-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2017; 7(6): 274-282

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20170706.02

The Influence of Attitude, Subjective Norms and Perceived Behavior Control on Entrepreneurial Intentions: Case of Algerian Students

Benachenhou Sidi Mohammed1, Arzi Fethi2, Omar Belkhir Djaoued2

1Faculty of Economic Sciences, Abou Bekr Belkaid University, Tlemcen, Algeria

2Faculty of Economic Sciences, Dr. Moulay Tahar University, Saida, Algeria

Correspondence to: Benachenhou Sidi Mohammed, Faculty of Economic Sciences, Abou Bekr Belkaid University, Tlemcen, Algeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of this paper is to examine the main predictors of students' behavioral intentions on entrepreneurship. Theoretically, this research is based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). According to the model of this theory, entrepreneurial intentions are affected by three main factors: Attitudes toward Behavior; Social Norms, and Perceived Behavioral Control. Empirical analysis has been carried out on a sample of 175 students from the University of Tlemcen (in western Algeria). To test our hypotheses, we have used structural equation modeling. The findings of this study have shown that students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship and subjective norms, have a significant effect on behavioral intentions to entrepreneurship. On the other hand, perceived behavioral control had no significant effect.

Keywords: Attitudes toward Behavior, Social Norms and Perceived Behavioral Control, Entrepreneurial Intentions and Structural Equation Modeling

Cite this paper: Benachenhou Sidi Mohammed, Arzi Fethi, Omar Belkhir Djaoued, The Influence of Attitude, Subjective Norms and Perceived Behavior Control on Entrepreneurial Intentions: Case of Algerian Students, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 7 No. 6, 2017, pp. 274-282. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20170706.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Entrepreneurship is an important vocational option. Individual work preferences are increasingly favoring self-reliance and self-direction [10, 29, 45]. On the macro-level, econometric research shows that new and small businesses contribute significantly to job creation, innovation and economic growth [20, 45]. In Algeria, like many countries all over the world, the entrepreneurship is establishing nowadays an inevitable lever for the development and the strengthening of the economic landscape. In terms of economic policies, several actions were led by the Algerian state to encourage the entrepreneurial initiatives especially the ones driven by the youngsters with a university degree. A number of institutions and plans intended to support new business start-ups were created to this end to try to contain unemployment and to create jobs. However, during the last decade, the new business start-ups in several sectors seem to show a downward trend, going consequently, against strategic objectives. Considering this negative observation, the researcher did not remain indifferent and began to wonder about the factors that condition the creation of companies among youngsters with a university degree. In order to identify the main determining factors of entrepreneurial activity, a number of studies were done in Algeria, such as studies conducted by Benhabib (2000); Tabet (2006); Assala (2007), Benredjem (2009), Benhabib et al., (2014a, 2014b), Benachenhou et Boucif, (2016, 2017) to discover the reasons that led small and medium-sized enterprises to failure. The results of these researches concluded that the entrepreneurship should not limit itself to the financial aspect or to the Business plan, but should also consider the study of the entrepreneurial behavior. In this context, a personal analysis of the behavior of the potential entrepreneur can widely overcome the obstacles and assure the success of the project of creating a new firm. The entrepreneurial intention has been considered as the key element to understanding the new-firm creation process [17, 39]. Since the early nineties, an increasing number of contributions employ entrepreneurial intention models [32, 34, 35], confirming the applicability of the concept in different settings [eg: 7, 39, 48, 40]. Several researchers have pointed out that the decision to become an entrepreneur is a complex one, and it is the result of intricate mental processes. In this sense, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) developed by Ajzen (1985, 1991) has been frequently applied to explain this mental process leading to firm creation [38].This research is based on psycho-social models of intent, such as Ajzen's theory of planned behavior (1991). The exploitation of these works in entrepreneurship by a certain number of authors confirms their usefulness in our context, especially since some research is specific to the Algerian context [14, 15] and others to the student populations [11, 12]. According to Boisson et al., (2009), several authors have applied models of intentions that specifically concern the student population such as the Kolvereid study (1996) carried out on 128 Norwegian students in business schools; Autio et al., (1997) tested 1956 Scandinavian, American and Asian students in science; Tkachev and Krueger (1998) carried out a study on a sample of 567 Russian students; the study by Krueger et al., (2000) of 97 former business school students in USA facing a career choice at the time of the study; Audet, (2001) on a sample of 150 third-year business students from Concordia University; the study by Kennedy et al., (2003), carried out among 1075 Australian students. The study of Tounès (2003), carried out among 178 management students, following a predominantly entrepreneurial course (Bac + 5). We are particularly interested in the results of these studies. The use of this model nevertheless remains useful to probe the student's minds in order to identify at what levels there may be possible obstacles to the entrepreneurial spirit. It is in this sense that we use it.The purposes of this study were to describe the nature of the individuals 'attitudes, subjective norms and perceived control associated with their intentions to entrepreneurship, and to determine the extent to which personal attitudes, subjective norms, and perceptions of behavioral control influence students' intentions to entrepreneurship. In order to understand entrepreneurial intentions, it is necessary to understand first the main factors that drive students to start a business.The orientations given on this subject are based on a survey of 175 students at the University of Tlemcen, in western Algeria. Theoretically, the article relies on the model of intention proposed by the theory of planned behavior. The intention to create a business by an individual is assumed to depend on three elements: The perceived attractiveness of starting a business (attitude); the degree of incentive to undertake (perceived what?) in his social environment (subjective norms); the trust he has in his ability to carry out the process to start a business (perceived control over the intention). The evaluation of the various factors impact, evoked by the theoretical framework, can only be done through the use of appropriate econometric modeling of this phenomenon, qualitative, namely structural equations modeling. The results presented are derived from both factor analyses and multiple linear regressions. The theoretical framework and the method are first defined, then, the presentation of the results and their interpretations are discussed.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Entrepreneurial Intentions

- Ernst (2011) suggests that the notion of intentionality dates back to Socrates, who studied why people intend evil behavior [36]. In general, intentions represent a belief that an individual will perform a certain behavior [35]. Regarding the realm of entrepreneurial intentions specifically, there are numerous definitions [5, 43]. Thompson (2009) who analysed various options and came to the conclusion that entrepreneurial intentions can most practicably and appropriately be defined as « a conscious awareness and conviction by an individual that they intend to set up a new business venture and plan to do so in the future » [40]. Entrepreneurial intentions are crucial to this process, forming the first in a series of actions to the organizational founding [16]. Certainly, consistent action cannot be guaranteed. Behavioral intention is the formalization of the intention to try and do something in the future [2, p.132, 23, p.52]. Moreover, intentions toward a behavior can be strong indicators of that behavior [27, 40].

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

- The Theory of Planned Behavior is the most used framework in the category of behavioral models [44, 19]. The main assumptions of the TPB are that intention is a strong predictor of behavior and intention may be assessed by evaluating general attitudes, beliefs, and preferences [19]. The theory of planned action is widely used as the theoretical framework for behavioral studies and has successfully explained a variety of human behaviors and their determinants [28]. The TPB was developed to explain how individual attitudes towards an act, the subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control are antecedents of intentions. Attitude toward behavior (ATB) refers to the degree to which a person has a favorable appraisal of the behavior [7]. Subjective norms (SN) reflect the pressure and approval from significant others on becoming an entrepreneur, thus taking into account the individual's social context [40]. The third antecedent of intention is the degree of perceived behavioral control (PBC). This refers to the perceived ease of performing the behavior and to the perceived control over the outcome of it [2, 7]. Together, the attitude toward the behavior, the subjective norms, and the perception of behavioral control lead to the formation of a behavioral intention, which in turn leads to the performance of the behavior [2]. In particular, authors such as Krueger [35], Kolvereid [32, 33] and Fayolle [25, 24] have used this theory to explain the firm-creation decision [Linan, 2008]. In addition, the TPB has received widespread support as a model to predict intentions and behavior in a range of fields. In a review of 185 studies testing the TPB, Armitage and Conner (2001) found support for the efficacy of the TPB in predicting intentions and behavior across a variety of domains [43].

2.2.1. Attitudes towards Performing the Behavior

- According to Fini et al. (2010) “Attitudes are what we feel about a concept (object of the attitude), which may be a person, a brand, an ideology, or any other entity about which we can attach feeling.” [47]. Krueger (2000) defined this antecedent as the desire of an individual to create new value in existing firms by means of taking entrepreneurial actions or performing an entrepreneurial behavior [47]. An attitude toward the act is defined as “a person's favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior” and is formed by the beliefs about the likely outcomes of the behavior (salient beliefs) and the evaluations of these outcomes [27, 52, 43]. Therefore, people automatically acquire an attitude toward the behavior [52]. The theory of planned behavior postulates that people form favorable attitudes toward behaviors believed to have desirable consequences and negative attitudes toward behaviors associated with undesirable consequences [2]. So the research hypothesis can be formulated as follows:H.1: Attitudes towards behavior have a significant positive effect on Entrepreneurial intentions.

2.2.2. Subjective Norms

- Subjective norms demonstrate the social factors that influence individual. [26, 47].subjective norms incorporate a person's beliefs about the extent to which significant others think the person should engage in the behavior or not [31, 53]. In the case of subjective norms, normative beliefs constitute their underlying determinants. Normative beliefs are concerned with the likelihood that important referent individuals or groups approve or disapprove of performing a given behavior [2, 52]. Included would be the individual's family expectations about the desirability of becoming a lawyer, doctor, or entrepreneur. These normative beliefs are weighted by the strength of the motivation to comply with them [35]. Subjective norms are presumed to judge the social pressures on individuals to perform or not to perform a particular behavior [31, 53]. In general, this type of norms tends to contribute more weakly on intention [5] for individuals with a strong internal locus of control [3, 38] than for those with a strong action orientation [8, 38]. Empirically, we must identify the most important social influences [eg: parents, significant other, and friends]. Therefore, the hypothesis can be formulated as:H.2: Subjective Norms has a significantly positive effect on Entrepreneurial intentions.

2.2.3. Perceived Behavioral Control

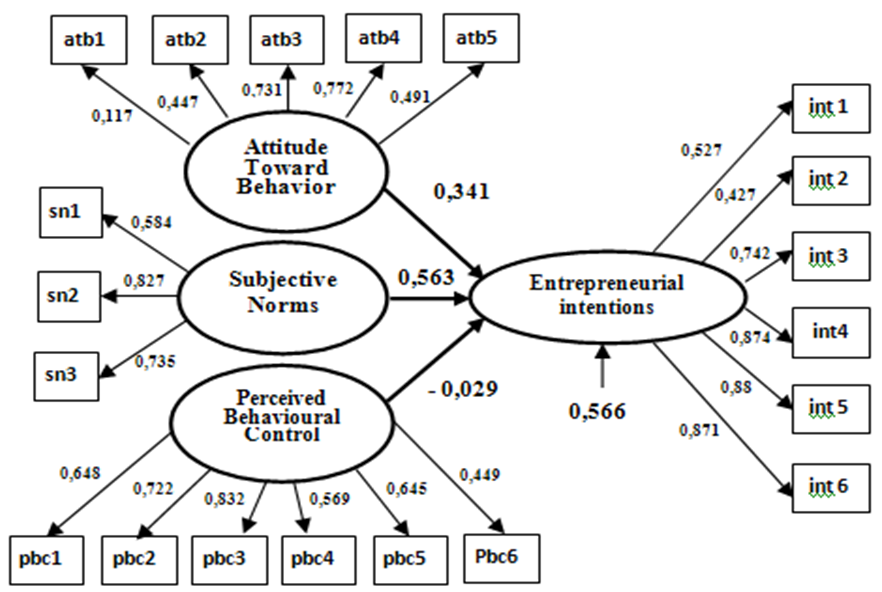

- The third predictor of intention in TPB that is perceived behavioral control is the persons' perceptions of their ability to carry out certain behavior determined by an individual's perception of ease or difficulty in performing the behavior [2, 53]. The importance of this variable in the new-firm creation process resides in its predictive capacity, as it reflects the perception that the individual will be able to control that behavior [3, 38]. Entrepreneurial intentions can also be influenced by self-efficacy factors [21, 37]. Self-efficacy is a person's judgment of his/her ability to execute a targeted behavior [1, 37]. This self-efficacy or perceived behavioral control refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior and it is assumed to reflect past experience as well as anticipated impediment and obstacles [4]. Bandura (1986) notes that the mechanisms for influencing efficacy judgments include ‘enactive mastery' hands-on experience, vicarious learning, and physiological/ emotional arousal [35]. Lee et al., (2011) suggests that Prior studies have identified self-efficacy as a key contributor to entrepreneurial intentions, either directly or indirectly through influencing perceived feasibility [34, 35]. Numerous studies have shown that taking into account perceived behavioral control can indeed improve prediction in behavior. Although conceptually perceived control is expected to moderate the intention-behavior relation, in practice, most investigators have looked at the additive effects of intention and perceptions of control [4]. Therefore, the hypothesis can be formulated as:H.3: Perceived behavioral control has a significant positive effect on Entrepreneurial intentions.In this study, according to Ajzen's TPB the proposed model consists of four dimensions: attitudes toward entrepreneurship (behavioral beliefs and outcome evaluation), subjective norm (Parents, friend, colleague…), perceived behavioral control (knowledge, self-efficacy and resources), they were conceptualized as directly related to their intention to create a new firm. (See. Figure 1). Academic experts in the field of business reviewed the appropriateness of the measurement items, and thirteen items were chosen to capture the three latent constructs.

| Figure 1. Conceptual model and results of SEM analysis |

3. Materials and Methods

- A questionnaire was developed to be used in the data collection process. The measurement items for ATB, SN, and PBC were adapted from previous studies [7, 38, 10]. A total of 175 questionnaires were randomly distributed to respondents comprising students from the faculty of economics, University of Tlemcen. The data were then analyzed using SPSS.22 and Satatistica.08. Descriptive analysis, reliability analysis, factor analysis and regression analysis were then performed on the data.

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

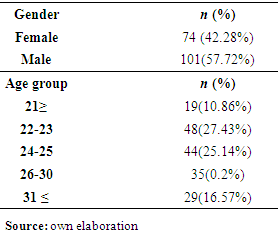

- The empirical analysis has been carried out on a sample of last-year university students. In particular, recent research has found that young university graduates (25-34 years) show the highest propensity towards starting up a firm [38]. A pilot study was carried out with a convenience sample of 175 university students to test and further refine the research instrument. The main survey was fielded in the faculty of economics of Tlemcen University (in western Algeria) from January 2017, with two well-trained students administering the survey to a sample of University Students. More than 200 questionnaires were distributed, out of which 175 (87.5%) were usable. The proportion of males (n1=101, 57.72%) was higher than that of females (n2=74, 42.28%). More than a half of the respondents (n=92, 52.87%) were 22-25 years old, while 20 percent were 26-30 years old (n=35), 16.57 percent were more than 30 years old (n=29), and 10.86 percent were less than 22 years old (n=19). A large portion of the sample follows his / her studies in economics (n=167, 95.42%), while 4.58 percent of the respondents held they are not (n=9). The background of the respondents is presented in Table.1.

|

3.2. Measures

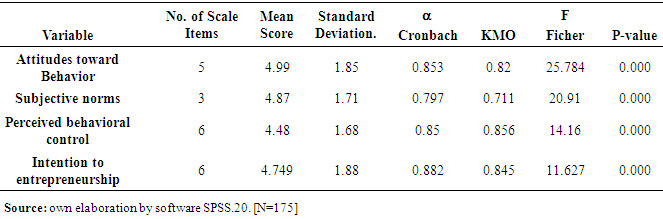

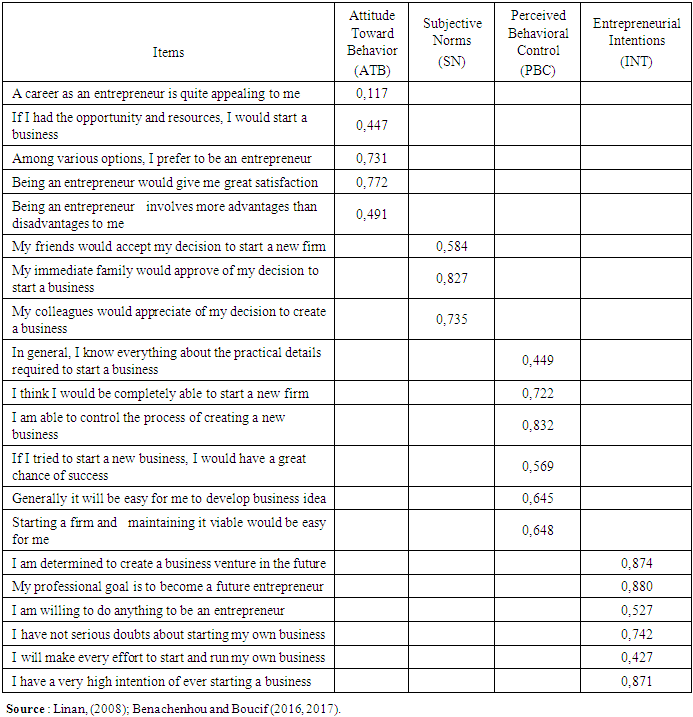

- Four variables from a survey were used for this research. A questionnaire was developed to measure the constructs in the TPB, following Ajzen's guidelines for constructing a TPB questionnaire. Two experts in the field of social psychology and entrepreneurship reviewed the questionnaire for content validity. Based on the pilot study and expert opinions, some changes were made to the questionnaire to increase the clarity of the items. All measures used a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).Table 2 lists the variables, the number of final scale items, mean scores, and measures of reliability of each scale in the present study. The first variable -Attitudes towards Entrepreneurship-were measured by their beliefs and evaluation of performing the behavior. The construct statements used in the present study are listed in Table 3. Each individual's attitude score was calculated by the sum of the five items on the attitude scale. The value of this construct ranges from 1 (small) to 7 (strong). A higher score indicated a more positive attitude towards entrepreneurship. The second variable -Subjective Norms- was measured by the students' normative beliefs in performing entrepreneurship while taking into consideration the expectations of their significant others (such as immediate family or a friend or colleague), and their motivation to comply with the expectations of their significant others. There were three items in the subjective norms scale. The third variable -Perceived Behavioral Control (self-efficacy) indicating students' perception of how easy or difficult it would be to create a new firm was measured using sex scales.

|

|

4. Result

4.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

- Next factor analysis was performed to reduce the number of items into a more (parsimonious/what do you mean) factor. From the factor analysis, four factors were extracted; attitude toward behavior, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention. All items loaded good into each of the factors. As such no items need to be deleted. Each factor items were tested for their reliabilities. Table 2 presents the result of the reliability analysis. The reliability test was run in order to ensure consistency and reproducibility of the instrument. Nunnally (1978) suggests that for any research at its early stage, a reliability score or alpha that is 0.60 or above is sufficient [31]. The Cronbach's alpha for each construct of this study is between0.797 and 0.882 demonstrate good reliability because the construct displayed excellent viability of scales.Then the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Batlett's Test of Sphericity present in Table 2, indicates that the data were appropriate for factor analysis. According to Kaiser (2007), KMO value between 0.8 and 0.89 are considered as meritorious and between 0.7 and 0.79 as middling. The result shows that KMO value between 0.69 and 0.856, and Bartlett's test is significant at less than 0.05 indicates that the data is appropriate for factor analysis. Furthermore, the fisher test is also significant (p<0. 05) indicate the validity of the construct. The associated significance level for sphericity on the basis of a Chi-squared was very small (0.000).On the other hand, According to Fornell and Larcker, (1981) percentage of explained variance should not be less than the recommended level of 50 percent, on this basis, we can see in Table 2, that the value of this index exceeded the minimum acceptance, where the value was between 57.758 % and 71.143%. Table 3 shows the results of convergent validity that was assessed using the Lamda value (λ), which was in terms of 0.5. Therefore, this loading demonstrates the convergent validity of the measurement items, because all indicators have significant loadings on the respective latent constructs (T>1.96, p< 0.05) with Lamda values varying from 0,449 to 0,827 except the value of the first variable of the attitude (atb1=0.117) that were low.

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling

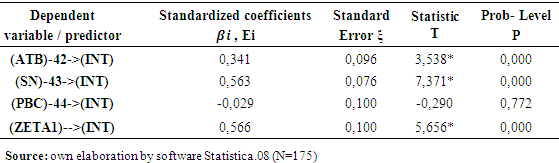

- To evaluate the measurement and structural model, the data were analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling. This method is suitable for this study because the objective of this research is to test the causal relationship between the predictor variables intention and also to investigate the extent to which predictor variables influence students' behavioral intention. The proposed model was evaluated and demonstrated an average model fit.The Chi-square statistic was significant [Chi_square = 362,706, df =167, p=0.000, Chi square /df = 1.95] and six other fit indices [GFI, AGFI; Indice Gamma Population; Indice Gamma Ajusté Population; Bentler Comparative Fit Index; Bollen's Delta] also indicate an average fit, [close to 0.9] which indicate moderately fit for data. Based on Figure 1, there were 23 path coefficients in the structural model. From the 6 path coefficients of the latent variable (PBC), there was one path coefficient, which was not significant and have negative relationship direction (perceived behavior control -> behavior intention) [β3 = -0,029, T<1.96, p >0.05].

5. Findings and Discussion

- As hypothesized, the present study supported that the key constructs of Ajzen's TPB contribute to predicting students' intentions to entrepreneurship. Students' intentions to entrepreneurship was predicted by their attitudes toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control. In addition, the analysis of the present study confirms many previous findings in the literature. The results of all hypothesis testing can be seen as reported in table 4. In regard to testing our stated hypotheses, the First hypothesis stated that there is a positive relationship between students' attitudes towards behavior and entrepreneurial intentions [β1=+0,341; T=3,538>1.96; p < 0.05]. This prediction was supported. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies examining the positive relationship between students' attitudes and entrepreneurial intention [32, 7, 50, 51, 17]. The Second, hypothesis testing indicates that the subjective norms such as family influence, friends support, and colleagues encouragement have a positive influence on students' entrepreneurial intentions [β2=+0,563; T=7,371>1.96; p < 0.05]. Hence, the subjective norms as encouragement from the outside and will affect the intention to create a new firm. This result supports prior studies such as Kolveired, (1995); Autio et al., (2001); Tounes, (2003; 2006), Boissin et al., (2009); Touab, (2014) and Mamoudi et al., (2014). However, a number of studies revealed that the subjective norms have no influence on the student's entrepreneurial intentions [Krueger et al., 2000; Emin, 2003]. Hypothesis 3, stated that there is a positive relationship between PBC and student behavior intention to entrepreneurship. These findings streng then Ajzen (2002) opinion that perceived behavioral control influences intentions. The regression path for the PBC-behavior intention was not significant and have negative relationship direction [β3 = -0,029, T<1.96, p >0.05].

|

6. Conclusions

- The theory of planned behavior (TPB) was chosen as the conceptual framework for this study because it has been used successfully to understand entrepreneurial intention. The study findings supported the TPB proposal that students' positive attitude and subjective norms enhanced their positive intention to create a new firm, but this theory has not been confirmed in regard to the effect of perceived behavior control on students' entrepreneurial intention. Regression analysis revealed that self-efficacy was not a significant predictor of students' intention or entrepreneurial behavior. On the other hand, before conducting the field study on the models of intention, we had to investigate the determinants of firm-creation by students. The various questions posed to students who do not wish to establish a firm may have been the reason why the third hypothesis, which suggests that there is a significant effect on the realization of behavior control, is not valid for student’s entrepreneurial intention. On this basis, this result can not be generalized to all members of society. In addition, the study findings that it was very possible to offer entrepreneurship courses since they develop the students' attitude and intention and the necessary abilities to be an entrepreneur and that it can succeed in the future. We should also note that all favorable conditions must be provided to facilitate the transition from the intention to the conduct of entrepreneurship among university students through structural support (access to financing) and university (course, training and sensitization) in the field of entrepreneurship. Finally, the study concludes that the respondents had complete knowledge on both readily available opportunities to start the businesses, but their perception of entrepreneurial control (self-efficacy) and the possibility of success were negative.

7. Limitations and Recommendations

- Certain limitations dictate caution in the generalization of these findings. First, in contrast to the TPB, the direct path from perceived behavior control to intention behavior suggests that students ' intentions did not fully relate to perceived behavior control. Further research is needed to clarify the direct or indirect path among main constructs, intention, and behaviors in the TPB. Second, the major weakness of this study was that other important variables influencing student’s entrepreneurial intentions might be included in the TPB such as entrepreneurial skills. Third, Future research can take into account individual variables (personality, beliefs, risk-taking, motivations, ...), environmental variables (culture, social networks, reference groups ...), and socio-demographic variables (age, sex, Social class, ...) and other variables that will help us to better understand the entrepreneurial intention in the Algerian context. Fourth, this study has assessed the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Algeria applying the theory of planned behavior (TPB). To this end, therefore, a further research may be useful to specifically examine which entrepreneurial experiences build self-efficacy in a university set up. Fifth, data for this study were obtained from a sample of only one public university in Algeria (Tlemcen University). If all the universities in Algeria were examined, the result could have been generalized.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML