-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2018; 8(4): 202-208

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20180804.03

Can Oil Prices Forecast the Exchange Rate?: Evidence from Algeria

Ahmed Smahi1, Kamel Si Mohamed2

1Department of Economics, University of Tlemcen, Algeria

2Department of Economics, Ain Témouchent University, Algeria

Correspondence to: Ahmed Smahi, Department of Economics, University of Tlemcen, Algeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Because the pricing of crude oil is made in American dollars internationally, changes in oil price directly affect the exchange rates of the countries. For this reason, the purpose of research is to highlight the relationship between oil price and nominal US Dollar/Algerian Dinar exchange rate through an empirical analysis using a VECM Model (Vector error correction model) upon monthly data for the period 2008-2015. Results show that a cointegration relationship is detected between oil and exchange rate in Algeria, with bilateral trend causality in short and long run time horizon. Furthermore, the relationship of the out simple predictive indicates that a change in oil price would tend to depreciate Algerian Dinar against US Dollar. This negative impact emphasizes how the Algerian dinar is a non-oil currency and explains how the foreign exchange receipts from hydrocarbon exports help swell Algerian public spending that would cater for public budget deficit curtailment.

Keywords: Oil Price, Algerian Dinar, Exchange Rate, VEC Model

Cite this paper: Ahmed Smahi, Kamel Si Mohamed, Can Oil Prices Forecast the Exchange Rate?: Evidence from Algeria, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 8 No. 4, 2018, pp. 202-208. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20180804.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

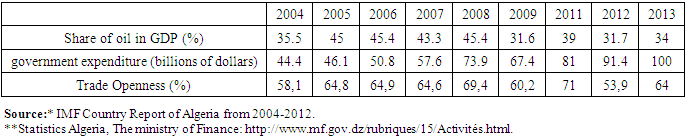

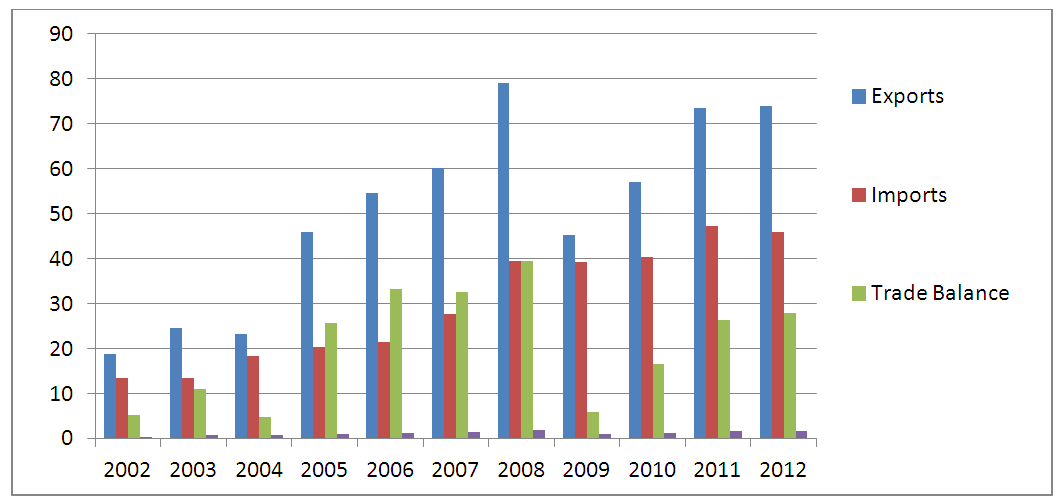

- In oil exporting countries, the evolution of the price of oil is one, if not the most, important factor to be considered in economic policy decisions. These economies, whose GDP and exports are dominated by petroleum, may face costly and persistent macroeconomic instability when they fail to find optimal responses to oil price shocks Policymakers and academics have frequently discussed the link between oil prices and exchange rates in recent years—particularly the idea that an appreciation of the US dollar triggers a dip in oil prices. However, oil and gas are considered as an important source of national wealth and economic growth around the world, the prevailing view is that there is a positive impact of oil and gas rent on promoting economic growth. In the case of the Algerian economy, Algeria is the third largest oil-producing African country and the 17th largest oil producer in the world with a daily production capacity of 1.7 million barrel (U.S Energy Information Administration, 2015). This country has a proven oil reserve of about 12 billion barrels, the third largest reserve in Africa. Furthermore, in 2013, Algeria was ranked the eighth largest natural gas exporter in the world and the third largest gas supplier to Europe (Smahi et al, 2015). Since the discovery of oil fields in Algeria in 1956, the oil sector has been the mainstay of this country's economy. Indeed, oil exports amount to 98% of total exports and around two-thirds of government revenues (World Bank, 2016), this sector accounted, between “2002 – 2014”, more than 40% of GDP and 46 to 70% of government revenue, see Figure 1, while trade openness, see Table 1, exhibits a high figure of 60% in the same period. As far as the Algerian exchange rate is concerned, the central bank adopted, since 1996, a managed floating exchange rate after a long experience with the former regime (1974-1995) that was built upon a strong concentration of the US dollar that played an important role due to its 98% in hydrocarbon export receipts. Between January 2003 and January 2013, the Algerian exchange rate has varied continuously; from January 2003 to September 2008, the U.S dollar depreciated monthly against the Algerian Dinar by about 19%, followed by a depreciation of 6% during the financial crisis. Between January 2010 and January 2013, the Algerian dinar depreciated against the U.S. dollar by 4.2%. Oil price showed during these periods’ remarkable changes with +152%, -9%, +37%. So, what is Algerian dinar worth in US dollars is always the central question, since the US dollar is the international reserve currency. After the end the first decade of the new millennium, we can be seen clearly around 40% of business transaction carried out through the black market in informal sector when the gap between the official exchange rate of the Algerian Dinar against the Euro and that observed on the black market has exceeded to 40%; Bouteldja et al (2013). In the same sense, Salah et al. (2015) studied the relationship between oil price and the black market exchange rate US Dollar/Algerian Dinar through an empirical analysis using an (Error Correction Model upon quarterly data for the period 1975-2003. Results show that a cointegration relationship is detected between oil and black market exchange rate in Algeria, with unilateral trend causality in short and long run time horizon from oil prices to black market exchange rate. This paper presents the implications of the oil price fall in the exchange rate in Algeria. Precisely, it is a matter of checking the relationship between oil prices and the exchange rate dinars against the dollar using the VECM model.

2. Theoretical Background

- Many recent studies also find that the relationship between exchange rates and the price of oil has become more time-varying, in particular after 2009. The influence of oil prices on the exchange rate movements is studied early by Paul R. Krugman (1980) and Golub (1983). They conclude that an oil exporting (oil-importing) country may experience exchange rate appreciation (depreciation) when oil prices rise and depreciation (appreciation) when oil prices fall.As the Algerian economy is highly vulnerable to oil price and US dollar fluctuations, we shall investigate, in this section, the dynamic relationship between oil price and exchange rates.Firstly, Oil price plays a strategic role in the global economy. Many studies have highlighted its different impacts on macroeconomic variables such as GDP growth, unemployment rates, inflation, Stock market... (see: Rasche, R. H. and J. A. Tatom (1977), Darby (1982), Hamilton (1983, 1996, 2003), Lee et al. (1995), Rotemberg and Woodford (1996), Eltony and Al-Awadi (2001), Brown and Yücel (2002, 2010), Blanchard and Gali (2007), Bjørland (2008), Chongfeng Wu and Li Yang (2012), Basher and al. (2012)).Secondly, the U.S. dollar is the most important currency in the world economy. It plays a major role in the pricing of oil and other commodities in the financial market. The domination of the US dollar in international trade as a currency commodity lets this currency serve as a central currency in the exchange rate arrangements of many countries in each area (Linda S. G 2010).Therefore, in the past years, particularly before 2002, oil price and US Dollar were moving in the same direction, when the US dollar rises, the price of oil is pushed up, and conversely, when the oil price increases, the US Dollar is appreciated. Since this period, the relationship between the two variables has changed because of the advent of many factors such as oil companies’ targets, the role of the Euro currency, geopolitics, alternative sources of energy, speculators and Federal Reserve policy, and so forth…In contrast, oil prices have risen while the dollar continued to weaken against other major currencies and the depreciation of the dollar could explain, therefore, the increase in oil prices. Since 2002, the price of a barrel of oil has increased fourfold, moving from $26 in 2002 to $107 in 2012. On the other hand, the U.S Dollar/Euro declined annually from 0.944 $US to $1.43 in 2010. Hence, many studies believe there are negative reverse causality between the U.S dollar and oil price during the last period (See, Coull, 2009, Verleger (2008), Setser (2008), Virginie (2008), Akram.f (2008), Sadek and Michel Terraza (2007), Bénassy-Quéré, et al. (2007)). The study of Chen and Rogoff (2003) detected a strong and stable influence of the US dollar price of non-energy commodity exports on the real exchange rates in two countries (Australia, New Zealand). Joyce and Kamas (2003) used a cointegration technique to arrive at the conclusion that there is a relationship between oil price and exchange rate in Colombia and Mexico. Akram (2004), found out that there is a non–linear negative relationship between oil price and the Norwegian Krone over the sample between January 1986 and August 1998. Furthermore, this negative correlation varies along with the level and the trend in oil prices. On the other hand, Koranchelian (2005) finds that in the long-run, Algeria’s real exchange rate is time varying, and depends on movements in relative productivity and real oil price. Issa et al. (2006) pointed out in their study the depreciating effect of the energy price on the Canadian dollar before 1993 and the appreciation of the Canadian currency after this year. Zalduendo (2006) used a vector error correction model to determine the impact of oil prices on the real equilibrium exchange rate in Venezuela. Habib & Kalamova (2007) investigated whether the real oil price has an impact on the real exchange rates of three main oil-exporting countries: Russia (1995-2006), Norway and Saudi Arabia (1980-2006). In the first country, the authors found a positive long-run relationship between the real oil price and the real exchange rate. On the Contrary, for Norway and Saudi Arabia, results show that there is no impact between the two variables.In Nigeria, many studies have used different types of empirical methods and examined the impact of oil price on exchange rate. While, Olomola and Adejumo (2006) observed a positive impact where the oil price Shocks led to an exchange rate appreciation, Iwayemi and Fawowe (2010), and Adeniyi (2011) presented a negative relationship between oil price and exchange rate. In the other hand, analyzing five OPEC countries, Yousefi and Wirjanto (2004) provide evidence that crude oil export prices respond positively to US dollar depreciations. More than, Englama (2010) used VAR and Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) to find the effect of oil price volatility on exchange rate volatility. Koranchelian (2005) estimates a long-run equilibrium real exchange rate path for Algeria, he find that the Balassa-Samuelson effect together with real oil prices explains the long-run evolution of the equilibrium real exchange rate in Algeria. Empirical result found that in the long-run, Algeria’s real exchange rate is time varying, and depends on movements in relative productivity and real oil price. Korhonen et al. (2007) estimated the real exchange rate in OPEC countries from 1975 to 2005 and three oil-producing Commonwealth Independent States (CIS) from 1993 to 2005 using panel co-integration methods. Their results show that real oil price has a direct effect on the equilibrium exchange rate in oil-producing countries. Yue-Jun Zhang et al. (2008) conclude that U.S. dollar has an impact on oil prices over the long-term but no significant impact in the short-term. An early study by Zhang (2008), which analyzes the period between 2000 and 2005, finds a long-term equilibrium relationship between oil prices and euro/US dollar exchange rates, but reports little evidence for risk or volatility spillovers. Similarly, Nikbakht (2010) studied the long-run relationship between real oil prices and real exchange rates from 2000 to 2007 by using monthly panel of seven OPEC countries (Algeria, Indonesia, Iran, Kuwait, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela). His result show there is a long-run and positive linkage between real oil prices and real exchange rates in the OPEC countries. Chen and Chen (2007) carried out a similar analysis for G7 countries and they found a long run relationship between real oil prices and real exchange rates. Colemanet all (2012) found that shocks in the real price of oil are particularly important in determining the real exchange rates, even in the long run for a pool of African countries. Beckmanna and Czudaj (2013) pointed out in their study causality relationship between from effective dollar prices to oil prices through Markov-switching vector error correction model. Benhabib et al. (2014) studies the relationship between oil price and nominal exchange rate in Algeria for the period of 2003-2013 using cointegration analysis and VAR model on monthly data. They find that there is no cointegration relationship between the variables however, unlike the other studies, VAR analysis shows that increasing oil prices lead Algerian currency to depreciate. Benhabib et al. (2014) explains this as the effect of Algerian exchange rate policy which is focused on increasing public spending.Ferraro, Regoff and Rosi (2015) investigated the existence of very short term relationship at the daily data between commodity prices and exchange rate, with their results indicated the out of sample forecasting have been appropriately taken into account. Blokhina et al (2016) study the relationship between oil price and the exchange rates in Russian Federation. The regression model has accurately shown a close interrelation between the currency rate of dollar to ruble and oil prices.

3. Model and Methodology

3.1. Data Source

- In our analysis, we make use of two macroeconomic variables: oil prices (oil) and US dollar/Algerian Dinar (US/DZ). The sample comprises 85 Monthly observations for the period 2008 - 2015. The sources of these variables are collected from different issues of International financial Statistics, IMF and world development indicators.

3.2. Definition of the VECM Model

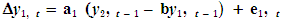

- In this case, non-stationary and bilateral co integrated series, the vector error correction (VECM) would be best to use in this case and for forecasting systems of interrelated time series and for analyzing the dynamic impact of random disturbances on the system of variables.The mathematical representation of a VECM is:

| (1) |

| (2) |

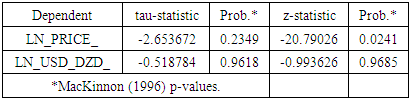

3.2.1. Analysis of Co-integration Tests

- In order to explain the relationship between oil price and the Algerian exchange rate in long run, Engle and Granger (1981, 1987), in their paper, estimated cointegration of non-stationary time-series variables for demonstrating the existence of cointegration between two macroeconomic.

3.3. Results and Comment

- Before presenting the results from the empirical VEC Model, we shall be applying the following econometric step:-Test the stationary of the time series data by Augmented Dickey-Fuller& Philips and Perron; Analysis co-integration tests; Causality test; Forecasting exercise.

3.3.1. Stationarity Tests

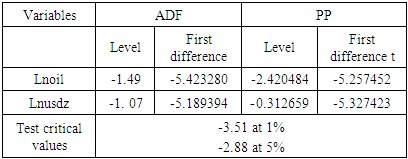

- Most classical econometric estimations as least square method (GLS) based on non-stationary time series produce spurious regression and statistics may simply indicate only correlated trends rather than a true relationship (Granger and Newbold, 1974). Augmented Dickey-Fuller (1979, 1981) and Philips and Perron, (1988) tests can help avoid false results through stationary test of times series. Our results drawn from stationary tests represented in tables (2) and (3) allow a rejection of the null hypothesis in first difference that signify no stationarity in all our series, but enable an acceptation at a level, that signify integration of the variables at order 1.

|

|

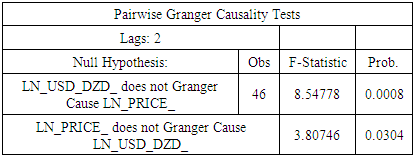

3.3.2. Granger Causality

- In this case, we use Granger causality tests of Clive Granger (1969) for determining whether oil prices is useful in causing the Algerian exchange rate with lagged values of two variables included. Granger causality test reported in table, made it clear that two directional flow at 5% significance.

|

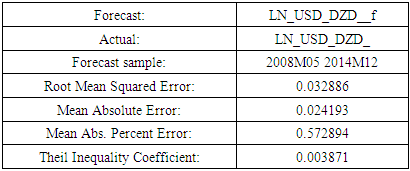

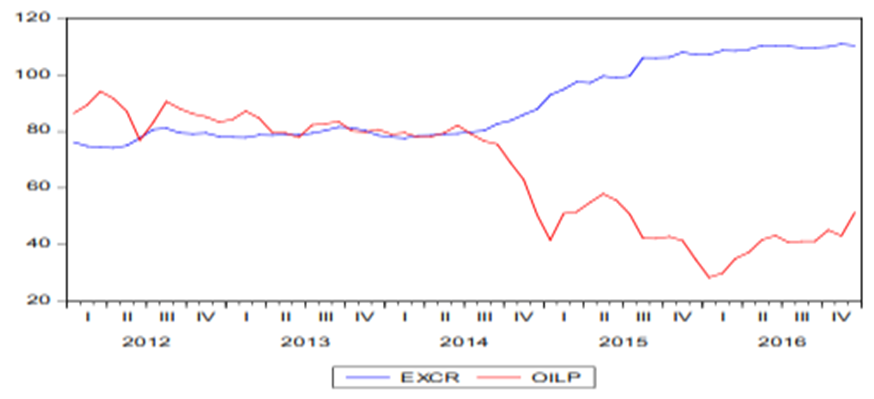

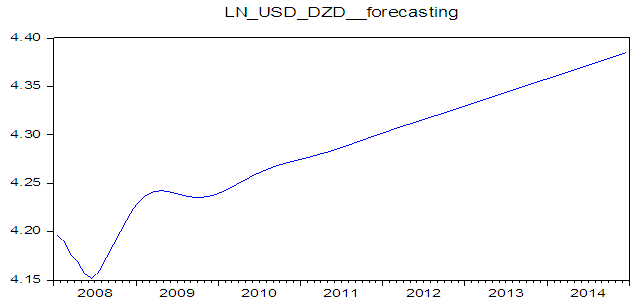

4. Forecasting Exercise

- The final step consist of forecasting the future values of the Algerian exchange rate by using past values of the oil prices for prediction. Usually through a series from M1 2008 to M12 2011 as period estimation and resample the full period (M1 2012) to M1 2015 as out-of sample forecast period.

|

5. Accounting for the Findings

- In the case of Algeria, The main conclusion is that the Algerian exchange rate can be explained by fundamentals complemented with oil price. In fact, high prices of oil generally provoke a large appreciation of exchange rates in oil-exporting countries, but this evidence is not clearly established in the Algerian case, evidenced over the last de level for oil prices to Algerian exchange rate and the reverse. This bidirectional relationship can be clarified how the Algerian Dinar is depend on oil prices change to the effect that the foreign exchange receipts from hydrocarbon exports.Then, we compare forecasts and real the Algerian exchange rate by using Root Mean Squared Error and Theil Inequality Coefficient. The main result is that the Algerian exchange rate can be forecasting by fundamentals complemented with oil price, when change in prices contain information about future movement Algerian exchange rate.

Decade with the non-existence of a co-integration relationship between the Algerian exchange rate and oil price.

Decade with the non-existence of a co-integration relationship between the Algerian exchange rate and oil price.6. Conclusions

- In this paper, we investigated if the oil price in US dollar and nominal exchange rate USD/ Algerian Dinar have a cointegrated relationship in the run long. Our results show that there is a cointegrated relationship. However, the estimation of a VECM model indicates that a 1% increase in oil price would lead the Algerian Dinar to depreciate to 0.25% against US Dollar. Finally, we concluded that change in oil prices contain information about future movement Algerian exchange rate. Furthermore, the Algerian government should care more about economic activities diversification in order to reduce the dependence on oil and gas sector, as well as rent seeking activities, especially with the appearance of alternative forms of energy (such as wind, water, and solar power) and should give importance to shocks on oil prices, while formulating their own exchange rate policy. However, policy attention should be directed to containing market power and, to be more effective, should cover all suppliers (importers, wholesalers and retailers). Moreover, adoption of productive technology in the local market is recommended to benefit from low price oil products, and thus achieve higher surplus in balance of payments through imports reduction.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML