-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2017; 7(2): 88-96

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20170702.03

Fertility, Female Labour Force Participation and Part-time Employment of Women: Evidence from OECD Countries

Gülten Dursun, Evren Denktaş

Department of Economics, Kocaeli University, Kocaeli, Turkey

Correspondence to: Gülten Dursun, Department of Economics, Kocaeli University, Kocaeli, Turkey.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In this study we investigated the relationship between female labour force participation rate, part-time employment and total fertility rate in OECD countries from 2000 to 2013. For that aim, we employ panel techniques which panel cointegration, Granger causality and long term structural estimation methods. Correlation between female labour force participation rate and total fertility rate reflects inconsistency between child care and job security. Existence of cointegration between female labour force participation rate and total fertility rate in OECD countries is main finding of this study. Findings show that increase in total fertility rate causes decrease in female labour force participation rate in OECD countries. On the other hand, there are evidences that part time employment provides women easier to have job and inconsistency hypothesis is weaken.

Keywords: Fertility, Female labour force participation, Part-time employment, Panel cointegration

Cite this paper: Gülten Dursun, Evren Denktaş, Fertility, Female Labour Force Participation and Part-time Employment of Women: Evidence from OECD Countries, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2017, pp. 88-96. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20170702.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Rapid changes in socio-economic parameters in twentieth century provide women revolutionary rights and different life style comparing to previous centuries. As their rights equalize with men in all spheres, their roles also change, but these new roles sometimes conflict with their traditional roles. On the one hand, they proceed in their working career, on the other hand, making a child becomes a though decision. While population growth rate was high with the increasing wage and consumption levels, urban fertility rates declined by years in the direct of family preferences. These preferences are formed by some historical occurrences. First, birth control becomes prevalent. Second, women determine their own destiny in their work life day by day. They can choose their jobs, and can promote their responsibilities in their career more specifically. These provide them heavy weight in decision process of their families. But also some negative issues form their preferences. Labour market rigidities, high unemployment rates, weakness or expensiveness of childcare services, opportunity cost for time spent for mother's child care are the some of them that make the birth decision though.Our study is motivated by some experiences proposing that part time employment can play a role in understanding the negative association between fertility and female labour force participation. There are some solution suggestions to increase fertility rate without negative impact on female labour force participation rate including stimulating part-time work among mothers and this paper researches whether part time jobs1 provide some solutions for the problem through panel cointegration, Granger causality and long term structural estimation methods. In this study we investigate the relationship between female labour force participation rate, part-time employment and total fertility rate in 31 OECD countries from 2000 to 2013. A major contribution of our study compared with previous ones is that we add the part-time work dimension in the work environment of the women. This study expands on the limited literature that examines the relationship and causality between female labour force participation rate, part-time employment and fertility in the 31 OECD countries.This study is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews main empirical literature conducted in the areas of female labour force participation rate, part-time employment and fertility. Section 3 describes the data and the empirical specification. Section 4 provides the methodology and empirical findings. Finally, Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature Review

- If part-time job variable is not considered in triple relationship mentioned in this work, we can see that there are a lot of analysis sought cointegration between fertility and female labour force participation. For example, Becker (1960) questioned Malthusian theory which claims that population grows at a rapid rate, unless exceeds the growth of subsistence goods. Because, this claim is not apparent in twentieth century, especially when it comes to urban families. Seemingly, fertility decreases, and when he explains why this diminution at fertility rate occurred, he shows increasing female labour force participation rate and growth in the earning power of women among the reasons. But we must mention that, his main reason for decreasing fertility is that utility maximizing parents get benefit of high educated children so that they maximize expending for education for each children, in other words, they prefer quality to quantity. Another analysis emphasizes on “fertility revolution” sourced from modernization of human personalities consisted of increased openness to new experience, increased independence from parental authority and so on, these all encouraged women to build a career; but above all, give weight to fertility control (Easterlin and Crimmins, 1985). When the child born, mothers emotional tie up to her child is most important reason that to leave her job. When she quits, she would not participate to work force again or she will delay this participation until her child grows up. This situation points role incompatibility hypothesis in which woman find herself two different role as a mother and as an employee (Lehrer and Nerlove, 1986). The causation between female participation rate and total fertility rate doesn’t have to be in one direction (Mishra et al, 2006). We emphasised on impact of total fertility rate on female participation rate above, but opposite direction of causation is also valid and not inconsistent with incompatibility hypothesis. Accordingly, if the rate of women who consider of opportunity cost of having child in an economy is relatively high, then we can say that female labour participation may have negative impact on total fertility rate. Opportunity cost in here involves forgone income, loss of social network and companionship in the work-place and also delayed promotions sourced from interruption in career path of woman. As human capital woman got is high, opportunity cost of having children is also high. Country specific researches give some issues for relationship between market structure, labour market and fertility. In her analysis, Del Boca (2002) emphasises on market rigidities in Italy impact decisions of women about having children. Scarcity of part time works comparing to other developed countries, oblige them to make a preference between full time employment and non-working. Beside the structural problems such as inefficient childcare services; highly regulated labour market has negative impact on fertility in Italy. Women’s fear can be described by two dimensions. First, if they quit, they may not return. Second, even they didn’t work before, they delay to make children so that having many children causes disadvantage to have employed. Hakim (2003) analyses the problem through preference theory. She mentions that demographic researches too much focus on variables such as delayed marriage, high education level when they seek the reasons for diminution of fertility at the cost of avoiding social processes and motivations. On the other hand, preference theory focuses on individuals, their heterogeneity and historical context. In her work, women are classified as “home-cantered”, “work-cantered” and “adaptive”. Home cantered women don’t prefer to work; family and growing children are main priorities for them. They are most fertile ones in the society. In contrast, work-cantered women don’t prefer to make children. They are high educated with high earning profile; and their main priority is their job. Probably, they may have one or two children; but in fact, they are the least fertile individuals. Adaptive women, that their number is about %60 among others, are neither home-cantered nor work-cantered. Their preferences change as necessities do. The ones who transfer from full time to part time jobs when they have children are adaptive women. Hence they give more time for child caring. One can inference from the analysis, rates of these types are determiner of impact of part time job opportunities on fertility rates, as well as part time job rates itself. But also, as Del Boca expressed, existence of part time jobs is related to demand of firms for this kind of work type (Del Boca, 2002).Whether part time jobs are safe port to compensate the losses from child caring or not is also debated. Marco Francesconi (2002) suggests women who are employed in full time jobs unpaid maternity leave rather than part time work. She compares these two types of jobs in her work. Accordingly, education level and full time job experience has a positive effect on full time wages, while there is no substantial effect of part time experience on part time wages. We know that, there is a strong correlation between fertility and earning profile in labour market. One who has comparative advantages, in another saying, high earning profile, then she might have lower marginal utility from having a child. The women who would have higher marginal utility from having a child are the ones who have lower earning profile. Francesconi (2002) gets some other results from her work. For example, as the number of children increases in a family, mother’s probability of working in full time job decreases. Also as the husband’s income rises, woman becomes more reluctant to work in any type of jobs. Mothers who have children at age between 0-6 years prefer to be non-working. On the other hand, when their children grow, they prefer to work in a full time job; but not in part time one. Francesconi (2002)’s calculations through joint dynamic model inferences that women who have maternity leave would get higher life time utility rather than preferring part time working or non-working for a while. Ahn and Mira (2002) research relationship between average total fertility rates and female participation rates in 21 OECD countries from 1970 to 1995 using panel data tests. The survey shows that two variables have negative correlation until late 1980s; then positive correlation throughout 1990s. According to authors the reason of this reversal may be occurred due to developments in market childcare services. As the women’s wages rise, they participate to labour force more, and their demand for childcare services increases. Del Boca et al. (2005) analyzed the relationship between labour supply and fertility in a study of Italy, France and the United Kingdom for the period 1994-2000. Accordingly, part-time work has positive effects on labour force participation rates only in Italy. In Italy, part-time jobs are seen as a temporary solution when looking for better jobs connections. But in Italy, part-time work has a strong negative effect on fertility. Similary, Bratti et al. (2005) investigated the factors associated with female labour force participation after the birth of the first child in Italy. According their findings, several factors related to work are influential on new mothers' participation decisions. Work opportunities, particularly in the public sector or at large firms, are positively associated with labour force participation in the postpartum period. Women with employment protection in particular are encouraged to participate in the workforce immediately after birth. Da Rocha and Fuster (2006) attempted to construct the quantitative theory of fertility and labour market decisions among OECD. The authors examined the role of labour market frictions generating a positive link between fertility and employment. Findings show that labour market frictions are the key to understanding women's fertility behavior in countries where they enter the labour market.Another analysis is on relationship female labour force participation and total fertility rates in OECD countries (Mishra and Smyth, 2010). Separating female groups by age as 15-34 and 15-64, and using panel cointegration and Granger causality tests, Mishra and Smyth (2010) find that these two variables are cointegrated for both two groups. When the analysis is based on the period 1980-2005, there is a causality from female labour force participation rates to total fertility rates. On the other hand, there is a bi-directional causality for the period 1995-2005. Writers comment this situation as “...not only were there career-oriented women less willing to have children, but there was also an increase in family-oriented women having children, that were unable to enter (or re-enter) the workforce because of the factors associated with the role incompatibility hypothesis discussed above”. This comment is consistent with the statements of writers mentioned above. Although results show strong correlation between two variables, the effect of part time jobs is not considered. The relationship between female participation in employment and fertility is depending on the educational level. A study by Ibáñez (2010) proposed both institutional and micro perspective when analyzing different aspects of parenthood decisions in Spain. Ibáñez (2010) show that the probability of being a parenthood of university graduate women’s is very high. In addition, part-time work is an important factor for motherhood, but the results are not clear.Gomes et al. (2012) studied the relation between women’s part-time employment and fertility trends in European countries, using the most recent Eurostat data from 2006 to 2010. In this respect, the authors find that the relationship between fertility and employment is not related to full-time employment, but is a result of part-time employment.Modena et al. (2014) have tried to explain women's low labour force participation rates and low fertility levels in their work for Italy. The authors hypothesize that women's decisions to give birth depend on their level of employment, income and wealth. According to their findings, the instability of the working status of women significantly affects the decision to have the first child. The fact that the households have a low income leads them to delay the attempts to have the first child. The likelihood of further births is significantly affected by household incomes.Blazquez Cuesta and Moral Carcedo (2014) have discussed the transition of labour market between non-employment, part-time and full-time employment among women aged 20-45 living with partner for Denmark, France, Italy, Netherland and Spain. The authors suggest that the responsibility for child care is very effective in this labour marker transformation. Women are withdrawn from labour markets to give birth. Later, women opt for part-time jobs to reconcile work and family life. At that time, they probably spend time with their children in their homes. The authors have found evidence that the part-time employment and non-employment labour market conditions are closely related. Women in part-time employment in year t-1 are not employed the following year. Similarly, women who are not included in employment continue to be out of employment the following year. Moreover, it also prevents career development for women who can work part time and reduces their ability to compete on an equal basis with men.Gehringer and Klasen (2017) have proved that family politics has a steady impact on women's labour force participation in a static and dynamic panel study of women of three age groups in 21 European Union countries during 1998-2007. However, these policies have a greater impact on women's behaviour regarding the type of employment. The authors' results show that higher spending on family allowance, cash benefits and day care supports part-time employment, but that only parental leave is decisive in full-time employment.We can’t avoid that demand of firms and popularity among other economic actors for part time positions distinct from country to country. In 2012, part time employment as a proportion of total employment in Netherlands was over %60; while same indicator was below %10 for Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovak Republic and Bulgaria (OECD, 2014). Part time job is sometimes described as a job in which an employee works less than 30 hours in a week. However, if employees in Finland and Britain work for 30 hours in a week, they are classified as full time workers, while they are classified as part time workers in Sweden (Hakim, 1997). Also there are some part time job types such as “half-time jobs” in which employees work around 15-29 hours in a week and “marginal work” with exemption from income tax and social contributions, involves less than 15 hours in a week.

3. The Data and Model Specifications

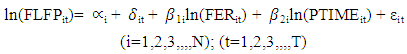

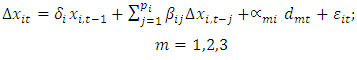

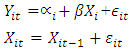

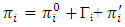

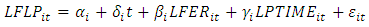

- The study used panel data consisting of 31 cross sections and each cross section cover a time period of 12 years from 2000 to 2012. The countries we consider in this analysis are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Korea, Rep., Luxemburg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Rep., Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, UK, US. The unit of measurement for all the variables is a percentage. This gives 31 x 12 = 372 observations. The data is obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank. The data is not available for different indicators in 31 OECD countries, which in turns limit our ability to use all the data available in different years. In turn, we are forced to reduced our years of observations and choose years that data is available and more balanced. The logarithms of the variables are used in the empirical analyses. EViews Standars Version 8.0 is used for all estimations.The panel cointegration tests are applied to determine the existence of long-run relationship among the variables. In our empirical analysis we use two different types of panel cointegration test. The first of tests was introduced by Pedroni (1999, 2004) and a second type was introduced by Kao (1999) test which is based on the Engle-Granger (1987) two-step (residual-based) procedure. An important property of cointegration is that the variables should be integrated of the same order. For this aim the panel unit root test are applied on the series under consideration to check the order of integration.We consider the following empirical model:

| (1) |

is the intercept term; and

is the intercept term; and  is the slope coefficient with the expected positive sign. We expected the fertility rate to reduce the contribution of women to the labour market. Thus,

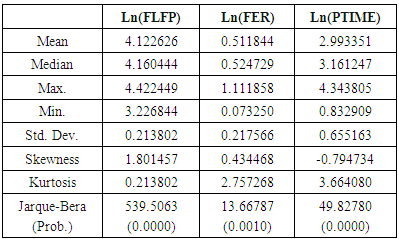

is the slope coefficient with the expected positive sign. We expected the fertility rate to reduce the contribution of women to the labour market. Thus,  is the slope coefficient with the expected negative sign. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

is the slope coefficient with the expected negative sign. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

|

4. Econometric Methods and Findings

- In this study, the relationship among female labour force participation rate, part-time employment and total fertility rate in OECD countries between the years of 2000 – 2013 were analyzed using panel data methods. First, 4 distinct types of panel unit root tests are employed to confirm the nonstationarity of the series in a panel system of the 31 OECD countries. Second, 2 types of panel cointegration tests (Pedroni and Kao) are used to establish a cointegrating (long-term equilibrium) relationship between fertility, female labour force participation and part-time employment of women. Then, 2 types of panel cointegration estimation techniques-FMOLS and DOLS- are utilized to estimate the regression equation. Finally, panel Granger causality tests are used to find the causality between these three variables.

4.1. Panel Unit Root Tests

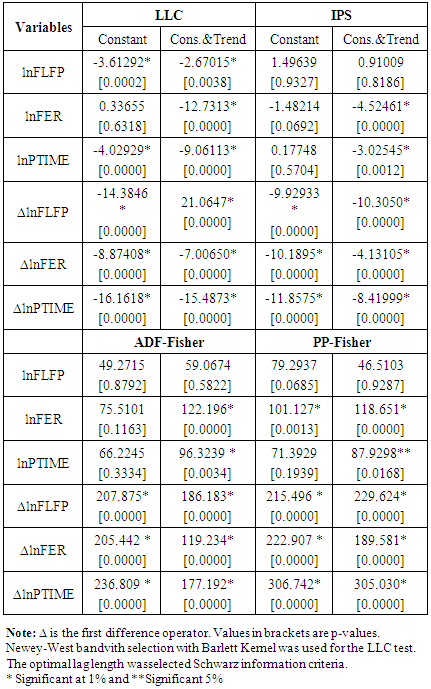

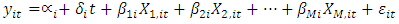

- The first step of panel cointegration analysis is to investigate the stationarity properties and to determine the order of integration of the variables. We use three panel unit root tests developed by Levine et al. (2002, henceforth LLC), Im et al. (2003, henceforth IPS) and ADF Fisher and PP-Fisher. The former two are widely used panel unit root analysis in the literature on panel cointegration. Among these, while LLC is based on the common unit root process assumption that the autocorrelation coefficients of the tested variables across cross sections is identical, IPS and ADF Fisher and PP-Fisher tests rely on the individual unit root process assumpiton that the autocorrelation coefficients vary across cross sections. The so called first generation panel unit root tests, notably the LLC and IPS tests, assume independence along the cross-sectional units.The LLC test proposed by Levin et al. (2002) is based on the following equation:

| (2) |

|

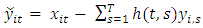

4.2. Panel Cointegration Test

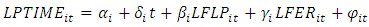

- Since the variables are I(1) we can conduct cointegration tests to examine the presence of a long-run equilibrium relationship between fertility, female labour force participation and part-time employment of women. Pedroni’s (1999) test that allows for heterogeneity in the intercepts and slopes of the cointegration equation.The application of Pedroni’s cointegration test requires estimating first the following long run relationship:

| (3) |

| (4) |

which is similar to the Phillips and Perron (1988) test, panel non-parametric (pp) and panel parametric (adf) statistics. The other group test is “between dimension” (group tests). These tests are “group mean cointegration tests” and allow for heterogeneity of parameters across countries. For the tests based on “within”, the alternative hypothesis is

which is similar to the Phillips and Perron (1988) test, panel non-parametric (pp) and panel parametric (adf) statistics. The other group test is “between dimension” (group tests). These tests are “group mean cointegration tests” and allow for heterogeneity of parameters across countries. For the tests based on “within”, the alternative hypothesis is  for all i, while concerning the last three test statistics which are based on the “between” dimension, the alternative hypothesis is

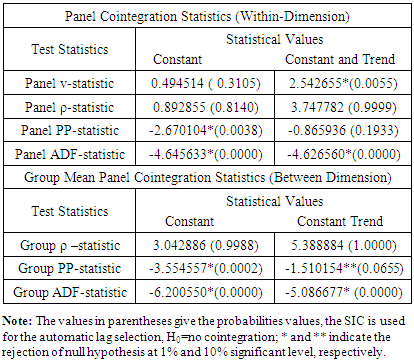

for all i, while concerning the last three test statistics which are based on the “between” dimension, the alternative hypothesis is  for all i.Table 3 shows the results of Pedroni (1999)’s panel cointegration tests where the null hypothesis is that there is no cointegration between fertility, female labour force participation and part-time employment of women, while the alternative hypothesis is that all variables are cointegrated. Although some of the statistics (in particular, panel-rho and group-rho) fail to reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration the results strongly support evidence of long-run cointegration relationships.

for all i.Table 3 shows the results of Pedroni (1999)’s panel cointegration tests where the null hypothesis is that there is no cointegration between fertility, female labour force participation and part-time employment of women, while the alternative hypothesis is that all variables are cointegrated. Although some of the statistics (in particular, panel-rho and group-rho) fail to reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration the results strongly support evidence of long-run cointegration relationships.

|

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

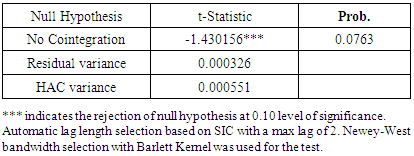

Table 4 provides the results of Kao (1999) panel cointegration test. The calculated value of t-statistic is greater than the critical value that indicates the rejection of null hypothesis of no cointegration. Thus, it can be concluded that the long-run relationship exists between female labour force participation, fertility and female part-time employment.

Table 4 provides the results of Kao (1999) panel cointegration test. The calculated value of t-statistic is greater than the critical value that indicates the rejection of null hypothesis of no cointegration. Thus, it can be concluded that the long-run relationship exists between female labour force participation, fertility and female part-time employment.

|

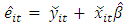

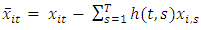

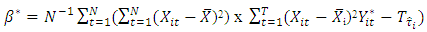

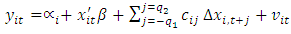

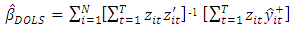

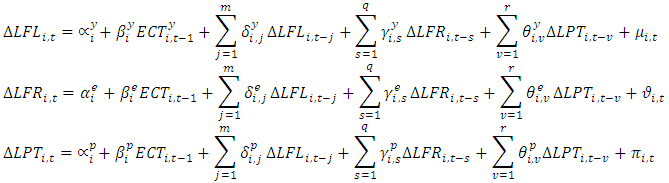

4.3. Panel Cointegration Estimation

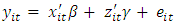

- Once the cointegration relationship is established, the next step is to estimate the long-run parameters. In order to estimate panel cointegration parameters are estimated by the group-mean panel FMOLS and DOLS methods developed by Pedroni (2000 and 2001). These estimators correct the standard pooled OLS for serial correlation and endogeneity of regressors that are normally present in long-run relationship. The test statistics derived from the group-mean estimators are constructed to test the null hypothesis. The FMOLS method produces reliable estimates for small sample sizes, also provide a check forthe robustness of the results. The group-mean panel FMOLS method is based on the following panel regression model:

| (10) |

and

and  are error terms and are accepted as stationary. The panel FMOLS estimator for

are error terms and are accepted as stationary. The panel FMOLS estimator for  estimator can be estimated as follows:

estimator can be estimated as follows: | (11) |

where

where | (12) |

illustrates long-run covariance matrix where

illustrates long-run covariance matrix where  is the ted sum of covariances, Li is the lower triangular in the decomposition of

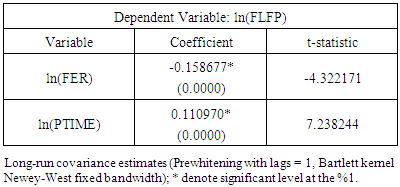

is the ted sum of covariances, Li is the lower triangular in the decomposition of  FMOLS regression is applied to Equation (1), to obtain asymptotically efficient consistent estimations in the panel series. Results for the panel FMOLS estimation of female labour force participation equations are presented in Table 5. The coefficient on the fertility rate is significantly negative in the case of OECD. Specifically, a 1% increase in fertility rate decreases female labour participation by 0.15%. The coefficient on the part-time employment of women is significantly positive. Specifically, a %1 increase in part-time employment of women increases female labour participation by 0.11%.

FMOLS regression is applied to Equation (1), to obtain asymptotically efficient consistent estimations in the panel series. Results for the panel FMOLS estimation of female labour force participation equations are presented in Table 5. The coefficient on the fertility rate is significantly negative in the case of OECD. Specifically, a 1% increase in fertility rate decreases female labour participation by 0.15%. The coefficient on the part-time employment of women is significantly positive. Specifically, a %1 increase in part-time employment of women increases female labour participation by 0.11%.

|

| (13) |

is the coefficient of a lead or lag of first differenced explanatory variables. The estimated coefficient of DOLS is given by:

is the coefficient of a lead or lag of first differenced explanatory variables. The estimated coefficient of DOLS is given by: | (14) |

is

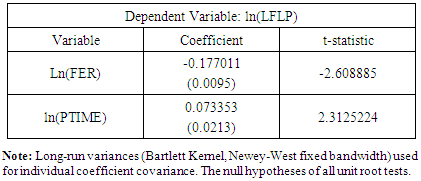

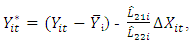

is  vector of regressors.Table 6 represents the results of panel DOLS regression. According to the panel DOLS results, ln(FER) is significant at 1% level and ln(PTIME) is significant at 5% levelin OECD countries. That coefficient of ln(FER)has negative sign where as the coefficient of ln(PTIME) has positive sign is compatible with the theory. That means 1% increase in fertility rate leads to a 0.18% decrease in the ln(FLFP) and 1% increase in part-time employment of women leads to a 0.07 increase in ln(FLFP) according to the DOLS model consequences.

vector of regressors.Table 6 represents the results of panel DOLS regression. According to the panel DOLS results, ln(FER) is significant at 1% level and ln(PTIME) is significant at 5% levelin OECD countries. That coefficient of ln(FER)has negative sign where as the coefficient of ln(PTIME) has positive sign is compatible with the theory. That means 1% increase in fertility rate leads to a 0.18% decrease in the ln(FLFP) and 1% increase in part-time employment of women leads to a 0.07 increase in ln(FLFP) according to the DOLS model consequences.

|

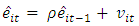

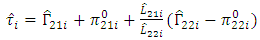

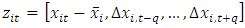

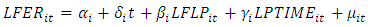

4.4. Panel Causality Test

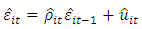

- Once the three variables are cointegrated, the next step is to apply the Granger causality test. In order to test for the existence of panel causality test using two-step procedure from Engle and Granger (1987) procedure. The Granger causality test is operated by estimating VECM. In the first step, we estimated the long-run model in equation (15, 16, 17) using FMOLS and obtain residuals in order to use in panel causality test as error correction term. For multivariate models, we have estimated ECTs as the residuals (it

respectively) from the following three separate equations:

respectively) from the following three separate equations:  | (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

where

where  is the error correction speed of adjustment parameter to be estimated, ECT is the error correction term,

is the error correction speed of adjustment parameter to be estimated, ECT is the error correction term,  are m parameters to be estimated,

are m parameters to be estimated,  are q parameters to be estimated,

are q parameters to be estimated,  are r parameters to be estimated, p, q and r represent the number of lags for the variables,

are r parameters to be estimated, p, q and r represent the number of lags for the variables,  are fixed parameter to be estimated and

are fixed parameter to be estimated and  are the error term. The sign of

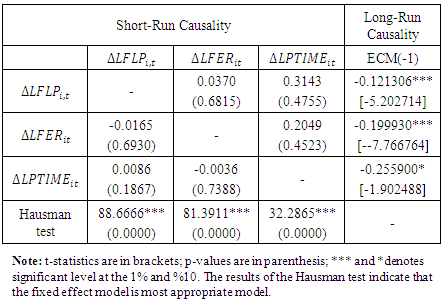

are the error term. The sign of  should be negative and its absolute value gives an idea of the speed of the adjustment process towards equilibrium.The results are presented in Table 7. The error corrected coefficient is significant and negative for the entire model. This result indicates that when there are deviations from long-run equilibrium, short-run adjustments in variables will re-establish the long-run equilibrium. The result also shows that there is no short-run Granger causality between variables.

should be negative and its absolute value gives an idea of the speed of the adjustment process towards equilibrium.The results are presented in Table 7. The error corrected coefficient is significant and negative for the entire model. This result indicates that when there are deviations from long-run equilibrium, short-run adjustments in variables will re-establish the long-run equilibrium. The result also shows that there is no short-run Granger causality between variables.

|

5. Conclusions

- The aim of this study was to estimate the relationship between female labour force participation rate, part-time employment and total fertility rate in 31OECD countries from 2000 to 2012. Recent developments in panel series econometrics modeling including Pedroni, Kao, Stock-Watson (DOLS) and FMOLS methods were employed to estimate the long-run relationship. In a panel framework unit root tests illustrated that the first difference of all the series are stationary. The results of residual-based panel cointegration tests of Pedroni and Kao pointed out the existence strong evidence that the variables have long run equilibrium for data set consists of 31 OECD countries.Our findings show that there is a negative effect on the female labour force participation rate of fertility rate in 31 OECD countries. It is important to understand what type of social policies can be designed to allow women to work and have children. On the other hand, perhaps more importantly, there are evidences that part time employment provides women easier to have job and inconsistency hypothesis is weaken. We believe that making part-time work more widely available could increase female employment rates. But we need to know whether part-time jobs cause social marginalization of women or not. Part-time jobs provide women an opportunity for flexible hours of work and allocate more time to their family responsibilities. In other respect, part-time work is criticized as a form of underemployment, paying lower wages and providing inferior fringe advantages comparing to full-time work. Surely, part-time work considered atypical work is extremely ‘gendered’ in all of 31 OECD countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Extended version of paper to appear in IV. Anadolu International Conference in Economics, June 10-12, 2015, Eskişehir, Turkey. The authors are thankful for the helpful comments of participant at this conference.

Notes

- 1. As the definition and conceptialization of part time job changes from country to country, mostly its official definiton i.e. “jobs less than 35 hours” is used in the literature.2. See Pedroni (1999) for detais of panel cointegration tests.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML