-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2017; 7(5): 230-239

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20170705.04

Farmer Choice, Cost of Transaction, Bargaining Power and Market Information Services in Togo

Koffi Yovo

Department of Agricultural Economic, Agricultural School, University of Lome, Lome, Togo

Correspondence to: Koffi Yovo, Department of Agricultural Economic, Agricultural School, University of Lome, Lome, Togo.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper assesses the effect of the dissemination of prices’ information on the choice of the mode of transaction, the cost of transaction and the bargaining power of maize producers in southern Togo, the maize being the main stuff food among cereals marketed in Togo. To this end, a survey was carried out among maize producers in southern Togo and a selection bias corrections based on the Multinomial Logit Model according to McFadden (1984) approach was performed. The results highlight the fact that despite the dissemination of prices by MIS, the choice of a mode of transaction still depends on the farmers’ informal network. Moreover, the study finds out that dissemination on prices’ information did not neither increase distance trade nor reduce the cost of transaction of the maize producers. However, it improved the producers bargaining power. We found that farmers who are the regular users of MIS received significantly higher prices of maize about 14% more than what received the producers who were not regular users of MIS. Even though the overall effect is mitigated, the results suggested that the market information services are not useless. They need to be improved so as to give satisfaction to the users.

Keywords: Farmer Choice, Cost of transaction, Bargaining power, Market Information System

Cite this paper: Koffi Yovo, Farmer Choice, Cost of Transaction, Bargaining Power and Market Information Services in Togo, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 230-239. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20170705.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The importance of information for the effective functioning of markets has been a central concern of economic theory, since the seminal work of Stigler (1961). Despite this importance, it is surprising that there are so few empirical studies concerning the role of information, in particular, in agricultural marketing systems of developing countries. In other words, we know little about what the impact of improving access to market information is on farmers’ choice of what to produce, how much to sell, where to sell, and the prices farmers receive for their output.In general, three arguments are mobilized to explain the lack of effectiveness of agricultural marketing systems in developing countries: the lack of information, the asymmetric of information and the dispersion of information (Courtois and Subervie, 2015; Galtier and al, 2014; Stiglitz, 1991, Bardhan, 1989). Lack of information about market prices is a key determinant of market transaction. In describing the problems of transactions related to the lack and asymmetry of information in many Sub-Saharan African countries, Courtois and Subervie (2015) point out that farmers typically have a choice between selling their products to traders who travel back-and-forth between villages and markets or transporting their products themselves to the nearest market pick-up in village markets or transporting their products themselves to the nearest market. Many farmers opt for trader pick-up, despite the fact that traders may take advantage of a farmer's ignorance of the market price, seeking to extract a rent from them by offering very low prices for their products. Yet, farmers usually lack information about current market prices because of villages' remoteness and poor communications with marketplaces. When analyzing the role of transaction costs in the farmer's decision to sell to the trader rather than at the market, Fafchamps and Hill (2005) assume that the farmer must choose between receiving a lower price at the farm gate and receiving a higher price at the market yet incurring a transaction cost. The fact is that the farmer does not have the necessary price information to engage in optimal trade or arbitrage.Among the regulatory instruments which improve the process of arbitrage, providing information on the conditions of supply and demand, especially on the evolution of products prices is crucial. This justified the creation in 2008 of the markets information system (MIS) entrusted in collecting and disseminating weekly cereals prices by radio and television. The availability of information allows producers, traders and consumers to rationalize their buying and selling decisions.Market information system can affect profitability the farmers by leading them to change their production, investment, and marketing decisions: they may choose to sell their product in urban markets, sell in larger quantities, farm land more intensively, invest in productive assets, adopt new agricultural technologies, move land out of non-agricultural use, switch crops, or engage in spatial arbitrage (Jensen, 2010).This paper examine the effect of price information dissemination on the choice of transaction’s mode, the cost of transaction and the bargaining power of maize producers in Togo, maize being the main food stuff among cereals marketed in Togo. More precisely, the article tries to answer the following questions: did the weekly dissemination of information on the cereals’ prices enable farmers to develop distant trade, reduce transaction cost and improve bargaining power of maize producers in southern Togo? Yovo (2015) had already assessed the impact of price dissemination on maize markets integration in Togo. Thus, the present paper is an extension of the former and examines the prices’ dissemination on the efficiency of the farmers’ transactions. The remainder of the article is organised as follows: section 2 presents literature review on the role of information in the functioning of the market, the potential impact of information diffusion and some studies on the impact of information dissemination on markets transaction. Section 3 presents the methodology and data used in the analysis. Section 4 presents and discusses the results. Finally the section 5 draws a conclusion and provides a policy implication aiming to improve the functioning of the market information system in Togo.

2. Literature Review

- The modern economic theory places information in the center of the performance of the markets. In the theory of the competitive walrasian general equilibrium, information concerning the scarcity of the resources is available to all the economic agents. This facilitates the optimal allocation of the resources. Thus, the price summarizes information. A high price indicates too short supply or too long demand, and vice versa. In other words, the equilibrium price transmits information to the economic agents and plays to some extent the part in signals of the market (Grossman and Stiglitz, 1976). According to Fama (1970), a market is “informationally efficient” if prices at each moment incorporate all available information about future values. Informational efficiency is a natural consequence of competition, relatively free entry, and low costs of information. If there is a signal, not incorporated in market prices, that future values will be high, competitive traders will buy on that signal. In doing so, they bid the price up, until it fully reflects the information in the signal. Hayek [1945] emphasized that in a market economy, price enables the efficient coordination of large numbers of consumers and producers, each acting only in self-interest and only with information about their own preferences, technology and constraints. Price differentials across markets in excess of transportation costs for example serve as signals to profit seeking agents to re-allocate goods towards the higher priced market. In doing so, they also increase aggregate welfare. However, optimal arbitrage requires agents have full information on prices. Stigler (1961) suggested that such information is rarely perfect, noting that, "Price dispersion is a manifestation - and, indeed, it is the measure – of ignorance in the market.” The possibility of welfare-enhancing arbitrage has been the emphasis in much of the literature on MIS and market performance. This follows primarily from the large empirical literature documenting a lack of spatial integration among agricultural product markets in many developing countries (Yovo, 2015; Bizimana, Bessler and Angerer, 2013).The empirical literature that deals with the impact of MIS or ICT on economic development in poor countries can be divided into two categories. The papers of the first category analyze how MIS improves spatial integration (global coordination) and the second category, the efficiency of transaction (bilateral coordination).In the first category, we can mention three papers: Yovo (2015); Bizimana and al (2013) and Bassolet and Lutz (1998). Yovo (2015) used autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) to assess the impact of price dissemination by MIS on the spatial integration of maize markets in Togo. To this end, the weekly retail maize prices collected from 13 markets for the period without service (2003-2007) and the period with service (2008-2012) were considered. The results show that the impact of price dissemination on the spatial integration of maize markets is mitigated. By reference to Lome, neither rural markets nor northern markets have significantly improved their level of long-term and short-term spatial integration.In the same vein, Bizimana and al (2013), the author analyze the impact of a newly introduced market information system “E-Soko”, on beans markets integration by comparing the period before and after the system was implemented in Rwanda. Beans, both bush and climbing, are the most important traded crop in rural areas of Rwanda, and third most important in urban areas in terms of value. Bi-weekly prices on beans were analyzed for the two time periods: one before the introduction of the market information system “E-Soko” (1999 to 2003) and another one after “E-Soko” was introduced (2007-2012) on eight markets across Rwanda for each period. Vector autregression methods were used to analyze the data and assess the level of market integration in both periods. Stationarity tests show that the price series in the period after the introduction of E-Soko (2007-2012) are all (except one) stationary, which raises the question of the market efficiency. Prices in the period before E-Soko (1999-2003) indicate a good level of integration with Musanze market leading the group. No clear conclusions were drawn from this study regarding the impact of the E-Soko market information system.As concerns Bassolet and Lutz (1998), using ARDL, they did not find a significant effect of the information system on the integration of sorghum markets in Burkina Faso. The authors showed that the prices issued by the information service were not determinant for the arbitrage of cereals traders. According to the authors’ opinion, this is due to the quasi-general ignorance about the day of price diffusion on the radio.The second category of papers, more numerous, comprised studies which assessed the impact of MIS on transaction similar to our research question.Among these, the most cited study on the topic is Jensen (2007). Jensen studies fisheries in India, where fishermen at sea are unable to observe prices in coastal markets. Fishermen sell their catch almost exclusively in their local market due to high transportation costs and non-existent storage capacity. This induces price gaps across markets in excess of transportation costs, resulting in an inefficient welfare state since fish supply varies across markets. The author shows that the introduction of mobile phone service between 1997 and 2001 led to a considerable reduction in fish market price dispersion, the complete elimination of waste, and near-perfect adherence to the Law of One Price. Abraham (2007) reached to the similar outcomes by studying on the same issue in the same area.Aker (2009) using a theoretical model of sequential search and a market and trader dataset that combines data on prices, transport costs, rainfall and grain production with cell phone access and trader behaviour, provided evidence that cell phones reduce grain price dispersion across markets by a minimum of 6.4 percent and reduce intra-annual price variation by 12 percent. Cell phones have a greater impact on price dispersion for market pairs that are farther away, and for those with lower road quality. This effect becomes larger as a higher percentage of markets have cell phone coverage. The specific effects of MIS on transaction efficiency are scare. Goyal (2010) shows that the introduction of the kiosks leads to 1-3% increase in farmer prices and 33% increase in profit. In this framework, farmers initially sold their soybeans in local wholesale markets to traders who possessed price information across markets, while the farmers did not. This analysis thus highlights the pure market power effect, by which price information increases competition. Svensson and Yanagizawa (2009) address the market power issue more directly by estimating the impact of a radio-based MIS on Ugandan farmers. They show that access to market information strongly improves farmers' bargaining power at the farm gate. Specifically, having access to a radio in districts where the MIS project was launched is associated with a 15 percent higher farm-gate price. Fafchamps and Minten (2012) evaluate the effect of a mobile-based MIS by running a randomized controlled trial to test whether Indian farmers who are MIS users obtain higher prices for their agricultural output, they find a zero impact. However, as the authors underline in their conclusion, larger impacts are possible in other contexts, in particular in less competitive and more segmented markets where farmers sell a substantial share of their produce. Courtois and Subervie (2015) estimate the causal effect of a Market Information System (MIS) working through mobile phone networks on Ghanaian farmers' marketing performances. They found out that farmers who have benefited from the MIS program received significantly higher prices for maize and groundnuts: about 12.7% more for maize and 9.7% more for ground-nuts than what they would have received had they not participated in the MIS program.These latter papers reviewed had almost focused only on the effect of price information disseminated by MIS on the bargaining power between a farmer and a trader. The contribution of our paper is to examine in a joint model, more than the bargaining power, the effect of prices’ dissemination on the choice of the mode and the cost of transaction.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Model

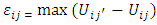

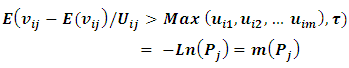

- The model we propose to construct aims to evaluate the effect of the dissemination of price information on the choice of transaction mode, transaction cost and the bargaining power of producers.To sell their produce, maize producers have to choice between four types of transaction: 1) the sale without contract in the village market 2) the sale with contract in the village market 3) the sale without contract in the urban market and 4) the sale with contract in the urban market.According to the logistic approach, the individual makes the choice that maximizes its utility, but the latter is only imperfectly known (Ben-Akiva and Lerman, 1985). Assuming that a producer i has exhaustive alternatives of the mode of transaction to be chosen. The utility he gets when he chooses the alternative j can be represented as:

| (1) |

represents the utility that the individual i derives when choosing the mode j,

represents the utility that the individual i derives when choosing the mode j,  is the vector of the explanatory variables,

is the vector of the explanatory variables,  is the unobserved random component and γ is the vector of the parameters of the model. The utility of the individual i resulting from the choice of a transaction mode j is not observed. Only the transaction mode is observed. Thus, the producer chooses a transaction’s modality j if it provides him with a maximum utility or if he derives the maximum satisfaction from it.

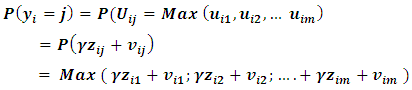

is the unobserved random component and γ is the vector of the parameters of the model. The utility of the individual i resulting from the choice of a transaction mode j is not observed. Only the transaction mode is observed. Thus, the producer chooses a transaction’s modality j if it provides him with a maximum utility or if he derives the maximum satisfaction from it. | (2) |

, this condition is equivalent to:

, this condition is equivalent to: | (3) |

| (4) |

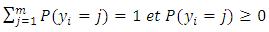

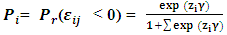

(m being the number of modalities). This probability depends on the value of the utility of the transaction mode compared to the other alternatives. The distribution function of a logistic law takes the following form:

(m being the number of modalities). This probability depends on the value of the utility of the transaction mode compared to the other alternatives. The distribution function of a logistic law takes the following form: | (5) |

| (6) |

the conditional transaction cost when choosing a transaction mode.

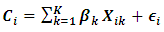

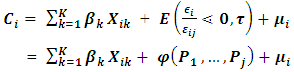

the conditional transaction cost when choosing a transaction mode.  is explained by a number of independent explanatory variables, namely the informational variables (the use or no-use of the MIS). The simplified linear regression model with K explanatory variables is written as:

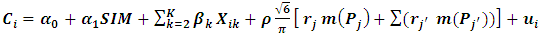

is explained by a number of independent explanatory variables, namely the informational variables (the use or no-use of the MIS). The simplified linear regression model with K explanatory variables is written as: | (7) |

is the explained variable, Xik the set of k explanatory variables, βk the set of variables regression coefficients, and

is the explained variable, Xik the set of k explanatory variables, βk the set of variables regression coefficients, and  is an error term that satisfies

is an error term that satisfies  Since the transaction cost is assumed to condition the choice of the transaction mode, unobservable characteristics affect both the error terms of equations (1) and (7) thus inducing a correlation between the two, i.e.

Since the transaction cost is assumed to condition the choice of the transaction mode, unobservable characteristics affect both the error terms of equations (1) and (7) thus inducing a correlation between the two, i.e.  According to Bourguignon et al. (2007), the generalization of the selection bias correction model is based on the conditional mean of

According to Bourguignon et al. (2007), the generalization of the selection bias correction model is based on the conditional mean of  By expressing,

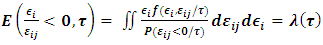

By expressing,

the relation that exists between the different modes of transaction is written:

the relation that exists between the different modes of transaction is written: | (8) |

is the joint conditional density function of

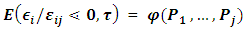

is the joint conditional density function of  Given that the relation between the different modes of transaction and the corresponding probabilities are reversible, there exists a unique function φ which can substitute for λ (τ):

Given that the relation between the different modes of transaction and the corresponding probabilities are reversible, there exists a unique function φ which can substitute for λ (τ): | (9) |

| (10) |

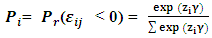

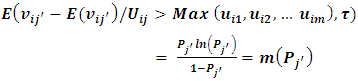

is an error term independent of the regressors. From this general model, there are different approaches to correct the selection bias depending on more or less restrictive hypotheses: two parametric approaches have been defined by Lee (1983) and Dubin and McFadden (1984) and a semi parametric approach By Dahl (2002). According to Bourguignon and al. (2007), the method of Dubin and McFadden (1984) gives better results than those obtained by the method of Lee (1983). These authors show that the selection bias in the equation of interest is appropriately corrected with the Dubin and McFadden (1984) method even in the case where hypothesis IIA is not verified in the choice model. Therefore, for our empirical analysis, we use the Dubin and McFadden method (1984).To construct the selection bias correction term, Dubin and McFadden (1984) give the following hypothesis from the error term

is an error term independent of the regressors. From this general model, there are different approaches to correct the selection bias depending on more or less restrictive hypotheses: two parametric approaches have been defined by Lee (1983) and Dubin and McFadden (1984) and a semi parametric approach By Dahl (2002). According to Bourguignon and al. (2007), the method of Dubin and McFadden (1984) gives better results than those obtained by the method of Lee (1983). These authors show that the selection bias in the equation of interest is appropriately corrected with the Dubin and McFadden (1984) method even in the case where hypothesis IIA is not verified in the choice model. Therefore, for our empirical analysis, we use the Dubin and McFadden method (1984).To construct the selection bias correction term, Dubin and McFadden (1984) give the following hypothesis from the error term  of the choice equation.

of the choice equation. | (11) |

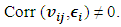

in the total sample, and

in the total sample, and  is the correlation coefficient between

is the correlation coefficient between  With the Logit Multinomial model, we can write:

With the Logit Multinomial model, we can write: | (12) |

| (13) |

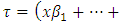

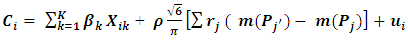

The equation of interest to be estimated can thus be expressed as:

The equation of interest to be estimated can thus be expressed as: | (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

is the transaction cost supported by producer i; MIS is a binary variable taking the value 1 if producer i is a user of the MIS and 0 otherwise;

is the transaction cost supported by producer i; MIS is a binary variable taking the value 1 if producer i is a user of the MIS and 0 otherwise; is the vector of the control variables;

is the vector of the control variables; represents the bias correction term relating to the choice of the mode of transaction j;

represents the bias correction term relating to the choice of the mode of transaction j; represents the bias correction term relating to the choice of the alternative mode of transaction

represents the bias correction term relating to the choice of the alternative mode of transaction

represents the correlation coefficient between the residuals of the choice j equation (1) and the cost equation (7);

represents the correlation coefficient between the residuals of the choice j equation (1) and the cost equation (7); represents the correlation coefficient between the residuals of the alternative choice

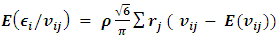

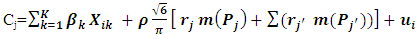

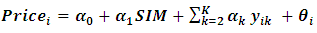

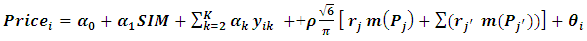

represents the correlation coefficient between the residuals of the alternative choice  equation and the cost equation (7); We can derive the effect of price diffusion on bargaining power by taking inspiration from Svesson and Yanagizawa (2009) and Courtois and Subervie (2015) who define bargaining power as the positive marginal price resulting from the adoption of the MIS. In other words, any increase in the price resulting from the use of the MIS is interpreted as an increase in the bargaining power of the actors. So this effect is captured by substituting Ci in equation (16) by price as expressed in equation (17) below:

equation and the cost equation (7); We can derive the effect of price diffusion on bargaining power by taking inspiration from Svesson and Yanagizawa (2009) and Courtois and Subervie (2015) who define bargaining power as the positive marginal price resulting from the adoption of the MIS. In other words, any increase in the price resulting from the use of the MIS is interpreted as an increase in the bargaining power of the actors. So this effect is captured by substituting Ci in equation (16) by price as expressed in equation (17) below:  | (17) |

| (18) |

represents the correlation coefficient between the residuals of the choice j equation (1) and the price equation (17);

represents the correlation coefficient between the residuals of the choice j equation (1) and the price equation (17);  represents the correlation coefficient between the residuals of the alternative choice

represents the correlation coefficient between the residuals of the alternative choice  equation and the price equation (17).

equation and the price equation (17).3.2. Data and Descriptive Statistics of the Variables

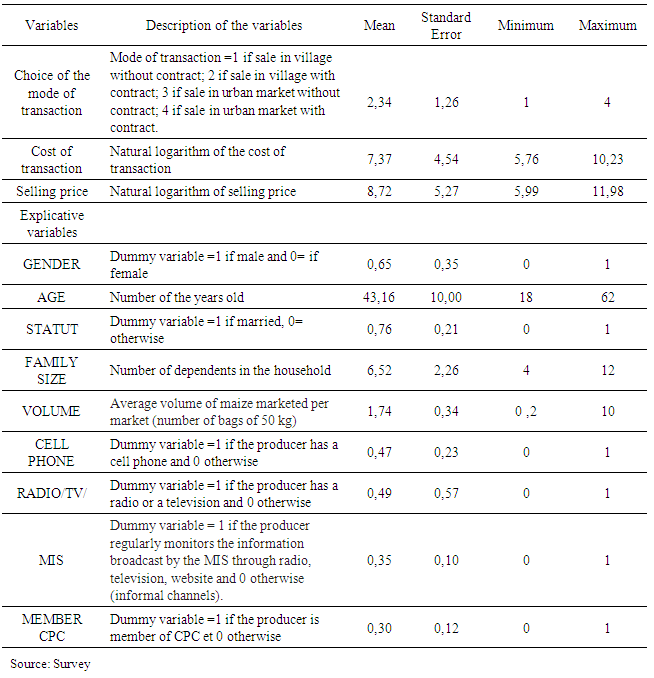

- In total, 350 producers were surveyed in four rural markets: Ahepe, Aassahoun, Agbelouve and Anie and three urban markets: Lome, Tsevie and Atakpame. All producers who came to the market on the day of the survey were surveyed. In case of the refusal or reluctance of a producer, the investigator moves on to another.Table 1 in appendix gives definitions and descriptive statistics of variables related to the models to be estimated. The table shows that 65% of producers are men. The average age of producers is 43 years. They are mostly married with about 7 dependents. Maize production is their main source of income. The average volume marketed during the survey period by a producer is approximately 2 bags and half. 49% of producers have a radio or television and 47% a mobile phone. 35% of the producers regularly monitor the information broadcast by the MIS through radio and television. 30% of producers are members of the Cereals Producers Corporation (CPC).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Selling Prices and the Costs of Transaction

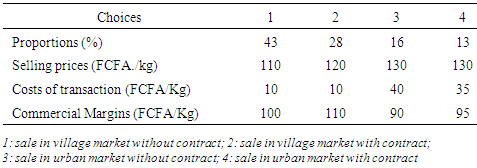

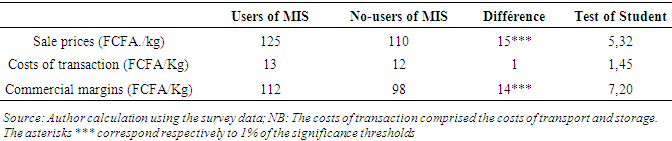

- In order to sell their production, maize producers use four modes of transaction. The proportions of each mode reported in Table 2 (appendix) are as follow: 1) Sale without contract in the village 43%; 2) Sale with contract in the village: 28%; 3) Sale without contract in the urban market: 16% and 4) Sale with contract in the urban market: 13%. It appears that a larger number of producers opted for sale in the village without contract, although the second option is more advantageous financially. In fact, this second mode of transaction has the disadvantage of a deferred payment. Since the producers have a preference for liquidity, the mode of transaction 2 appears less attractive than the mode of transaction 1. It is mainly used by the producers who are members of the cereals corporation. Through their corporation, they organize bundled sales, enabling them to receive better prices with relatively modest transaction costs. However, due to deferred payment, a relatively small number of the members (30%) sell their production through that channel. Options 3 and 4 appear to be the less financially attractive. However, despite the relatively high cost of transport, the producers who are able to achieve economies of scale due to the size of their transaction realize interesting commercial margins.Table 3 (appendix) compares prices and transaction costs between the users and non-users of MIS. The table indicates a significant difference of the selling prices between users and non-users of the MIS. This result suggests that MIS users realize a commercial gain of 15 FCFA / kg, an increase of 14% compared to non-users. As concerns the transaction costs, the table shows no significant difference between users and non-users of the MIS. Besides, the margin of producers using MIS is significantly higher than that of non-users MIS. The commercial gain of 15FCFA / Kg appears statistically significant. This result is close to that found out by Courtois and Subervie (2015) for MIS Esoko in Ghana. Indeed, the authors had showed that the Esoko MIS reinforced the producers' bargaining power for 12.7%.

4.2. Effect of Prices’ Dissemination on the Choice of Producers’ Mode of Transaction, Cost of Transaction and Bargaining Power

- In order to test the idea according to which the dissemination of cereals prices improves the efficiency of transaction, the model of Dubin and McFadden (1984) as specified by Bourguignon al. (2007) enable us to test both the effect of price dissemination on the choice of the type of transaction, the cost of transaction and the farmer bargaining power.

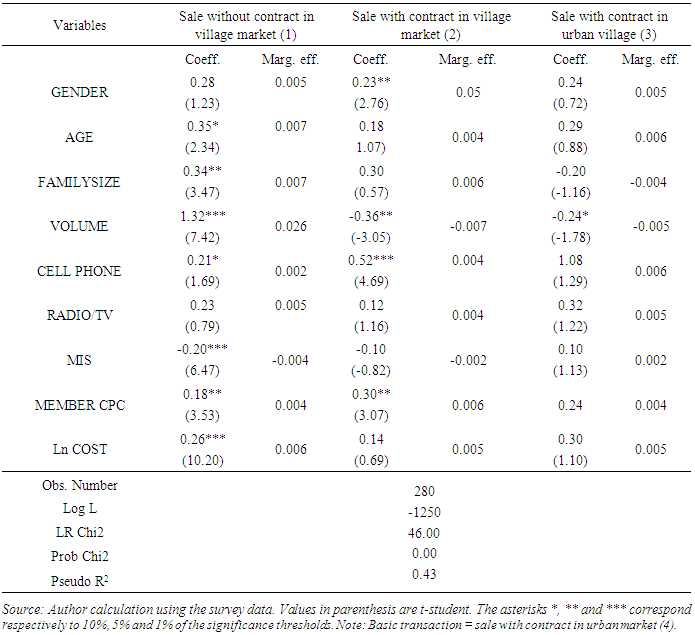

4.2.1. Estimation of the Choice Model: The Multinomial Logit

- Table 4 (appendix) presents the estimation’s results of the Logit Multinomial model under the assumption that the sale with contract in the urban market (mode 4) represents the basic transaction mode. The table shows that the estimated model is globally significant. The explanatory variables explain in a significant proportion the choice of the mode of transaction of the producers. Indeed, statistics of the ratio of Log of likelihood are significant at the threshold of 1%. Similarly, pseudo R2 are at acceptable levels and consistent with the results found in other studies.The analysis of Table 4 (appendix) shows that the first variable of interest, the MIS, has a negative and significant effect on the choice of the mode of transaction 1 and not significant on the modes of transaction 2 and 3. The result seems to indicate the fact that the dissemination of prices information by the MIS did not play a decisive role in the choice of the mode of transaction. The choice of the farmer still depends on the informal network. However, the positive effect of membership of the cereals corporation on the transaction mode 1 and 2 shows that, through information disseminated within producers members of cereals corporation, uninformed producers acquire information and make efficient choices as well as regular MIS users. This result tends to simply highlight the spillover effect of the dissemination of prices by MIS.Moreover, contrary to the expected effect, the diffusion of prices did not encourage the distance trade. This is due to the fact that the sale in the village is financially more profitable than the sale in the urban market in the context of the area under study. It is therefore possible to deduce that the producers were rational and made efficient choices before adopting the MIS. Nevertheless, the effect measured is just a minimal effect due to the fact that the external effects of price dissemination are not taken into account. Indeed, it is reasonable to assume that uninformed producers acquire information from informed producers and make similar choices.

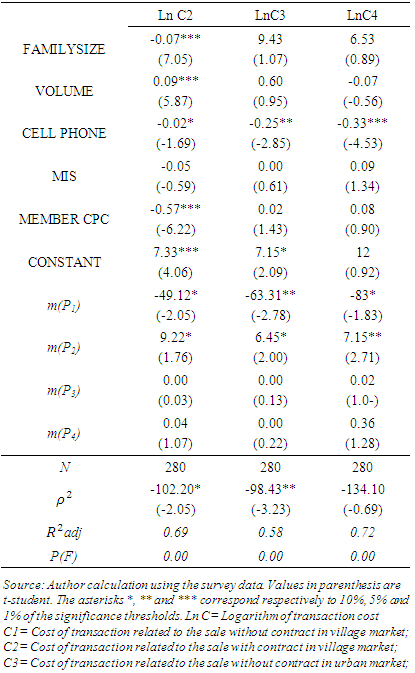

4.2.2. Estimation of Cost Equations

- Table 5 (appendix) presents the results of the regression model estimation. The transaction cost for each individual represents the dependent variable. The first step in the estimation of the choice model according to the Dubin and McFadden (1984) approach, as explained by Bourguignon and al. (2007) enable us to obtain the probabilities of choice and to calculate the correction terms of the selection bias. By following Huesca and Camberos (2010), Ma and Abdulai (2015), these correction terms are then integrated into each cost equation (Equation 16). The correction terms for the four choices of transaction are denoted respectively m1, m2, m3 and m4. Some coefficients associated with the correction term m(Pj) are significantly different from zero, denoting therefore the existence of a selection bias. This result confirms the hypothesis that the estimation of the separated cost equations, without taking into account the endogenous decision of the choice, would have led to biased estimations. Only the number of control variables required was included in the cost equations.The interest variable, the MIS does not seem to directly influence the transaction costs of the different transaction modes. In other words, the dissemination of prices by the MIS does not appear to contribute to the reduction of transaction costs. This result is not counter-intuitive since the dissemination of prices by the MIS has directly little influence on the producers' choice. The results in Table 4 (appendix) indicate that it is other factors which are decisive in minimizing transaction costs. These variables include CELL PHONE, MEMBER CPC, VOLUME and FAMILYSIZE.The mobile phone enables the producer to explore multiple markets and reduces the cost of finding collectors or wholesalers. Membership in the CPC allows the producer to reduce transaction costs through bundling sales. As regards the volume of trade, the big producers sell their produce to collectors / wholesalers under contract at the village level. This strategy not only enables them to minimize transaction costs but also to obtain from the collectors / wholesalers some season credits. As regards the family size, it is interesting to note that the families with many dependents opt to sell their production in village because the dependents are employed to carry the product to the village market reducing the cost of transaction.

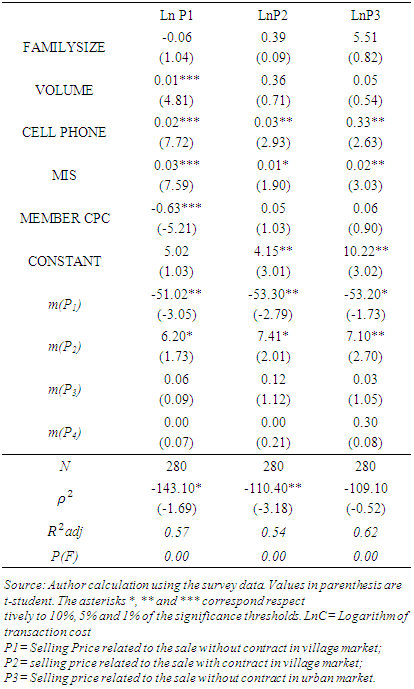

4.2.3. Estimation of Price Equations

- By following Svesson and Yanagizawa (2009) and Courtois and Subervie (2014), it is possible to evaluate the effect of the dissemination of the MIS on the bargaining power of the producers. For this purpose, we regress the informational variables, in particular the MIS variable on price received by producers from the sale of maize. If the marginal price resulting from the use of the MIS is positive, then we conclude that the producer's bargaining power is improved. This leads us to estimate a price equation. We postulate that the choice of a mode j depends on the incentive offered by prices. Thus, the estimation of the price equation for each mode raised a problem of selection bias. To correct this bias, we again resort to the Dubin and McFadden (1984) model as specified by Bourguignon et al. (2007).As before, the first step is the estimation of the choice model. This enables us to obtain the selection probabilities and to calculate the selection bias correction terms. These correction terms are then integrated into each price equation. The correction terms for the four modes of transaction are noted respectively m1, m2, m3 and m4 as before. Some coefficients associated with the correction term m (Pj) are significantly different from zero denoting the existence of a selection bias. This result confirms the hypothesis that the separate estimate of the equations, without taking into account the endogenous decision of the choice, would have led to biased estimation. Only the number of control variables required was included in the price equations. The results of the estimation reported in table 6 in appendix show that, contrary to the above, dissemination of cereals prices by the MIS improves the bargaining power of producers regardless of the mode of transaction. This result is confirmed by CPC membership effect which has induced a spillover effect on the producer bargaining power thanks to the inherent benefit of bundling sale through the producers’ organization. However, mobile phone use seems to have a much stronger effect on the bargaining power of producers.As regards the farmer bargaining power, we can connect this research to other national markets; In fact, the results of this study are in line with what found Courtois and Subervie (2015) who showed that in Ghana, farmers who have benefited from the MIS program received significantly higher prices for maize and groundnuts: about 12.7% more for maize and 9.7% more for groundnuts than what they would have received had they not participated in the MIS program. Our results also corroborate the issue of Svensson and Yanagizawa (2009) who show that access to market information strongly improves Ugandan farmers' bargaining power at the farm gate. Moreover, the result of this paper is not in contradiction with Jensen (2007), Abraham (2007), Goyal (2010) and Aker (2009) who show that in India and Niger, information dissemination create competition which leads to higher prices. These results confirm that the dissemination of information by MIS or ICT is still useful for farmer’s decision-making in developing countries.

5. Conclusion and Implications for Public Policy and Future Research

- The Market Information System (MIS) in Togo collects data on prices for the main agricultural commodities mainly the maize in major markets and disseminates the information through radio and television. The aim of this dissemination is to make the markets more transparent, thus improving the arbitrage of the agents. This paper assesses the effect of the dissemination of prices’ information on the choice of the mode of transaction, the cost of transaction and the bargaining power of maize producers in southern Togo, maize being the main stuff food among cereals marketed in Togo. To this end, a survey was carried out among maize producers in southern Togo and a selection bias corrections based on the Multinomial Logit Model according to McFadden (1984) approach was performed. The results highlight the fact that despite the dissemination of prices by MIS, the choice of a mode of transaction still depends on the farmers’ informal network. Moreover, the study finds out that dissemination on prices’ information did not neither increase distance trade nor reduce the cost of transaction of the maize producers. However, it improved the producers bargaining power. We find that farmers who are the regular users of MIS received significantly higher prices of maize about 14% more than what received the producers who were not regular users of MIS. Even though the overall effect is mitigated, the results suggested that the information service is not useless. It needs to be improved so as to give satisfaction to the users. The paper recommends to make market actors aware of the existence of MIS and to adapt supply to demand for information. One limitation of this research is to not taking into account the external effect of the dissemination of prices information. This has led to the minimal effect of the dissemination. It would be interesting for future research to use for example the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) with difference in Difference (DD) regression approach to correct bias related to the external effect of the dissemination of prices on the farmer bargaining power.

Appendix

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML