-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2019; 9(3): 93-105

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20190903.02

Youth Unemployment Mitigation Labs - An Empathetic Approach for Complex Socio-Economic Problem

Mohamed Buheji

International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain

Correspondence to: Mohamed Buheji, International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Today many graduating youths would believe that the world is much harsher than what they thought, because they are constrained from smoothly entering the labour market. Therefore, youth unemployment is not only a United Nation Sustainable Development Goal (UN-SDG), but remains to be an important complex global challenge. In this paper, we shall review all the past and contemporary approaches to solving the youth unemployment problem, in relevance to latest facts and then shall see the approach of a four years’ socio-economic problem-solving approach, called the inspiration labs, and how it is tackling this issue from different perspectives. The paper concludes with calibration of the direction this UN-SDG challenge is handled all over the world.

Keywords: Youth Unemployment, Sustainable Development Goal (SDG), Youth Empowerment, Socio-economy, Problem Solving, Inspiration Labs, Inspiration Economy

Cite this paper: Mohamed Buheji, Youth Unemployment Mitigation Labs - An Empathetic Approach for Complex Socio-Economic Problem, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 9 No. 3, 2019, pp. 93-105. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20190903.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Youth unemployment would continue to be a complicated problem as the world is still continuing its demographic shifts in developing countries. The problem of youth unemployment will continue to carry numerous domestic and global risks, including social exclusion, mass migration and generational gaps. Buheji (2018d).At a time when young people in certain societies are being prepared as the engine of society and its sustainable resource. Youth unemployment needs an economic, social and psychological approach more than a political approach. It is a security problem that carries with deep consequences towards poverty, deprivation and frustrations which have profound effects on the level of quality of life of the community. Unemployment effects both the psychological and the physical status of youth more than ever today. Studies show that the effects of unemployment stem from a sense of failure and loss of self-esteem, which raises the rate of silence that may lead some to commit a crime, drug abuse and even suicide. In this paper, we shall explore the meaning of unemployment for youth specifically, besides modern unemployment statistics. Youth unemployment as a problem to be solved is discussed from different perspectives such as the current and required such as education and recreation activities. Economic Discussion (2019).Policies to reduce youth unemployment and the required policy reforms. Then a review for those youth not in education, not in employment and not in training, called for short (NEET). Then a review about the role of knowledge-based economy on the issue of youth unemployment is followed. Examples of youth unemployment challenges and the probability of youth staying unemployed shed light on the depth and the complexity of the problem. Buheji (2018e).Then a case study of the way inspiration labs is tackling the youth unemployment a socio-economic problem and from different perspectives is explored. A comparative discussion on the contemporary efforts in tackling the youth unemployment issue in relevance to inspiration is evaluated and discussed, then recommendations for the way forward to close this major UN-SDG gap are suggested in conclusion. Amadeo (2018).

2. Literature Review

2.1. What is Youth Unemployment?

- Unemployment can be defined as when an individual is hunting for employment and does not find a job or alternatives to a job, i.e. being self-employed. Unemployment is one of the major crisis that happens around the world every era. Therefore, it is an issue that reflects the national or international economic status and the healthiness of investment potentials. Johansson and Handelshögskolan (2015).The unemployment rate is measured by calculating the total unemployed individuals divided by the total number of the labour force in the country. As per the International Labour Organization (ILO, 2012), there are more than 200 million globally or about 6% of the complete world workforce is unemployed. For youth, their unemployment differs even more if their NEET is high. I.e. When youth are not in education and not work means we have a society a major wastage of both youth energy and spirit, Buheji (2018d).

2.2. Youth Unemployment Statistics

2.2.1. Statistics of Youth Unemployment in Modern History

- The global unemployment rate reached a post during World War II to a high of 9.7% in 1982. With the economic recession, the unemployment rate reached 9.6% in the year 1983. It was in 1989 that the unemployment rate dropped to 5% but started enhancing again. This led to 6.8% in 1991 and 7.5% in 1992. Later and with the economic development, the unemployment rate fell to 6.9% in 1993, 4.5% in 1998 and to 4% in 2000; consequently. It was considered to be the lowest in the last three decades.Since youth are essential to any economic development and growth, the drop down in the overall global unemployment rate gave great hope for the ease of young people entry to the labour market, especially in emerging and developing market economies. This is especially true as the world reach approximately one-third of its working-age being youth. Buheji (2018d), Lagard and Bludorn (2019).However, the reality today is the opposite. Still today youth, all over the world, face tough labour markets and job shortages. Approximately, 20% of 15- to 24-year-olds in the average emerging market and the developing economy are neither in work, nor in school (i.e. NEET); in comparison to 10% in advanced economies. Table (1) illustrates the percentage of youth unemployment selected developed and emerging economy countries, as per ILO (2015) statistics.

|

2.2.2. Future Foresight of Youth Unemployment

- Predictions say that youth unemployment will continue to rise in the following years. High unemployment has negative consequences on the economy of the country and population. More young people are expected to leave their countries of birth to find employment abroad.The new IMF staff study shows that, if youth underemployment in the typical emerging market and developing economy were brought in line with the average advanced economy, the working-age employment rate would rise by three percentage points and economic output would get a 5% boost. IMF (2019) and Lagard and Bludorn (2019).

2.3. Youth Unemployment - Problems Solving

2.3.1. Youth Unemployment as a Problem

- Unemployment as a problem can be solved in many ways and alternatives. Solving youth unemployment as a socio-economic problem can help to reduce the current total approaches of youth empowerment, Amadeo (2018). Most current approaches work to solve long-term youth unemployment is through ensuring better educational standards, launching of new empowerment programs, encouraging self-employment, entrepreneurship, ensuring access to basic education and reduction of the age of retirement. Buheji (2018a), Buheji (2018e).Recently, most of the scientists see unemployment as an issue that could be solved when youth become creative, positive and competitive. This led to many initiatives that target to avoiding investing in unsuitable programs. Buheji (2018d).Youth unemployment is another issue which is still happening in developed, underdeveloped and developing countries. There is major evidence that even the developed countries are battling with youth unemployment issues. The international labour organisation has mentioned the statistics of both employed and unemployed in 2012 which states that is about 6% of the world population are unemployed and youths are the ones who are unemployed, i.e. youth unemployment (ILO, 2012).Many studies now show clear evidence that the delay in youth unemployment increases their likelihood of being unemployed in their later adult life (Gregg, 2001; Bell and Blanchflower, 2009). As a result, youth unemployment will also have a sustained impact on the level of wealth and growth in future periods. Now officially EU sees youth unemployment to be a serious problem even in Europe where the Eurostat (2015) shows the unemployed youth to be 22.1%, compared to 8.9% for the adult population. This figure shows the considerable difficulties that young people are facing when trying to access the labour market for the first time.

2.3.2. Education and Unemployment Problem

- Education creates opportunities for young people that contribute to the fulfilment of their desires and the building of their personalities and the establishment of a secure and stable life. Education supposed to facilitate a better search for suitable jobs and opens the youth mindset to see opportunities in different ways. Therefore, many believe with their education certificates they would get open doors of opportunities. Buheji, (2017c), WEF (2019).The government should change the policies of requiring an expensive bachelor’s degree, that take four to five years of one’s life without real guaranteed employment outcome. Students should have more options to go to vocational school, or get a combination of liberal arts and then on-the-job training. Hence, it would be great to see companies start adopting apprenticeship programs, teaching young professionals what they need to know on the job. Ahn et al. (2019), Buheji (2018b), Buheji (2017a).Boosting on human capital education and training are no longer an effective strategy to create employable youth, or labour productivity, nor does keeping high demand for the creation of new jobs. Reddy (2017). Part of the EU recent initiatives also is to improve educational attainment so that people can work in jobs requiring higher-level knowledge and skills. EU and national policies aimed at reducing school drop-out rates. WEF (2019).The Active Labour Market Policy (ALMP) target to support youth employment and ‘youth guarantee’ schemes to ensure young people receive a job offer or continued education within a fixed period after leaving education, or becoming unemployed (European Commission 2014). This is supported with extended guidance to employment services created specifically to youth. This is also linked now to employers’ social contributions (O’Higgins, 2010; Eurofound, 2011).Now many students graduate with education fees debts on their shoulder. Lack of diversified educational models that address the different youth vs market demands needs to lead to stay in confusion in the search for work and waiting for more than ten years without suitable or permanent work. The constraints for specialization increases the complexity of the problem of unemployment.Despite their differentiated access to education, studies show that youth still suffer from inequality for jobs related to their welfare. Total unemployment could be valued at market prices, for example using young people’s wage levels and average working hours, to provide a measure of wealth lost to the EU economy, because of youth underemployment in the same present period. For example, a recent Eurofound study has shown the estimated cost of young people who are not in employment, education or training (NEETs) in 26 of EU member states to be about €156 billion (representing 1.51% of EU’s GDP) (Eurofound, 2012). To reducing youth occupational immobility, many countries started apprenticeship schemes that aim to provide the unemployed youth with the suitable skills they need to find suitable employment and to make them attractive for a suitable job. For example, in 2013, over 500,000 people started apprenticeships in the UK.Consistent with the increase in education is the decrease in the share of 16-21 year-olds in fulltime work (Barham, et al., 2009). Further, the evidence-base on particular transitions examines the impact of the constant growth of young people in temporary employment across the EU. This increased to about 42% of young people across the EU in 2010, compared to about 11% of those aged 25–59 (Eurofound, 2014). The recent (EU Commission, 2014) report shows the increased focus on improving the skills of young people to meet employers’ demands better and to reduce the mismatch between available vacancies and job seekers by supporting vocational learning in apprenticeships, traineeships and placements and introducing quality standards for vocational education. Thus funding more apprenticeships and workplace learning are now a top priority for EU countries (EMCO, 2011; ILO, 2011; O’Higgins, 2010; European Employment Observatory, 2010).

2.3.3. Youth Sport and Unemployment Problem

- Today youth-focused sports contribute to absorbing the burdens of disturbance resulting from unemployment disruption. By integrating youth into a social and cultural atmosphere, while contributing to the building of youth's personality and spirituality we can transform the energy into balanced and productive work, thus preventing deviation and mental illness.Through Improving the situation of many millions of young Europeans failing to find gainful employment, and more generally suffering from deprivation and social exclusion, has to be a priority for policy-makers’ initiatives.

2.3.4. Influence of Youth Unemployment Problem

- The problem of youth unemployment can influence the stability of national insurance contributions to society. The level of financial support expenditure for apprenticeships and internships would be influenced too. Employed youth can reduce occupational mobility and thus knowledge capital leakage. Also, a well-established employment program would help to improve geographical mobility and thus to cause improvement for the minimum wages. Once youth are employed the community would avoid the risk of the poverty trap. In 2012, 42.1% of young people across the EU were on a temporary contract which was four times the rate for adult workers (Eurofound, 2013). This shows the gap that youth unemployment does. Now it is an accepted trend and fact that full-employment does not mean zero unemployment! There will always be some frictional youth unemployment which may be useful to have a small surplus pool of labour available. Most economists argue that there will always be some frictional unemployment of perhaps 2-3% of the labour force. Amadeo (2015) seen that economic growth rate of 2-3 per cent can create only a maximum of 150,000 jobs which is not enough to prevent high youth unemployment, especially with the high influx of graduates. When unemployment creeps above 6-7 % and stays there, it means the economy can't create enough new youth jobs also.

2.4. Policies to Reduce Youth Unemployment

2.4.1. General Policies to Reduce Youth Unemployment

- Many policies are usually released to reduce youth unemployment. For example, the low-interest rates and improving credit supply to businesses, besides depreciation in the exchange rate to help exporters is part of the story. Other indirect youth unemployment policies were the infrastructure investment projects, reductions in corporation tax (to increase investment), spending more incentives for research and innovation that would encourage new business start-ups. Most countries in the world have moved their policy to rapidly support small and medium enterprises (SME’s) because of their inability to create new jobs. New policies now focus on SMEs approaches that target to transform the educated youth to be a major source of innovation and economic empowerment. Other policies, as the productive families’ empowerment policy, helped to create the right conditions for youth to start their jobs as part of the family. Such policies help youth to create the right source of income and training to enter the labour market through self-employment projects. Buheji (2018a).Recent EU reform policies and programmes (Eurofound 2012, Berlingieri et al. 2014, O’Reilly et al. 2015) aim to review the employment protection legislation in relevance to minimum wages to encourage companies to take on more young people. (Eurofound, 2011; O’Higgins, 2010).

2.4.2. Policies that Encourage Self-employment

- Johansson and Handelshögskolan (2015) studied why some youth become self-employed instead of wage or salary earners upon returning to employment, using Finnish microdata and a multinomial logit model.To close the unemployment gap, the European Union established a SALTO-YOUTH program which is a network of six resource centres working on European priority areas within the youth field. Hence, self-employment policies have shifted the focus of the government towards subsidising the cost of the new start-ups. European Union (2019). As the dependency ratio is increasing in almost all the developed countries and leading developing countries, government policies need to re-evaluate its expenditures on social security or social insurance program and focus on empowering or developing youth for creating more their markets or meeting the demands of the dynamics of the market. Young people are highly needed today to enter the labour market as self-employed, as early as possible, as they can help in managing to pay for the huge numbers of those retiring. Buheji (2018a).Evans and Leighton (1989) report that the salary youth that has entered self-employment on average have more experience than those not entering self-employment. Studies indicate that in the U.S. youth that suffers from longer duration of unemployment were more likely to enter self-employment. The more we have concrete self-employed projects that would help to reduce youth unemployment this would influence the functioning of the labour market and would enhance the investment of youth in education and development (European Commission 2014a and 2014b) and Johansson and Handelshögskolan (2015).

2.5. Key Barriers to Lowering Unemployment

- There are many key barriers to lowering the unemployment issue. For example, high levels of long-term youth structural unemployment in the UK was found to be due to the complex welfare benefits, or low paid jobs that keep families in relative poverty. WEF (2019).Studies show that one of the barriers of unemployment is that they are being stuck on part-time jobs. Other barrier found to be due to the continuous gap and variations in education outcomes or having low levels of educational achievements. Ahn et al. (2019).Other barriers to reducing unemployment are the inequality for young women who usually influenced by negative economic conditions more than young men. Parental education was found to affect young people’s employment transitions significantly.

2.6. Youth not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET) as Part of the Unemployment Problem

- NEET is a very important to measure for the effectiveness of youth employment approaches in any country or community. Although they remain in a precarious labour market status and at risk of social exclusion during their participation in such programmes, they would not be classified as NEET. For example, youth unemployment rates, despite being available for all EU member states, or rates of young people ‘Not in Employment, Education and Training’ (NEET) as a percentage of the total resident population of the age group, depend to a large extent on the characteristics of the education system (Eurofound, 2012). A study was carried in the UK, by the National Statistics Office (2016), showed that NEET is an issue in 90% of the member states starting with countries as France, Greece, Spain and Italy where its proportion ranges between 25% and 30% of young people who an immigrant/minority background, or living in disadvantaged areas. Many of these youth NEETs vary considerably across the EU between 4.4% of all young people in the Netherlands to 21.8% in Bulgaria (Eurofound, 2012).Studies show that to manage the challenge of NEET, the school-to-work transition, need to be redesigned including the transition from further education colleges to the labour market, Crawford et al. (2011). Crawford and his team carried a similar longitudinal study on the UK and found generally that the trend of youth continuation in education enrolment of ages 16- to 21. However, the average youth employment rate slightly declined, and the use of fixed-term contracts increased, while the share of 16-year-olds who were not participating in education fell.To improve the inclusion in the labour market and human capital accumulation while reducing segmentation and transitions from school to NEET; The European Commission has released selected indicators to monitor the field of youth NEET policy. A ‘Dashboard of 40 EU Youth Indicators’ (European Commission, 2011) was produced in March 2011, listing: Education/Training; Employment and Entrepreneurship; Health and Well-Being; Social Inclusion; Culture and Creativity; Youth Participation; Volunteering; Youth and The World.

2.7. Youth Unemployment as a Global Issue in Knowledge Economy

- The issue of unemployment is very silly in an age with knowledge supposed to be the currency and new trend. It requires the cooperation of regional and national institutions, an in-depth analysis of the problem and the active participation of everyone. Although EU development in the knowledge-based economy; Quintini and Martin (2006) found that between 1995 and 2006 on average youth unemployment fell across OECD countries, however, it improved in more than half of the countries but severely deteriorated in a few. We live in a digital age where modern communication technology has shaped our world, and it has impacted our lives tremendously and is supposed to solve the world's biggest problems. For example, Singularity University in the US is teaching people how to leverage exponential technology to impact 1 billion people positively. This is a knowledge-based era where youth impact can be tremendous if they are well utilised and appreciated. Economic Discussion (2019).Hence, the more youth are employed with the mindset of minimising material consumption and focus on production that integrates knowledge in the output the more possibilities they are expected to get. Due to this change, intellectual labour youth is needed more today in the labour market to re-evaluate the productive age and help towards effective transformation. It is a generation that could benefit more from good technology infrastructure and highly connected mobility business with low-cost internet connections, if employed and their productivity optimised at the right time. Buheji (2018c).With youth continuing not to be employed in the right time and place, we would still have youth not being connected to mobile devices which means a greater loss of potential opportunities. Despite this fact, there are more than half a billion people across Africa now subscribe to mobile services, despite it being the highest continent in poverty. Buheji (2017c).With the rapid evolution of the technology and the demand for a digitally skilled workforce, we call for short today the App generations, governments and education authorities need to adapt to the fast change based on this technology in the education system. This adaptation capacity would reflect on the compatibility of youth to the fast-changing market demands. Eshelman (2015), Buheji (2018b).

2.8. Examples of Youth Unemployment Challenges

- To shed an example of the type of youth unemployment challenges, a review of the published literature about east, west and middle of the world was explored. In the United Kingdom, for example, youth employment found to happen only when there is sustained economic growth. Reducing cyclical volatility in relevance to youth requires a UK balanced growth. This found to effect even the education investment. In the USA, youth unemployment is three times ahead of the elders. The youth unemployment rate is above 5.7%, and about 17% of the nation’s youth are jobless. WEF (2019).In Korea, the study of Kim (2019) mentioned about the most sought-after careers among teenagers and young adults in South Korea are becoming government jobs. This is due to the slowing down of the Korean economic growth in export-driven industries. Kim mentioned about 10 million of graduating youth in the next five years are considering risk-free government jobs. Unemployment among those Koreans of ages 15 to 29 reached 11.6% last spring. It is a level where the Korean president called to be catastrophic, compared what used to be between 3% and 4% just a few years ago. Analysts say part of the problem for young job seekers in South Korea is the widening gap between the quality of jobs at family-owned conglomerates like Samsung and LG and the rest of the players, due to global economic slow.In Algeria, Yahia (2018) carried a study about the evolution of the unemployment rate and growth rate in Algeria during the period 1970- 2015. The overall unemployment rate in Algeria has declined considerably over the last decade falling from 28.3% in 2000 to 9.4% in 2015.The first analysis indicates that this Algerian unemployment decline was due in particularly to the public investment programmes implemented in the period 2000-2015. This public employment programs created about 6.25 million jobs between 1999 and 2008. This economic growth has probably contributed to the fall in youth unemployment, real GDP growth increased from 3% in 2001 to 7.2% in 2003 and 5.9% in 2005, followed by a sharp slowdown in 2006 and 2007 to around 1.7% and 1.6% respectively, partly because the surge in international oil prices affected domestic demand. Howeverm Yahia (2018) reported that the unemployment rate in Algeria (9.4% in 2015) remains high compared to other Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries. For instance, in 2014, the unemployment in Iran is 10.6%, Morocco 10.2%, Turkey 9.2%, MENA countries 8.8%, Venezuela 7%, Indonesia 6.2%, Saudi Arabia 5.6%, Russia 5.1%, China 4.7%, Nigeria 4.8%. Yahia (2018).Hadjivassiliou et al. (2015) examined labour market performance affecting young people in the light of recent policies in Europe, drawing on an analysis of EU Labour Force Survey data 2004-2012. Hadjivassiliou and his colleagues developed a single index measure of labour market performance combining nine variables of labour market inclusion, human capital formation, labour market segmentation and transitions out of education. The idea was that one index would show the performance in relevance to employment capacity and especially youth. No EU Member States achieved full 100 per cent performance on individual dimensions, for example avoiding entirely unsuccessful transitions out of school or achieving full employment of the 15-24-year-olds. The index can be interpreted as measuring the shortfall of achievement across the four key dimensions of inclusion, human capital formation, labour market segmentation and transitions out of the education. Hence institutional change is needed to create effective outcomes in factors associated with young people’s labour market transitions.

2.9. Probability of Youth Staying Unemployed

- When we compare unemployed youth probability of moving into a wage or salary work with the probability of moving to self-employment, we find that married youth individuals, individuals with longer unemployment spells, individuals with more self-employment experience, and individuals with more wealth are more likely to become self-employed instead of taking a wage or salary job upon becoming reemployed. Johansson and Handelshögskolan (2015).To anticipate the results, we find that a long spell of unemployment increases the probability of entering self-employment from unemployment when compared to entering paid employment from unemployment. This also holds after controlling for previous self-employment experience.In countries with large-scale apprenticeship systems, such as Germany and Austria, youth have less possibility of staying unemployed. Youth apprentices are included in the total labour force, because vocational education and training (VET) are delivered primarily by firms. However, unemployment as a percentage of the total labour force in countries with college-based VET is likely to be upward-biased because of the understated denominator (total labour force). In apprenticeship countries, youth unemployment probability risks are understated because the total labour force includes all people in VET.Many youths have the right skills to find fresh work, but factors such as high house prices and housing rents, family and social ties and regional differences in the cost of living make it difficult and sometimes impossible to change the location to get a new job. Many economists point to a persistently low level of new house-building as a major factor impeding labour mobility and the chances of finding new work.In order to reduce the possibility of youth staying unemployed for long times, many governments subsidies for businesses that take on the long-term unemployed – for example, as part of the UK youth contract, payments of up to £2,275 are available to employers who take on young people (aged 18-24) who have been claiming JSA for more than six months. The same thing in Bahrain where employed in specific industries would get more than half of the national youth salary for the first two years. In certain countries in Europe, there is a scheme that would help to lower the tax on businesses that employ more youth or support the employer national insurance contributions.In the last one decade, many developing countries have started to follow the EU programs which encourage entrepreneurship and innovation as a way of creating new products and market demand which could generate new employment opportunities?

3. Methodology

- Youth unemployment is a tragedy that is no one’s fault in particular. It’s a political problem. It’s an economic problem. And it’s a societal problem. Here are three solutions that try to tackle youth unemployment from a few different angles.The current approaches for youth unemployment are synthesised to be either proactive or reactive approaches. Then these current approaches are compared to the published approaches of Inspiration Labs and how it addresses youth unemployment as a socio-economic problem. A holistic, practical solution is extracted from both the synthesis of the current literature and latest labs regarding mitigation of youth unemployment as a proactive way to avoid a foresighted crisis.

4. Case Study

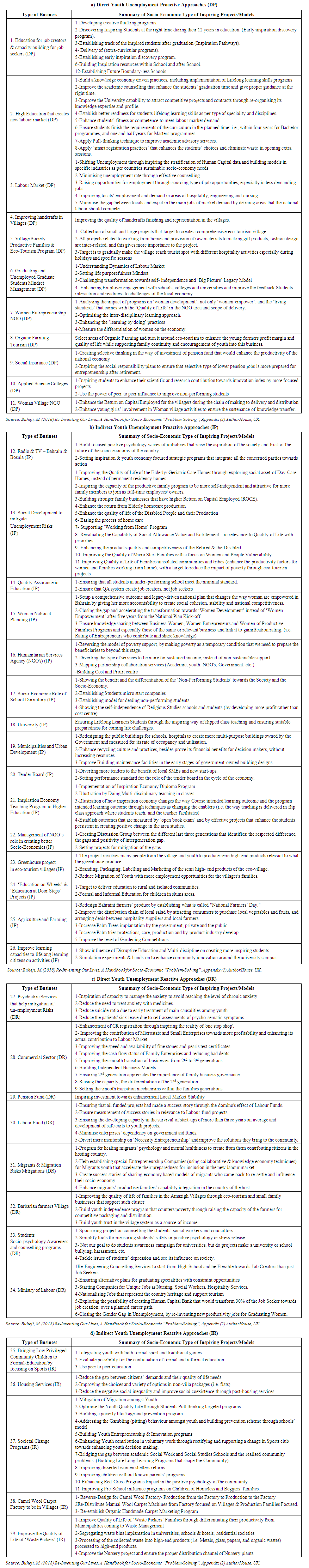

- The international inspiration economy project which started in September 2015 focused on different socio-economic problems, like poverty, women advancement, youth migration and quality of life. One of the repeated problems solved, through models only is the mitigation of youth unemployment, which is called ‘Youth Unemployment Mitigation Labs’. The idea of these labs was to reduce youth unemployment or its negative influence through proactive models that could help to solve the complexity of this mega socio-economic problem. Buheji (2018e).The following list of Table (2) shows the different socio-economic problems or challenges solved in relevance to youth unemployment and the mitigation approaches followed in the different communities, countries visited and in different situations.

| Table (2). List of Youth Unemployment Mitigation Labs carried out by the researcher from September 2015 till March 2019 |

5. Discussion

5.1. Causes of Unemployment – Synthesis from Literature

- The reviewed literature shows that prime causes of unemployment can’t be list under one category. Although youth don’t have much difficulty about occupational immobility, they are today under a consistent challenge to learn new skills and adapt with the high speed of new industrial developments along with the change in technology and geographical immobility. The other cause of youth unemployment is frictional unemployment which is taken by the individuals while they change their job. The literature also shows that the challenge comes from the type of approaches followed for filling the gap of youth unemployment. i.e. Youth might have seasonal unemployment which takes place due to seasonal change in the job nature as in tourism, fruit picking and hospitality. Hence, this doesn’t solve the problem effectively.Casual youth employment is a type of employment that comes in, for employees who work on a day to day basis or on short term contracts. Most of the places where casual employment exists for young people are usually based on hard labour as dockyards, market places and rarely film or tech industry.

5.2. Effects of Youth Unemployment

- The literature shows great influence of youth unemployment on the economy and the socio-economy. This is mainly because youth effects nations in their capacity for collecting tax revenues, increasing the supply cost and enhancing welfare cost. With youth being available on the job, we can lower wages, ensure the control of prices on goods and services improve the training quality vs cost, improve the living standards, increase the investors’ confidence and minimise knowledge or skills drain.The issue of youth unemployment doesn’t only affect the SDG achievement, but goes further as shown from literature to affect the country’s economic development, especially they are a human capital that makes one-third of the working-age population of all the emerging and developing economies. Since youth in these economies are mostly NEET, i.e. more than 20% of them are neither employed, nor in school or training, this would raise the rate of youth age in entering the market by at least three %t.

5.3. Effect of Current Youth Unemployment Policies

- The reviewed literature draws on both analyses of different literature that came from both macroeconomics and microeconomic policies. Despite the diverse policies that address this issue, challenges in the youth labour market still persist. There are three major types of public policy: regulatory policy, distributive policy, and redistributive policy. Each type has its special purpose when it comes to youth unemployment. A major goal of all these policies is to maintain order and prohibit behaviours that endanger society. The policies as shown from the literature review either try to accomplish the goal of guiding organisations towards better youth employment or engaging organisations and youth into actions that would positively affect the socio-economic and socio-political order. Other distributive policies target to enhance the economic activities and businesses that would trigger more youth employment and create a more suitable market for them while redistributive policies would focus on promoting equality that ensures societal wealth from youth employment and capitalises on the benefits that come from such programs.In general, once from the synthesis of the reviewed literature, one could say there is no clear evidence for approaches that are made to selecting the right policies based on experimentation or labs. With the high speed of advancement in the technology and socio-economic instability, policies seem not capable of matching the needed gap closure, especially with the slow development of the capacity of the education that meets the market demands. Therefore, testing the approaches through the effectiveness of economic policies may help the young better cope with such market disruptions.

5.4. Approaches to Inspiration Labs vs. Current Approaches

- The inspiration labs followed different approaches to mitigate youth unemployment as a socio-economic issue. The inspiration labs had the following two main approaches:

5.4.1. Proactive Approaches

- These approaches address the distributive (the economic development) and redistributive (economic equality) policies; as in the education for job creators and capacity building for job seekers. The proactiveness of these approaches can be either mostly direct proactive, or indirect proactive approaches.The other proactive approaches are working on inspiring students to enhance their scientific and research contribution towards innovation index by more focused projects. The approach target to prepare youth to take more jobs relevant to scientific and research-based jobs.One of the focused approaches that could be retrieved from the inspiration labs case study is the selective investment towards enhancing youth role in the local market and setting life purposefulness mindset that suite this initiative. The other unique proactive approach focuses on enhancing the youth employers’ engagement with schools, colleges and universities and improve the youth interaction and readiness to the challenges of the local economy. All the proactive approaches work to manage the challenges towards the transformation of self-independence and the ‘big picture’ legacy model.

5.4.2. Reactive Approaches

- The reactive approaches work to mitigate the risks of youth unemployment and help to close the gaps of any major defect relevant to youth employment or employability efforts and preparations. The approaches here either direct reactive or indirect reactive approaches. For example, the provision of youth-focused psychiatric services that help to eliminate the negative impact of youth unemployment is one of the proactive and still reactive approaches. Same thing when ensuring that all students in under-performing school meet the minimal standard.Part of the reactive approaches is also ensuring that all youth funded projects have made a success story and properly shared amongst youth in the labour market. In continuation of this establishing special entrepreneurship companies (using collaborative and knowledge economy techniques) for youth, migrants accelerate their preparedness for inclusion in their new labour market and eliminate their immersion in the cycle of poverty.The strong approaches of the inspiration labs as per Table (2) is the efforts on shifting unemployment through inspiring the stratification of human capital data and building models in specific industries, as per countries sustainable socio-economy needs. These approaches also found to optimise the youth quality life through selectively targeted programs.

6. Conclusions

- To solve the unemployment problem, we need a holistic approach that ensures the development of policies but based on experiential learning and industrial friendly approaches that accept the facts and manage to mitigate the realised risks by actual problem-solving labs and models. Such an approach could speed up the achievement of the UN-SDG regarding youth empowerment and solve the huge gap in relevance to youth unemployment. The paper shows there are many direct and indirect proactive and reactive approaches to the unemployment of youth that reached a source status and percentages in even developed countries. These approaches can go beyond waiting for decision makers and can start from social, or socio-economic driven business models.The inspiration labs cases listed in the table (2) show that we humans today should and could bring in more creativity to the issue of youth unemployment, through proactive and reactive approaches that could change our mindset in dealing with such complex socio-economic problem. The case study presents an opportunity for many countries and international organisations working with youth, or on the issue of unemployment, youth migration, or even youth quality of life. It is a list of approaches that might help many communities, directly or indirectly, from different perspectives on how to be both proactive and reactive regarding the issue of youth unemployment and specifically for those youth in NEET, i.e. not in education and not working. Despite, the limitations of this study which was carried only in a longitudinal period of 3.5 years and in specific countries, the variety of approaches present many rich possibilities that could be generalised to face the coming economic downturn in both developed and developing countries. The labs presented certainly present a potential shake-up of the classical policies followed and the solution proposed in dealing with such alarming problem that hinders the current and coming generation contribution to the global development, taking that we are living in a thriving and yet turbulent knowledge and innovation-based economy. The holistic approach explored in this paper shows new disruptive way to solving such communities’ challenges and it is certainly would open more desires for more future research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML