-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2016; 6(1): 72-78

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20160601.09

Impact of Abnormal Audit Fee to Audit Quality: Indonesian Case Study

Fitriany, Sylvia Veronica, Viska Anggraita

Fakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia

Correspondence to: Fitriany, Fakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study investigates the economic bonding between auditor and client by examining the association between abnormal audit fee and audit quality with Indonesian setting where there is high audit market competition and strong client bargaining power because of regulation on mandatory audit firm rotation. We found that positive abnormal audit fees are negatively associated with audit quality and imply that the audit fee premium is a significant indicator of compromised auditor independence due to economic auditor–client bonding. Audit fee discounts could also increase audit quality, maybe due to the mandatory audit firm rotation and high audit market competition in Indonesia, so that the auditor must keep their independency and high audit quality to maintain good reputation.

Keywords: Auditor–Client Economic Bonding Abnormal Audit Fees, Audit Quality, Auditor Independence

Cite this paper: Fitriany, Sylvia Veronica, Viska Anggraita, Impact of Abnormal Audit Fee to Audit Quality: Indonesian Case Study, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 72-78. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20160601.09.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Abnormal audit fees is the difference between actual audit fees paid to the auditor (for the annual financial statement audit) and the expected normal level of fees that should have been charged for the audit engagement effort (Choi et al., 2010). Based on this definition, audit fees could be separated into two components normal audit fees and abnormal audit fees. Normal audit fees are considered to capture the effects of the regular audit effort costs (i.e., personal expenses for the audit team, litigation risks, and normal profit margin for the audit engagement, whereas abnormal audit fees are determined through a non-transparent, and therefore, unobservable auditor–client agreement. According to the algebraic sign, abnormal audit fee could be separated into negative abnormal audit fee (below normal audit fees or fee discounts) or positive abnormal audit fee (upper normal audit fees or audit fee premiums). Previous research related to abnormal audit fees and audit quality find a mixed result. From 6 study which uses variable abnormal fees, there are 3 studies found a positive association between abnormal audit fees and audit quality (Eshleman and Guo (2013); Mitra et al. (2009); Higgs and Skantz (2006)), 3 studies found a negative relationship between abnormal audit fees and audit quality (Hoitash et al. (2007); Hribar et al. (2010)) and 1 study found no signifi cant relation (Xie et al., 2010). Contribution of this research area, first, prior empirical studies in the field of abnormal audit fee pricing provide mixed results (e.g., Mitra et al. 2009; Choi et al. 2010; Asthana and Boone 2012; Blankley et al. 2012, Kraub et al., 2015). Given these mixed results, our study provides additional empirical evidence on the association between abnormal audit fee and audit quality. Second, previous studies in this research area mainly focus on the United States (US) audit market and a one in China and German audit market. There is no research in developing country yet. The different institutional characteristics of Indonesia in comparison to the US such as (1) the relatively less restrictive auditor’s liability regime, (2) the prevailing two-tier (vs. one tier) corporate governance system, (4) the relatively lower public enforcement will create different result. Third contribution, there are mandatory audit firm and audit partner rotation in Indonesia, while in the US there is no mandatory audit firm rotation, only partner rotation. Mandatory audit firm rotation rules increase audit market competition between BIG4 and second tier audit firm especially for listed company client. With high competitive audit market, maybe it will result a strong bargaining power of clients in the determination of audit fee, therefore it may cause negative abnormal audit fees (fee below normal). In the high audit market competition, high risk litigation and strict oversight, abnormal negative fee probably will not decrease the audit quality, because the auditor will always maintain their reputation and avoid litigation.

2. Literature Review

- Kraub et al (2015) summarize previous studies investigating the association between abnormal audit fees and audit quality (see table 1). Audit quality proxy for the majority of prior research is discretionary accruals. Another surrogates for audit quality are financial restatements, audit opinions, analysts’ earnings forecasts, earnings response coefficients, fraud incidences, or SEC comment letters, respectively, are used as surrogates for audit quality. There are 6 studies which examine only the abnormal audit fees and 5 study have been distinguished positive and negative abnormal audit fees. That studies show a mixed results. Possible reasons for the mixed findings are difficult to resolve as different samples, sample periods, audit quality measures, estimation models and control variables are used. it.Kinney and Libby (2002), Choi et al. (2010) states that accounting firms that receive high abnormally audit fees have an incentive to allow the client engage in opportunistic earnings management. Krauß et al. (2015) also found audit fee premium is a significant indicator of compromised auditor independence due to economic auditor–client bonding. This is consistent with economic theory of auditor independence from De Angelo (1981a, b) which the desire to maintain a favourable audit engagement (with abnormal high audit fee) is trade off with the cost of litigation over the possibility of damage to reputation (Johnson et al. 2002). So, if the perceived net benefits are greater than the associated costs, the economic bonding effect will increases and audit quality will decreases simultaneously.On the other hand, Gupta et al. (2009) and Blankley et al. (2012) found that audit quality may decrease as auditors received audit fee that is lower than normal (discount). The lower audit fees maybe because the client have strong bargaining power in the bidding process (Barnes 2004). If the fee is lower than normal, accounting firm will adjust their audit efforts, reduce their audit procedures such as reducing the number of hours of audit, put less experienced staff, etc (Gregory and Collier 1996; Eshleman and Guo 2013).Choi et al (2010) said that abnormal audit fees can be viewed as what De Angelo (1981) called “client-specific quasi-rents”. The existence of (positive) client-specific quasi-rents creates an incentive for the auditor to compromise independence with respect to a specific client (De Angelo 1981; De Fond et al. 2002; Chung and Kallapur 2003).Base on that research, we conclude that audit quality will be impaired when auditors are overpaid. When the auditor receives unusually high audit fees from a client, the auditor will tolerate the client to engage in opportunistic earnings management because the benefits to the auditor can outweigh the associated costs (e.g., increased litigation risk, loss of reputation). Therefore our hypothesis:H1: Positive abnormal audit fees are negatively associated with audit qualityThe contribution of this study is to analyze the adverse consequences of the economic ties of -charge abnormal audit- on audit quality in the audit market in developing countries such as Indonesia. Indonesia has different institutional characteristics with the United States where the majority of previous studies have been conducted. Kraub et al. (2015) stated four argument about the necessity of examine the relationship between abnormal audit fee and audit quality in Germany environment, instead in US only. The civil liability for auditor’s misbehaviour is sanctioned differently in Indonesia and the US. In the US, the liability of compensatory damages is unlimited (Quick and Warming-Rasmussen 2009), while in Indonesia there are no rules regarding the amount of compensation. The lower litigation risk of the auditor within the Indonesian environmental context is expected to negatively affect audit quality when the magnitude of positive abnormal audit fees increases. Negative abnormal audit fees might also decline audit quality in the Indonesia environmental context as a reduced audit effort is likely to result in lower (potential) litigation charges. Second, Indonesia follow a two-tier corporate governance structure while US is a one-tier corporate governance system. The US one-tier setting is primarily characterized by the board of directors, whereas corporate structure in Indonesia consists of the executive board and the supervisory board where the executive board is responsible for strategic and operational decision making, while the supervisory board appoints and monitors the executive board. The supervisory board maintains networks with stakeholders. The monitoring task of the supervisory board also comprises the examination of the financial statement reporting process which is supported by the findings and remarks of the statutory auditor. So, the statutory auditor can be seen as a close partner or agent of the supervisory board. Due to the clear segregation of duties with regard to executive power and oversight, we assume that the net economic bonding incentives for auditors in Indonesia (two-tier setting) are smaller than in US (one-tier setting) where the segregation of duties is not that strong. Consequently, we expect the Indonesia governance system give positively affect audit quality when positive abnormal audit fees are paid. In case of below-normal audit fees, audit quality might also differ systematically in the two jurisdictions when the supervisory board or respectively, audit committee renegotiates, the financial terms of the audit differently; inducing a lower audit quality level when the auditor reduces her effort in order to make the audit engagement profitable (Telberg 2010; Blankley et al. 2012).Third, disclosure requirements and legal protection of minority shareholders against expropriation by corporate insiders is less restrictive in Indonesia compare to the US.Information asymmetry between the management and the owner of the cooperation is higher in Indonesia compare to US which relatively dispersed shareholders, strong outside investor protection, and large equity markets like the US exhibit lower levels of earnings management than Indonesia with relatively concentrated shareholders, weak investor protection, and less developed equity markets (Leuz et al. 2003). We expect the less restrictive institutional environment in Indonesia in comparison to the US, will increase auditor’s net economic bonding incentives, and thus, when positive abnormal audit fees are paid, it will negatively affect audit quality. Furthermore, negative abnormal audit fees are likely to result in a relatively lower audit quality when being reflective of a reduced audit effort or a stronger client bargaining power, respectively.Choi (2012) also said that when the audit fees are lower than normal (i.e., abnormal audit fees are negative), there is three possibilities:First, auditors have few incentives to compromise audit quality by accept to client pressure for substandard reporting (will tolerate the client to engage in opportunistic earnings management). This is because the benefit to auditors from obtaining these unprofitable (or only marginally profitable) clients is not great enough to cover the expected costs associated with substandard reporting (e.g., increased litigation risk, loss of reputation). Therefore it is expected that there is an insignificant or weak association between abnormal audit fees and the magnitude of discretionary accruals (audit quality).Second, it is also possible that auditor have lower incentives to compromise their independence because of reforms such us SOX which increase oversight on auditors. This reform will make the auditor limit the magnitude of discretionary accruals made by client. Therefore it is expected that there is a negative association between abnormal audit fees and discretionary accruals for clients with negative abnormal audit fees (positive association to audit quality).Third, when auditors bear low audit fees in anticipation of high audit fees from future profitable engagements (and thus abnormal audit fees are negative in the current period), auditors can be vulnerable to client pressure for allowing biased financial reporting. To the extent, discounting of current fees harms auditor independence. Therefore it is expected that there is a positive association between abnormal audit fees and the magnitude of discretionary accruals for clients with negative abnormal fees (negative association to audit quality). Given the three previous possibilities on the effect of negative abnormal audit fees on audit quality, it is an empirical question whether the association between negative abnormal fees and discretionary accruals (audit quality) is positive, negative, or insignificant for clients with negative abnormal accrual. Therefore, we have no directional prediction on this association.H2: Negative abnormal audit fees are associated with audit quality.

3. Research Design

3.1. Measurement of Abnormal Audit Fees

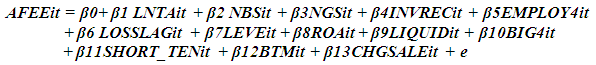

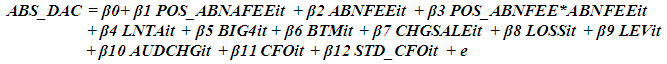

- Measurement of Abnormal Audit Fees The demand for audit services is a positive function of the three audit engagement factors: (1) client size, (2) client complexity, and (3) audit engagement specific risk such as the risk of the client and the auditor (Craswell et al. 1995; DeFond et al. 2002; Hay et al. 2006; Choi et al. 2010). Abnormal audit fees are the difference between the actual audit fees paid and the normal audit fees estimated (Francis and Wang 2005; Mitra et al. 2009). Abnormal audit fee model is as follow:

| (1) |

| (2) |

4. Sample and Data

- This research uses companies that are listed on Indonesian Stock Exchange (BEI) from2012 to 2013. Data collected from the Thomson Reuters Eikon and Annual Report each company. It uses purposive sampling method, which includes only listed companies (in BEI) during sample period, and excludes financial companies (ie. banks, insurance and investments corporations) because those companies have special financial statements structure so that their earning quality measurement does not equal with the other industries. Company in Indonesia start to disclose audit fees since 2011, but only a few companies which disclose the amount of audit fee. We obtained 126 firm year samples for 2012 and 2013.

5. Empirical Result

- The Association between Negative Abnormal Audit Fees and Audit QualityTable 8 shows that the coefficient of ABNFEE is negative significant (-0.149, p = 0.035), indicating that the effect of abnormal audit fees on absolute discretionary accruals is significant negative for firms with negative abnormal fee (ABNFEE < 0). This suggests that negative abnormal audit fees have significant positive impact on audit quality for client firms with negative abnormal audit fees. It means auditors are able to provide an appropriate level of audit quality even when audit fees are below the normal level. Auditors have lower incentives to compromise their independence. Moreover, these results imply that low audit fee rates are not necessarily compensated through a reduction in audit effort. ABAFEE is negative significantly correlated with ABS_DAC. It shows that the higher the abnormal audit fee, the lower the absolute discretionary accrual. It means the higher the abnormal audit fee, audit quality is increase. It means auditors are able to provide an appropriate level of audit quality even when audit fees are below the normal level. Moreover, these results imply that low audit fee rates are not necessarily compensated through a reduction in audit effort. Auditors have lower incentive to compromise their independence.This findings differ with previous research. Choi et al. (2010) and Kraub et al. (2015) which found that negative abnormal audit fee are not significantly associated with audit quality while Ashtana and Boone (2012) found that negative abnormal audit fee negatively associated with audit quality. But Ashtana and Boone (2012) found that this negative association attenuated after SOX reform. This SOX reform increases the independence of auditors, thereby reducing the bonding between the auditor and the client, and then auditor will not allow discretionary accruals which made by the client. Or in other words it will be lowering negative association between negative abnormal audit fee and audit quality. These results support our findings, in which our research conducted using 2012 and 2013 data. The regulation about mandatory audit firm and audit partner rotation that implemented in Indonesia since 2008 increased audit market competition between BIG4 and second tier audit firm especially for listed company client. With high competitive audit market, it resulted a strong bargaining power of clients in the determination of audit fee and pay fee below normal (negative abnormal audit fees). In the high audit market competition, high risk litigation and strict oversight, abnormal negative fee did not decrease the audit quality, but increase, because the auditor will always maintain their reputation and avoid litigation.The existence of differences in study time, which previous studies done on the long period until the year 2010, for example ashtana from 2000 to 2009, choi from 2000 to 2003 and kraub 2005 to 2010. This research used data of 2012 through 2013. Regulation and supervision of the audit firm recently increase so that audit quality is increase. This led to the result that below normal fee does not degrade the audit quality, but surprisingnya, it increase the audit quality.The Association between Positive Abnormal Audit Fees and Audit QualityThe coefficient of POS_ABNFEE*ABNFEE is significantly positive (0.190, p = 0.015) impact on audit quality and the coefficient of ABNFEE is positively significant (-0.149, p = 0.035). Furthermore, the sum of the coefficients of ABNFEE and POS_ABNFEE*ABNFEE is 0.41 (= -0.149 + 0.190). These results are consistent with our prediction that abnormal audit fees have significant positive impact on audit quality for client with positive abnormal audit fees. The higher the abnormal audit fee, the higher the absolute discretionary accruals or lower audit quality. It means that when the auditor receives unusually high audit fees from a client, the auditor will tolerate the client to engage in opportunistic earnings management thus erode audit quality. Our results imply that abnormally high audit fees can be an important source of economic forces that drive the economic bond between auditors and their client firms. The result for firm with negative abnormal fees is quite increase the audit quality. Our results imply that abnormally high audit fees can be an important source of economic forces that drive the economic bond between auditors and their client firms. This result consistent wih result from research of Choi et al. (2010), Ashtana and Boone (2012) and Kraub et al. (2015).

6. Conclusions and Limitations

- In this research, we analyze the empirical association between abnormal audit fees and audit quality in Indonesia where there is high audit market competition and strong client bargaining power because of regulation on mandatory audit firm rotation. We separate abnormal audit fees into positive and negative components to better capture the different economic effects of the two fee constructs on audit quality. Using a sample of 126 firm-year observations for the period from 2012 to 2013, our empirical results demonstrate that positive abnormal audit fees are negatively associated with audit quality and negative abnormal audit fees are positively associated with audit quality. Our results imply that the audit fee premium is a significant factor in the context of compromised auditor independence due to economic auditor–client bonding. Furthermore, we provide evidence that audit fee discounts could increase audit quality when there is high competitive audit market, high regulation where the auditor need to increase their reputation.There is some limitation of this research. First, our main study approach assumes that discretionary accruals are an appropriate measure of earnings management, and thus, are also inversely related to audit quality. Despite the widely accepted use in prior accounting research, discretionary accruals are often criticized as a noisy proxy for the quality of the audit conducted. Though we consider the effects of performance differences among firms in our estimations, our results might be subject to measurement error rather than a reflection of audit quality. Second, though we compute abnormal audit fees using an audit fee estimation model that appears to be well specified and in line with the results of prior audit fee studies, we cannot rule out the possibility of an unknown degree of model misstatement; i.e., due to endogeneity and correlated omitted variables. In particular, audit fees, non-audit fees and abnormal accruals could be determined by the same underlying process (Antle et al. 2006), or respectively, our audit fee model might not be able to fully capture risk characteristics which are correlated with both audit fees and abnormal accruals. Finally, our sample composition is based on publicly traded Indonesian firms. Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to non-public companies. Future research should consider this limitation and investigate the Indonesian private firm context.This research concluded that the premium audit fee would lead to economic bonding between the auditor and the client, thus lowering the quality of audits. Currently, only 12% of companies in Indonesia which disclose value of audit fee in the financial statements. The implication of these findings is that governments need to force all listed companies to disclose the 2audit fee in the financial statements so that users of financial statements can determine whether there is economic bonding between the client and auditor that can cause low the quality of information in the financial statements.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This research was financially supported by the Directorate General of Higher Education for Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML