-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2020; 10(2): 69-81

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20201002.03

Effects of the Nigeria Land Borders Closure on Benin Economy Measured from an Input-Output Model

Raïmi Aboudou Essessinou 1, 2, Guy Degla 1, Laurent Mahounou Hounsa 2

1Institute of Mathematics and Physics, University of Abomey-Calavi (UAC), Benin

2National Institute of Statistics and Economy Analysis (INSAE), Benin

Correspondence to: Raïmi Aboudou Essessinou , Institute of Mathematics and Physics, University of Abomey-Calavi (UAC), Benin.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In this paper, the impact of Nigerian border closure on the Benin economy is analyzed using an Input-Output (IO) model to detail the interrelations between sectors and basing on the multipliers of the Social Accounting Matrix (SAM). Our simulation results show that the closure of Benin-Nigerian borders has a negative impact on the Benin economy with respect to its total exports. The prolonged closure of Nigeria's borders with Benin results in a drop in customs revenue which could slow down economic growth. Moreover, an additional public expenditure policy in support of agri-food industries could improve purchasing power and household income. In summary, the results of this paper enable us to stress that the impact of a trade restriction policy implemented by Nigeria is not underestimated by the countries that share some borders with Nigeria.

Keywords: International Trade of Goods, Nigeria Land Borders Closure, Simulation and Impact Analysis

Cite this paper: Raïmi Aboudou Essessinou , Guy Degla , Laurent Mahounou Hounsa , Effects of the Nigeria Land Borders Closure on Benin Economy Measured from an Input-Output Model, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2020, pp. 69-81. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201002.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

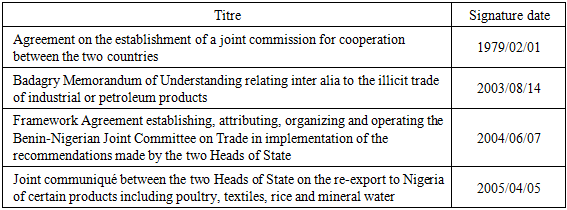

- The daily political and economic history of trade relations between Nigeria and its neighbors recalls many evils such as border disputes, fraudulent trafficking of goods, the development of counterfeiting and competition from cheaper foreign products that are likely to gangrene the flow of trade between Nigeria and its neighbors. On the one hand, this situation sometimes attracts the attention of Nigerian political and economic decision makers on the security issues of their borders and on their political stability in the search for offering real assets for the development of Benin-Nigeria trade. On the other hand, the effects of the evolution of Nigeria's economic growth on Benin's economic growth is very noticeable. Indeed, there is a cointegration relationship between the logarithm of the growth rates of the two economies. "A one percent (1%) increase in the growth rate in Nigeria goes hand in hand with an increase in that of Benin of 0.14% in the short term and 0.52% in the long term" [4]. As a transit country in West Africa for the hinterland countries, Benin has constantly striven to maintain good relations both with its progressive neighbors in the North (Burkina Faso, Niger) and with Nigeria (at East).Historically, despite Nigeria's trade restrictions vis-à-vis Benin, products banned by Nigeria have remained in informal trade between the two countries, but have adapted over time. So, since 1999, Benin has signed several trade agreements that have helped to strengthen trade relations with the rest of the world. Although Benin has a long tradition of trade with West Africa, its trade relations are more intense with Nigeria which has a strong economic influence on it. This situation is reflected by the fact that successive Governments of Benin could not define an economic policy without taking into account the measures taken by Nigeria. This tradition has led Benin to maintain some good trade cooperation with Nigeria through several trade agreements, the most recent of which are presented in the Table 1.

|

2. Theoretical Model and Methodology

- Different sources of accounting data can be used to calculate multipliers. The model we use in this paper is static and of type Input-Output (I-O) using accounting data to detail the interrelations between sectors [1].

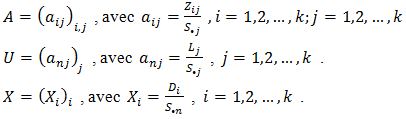

2.1. Presentation of the Model

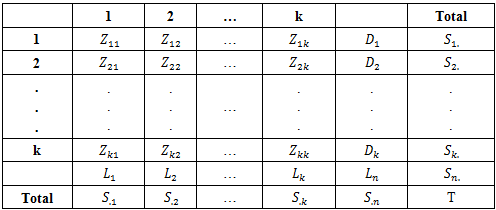

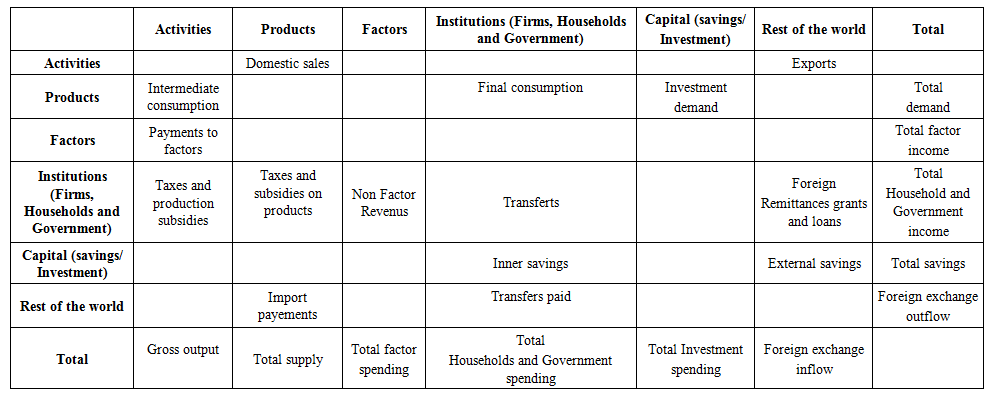

- The closure of Nigerian borders impact's analysis is based on a decomposition model of the Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) multipliers. "A SAM is a comprehensive synoptic table representing the economy-wide database recording data on transactions between economic agents in a certain economy during a certain period of time [1]. It integrates the production flows by business sector, the factor remuneration factor and the income and expenditure accounts of the different economic agents [5]. It mainly uses the results of the national accounts, notably the "Table of Employment Resources" and the "Table of Integrated Economic Accounts". It therefore presents the structure and interrelations of the economy at a given base year. It has the advantage of filling the demand for simulation and trend analysis in a context of lack of data over a long period. The SAM can be presented in aggregated form ("Macro SAM") and disaggregated (the "Micro SAM"). The macro SAM gives an aggregated view of the economy's cash flow and provides a single total for each account without any details about its content. Combining the descriptions made in [1], [2] and [12] the macro SAM is presented in the Table 2.

| Table 2. Basic macro SAM |

|

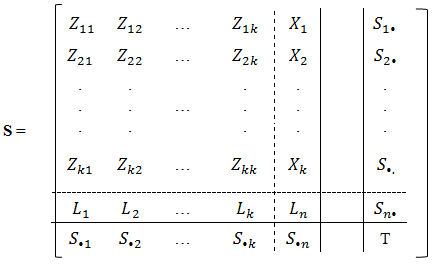

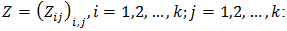

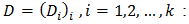

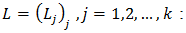

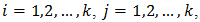

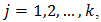

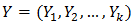

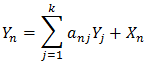

Let adopt the following notations:

Let adopt the following notations: the

the  matrix of endogenous accounts

matrix of endogenous accounts the

the  matrix of exogenous accounts.

matrix of exogenous accounts.  the

the  matrix of « leaks » for exogenous accounts.Thus, we obtain the following accounting relation:

matrix of « leaks » for exogenous accounts.Thus, we obtain the following accounting relation: | (1) |

| (2) |

the matrix

the matrix  of the technical coefficients of the endogenous accounts obtained in dividing each term

of the technical coefficients of the endogenous accounts obtained in dividing each term  for

for  by

by  the matrix obtained from the matrix

the matrix obtained from the matrix  by dividing each term

by dividing each term  for

for  and by

and by  the matrix obtained from the matrix

the matrix obtained from the matrix  by dividing each term

by dividing each term  by

by  that is to say:

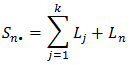

that is to say: Moreover, we pose

Moreover, we pose Since by construction of the SAM, the row totals are equal to the column totals that is to say

Since by construction of the SAM, the row totals are equal to the column totals that is to say  Let define

Let define  by

by  where

where  We adopt the same theoretical working hypotheses as those of Lorenzo Giovanni Bellù [11], namely:a. the coefficients

We adopt the same theoretical working hypotheses as those of Lorenzo Giovanni Bellù [11], namely:a. the coefficients  are considered fixed: this means that the average expenditure coefficients for each account should be calculated on the basis of the SAM, as parameters that also reflect changes in marginal expenditures;b. the relationships between endogenous and exogenous variables are linear (assumption of no substitution between different inputs and factors for all sectors of production and between different end products for all institutions);c. each exogenous expenditure takes the form of a supply of goods and services from the economic system, in other words, the economic system will not be constrained;d. prices of goods and services are not changed due to the impact of changes in exogenous demand (fixed price assumption).Thus, on the basis of these working hypotheses, we thus obtain from the accounting relation (1) the relation (3) below:

are considered fixed: this means that the average expenditure coefficients for each account should be calculated on the basis of the SAM, as parameters that also reflect changes in marginal expenditures;b. the relationships between endogenous and exogenous variables are linear (assumption of no substitution between different inputs and factors for all sectors of production and between different end products for all institutions);c. each exogenous expenditure takes the form of a supply of goods and services from the economic system, in other words, the economic system will not be constrained;d. prices of goods and services are not changed due to the impact of changes in exogenous demand (fixed price assumption).Thus, on the basis of these working hypotheses, we thus obtain from the accounting relation (1) the relation (3) below: | (3) |

| (4) |

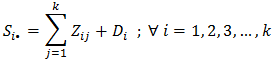

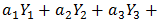

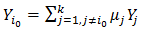

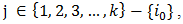

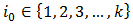

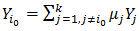

2.2. Theoretical Solution of the Model

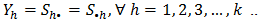

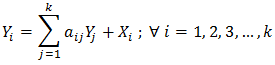

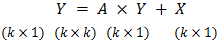

- The present system presented by the relation (3) has k unknown variables and k linear equations in the variables. Using matrix algebra, the proposed model can be written as follows:

| (5) |

and

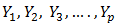

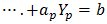

and  (i)- We call linear equation in variables (or unknowns)

(i)- We call linear equation in variables (or unknowns)  any relationship of form

any relationship of form

where

where  and

and  are real numbers given.(ii)- A system of n linear equations with p unknowns is a list of n linear equations.(iii)- A solution of the linear system is a list of p real numbers

are real numbers given.(ii)- A system of n linear equations with p unknowns is a list of n linear equations.(iii)- A solution of the linear system is a list of p real numbers  (a p-tuple) such as if we substitute

(a p-tuple) such as if we substitute  for

for  for

for  etc., in the linear system, we obtain equality. The set of system solutions is all of these p-tuples.Theorem 1. ([10], Theorem 1) A system of linear equations has either no solution, a single solution, or an infinity of solutions.Definition 2. ([10], Definitions 35, 36)(i) - Let

etc., in the linear system, we obtain equality. The set of system solutions is all of these p-tuples.Theorem 1. ([10], Theorem 1) A system of linear equations has either no solution, a single solution, or an infinity of solutions.Definition 2. ([10], Definitions 35, 36)(i) - Let  be a vector

be a vector  space and let

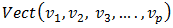

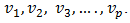

space and let  be a finite family of vectors of

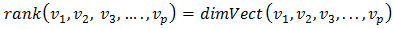

be a finite family of vectors of  The rank of the family

The rank of the family  is the dimension of the vector subspace

is the dimension of the vector subspace  generated by the vectors

generated by the vectors  In other words,

In other words,  .(ii) - The rank of a matrix is defined as the rank of its column vectors.Theorem 2. ([10]) A square matrix of size n is invertible if and only if it is of rank n.Proof. See Theorem 27 in [10].Proposition 1. ([10])The following assertions are equivalent:(i) Matrix A is invertible.(ii) For any second member B, the linear system AX = B has a unique solution X given by X= A-1B.Proof. See Corollary 1 and Theorem 11 in [10].Proposition 1. If it does not exist

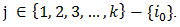

.(ii) - The rank of a matrix is defined as the rank of its column vectors.Theorem 2. ([10]) A square matrix of size n is invertible if and only if it is of rank n.Proof. See Theorem 27 in [10].Proposition 1. ([10])The following assertions are equivalent:(i) Matrix A is invertible.(ii) For any second member B, the linear system AX = B has a unique solution X given by X= A-1B.Proof. See Corollary 1 and Theorem 11 in [10].Proposition 1. If it does not exist  such as

such as  where

where  is a real parameter for all

is a real parameter for all  then the system (5) has a unique solution.Proof. Suppose that there does not exist

then the system (5) has a unique solution.Proof. Suppose that there does not exist  such that

such that  with

with  given real numbers,

given real numbers,  Then, in system (5), no equation is a linear combination of the others. The column vectors of the system are therefore linearly independent. Therefore, the vector subspace generated by the column vectors is of dimension

Then, in system (5), no equation is a linear combination of the others. The column vectors of the system are therefore linearly independent. Therefore, the vector subspace generated by the column vectors is of dimension  thus the matrix

thus the matrix  is of rank

is of rank  and consequently,

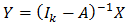

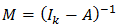

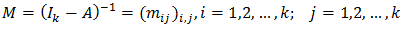

and consequently,  being a square matrix, it is invertible according to Theorem 2. Using Proposition 1, we thus obtain that the system (5) admits a unique solution given by:

being a square matrix, it is invertible according to Theorem 2. Using Proposition 1, we thus obtain that the system (5) admits a unique solution given by:  | (6) |

the identity matrix of order

the identity matrix of order  Remark 1. The system solution (5) is the product of the inverse matrix

Remark 1. The system solution (5) is the product of the inverse matrix  and the exogenous vector X [11].Definition 3.The matrix

and the exogenous vector X [11].Definition 3.The matrix  is called the multiplier matrix of the SAM.Remark 2. The matrix M allows analytically to transmit the effects of exogenous shocks to the economic system through a multiplication process of impacts that follows an iterative channel of production, distribution and resources using [11]. In general, the matrix element

is called the multiplier matrix of the SAM.Remark 2. The matrix M allows analytically to transmit the effects of exogenous shocks to the economic system through a multiplication process of impacts that follows an iterative channel of production, distribution and resources using [11]. In general, the matrix element  shows the change in monetary units of the total receipts i under a unit variation of the exogenous receipts of the account j.

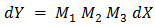

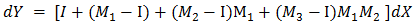

shows the change in monetary units of the total receipts i under a unit variation of the exogenous receipts of the account j.2.3. Decomposition of SAM Multipliers

- The matrix of multipliers makes it possible to understand the impact of the unit variation of the exogenous accounts on the totals of all the other accounts. For more transparency, and in particular to examine the nature of the link in the economy that leads to these results, it is possible to break down the SAM multiplier. We propose decomposition into three multiplicative components as presented by Jeffery Round [9].

| (7) |

are all matrices of "multiplication". As described by Jeffery Round [9], these decomposition matrices are interpreted as follows:

are all matrices of "multiplication". As described by Jeffery Round [9], these decomposition matrices are interpreted as follows:  represents the effect "within the account", ie the effect of the unit variation of exogenous accounts on themselves;

represents the effect "within the account", ie the effect of the unit variation of exogenous accounts on themselves;  captures "cross" (or "spillover") effects, ie the effect of the unit variation of the exogenous accounts on other accounts without adverse effects and

captures "cross" (or "spillover") effects, ie the effect of the unit variation of the exogenous accounts on other accounts without adverse effects and  shows the multiplier effects due to the full circular flow these are the effects "between accounts", after extracting the multipliers "within the account". It is interesting to determine the relative magnitude of these multiplier components in order to better understand the nature of the link and to identify duality zones in the economy. The impact of the exogenous shock is therefore simulated using the following relation:

shows the multiplier effects due to the full circular flow these are the effects "between accounts", after extracting the multipliers "within the account". It is interesting to determine the relative magnitude of these multiplier components in order to better understand the nature of the link and to identify duality zones in the economy. The impact of the exogenous shock is therefore simulated using the following relation: | (8) |

| (9) |

3. Application and Discussion of Results

- The macroeconomic methodological analysis is based on simulation hypotheses given by scenarios to understand the impact of Nigeria and Benin land borders closure on the Benin economy.

3.1. Data and Accounting Framework

- The accounting framework is based on the Social Accounting Matrix (SAM). The SAM establishes the interrelationships between sectors of the economy and facilitates the measurement of shocks from one sector to another.We use the SAM of 2013 built by the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Analysis (INSAE) of Benin, with the support of West African Economics and Monetary Union (WAEMU) commission as has said INSAE [7]. The SAM 2013 includes 23 branches and 23 types of products and services used or produced in the economy production process. In total, four types of economic agents intervene in the economy through the model. These are: Enterprises (firms), Households (in turn subdivided into six categories: Public employees, Formal private employees, Informal private employees, Primary workers (farmers, pastoralists, fishermen, etc.). The rest of the world is divided into fourteen (14) destinations depending on the prospects for analysis, and this disaggregation highlights Benin's economic relations with the WAEMU countries, Nigeria, Ghana, the other ECOWAS countries, China, the United Sates or America (USA), the European Union (EU) and finally the other countries of the world. In summary, the models based on the multipliers of the 2013 SAM are based on the following standard assumptions:a. prices are assumed to be fixed, which implies the existence of an excess of production capacity in the economy.b. the average spending propensities of the endogenous accounts are constant.c. the production function and the factor endowments are given for a period.Under these working hypotheses, the model was used to analyze in particular the effects of exogenous shocks (from trade with Nigeria and injections of exogenous public resources) of demand on endogenous accounts.As a prelude to the simulation exercises, a treatment was done on the 2013 SAM to estimate the training effects of the different components identified in this SAM, through the multipliers. The synthesis of training effects is presented in the appendix.Remark 3. By construction, in the SAM 2013, no line is a linear combination of others lines.

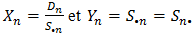

3.2. Hypotheses and Simulation Scenarios

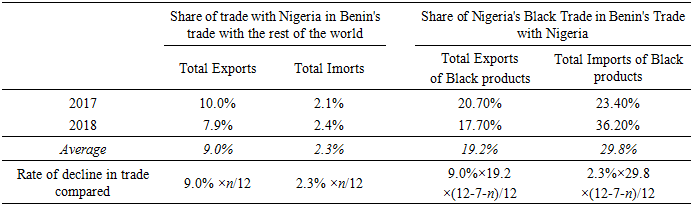

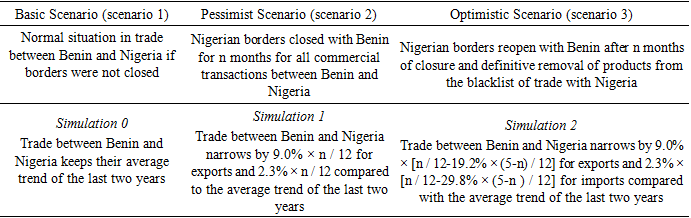

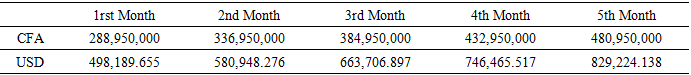

- The simulations were made taking into account the average trade trend between Benin and the rest of the world over the last two years. The contraction levels of the volume of trade is calculated in proportion to the number of months the land borders Benin-Nigerian are closed. The data given parameters for calculation are presented in Table 4.

|

|

|

3.3. Discussion of Simulation Results

- The impacts are measured on the one hand by the training effects highlighted by the SAM multipliers and on the other hand by the variations induced by the shocks.

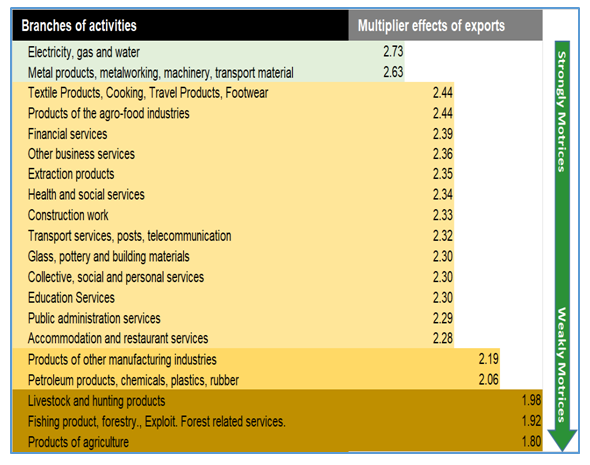

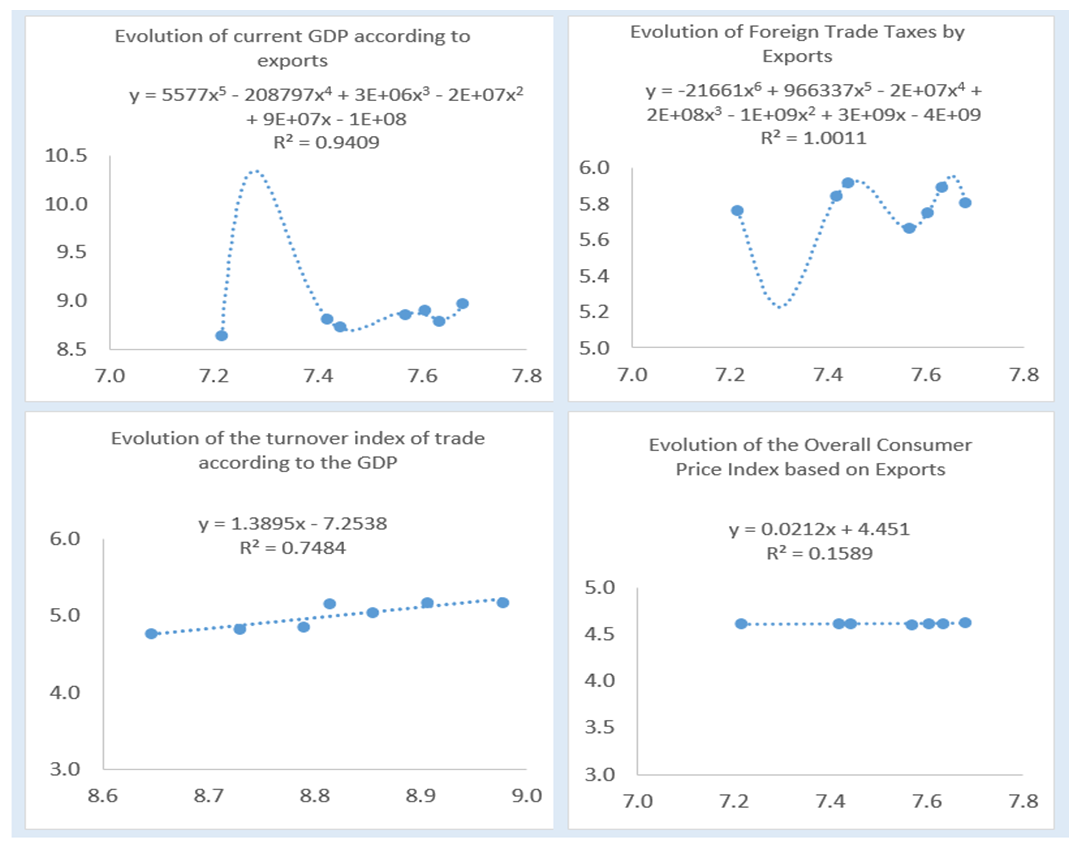

3.3.1. Analysis of Multiplier Effects for Benin Partners International Trade and the Economic Branches

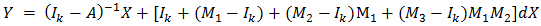

- ο EXTERNAL TRADE: WHICH PARTNER COUNTRIES IMPULSE MORE?Benin's trade relations with its main partners are marked by a strong disparity of the training effects between the export partnership and the import partnership. The Figure 1 presents the multiplier effects for exports and imports.

| Figure 1. Multiplier effects of Benin's trading partners |

| Figure 2. Multiplier of exports of different branches of the economy |

| Figure 3. Multiplier of imports of different branches of the economy |

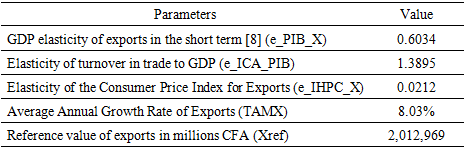

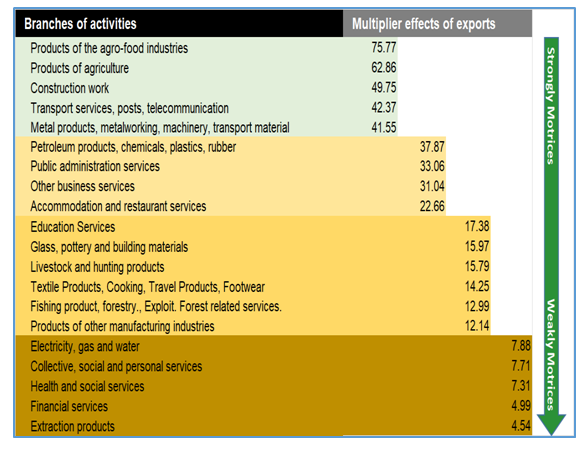

3.3.2. Prolonged Closure of Nigerian Land Borders: Benin Exports are Continuously Degraded

- Under the assumptions mentioned above, the closure of Benin-Nigerian borders has a negative impact on Benin's total exports to the rest of the world. Indeed, this closure results in a decline in the total value of exports. This fall from 0.457 times corresponding to the reference value to reach 0.420 times in the optimistic case and 0.419 times in the pessimistic case after five (5) consecutive months of closing the Nigerian land borders. It should be noted that the decline recorded for the optimistic scenario is slightly greater than that recorded for the pessimistic scenario. The simulation results is illustrated by Figure 4.

| Figure 4. The simulated trend of Benin's total exports by scenario |

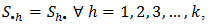

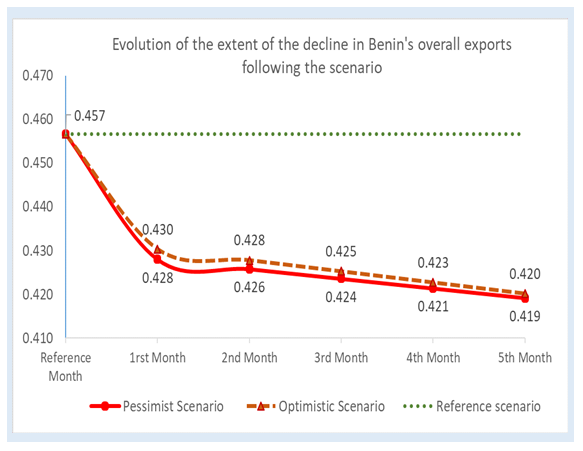

3.3.3. Immediate Impact of Prolonged Nigerian’s Land Borders Closure: Decreased Customs Revenue Risks to Slow Economic Growth

- The analysis in the Figure 5 below shows that neither the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) nor the Foreign Trade Taxes have a non-linear relationship with exports. The observed relationships are polynomial with very strong correlations. On the other hand, GDP is linearly related to the turnover index of trade, with an estimated correlation coefficient of 75%. Also, exports seem to explain the consumer price index linearly, but with a relatively weak correlation (15%).

| Figure 5. Correlation between macroeconomic aggregates and trade |

|

|

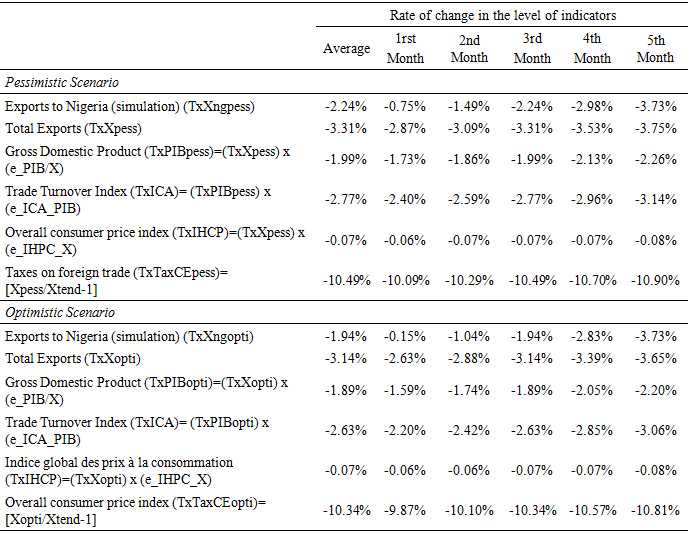

3.3.4. Measures to Support Business People: Can Increased Public Expenditure Improve the Situation ?

- In view of implementing the recommendations of the pineapple and market garden sector stakeholders on the need to cover the additional burden, the interventionist policy of the Government in favor of agri-food industries has a positive effect on the level of resources. In fact, as it is presented in Table 9, in perspective of strengthening the on-site processing of perishable products following the closure of the Benin-Nigerian land borders over the period from August to December 2019, government spending in favor of agri-food industries results in an increase of revenues from production and taxes over the simulation period.Resources from tax recoveries increase: On average, revenues are derived from "non-deductible VAT" (0.18%), "Other taxes on products" (0.10%), "Taxes on exports" (0.14%), "Taxes on imports" (0.18%), "Current taxes on income and capital" (0.08%). The fall in total local production is slowing down for the import-intensive industries: By a driving effect mechanism, an additional contribution of public expenditure in the agri-food industries generally leads to a slowdown in the decline in the production of highly impulsive branches for imports. The total output of the branches is reviving and therefore growth would resume in all four fifths of the branches of the economy. The main branches with higher production are: "Other manufacturing products" (+ 0.46%), "Other business services" (+0.14%) "Agribusiness products" (+0.12%). However, overall industry branche output could maintain its rate of deterioration with an average decline of 1.28%. This drop could be led by the branches "Metal products, metalworking, machinery, transport material" (-0.72%), "Construction work" (-0.33%), "Glass, pottery and building materials" (-1.11%) which, on average, would record a deterioration in the level of their production.Additional Government expenditures in support of Agro-Food Industries could improve household purchasing power and income: The results of Table 9 show that the substantial gain to be expected in Primary and Tertiary production following additional Government expenditures in the industry products sector agribusiness "could result in improved business and transport activities. Thus, this improvement could contribute, on the one hand, to improve the purchasing power of households through a fall in consumer prices because of the supply-supply multiplier and, on the other hand, the recovery of 18% of household incomes, particularly "informal private employees", "primary workers (farmers, pastoralists, fishermen, etc.)" and "non-agricultural self-employed and employers".

|

3.3.5. How Important is Beninese Market for the Southern States of Nigeria

- Benin and Nigeria have always maintained trading relations through economic markets. The city of Lagos, Nigeria's former economic capital, has a population of more than 13 million, with a seaport and a lagoon port. It has a huge consumer market that is the pride of people and foreigners. Southern states (Lagos, Badagri, etc.) in Nigeria benefit from Benin-Nigeria's cross-border mobility dynamics, urban and rural integration, but also from the porous land borders maintained by corruption. The markets of Dantokpa and Ouando in the heart of the two major cities of Benin: Cotonou and Porto-Novo, serve as a platform for economic exchange between Benin and these southern states of Nigeria. The proximity of the two Beninese markets with the southern states of Nigeria is an opportunity for market accessibility and also facilitates Nigerian supplies. The two major Beninese markets (Dantokpa and Ouando) represent a space of economic exchange with the southern states of Nigeria, products coming from inside and outside (from the subregion and from Europe).Nigeria allows entry of foreign rice only through its ports, where it has imposed a 70% tax since 2013. The goal is not only to increase revenues, but also to encourage local production. rice. But smugglers take advantage of the fact that it is cheaper to import rice into Nigeria's neighboring countries to grow their business. According to the Nigerian Ships and Ports website, Benin country lowered its tariffs on rice imports from 35% to 7% in 2014. Neighboring Benin then recorded an astronomical rise in rice imports that 11.5 million people cannot consume. Thus, through these two markets, rice is making its way to Nigeria to fill the local production gap of a country of nearly 200 million people. Following the border closures in Rivers State, southern Nigeria, some traders from the Rice Depot section of the Mile 1 Market in Port Harcourt packed their bags and returned home. The dramatic land borders closure has not given the people of the states of Nigeria time to make stock. As a result, prices have also gone up. Foreign rice is now 60% more expensive, while locally produced rice has increased by almost 100%. Benin has been for decades, a market no less negligible for the southern states of Nigeria, because of its geographical position and urban density.

3.3.6. What Nigeria Gains and Loses from the Prolonged Closure of Its Land Borders

- The impact of this land borders closure has been felt positively in some sectors and negatively in others.According to a BBC New Africa publication of October 31rst, 2019, Nigerian Customs chief recently told parliamentarians that tax revenues had increased as goods destined for Benin arrived at Nigerian ports. He noted that one day in September 2019, a record 9.2 billion naira ($ 25 million) was collected, which had "never happened before". He said: "After the border closed and since then, we have maintained an average of about 4.7 to 5.8 billion naira a day, which is much more than before."The simulations show that closing the borders until the end of December 2019 is expected to result in a 1.02% increase in Net Income received by the Federal Government of Nigeria. According to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) [13] reports, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by 2.28% (yoy), in real terms, in the third quarter of 2019. Compared to the second quarter of 2019, which recorded a growth rate of 2.12%, the third quarter of 2019 represents an increase of 0.17%. On a quarterly basis, real GDP grew by 9.23% at the third quarter of 2019.In addition, according to Nigeria's NBS, the total value of capital imports into Nigeria, amounting to $ 5,367.56 million in the third quarter of 2019, is decreased by 7.78% compared to the second quarter of 2019. Similarly, the purchasing power of households has weakened. In fact, the inflation rate that began an expansive phase since the borders closed rose to 11.61% in October 2019. According to the analysis of the Nigeria’s NBS, the price increase is due to food products mainly due to food shortages caused by the ongoing closure of the Nigeria land borders and the impact of unusually heavy rainfall on the harvest. The rising inflation rate could mark the beginning of a new cycle of poverty in Nigeria and the region. According to IMF forecasts, the inflation rate should be 11.3% in 2019 and 11.7% in 2020, but due to the border closure situation, inflation could increase further in percentage point of 0.82 in November 2019 and 0.89 in December 2019.

4. Policy Implications

- The interventions should lead to the establishment of an ambitious reform program in order to boost the productivity of small farmers and promoting the development of a domestic agri-food industry in which foreign companies can be invited to invest.

4.1. Possible Measures for Benin Economic Independence vis-à-vis of Nigeria

- Benin country should better, in the:(i) short and medium terms, strengthen the development of the agricultural sector through value chains of innovative agri-food industries for products with high potential in trade with Nigeria that are: pasta, milled and semi-milled rice, nuts and fine of palm, fat and vegetable oil, palm oil, cottonseed oil, fresh apple, banana, tomato, pineapple,(ii) medium term, raise awareness and strengthen the capacity of Beninese economic operators to find other outlets in the sub region, for products that weigh more in exports to Nigeria: rice (17.1%), oils sunflower or cotton (12.1%), palm oil and its fractions (10.3%), animal or vegetable fats and oils (3.2%),(iii) medium term, set up a shared-cost fund to reinforce the construction of infrastructures on value-added chains (storage, conservation, processing, packaging, cold chain) in order to reinforce the consumption of local products,(iv) long term, remove the smuggling trade with Nigeria,(v) long term, deregulate the seed and fertilizer distribution sector and put in place an effective system of subsidies for farmers,(vi) long term, create a risk sharing guarantee fund to reduce the risk of commercial banks lending to farmers,(vii) long term, make the agro-food value chain more efficient by bringing together agro-industrialists and agricultural producers in large industrial zones, the Basic Crop Treatment Zones (BCTZ),(viii) long term, set up a free zone consisting of the following countries: Togo, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Niger Senegal and Ghana for exports of goods from Benin to West Africa. Indeed, Benin's commercial potentialities at the level of trading partners such as Togo, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire and Niger are very important for products such as: pasta, milled rice and semi-milled rice, nuts and fine palm, fat and vegetable oil, palm oil, cottonseed oil, fresh apple, banana, tomato, pineapple, cotton fabrics.

4.2. Proposals to Improve Economic Exchanges of Benin

- Three approaches are proposed to improve external trade of Benin country. (a) The first approach: In the long term, Benin should create in the interior a monetary, legal and fiscal zone in which Nigerian economic operators could come to trade freely without exchange risk and with a flexible taxation aligned with that of Nigeria for certain activities. That could be more attractive for foreign Investors who are interested in the Nigerian market. This will position Benin as an entry platform to Nigeria and continue to make the country an attractive outlet for Nigerian economic operators.(b) The second approach: In the medium term, Benin should adjust its investment code with that of Nigeria by aligning its legal and regulatory framework with that of Nigeria.(c) The third approach: In the medium term, should strengthen the diplomatic policy of Benin's international trade in agricultural products.

5. Conclusions

- This paper point out that Benin's exports are more drawn by the secondary sector with stronger multiplier effects for the "Electricity, gas and water" and "Metal products, metalworking, machinery, transport material" branches. On the other hand, Benin's imports are drawn concomitantly by the three sectors of the economy. However, the secondary sector is predominant with the "Agribusiness Products" and "Construction Works" divisions.Despite the increased dependence on Nigeria, the low level of diversification and the low competitiveness of Benin's international trade with Nigeria, exit routes are possible. The results of the study show that Benin has enormous potential to develop with Nigeria and other countries in West Africa. However, Nigeria retains a great deal of weight and the adverse effect of Benin's export response to a shock on Benin economy is very significant because of its geographical proximity.The results of the study show that the closure of Benin-Nigerian borders has a negative impact on the level of total exports of Benin. Under the assumption of a temporary closure for the prohibited products only, it should be noted that the decline recorded is slightly greater than that recorded for the case where Nigeria maintained its position of permanent closure to all products from Benin. The prolonged closure of Nigeria's land borders with Benin results in lower tax revenues that could slow down GDP growth. The results analysis showed that the indicators of the economic activities could also plunge because of their positive correlation with the commercial exchanges. It should be noted that the decline is becoming increasingly pronounced if Nigeria maintains its position of closing its land borders over a relatively long period.By means of a training effect mechanism, an additional contribution of public expenditure in the agro-food industry globally leads to a slowdown in the fall in the production of highly impulsive branches for imports. The total output of the branches is reviving and therefore growth would resume in all four fifths of the branches of the economy.We also note that Benin's commercial potentialities at the level of trading partners such as Togo, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire and Niger are very important. Thus, these countries could constitute a free zone for exports of goods from Benin to this list of countries one can at the limit add Senegal and Ghana.In summary, the results of this paper highlight the vitality of Benin's foreign trade in West Africa and lead to stress that the impact of a trade-restrictive policy implemented by Nigeria is not undermined valued.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Analysis for the facilitation of access to the Social Account Matrix of 2013. Furthermore, our thanks go to all those who have contributed to the improvement of the quality of the paper. Special thanks to all the reviewers.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML