-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2016; 6(1): 61-71

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20160601.08

A Case Study with Google Data: Parallels of Doping Regulation in Cycling and Banking Regulation in Finance

1Department of Economics, ESB Business School, Reutlingen, Germany

2Reutlingen Research Institute (RRI), Reutlingen University, Reutlingen, Germany

Correspondence to: Bodo Herzog, Department of Economics, ESB Business School, Reutlingen, Germany.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This article analyses and compares the performance of regulators in the fields of finance and sport, especially cycling. I hypothesize that the courses of crises or scandals is the best time to study the lessons of regulatory response. First, I take into account the differences in both finance and cycling by looking at the nature of the rules and institutions governing the field. Second, I estimate the attention effect on new regulation in response to crises or scandals. The interest of the paper is in the alignment of incentives to prevent regulatory capture and to ensure accountability and enforceability. The paper concludes that the differences hold important lessons that call for the reform of rules and institutions governing finance and cycling alike.

Keywords: Regulation, Finance, Cycling, Scandals, Crises

Cite this paper: Bodo Herzog, A Case Study with Google Data: Parallels of Doping Regulation in Cycling and Banking Regulation in Finance, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 61-71. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20160601.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- This paper explores the similarities between regulation in finance and sport, specifically professional cycling. A former professional cyclist Marcel Wüst once said: "In cycling, as in sports in general, there will be always doping. As in politics and business there will be always bribery." This statement demonstrates two far-reaching assertions. One is that cheating is common in all social systems, and can therefore occur in sports, politics, and business. The second claim is that he sees the existence of such fraudulent practices as a kind of natural law, implying that nothing will ever change. But what role does regulation play to mitigate the downsides of this behaviour, particularly in sports and finance?The disastrous consequences of the global financial crisis of 2007 to 2009 resulted in a new debate on regulation. Of course, like after all severe crises, politicians strived to demonstrate its supremacy during this uncertain time. They follow public mistrust to investment banks, which supposedly create the crisis through the introduction of new products, such as collateralized debt obligations (CDO) and credit default swaps (CDS). Banker’s initial suspicious behaviour is reinforced after multiple accounts of fraud. A prime example is the hedge fund manager Bernard Madoff, who had designed a $50bn Ponzi-Game. In the wake of the financial and economic crisis governments designed and phased-in new laws and institutions to protect ordinary citizens in future. Now, there is the Dood-Frank Act in the United States and on the international level there is Basel III. Furthermore, there are new instruments such as macro-prudential supervision as well as institutions such as the Financial Stability Board. But a simple question remains unanswered: Why do regulations fail?Of course, politics is a part of the game. It is both the game setter and the referee. Hence, there is inherently a conflict of interests in the politics of regulation. In order to understand the regulatory problem in more detail, I intend to study and compare the behaviour in both sports and finance. This is a promising and novel interdisciplinary approach because there are arguably several similarities in the regulation in both fields. This is the first paper that attempts to study this interdisciplinary notion.Currently, there are efforts to establish effective global regulation in finance just as there are initiatives to combat doping in sports. The recent doping scandals, such as the IAAF doping scandal in Russian athletics demonstrate the ongoing problem. In both areas, the flaws in the regulatory approach are well-known and have devastating ramifications. The cycling communities in some countries are dying out due to the large amount of doping scandals. The call for effective doping regulation and tougher penalties together with effective reorganization of institutional structures is sometimes too late. The recent examples in sports demonstrate the parallels to cheating as well as crises in finance. There is no doubt that studying the parallels in both sports and finance might contribute to a better understanding of the underlying problem. This interdisciplinary approach reveals new ideas for tackling potential crises in future.Ultimately, I find two profoundly contrasting regulatory paradigms in finance and cycling. There are underlying differences in both regulatory schemes in respect to the dynamics and politics regarding the response to crises or scandals. How did regulatory differences evolve side by side in such dramatically different directions?One possibility reflects on the shift in paradigm for government intervention in the economy from Keynesian to laissez faire. Regulators and market participants oversaw, however, the inherent risk of this shift. Another answer is the development under the scholarly leadership of George Stigler from the Chicago School of Economics. Stigler and his followers believe that government regulation is restricted by its own constraints. In fact, they argue that regulatory agencies are more likely to be captured by those they were intended to regulate in the first place. While these movements diverged over the issue of regulation, they were extremely influential in finance. They proved less effective in other areas, such as the aviation sector. This leads to the question: How did they evolve in such different directions? Are there parallels between doping regulation in cycling and financial regulation in finance?To answer these questions, I carry out an institutional and regulatory comparison and undertake an econometric assessment with unique Google search data. Section 2 provides a brief literature review together with underlying definitions. The structure of regulation in finance and cycling is compared in section 3. In addition, I focus on international and regulatory bodies in Germany. Germany is an excellent case study because the past doping scandals had devastating consequences, particularly in professional cycling. Germany is also a leading player in global trade and finance, making it a worthy candidate for adequate comparison in both fields. In section 4, I analyse the relevant Google data. The paper addresses the problem whether or not regulation is affected by scandals or crises. Hence, I estimate and forecast several models in order to better understand the effectiveness of certain policy response. At the end, I develop policy recommendations based on the idea and design of regulation in the aviation sector. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

- Several experts argue that the flaws of the regulatory system prior to crises or scandals are a root cause of the mess in the end. In fact, a major flaw in finance is the mere focus on microprudential regulation [1,2]. Microprudential supervision aims to prevent the failure of individual institutions and does not see the system-wide aspects. Consequently, to mitigate systemic risks, we need a macroprudential approach that recognizes the general equilibrium effects, i.e. feedback loops, interdependencies, bubbles, and so on [3]. Interestingly, despite the on-going regulatory debates in both finance and sports, there is almost no comprehensive regulatory theory that identifies the optimal degree of regulation [4]. An exception is the approach discussed in [5]. He provides a general theory that discusses the regulatory trade-off in different fields of market environments. Hence, this approach provides insights to policy-makers in general.The word ‘regulation’ comes from the Latin word regula (i.e. straight edge, a guide, scale, usually) and regere (i.e. straighten, divert, prevail). Thus, it refers on one hand to the process of control. On the other hand, it implies the output of an ordered state. However, economists utilize the term regulation in a broad context. They include both the regulation of the overall economic and social system [6]. For instance, the ‘Federal Agency for Civic Education’ understands regulation as a ‘direct intervention by the government in market operations and an influencing behaviour of companies by regulation to achieve specific public interest for standing objectives.’ In literature, we differentiate between two types of regulation: either preventive, designed to mitigate damage in general, or protective, designed to mitigate damage in advance.The justifications of public interventions are potential market failures, such as the monopolistic abuse of power or negative externalities [7]. Public regulation is targeting the preservation of mutual trust that stabilizes a dynamic market in the end. Apart from the government, non-governmental institutions take regulatory tasks in a globalized economy, such as independent authorities or investor-state dispute settlements [4, 8]. For decades, regulatory policy has consisted of several stakeholders. There are different national and increasingly international, or even global boards. Indeed, effective national measures can easily be circumvented on an international level, i.e. regulatory-arbitrage [9]. Consequently, regulatory measures ought to be agreed on and implemented at a global level. A further problem is the existence of vested-interest groups in the regulatory debate. Seminal papers by [10] and [5] demonstrate that specific environments require specific regulatory response. This finding is in contrast to the previous approach by [11]. The literature on bank regulation has a long tradition in finance. Therefore, I briefly review this literature in more detail. The first and most important finding of a market failure in finance is the study by [12]. They argue for deposit insurance and provide a solution to bank runs. Another aspect studied in literature is solvency regulation. They argue for the need of capital buffers [13, 14]. Furthermore, [15] argues that banks possess better information regarding their own risks, meaning that regulators will never be effective enough to regulate a dynamic market. I intend to show that an interdisciplinary approach might provide effective answers to regulation even in dynamic and complex environments.

3. Regulatory Framework

- The issue of doping has been a frequent subject for quite some time in sports across all the board. In the next subsection, I elaborate the institutional structure of anti-doping regulation in cycling. Afterwards, I study bank regulation in finance in subsection 3.2.

3.1. Cycling

- At the top of the global anti-doping campaign is the so-called ‘World Anti-Doping Agency’ (WADA). WADA is organized as a foundation under Swiss law at the Anti-Doping Organization by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1999. In accordance with article 4 of the Foundation's Statute it pursues the objective ‘to promote and coordinate the fight against doping in sport in all its forms’ [16]. The independent WADA equally receives its funding from numerous sports organizations and governments. Hence, the organization retains its independence since it is not bound by the instructions of donors but instead merely committed to their own rule of law.The activities of WADA include, among other things, the dissemination of sport ethics of a doping-free sport, the research and development of new testing methods and the coordination as well as execution of doping tests’ during sporting events and training periods. Furthermore, WADA defines new standards for doping tests and approves the standards in accredited laboratories [17]. The so-called WADA Code was adopted by more than 51 governments and associations at the Copenhagen World Conference on Anti-Doping on 5 March 2003. Since then, it is the main framework to combat doping. However, the enforcement of the WADA Code is not part of the treaty. In fact, the enforcement still pertains to the sovereignty of national organizations.In Germany, the WADA Anti-Doping Code was adopted in 2004 by the national authority, specifically the ‘National Anti-Doping Agency’ (NADA). Apart from the harmonization of doping controls, the national adaption of the Anti-Doping Code targets a better implementation and enforcement of regulatory measures. They even developed an independent medical board, in order to manage exceptions such as special medication issues for ill sportswomen or sportsmen. In addition, the ‘German Olympic Sports Confederation’ (DOSB) founded in 2006, and the related association implemented new strategies in cycling. On the international level there is the ‘Union Cycliste Internationale’ (UCI) and at the German level there is the ‘German Cycling Federation’ (BDR). All organizations have programs to combat doping and continuously improve the existing measures [18]. In regards to the hierarchy of these institutions the BDR regulates all matters at the national level. The BDR consists of 17 regional cycling associations with more than 2,500 affiliated clubs. However, the approvals of professional cyclists remain in the responsibility of the UCI. Here you can already detect the overlap and interaction of national and international regulation even in sports. The national level has limited responsibility in respect of anti-doping standards and control, while the international level has imperfect control over national procedures and the enforcement of anti-doping laws. The most significant drawback however, despite the independence of institutions, is the voluntary nature. Most international anti-doping procedures are self-designed. There is limited accountability of these procedures in respect to public law. This is an evident disadvantage in almost all scandals.Next, let me describe the so-called doping test procedure. The two anti-doping codes of WADA and NADA are similar in their content. They have the same list of criminal offenses and an open list of prohibited drugs. In this context, the two codes reveal the negative definition of the concept of doping. In article 1 of NADA, doping is defined ‘as the violations to one or more anti-doping rules’. But in general, the definition of doping is much broader than the mere detection of a performance-enhancing substance in an athlete's body. Even the possession and dissemination of banned substances, misconduct during sampling, or breaches of reporting behaviour will be punished.Accordingly, all professional athletes are obliged to provide details of their location and training times. In addition, special groups of athletes, such as A- (B-) professional athletes have to inform the NADA if they stay away for longer than 24h (72h) of their common habitual residence (article 5.5 NADA). The central idea of the doping control process is to have a continuous and unpredictable procedure. In general, they distinguish between training and competition controls (article 5.1 NADA). Competition testing is basically the responsibility of NADA in Germany. But the procedure is carried out by eligible organizers of events. In order to investigate the blood sample, the organizers transfer it to NADA. The selection of athletes is described in article 5.5 of the NADA code. In practice, there is a lottery-like procedure with a target selection of athletes according to performance. Each doping inspection takes two samples from an athlete. If sample A is positive and it is not a dispensation, then a procedural defect in the subsequent examination could still be detected. Hence, sample B is examined. If sample B is positive as well, then measures against the athlete will be initiated. In Germany, there are two recognized WADA test labs in Kreischa and Cologne. However, the doping laboratories face several challenges. First of all, there is a rapid evolution of new doping substances, in particular, blood doping and newly designed gene-doping. Secondly, there is a certain time delay and lack of doping analytics in general [17, 19]. The consequences in regards to doping are clearly defined. Usually, the athlete is disqualified and suspended from future competitions. Furthermore, past victories, achieved via the usage of doping, are renounced from the athlete. Even a lifetime ban is possible in the case of a second offense. Despite these anti-doping rules in cycling, and in sports in general, it is still a recurring problem. In an effort to prevent this, in 2015, the German government strengthened the anti-doping law significantly. Now athletes and dealers of doping substances even face prison time. Although WADA and NADA have pre-emptive procedures, such as customized information and education for young athletes, it is evident that this toolbox is rather ineffective and has thus far not really prevented doping scandals. They have also failed to strengthen the self-responsibility and, self-esteem that could prevent the tendency of doping [20].

3.2. Finance

- The goals of financial regulation are to protect creditors against opportunistic behaviour of financial intermediaries as well as to stabilize the interconnected financial system. To achieve these goals, the public sector has the ability to regulate and intervene at various levels. So the financial intermediation system is subject to many different regulatory rules and bodies. To compare the doping control system with financial regulation, I study the structural elements of financial regulation next.Regarding the measures, I distinguish between preventive and protective measures again. Furthermore, in finance I differentiate between qualitative and quantitative measures. While quantitative rules are based on verifiable rules, qualitative regulation consists of general standards, such as best practice [19].The overall regulatory structure in finance consists of special supervisory bodies at the national, European and international level as well as special responsibilities for central banks [21]. Depending on the country, the responsibility is either delegated to several authorities, such as a Banking, Securities and Exchange Commission, etc., or a central authority. The latter approach of financial supervision is currently on the forefront in several countries. Germany implemented a central financial supervisory authority on 1 May 2002. The three previous federal supervisory authorities for Banking, Insurance and Securities trading were merged into the ‘Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht’ (BaFin). Now, the BaFin has all responsibilities and exercises financial supervision for all operating financial institutions independently according to §6 KGW (German Credit Law). The organizational autonomy of the BaFin is, however, less pronounced. It does not have its own statute and authority without approval and permission by the Federal Minister of Finance. In addition, from a human resources perspective, the working and payment conditions are limited by the law for civil servants [20].The German Banking Act contains provisions on cooperation between the BaFin and the German central bank (Bundesbank). §7 KGW state that the central bank has ongoing responsibility over private banks. However, decisions about individual banks or the adoption of administrative acts is still the sole responsibility of the BaFin [20]. In terms of sanctions, the BaFin has the sole power. It can withdraw the bank license which happens typically in serious cases of mismanagement.Along with the ongoing financial globalization, there are continuous efforts to cross-border cooperation and harmonization of regulatory standards in Europe. A variety of European and international organizations have been established in recent years [7]. The most important are the, European Banking Authority (EBA), the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the International Organization of Securities Commission (IOSCO), and the Financial Stability Board (FSB). However, global rules are not binding and thus regulatory-arbitrage still takes place. In finance, national authorities still have the main power in all regulatory matters.

4. Do Scandals Change Regulation?

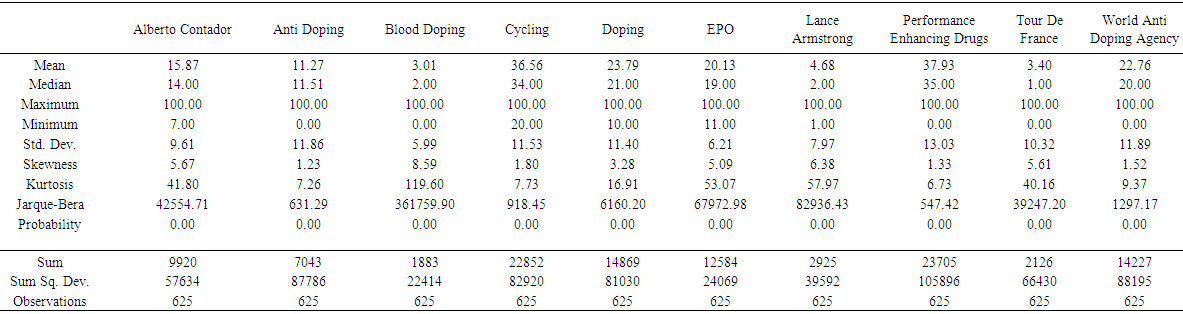

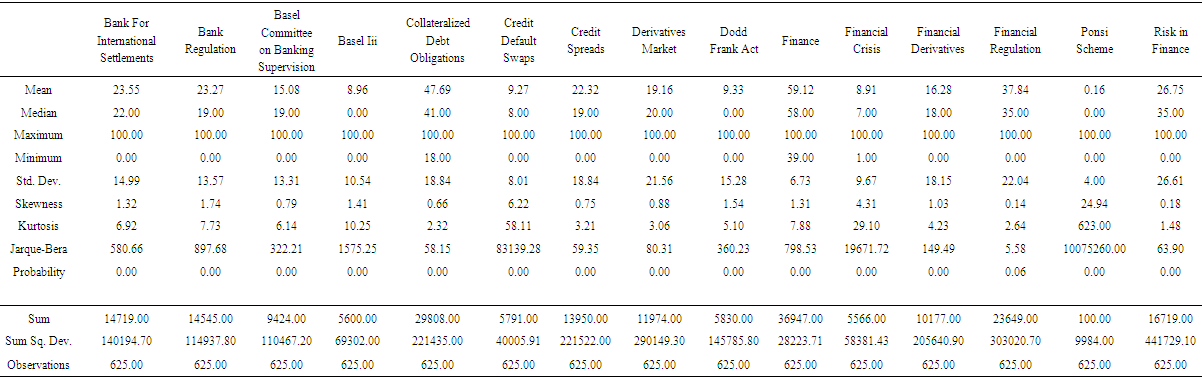

- In this section, I study the relationship of regulation in cycling and finance. I use Google search data which is available from Google.com. According to [21] Google data are the only direct measure of attention today. In other words, if you gather a time-series from Google, for instance the word ‘Doping’, you get information when and how many people have been interested in this word. I gathered 25 weekly Google time-series from 2004 to 2015. This timeframe corresponds to approximately 625 weeks for each time-series. The time-series are collected by expressions, such as ‘Anti Doping’, ‘EPO’, ‘Lance Armstrong’ or ‘Bank Regulation’, ‘Collateralized Debt Obligations’, ‘Basel III’ and so on. These terms measure the attention of different notions in cycling and finance over time.

4.1. Method

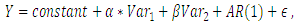

- In the next step I study the statistical properties as well as the model forecast. The question is twofold: i) what explains the attention that is directed to ‘Anti Doping’ or ‘Bank Regulation’? ii) what changes or enhances regulation in both fields: risk factors or scandals? I estimate a simple time-series regression model

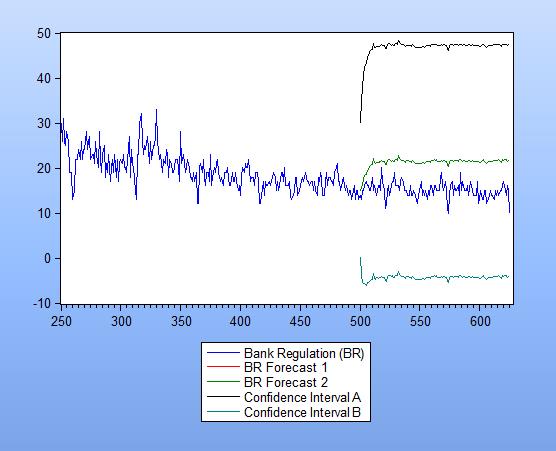

| (1) |

| (2) |

4.2. Results

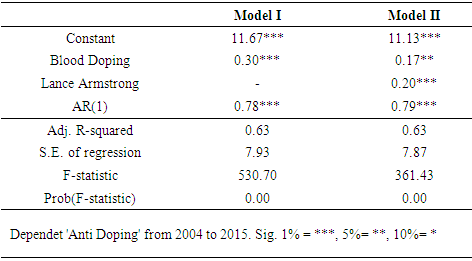

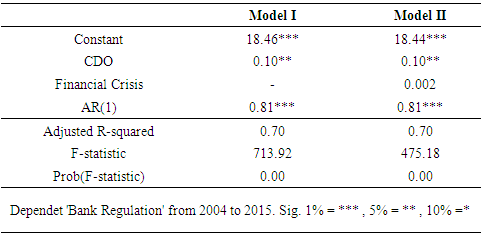

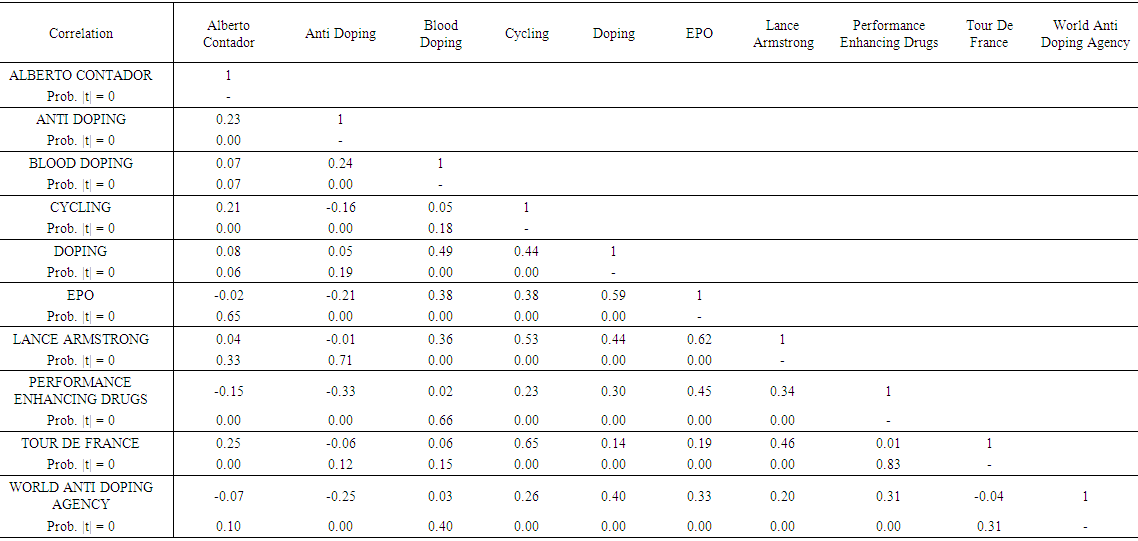

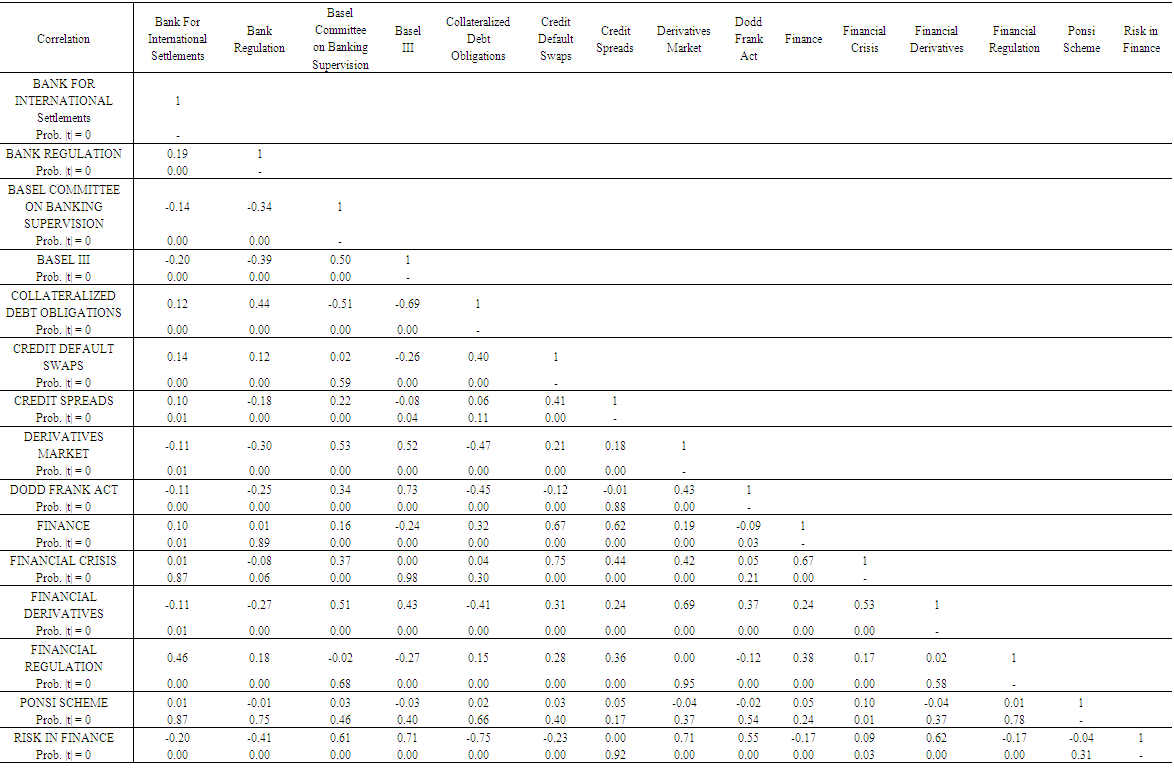

- Now, I begin with the econometric assessment. I attempt to explain the development of the variable ‘Anti Doping’ in cycling and ‘Bank Regulation’ in finance. In cycling I use two independent variables: first ‘Blood Doping’. Firstly, I study the impact on the attention of ‘Anti Doping’ with Google searches of the term ‘Blood Doping’. The correlation is 0.24 and positive as well as significant. The second variable is ‘Lance Armstrong’. This variable is a measure of the greatest doping scandal in cycling ever. Lance Armstrong has won the Tour de France 7 times but it turned out that he had used doping techniques to obtain this unnatural success. The statistical correlation of ‘Anti Doping’ and ‘Lance Armstrong’ is almost zero and not significant.Table 1 illustrates the results of Model I and Model II. The regression reveals two important findings: Both independent variables explain the dependent variable ‘Anti Doping’ sufficiently and significantly. Second, the adjusted R-square and F-test denote a good quality of both models. However, as I demonstrate next, the predictive power of Model I and Model II are different.

|

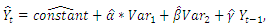

| Figure 1. Forecast Model I |

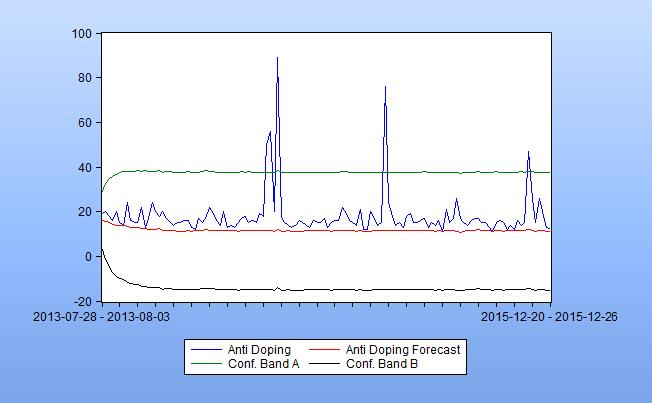

| Figure 2. Summary of Forecasting Model I and Model II, 2013-2015 |

|

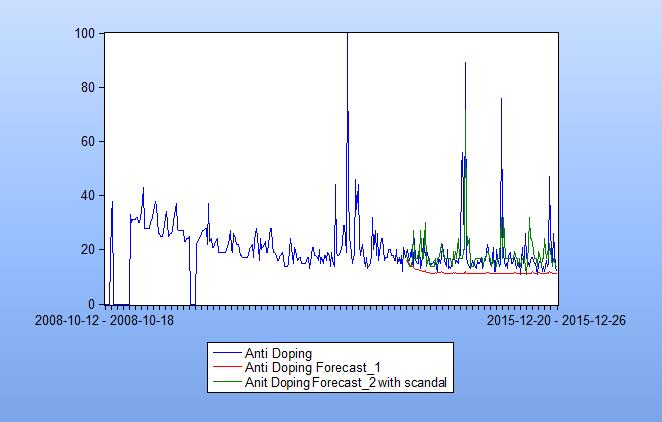

| Figure 3. Summary Model I and Model, 2013-2015 |

4.3. Discussion and Recommendations

- Nobel laureates George Akerlof, Robert Shiller and others have criticized traditional economics for its failure to understand the importance of animal spirits and thus regulation in an economy. They argue that economic theory has failed to acknowledge that economic crises ‘are mainly caused by changing thought patterns’. Similarly, Ken Rogoff argues that more transparency is required as it is one of the most important roles of markets. However, on the contrary, there is a culture of non-transparency particularly in finance.I propose that the transparent and global approach in aviation regulation is a good benchmark for the future of regulation. The major elements of regulation in aviation are: i) it is dynamic. Specifically in that, the regulation adjusts immediately to new problems and challenges; ii) it is independent. Hence, the regulation is fully transparent and thus independent from politics and vested interests; and iii) it is truly international, i.e. all countries have to follow the rules and regulations. Jack Welch called this a culture of ‘boundarylessness’. I think it is this idea worth implementing in regulation. In simple words, one must respect the limits of one’s own responsibility while being mindful of the impact and need to share across functions and organizations. In fact, we have lived through the most dramatic economic event of our generation and, while there is some normalcy to this economic recovery, the root causes are by no means solved entirely. Through the prism of my study, it appears that regulation in finance and sports have evolved in two different directions. The world of finance is characterized by an almost pathological antipathy to regulation while the regulation in cycling has transformed after big scandals. The approach of change is through trial and error. Moreover, that is the key element and driver of regulation in the aviation sector. An airplane crash or a technical problem during a flight always leads to a rigorous study and finally better rules and procedures to avoid this in the future. In aviation business, a new engine must first be tested for years before it is approved and accepted. This regulatory philosophy is also recommendable for new financial products. Overall, the regulatory approach in the field of aviation is based on trial and error and thus more efficient in a dynamic environment.This study illustrates several parallels and differences between the regulatory structures of both cycling and finance. It begins with the need and justification of regulation in both sectors. It is mainly due to market failures. However, in cycling as well as in finance the professionals are usually ahead of the public regulator. In cycling it is due to continuous medical progress and a lag in the testing procedures. In financial markets it is similar. Here, we have continuous financial innovation. Thus professionals distribute potential tail risks to the society. In addition, financial products become more and more complex, and thus it is hardly possible to detect all risks in advance especially in a static rule-based approach as it is today. Indeed, experts with knowledge in doping or financial engineering do not get caught rather benefit. Although this is a terrifying conclusion, it can be changed by effective, and not necessarily new, regulation.There is anecdotal evidence that existing control procedures and incentives are far too weak in sports and finance. For instance, effective banking supervision requires experts but the BaFin cannot attract experts by regular civil service salaries [22]. Another problem is the parallelism of regulatory institutions and stakeholders. In the case of cycling there are several sports’ federations that have overlapping powers and sometimes shared responsibilities. This regulatory structure is inefficient. In the end, the anti-doping institution neither enforces the law effectively nor takes responsibility of effective control.Similar conflicts arise in financial markets. The central bank partly has contradicting objectives: financial stability and price stability. But price-stability may be contrary to financial stability which requires lender of last resort policy and thus creates moral hazard. In the end, this leads to further risk taking and instability in the financial and economic system. In this context, a long-standing question pops up: how does one control the controllers? The best answer to this problem is a look to the regulatory approach in the aviation sector again.

5. Conclusions

- All in all, this paper demonstrates an interdisciplinary study of regulatory developments in finance and cycling. There is indubitably a need for change. Regulators in both systems can learn from each other and the best benchmark is probably the dynamic, independent and international approach in the aviation sector which is characterized by stringent regulation as well as by trial and error.It remains an open question whether cross-fertilization of regulation is successful and whether politics will implement some of the ideas. But the frequency of past crises and scandals is motivation for change. This paper raises a host of questions that deserve further examination. Do we need a greater convergence in global regulatory regimes? Do we need a new paradigm for understanding global regulation? The innovative and interdisciplinary answer provided in this paper is a good vantage point for effective progress and further research in future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I am grateful for support by the RRI Reutlingen Research Institute. Moreover, I thank Laura Wanzl for support in this research project. Moreover, I thank Lena Popp and in particular Chiara Fritsch for an excellent editing of this paper. I wish to acknowledge the two anonymous referees for the comments and feedback.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML