-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2016; 6(1): 27-31

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20160601.04

Analysis of Chinese Student Values and Implications for the Global Economy

1Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

2Dixie State University, St George, Utah, USA

Correspondence to: Verl Anderson, Dixie State University, St George, Utah, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Although the importance of understanding the culture and values of other nations has been well documented for many years, much of the research is aging and needs to be updated to include the values and beliefs of tomorrow’s leaders and managers. This paper presents findings from a values study with Chinese university business students, and provides valuable insights with regards to the values of tomorrow’s Chinese leaders and employees.

Keywords: Chinese economic impact, Chinese values, Values research, Chinese university students

Cite this paper: Ziying Cao, Verl Anderson, Analysis of Chinese Student Values and Implications for the Global Economy, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 27-31. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20160601.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In a world that has become increasingly global, competitive, and even chaotic the ability to relate to others across cultures has become a requisite skill for those who wish to be successful in international competition and collaboration (Steers, Nardon & Sanchez-Runde, 2013). Values, core beliefs, and paradigms about management are profoundly different from culture to culture and even among people within the same cultures (Covey, 2004). As business leaders struggle to manage the international corporation across cultures, understanding the key differences between the underlying normative beliefs of those with whom they work can profoundly impact their ability to win the trust, commitment, and engagement of their employees. Values that were held in high esteem in an older generation my not be the primary values of the younger generation. Understanding the nuances of different cultures can greatly enhance the ability to successfully impliment corporate strategies in a global environment. Whereas the failure to grasp key concepts in a culture can profoundly negatively affect the success a corporation can have in the introduction of products and services into a new environment.Chinese values have been studied for a half century by highly regarded scholars (Hofstede, 2001), but limited research has been done to examine the values of the upcoming generation who will be the employees, managers, and leaders in the Chinese business world in the next few decades (Zupan, 2015). Understanding of these values can be a critical element in successful business dealings (Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 2012). Thus, examining the values of future business professionals has great worth, not only for Chinese managers, but also for others doing business with Chinese companies.Although studies of differences in organizational culture have been conducted at the macro-level by several other scholars, we propose that this study adds important incremental insights about the beliefs, attitudes, and values that exist among a key group of individuals who will soon become tomorrow’s knowledge workers in the international business community. The purpose of this paper is to evaluatekey values of Chinese university students as found in an elective survey and present insights about the attitudes and core beliefs of business students in China. Further, the purpose of this paper is to compare similarities and differences of the young men and women in China that make up this cohort group and to suggest implications about those values for those who will employ them in organizations and collaborate with them in an increasingly complex world. By understanding these differences and similarities of the new generation of youth, leaders in businesses can maximize their effectiveness in the creation of their strategies, protocols, systems, marketing, and corporate structures in this global economy.

2. Main Body

- Studies of the varying cultures across the world have been a subject of notable interest for decades (Hofstede, 1987; Kluchohn, 1961; Hall, 2000). Business leaders have acknowledged the reality that differences in normative values and assumptions impact how people think, how people work as individuals and members of groups, and the most effective ways to achieve organizational goals while meeting individual and societal needs (Trompenaars, 2012). Over the past 63 years, 14 major research studies have been conducted in regards to cultural values of individuals within nations. The most well-known of these studies was conducted from 1967-73 by the world’s foremost cross-culture expert, Geert Hodfstede. This study included a survey administered to 117,000 IBM workers across 40 countries. He defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the memers of one group or category of people from another.” (Hofstede, 1997: p.5). Hofstede identified four dimensions that he claimed summarized different cultures—power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism versus collectivism, and masculinity versus feminity. Bond (2010, 2004, 1988) researched the Chinese Value Survey, added another dimension, and named the fifth dimension “Confucian Work Dynamism”, which is associated with Confucian values and the teachings of Confucius. Hofstede, in his later work,stated this Confucian dynamism captures attitudes toward time, persistence, ordering by status, protection of face, respect for tradition, and reciprocation of gifts and favors (2001, 1988). A sixth dimension on culture was added by Minkov (2007) as he developed a World Values Survey. This value was the degree to which members of a society try to control their desires and impulses. It also explored Long-verses Short-Term Orientation (LTO) captured values gathered from the World Values Survey.Hofstede and Bond (1988) noted that traditional values of Confucianism were being modified by individuals focusing on pursuing economic prosperity. They reported findings of deemphasizing the importance of protecting face; respect for tradition; reciprocation of greetings, favors, and gifts; and a reliance on personal steadiness and stability. These traditional factors have been viewed as in conflict with the need for economic initiative, risk-taking, and entrepreneurship which have been key to China’s economic growth (Hofstede & Bond, 1988, p. 9-18).These changing of values have been influenced with globalization, advances in communication technologies, available transportation, the increase of presence of global corporations (e.g. Microsoft, Apple, Coca Cola, McDonalds, Levi Strauss, etc.), and products and operations that can be found world wide (e.g. iPads, iPods, MTV). All these are creating conditions for the merging of cultures (Inglehart, 2000; Bian, 2002).Because understanding values can be a critical element in successful business dealings (Trompenaars, 2012), examining the values of future business professionals has value not only for Chinese managers but also for others doing business with Chinese companies.

3. Methodology

- A survey instrument was constructed from identified values from eleven research studies (Kluchohn, 1961; Hofstede, 1997; Hall, 2000; Trompenaars, 2012; Schwartz, 1994; House, 2004; Steers, 2013; Bond, 1988; Hitlin, 2004; Yang, 1990;). In addition, included in the survey instrument were values from the recent announcement by Chinese President Xi (Xi, 2015), of twelve values or virtues that he advocated be adopted by Chinese society. The purpose of this announcement was to encourage youth to embrace those core values in the quest for long-term Chinese economic prosperity. The values emphasized by Xi bridged traditional Confucian values of harmony and equality but also emphasized patriotism, being prosperous and strong, being just in dealings with others, being governed by law, and being diligent in one’s work.A focus group of Chinese university students was then conducted to identify additional values deemed important to Chinese youth and that input was incorporated into the list of values created for this study. Those additional values included the preeminence of the national interest, a tranquil moral conscience, physical fitness, healthy life, fair competition, integrity, guanxi, quality of life, happy children, economic prosperity, equality between husband and wife, love and respect of my spouse’s family, access to health care, and a sense of destiny. A total of 110 values were included in the final survey instrument, narrowed from an original listing of 143 values from scholar studies. This survey was administered at a Tier 1 university and a Tier III university in twomajor cities in Central China. Anonymously, participants in the survey were asked to identify the relative importance of each factor on a five-point Likert-type scale with a score of one meaning that the value factor was Not Important and a score of five meaning that the factor was Extremely Important. The survey instrument was divided into five different categories of the value system (Country and World, Personal Quality, Career, Family and Relations, and Life and Religion). Within each category, participants were then asked to identify the two most important values to them personally in each category. Respondents were also asked to indicate their gender.

4. Findings and Insights

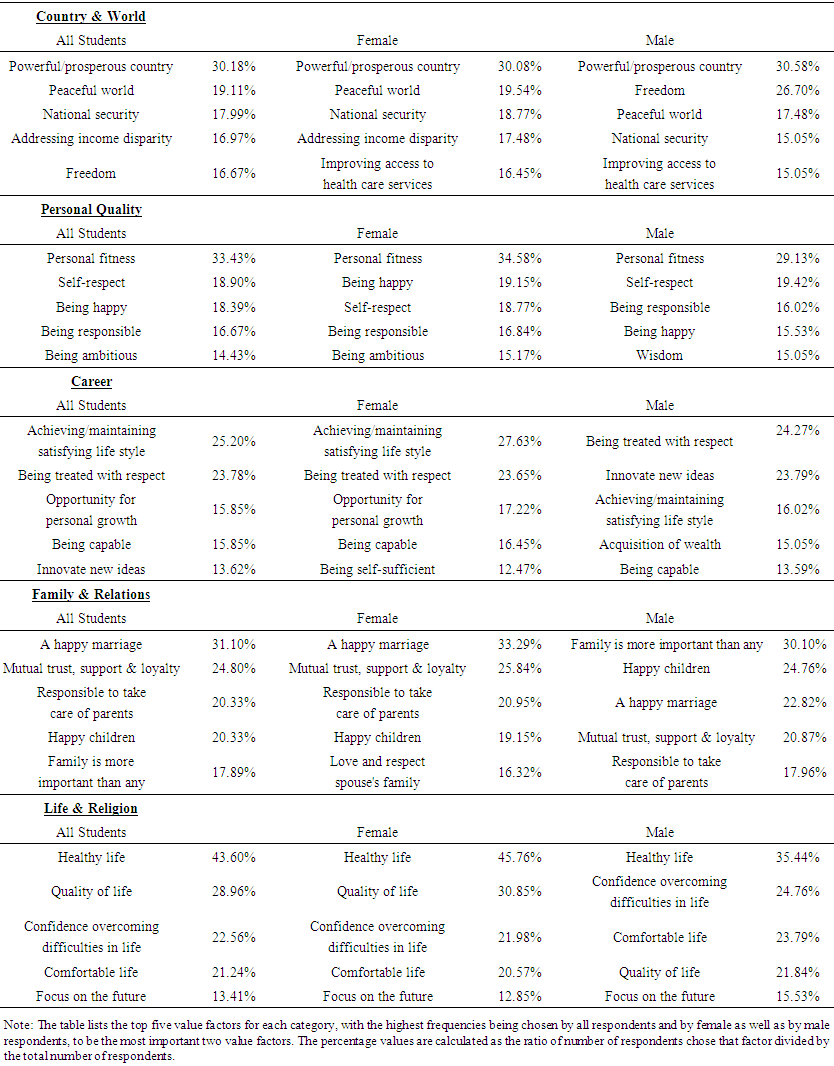

- A total of 1,032 surveys were administered, of which 984 were complete and usable for the study. Mean rating scores of all 110 value factors, range from 4.84 for the factor National Security in the Country and World category to 2.64 for the factor Relationship with God in the category of Life and Religion. These responses are consistent with Chinese historical and cultural characteristics. Confucianism views a secure and stable society as essential to maintain order and harmony, which would account for the high factor level of National Security. In regards to the low factor level of the relationship with God, the historically dominating influences of Communism discouraged commitment to religion, which would lead to that factor not as so important as other survey items. For each category, Table 1 lists the top five value factors chosen by the respondents in each of the five major sections of the survey—listed by combined total, then by gender.

| Table 1. Top five selected most important value factors of each category |

5. Contributions of this Paper

- Much has been written about differences in the cultures of countries, including many articles unique to the Chinese culture. This paper makes several significant contributions to the academic literature.1) Most of the studies of Chinese culture are dated. Relevant information in these prior papers has changed somewhat with the rising generation of youth in China. This paper provides current information for tomorrow’s business leaders.2) This study has combined research from scholars from the past 50 years into one current survey instrument.3) This study has gathered information of both males and females in the Chinese university student community, offering insights of differences and similarities between the genders.4) This paper combines the assessment of traditional Chinese cultural values, with Confucianism, and the current values of today’s youth.

6. Conclusions

- China has a new role as the world’s largest economy. It is essential that the global business environment understand and adapt to the values held high by future Chinese leaders and managers of tomorrow. In a world that is increasingly smaller and interconnected, due to travel, Internet, communications, and blending of cultures, the understanding of the influence of values is paramount to success in the global economy. This group is likely to be representative of many business employees and future business leaders in China over the next several decades, even though their values may change somewhat over time.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML