Zhou, 2000). However, little attention has been given by corporate finance and management scholars to empirically examine how ethics as a managerial characteristic affects the level of CEO pay. Few studies focus on how ethical leadership affects performance (Eisenbeiss, Knippenberg, & Farbrach, 2015), corporate reputation (Olorunfemi, Chinonye, Ayodele, Uchechukwu, & Fatai, 2018b), and workers' business deviance (Neves & Story, 2013). This study fills this gap in corporate finance literature by examining the effect of personal CEO ethics on compensation using a self-constructed principal component analysis measure of ethics. Studying CEO ethics is very important in complex and sensitive institutions like banks as unethical behaviors are at the core of the most dreadful events the modern financial world has ever known; for example, the Enron crisis. An ethical CEO who espouses unselfish desires (Feng, Zhang, Liu, Zhang & Han, 2018) is likely to work in the interests of the business stakeholders and may not use managerial power to capture boards in a bid to expropriate large sums of pay. Ethical CEOs have moral obligations to decline excessive payment, which prejudice shareholders (Moriarty, 2009). However, an unethical CEO is likely to influence the board to pay more compensation, even if the business is not performing very well (Harris & Bromiley, 2007). The study focuses on Nigeria, among other countries for several reasons. Firstly since Nigeria is the largest economy in Africa and has the second-largest banking sector in Africa, the study results inform literature and policy on the main determinants of CEO pay in Africa and other developing countries with similar institutional environments. Secondly, this study extends the agency literature on compensation from a different institutional background with weak institutions. Most studies on CEO pay focus on western countries like the USA (Murphy, 1998; Core, Guay, & Larcker., 2003), Canada (Zhou, 2000), UK (Buck, Bruce, Main, & Udueni, 2003), Netherlands (Duffhues & Kabir, 2008) with little focus on emerging countries South Africa (Deysel & Kruger., 2015) and Nigeria (Olaniyi, & Obembe, 2017). There is scanty literature on the causal factors of bank CEO compensation in Sub Saharan Africa. The African institutional environment is characterized by low regulatory monitoring of banks as compared to the developed nations. There is some evidence that managers exert much power on firm decisions in institutional environments with weak corporate governance. A nation's institutional, legal, economic, or social environment has a significant impact on the level of CEO remuneration. Hence the study findings on Nigeria are likely to differ from other results from the US and Europe, which makes this study unique as it complements compensation literature from a country with weak institutions. The Nigerian banking industry is still in the reformatory stages. It is yet to meet a high standard status of a stable and well-governed industry as the country is gradually aligning its corporate governance system with the OECD principles of good corporate governance. As a gesture of commitment towards useful corporate governance framework in Nigeria, regulators have since compelled banks among other firms to be transparent by publishing the CEO compensation metrics and adopting pay for performance mechanisms. These recent developments make this study relatively comparable with other studies in countries that have robust corporate governance systems. Lastly, the study findings are not only essential for Nigeria but also for other emerging nations that are in the process of enforcing functional corporate governance mechanisms to prevent expropriation of shareholders’ wealth due to excessive and unjustifiable CEO pay. This study is similar in scope with Omoregie, & Kelikume (2017) study on how bank performance affects CEO pay in Nigeria. However, this study is different from their research in different ways. Firstly this study uses more alternative measures of firm performance, which include accounting metrics like return on assets and return on equity and market measures like Tobin Q and stock return rather than using the return on equity only as in Omoregie, & Kelikume (2017). Using alternative measures of bank performance helps to evaluate the influence of firm value on CEO pay thoroughly. Another closely related research by Olaniyi & Obembe (2017) attempted to explain the determinants of CEO pay in Nigeria. This study differs from Olaniyi & Obembe (2017) as it unbundles the impact of a CEO's ethics on cash compensation. Nigeria is one of the countries with high corruption and low stakeholder protection, which is a conducive environment for rent extraction by unethical managers. Hence the need to study the impact of CEO ethics on pay in the Nigerian banking sector. This study is critical as it analyses the extent to which a bank corporate governance system can curb individual unethical behavior influences on cash compensation. The study also uses a more extensive sample period than Olaniyi & Obembe (2017), which increases the predictive power of the results. Other studies on the Nigerian banking industry focus on how CEO pay affect bank performance (Kurawa & Saidi, 2014; Olalekan & Bodunde, 2015) while this study analyses the impact of bank performance and CEO ethics on CEO pay. The study contributes to managerial compensation literature in several ways, firstly by showing that bank performance does not influence the CEO pay. Secondly, the study shows that the CEO’s ethics negatively influence CEO compensation. Thirdly the study report that a long tenure for ethical managers is negatively related to CEO pay while a long term tenure for unethical managers positively influences CEO compensation. Besides, the study findings show that manager ownership concentration, leverage, and board size are negatively related to CEO compensation. Lastly, the study shows that gender diversity positively affects CEO pay.The remainder of our study is as follows; Section 2 covers literature review and hypothesis development; Section 3 contains the research data and methodology of the study, section 4 explains the study findings and discussion. Section 5 contains the conclusion and policy implications.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Firm Performance and CEO Compensation

- According to literature in the spirit of the agency theory, the CEO should be given pay as a reward for performance to align the managers’ interests with shareholder objectives (Jensen & Murphy, 1990; Jensen & Meckling, 1976). However, literature is ambiguous on whether compensation incentives for executives are beneficial for the shareholders. Some studies support the efficient contracting hypothesis, which eludes that CEO compensation deals with the agency problem by motivating managers to put more effort, which increases firm performance (Abernethy, Dekker, & Schulz, 2015). On the contrary, entrenched managers enrich themselves with large amounts of pay, which value destroy the wealth of shareholders (Bebchuk, Cohen, & Ferrell, 2009). According to the managerial power proponents, the CEO influences the remuneration committee to solicit high levels of compensation, especially when there are weak corporate governance mechanisms (Bebchuk & Fried, 2003). Thus according to the entrenchment hypothesis, CEO pay is not a function of firm performance; instead, CEO pay is a function of managerial power. Jensen & Murphy (1990) study on US firms shows an insignificant positive impact of firm performance on CEO compensation. Also, Yang, Singh, & Wang (2019) studied a sample of 225 Canadian firms and showed that firm performance has little impact on CEO pay. Furthermore, Zhou (2000) shows a weak association between compensation and performance. Switching to the banks' literature, Mayers & Smith (1992) show that there is less pay for performance sensitivity in regulated industries like banks than in other industries with low regulation. Mayers & Smith (1992) analysis resonates with a study on Nigerian banks by Omoregie & Kelikume (2017), which show that there is no significant association between return on equity (ROE) and CEO compensation. Conyon & Murphy (2000), in their study of US and UK firms, observed that share returns influence non-cash CEO compensation as compared to cash compensation. Also, some shreds of evidence show that firm performance mainly influences CEO equity pay as compared to cash pay (Jensen & Murphy, 1990). However, another strand of literature views pay as a managerial reward for putting effort, and thus from the optimal contracting theory, firm performance positively influences CEO pay (Buachoom, 2017; Cambini, Rondi, & Masi., 2015; Olaniyi et al., 2017). Smirnova & Zavertiaeva (2017) studied a sample of 330 European companies and concluded that firm performance significantly affects CEO compensation. In another study, Vemala., Nguyen., Nguyen., & Kommasani, (2014) give evidence of a significant positive effect of firm performance on CEO pay in a study of 249 Fortune 500 firms, before and after the 2008-2009 financial crises. Ozkan (2011) studied 390 UK firms from 1999-2005 and found a significant positive impact of firm performance on CEO cash remuneration. Furthermore, Conyon (2014) study results on UK companies exhibit a significant positive association between firm value and CEO compensation. Building on the same literature, Farooque, Buachoom, & Hoang, (2019) studied 432 listed Thai companies and established a positive relationship between performance and pay. Consistent with studies on non-financial firms, Huang & Chen (2010), in their study on a sample of 48 banks in the US, established a positive association between pay and performance. Also, Tafamel & Machame (2014) study using Nigerian banks show that bank profitability impacts CEO compensation positively. Thus the evidence from the agency optimal contracting literature posits that banks reward their executives with more bonuses and other monetary benefits in times of plenty to motivate managers to work very hard. Considering the inconclusive evidence in the literature, the study frames the following hypotheses:Hypothesis 1a: There is no relationship between bank performance and CEO compensation.Hypothesis 1b: There is a positive relationship between bank performance and CEO compensation.

2.2. CEO Ethics and Compensation

- The CEO's ethics, directly or indirectly, influence the compensation levels of the CEO. Firstly in some jurisdictions with weak governance systems, the CEOs are part of the compensation committees or supervisory committees that determine CEO pay. Hence there is a high likelihood that corrupt and unethical CEOs may use their power to manipulate the directors to allocate themselves excessive cash compensation (Bebchuk & Fried, 2003). Secondly, the other channel that CEO may use to expropriate rent is through co-opted boards. CEOs are responsible for choosing some directors who may end up in the compensation or supervisory committees, which design pay contracts for the CEO (Bebchuk & Fried, 2006). Therefore the CEO sits in the compensation committee as a dummy represented by some director friends or co-opted directors. Thus the CEO's unethical behavior can weaken the power of the board to perform its monitoring oversight role (Zhu & Chen, 2015). Unethical CEOs use various means to defraud companies through earnings management, share price manipulations here, and financial misstatements (Harrison, Summers, & Mennecke, 2016). Dishonest and corrupt CEOs tend to influence weak board structures to secure excess compensation (Harris & Bromiley, 2007). In contrast, selfless and honest ethical CEOs are driven by inert moral principles to act in the interests of their principals and decline above average compensation (Moriarty, 2009). Therefore, the study expects a negative relationship between CEO ethics and compensation as ethical CEOs accept modest fair salaries and decline excessive pay packages. Thus the following hypothesis is framed:Hypothesis 3: There is a negative relationship between CEO ethics and cash compensation.

2.3. CEO Ethics, Tenure, and Compensation

- CEOs usually inflate earnings to gain market reputation and increased wealth through pay for performance rewards based on manipulated performance metrics. Ali & Zhang (2015), in their study, established a close connection of CEO tenure with earnings management practices in businesses with weak corporate governance mechanisms. Thus the more years CEOs spend in the business, the more influence they exert in shaping companies' policies, which may also include compensation policies. The study conjectures that an increase in tenure for ethical CEOs is negatively related to executive compensation, thus leading to the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 4: The interaction effect of CEO ethics and tenure is negatively related to cash compensation.

3. Research Data and Methodology

3.1. Data and Variables

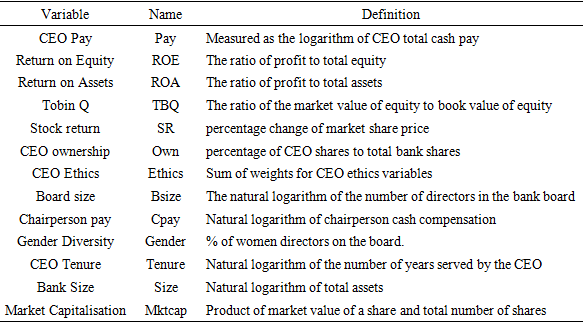

- The study focused on a sample of large listed banks in Nigeria from 2006-2016 with a cumulative total market share of more than 70% in the banking sector, which dispels the worry over results reliability as the sample represents the major players in the banking industry in Nigeria. This period covers a period of corporate governance reform in Nigeria marked by two prominent corporate governance codes pronouncements in the Nigerian banking industry, which makes the period a natural experiment to study how CEO pay is determined. The year 2006 is when the study sample begins, and it marks the year when the code for corporate governance for banks comes into effect in response to poor governance leading to consolidation of several banks, thereby significantly reducing the number of banks in Nigeria. In 2014 the banks and discount houses corporate governance code was further refined to strengthen high standards of corporate governance in the Nigerian Bank industry. The change in the governance code helps us to study the causal effects of corporate governance on CEO compensation in Nigeria following this exogenous shock. I drop all banks with no consistent data for the whole sample period. I obtained data for firm values and governance measures from (Olorunfemi, Chinonye, Oluwole, Odunayo, & Ezekiel; 2018a) dataset. The study merged the data with the ethical leadership dataset, which is used to calculate CEO ethics scores collected from a survey of around 500 bank employees of top banks in Nigeria (Olorunfemi et al., 2018b). After that, I merge the data with the bank board size data set (Eluyela, Akintimehin, Okere, Ozordi, Osuma, Ilogho, & Oladipo, 2018), and after dropping all banks with insufficient information, the overall data contain 88 firm-year observations. Dependent VariableThe study calculates the dependent variable CEO pay using cash compensation, as this is the primary method used to pay executives in developing countries with growing stock markets. Data on non-cash compensation is not readily available due to disclosure challenges faced by most countries, especially in Africa (Olaniyi et al., 2017). A couple of studies use cash compensation as a measure for CEO pay (see Zhou, 2000; Benito & Conyon, 1999). To reduce the skewness of the data, the study uses the natural logarithm of CEO cash compensation as the independent variable. Main explanatory variablesFirm performanceFollowing literature (Jensen & Murphy, 1990; Singh & Agarwal, 2002; Sun, Wei, & Huang., (2013), two accounting firm performance measures are used to analyze their impact on CEO compensation which are return on assets (ROA) and return on equity(ROE). The paper also makes uses of market performance measures, stock return (SR), and Tobin's Q (TBQ). I analyze the stock return impact on CEO compensation in harmony with other incentive studies (Su, Baird, & Schoch, 2015). Several studies found out that the firm stock returns have a significant positive impact on CEO performance (Dee, Lulsegeda, & Nowlin, 2005; Banker, Darrough, & Plehn-Dujowich., 2013). CEO EthicsPersonal personalities are complex and challenging to measure, and the study tried to measure the CEO ethics following prior studies. The study builds the ethics measure from the definition of ethics provided in the literature, according to Chughtai (2016), ethics consist of good attributes exhibited by an individual in the absence of public monitoring. An ethical individual has high moral values that influence his behavior (Lu & Guy, 2014). The study measures CEO ethics following other ethical leadership literature as the index of empathy, fairness, value for long term success, trust, and tone. We calculate the index using five Likert items from the survey of around 500 bank employees using the multi-sampling technique(see Olorunfemi et al., 2018, for the survey description). After constructing a Likert scale ranging from 1 to five, the study employs validity tests to ascertain whether all variables are measuring CEO ethics. A validity test shows the Cronbach's alpha value of 0.926, which confirms that the five variables are all measuring the same thing. All the factor loadings for the five variables are above 0.68, and the indicator reliability measures are above 0.47 for all variables at 1% significance level. After conducting validity tests, the scores are treated as continuous variables and averaged to get a mean score per variable per bank. After that, all variables are assigned equal weights and summed to calculate the total CEO ethics score for each bank. ControlsThe study controls for corporate governance variables that influence CEO pay, CEO ownership, tenure, board size, and gender diversity. According to Core & Guay (1999), manager ownership is one of the main determinants of CEO compensation. However, Banghøj et al. (2010), in their study of Denmark firms, showed an insignificant positive association between CEO ownership and pay. CEO ownership is the CEO shareholding expressed as a percentage of the total bank shareholding. Long term CEO tenure may build conducive environments for CEO board coalition and excessive power to manipulate firm compensation policies. CEOs who serve more years may benefit from co-opted boards, which may give them return favors in the form of large sums of pay. Several studies use CEO tenure as a proxy variable for CEO entrenchment. Chung & Pruitt (1996) and Clarkson, Van Bueren, & Walker, 2006) posit that CEO tenure positively affects compensation. However, Ascherl, Schrand, Schaefers, & Dermisi., (2019) found no link between tenure and CEO pay. Furthermore, Banghøja, Gabrielsen, Petersen, & Plenborg, (2010) in their studied private companies and found no significant connection between CEO tenure and compensation. I measure tenure as the logarithm of the number of years the CEO has been serving in the bank. The board of directors is a pillar of corporate governance and is responsible for monitoring and contracting managers (Jensen, 1983). Corporate boards are responsible for setting and approving the CEO pay via the compensation or supervisory committees. The board size is associated with increased monitoring, which increases firm value (Ntim, Opong, & Danbolt., 2012). Some studies suggest that board size positively determines the level of CEO compensation (Core et al., 2003; Ozkan, 2011). The study measures board size as the natural logarithm of the total of members who sit on the board. Women directors are very pivotal in strengthening corporate governance due to peculiar feminine traits that change the status quo in board performance (Adam & Ferreira, 2009). Some studies posit that gender diversity positively impacts CEO compensation (Benkraiem, Lakhal, & Toumi, 2017). I measure gender diversity as the percentage of females who serve on the board. I expect a positive influence of women directors on CEO pay. In addition, the study controls for bank size and leverage following literature. Large businesses have many responsibilities and need excellent skills to manage them, which leads to high compensation for CEOs effectively; this argument is rooted in the human capital theory (Murphy, 1999). The CEO compensation increases as the firm size increase as most large companies will be competing for excellent personnel on the labor market. Large businesses pay high levels of compensation to keep the CEOs in the firm; otherwise, they will go to other well-paying firms. Some studies show that firm size is one of the most critical determinants of CEO compensation (Tosi, Werner, Katz, & Gómez‐Mejia, 2000). Nulla (2013) and Zhou (2000), in their studies on Canadian companies, give evidence of a positive impact of firm size on CEO pay. Also, using a sample of US companies by Ascherl et al. (2019) show that firm size positively impacts CEO compensation. The study controls for leverage; the argument is that if a business is highly leveraged, the manager will be under heavy monitoring, which may limit the CEO from getting hefty compensation. If the leverage levels are low, the CEOs will likely use their powers to expropriate rent from shareholders through excessive compensation. Following Huang and Chen (2010), the study measures leverage as the ratio of total assets to book value of equity.

3.2. Methodology

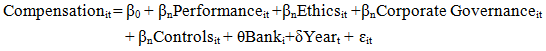

- The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimation method is used with robust clustered standard errors to deal with heteroskedasticity. The study alternatively uses the fixed effects estimation method as it is a perfect fit for the data considering that the main variables vary within individuals and time. The basic regression estimation model is as follows:

| (1) |

|

3.3. Summary Statistics

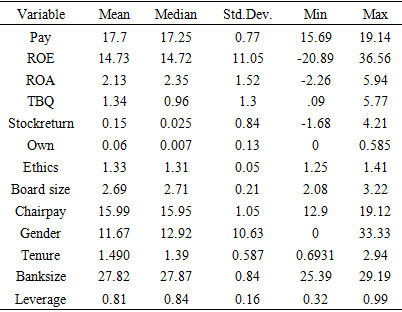

- Table 2 shows the summary statistics for the variables under investigation for a sample of Nigerian banks. The results for the median and mean are very close to each other except for CEO ownership (own); this means that the results do not suffer from any bias found in skewed data. Summary statistics in Table 2 show that the cash compensation for bank CEOs in Nigeria does not widely differ, as shown by the thin disparity between the minimum and maximum compensation levels. In addition, the bank sizes are also almost the same, and this may be because of the amalgamation of banks in Nigeria in 2006. Table 2 results show that banks in Nigeria have high leverage ratios, just like banks in other jurisdictions; banks usually have more liabilities, which are usually dominated by customers' bank deposits. The summary statistics in Table 1 show that some banks do not have gender representations in the boards, as demonstrated by a minimum of zero value in some banks. Another notable difference in bank characteristics is the tenure of the CEOs. The summary statistics seem to suggest that some banks offer long tenures while some offer short term contracts to managers. Most CEOs in the Nigerian banking industry have long tenures, which usually contribute to entrenchment and excessive power. Powerful CEOs may capture boards and extract rents from shareholders. The summary statistics for return on equity show a large standard deviation of 11.05 and a standard deviation of 1.52 for return on assets, which highlights that there are some distressed banks with low capital levels as measured by the bank’s equity.

|

4. Empirical Findings and Discussion

4.1. Bank Performance and CEO Compensation

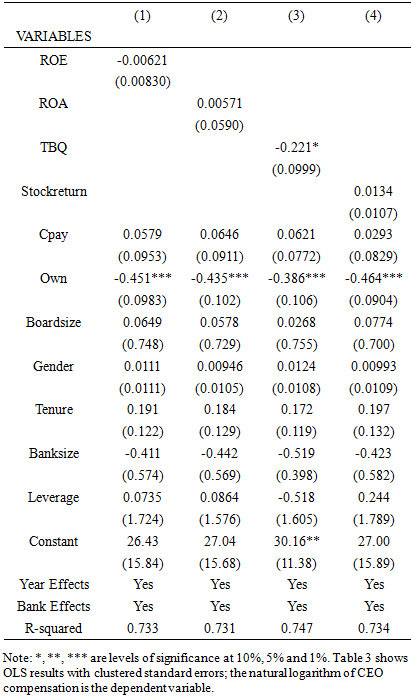

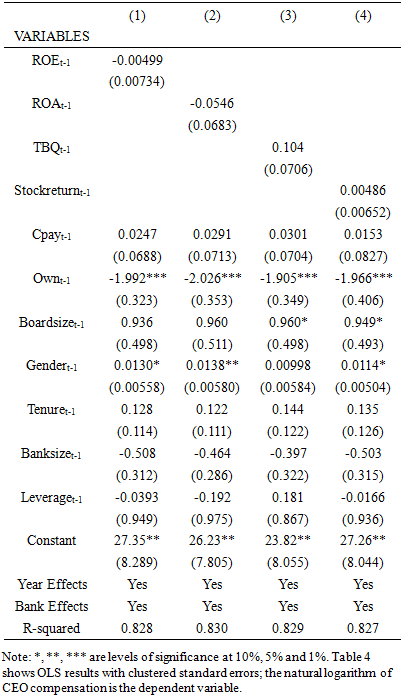

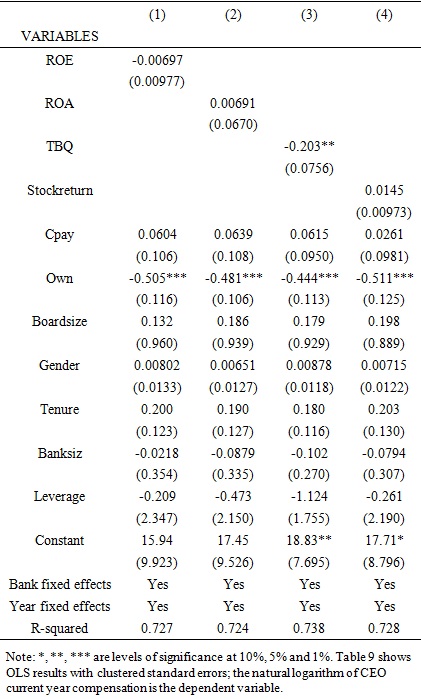

- The study results in Table 3 column 1 show a negative coefficient for that return on equity(ROE), while column 2 shows a positive coefficient for return on assets(ROA). The coefficients for return on equity and return on assets are all insignificant. The results suggest that bank profitability does not affect CEO cash pay in contrary to hypothesis 1b. Furthermore, Table 3 results in column 3 show a negative sign of the Tobin Q(TBQ) coefficient significant at 5% statistical level. In addition, Table 3 column 4 shows an insignificant relationship between bank stock returns and CEO compensation. Overall, Table 3 results show that both market measures of bank performance and accounting measures of bank performance are not associated with CEO compensation.

|

|

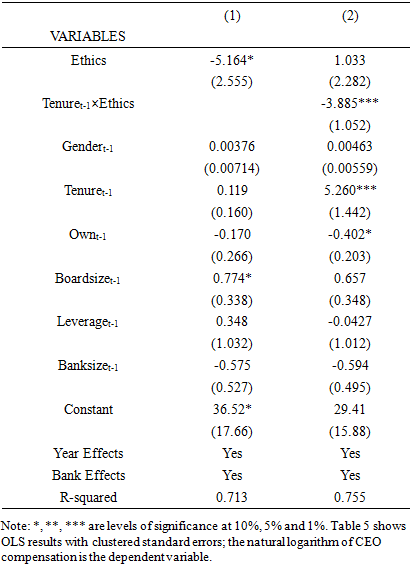

4.2. CEO Ethics and CEO Compensation

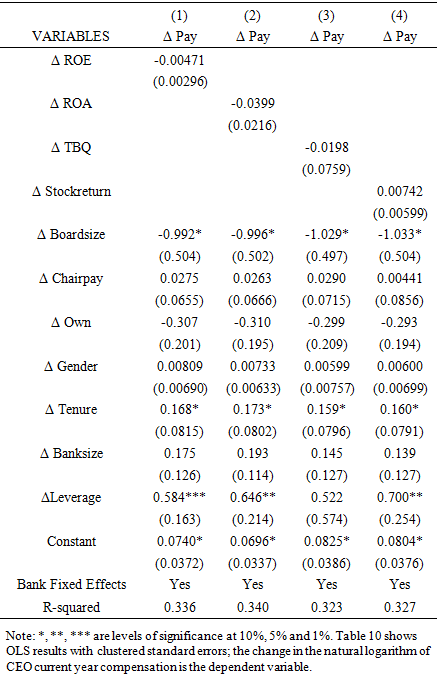

- The study reports the results for CEO ethics and compensation relationship in Table 5. Table 5 results in column 1 show the expected negative sign on the coefficient for ethics; the negative coefficient is significant at 10% statistical level. The study evidence suggests that the degree of the CEO’s ethical behavior has predictive power on the amount of cash compensation. The study further tests the interaction effects of CEO ethics and tenure on CEO pay using the lagged bank performance measures and reports the results in Table 5 column 2. The results in Table 5 column2 show a negative coefficient for the interaction variables (Tenuret-1×Ethics) significant at 1% statistical level. The results support hypothesis 4 that the moderation of tenure and CEO ethics negatively influences CEO pay. The study findings suggest that an increase in the term of office for an ethical CEO reduces the incentive to expropriate rent from banks through excessive compensation. The coefficients for tenure in Table 5 column 2 is significantly positive, suggesting that an increase in tenure for an unethical CEO creates conditions for the CEO to manipulate the board and get excessive cash pay. This relationship reconciles the mixed results in the agency literature on the association between tenure and CEO pay. However, another plausible economic interpretation could be that ethical CEOs with a long term horizon in the business may opt for less cash compensation and more equity compensation, which aligns their wealth with the business performance. In the same vein, the study extrapolates that unethical CEOs with long tenures may use managerial power to get more cash compensation, which does not link their wealth with long term business performance. If this argument is valid, it means that unethical long-serving entrenched CEOs have more incentives to shirk performance without facing disciplinary actions from the board for poor performance.

|

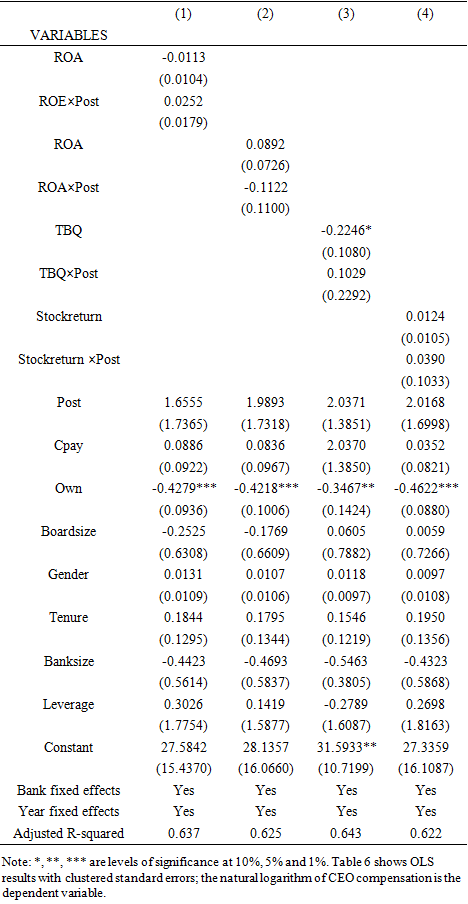

4.3. Corporate Governance Code and Pay for Performance

- The paper tests the impact of the corporate governance impact on CEO pay and bank performance relationship using the exogenous shock from the enforcement of the Corporate Governance Code for Banks and Discount Houses (CGCBDH) 2014. The expectation is that the new corporate governance code strengthens the governance systems in banks and hence a significant relationship between CEO pay and bank performance. The study uses the year 2014 as the policy year and interacts the policy year (Post) with the performance variables. The results shown in Table 6 in all columns show that the interaction of performance and Post does not have any significant relationship with CEO pay for all measures of bank performance. Furthermore, the results in Table 6 show similar results for corporate governance variables from the previously reported findings. The study evidence in Table 6 suggests that the new corporate governance code launched in 2014 did not bring any meaningful contribution towards aligning CEO cash pay with bank performance.

|

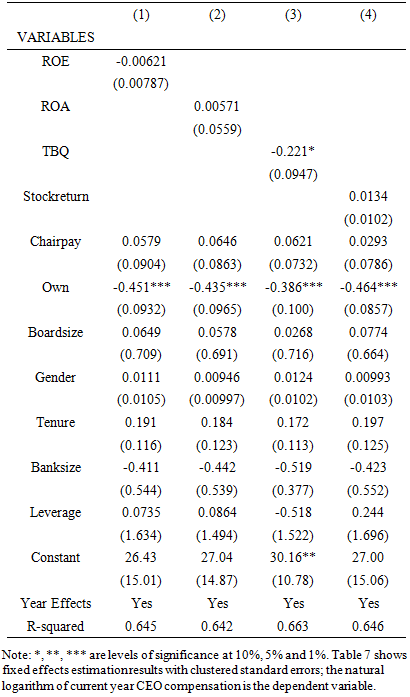

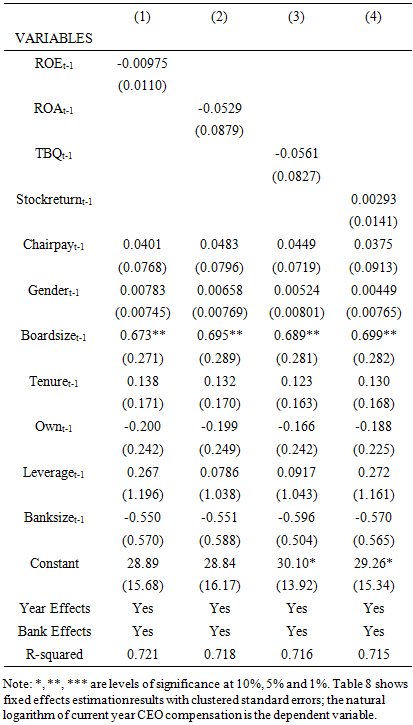

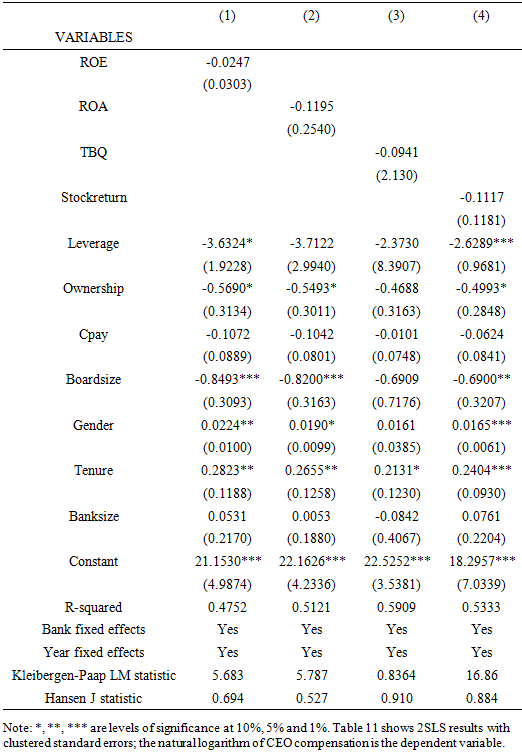

4.4. Robustness and Endogeneity

- I cross-check the validity of our OLS results using the fixed effects estimation. Even though the study use bank fixed effects to deal with omitted variables bias, there is a need for a panel data model with control for other time-variant characteristics. Considering that the study has controlled for time effects and bank effects, the results should be comparatively the same. The study reports the results in Table 7 and Table 8. The study results using fixed effects estimation in Tables 7 and Table 8 are similar to those obtained using the OLS estimation in prior findings. The results suggest the previously reported results are not affected by heterogeneity effects.

|

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

- The study examines the effect of bank performance and CEO ethics on CEO cash remuneration using a sample of listed Nigerian banks covering the period between 2006-2016. The study results in agreement with other studies show that there is no association between bank performance and CEO compensation. The plausible explanation of the findings is that cash compensation is usually set as a hygiene factor to retain the CEO skills and not as a reward for hard work or to motivate performance, which is consistent with agency literature, which ties firm performance to non-cash compensation. The impact of CEO ethics on compensation is more robust for long-tenured managers as compared with short term contracted managers. The intuition behind this result is that the more time the manager spends in the business, the more influence exerted on the firm’s corporate governance policies and board of directors. On the contrary, the study findings show that unethical bank CEOs are likely to be entrenched and to expropriate rent through excessive cash compensation as their tenure increases. The study evidence shows that board size, CEO ownership, and leverage are negatively related to CEO cash pay after controlling for endogeneity. The study shows that the presence of females on the board positively contribute to CEO compensation. An insignificant effect of bank size on cash compensation is established using two alternative measures of bank size. The study has some limitations that can be addressed by future researches. Firstly the sample size is relatively small due to the opacity of company disclosures of executive compensation. A higher sample size may increase the power and reliability of the results. Secondly, the study focuses only on cash compensation due to data limitations; there is hope that companies are going to become transparent and publicly disclose all forms of executive payments in bank financial statements. The study results have some policy implications for the regulators, board of directors, and other stakeholders. Firstly the study recommends corporate boards to consider CEO ethics as one of the factors for hiring, renewing, or extending the employment contracts for CEOs.On top of a legal environment which protects shareholders’ wealth from rent extraction by unethical CEOs, corporate boards have to play a monitoring oversight role by considering the CEO ethics seriously when hiring or extending the employment contracts of CEOs. There is a need for ethical awareness among board members spear led by the regulators to reform CEO ethical behaviors to avoid destructive scandals in the future. This is important as the CEO's ethics does not only affect shareholders and depositors but the entire fragile banking industry, which also affects the government through bailout packages to save the 'too big to fail' banks from collapse and to rescue the economy from shrinking. Also, the study recommends stronger institutions than influential individuals in the banks that borrow power from legal frameworks to enforce tightly knit corporate governance systems that close all loops for manipulation by unethical long-serving managers. Also, the study recommends the board of directors to use performance-based reward systems to motivate hard work and value increasing activities that benefit shareholders and other stakeholders. In view of the study results, I recommend boards to complement the internal governance mechanisms by issuing more leverage since it is a robust external governance device that can be used to monitor manager activities. Furthermore, I recommend the Nigerian central bank to increase the monitoring of banks and encourage disclosure of all compensation for the CEO. The central bank can encourage banks to increase their board sizes to strengthen firms' corporate governance systems. Since tenure and pay relationship is positively significant, The study recommends the regulators to limit CEO tenure to improve corporate governance in the banking industry. Lastly, I recommend future researches to study the determinants of CEO compensation using cross country studies. Cross country studies that compare emerging markets and developed markets may increase our understanding of CEO pay in greater detail.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML