-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2019; 9(6): 282-288

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20190906.02

Foreign Aid for Trade, African Continental Free Trade, and Trade Volume: Does Foreign Aid Inflow Matter in West African Monetary Zone?

Chukwuemeka Amaefule, Okechuku Onuchuku, Ijeoma Emele Kalu, Akeem Shoaga

Department of Economics, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Chukwuemeka Amaefule, Department of Economics, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Does Foreign Aid inflow matter in West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ)? Data from World Bank were sourced from 1970-2017. This study examined the long-run impact of ODA on trade volume in selected WAMZ. The study adopted Shin, Yu, and Green-wood (2011) NARDL framework to study the implication of both increase in ODA inflow and decrease in ODA inflow. The study found that ODA has negative impact on trade in WAMZ. Specifically, both increase in ODA inflow and decrease in ODA inflow on trade in WAMZ were negative. However, the bound test showed that long-run relationship exist between ODA and trade in WAMZ. Also, the speeds of adjustment were negative and statistically significant at 5 percent. The result implies that dependence on ODA inflows could distort trade volume, in spite of the existing long-run relationship, ODA do not reduce cost of trade in WAMZ, hence the negative impact on trade. To achieve expanded trade growth, to improve the capacity of WAMZ to earn foreign exchanges, and to gain market share in the global trade, WAMZ should design policy to tap into its local raw materials, pursue inclusive and sustainable diversification. Lastly, WAMZ trade must be based on raw materials for both imports and exports until strategic and responsible attempts are taken to accelerate local productive capacity to produce and incentivise domestic capacity to trade at the global market.

Keywords: African Continental Free Trade Agreement, Aid for Trade, Trade robustness, Foreign Aid, and Non-linear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL)

Cite this paper: Chukwuemeka Amaefule, Okechuku Onuchuku, Ijeoma Emele Kalu, Akeem Shoaga, Foreign Aid for Trade, African Continental Free Trade, and Trade Volume: Does Foreign Aid Inflow Matter in West African Monetary Zone?, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 9 No. 6, 2019, pp. 282-288. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20190906.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The Washington annual meetings in October 14th-20th, 2019 set out five point robust global policy agenda which includes trade growth, independence of the central banking system, fiscal budgeting, structural reforms, and international cooperation on climate change etc. The IMF-Kristalina Georgieva effect clearly incites scholarly responses on the implication of trade tensions and trade wars on the global economic stability. Global economists are concern about the consequences of trade wars and trade tensions around the world. Particularly, the trade-war tariffs imposition between two largest economies of the world to the tune of $310bn tariff imposition on Chinese goods by the U.S. and the corresponding tariff imposition on U.S. goods by Chinese government to the tune of $110bn; Japan and South Korea trade tensions, and the Brexit have dampening effect of the stability of the global economy (Bowler, 2019). The transmission effects of these trade wars can be seen from the performances of the global subdued economic growth from 3.6 percent in 2018 has slowed to 3.3 percent in 2019. The 2020 growth forecast of 3.6 percent within the trade tension remains farfetched (IMF, 2019). In this study our focus is therefore on trade stability and growth in West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ). One way to assess the stability of global trade is by examining the extent to which foreign aid influences trade. The global imperativeness of foreign aid on improving trade has received major global attention. By assessing the impact of foreign aid on trade we try to clearly provide answers on the vexed issues raised by Kristalina Georgieva global policy concern on the implications of trade wars on global trade. It is fundamentally significant to recall that U.S. and China overtime has become a major donor country to Africa. Before we delve into the impact of foreign aid on trade in WAMZ, it is pertinent to assert that there are lots of empirical validity on the role of foreign aid to economic growth and development. However, the impacts of foreign aid on trade seem a brewing concern amongst scholars. Global attention is growing on the dual benefits of foreign aid for both the donor and recipient countries (Liu and Tang, 2017; Noh and Heshmati, 2017). The concern therefore is whether foreign aid inflows increase volume of trade in West African Monetary Zone? WAMZ trade is central to improve external reserves goal a core primary target in Macroeconomic Convergence Criteria (MCC). Thus, the studies on how increase in foreign aid inflows and decrease in foreign aid inflows impact on trade volume in WAMZ is quite missing in the literature? To properly situate this study it is germane to consider two policies such as Foreign Aid for Trade (AfT) and African Continental Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA). These trade policies are designed to accelerate trade in Africa by extension WAMZ namely Ghana, Gambia, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone. The present argument on foreign aid for trade (AfT) to facilitate trade and accelerate country’s income revolves around the potentials of foreign aid to directly reduce costs associated with multilateral trading that affects less developing economies’ capacity to trade globally. These identified costs are viz; “behind the border costs”: cost associated with production of goods to be exported; “between border costs”: cost associated with transportation costs and good freightage, and “at the border cost”: cost associated with tariffs and border processes for good exchanges (EU, 2017, OECD, 2006, WTO-OECD 2015). Cost-Reduction Target (CRT) focus on multilateral trade agreement between LDCs and developed countries, hence foreign aid arguably remain vital instrumentality to reducing multilateral trade cost (Alonso, 2016). The concept of Foreign Aid for Trade (AfT) has metamorphosed namely from 2005 Hong Kong Ministerial Conferences, 2005 Paris declaration on Aid effectiveness, Doha round process, and 10th October, 2006 WTO task force etc. Presently AfT constitute a major development cooperation policy thrust in WTO and OECD (OECD, 2006; WTO, 2008). Basically, the strategic activities of AfT includes; “provision of technical assistance, development of trade-related infrastructure, provision of assistance to private sector to exploit its comparative advantage, and creation of TRA-trade related adjustment which include trade policy and regulation, trade building productive capacity, and other trade related needs” (OECD, 2007, pp 44-45). Additionally, global concern on trade can be viewed from the strategic steps taken by UNCTAD. UNCTAD trade and development Report (2018) accentuates regional concern for trade facilitation as recipe for growth and development. The global policy document of UNCTAD heightens the urgency for policy-makers in developing and emerging economies to expedite actions to the emerging risks facing developing countries and the extant implications on the changing trade pattern of the global economy in the era of hyperglobalization. Basically, the UNCTAD report (2018) linked issues of globalization, inequality and growth with the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. In view to develop global trade links to reduce the current economic imbalance in the global economy. Thus, trade is essential for economic growth and development. Over and above AfT, African Union has recently implemented its trade policy called African Continental Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA). Local efforts to accelerate trade vary from country to country. Recently, African Union initiated a robust trade policy agenda called ACFTA. ACFTA is trade agreement for Africa. It was endorsed by 44 African leaders in Kilgali, Rwanda 2018. ACFTA promises amongst other significant objective designed to accelerate bilateral trade in Africa. ACFTA is in tandem with AfT to improve trade, and jointly AfT and ACFTA have trade deepening in Africa as a common goal in response to address trade deficits and balance of payment disequilibrium developmental challenges in sub-Saharan Africa. Specifically, ACFTA promises to raise the optimism of within border trade viz-a-viz bilateral trade in African continent to accelerate economic growth and development. ACFTA at full implementation could enhance Africa’s competitiveness. ACFTA is divided into thirty-two Articles. Specifically, general objectives, specific objectives and principles of the Articles are stipulated in Article 3, Article 4, and Article 5. The core underlying philosophy of ACFTA is to create a single market for Africa, deepen economic integration in line with the Pan-African Vision of “An integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa” enshrined in Agenda 2063 (ACFTA, 2019). UNCTAD (2018) states that ACFTA offers provides fulcrum for sustainable development and economic growth in the African economies. ACFTA from forecast can boost intra-African trade/GDP aggregate to $3.4 trillion (UN Economic Commission for Africa, 2018). In aggregate the agreement has manifold benefits such as viz; to establish a single continental market for goods and services with free movement of business contacts across Africa, to expand intra-African trade through adequate harmonization and coordination of trade liberalization and facilitation across Regional Economic Councils (RECs), to improve single market and integration process across Africa, to enhance competitiveness at the industry and enterprise level by exploiting opportunities for scale production, continental market access and better reallocation of resources (AfDB, 2018). In view of the imperativeness of global trade on growth and development, West African Monetary Zone; sub-regional bloc in Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), joined its African counterpart to sign into existence African Continental Free Trade Area (ACFTA) treaty arrangement. ACFTA is apt. The full implementation could accelerate and speed-up drivers of growth in Africa ceteris paribus. ACFTA is home grown idea on trade. ACFTA can foster productivity and stimulate the competitiveness frontier of the region thereby reduce trade deficit as well as correct balance of payment disequilibrium that erode the capacity of the region to foreign exchange earnings. The policy is strategically designed as a catalyst to the regional economic communities (RECs) recognized by AU. Particularly, in all of these trade policies, to what extent would these policies affect WAMZ? How can these trade policies improve WAMZ’s capacity to achieve macroeconomic convergence criteria (MCC)? MCC is fundamental for the adoption of common currency called ECO currency. Deepened foreign trade therefore improves the impetus of WAMZ to earn foreign exchanges which would by extension improve the external reserves of WAMZ. Thus, robust export trade is healthy to satisfy primary objective criteria of external reserves > 6 months import cover, and indirectly satisfy the reduction of imported based inflation and attainment of inflation ≤ 5% target etc (Saka, Onafowokan, and Adebayo, 2015).

2. Statement of Problem

- WAMZ MCC targets to achieve external reserves that will cover three months import remain fundamentally oblivion. In this paper, we therefore try to find the extent of foreign aid to improve trade in WAMZ. This study is important following the nexus between trade and external reserves. The question becomes can ODA inflows accelerate trade capacity of the region which in turn would improve WAMZ target on gross external reserves > 6 months imports. The major gap of this study is to determine the impact of increase and decrease in the ODA inflows on trade in selected WAMZ.

3. Research Objective

- The objective of this paper is to determine the impact of foreign aid (proxy by ODA inflow) into WAMZ trade (proxy by trade (% of GDP)) in selected countries Gambia, Ghana, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone.

4. Significance of the Study

- The import of this study revolves around the implication of foreign trade on external reserves (see Nteegah and Okpoi, 2017) and foreign trade links external reserves is required to sustain ECO currency union beyond 2020. Therefore understanding how trade volume is affected by ODA inflows would help WAMZ to foster sound policies framework required to insulate the region from disturbances emanating from ODA inflows.

5. Theoretical Literature

- McKinnon and Shaw (1973) hold in financial liberalization thesis that ease of cross border capital flow catalyses growth. And that financial repression is caused by excessive restriction or stringent conditions for finance to flow to its optimum use. Chenery and Strout (1966) revealed the importance of external finance in their two gap theory. They contend that due to shortage of capital in the developing countries to accelerate national development agenda, caused by savings-investment deficits, import-export deficit, and expanded to three gap theory i.e. taxes-revenue deficit, less developing countries ought to attract capital to cushion the low capital formation problems caused by savings. These theories opine that external capital is indeed helpful. To assess the importance of ODA it is imperative to examine the significance of ODA to trade in view of the policy concern in WAMZ.

6. Empirical Literature

- There is a robust contention on what role can and what role should global policy of aid take to fast-track development, and also closely debated issue amongst scholar is the vexed ambiguous findings on the effectiveness of Aid. Does ODA matter to improve trade in WAMZ? Adenauer and Vagassky (1998) reports that evidences of ODA on sub-Saharan countries provide little significant impact on export performances. Bhattara (2016) study posits that investment rather than aid contributes to growths in developing countries. The panel analyses further posits that exports tied to aid have been harmful for growth of recipient countries. Martinez-Zarzoso (2019) estimated 33 donor countries and 125 recipients employing structural gravity model found that development aid has a direct impact on donor exports and has an indirect positive effect on income levels in the recipient countries. Thus, the study found heterogeneous impact of development across selected countries. Papanek (1972) applied regression method, found positive ODA impact on growth for 34 countries. Singh (1985) observed without state intervention aid positively impact on growth. Levy (1988) foreign aid stimulates growth and enhances domestic access to modern technology, managerial skills, and foreign market. Synder (1993) developed an empirical model that incorporates country size for 69 developing countries in 3 periods 1960s, 1970s, and 1980-1987. The study found aid on growth is positive and significant. Ghulam (2005) in a Pakistan study from 1960-2002, employed regression tool, this study found aid has positive effect on the economic development. Feeny (2005) focused on Papua New Guinea from 1965-1999 adopting ARDL found that aid has positive impact on growth after SAP/World Bank reforms. McGillivray (2005) in a study between 1968 and 1999 which focused on selected African countries found that aid reduced poverty and improved growth. Lin and Tang (2017) in a gravity model revealed that U.S. and China export strengthened by their aids to African partners. Noh and Heshmati (2017) in a gravity model bilateral analysis involving ODA and export between 1996-2014, found two-way casual relationship between ODA and export effectiveness, and humanitarian aid and loan type in an effective ODA that positively impact on export. Pettersson and Johansson (2013), Chenery and Strout (1966), Nowak-Lehmann, Martinez-Zarzoso, Herzer, Klasen and Cardozo (2013) reports that aid positively impact on recipient export. Michel (2016) policy findings are therefore clear on the next global agenda for looking beyond aid to integrate LDCs on a sustainable and coherent development agenda.

7. Method of Study

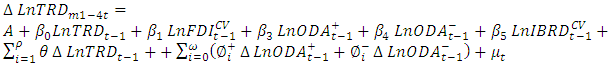

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

8. Result and Discussion

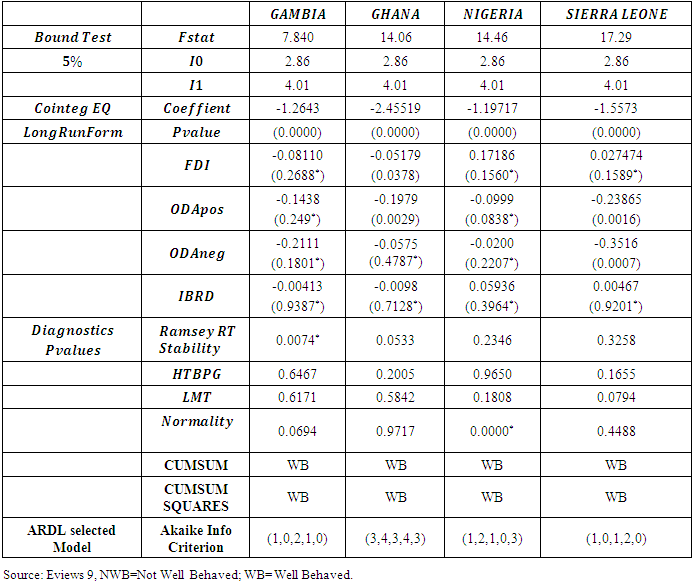

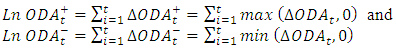

- The result presented in table 1 showed the long-run impact of ODA on trade in WAMZ within the NARDL framework from 1970-2017. The analyses is divided into four phase namely; bound F-test at 5 percent level of significance, error correction term which captures speed of cointegration, Long-run impact of increase in ODA inflow on trade and the impact of decrease in ODA inflow on trade, and the diagnostic test results. The ADF unit root test confirms that the variables are I(1).First and foremost, the trend analysis between ODA and trade is shown the graphs below.

| Figure 1-4. Trends in ODA and Trade for Gambia, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone |

|

9. Implication of the Study

- First and foremost the result violates the underlying theoretical positions put forward by Chenery and Strout (1966) two gaps and McKinnon and Shaw (1973) financial liberalization. The study is consistent with Lucas paradox of (1990). The study shows that ODA has negative impact on trade and by extension has not produced the required impact on WAMZ economies. The empirical meaning of the negative impact of ODA inflows on trade volume connote that in the long-run ODA is not effective instrument to stimulate trade in WAMZ. The negative value of ODA on trade also implies that OECD/WTO conflicts with the findings in this study. The implication of the results explains that ODA would in the long-run distort trade in WAMZ. Additionally any corresponding volatility i.e. increase (rise) or decrease (fall) would cause negative shock disturbances on WAMZ trade volume. This could also imply that because WAMZ country is import dependent economy, ODA tends to increase net trade deficit leading to the negative numbers in the results in the table above. More so, ODA as a component of AfT, the result also implies that AfT in WAMZ do not reduce trade- transaction cost associated with multilateral trade relations between WAMZ and the rest of the world. But, from the result above, FDI and loans from IBRD affect Gambia, Ghana negatively and at same manner positively affect trade size in Nigeria and Sierra Leone. FDI inflows and IBRD inflows in the system, positively impacted on trade in Nigeria and Sierra Leone, and generated a negative impact on trade in Gambia and Ghana. However, the bound test result shows that ODA has a long-run relationship with trade volume in WAMZ. This result could be significant for OECD and WTO in their policy agenda to improve the effectiveness of Aid to improve trade. Thus, ODA inflow can be used to improve trade in WAMZ. Thus, with the long-run relationship between ODA inflows and trade, foreign aid for trade (AfT) policy is effective for trade growth. With the speed of convergence in table 1, clearly, shows that ACFTA and AfT would be beneficial for WAMZ.

10. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This result does not support Papanek (1972), Levy (1988), McGillivray (2005), and Egbuna et al (2013). But it is in tandem with Adenaeur and Vagassky (1998). We could recall that AfT is directed at cost-reduction agenda associated with multilateral trade. From the result we therefore conclude that due to the negative impact of ODA inflows on trade, it shows that ODA inflow into WAMZ have not reduced cost associated with multilateral trade identified as the core problems affecting trade-growth volume and earnings accruable to WAMZ. Secondly, ACFTA might be threatened with ODA inflow which shows connection with the findings in Adenaeur and Vagassky (1998). For ODA inflow to impact on trade in WAMZ, it must be targeted at exterminating inefficiency; improve managerial and technical know-how in the processing of raw materials for trade. At same time ODA inflow should be more rural based and targeted at improving efficient utilization of available resources in order to improve the trade capacity of WAMZ. Additionally, ODA inflow should be targeted at improving the value chain and improve the potentials of WAMZ to trade in finished good rather than in primary goods. By this effort WAMZ could benefit from ACFTA, because as foreign exchange earnings from trade increases it directly increases external reserves required for convergence. Lastly, due to the fact that increase and decrease in ODA inflows impact on trade negatively, WAMZ should maintain a percentage constant flow of ODA inflow, because both inflows of ODA i.e. increase and decrease in ODA inflow has negative impact on trade volume.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML