-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2019; 9(6): 273-281

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20190906.01

Factors Affecting Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions in Algeria: Application of Shapero and Sokol Model

Grari Yamina , Benachenhou Sidi Mohammed

Faculty of Economic Sciences, Abou Bekr Belkaid University, Tlemcen, Algeria

Correspondence to: Grari Yamina , Faculty of Economic Sciences, Abou Bekr Belkaid University, Tlemcen, Algeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper proposes to explain the entrepreneurial intention of master students at the university using the Formation of Entrepreneurship Event theory (Shapero and Sokol 1982) developed by Krueger, derived from the field of entrepreneurship. According to the proponents of this theory, the entrepreneurial intention is influenced by two basic factors: Perceived Desirability and Perceived Feasibility of entrepreneurship. The field study was conducted on a sample of 165 Master students at the University of Tlemcen (Western Algeria). In order to test research hypotheses, we used Structural Equations Modeling. Our results enabled us to confirm the positive impact of desirability and feasibility on Entrepreneurial intention ion of the students. This study revealed another interesting outcome: the key role of the desire to work in predicting the Entrepreneurial intentions of Master students.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurial Intentions, Perceived Desirability, Perceived Feasibility and Structural Equation Modeling

Cite this paper: Grari Yamina , Benachenhou Sidi Mohammed , Factors Affecting Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions in Algeria: Application of Shapero and Sokol Model, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 9 No. 6, 2019, pp. 273-281. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20190906.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Entrepreneurship today is one of the most important economic and social stakes in the world [61]. At present, the consideration of Entrepreneurial thinking is the result of a wide-ranging knowledge process. Many researchers have pointed out that a decision to undertake a contract is very complicated, because it is primarily the result of precise mental processes [10]. Many of the successive intellectual currents in the field of contracting were concerned with the interpretation of the phenomenon of starting a business. These researches focused for a long time on the individual and demographic characteristics, to find the reasons that lead to the ownership of the institution or the decision to start it. According to Mahmoudi et al (2014), theoretically, the studies on entrepreneurship explained the latter through three approaches: Trait Approach, which focuses on the contractor's personal characteristics; Behavioral Approach, which examines the impact of environmental factors, Demographic and Cultural Approach which studies the behavior of the contractor [18]; Finally, there is the Interactionist approach, which focuses on the entrepreneurship intention [42]. In this regard, Tounés (2006) stressed the need to study the factors and reasons behind the emergence of Entrepreneurial intentions. According to Krueger and Carsrud (1993, p. 324), the study of the future behavior of starting a new business can not be separated from the intentions that motivate individuals to demonstrate this behavior [34]. They also stressed the need to pay attention to the study of entrepreneurial intention in individuals, which they considered to be the best indicators affecting the behavior of starting a business [58]. Several studies dealt with the subject of entrepreneurship intention through two basic models: Formation of Entrepreneurship Event [53] and Theory of Planned Behavior [1]. According to Krueger et al, (2000) these two models are strongly integrated with each other [36]. The objective of this study is to explain the entrepreneurial intentions of individuals in the academic field. Therefore, our focus will be on understanding the factors influencing the students' intentions in starting a business, focusing on the entrepreneurship model of Shapero and Sokol (1982) developed by Krueger and Carsrud (1993).

1.1. Problem Statement of the Study

- According to the studies and discussions mentioned above, and to find out the factors that affect the establishment of small and medium business by university students and encourage them to start their own project when they leave the university, all this leads us to raise the following main problem:How do the perceived desirability and feseability of entrepreneurship affect the intention of Master students to start a new business?The questions derived from the main problem are the following:1) Is there an impact to realize the students' desirability to start a new business on their entrepreneurial intention?2) How does the perceived feasibility to create a new firm by the Master students affect their entrepreneurship intention?

1.2. Purpose of the Study

- The results of the studies conducted on university students confirmed that the two models: Formation of Entrepreneurship Event by Shapero and Sokol (1982) and the Theory of Planned Behavior by Ajzen, (1991) are very good at interpreting most of the social behaviors leading to the establishment of the institution by students [13]. Currently, there is no field study in Algeria that tried to explain the behavior of the university students through applying the Shapero and Sokol model, so we aim to determine whether the model of the entrepreneurship event has a role in explaining the entrepreneurial intentions of the Master students at the university. The importance of this study is that the decision to create a firm is very complex because it is not primarily based on accurate mental processes, on this basis we will try to study the future entrepreneurial behavior of the master students by relying on the model of the entrepreneurship event of Shapero and Sokol (1982). The overall objectif of our research is to update a range of cognitive variables that contribute to the integration and interpretation of the entrepreneurial intentions of individuals in the academic field, and how these intentions can turn into real actions. In this perspective, the aim of this paper is to provide further clarifications on entrepreneurship by addressing the Shapero and Sokol (1982) model, which was developed by Krueger (1993a). According to the theory of this model, the intention to start a certain behavior is an intention to create a business in an individual is assumed by two basic factors: perceived desirability and perceived feasibility of creating a firm.In the field study, we applied a hypothetical-constructive approach based on the analysis of simultaneous correlations between the study variables to account for the relative effects of the explanatory factors (perception of desire and feasibility) of the entrepreneurial intentions of 165 Master students in different specialties at the Department of Economic Sciences at Tlemcen University. The method used in statistical analysis was the structural equation modeling model (SEM) using Software Statistica. The estimation method used was the Generalized Least Square method. The results presented are derived from both factor analyzes and multiple linear regressions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurial Intention

- According to Emin (2004), many intellectual schools in the field of entrepreneurship have followed the interpretation of entrepreneurial intention, particularly the approach of personal qualities, the demographic and environmental approach, and the pragmatic approach [21]. The studies conducted by Krueger and Carsrud (1993) adopted an interactive approach based on the fundamental role played by intention in the organizational process. In this regard, many researchers such as Davidsson (1995); Kolveried (1996); Reitan (1996); Autio et al (1997) agreed on his opinion and pursued the same ideas [21]. According to Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), intention is the best predictor of individual behavior as the first step of the entrepreneurial process [37]. In this context Ajzen (1991) considers that intention is the best indicator of voluntary behavior. This is based on the opinion saying that we can greatly predict the entrepreneurial behavior of individuals in starting a new-firm and/or exploiting opportunities by intention -oriented behavior [36]. The long study conducted by Kautonen et al, (2013) showed that entrepreneurial intention is already the best predictor of entrepreneurial action [30]. According to Battistelli et al (2003), the definition of intention is complex because it includes other terms such as purpose, spoken intention, and behavioral intention [9]. Therefore, there are no uniform definitions; some describe it as governance, others as the will, while others focus on its content. However, the point that is made between them is that the intention exists in the mind of the individual who develops it and is related to the transition to action [53, p.61]. Boutinet (1999) defines intention as the movement in which the mind tends to (missing) the inner thing [18]. This definition means that intention is the act of orientation towards the goal [53, p.61]. On this basis, entrepreneurial intention plays the role of mediator or catalyst that paves the way for starting a new-firm by the individual [23]. The intention is based on the idea that any deliberate action is preceded by the structure of a particular behavior. Therefore, the organization begins with a number of stages, beginning with the idea and then with intention and moving towards taking the actual decision of the establishment [20]. According to the results of the studies made by: Krueger and Carsrud (1993); Davidsson, (1995); Reitan (1996), Kolveired (1996); Autio et al (1997); Begley et al (1997); Tkachev and Kolveired, (2004), all voluntary behavior is preceded by the structure of the transition towards behavior, and that the intention of creation is linked to the attractiveness of this choice for the individual and his perceived feasibility of the project.The researchers in the field of entrepreneurship conclude that most of the models that dealt with the subject of entrepreneurial intention are derived from two main models: the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) of Ajzen (1991), which is rooted in social psychology and the Formation of Entrepreneurship Event (FEE) of Shapero and Sokol (1982) which belongs to the entrepreneurship field. Krueger and Brazeal (1994) and Krueger et al (2000) point out that these two models are strongly integrated [58]. Finally, we would like to point out that many theories [eg 1; 2; 8; 28; 42; 60] pointed out that individuals prefer to choose the desired and useful goals. It is not surprising to say that the founders of the theory of reasoned action [26] and the model of entrepreneurship induction [53] and the theory of planned behavior [1] unanimously agreed that desirability and feasibility are among the fundamental determinants of intention. We, therefore, choose the Formation of Entrepreneurship Event variables to construct the theoretical model for our study.

2.2. Entrepreneurship Event Model of Shapero and Sokol (1982)

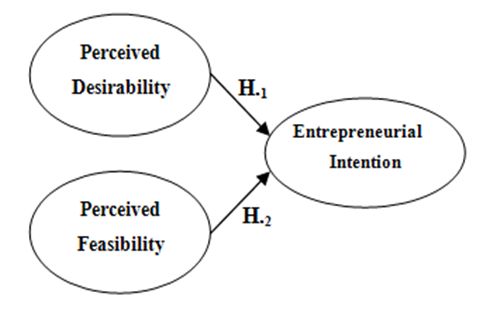

- Shapero and Sokol (1982) are among the first researchers to have an interest in interpreting the choice of entrepreneurship occupational career [29]. This model seeks to interpret the entrepreneurship event (the study of explanational elements for choosing entrepreneurship) from the practical rather than the functional path, [61]. According to Shapero and Sokol model (1982), the emergence of the entrepreneurial phenomenon is influenced by perceived desirability (The system of individual values and the social order of the individual), and perceived feasibility (Financial support; and potential partners) of the behavior of the establishment of the organization (see figure.1). According to Shapero (1982), desire is built by the influence of culture, family, peers, professional contexts (colleagues) and school (mentor). According to Shapero and Sokol (1982), positive displacements (migration, job loss, divorce … etc.) and intermediate situations (exit from the army, prison, or school) affect the value system of individuals and therefore perceptions of desirability. Shapero and Sokol (1982) noted that the founders / entrepreneurs could have suffered a shock in their private or professional life, which gave them a desire for entrepreneurial (missing). The writer adds that the desirability here can be the result of formation [51]. Feasibility consists of perceiving the factors that support the establishment along the lines of motivation to success, the availability of the necessary financial resources, the availability of human counseling and assistance (husband, friends and colleagues), and technology, such as the organizational structure, all this affects the perceived feasibility [57;58]. These perceptions are the product of the cultural and social environment and define personal choices [29]. According to Wang (2010) this model is based on the transitions term. Researchers have explained the work of entrepreneurial through three groups of elements: 1) negative displacements experienced by the individual, such as divorce, migration, expulsion from work, .., 2) intermediate situations; and it is about getting out of military service, from school, or even from prison; and 3) the third element is positive displacements; family influence, market opportunities, potential investments, etc. [61, pp. 34-35]. According to Tounés (2006) that in the interface between these three factors and construction work, the authors identified two sets of intermediate variables: perceived desirability and perceived feasibility [58]. This model points out that to encourage the emergence of entrepreneurship intention there must be a simultaneous interaction between perceived desirability and perceived feasibility. The model proposed by Shapero and Sokol (1982) did not explicitly refer to the intention to starting the firm, because Krueger and carsrud (1993), one of the strongest proponents of this model, modified it by adding it to the variable of intention [56]. Krueger and Carsrud (1993), suggest that constructors must first recognize the construction act as "credible" (meaning they have constructive intentions) and then encourage the actual launch of the project [34]. Credibility is based on perceptions of feasibility, desire and a tendency toward action that has a modified effect. If we exclude the tendency towards action, there are only two elements that explain the intention of starting the firm: the desire for action that reflects the attractiveness of the individual towards entrepreneurship, and the feasibility of the act that measures the perception of the ease or difficulty that the individual expects to face during the construction process. Of course, perceived desirability and perceived feasibility reflect the credibility of the option of starting a firm and thus are all shaped by individual experiences [61, p.35], and that displacements (positive, negative, internal or external) appear to be important precedents in entrepreneurial job [20, p.70].

3. Theoretical Model and Research Hypothesis

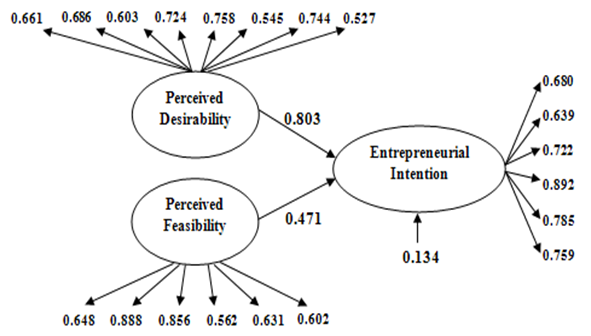

- Through this study, we followed a hypothetical-constructive approach to construct an explanatory model of entrepreneurial intention. The theoretical model of our research (see figure.1) consists of two independent variables: 1) perceived desirability (PDR); and 2) Perceived Feasibility (PFB) of entrepreneurship. They are supposed to affect the entrepreneurial intentions (EI) of the students in question.

| Figure 1. The research model |

3.1. Relationship between Perceived Desirability and Entrepreneurial Intention

- The transfer factors we discussed in the previous paragraph are considered necessary for the individual to rush to entrepreneurship [12, p.124]. Shapero and Sokol (1982) have previously pointed out that increasing the rate of the start of firm is based on cultural and social factors. In this regard, Krueger and Carsrud (1993) point out that the individual's intention to move into entrepreneurial behavior is influenced by two fundamental factors: the perceived desirability of entrepreneurship (the individual appraisal system, the social system of which the latter belongs, such as family, friends … etc.), and perceived feasibility of entrepreneurship (financial support and potential partners) [34]. According to Bagozzi (1992), the attitude toward the act does not necessarily lead to the intention to move, because it reflects little of the individual's motivation towards action. In his theory of self-regulation, he emphasized the idea that individual commitment is indeed in the strong desire of the latter to act [5;21]. This corresponds to attitudes towards the behavior and self-standards advocated by Ajzen (1991). In this regard, Emin (2004) points out that desire here becomes a direct precedence of intention, and thus plays a minor role between an individual's attitude and intention to initiate a certain behavior [21]. The author explained that this concept is very similar to Shapero's "Perceived Desirability" variable, which points out that directness in establishing a firm is a desirable behavior by an individual [21]. Based on the above and according to the theory of entrepreneurship event we propose the following hypothesis:H1: Perceived desirability to start a business has a positive impact on the entrepreneurial intention of Master students

3.2. Relationship between Perceived Feasibility and Entrepreneurial Intention

- According to Shapero and Sokol (1982), the potential originator must understand entrepreneurial work as "feasible" in the sense that it is useful [34]. The latter expresses the degree of confidence an individual has in his ability to create or acquire a firm [20, p.74]). The degree of ease or difficulty perceived by the individual also reflects a particular direction of action, as is also known as the perception of the "presence or absence of resources and opportunities" to achieve a particular behavior. In interpreting this determinant, Shapero and Sokol used the concept of feasibility of the entrepreneurship act. Bandura (1982) on the other hand used the term self-efficiency to interpret a person's confidence in his ability to do entrepreneurship work [6]. Davidson (1995), for his part, used the construct of conviction and compared it to perceived personal effectiveness and perception of behavior controls [19], while McGee et al (2009) spoke of self-efficacy [45;42]. Studies on entrepreneurial intentions have confirmed that personal competence can measure the individual's belief about his or her ability to carry out the project of establishing a firm and thus to recognize his control over his behavior. So we can suggest the following hypothesis:H2: Perceived feasibility to start a business directly affects the entrepreneurial intention of Master students

4. Methodology

4.1. Measurement

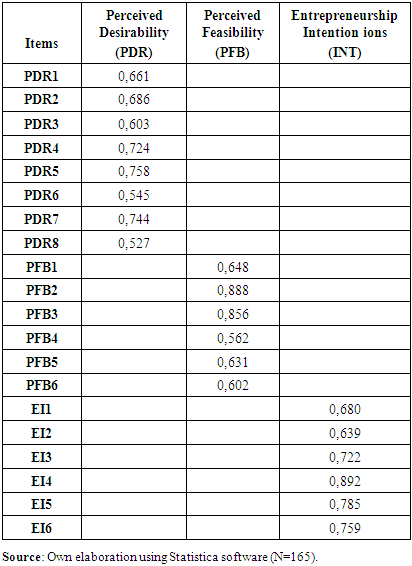

- In structural equation modeling, a distinction is made between single item variable and variables computed from multiple items. Single item variables are referred to as observed variables, while multi item variables are called latent variables [43]. In this study there were two independent variables and one dependent variable of three latent variables. The measurement of the different dependent (entrepreneurship intention ion) and independent (perceived desirability and feseability) variables of this study were adopted and revised based on the items used in the study carried out by Liñán & Chen (2009). Prior studies have used this items such as Bagheri and Pihie, (2014); Botsaris & Vamvaka, (2016); Guerrero & Urbano, (2014); Liñán et al., (2013); Liñán et al., (2011a); Liñán et al., (2011c); Matlay et al., (2012); Miralles et al., (2015); Pihie and Bagheri, (2013); Santos & Liñán, (2010); Shirokova et al., (2015); Xu et al., (2016); Zampetakis et al., (2015); Boucif, (2017, p.78).They are; Perceived Desirability (PDR); Perceived Feasibility (PFB) and Entrepreneurial Intention (EI). Eight indicator items were designed for PDR variable (PDR1, … PDR8), six indicator items for PFB variable (PFB1, …, PFB6) and six indicator items for EI variable (EI1, … EI6). All together, there are 20 items in the research instruments. We have adapted the items to the context of Master students at the University of Tlemcen (west Algeria).

4.2. Data Collection and Sample Population

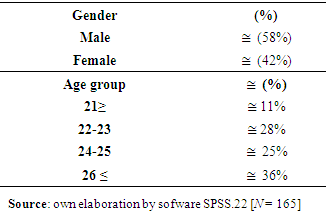

- These interviews allowed us to design the questionnaire, to use language adapted to the interviewee, and to determine the aspects that influence student’s entrepreneurship intention. We conducted a survey focusing on Master students at the Faculty of Economic Sciences at the Algeria University. The field work was lasted three months. One hundred and sixty-five usable surveys were retrieved. Table.1 shows the socio-demographic profile of the final sample. Table.1 presents the description of the respondents, including demographic data such as gender and age. Our sample comprised almost 58% male and 42% female respondents. In terms of age, nearly 11% of participants were less than 20 years, 48% between 22 and 25 years, and nearly 36% more than 26 years. One of the limitations of our study is that we did not control for some socio-demographic variables that may have an effect on entrepreneurship intention of students, such as speciality, or income.

|

4.3. Data Analysis Procedure

- We analyzed our dataset in two steps, each of which used two multivariate techniques. The reliability test of the dataset was performed using Cronbach’s alpha and principal component analysis (PCA). The reliability test was run in order to ensure consistency and reproducibility of the instrument [48;11]. For the independent variables, we performed with varimax rotation for building the constructs, using the factor loadings as new variables that summarize the items. Next, we aimed at testing the hypothesized model by using Statistica.08. The simultaneous model is expressed in Equation:EIi = β1i.PDRi + β2i.PFBi + ZetaiIn which:EIi: Entrepreneurship intention ion for student i;PDRi: Perceived Desirability for student i;PFBi: Perceived Feasibility;β1i: coefficient of desirability for student i;β2i: coefficient of Feasibility for student i;Zetai: measurement error.

5. Result

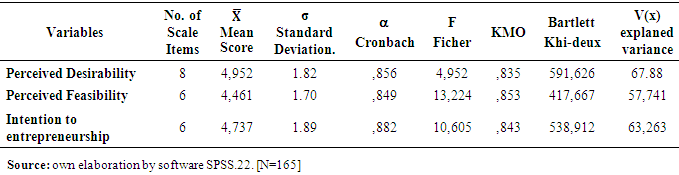

5.1. Reliability and Discriminant Validity Test

- Table 2 provides measures of reliability and discriminant validity with inter-trait correlations.

|

|

5.2. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

- To evaluate the measurement and structural model, the data were analyzed using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) with software STATISTICA.8.0. The most common SEM estimation procedure is Ordinary Leas Square estimation (OLS) and Ganeralized Least Square (GLS). This method is suitable for this study because the objective of this research is to test the causal relationship between the predictor variables entrepreneurial intention and also to investigate the extent to which predictor variables influence student’s entrepreneurial intention.The structural model was used to test the validity of the hypothesized model and further provides path analysis for the determination of how constructs relate to one another, in reality. Firstly in order to test the hypothesis, the structural model was run. The model fit was examined using absolute, parcimonious and incremental fit indices. The result of our structural model produced a better fit, because the result revealed that the data is acceptable such as Joreskog (GFI=0.861); Joreskog (AGFI=0.827); Bentler Bonett Normed Fit Index (BNFI =0.711); Bentler-Bonett Non-Normed Fit Index (BBNNFI=0.822); Bentler Comparative Fit Index (CFI=0.842); James Mulaik-Brett Parsimonious Fit Index (JMBPFI=0.719); Bollen's Rho (BR=0.789); Bollen's Delta (BD=0.843), The RMSEA = 0.075, The Chi2 global fit indices are significant (P-Level=0.000) and the ratio Ch2 /DF (2.22) is in the acceptable interval between [2-5] which indicate moderately fit the data. Secondly, the path coefficients by estimation procedure OLS for the hypothesized links (βi) were tested and it is significant with the values varying from 0.471 to 0.803. Therefore, the structural equation of our empirical model can be written as follows: EI=0,803.PDR + 0,471.PFB + 0,134. Fig.2 shows the structural and the testing results. All the indices are at acceptable levels. Overall, the results showed that our model provides a valid framework for the measurement of students’ Perception Desirability and Feasibility for entrepreneurship.

| Figure 2. The Global model and result of SEM analysis |

6. Findings and Discussion

- These two hypotheses are in line with the results of empirical studies conducted by researchers in the field of entrepreneurship [36;21], and correspond to Ajzen (1991), who said that sometimes there is sufficient positions and feasibility to influence the intention to conduct the act, it also confirms the modeling of the entrepreneurship event of Shapero and Sokol (1982). In fact, this result provides partial answers to the professionals in the field of entrepreneurship that their interest should not be confined solely to the development of skills and technical knowledge in favor of the desire to calculate the feasibility, and to focus their efforts on training and guidance programs pedagogy worse at the university or specialized centers, so they can have positive perception of the feasibility of entrepreneurship. In addition to perceived desirability and feasibility. In addition to perceived desirability and feasibility, the training programs in the field should be taken into account in addition to the contextual and personal factors that can contribute to the enhancement of the entrepreneurship abilities, which in turn affect positively the entrepreneurial intentions [57, p.374]. On this basis, in addition to perceived desirability and feasibility, intention must be paid to the training programs in the field of entrepreneurship, in order to develop the entrepreneurship skills in university students.

7. Conclusions

- The environment in which firms are active is replete with a range of economic, political, cultural, social and ecological variables that can contribute, from near or far, to facilitating or hindering entrepreneurship projects by influencing the future intentions of young people. It can also play an essential role in building the entrepreneurial intentions of university students [25]. The main conclusions we have drawn from this research is the importance of the form of the entrepreneurship event proposed by Shapero and Sokol (1982) in determining the entrepreneurial intentions of Master students at the Algerian University. In this paper we tried to test the effect of the variables of the formation of the entrepreneurship event on the intentions of the university Master students in the starting of a new business. In this regard, the results obtained in general were satisfactory.

7.1. Managerial and Perspective Implications

- In theory, the framework for this study consists of the societal dimensions of entrepreneurship model. This is the case of Shapero, Sokol (1982) entrepreneurship event model. Empirically, we tried, through our theoretical model, to ascertain the impact of social criteria on the entrepreneurial intentions of 165 Master students at the Tlemcen University (Algeria).The ability of this model to predict entrepreneurial intentions has been demonstrated by many studies such as: Krueger, (1993; 2000; 2007); Davidsson, (1995); Kolveired, (1996); Kennedy et al. (2007); Emin, (2004); Tounés, (2003 and 2006); Fayole and Gailly (2009); Fayole and DeGeorge, (2006); Boissin et al; (2007 and 2009); Ede et al., (2010); Taouab, (2014). The results shown in Table.4 show that the use of the model of intention can be useful for predicting the business's construction intention in the academic community, since more than 50% of the variation of the entrepreneurship intention has been interpreted by the latter and thus can contribute significantly to the student sentrepreneurial intention. Education, training, and awareness of the field of entrepreneurship can also contribute to increasing the entrepreneurship capacity of students who intend to set up workshops that are specifically designed to develop their entrepreneurship skills and help them in the actual start of their institutions. When university students have a desire for entrepreneurship behavior and realize that there is a feasibility of entrepreneurship, it increases their determination and strengthens their intention to starting their own business.

7.2. Limitations of the Study and Future Directions

- The characteristics of the studied sample can cause the results to be disturbed. Therefore, the selection of sample respondents must be examined so that the results obtained can represent the society from which they were taken. As well as the paragraphs of the questionnaire can also be a barrier to understanding the purpose of the research, so the paragraphs should be formulated very carefully to be uncomplicated and easy to understand and correspond to the social structure of the sample studied.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML