-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2017; 7(1): 1-14

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20170701.01

Analysis of Non-Oil Private Sector Investment Determinants (1980 – 2015): A Tool for Economic Diversification

Sally Okwuchi Uwakaeme

Madonna University Nigeria, Okija Campus, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Sally Okwuchi Uwakaeme, Madonna University Nigeria, Okija Campus, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study examines the relationship between non-oil Private sector investment (PINVn) and some generally accepted determinants of PINVn in Nigeria, spanning through 1980 to 2015, applying Johansen Co-integration technique, Unit root test and Error correction model. The empirical evidence demonstrates that, in the long run, positive relationship exists between PINVn and some determinants namely: non-oil GDP, non-oil foreign direct investment (FDIn) and non-oil credit to private sector (CRPn) but only FDIn is significant. Credit to government (CRG), foreign exchange rate (FXR), inflation rate, Government capital expenditure (GCE) and maximum lending rate (MLR) are inversely and significantly related. Savings has insignificant negative relationship. This result implies that CRPn, GCE, and national savings do not adequately complement investment funding and growth while inflation, high FXR depreciation and MLR, are implied constraint (risk) to return on PINVn. Credit to government seems to have a crowding-out effect on CRPn. The speed of the equilibrium adjustment, suggests a lag effect, indicating that PINVn in Nigeria responds slowly to the disequilibrium tendencies in these selected explanatory variables. Overall, the import of these findings implies that in the long run, these selected indicators are major determinants of PINVn in Nigeria. Therefore, there is need for sustainable price stability, economic efficiency driven by infrastructural development, enhanced technological capabilities, and fiscal discipline that would channel more funds to non-oil private sector production. Optimal lending rate that would reflect the overall internal rate of return on investment, with due attention to market fundamentals, should be adequately maintained. Stable polity and sustainable economic reforms to promote PINVn, should be highly emphasized to enhance diversification. Lastly, there is need for the policy makers to take cognizance of the lag effect and design policies in line with the expected magnitude of expected changes.

Keywords: Diversification, Non-oil Private Investment, Determinants, Unit Root and Co-integration Tests

Cite this paper: Sally Okwuchi Uwakaeme, Analysis of Non-Oil Private Sector Investment Determinants (1980 – 2015): A Tool for Economic Diversification, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-14. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20170701.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The effective management of an economy is critically dependent on the proper understanding of the interrelationships among the various components and sectors of the economy, as well as those factors that influence their dynamics. This is particularly relevant for economies that seek to move on the path of sustainable growth and development. It is also important in this regard, to bring to the front burner, those binding constraints to growth of the economy, which can only be effectively addressed, if policy makers can learn from the past experience.Nigeria, with her vast mineral resources, favorable climate and vegetation has a very good potential to diversify into both oil and non-oil private investment for a sustainable growth and development, but her sole dependence on oil as a major source of income has recently remained a major problem to her economic growth.Since 1970s, Nigeria has been a major oil producer, which accounts, on the average, for over 90.0 per cent of export receipts and about 70.0 per cent of government revenue. Presently, the Nigeria’s dependency on oil as the major source of income, together with the persistent global oil glut, has adversely affected her economic growth and development. (Nnanna et al 2004). [36]. Throughout the 1960s, agricultural sector was the most significant contributor to the GDP, foreign exchange receipts and government revenue until 1970s when the economy became dangerously dependent on oil as a result of the “oil boom.” and agricultural sector suffers negligence. Agricultural sector was also the highest employer of labour within the economy.Over the years, mono-cultural economic base, overwhelming dependence on crude oil export and unbridled import dependence, characterize the economic challenges confronting the policy makers and other stakeholders in the country. Consequently, the Nigerian government is presently in the fore front in growing the economy and among her cardinal economic objectives as a developing nation, is diversification into non-oil private investment and fostering sustainable growth and development. In pursuit of this objective, the Nigerian Monetary authorities have adopted (and are still pursuing) several reforms/policies, in line with neo-liberal thinking but much has not been achieved. Many reasons have been advanced for this development but the most apparent has been the poor investment climate/output. This has been attributed to many factors which include: low level of investible funds (particularly to non-oil private sector), excessive Government capital expenditure that are in most cases not channeled to adequate infrastructural development and productive sector of the economy, credit to Government which is believed to have a potential crowding out effect on credit to private sector, complex and inconsistent regulatory frameworks and policies, inflation, high lending rate, high rate of foreign exchange depreciation that affects importation of manufacturing inputs, among others. (Nnanna et al (2004) [36] as well as Ajide and Lawanson, (2012) [2]. All these problems have made it difficult for private investors to diversify into non-oil investment.Investment has been identified as a major factor in economic growth and development, and by extension, contributes to high rate of employment, productivity, capital formation, improved technology and poverty reduction. For the government to achieve its desired economic objectives, it must pursue policies that will enhance foreign and domestic investments in both public and private sectors. Although the prime motives of the two sectors are almost the same, they face the same challenges in financing and sustaining the investment requirements.Some lessons of experience have shown that government alone cannot drive the economy. A paradigm shift, under the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS), has also underscored the need for public/private sectors partnership as well as restructuring the system for efficient diversification and sustainable economic growth and development. However, Nigeria and some other African countries have failed to create the enabling environment that would encourage both domestic and foreign private investment in sufficient quantities, capable of bringing about diversification into non-oil investment and ultimately rapid economic growth and development. (Frimpang and Marbuah, (2010). [20] and (UNCTAD, (2012). [49].Economically, Kenya would be better off investing in Bee-keeping as an indigenous base for more development. Even with voluntary aid attracted by Honey Care Africa for this project, the people’s mentality does not seem to support sustainability in this area. (United Nations, (2015) [52]. Many countries in the coast that would have made fishing the base of their sustainable development have ignored this. Sierra Leone could have made Tourism a major development base.Generally, Africa is endowed with abundant natural resources, which if they are well managed, would provide sustainable base for development in many areas but the already enumerated problems coupled with the low standard of living of majority of most African populace, especially Nigeria. As far as sustainable development is concerned, the Nigeria’s experience is not encouraging when efficient management of resources for human survival are taken into consideration for both the present and future generations. (Waziri (2015) [53]. Some major obstacles are identifiable in addition to the problems already suggested. These include internal strife, lack of balance in all the sectors of the economy or inability of the government to diversify into other sectors. The priorities of the government are localized and of short term and non-attachment of adeuate importance to issues of social development like health care delivery and rural infrastructural development. In most cases, that is why economic growth may be progressing without sustainable economic development (Waziri (2015) [53]. Comparing both slow and fast growing economies, Nigeria’s investment/GDP ratio lags behind the required minimum level of an average of about 20.0 per cent of GDP annually that propelled the growth rate of those other economies (World Bank, (2012) [57]. For instance, in the South East Asia countries, investment/GDP ratio is about 35 per cent in Singapore; 38 per cent in Korea, and 41 per cent each in Malaysia and Thailand. Chile in South America registered 28 per cent. Malaysia, for instance, has adequately invested on palm production (non-oil) investment, among others. (World Bank (1998) [56], UNCTAD (2003) [48] and Bayraktar et al, (2007) [5]. This explains the growth rate of the Nigerian economy which closely followed the pattern of the growth rate of her capital goods investment. Consequently, there is need for diversification from oil as the only major source of economic earnings to non-oil investment in order to avert the cost of over-dependence on oil and thus, increase the present level of economic growth.In addition, the ownership of Nigerian manufacturing sub-sector is shared between the public and private sectors of the economy. In terms of number, the private sector-owned manufacturing units are predominant, while public sector investments dominate the capital intensive heavy industries sub-sector which is not adequately managed. Publicly owned heavy industries accounted for 66.7 per cent of total investment in capital goods while 33.3 per cent is for the private sector. (Bayraktar, 2007). [5] However, the recent government privatization programme has promoted the transfer of some of these firms to the private sector. Despite this development, non-oil Private sector investment in Nigeria still remains concentrated in the consumer good enterprises and had grown faster than the capital goods industries because of its relatively simple technology and lower capital intensive investment. This too affects national economic growth. (Mordi et al, 2010). [33]Generally, Nigeria has been classified as a low domestic savings and even lower investment country, especially in funding agricultural sector. Growth in Deposit Money Bank (DMB) credit to private sector in Nigeria has often exhibited volatile and in most cases negative trends. The DMB prefer credit to oil sector than agriculture. In December, 2013, the oil and gas sector recorded the highest growth rate of bank loan and advances, with a share of 24 per cent. The share of agriculture declined from 4 per cent in 2012 to 3.7 per cent in December, 2013. (CBN, 2013) [11]. Nigeria’s low domestic savings culture is attributed to among other factors, abject poverty and loss of confidence in the banking sector due to bank distress while the non-oil investors’ poor access to bank credit is mainly due to low credit rating by the DMBs. (Yesufu, 1996) [59].The sub-optimal performance of Gross Capital Formation could also be traced to low level of domestic savings, credit to private sector, inadequate physical and social indigenous technology as well as macroeconomic instability. (CBN, 2013) [9]. Macroeconomic instability manifests in high and volatile exchange rates, inflation rate and interest rate which made debt-financing investment unattractive as well as creating room for negative or low returns on investment and these discourage non-oil private investment, especially when financed with bank loans. (Serven and Solimano 1992). [42] Thus, both domestic and foreign private investors are wary of investing in countries where basic requirements are inadequate and the return on investment unguaranteed. This, ultimately results to dearth of long term projects, high rate of unemployment and abject poverty. (Motley, 1998) [35] as well as (Asante, 2000) [4].Furthermore, Nigeria’s economic climate has not been able to attract private foreign investment to its fullest potentials, given the precarious operating environment which has limited domestic private investment when compared with other countries, competing for global investment capital.(Ajide et al 2012) [2]. Ikhsan (2003) [26] and UNCTAD (2003)) [48]. Although, cumulative foreign private investment received in 2014 (N12786.70 billion) seem appreciable when expressed in domestic currency (Naira), it should be realized that the exchange rate of Naira has been suffering massive depreciation since 1986 till date. (CBN, (2014) [10]. To get out of this non-oil low-investment trap, it has become pertinent to examine the determinants of non-oil private sector investment in Nigeria as well as factors which scuttle diversification and the translation of investments into growth. The outcome will enhance effective economic planning for diversification and reasonable investment opportunities for efficient growth of the economy.However, most of the economic scholars are of the view that the problems of Nigeria’s non-oil private investment have not been well understood and thus, not well-managed. Some of the reviewed related studies like Nnanna et al (2004) [36] as well as Green and Villanveva (1991) [23] have some methodological and conceptual problems that undermine their accuracy and thus their efficacy for effective policy response. For instance, non-application of unit root test to reduce or if possible eliminate spurious regression due to non-stationary properties of time series, may lead to bias inferences. Engel and Granger (1987) [19] and Gujarati et al (2009) [24]. Green and Villanveva (1991) [23] also used cross-section analysis which precludes country’s specifics which may also lead to misleading result. The reviewed studies also did not apply disaggregate analysis of private investment except Mordi et al (2010) [34] but the variables and periods of observation used were very limited.Recognizing the above gaps and challenges of the previously reviewed studies, there is need to reexamine the problem holistically by applying more Nigerian time series using disaggregate analysis method of private investment and basic analytical econometric techniques (Co-integration, Unit root test, Error Correction Mechanism (ECM) to see if a more authentic result could be achieved for effective economic planning. The main objective of this study is therefore, to empirically establish major non-oil private sector investment indicators by determining the relationship between non-oil private investment and some selected and generally acceptable determinants as well as identifying the factors that constrain their growth in Nigeria. This is the first step to solving the problem of diversification into non-oil private investment. To achieve this objective, the hypothesis below is formulated to aid the analysis:There is no significant long run relationship between Non-oil Private Sector investment proxies by Gross Capital Formation and some generally accepted major determinants namely: Non-oil Credit to Private sector, Credit to Government, Non-oil Gross Domestic Product, Non- oil Foreign Direct Investment, Government Capital expenditure, National savings ratio, Domestic Maximum lending rate, Annual Inflation rate, and Nominal Foreign exchange rate.The paper is structured as follows: Section I which precedes four other sections, introduces the study. Section II discusses the related reviewed literature. Section III provides the methodological issues. Section IV presents and analyses the data while section V concludes the study with policy recommendations.

2. Review of Related Literature

- This section offers an overview of conceptual, theoretical and empirical review of related literature on private sector investment and its determinants in relation to both developed and developing countries’ experiences.

2.1. Conceptual Issues

- The term, Private investment, can be broadly defined as acquisition of an asset by non- public or non-governmental groups or individuals with the aim of receiving a positive return (Stieglitz, 1993) [43]. It could also mean the production of capital goods, which are not consumed but instead used in future production. Investment is also usually measured in terms of physical capital formation, in which case, investment is regarded as an addition to the stock of capital. In other words, gross capital accumulation is the driving force of any national investment. (Ajakaiye (2002) [1] and Nnanna et al (2004) [36]. At the macroeconomic level, investment expenditure in Nigeria in terms of financing is structured into domestic and foreign segments depending on sources of finance and to a lesser extent, management. At the domestic level, investment is further categorized into public and private sector investment expenditures. Foreign investment may also include foreign direct investment, foreign private investment and portfolio investments, whether such expenditure is financed by private or official sources of capital. (Contessi and Weinberger, 2009) [14] as well as World Bank (2012) [57].Investment could also be evaluated from the sectorial distribution point of view, in which case, each group of activity sectors of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is examined to measure the quantum of investment expenditure received over time. In this categorization, the structure of investment or Gross Capital Formation is composed of building and construction, land development, transport, machinery and equipment and breeding stocks. (CBN 2013) [11] and (Nnanna et al, 2004) [36].The Gross national investment is comprised of public and private sector investments. The public or government sector investment is defined as comprising all units of government investment that implement public policy by providing non-market services, which is determined collectively through a decision making process and whose allocation is based according to the stressed needs of the final consumers. These are financed mainly by compulsory levies and taxes on other sectors of the economy. The government sector provides public goods and services with funding from the public treasuries. The government sector is also known as public sector largely as a result of the characteristics of the type of goods and services the sector provides. Mordi et al (2010). [33]Due and Friedlander (1977) [17] described public goods as possessing the basic characteristics of non-appropriate, non-rivalry, non-excludable consumption. Public goods are individually and collectively consumed such that the consumption of one individual does not reduce the amount available for others. These characteristics make it difficult to package public goods for sale under conditions of market mechanism. Examples are roads and highways, defense and national security, airport, environmental protection, etc. These characteristics render price mechanism ineffective in allocating resources efficiently in a market economy, thus providing rationale for government sector intervention in order to ensure efficient resource allocation, income redistribution, and attainment of stabilization of the economy. This is in contrast to the private sector that engages in production and sale of private goods. Conversely, Private goods are divisible and individually consumed, while consumers preference can be ascertained through effective demand. Consequently, private goods can be offered in markets and individuals that cannot pay for it are excluded from its consumption in the absence of effective demand. The motive for private investment is primarily for profit while public sector investment is geared at enhancing public interest, private investment and market system in order to promote synergy between government and private sector for economic growth and sustainable development, (Mordi et al, 2010) [33]. There is therefore need for both the government and the private sector partnership in order to achieve sustainable development. Sustainable development here is understood as the type of development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to also meet their futures needs The two key concepts are needs and limitations, The development must meet the essential needs of the people and its relevance must not be limited by any economic or social situations. (Lele (2015) [28] and United Nations, (2015). [52]Investment could be either private or public but diversification here entails shifting emphasis from a single sector of the economy which is crude oil as sole source of income to other real sectors which include agriculture, industrial sector, etc, driven by private sector, in order to increase production capacity, national income and ultimately for diversification of the risk of sole- dependence on oil during economic crises.. This is believed would create basis for sustainable economic growth and development.

2.2. Theoretical Review on Investment

- Ever since Keynes, who was one of the pioneers of investment theories, analyzed that there is ex post quality between savings and investment, the offshoots of his submission later brought about some other investment theories like accelerator theory of investment, neoclassical theory, Tobin’s Q theory and expected profit model. Hence these theories were theoretically identified to model investment in the existing investment literature. The accelerator theory basically postulates that investment is a linear function of changes in output. This investment is made possible in the sense that the savings/income generated is the money invested. However, a more general form of acceleration theory assumes that the larger the gap between the existing capital stock (infrastructure, human resources and physical assets) and the desired capital stock, the greater the country’s required revenue to be generated and the required rate of investment. Some scholars posit that the accelerator theory performs well empirically, because time series evidence has always revealed that lags of output are highly correlated with investment and by extension, savings/income generated (Bayraktar and Fafack, 2007) [5].Furthermore, there are several motives for investment but the basic motive is profit/return. According to Keynes’s theory, this motive depends on the expected marginal efficiency of capital in relation to the expected interest rate. The difference between the realized marginal efficiency of capital and rate of interest is the opportunity cost of investment. The theory assumes that expected return on investment is intrinsically volatile in view of the uncertainty which accompanies the main determinants of investment returns. (Rodrik, 1991) [40] and Nelson et al (1982) [37]. Therefore element of uncertainty is introduced as another key determinant of private investment. In the context of growth, the accelerator principle suggests that increase in output leads to increase in investment, thus relating investment to GDP. (Zebib and Muoghalu, 1998) [60] and (Lensink and Morrissey, 2001) [29].The Tobin (1969) [47] Q theory emphasizes the relationship between the increase in the value of the firm due to the installation of additional capital and its replacement cost. Investment, therefore, is a function of difference between the market value and the additional unit of capital and its replacement cost. This ratio (known as marginal (Q) may differ from unity due to delivery lags, adjustment and installation cost. However, the theory has been criticized on the following grounds: marginal and average Q will differ if firms enjoy economies of scale or market power; the assumption of increasing installation cost is unrealistic; the cost of additions to an individual firms capital stock is likely to be proportional or even less than proportional to the volume of investment, because of the indivisibility of many investment project.Furthermore, theoretical and empirical literature have proved the link between investment, finance and income output. All growth models have come to accept that the rate of growth of an economy is determined by the accumulation of physical and human capital, the efficiency of resources used and the ability to acquire and apply modern technology, (World Bank, 1993) [55] and (United Nations, 1993) [50]. In turn, finance is postulated as an important determinant of investment. (World Bank, 1993) [55]. Financial institutions must pool savings and then direct them to viable investments in the form of credits. (Copeland Weston, 1990) [15]. This is the so called supply leading theory of finance. Accordingly, the desire to achieve high and sustainable economic growth requires mobilization of savings that can be channeled to investment in the form of credit (Nnanna et al 2004) [36]. Consequently, the quality, cost and availability of loanable funds can enhance expansion of private investment.Mckinon (1973) [32] and Shaw (1973) [41] who formulated the neoliberal approach to investment stressed the importance of financial deepening and high interest rates as drivers of economic growth. According to them, if an economy were free from repressive conditions, this would induce savings, investment and ultimately, economic growth. In their view, investment is positively related to real interest rate in contrast with neoclassical theory. An increase in interest rates will lead to an increase in the volume of financial savings thereby raising investible funds, a phenomenon that Mckinnon (1973) [27] calls the “conduit effect”. From the brief theoretical exposition, it is discernable that private investment time series could be drawn from different schools of thought namely: Keynesian, neoclassical, neoliberal and uncertainty, although each of them has its inherent drawbacks.

2.3. Related Empirical Review

- Financial constraints on investment are gaining prominence in the literature. Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) [43] in their work concludes that at the micro level, firms may be facing binding financial constraints in domestic capital markets because interest rates are controlled or subjected to endogenous credit rationing by financial institutions. According to them, restrictive monetary and credit policies affect investment by increasing the real cost of retained earnings as well as the user cost of capital which lead to reduction in investment.Green and Villanveva (1991) [23], extended the neoclassical model by incorporating factors such as macroeconomic instability (inflation), macroeconomic policies (monetary, fiscal, and exchange rate), the incentive structure and response to it, risk and irreversibility, and credibility of policy reforms as major determinants of private investments. They concluded that risk plays a vital role in investment decision because it is irreversible. According to them, the decision to invest or postpone investment depends on the perception of the magnitude of risk by the investor. On the other hand Arrow (1968) [3] suggests that investment can be considered irreversible in an extreme situation. This implies that investment decisions can be viewed from the perspectives of irreversibility and reversibility. Under conditions of certainty, irreversibility creates a wedge between the cost of capital (interest rate) and its marginal contribution to profit. Under conditions of uncertainty, due to macro instability, irreversible investment can be adversely affected by risk factor.Mordi et al (2010) [34] in their study on determinants of non-oil private investment in Nigeria using Vector Auto-regression model, confirmed that risk was an important factor in investment decision, likewise income output for non-oil investment and the lag of the dependent variable (Gross fixed capital formation) but they did not incorporate interest (lending) and foreign exchange rates in their explanatory variables which are relatively important. Additionally, Bernanke (1983) [6], as well as Bertola and Caballero (1990) [7] in their study suggest that under uncertainty, firms acquiring additional capital presently stand the risk of being stuck with excess capacity in future and can be costly to eliminate. This notion amplifies the importance of uncertainty in investment decision making. The problem of uncertainty is more severe in developing countries where transformations inherent in development such as establishing new industries and absorption of new technologies and inflation heightens uncertainty (World Bank 1993) [54].Chenery and Bruno, (1962) [13], in their study, argue that when investment/GDP ratio consistently exceeded the Savings gap ratio, it implies that domestic savings was insufficient to fund the required investment. This is the savings-Gap model and it points to the need for external finance to supplement domestic resources.Similarly, Chadra and Sandilands (2002) [12] using various concepts of investments such as private investment, government investment, total investment and fixed investment to investigate the issue of causality, came up with the basic conclusion that in India, capital accumulation is the result rather than the cause of growth. These findings suggest that policies aimed at increasing the rate of savings and investment should be vigorously pursued.Omotor, (2007), investigated the impact of monetary policy on the Nigeria real sector aggregate output and confirmed that interest rate (maximum lending rate) has a negative impact on the output (agricultural and manufactures sectors) Likewise Nwosa et al (2012). [39]EFinA (2012) [18] opined that the private sector investors (non-oil), specifically Small and Medium enterprises’ Creditworthiness is poorly rated and as a result has very limited access to financial services in Nigeria. Luper (2012) [30] in his studies also confirmed same. Their inability to access capital or adequate credit from Money Deposit Banks has adversely affected private investment.Sitta, (2005) [45] in his studies has shown that fiscal incentives provided by government are not particularly very important to private investors in determining their decision to invest or not based on the official bureaucracy attached. In some countries like Nigeria, investors may be required to apply for the fiscal incentives, while in others, these incentives may be granted automatically once decision to invest has been made. However, it has also been confirmed that investors still admit that fiscal incentives have a way of improving their bottom lines even though they do not deem it very important. KPMG (2012) [27] and NIPC (2009) [38]. Furthermore, the IMF in World Economic Outlook (2012) [58] is also of the view that fiscal incentives are successful in enhancing private investments in countries with strong institution, good and adequate infrastructural facilities, adequate regulatory and legal framework as well as good enabling investment environment. These factors have ameliorated the cost of doing business and attracted investment to these countries. However, the implementation of fiscal incentives in Nigeria is undermined by weak institution, unstable macroeconomic indicators, poor infrastructural facilities, poor monetary policy monitoring/evaluation, poor supervisory framework, corruption, political instability and lack of transparency and fairness in taking decisions on fiscal incentives in Nigeria. These have hampered the growth of non-oil private investment.

3. Methodological Issues

3.1. Estimation Technique and Procedure

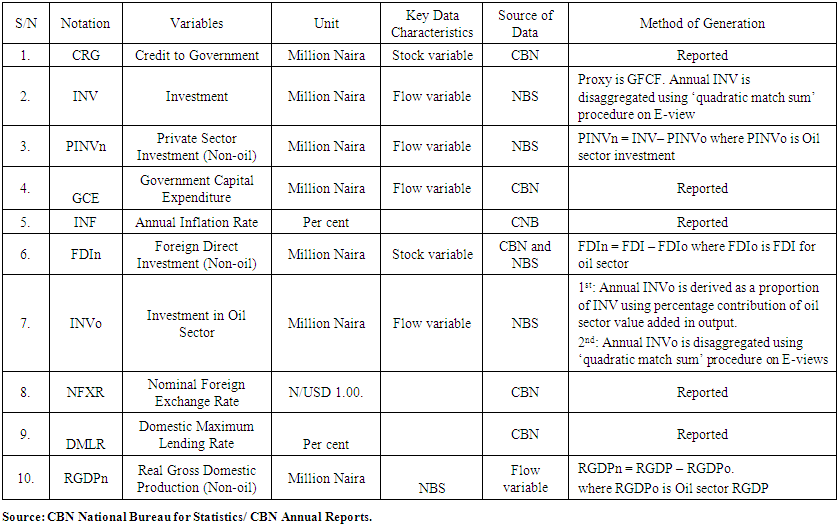

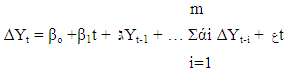

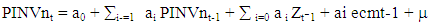

- The study applied econometric analytical techniques based on co-integration, unit root test and Error correction mechanism (ECM) for the data analysis while data is obtained from CBN Statistical Bulletin, National Bureau for Statistics, and CBN Annual Reports and Statement of Accounts various issues, spanning from 1980 to 2015 for the purpose of arriving at a dependable and unbiased analysis. Prior to testing for long-run relationship using co-integration test, the level series OLS regression was applied at first stage to test for long run relationship between Non-oil private investment and the selected explanatory variables. However, being conscious of the characteristics of the time series used, careful note was taken on the properties of the stochastic error terms that might have entered the model which could give rise to spurious regression. Consequently, a further rigorous investigation was carried out using Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) (1981) [16] unit root test to check the stationary property of the variables (if any) in the model. The purpose of Unit root test is to establish if the time series have a stationary trend, and, if non-stationary, to show the order of integration through ‘differencing’. A time series is stationary if its means, variance and auto-variance are not time- dependent. (Nelson et al 1962) [37]. The assumption is that the time series used for this research have unit root stochastic process. The process could be represented as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

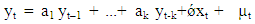

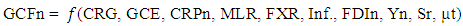

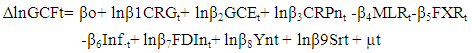

3.2. Model Specification/Analytical Framework

- Key components of non-oil Private Investment sector are agriculture, manufacturing, building and construction, wholesale and retail. Production in this sector is influenced by cost of funds (domestic maximum lending rate). The suppliers of credit to this sector is assumed to require a risk premium in the interest rate charged on loans because participants in this sector are mainly small and medium scale enterprises with low credit ratings compared with government sector.The quantum of credit available to private sector, determines to a great extent, the production capacity but in most cases, banking system credits are not optimally channeled to productive private investment for some reasons which include the above. (Nnanna et al 2004) [36]. In addition, government influence on non-oil private investment comes through two major channels – credit to government and Government Capital expenditure which are assumed to complement private investment. Public infrastructure acts as a catalyst to investment production. The extent government expenditure has been channeled to provide this infrastructure will also influence private investment.In specifying the determinants of non-oil investment, it is assumed that increase in the availability of financial resources will lead to higher level of investment in the economy. The FDI indicates exposure of the domestic economy to the external sector. Credit to government for a typical capital-constrained developing country may have a potential crowding out effect on private borrowing since government with higher credit rating, competes with the private sector for limited cash balance.It is also assumed that private investors could (and regularly do) exercise the option to wait in investment decisions when the macro economy is too volatile to accommodate their investment. In particular, returns from investment are discounted for sunk costs which are partially or wholly irreversible as well as the probability that other associated costs might not be fully recovered in a difficult- to- predict environment as it is obtained in Nigeria. The structural characteristic of the economy, which is risk and profitability of both foreign and domestic investment, therefore depend on inflation, interest rate and the exchange rate. The significant of risk does not only influences the investment decision but it also affects how much to save and thus contributes to low savings rate and capital flight. Additionally, the degree of distortion reduces the propensity to invest and hence potential output. In line with the acceleration principle, domestic output plays a critical part. Invariably, factors that constrain savings such as inflation, and those that constrain inflow of resources like exchange rate are taken into account. Thus, non-oil Private investment (PINVn), proxies by Gross Capital Formation (GCF) as applied in Mordi et al (2010) [34] is therefore specified as a function of the selected and generally accepted determinants given below. All variables except inflation, interest rate and exchange rate are reduced to logarithm form to make calculation less tedious. The functional and linear mathematical relationships are specified as follows:

| (4) |

| (5) |

4. Data Presentation and Analysis of Empirical Findings

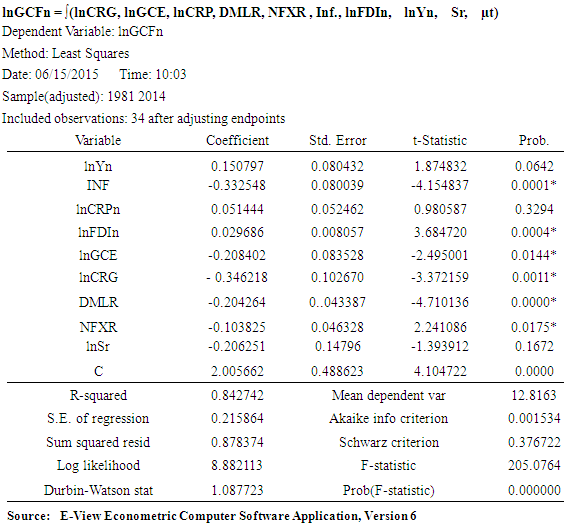

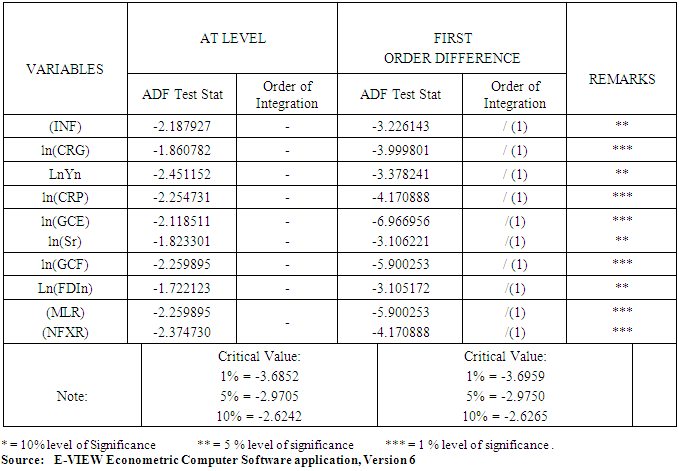

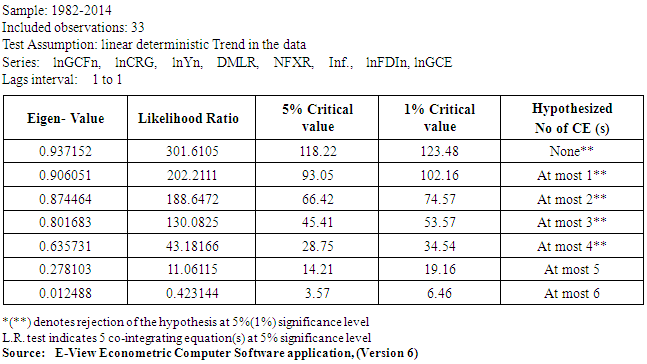

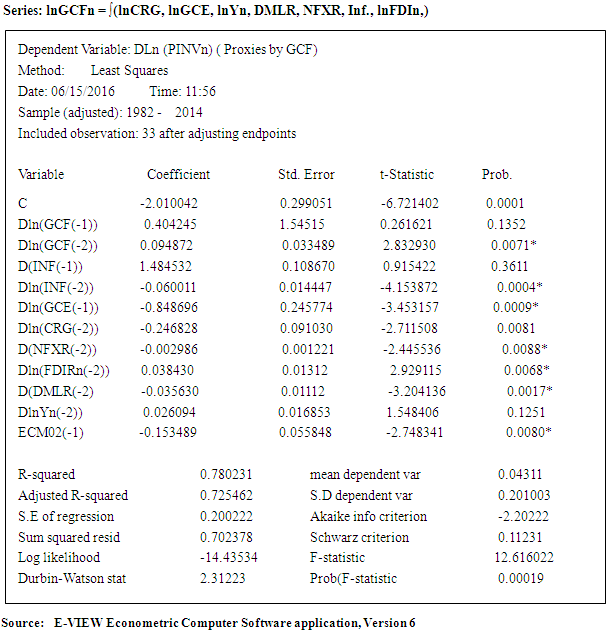

- This section presents the data, the empirical results and discussions on the relevant findings from the model specifications tested in this study. Table 4.1 below shows the summary of empirical result when OLS multiple regression is run at the level series.Data Presentation

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

- The study empirically examined the relationship between Non-oil private investment and some selected and generally accepted determinants of non- oil investment in Nigeria, spanning from 1980 to 2015, using time series sourced from CBN publications. The study has brought to fore that these selected investment indicators are major determinants of non-oil private sector investment in Nigeria and could be harnessed to enhance diversification and production capacity in order to reduce the present level of sluggish and volatile growth of the economy.

6. Policy Recommendations

- Based on the analysis of the findings, the study recommends:1. Government should strive to achieve sustainable price stability, economic efficiency driven by infrastructural development and enhanced technological capabilities to increase private sector production capacity. 2. The optimal interest (lending) rate should reflect the overall internal rate of return on private sector investments with due attention to market fundamentals. This will stimulate credit demand and diversification into non-oil private investment.3. Maintenance of fiscal discipline by channeling funds to the productive sector of the economy and drastic reduction of the amount of Deposit Money Banks credit to the government should also be highly emphasized. This could eliminate or at least, check the excessive crowding-out effect of credit to Government sector on private sector borrowing.4. Adequate policies/reforms and surveillance should be maintained to ensure proper foreign exchange utilization to minimize market malpractices. CBN should also minimize being the sole supply of foreign exchange. Additionally, encouraging increase in local production of, and value added to primary commodities and manufactured products, will also curtail excessive pressure on foreign exchange demand by importers. 5. Stable polity and sustainable economic reforms should be increased to promote both domestic and foreign investments. This will enhance diversification.6. Economic reforms that would help to restore more confidence in banking system and increase in rural banking services will also enhance more domestic savings culture.7. Having noted major determinants/constraints from this study, there is an urgent need to strive and diversify the Nigerian economy into non-oil private sector investment for healthy and sustainable growth and development in order to increase her reserve, especially with this present persistent global oil glut.8. Lastly, there is need for the policy makers to take cognizance of the lag effect and design policies in line with the expected magnitude of expected changes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author wishes to acknowledge and appreciate all those who in one way or the other contributed immensely to the development of this paper, especially Prof. Steve Ibenta, of Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State Nigeria and Prof. Iheduru of Madonna University, Nigeria, for their time in vetting this work.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML