-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2018; 8(5): 221-229

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20180805.03

Military Expenditure and Human Capital Development in Nigeria

Obasi C. N., Asogwa F. O., Nwafee F. I.

Department of Economics, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Obasi C. N., Department of Economics, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Military expenditure has been recently argued to displace expenditure on human capital development indicators. Though no economic theory has firm backing on exact relationship between military spending and human capital development spending, most empirical studies claim the possibility of negative relationship between the two. This study investigates the impact of military expenditure on human capital development in Nigeria. The study used annual time series data from 1970 to 2014. Adopting Autoregressive Distributive Lag model (ARDL) and performing the necessary pre- and post-diagnostic tests, the results show that while military expenditure has insignificant negative relationship with education sector component of human capital development indicator (gross school enrolment rate), it however has significant negative impact on health sector component of human capital development indication (infant mortality rate). It was concluded that military expenditure has negative influence on human capital development. Based on these findings, it was recommended among other things that while government maintains simultaneous spending on both the military and on human capital development, it should be mindful of its dwindling spending on health sector and at the same time improve its spending on the education sector.

Keywords: Military expenditure, Human capital development, Development indicators

Cite this paper: Obasi C. N., Asogwa F. O., Nwafee F. I., Military Expenditure and Human Capital Development in Nigeria, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 8 No. 5, 2018, pp. 221-229. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20180805.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

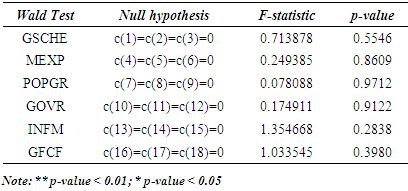

- The key responsibilities of any performing government is to ensure the safety of lives and property in any given society through a strong military mechanism, involving strong commitments to military expenditure in order to bolster security and counter threats. Military expenditure is a rough measure of the level of government financial allocations for military purposes. As such, it can measure the priority given to defence as a means of achieving security as formulated in national security doctrines [1]. Strong and efficient armed force, strong enough to guarantee national peace and security is indispensable for the economic progress of a nation. This argument anchors on the premise that defence is a critical sector that contributes to economic development by ensuring internal and external stability [2].Today, world military expenditure has skyrocketed- much bigger than ever with an estimate of $1,738 billion per annum, with the United States determining the trend as the biggest spender globally owing to her rapidly increasing military expenditure, as one of the top spenders with about $711 billion military expenditure, followed by China, Russia, United Kingdom, France, Japan, India, Saudi Arabia, Germany and Brazil at $143, $71.9, $62.7, $62.5, $59.3, $48.9, $48.5, $46.7 and $35.4 billion respectively. The top ten big military spenders take about 74.3% of military expenditure globally, the United States alone accounts for 41%. According to World Bank and the Office of Disarmament Affairs (ODA), the amount spent on the defence sector globally is equivalent to $4.7 billion daily or $249 per person, and just about 5% of this amount annually is needed to achieve and sustain the Millennium Development Goals [3].Military expenditure is certainly not without effect on resource allocation and economic growth. The effects are multiple and often offset each other. There are considerable literatures on the cost of military expenditure, resulting from its adverse effect on economic performance of the overall economy. There is diversion of resources that would have been used for other developmental needs; the resources used for military equipment (either producing or importing) can alternatively be used for building hospitals, schools or for providing civilian goods, showing the extent to which the economy foregoes the opportunity cost to commit these resources for alternative peaceful uses. In most developing countries (Nigeria inclusive), the percentage of military expenditure as a share of GDP is high contrary to health or education expenditure as a share of GDP. High military expenditure and ongoing conflicts (terrorism, insurgency, political conflict, ethnic conflict religious crisis and border violent amongst others) in developing countries have become a major impediment to the growth and development of the system. Public expenditure on health is one of the biggest challenges in West African region, thus, enhancing the productivity of health expenditure in developing countries has been a controversial debate and a key public policy challenge over the years, as there is very high infant mortality, life expectancy in this region is estimated to be among the lowest in the world. Human capital development does not only aid economic growth via good health services, it has been argued that education contributes to skill acquisition through school enrolment; this enables individuals to improve on their productivities. The role of education is pivotal in comprehending, controlling, altering, and recreating of human environment [4]. According to [5] education improves health, and productivity, which implies that health and education has a link with economic development of a country. In developing countries not only is government allocation to health sector traditionally low [6], but developing countries are where the interaction of economic decline and continued high rates of population growth meant that the proportion of the school age population in school declined by 10%. For instance, in 2007, while secondary school gross enrolment ratio stood at 101% in high income countries the value was 38% for low income countries.Nigeria is a developing economy with expanding financial and social service sectors. According to [7], Nigeria worth about $568.51 billion in 2014 GDP and represents about 0.92% of world economy, ranking 26th in the world and 1st in Africa with an estimated population of about 177.8 million in 2014. The country has however witnessed unusual huge increase in public expenditure in the last few years. For instance, from1970 to 2012 total recurrent expenditure has increased from ₦716.10 million to ₦3,365,760.00 million respectively. This increase however, has not translated to any significant growth as more Nigerians are poor today as was never before [8]. Available statistics from [9] shows that military expenditure were ₦444.6 billion, ₦233 billion, ₦264 billion, ₦348 billion, ₦921.91 billion, ₦1,055 trillion and ₦968.127 billion from 2008 to 2014 respectively, showing an upward trend in defence expenditure.Increase in government expenditure is meant to boost the economy [10], but despite the continuous rise in government expenditure in Nigeria the economy is still stunted, Nigeria still faces rising incidence of poverty and is ranked among the poorest economy with poor public service delivery [11]. The issue relating to effective and efficient public service delivery are critical for Nigeria because it is a country where the public sector controls enormous wealth coming from oil revenues leading to increase in public expenditure levels in the tune of over 40% of gross domestic product (GDP), yet there is very little to show for this in terms of actual impact on poverty, health and education of the masses, these forms one of the major factors contributing to her low per capita income. Nigeria channels a large part of her revenue to the defence sector with less recognition to the important role played by human capital [12].As indicated in Figure 1, military expenditure consistently overshadowed both education and health expenditure from 2001-2014 except for 2006, 2007 and 2013 when it was slightly overtaken by education expenditure. This tells us that expenditure in health and education sectors has been fluctuating. Increasing military expenditure in Nigeria will not only divert the resources from other sectors but the adverse effects of raising military expenditure in developing economy like Nigeria is likely to worsen the existing poverty since almost all the military hardware are imported. The debate on the impact of defence expenditure on development of human capital in Nigeria in recent times draws attention to these questions. How does military expenditure (increase or decrease) affect human capital development in Nigeria; most importantly health and education sector which are pointers to human capital development and how this in turn affects the growth of Nigeria’s economy? There is the insinuation in literature that successive governments in Nigeria favoured the defence sector with high military spending at the expense of other sectors. This by implication is said to impact negatively on Nigeria human capital development. This has given rise to key pertinent question; does military expenditure impact negatively on Nigeria human capital development? Addressing this question will give a new lease to effective policy-making in the country. It will aid to establish the needed link between the current rate of military expenditure and the development of human capital in Nigeria. This critical issue forms the focus of this study. The objective of the study is: To examine the impact of military expenditure on human capital development in Nigeria.

| Figure 1. Government expenditure on defence, education and health sectors |

2. Review of Literature

- The argument about military expenditure began when [13] showed empirical evidences that defence burden has advantages on economic growth. Benoit using the Keynesian theory found that in developing countries that there is a positive relationship between military expenditure and economic growth. According to Benoit, military expenditure stimulates rather than depresses the economy. Subsequently, studies sprang up after Benoit’s work to challenge his findings; however, so far no results or findings have emerged to show a clear-cut on the nature and extent of effects of military expenditure on economic growth. Following the study of Benoit, some of the studies are of the view that military expenditure should be increased; some of the studies are of the view that human capital should be increased while some are of the view that either of the variables can be increased as they are both relevant to economic growth.[14] carried out a research on the relationship between military expenditure and economic growth in United States of America using the Autoregressive Distributive Lag (ARDL) bounds testing approach to cointegration tests for the period 1970-2011. The results showed a negative relationship between military expenditure and economic growth.[15] attempts to examine the effect of conflict and military expenditure on three levels of school performance, namely, school enrolment rate, school completion rate and children out of school rate, in five major countries in South Asia over the period from 1980 to 2013 using panel regression methods. The findings of this study are that conflict and military expenditure create an obvious threat to children’s education in South Asia. Therefore, the government, policy-makers and international educational organizations should take effective measures to increase educational opportunities in conflict affected areas through affirmative ways to minimize conflict which can subsequently decrease military budget.In the same year, [16] re-examined the relationships between military expenditure and economic growth in China, using an annual data for the period 1980-2011, the study used an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) to test for the long run and short run relationships. The results however indicated an inverse relationship between economic growth and military expenditure in the short run while the long run results showed that the correlation among the variables is inconclusive.[17] carried out a study using conflict onset as an instrument for military expenditure in an endogenous growth model for a panel of African countries from 1989-2010. The empirical analysis showed that endogeneity is likely to be an important issue. With the use of instrumental variable (IV) estimation which provided a greater significant negative effect of military expenditure on growth than OLS. This implies from the study that earlier studies have underestimated the damaging effects of military expenditure. [18] in a paper with the topic “The Interaction between Defence Spending, Debt service Obligation and Economic Growth in Nigeria” revealed that states that enjoy relative peace seem to reap more economic benefits from defence expenditure while those suffering from conflict and poverty pay higher economic cots for their defence. They recommend that government of developing nations like Nigeria should spend more on human capital development which is the bedrock of every society rather than on military, through this the whole society is developed. Thus, scholars such as [18] opined that military expenditures as a share of total government expenditures had a negative relationship with expenditure on human capital development. Also, [19] employed an Error Correction Model to examine the relation between military spending and economic growth in Nigeria, they found out that military expenditure has a negative effect on the level of economic growth in Nigeria. [20] examined the relationship between the components of military expenditure and poverty reduction in Nigeria between 1990 and 2010. Using Dynamic Ordinary Least Square (DOLS) method, four models were estimated, two in which poverty index constructed from human development indicators serves as dependent variable and the others in which infant mortality rate serves as dependent variable. The study showed that military expenditure per soldier, military participation rate, trade, population and output per capita square were positively related to poverty indicator and, military expenditure, secondary school enrolment and output per capita were negatively related to poverty level. This confirms the trade-off between the well-being and capital intensiveness of the military in Nigeria, showing the vulnerability of the poor among the Nigerians. [21] examined the proposition that military expenditures crowd-out expenditures on education in Nigeria during the period 1973-2006. Using a VAR model, he forecasted error variance decomposition and impulse response functions derived from the VAR he investigated the dynamic relationship between military expenditure and expenditure on education. His result indicates that military expenditure in Nigeria crowds-in expenditures on education. He also revealed that there is a positive and significant relationship between military expenditure and education expenditures and a negative and significant relationship between expenditures on education and economic growth as well as military expenditure and economic growth.[22] investigated on the relationship between human capital developments efforts of Government and economic growth in Nigeria, seeking to understand the impact of government recurrent and capital expenditures on education and health in Nigeria and their effect on economic growth. Using secondary data, the augmented Solow model was also adopted in the study. The level of real output was used as the dependent variable while the explanatory variables are government capital and recurrent expenditures on education and health, gross fixed capital formation and the labour force. The findings from the study showed a positive relationship between government recurrent expenditure on human capital development and the level of real output, while capital expenditure is negatively related to the level of real output. The study however recommended appropriate channelling of the economy’s capital expenditure on education and health to foster economic growth.[23] evaluates human capital development and economic growth in Nigeria by adopting conceptual analytical framework that employs the theoretical and ordinary least square (OLS) to analyze the relationship using the GDP as proxy for economic growth; total government expenditure on education and health, and the enrolment pattern of tertiary, secondary and primary schools as proxy for human capital. The analysis confirms that there is strong positive relationship between human capital development and economic growth. The study recommended that there is a need to evolve a more pragmatic means of developing the human capabilities, since it is seen as an important tool for economic growth. Also proper institutional framework should be put in place to look into the manpower needs of health and the education sectors.[24] examined the macroeconomic impact of defence expenditure on economic growth in Nigeria, capturing from 1970 to 2008, using a simulation approach. In his study, a macroeconomic wide model was developed using five blocks consisting of 18 endogenous equations. The result from the study showed that defence expenditure has a significant impact positively on public investment, non-oil export and economic growth as a whole, also the analysis from the estimated macro econometric model further showed that defence expenditure has a significant impact positively on oil and gas output, agriculture and social services sector. The author is of the view that judging from his analysis that increases in defence spending aids economic growth. [25] employing the Feder-Ram studied the relationship between the level of economic growth and military expenditure in Nigeria between 1977 and 2006. The result showed a unidirectional causality running from economic growth to military expenditure. [26] supported the view of Dunne and Mohammed he noted that many less developed countries have tended to reduce the social wage including educational expenditure to enable them sustain or even increase military expenditure. The studies reviewed showed divergent findings. A number of studies found a negative relationship between military expenditure and economic growth [27, 21, 18, 19, 14] while some showed a trade-off such as [28, 20]. On the other hand, some research showed a mixed result; that military expenditure either has a positive or negative relationship between human capital and economic growth [29, 30, 31, 32, 16, 33]. Some literatures showed that military expenditure affects school enrolment rate [34], while some studies found a non- linear relationship between military expenditure and economic growth [34, 35]. It is interesting to note that apart from [21] that treated a part of human capital development using education as a proxy, none of the studies has used health and education as a proxy for human capital development to estimate the effect of military expenditure on human capital development.

3. Methodology

3.1. Theoretical Framework

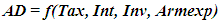

- Based on above reviewed theoretical literature, the study adopted the theoretical framework of the Keynesian. The Keynesian theoretical framework sees a proactive state, a state which uses military spending as one aspect of state spending to increase output through multiplier effects in the presence of ineffective aggregate demand. In this way increased military expenditure can lead to increased capacity utilization, increased profits and hence increased investment and growth. This framework was developed by [36] and has provided the basis for most of the subsequent studies of the economic impact of military expenditure.According to [37] the model argues that a capitalist state can minimize the consequence of economic recession when the following four activities are adopted: tax reduction, low interest rates, investment subsidies and increase in armament expenses. While the first three factors can strongly induce economic agents to invest for profit, the last will guarantee the safety of such investment and encourage future expansion. The framework further demonstrates that while a fall in tax and interest rate (Tax and Int) stimulates aggregate demand, rise in investment subsidy and armament expenses (Inv and Armexp) will lead to rise in aggregate demand. Thus, the model can be represented as follows;

| (1) |

3.2. Model Specification

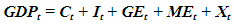

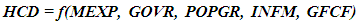

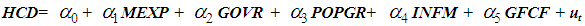

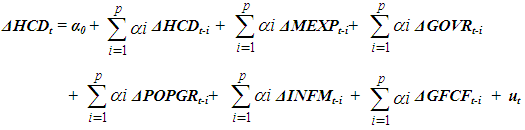

- The military expenditure-economic growth model regression employed by [14] in the United States of America was adopted and modified in this study. The study models an ARDL version of the Keynesian framework to show that GDP comprises consumption (Ct) of the household sector, investment (It) of the firms, government expenditures which can be split into non-military (GEt) and military (MEt) sector and the international sector (Xt) as follows;

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

4. Results Presentation

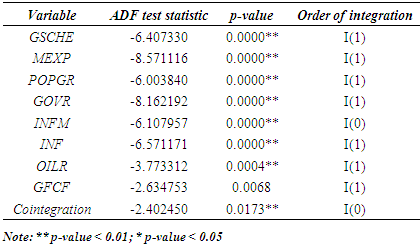

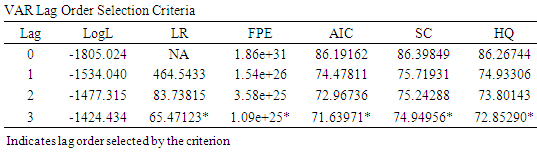

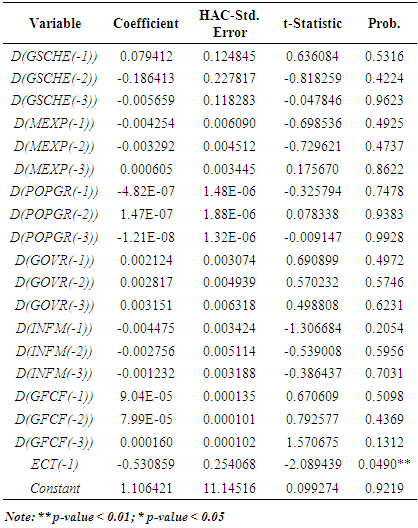

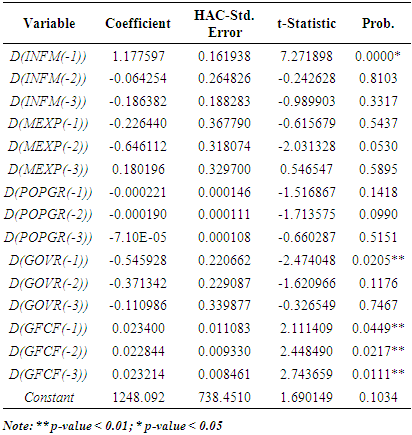

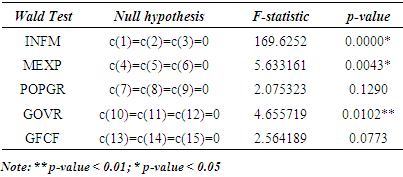

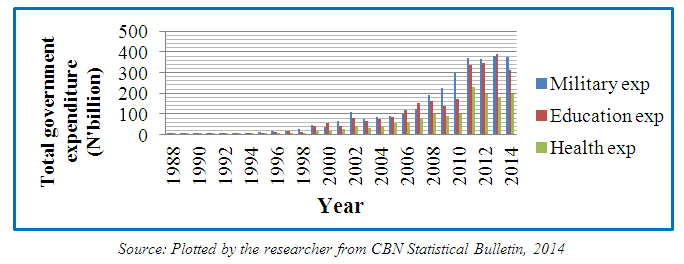

- This section presents the interpreted regression results alongside results of basic diagnostic tests carried out in this research. Results are presented and analysed based on the models specified earlier. The regression results examined the impact of military expenditure on human capital development indicators (gross school enrolment and infant mortality) in Nigeria using the econometric software Eviews 8. However, the researcher performed pre-estimation time series test such as Unit Root and cointegration. Variables of interest are as defined earlier. The Unit Root test in Table 1 shows that the dependent variables (GSCHE and INFM) and some of the independent variables (MEXP, POPGR, INF and OILR) are integrated of the same order. That is, they are stationary after first difference (I(1). Based on this, the researcher proceeded to test for cointegration as presented in Table 1. The ADF test t-statistic value of -2.402450 with p-value of 0.0173 which is significant at 5% level reveals that there is cointegration between dependent and independent variables in the model of this study. This means that there is need to introduce an Error Correction Mechanism in order to capture the short-run and long run dynamic relationship between the variables.

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions & Policy Implications

- The overall idea of the paper was to examine the impact of military expenditure on human capital development in Nigeria. The study was undertaken to ascertain how military expenditure (increase or decrease) impacted negatively on Nigeria’s human capital development most importantly health and education sector which are pointers to human capital development and how this in turn affects the growth of Nigeria’s economy. The results of the study revealed mixed effects of military expenditure on human capital development. Essentially, the study found that military expenditure reduces spending in the health and education sector and consequently deteriorate essential human developmentn indicators-gross school enrolment and infant mortality but the effect is more on the health sector. This finding by the study has policy implication, more so as the developing countries race to achieve the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of which health and education are key target goals. The government should therefore, as a matter of deliberate policy initiative try to strike a balance between military expenditure and improvement in the human capital sector by trading some resources off to education and health sector to improve the health indices.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML