-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2019; 9(4): 199-206

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20190904.05

Determinants of Bank Savings Mobilizations in Nigeria. The Engel and Granger Approach

Ikubor Ofili Jude

Department of Economics, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ikubor Ofili Jude, Department of Economics, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study examined the factors determinants of domestic savings in Nigeria from the period of 1981-2017 using Engel and Granger approach to co-integration and parsimonious ECM analysis technique to test for the existence of relationship between the variables of this study and causal impacts. The result found that interest rate exerts negative impact on domestic savings which co-exist with positive impact of foreign exchange rate, investment rate and per capita income on domestic savings in the short-run. There is a long run feed-back from the determinants in the long run the error correction term. We therefore recommend, among others the need for government in Nigeria to direct their policy towards improving the lending and savings rates and increase per capita income level of the populace, thus stimulate savings for investment and economic growth.

Keywords: Savings, Interest Rate, Mobilizations, Government, Inflation

Cite this paper: Ikubor Ofili Jude, Determinants of Bank Savings Mobilizations in Nigeria. The Engel and Granger Approach, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 9 No. 4, 2019, pp. 199-206. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20190904.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- There is the need to put in place a coherent economic policy that will encourage domestic savings in Nigeria. Thereby, placing the right savings culture by institutions and regulatory agency who influence the decisions of households, firms and government. Savings in developing countries are expected to play very vital and effective roles in financing economic projects and activities as its contribution in ensuring sustainable economic growth. This expectation is as a result of the fact that there is acute shortage of capital in the developing countries of the world.According to Shaw (1973) financial or credit development can foster economic growth by raising savings, improving efficiency of loanable funds and promoting capital accumulation. It is the availability of the bank credit through savings, that allows firm to increase production, output and efficiency and in turn increases the profitability of the banks through interest earned and return on investment. Fundamentally, economic system is been driven by savings because of its importance in the financing of commerce and industry and in helping to stimulate economic viability, ensuring growth and development. Domestic savings is a vital importance in the sustenance and reinforcement of the saving- investment growth chain in developing economies Nwachukwu, and Odigie, 2011). Any economic system that save more tend to grow faster, provided that their financial system is deep (World Bank, 1989).The intermediation process involves moving funds from surplus economic units of the economy to deficit economic units (Uremadu, 2002; Nnanna et al 2004) Financial intermediation plays an important role in the economy because it allows funds to be channeled from people who might otherwise not put to productive use to people who will. In this way, financial intermediation helps to promote a more efficient and dynamic economy. However, the extent to which this could be done depends on the level of development of the financial sector as well as the saving habit of the populace. The availability of investible funds is therefore regarded as a necessary start point for all investment in the economy which will eventually translate to economic growth and development (Uremadu, 2006).Access to financial service is important for important for growth and poverty reduction. Access to credit that enables an individual to accumulate funds in a secure place over time can strengthen productive assets by enabling investment in micro-enterprises, in new tools, equipment or fertilizer or in education or health, all of which can play an important role in improving their productivity and income. However, in many developing countries like Nigeria, commercial banks lending or access to formal financial services for the poor majority of the population remains very limited. Credit is the main channel through which savings are transformed into investments. However, not all savings are used to finance investment despite high demand for credit because the credit market in Nigeria is rationed (Soludo, 1987; Azege, 2007). Indeed, the lack of credit has been cited by firm Managers in Africa as their most important constraint (Bigstein et al. 2003).Lack of funds has made it difficult for firms to invest in modern machines and human resources development which are critical in reducing production costs, raising productivity and improving competitiveness. Low investment have been traced largely to banks unwillingness to make credits available to manufacturers, owing partly to the mis-match between the short-term nature of banks funds and the medium to long term nature of funds needed by industries. In addition banks perceive manufacturing as a high risk venture in the Nigeria environment, hence they prefer to lend to low –risk ventures, such as commerce, in which the returns are also very high. Even when credit is available, high lending rate, which was over thirty percent (30%) at a time, made it unattractive, more so when returns on investments in the sub-sector have been below ten percent (10%) on the average (Nwasilike 2006).Entrepreneurs have accused banks of enjoying abnormal profits by charging high rates on credits whilst paying considerably lower rates on deposits. Bankers on their own part have argued that the perceived high spread is necessitated by the high costs of running banking business arising from regulating costs as well as those induced by the environment where they operate such as costs of power and infrastructural decays, etc (Afolabi et al, 2003).Inspite of the fact that Nigeria has implemented some economic policies that are based on financial liberalization as elucidated in the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) and other banking reforms, the issue of the persistent low level of economic development in Nigeria still remains a matter of great concern. To this end, it becomes imperative to carry out an empirical investigation on the performance of the banking sector as a financial intermediary. The research question that comes to mind is what are the determinants of bank savings in Nigeria, because there is there is acute shortage of capital in the developing countries of the world such as Nigeria. It would be recalled that the banking crisis in Nigeria in the 1980’s was associated with major macroeconomic disruptions such as sharp increase in interest rate on lending, large currency depression and devaluation, lasting decline in the saving culture in the financial industry. In Nigeria, there is lasting need of further efforts especially in mobilizing small savings in both urban and rural areas, and the process of financial intermediation itself, knowing fully well the saving culture in Nigeria is very poor relative to other developing economies (Uremadu, 2002).In fact, the performance of saving mobilization in Nigeria has not been encouraging. Instead of increasing to match the development challenges, there is a clear indication of saving decline in Nigeria, inspite of various policy measures. These measures include rural banking program, establishment and bank recapitalization expansion of People’s Bank of Nigeria, Primary Mortgage Institutions, Insurance Companies and the Social Insurance Trust Fund which was reconstituted from the National Provident Fund. In fact, the National Bureau of statistics (NBS) estimated Nigeria’s Gross National Saving in 1993 to be #63.4 billion rising from #59 billion in 1991, and declined again to #59 billion in 1996. (Orji, 2006). Therefore, the main objective of this study is to identify the determinants of banks savings in Nigeria while the specific objectives are to identify the factors that has the strongest impact on bank savings in Nigeria and to examine the trends of bank savings in Nigeria. The rest of the paper is divided into the following sections. Section 2 is the literature review, section 3 is the research method, section 4 is discussion of empirical results and section 5 is summary, conclusion and policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

- Savings may be defined as after tax income not spent. It may rightly be referred to or presumed “deferred consumption’ being income left over for future consumption on capital investment or for precautionary and speculative motives. Concisely, savings is summed as disposable income less consumption. In developing countries and Nigeria in particular, domestic savings constitutes the main source of capital accumulation for investment purposes.From theoretical literatures, total savings of households, entrepreneurs and corporate entities in an economy has positive correlation with output. Amongst other things, savings serve as the main source of financing investment and related economic activities. According to Krieckhaus (2002) a higher level of national savings leads to higher investment and consequently higher output. This is so because the level of savings determines the magnitude of capital accumulation. On the other hand, the magnitude of total earnings depends on the level of total output. Thus output also determines the level of savings (capital accumulation) and investment by households and entrepreneurs. This means that a change in the level of savings will systematically cause a change in capital accumulation (capital stock) and consequently a change in output. Output is the total value of all goods and services produced in a country at a given period of time.According to Olusoji (2003) savings represent that part of income not spent on current consumption. When applied to capital investment, savings increase output. Institutions in the financial sector like deposit money banks (DMBS) or commercial banks mobilize savings deposits on which they pay certain interest. To effectively mobilize savings in an economy the deposit rate must be relatively high and inflation rate stabilized to ensure a high positive real interest rate, which motivates investors to save from their disposable income. The recent consolidation initiative which has reduced the number of banks from eight-nine (89) to twenty-four (24) is a step towards building market-based direction. It aims at reducing the cost of capital by allowing domestic economic units to achieve efficient portfolio diversification in order to increase the liquidity of investments; and opening the financial industry to foreign investors. Ultimately, the reform initiative is meant to produce a sound and healthy financial services sector, which is crucial if the country must avail itself of the windows of opportunity opened up by globalization, to develop the economy and further the country’s industrialization.Prior to 1936, the classical economists propounded theories on the savings and asserted that a positive relationship existed between savings and interest rate. Keynes (1936) defined savings as the excess of income over expenditure on consumption. This means that saving is that part of disposable income of the period which has not passed into consumption (Umoh, 2003; Uremadu, 2006). Given that income is equal to the value of current output; and that current investment (i.e. Gross Capital Formation) is equal to the value of that part of current output which is not consumed, savings is equal to the excess of income over consumption. Keynes maintains that on the aggregate, the excess of income over consumption (otherwise called savings) cannot differ from addition to capital (i.e. Gross fixed capital formation or gross domestic investment). Savings is therefore a mere residual, and the decision to consume and the decision to invest between them determine the volume of national income accumulated in a period. In the Keynesian view therefore, rising income would result in higher savings rates. As a matter of fact, savings is regarded as being complementary to the consumption function. In the simplest form, the savings function is derived from the linear consumption function when the autonomous consumption expenditure is separated off (Umoh, 2003).In a similar note, Anyanwu and Oaikhenan (1995) classified the determinants of savings into objective and subjective factors respectively. The objective factors are the quantifiable and verifiable determinants of savings. These include; the level of income, the rate of interest, inflation rate, expectation about inflation rate, and saving facilities. On the other hand, the subjective determinants of savings are the non –quantifiable and non- traceable factors that influence savings behaviors and which are largely psychological in nature. These include; the instinct for precaution, the desire for bequest, habits and cultural factors.Nurkse (1953) and Myint (1967) among others have argued that in low income countries, there is a vicious cycle of low income leading to low savings, low investment and back to low income. Failure to break the vicious cycle by raising the saving proportion of income results in perpetual stagnation and poverty. In any development pattern for a country to develop, it must exert a major effort to improve its saving ratio. Indeed, differences in saving rates are a clear distinguishing factor between thriving economics and stagnant ones. The life –cycle theory developed Modigliani and Brumberg (1954) attempt to understand the concept of saving, based on the observation that individuals make consumption decisions based on the resources available on them over their time and their current stage in life. The theory predicts that the age composition of a country’s population should influence its savings behavior in such a manner that the higher the proportion of a country’s population that is not in the active labour force, the lower its savings rate should be. In other words, individual will dissave when they are young and have low income, save during their productive years, and once again dissave when they retire. The bequest theory by Yaari (1965) stipulates that if individuals have positive – bequest motives, they will tend to save some wealth for their heirs. Thus, aggregate savings are influenced by the demographics of the population. The theory of optimal saving stipulates that individuals should save early to create a buffer stock to cushion bad income draws and limit the negative internality from habit formation. Fisher (1930), who stated that income uncertainty increases current saving.The traditional economic theory of savings developed by Simon (1959) posits that people act as if they make en-ante optimal savings decisions under uncertainty, discounting future utilities exponentially, given their beliefs about future income and other structural parameters.The Ricardian equivalence hypothesis assumes that saving behavior does not experience any uncertainty and that capital markets are perfect. The theory posits that government can finance its expenditure through taxes or borrowing, hence the only thing that affects the economy is the time path of government expenditure and not the taxes that finance such expenditure (Ricardo 1817).The dynamically inconsistent preferences theory of Brown, Camerer and Chua (2006) stipulates that consumers know how to save optimally, but cannot resist short –term temptations to consume some products. Recent empirical evidence in Nigeria point to a growing informal financial system (Oduh, Eboh, Ichoku, & Ujah, O. (2008). This can seriously hamper the savings mobilization efforts of deposit money banks and other financial institutions in Nigeria due to the fact that most informal sector transactions are conducted in cash to avoid official detection and interest rate are very low, compared to the formal financial sector. Nwachukwu and Odigie (2011) examined the determinants of domestic saving in Nigeria during the period 1970-2007 using the ECM procedure. The result of the analysis show that the saving rate rises with both the growth rate of disposable income and the real interest rate of the bank deposits, while public saving seems not to crowd out domestic saving, suggesting that government policies aimed at improving the fiscal balances have the potential of bringing about a substantial increase in the national saving rate. Also, the degree of financial depth has a negative but insignificant impact on saving behavior in Nigeria.Akpan, Udoh and Aya (2011) used two stage least squares method of simultaneous equation modeling to examine the factors that determine household saving of rural agro-based firm workers in the south-south region of Nigeria. The result indicates that income, tax, job experience, education, family size and membership of a social group influence saving attitude of workers.Babatunde, Fakayode, Olorunsanya and Gentry (2007) examined the determinant of saving among co-operative farmers in Ondo State, South Western Nigeria. They obtained data from 150 co-operative farmers using structured questionnaires. The results of their study indicate that household size, years of co –operative membership, interest rate on loan, gender and the amount of money borrowed are the significant determinants of savings among the co-operative farmers.Nwachukwu and Egwaikhide (2007) examined the determinants of private saving in Nigeria by comparing the estimation results of the ECM model with those of partial –adjustment, growth rate and static models. They found that real interest rate on bank deposits has a significant negative impact on private saving. They also found that savings rate rises with the level of disposable income and that the ECM performed better than the other models.Osei (2011) examined the functional relationships between financial savings and macroeconomic variables in Ghana using trend analysis and ECM methodology. The study found that level of investment, deposit rate and level of income have significant positive impact on savings.Igbatayo and Agbada (2012) investigated the relationship between inflation, savings and output in Nigeria, employing Vector Auto regression Approach (VAR). The results indicate that inflation trends to reduce output while savings actually stimulates output in Nigeria.Temidayo and Taiwo (2011) employed descriptive statistics in carrying out a qualitative analysis of the relationship between domestic savings and economic growth in Nigeria, using annual secondary data obtained from World Data Indicator (WDI) for the period of 1970 to 2006. The study concluded that the problem with Nigeria’s economy is not that of mobilization domestic savings but that of intermediation and thus recommended that government should adopt policy enhancing intermediation between savings and investment in the economy by providing regulating and coordinating role to ensue effective intermediation between savings and growth in the economy.Eregha and Irughe (2009) examined the impact of foreign aid inflow on domestic savings in Nigeria using an OLS methodology. The results indicate that both the short-run and steady state foreign and inflow to Nigeria have positive effect on domestic savings. Ogwumike and Ofoegbu (2012) using an ARDL estimation technique to examine the impact of financial liberalization on Nigeria’s domestic savings 1970 – 2009. The study concluded that interest on deposit induced by liberalization was not the major determinant of saving.A number of recent studies have shown that commercial banks seem to improve banking system efficiency and thereby contribute to overall banking stability in developing countries. However, the impact of bank savings in developing countries especially in Nigeria remains largely unexplored.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Theoretical Framework

- Optimal saving decisions are embedded in a dynamic general equilibrium framework of analysis. However, the parameters of individual saving problems are jointly determined by aggregate savings and investment outcomes and ultimately by the character of income distribution at the aggregate level. The analysis is within the framework of the standard life cycle permanent income model, but it emphasizes different features of behavior to generate results far from the standard “consumption equals permanent income” story that has so far dominated empirical work in developing countries.

3.2. Model Specification

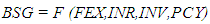

- The model takes the form: Private Domestic Saving as a function of Gross Domestic Product, Real Interest Rate, Broad Money Supply and Inflation rate.

| (3.0) |

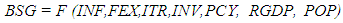

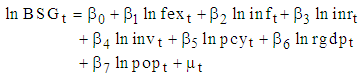

| (3.1) |

| (3.2) |

= error term

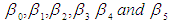

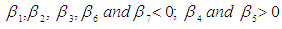

= error term are parameters to be estimated in over parameterized model.The a priori expectations are stated as follows:

are parameters to be estimated in over parameterized model.The a priori expectations are stated as follows:  Functional Form of Parsimonious Model

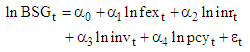

Functional Form of Parsimonious Model | (3.3) |

| (3.4) |

are parameters to be estimated in parsimonious model.

are parameters to be estimated in parsimonious model. = error termThe a priori expectation is still in line with the specification over parameterized model.

= error termThe a priori expectation is still in line with the specification over parameterized model.3.3. Method of Analysis

- The model for this study was carefully chosen to capture all the objectives of the study. The major characteristics of an econometric analysis are incorporated in the model specification in a systematic manner.This study employed Ordinary Least Square to estimate the specified model. The analysis of the data begins with the unit root test of variables since most times series data are prone to be non stationary. This is to enable us ascertain the time series properties of the variable in the model. Generally, Philips Perron unit root test will be conducted to ascertain the variables are stationary in levels or whether they are stationary in integrated order of p. i.e. I(1, 2, …, p). The variables were subjected to unit root test with constant and trend. Johansen’s co-integration technique was adapted to test whether there exist long-run equilibrium relationship between the dependent and independent variables. Also, Error Correction Model (ECM) was estimated to determine the short-run dynamics of the model and to determine the speed of adjustment.

3.4. Sources of Data

- The nature of data for this study is quantitative time series data. Data are sourced from secondary sources, such as Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) statistical bulletin and annual reports, and the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Unit Root Tests Results

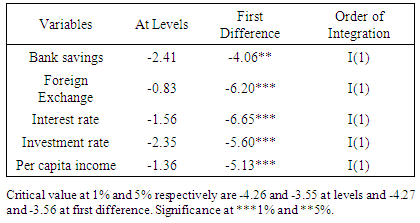

- To test the stationary properties of the data, PP (Phillips Perron) unit root tests are employed. The results for both the level and differenced variables are presented in Table 4.1 below:

|

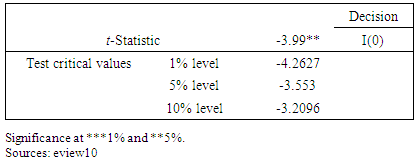

4.2. Residual Approach to Co –integration Test

- Once the order of integration of the series are confirmed I(I), we estimate the long-run relationships, i.e., run regression on equation (3.4) and save the regression residuals. In order for the determinant of saving and savings to be cointegrated, the estimated residual from the equation (3.4) should be stationary (i.e., μt ~ 1(0)). The residual-based unit root test is used to examine whether the residuals from equation (3.4) are stationary. If they are stationary, then the series are cointegrated. If the residuals are not stationary, there is no cointegration. Rejecting the null hypothesis of a unit root, therefore, is evidence in favour of cointegration (Engle and Granger, 1987). Residual-based test is estimated as follows: Δμt = α1μt-1 + εt. The unit root test of the residual used Phillips-Perron. The result of the test is as shown in table 4.2 below.

|

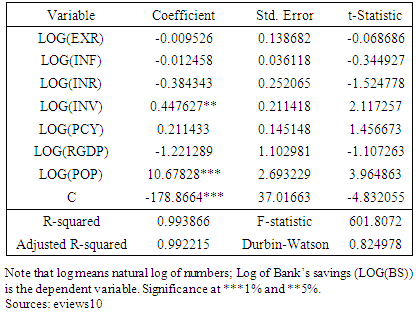

4.3. Ordinary Least Square Regression Result Interpretation (Long Run Relationship)

- Recalling equation 3.2 and 3.4 in section three, their results are presented thus.

|

|

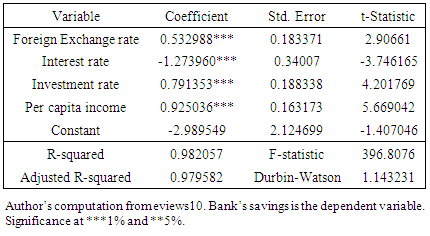

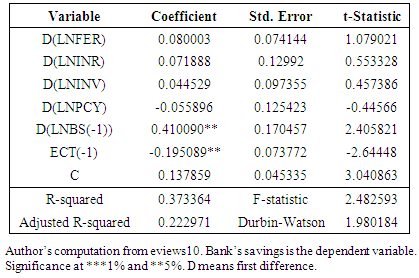

4.4. Error Correction Model (ECM)

- The significance of the ECM in the model is to indicate how disequilibrium in the dependent variable can be adjusted in the short- run through the speed adjustment mechanism of error term. The over-parameterized ECM was firstly estimated (see appendix) before the parsimonious model was estimated through elimination methods of variable.

|

5. Summary of Finding and Policy Implication

5.1. Summary of Findings

- In the previous sections, we sought to examine the determinants of bank savings in Nigeria. Our results showed that the model is subject to an equilibrating relationship and some of the exogenous variables are directly related to dependent variable while others are inversely related to dependent variable in the long run.Also, the coefficient of determination R2 was found high which showed that explanatory variable were able to account for the total variation of the dependent variable. The value of Durbin-Watson statistic (DW) shows that there was no presence of autocorrelation.The empirical result of the model in parsimonious estimation showed that all variables were statistically significant, such variables include foreign exchange, investment rate, interest rate and per capital income, while inflation rate was discovered to be irrelevant to exert effect on banks’ savings. Since income was able to cushion the effect it has on the dependent variable.

5.2. Recommendations

- The recommendations are as follows -1. Government’s effort should be geared towards further improving per capita income in order to eliminate the effect of inflation rate in the country in a bid to accelerate growth through enhanced banks savings.2. On the macroeconomic perspective, attempts must be made to achieve and maintain macroeconomic stability. This should involve efforts to stabilize the exchange rate so as to encourage the competitiveness of Nigeria exports, which increase the volume of foreign currency inflows. This would at the long run beef up bank savings in Nigeria. 3. There is need for government to constantly pursue financial sector development thus encouraging increase in the size of savings. When the size of savings is increased, enough bank loans will be available for both the private and public sector which will enhance economic growth. To this end, therefore, there is need to develop our financial intermediaries towards greater effectiveness and efficiency.4. A sound financial system instills confidence among savers such that resources are effectively mobilized to increase productivity in the economy.5. There should be a serious effort by the monetary authorities to bridge the widening gap existing between lending rate and saving rate, so that the people will be fully motivated to save more in a bid to generate the needed loan for investment in Nigeria.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML