Yusuf Sulaimon Aremu 1, Adedina Lawrence Olusoga 2, Egbekule S. O. 1

1Department of General Studies, Moshood Abiola Polytechnic, Abeokuta, Nigeria

2Department of Business Administration, Moshood Abiola Polytechnic, Abeokuta, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Yusuf Sulaimon Aremu , Department of General Studies, Moshood Abiola Polytechnic, Abeokuta, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The study examined ‘CBN Cashless Policy: Does it financially Include Micro-Entrepreneurs in the Informal Sector? Empirical Verity from Ogun-State, Nigeria’. Its broad objective was to determine to what extent the micro-entrepreneurs in the informal sector are financially carried along with the ongoing CBN cashless economy policy. More so, to determine the possible implication of failure to carry the Subsector along on the achievement of the objectives set forth by the policy. The inferential survey research design was used. The study revealed that the CBN cashless economic policy is lopsided in its implementation; it fails to carry the teeming population of micro-entrepreneurs in informal sector along. Consequently, this is detrimental and counterproductive to the achievement of cashless economic objectives. The research work proffers the primary efforts, issues of national concern and the secondary efforts, issues of direct concern to CBN as the way forward to make the objectives of the cashless economy policy achievable.

Keywords:

Cashless Policy, Financial Inclusion, Micro Entrepreneurs, Informal Sector, Yusuf’s Cashless Elasticity of Financial Inclusion Model

Cite this paper: Yusuf Sulaimon Aremu , Adedina Lawrence Olusoga , Egbekule S. O. , CBN Cashless Policy: Does it financially Include Micro-Entrepreneurs in Informal Sector? Empirical Verity from Ogun-State, Nigeria, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 5 No. 6, 2015, pp. 595-608. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20150506.05.

1. Introduction

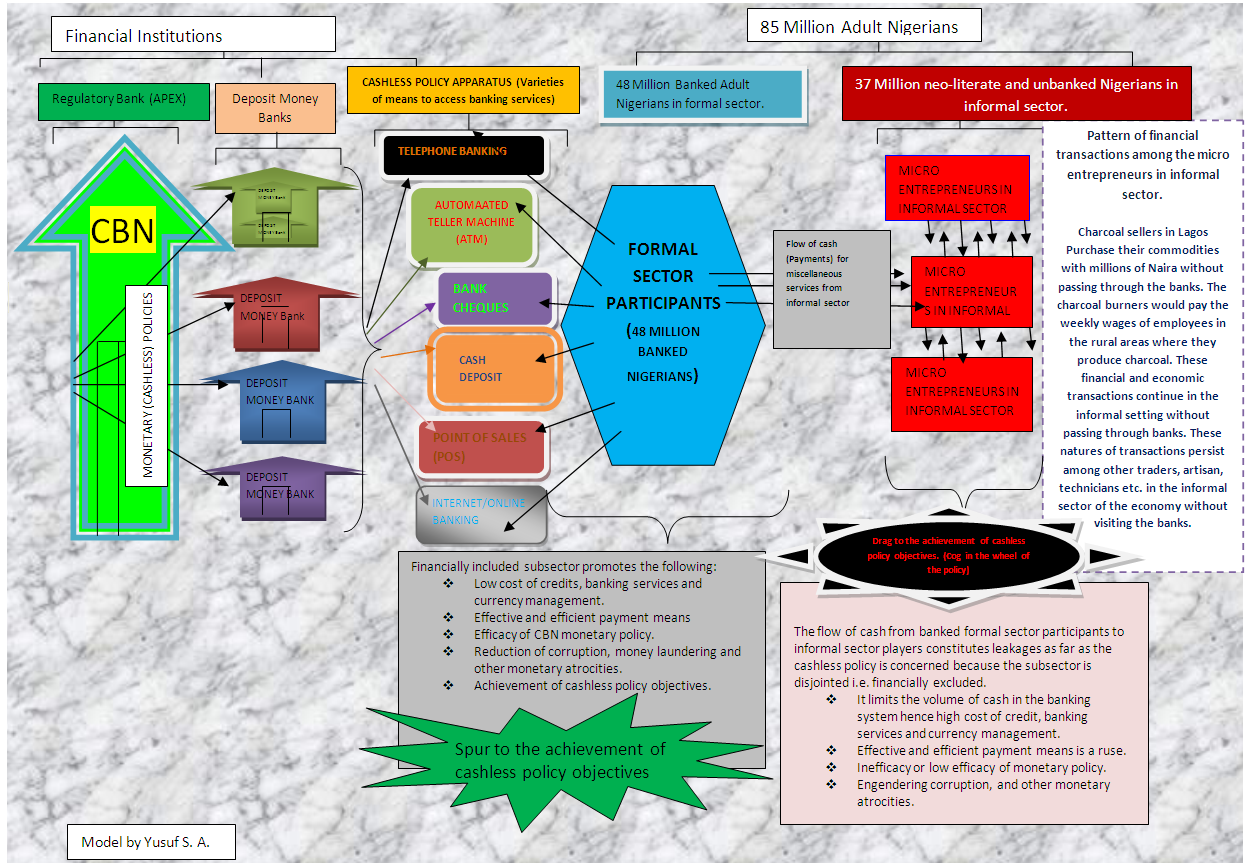

The paradigm shift of cash-economy to cashless economy is a developmental experience to the monetary system of a developing nation like Nigeria. The quest to improve the monetary system towards bridging the gap between Nigeria as a developing economy and the advanced economies in order to facilitate the accomplishment of the global economic target of 20:2020 vision makes the cashless policy imperative in one hand. On the other hand, a careful consideration of the three key objectives of the policy (CBN, 2012) [1]: development and modernization of the payment system; reduction in the cost of banking services and to drive the financial inclusion by the provision of efficient transaction options and greater reach; to make the monetary policy more efficacious reveals that these policy thrusts are virtues that cannot be overemphasized for the economic growth and development of the nation. But, the workability of the policy roost majorly on the use of information communication technology based network in discharging the financial services by the banking system and the sundry. In other words, in a bid to launch the economy to the cashless status, drastic reduction in the use of cash for transaction purposes calls for intensive use of electronic and internet base medium like ATM, EFT/POS, electronic wallet, mobile and telephone banking etc. Given the demographic features of Nigerians where about 35,000,000 adult Nigerians are non-literate (EFA report, cited by Laide A., 2013) [2]. And, 17,261,753 Nigerians are micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector (National MSME Collaborative Survey, 2010) [3]. It is important to emphasize that 36.9 million Nigerian adults out of 93 million of the Nigeria adult population are not banked (EFInA, 2014) [4]. The chunk of this segment of the economy is micro entrepreneurs like barbers, carpenters, iron benders, hairdressers, Plumbers, fashion designers, transporters, retailers Sachet water retailers that operate in rural areas and slum part of the urban area where they have little or no access to electricity and internet facility (Bakare, 2009) [5]. In fact, any true developmental monetary policy adopted must not fail to carry this Subsector along if the achievement of the objectives of this so called cashless economic policy doesn’t want to be a subterfuge. Going by the provision of the policy in its bid to achieve the set objectives, it is implicit that this subsector of the economy is yet to be well integrated into this new developmental financial policy as the peculiar programmes recognizing their socio-economic attributes that could capture their financial and economic activities are not explicitly embodied in the policy. Failure of the CBN to develop a well calculated and planned effort to carry along the micro segment of SMEs might be counterproductive in achieving a well rounded development in the monetary/financial sector through the highly hyped cashless economy policy. Because so many highly glorified adopted policies have failed to yield results due to the structural problem like this.The reason why the subsector could constitute a drag to the achievement of the objectives of the cashless policy is not farfetched. The policy framework put in place and the policy brief recommended as the steps that CBN and industry should take to facilitate the success of the cashless economy by bringing over 46% financially excluded Nigerians into the formal sector (Onajite and Nnene, 2012) [6]. The step put in place is adjudged inadequate by this study because it failed to recognize and address the peculiarity of the micro entrepreneurs in Nigeria. The majority of the micro-entrepreneurs are not banked hence they operate outside the jurisdiction of the banking system. Meanwhile, the participants in the formal sector depend majorly on micro-entrepreneurs for their miscellaneous economic activities in the informal sector (Yusuf, 2014) [7]. Consequently, the flow of money to this Subsector of the economy would constitute a leakage as far as the cashless economy policy is concerned because the microeconomic operators carry out their economic transactions without engaging bank in the process in fact, most of them do not operate bank accounts (EFInA, 2014) [4].Against this backdrop, this research work aims to determine what extent the micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector are included in the cashless economy policy. More so, it aims to develop a theoretical framework and a model with the view of determining the effect of financial exclusion of this Subsector on the achievement of the objectives set by the policy; to proffer policy prescriptions that would make the Subsector serve as spur to the achievement of the cashless policy objective amidst the peculiar socioeconomic attributes of this Subsector.Furthermore, the relentless effort of the researchers on this piece of paper is justified on the ground that it would serve as an improvement on the scanty extant related studies that are qualitative in dimension. This research work would get its objectives achieved by empirically examining the discourse in Ogun-state, the state with an estimated population of 471,772 micro entrepreneurs (National MSME Survey, 2010) [3]. One of the first five states that adopted the policy immediately after the pilot in Lagos state on 1st October, 2013. In order to achieve the aforementioned objectives of the research work, apart from this introductory section, the second section reviewed concepts, relevant related theory and empirical literatures. The third section presents the Methodology, theoretical framework and the models of the study. Section four carried out empirical analysis of the study. Finally, section five presents the summary of findings, conclusion and offers valuable policy recommendations.

2. Review of Literatures

Conceptually, cashless economy entails a drastic reduction in the handling of cash for transaction purposes, but rely more on the sending of an electronic signal to banks for the payment and receipt of money on ones’ behalf in the process of exchange. It is not to say that the use of cash will be eradicated, but will be limited to the barest minimum for carrying out financial transactions. Basel Committee (1998) [8] found the concept esoteric because it mixes technological and economic features. It doesn’t restrict the banking services (lodgments and payments) to banking hall, but extends the banking services and financial transactions to everywhere that internet facility could be found with the aim of reducing the handling of cash for transactions purpose and improving the accessibility to the bank services without reaching the banks, however, its applicability is limited to the banked population. This implies that cashless economy relies on the use of ICT and electronic gadgets for its effectiveness. Ejiofor and Rasaki (2012) [9] opined that cashless system is the ability to store money in an electronic purse on a card and is fast becoming standard practice throughout the work place. The electronic purse is then used to purchase products at the vending machine or at any point of sale terminal. Ajayi (2014) [10] reemphasized that cashless economy does not mean a total elimination of cash as money would continue to be a means of exchange for goods and services. It is a financial environment that minimizes the use of physical cash by providing alternative channels for making payments. Olaonipekun et al. (2013) [11] asserted that electronic transaction is a sine qua non to the implementation of cashless policy as it is desired to make it succeed. Electronics cash is a system that allows individuals to purchase goods or services in today’s society without the exchange of anything tangible. Osazevbaru and Yomere (2015) [12] defined cashless policy as the system which aims at reducing, but not eliminating the volume of the physical cash circulating in the economy while encouraging more electronic based transactions. In other words, it is a combination of e-banking and cash-based system. The study states further that it is a mobile payment system which allows users, but makes payment through GSM phones with or without internet facilities. In a cashless economy, “how much cash in your wallet is practically irrelevant. You can pay for your purchases with any of the plethora of Automated Teller machine (ATM), Points of sale terminals, Electronics Purse, Wallets, credit/Debit cards, Smart cards, telephone banking, PC banking; cheque, bank transfers, payments cards, mobile payments (Akhalumeh and Ohiokha, 2012; Adebisi, 2012) [12, 13].The second objective stipulated by the Nigeria Cashless economic policy is financial inclusion along with reduction in cost of banking. Financial inclusion of the chunk of the micro entrepreneurs segment of SMEs in the informal sector of Nigeria required a serious attention by the policy makers and the researchers. “65% of the cash in circulation in the Nigerian economy are outside the banking system, thus, severely limiting the impact of CBN’s efforts (monetary policy efficacy) in price and economic stability” (CBN, 2011 as cited in Alagh, (2014)) [14]. Logically, a larger proportion of the cash outside the banking system is accounted for by the 36.9 million Nigerian adult populations that are unbanked.Financial Inclusion according to CBN (2012) [15] implies easy access to a broad range of formal financial services that meet their needs and are provided at affordable cost. It is not only accessible, but the usage of a full spectrum of financial services including but not limited to payments, savings, credit, insurance and pension products. Achieving financial inclusion in the payment sector is a two-step process: excluded people must have an account at a regulated financial institution that allows them to store electronic value; people must be able to use their account at a regulated financial institution to initiate or receive electronic transactions beyond simply withdrawing cash at an ATM (EFInA, 2013) [16] Financial inclusion necessitates availability of multiple channels to initiate and receive electronic payments by the sundry. Uchenna et al. (2014) [17] documented that financial inclusion connotes an increasing access to formal financial services such as having a bank account, and using credit and saving facilities of banks. The study did further justice to the concepts by affirming that financial exclusion occurs when access to financial services is hampered despite the higher benefit of it than its cost. The study declared that financial exclusion is unattractive in an economy as its adverse macro-economic effects include low aggregate savings, low domestic investment and inefficacy of monetary policy hence epileptic development of financial system. Nigeria is a signatory to Maya declaration which represents the statement of commitment to develop financial inclusion by developing nations in 2011 during the Alliance for Financial Inclusion Global Policy Forum that took place in Mexico. The nation aimed at reducing the estimated financial excluded adult population of 39.2 million, representing 46% of the adult population (34% of this population are without formal education and 80.4% of them dwell in rural areas) to 20% by the year 2020 (CBN, 2012) [18]. The visit of Her Royal Highness Princess Maxima of Netherlands to advocates reduction in poverty and achievement of developmental goals through the concept and the strategy of financial inclusion is a specific pointer and underscores the importance of financial inclusion as the only key factor to get the other cashless economic policy objectives achievable. To achieve the objectives the following frameworks are set in motion: Simplified Risk-based Tiered Framework- allowing individuals currently without the required formal identification to come under the banking system; Agent Banking Regulatory Framework-delivering banking services outside the traditional bank branches; National Financial Literacy framework-to sensitize Nigerians on financial services; Consumer Protection Framework-to safeguard the interest of clients; Mobile-Payment System and Cashless Policy; Credit Enhancement Schemes and Programmes– to further empower micro, small and medium enterprises (CBN, 2012) [18].This study classified the focus of the research, micro entrepreneurs as the main component of informal sector and classified Small and Medium Entrepreneurs as formal sector in conformity to the classification by the Report of the Vision 2020 (National Technical Working Group, 2009) [19]. Micro-Entrepreneurs in the informal sector in Nigeria were estimated to be 17,281,753 (Seventeen Million Two hundred and eighty one thousand seven hundred and fifty three) while the number of micro-enterprises in Ogun-state is 471,772 (four hundred and seventy one thousand seven hundred and seventy two) (National MSME Survey, 2010). Micro enterprises are SME Subsector with employment size that is less than 10, with an asset value excluding the cost of land and buildings of almost N5million (Report of the Vision 2020, 2009). This sub sector of the economy is dominated by wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing vehicle repair/servicing, transportation, hotels restaurants, building and construction. Micro-enterprises spread all over the country, the majority of them are informal and family owned businesses (Report on Vision 2020, 2009). Todaro and Smith (2011) [20] acknowledged that the informal sector is characterized by a large number of micro enterprises that are individually and family owned and use simple labour-intensive technology. The usually self-employed workers in this Subsector have less formal education. Theoretically, this study adapts the Dualistic Development Thesis as the underpinning theory. The notion of dual society is fashioned into the monetary/financial development quest brought about by the introduction of the cashless economy monetary policy implicit in the structural change theory. Dualism represents the existence and persistence of substantial and increasing divergences between formal sector and informal sector participants. The four key arguments that the traditional concept of dualism embraces as pointed out by Todaro and Smith (2011) are adapted to the study at hand.Differences in the socioeconomic features of the participants in formal and informal sector co-exist in the country. The coexistence of the educated, who are agents of change, who can turn on positively to the new cashless policy in the formal sector and the masses of neo-literates who are resistant to change, who can turn on negatively to the new cashless policy.The coexistence is chronic and not transitional. It is not a temporary phenomenon. The formal sector operators depend on the informal sector participant on certain economic activities whereby the flow of cash from the formal sector participants to informal sector operators is inevitable. Hence, the flow of cash from formal sector operators to informal sector participants is tantamount to leakage of cash out of the banking system. In other words, the formal sector participants would promote or serve as spur to the achievement of the objectives of cashless policy and the informal sector participants would serve as drag to the accomplishment of the cashless objectives.The participants in informal sectors continue to interact with one another economically without the use of banks for financial transactions.The interactions of these subsectors do little or nothing to pull up the informal sector participants to embrace change. If no drastic, calculated and holistic measures are taken by the apex monetary authority to integrate the micro entrepreneurs to this monetary developmental policy the Subsector could continue to serve as the cog in the wheel towards the accomplishment of the developmental objectives put in place by the policy.Empirically, International Monetary Fund (2015) [21] on selected issues of promoting economic transformation - development imperatives, acknowledged that access to credit (financial inclusion) especially for micro enterprises is low, limiting growth potential. The study revealed that only 2 percent of the adult population had loans from a financial institution in the past years, which is far below the world average of 9 percent. The study further documented that financial inclusion could help alleviate negative shocks to micro enterprises. In view of this, cashless monetary policy is inevitable policy to drive financial inclusion which must carry micro enterprises along in order to have a success story.Solomon (2014) [22] investigated Financial Inclusion, a Tool for Poverty Alleviation and Income Redistribution in Developing Countries: Evidence from Nigeria. With the main aim of determining the current state of financial inclusion and financial inclusion strategies adopted in Nigeria. The research took a quantitative descriptive dimension by analyzing the secondary data. The finding of the study reveals that financial inclusion constitutes an important tool for alleviating poverty and redistribution of income in developing country like Nigeria. Benjamin (2013) [23] explored Mobile Banking and Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Nigeria. With the purpose of identifying ways by which entrepreneurial mobile banking growth in developing countries could be accelerated. Qualitative exploratory research was used as the methodology of the analysis. The study reveals that competition among banks and the need to deliver financial services with greater efficiency to their numerous customers at minimal cost will continue to motivate banks to adopt mobile banking as an alternative channel of delivering financial services. Chibango (2014) [24] investigated Mobile Money Revolution: An Opportunity for Financial Inclusion in Africa. With the objective of determining to what extent the mobile money banking as included the unbanked population in Zimbabwe by adopting a desktop research approach. The study reveals that the people who resides in rural areas are socially excluded because formal financial institutions fail to take banking services to this area due to fear that they may not be able to recover their cost. Igbara et al. (2015) examined the Impact of Cashless policy on Small Scale Businesses in Ogoni Land of Rivers State, Nigeria. The objective of the work was an examination of the impact of cashless policy on small scale businesses in Ogoni land laying specific emphasis on identifying the challenges that have hindered the adoption of the cashless policy by small scale business in the area. The study used a survey method to accomplish its objectives. The results of the study indicated that the significant numbers of the small scale enterprises have a very poor banking habit and have zero tolerance to ICT. Ebeiyamba (2014) [25] looked into the Effect of Cashless Economy on Micro and Small Scale Business in Nigeria. The objective of the study was to determine the possible implication of a cashless economy of a cashless economy on micro businesses in Nigeria. This study adopted descriptive and analytical approach in its methodology of analysis. The study concluded that if the necessary stakeholders like micro businesses too are not carried along, the cashless policy will have adverse effects on micro business operators.There is an avalanche of research works on the cashless policy, but they focus on the prospect, benefit, problems and challenges of the discourse (Akhalumeh (2012) [21], Odior and Banuso (2012); Ejiofor and Rasak (2012); Osazevbaru and Yomere (2015); Mieseigha and Ogbodo (2013); Emegwu and Emeti etc.). The objectives of the scanty studies that focus on the cashless policy and the micro enterprises in the country differ from the objective of the study at hand. None of these studies have evaluated to what extent the micro-entrepreneurs are financially included going by the framework and strategies put in place by the CBN. More so, none of them developed a theoretical framework and model with the view of determining the effect of financial exclusion of this Subsector on the achievement of the objectives of the cashless policy obtaining evidence from Ogun-state.

3. Methodology, Theoretical Framework and Model

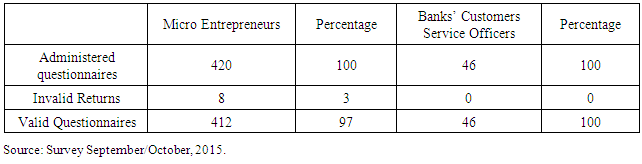

The study adopts survey research design with the help of inferential statistics as a tool of analysis. The research instrument developed was translated into two prominent languages (Yoruba and Pidgin English) in the chosen state of empirical analysis. Meanwhile, the questionnaire items raised by this research work captured the framework, in its bid to determine if micro-entrepreneurs in informal sectors are financially included and to what extent the policy framework adopted by CBN has financially included the Subsector since 2 years of introduction of the policy. The rationale for translation is not unconnected to the fact that most of the targeted respondents are neo-literate hence technical bias and respondent’s errors in the responses are limited. Slight interview was conducted along with the administered questionnaires. Multi-stage quasi random sampling technique is used after the consolidation of 20 local government areas involved into 6 secondary units. The representative sample size of 412 was scientifically determined at 5% significance level, considering the estimated population of micro-entrepreneurs to be 471,772 in Ogun-State. More so, sample size of 46 was chosen among the customer services officers (CSOs) of the banks that have their branches operating in the state. The research work used parametric (One sample T-Test) and non-parametric (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) statistical tool to test the hypotheses formulated. In order to ensure the robustness and reliability of the analysis, Pilot was conducted among 60 micro entrepreneurs in Abeokuta metropolis.Statement of Research Questions1. Does CBN Cashless policy strategy truly take financial services closer to the Micro Entrepreneurs?2. Does CBN Cashless policy strategy justly make payment infrastructures more available and affordable to this Subsector?3. Has CBN cashless policy through its strategy and framework increased awareness of electronic channels to the micro enterprises Subsector of the economy? 4. Does CBN cashless policy strategy, enhance the unbanked and the banked micro-entrepreneurs value proposition?Statement of Research Hypotheses:1. The CBN Cashless policy strategy has not significantly taken Financial Services Closer to the Micro Entrepreneurs.2. The CBN Cashless policy strategy has not significantly made payment infrastructures more available and affordable to this Subsector.3. The CBN cashless policy has not significantly increased awareness of electronic channels to the micro enterprises Subsector of the economy through its strategy and framework.4. The CBN cashless policy strategy has not significantly enhanced the unbanked and the banked micro-entrepreneurs value proposition.

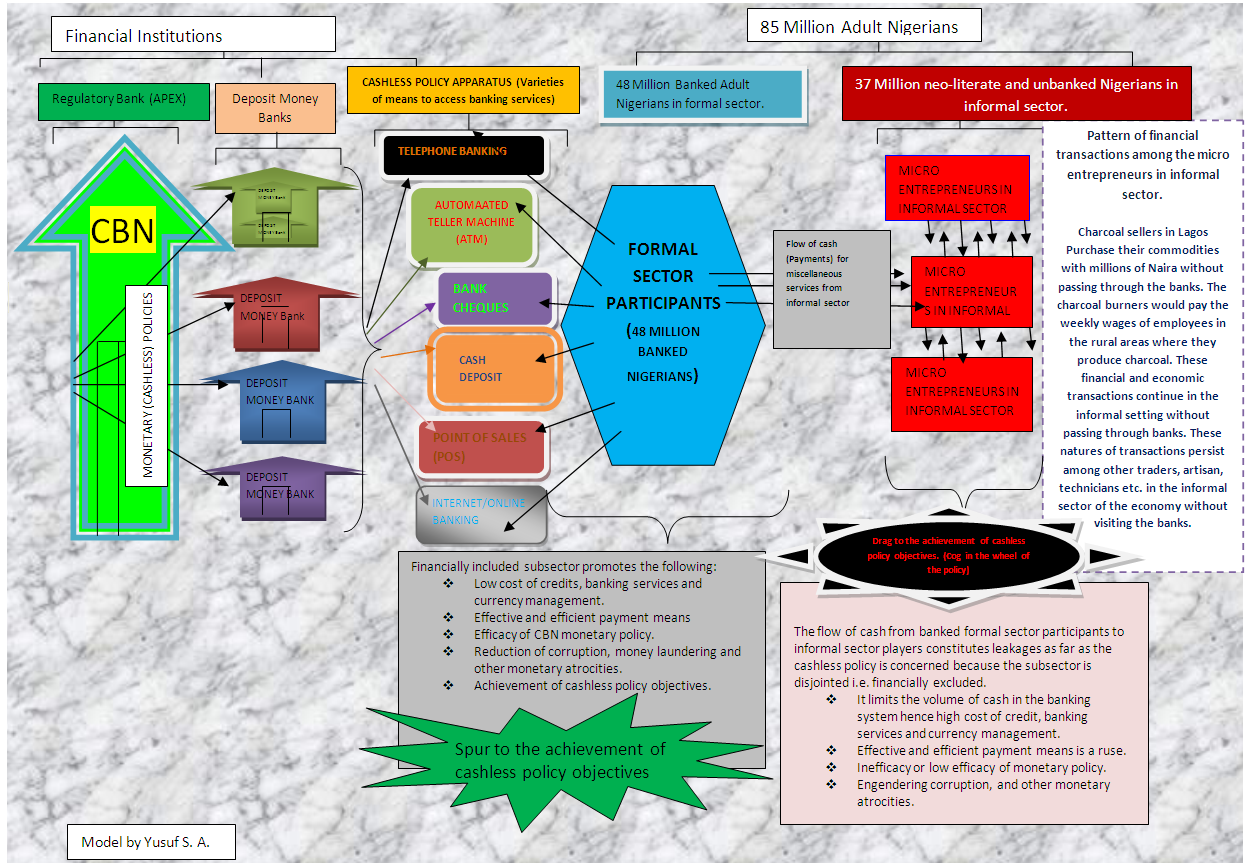

3.1. Yusuf’s Cashless Elasticity of Financial Inclusion Model

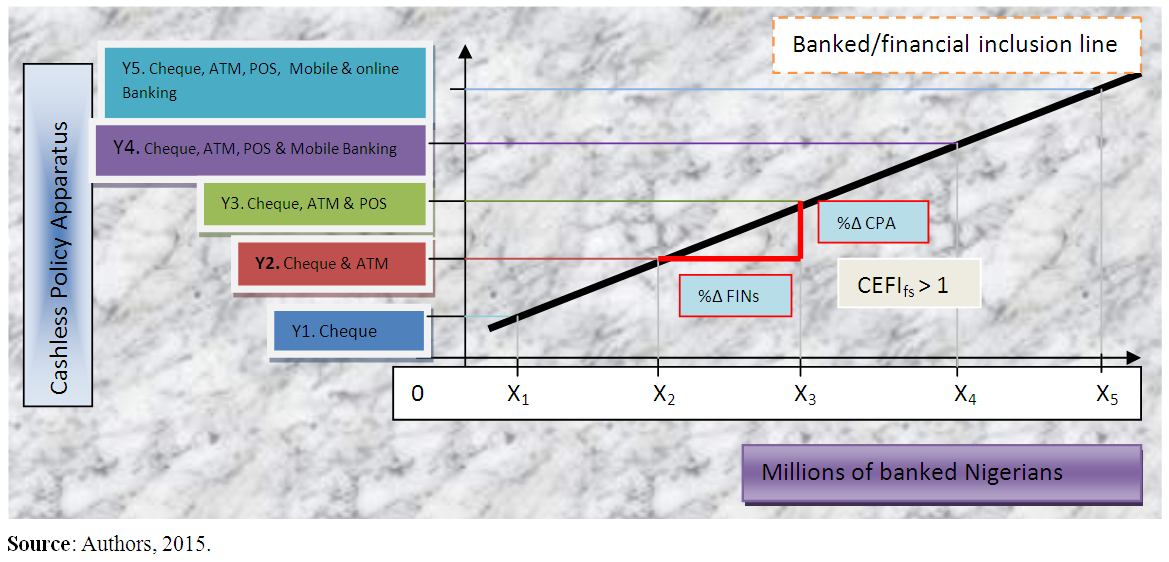

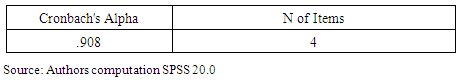

The model postulates that there are variations in the responsiveness of formal sector participants and informal sector participants specifically micro entrepreneurs to the introduction of cashless policy apparatus (banking services). In other words, the introduction of new cashless policy tool promotes financial inclusion more among the participants in the formal sector than the participants in the informal sector. The model emphasized that the degree of elasticity differs from formal sector participants to informal sector players.This model put forward that the cashless apparatus elasticity of financial inclusion is elastic, i.e. almost unity and greater than unity in the case of the formal sector.  | Figure 1. Banked/Financial Inclusion Line (Formal Sector) |

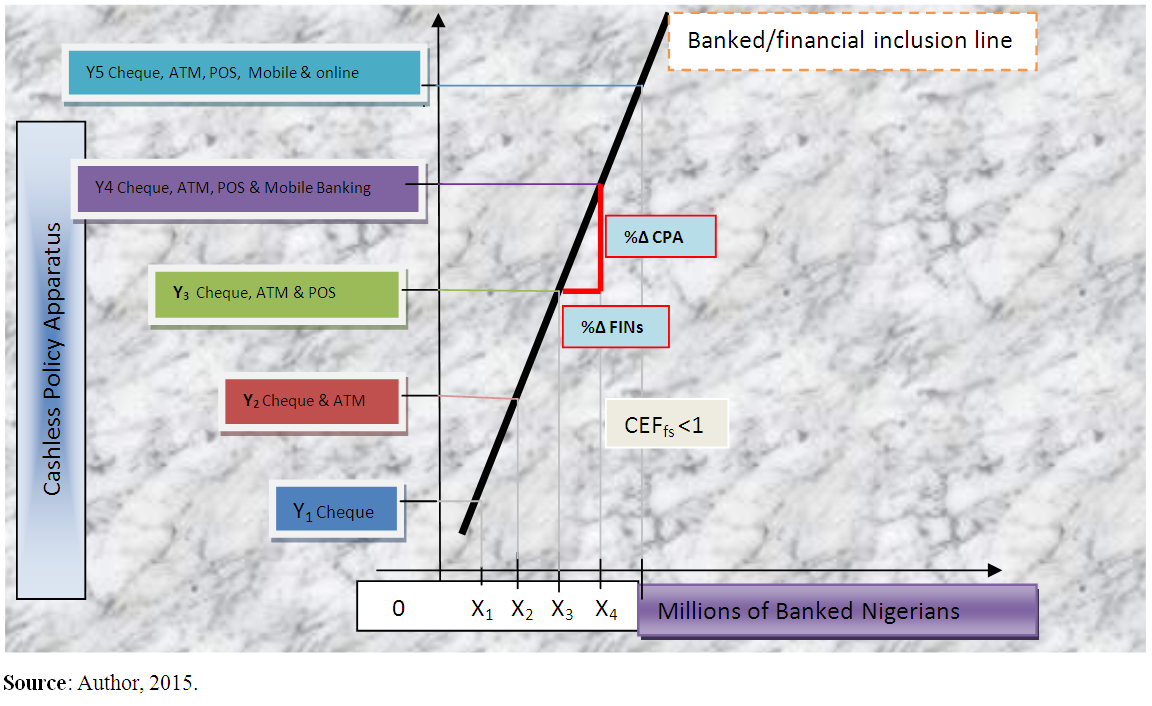

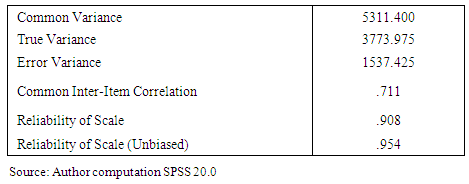

Coefficient of cashless elasticity of financial inclusion is approximately one and greater than one, CEFIfs > 1.In case of micro entrepreneurs in the formal sector, cashless apparatus elasticity of financial inclusion is elastic i.e. approximately one or greater than one. | Figure 2. Banked/Financial Inclusion Line (Micro Entrepreneurs in Informal Sector) |

Coefficient of Cashless Elasticity of Financial Inclusion is approximately zero (0).CEFI = Coefficient of Cashless Elasticity Financial Inclusion,IS = Informal Sector, FS = Formal SectorFIN = Financially Included Nigerians,CPA = Cashless Policy Apparatus, Δ = Change.Assumptions of the Model1. Coexistence of formal sector and informal sector participants. 2. Formal sector dominated by the educated and chunk of small and medium scale entrepreneurs while informal sector is dominated by micro-entrepreneurs that are non-literate or neo-literate.3. Constant cost of banking services to the participants in both sectors.4. There is no restriction to the accessibility of available banking infrastructures to both the formal sector and informal sector participants.5. The micro entrepreneurs are also financially active in their domain. And, would embrace change if they are capable as long as it would enhance their value propositions.

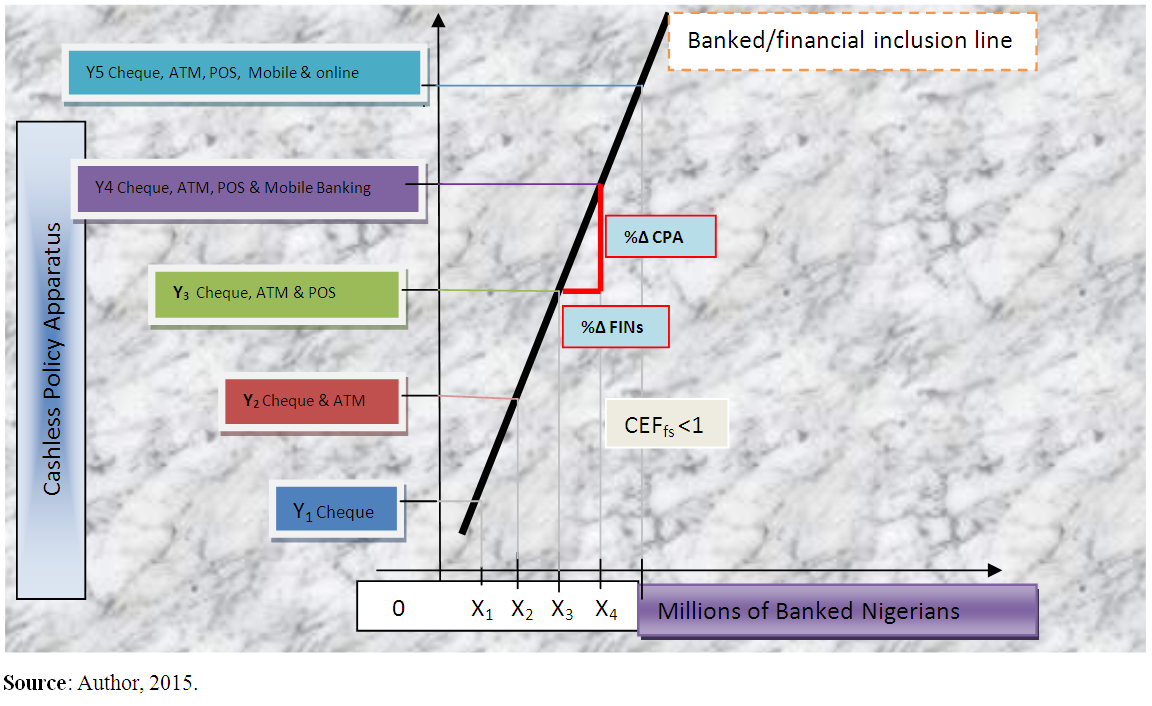

3.2. Theoretical Framework

| Figure 3. Cashless Policy Framework in Formal and Informal Sector |

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Introduction

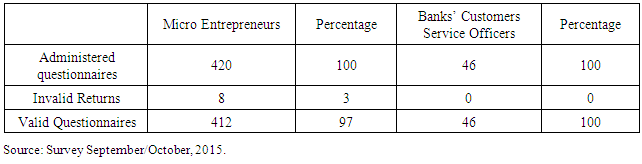

The research work raised many cogent items in the questionnaire that were supported by slight interview where necessary. In order to achieve the objectives of this research work, the questionnaire items that are directly related to the hypotheses and objectives are given attention in this analysis.Table 1. Administration of questionnaire

|

| |

|

4.2. Presentation of Responses

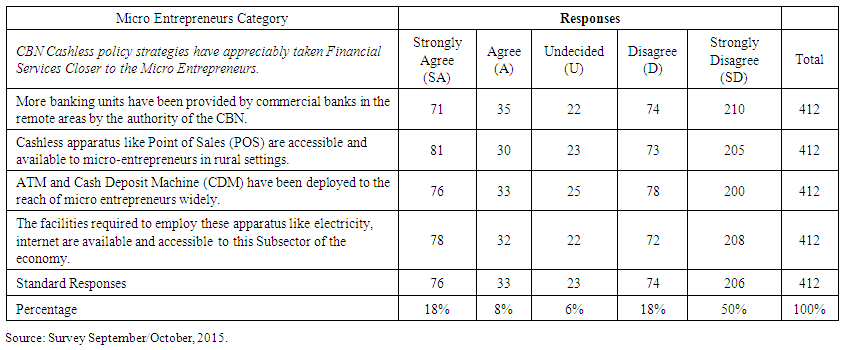

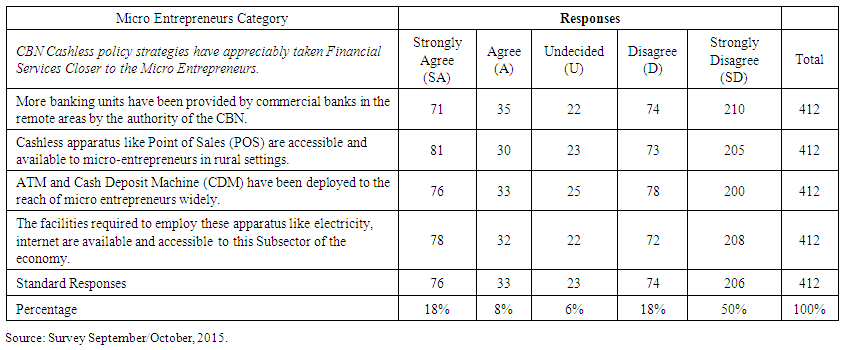

The framework and strategies required to be put in place by the CBN for the achievement of cashless policy objectives were probed and hypothesized for analysis below.Item 1. CBN Cashless policy strategies have appreciably taken Financial Services closer to the Micro Entrepreneurs.68%, representing 280 respondents confirmed that cashless policy through its strategy is yet to take financial services closer to the micro entrepreneurs in their respective rural areas and to the informal sector participants generally, as against the view of 26%. | Table 2. Item 1 Responses |

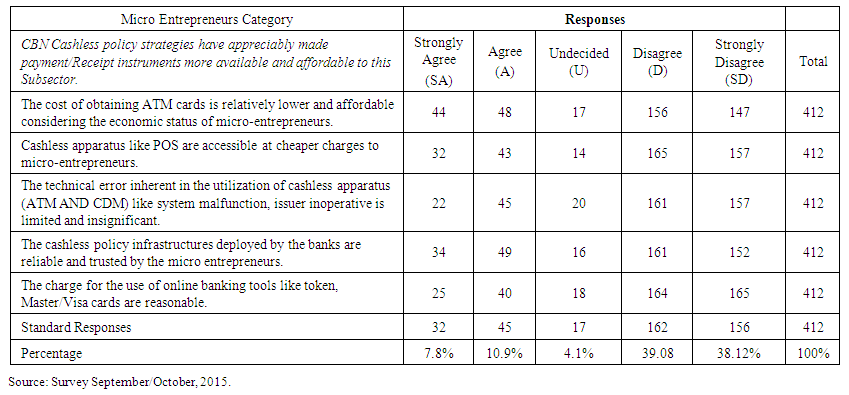

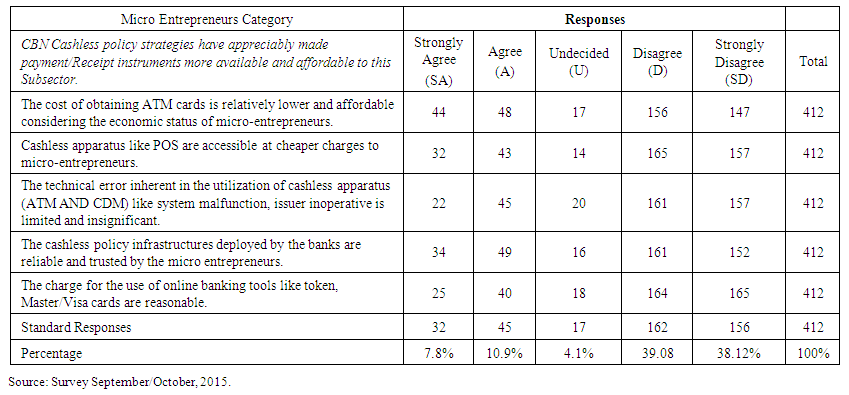

Item 2. CBN Cashless policy strategies have appreciably made payment/Receipt instruments more available and affordable to this subsector.77.2%, representing the opinion of 318 respondents as against the opinion of 78 respondents, agreed that the cost of ATM cards, POS, Token and other bank charges are not affordable to this Subsector considering their socioeconomic status. | Table 3. Item 2 Responses. |

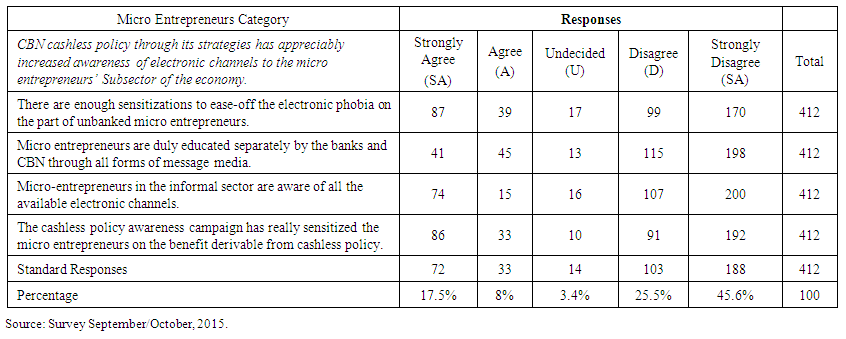

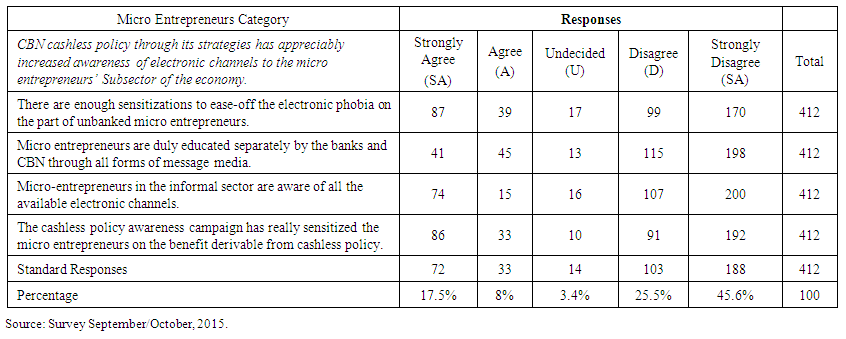

Item 3. CBN cashless policy through its strategies has appreciably increased awareness of electronic channels to the micro entrepreneurs’ subsector of the economy.71.7%, representing 291 opinions of the respondents as against the view of 105 respondents emphasized that the cashless policy through its strategy has not appreciably increased the awareness among the informal sector participants. | Table 4. Item 3 Responses |

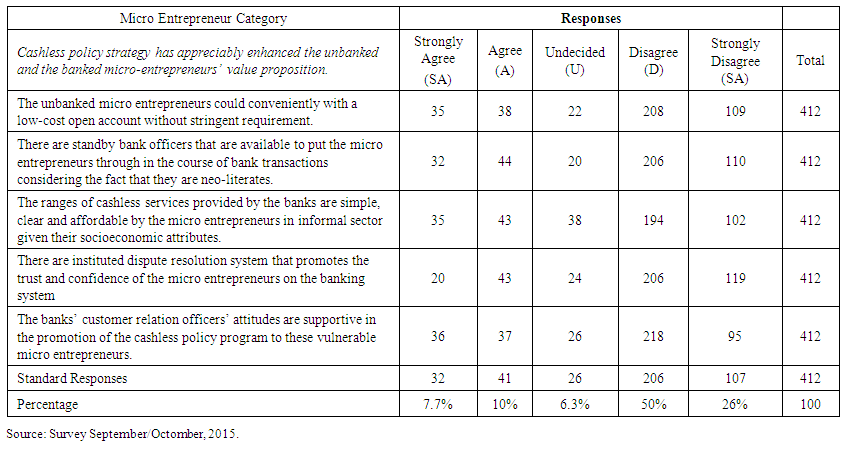

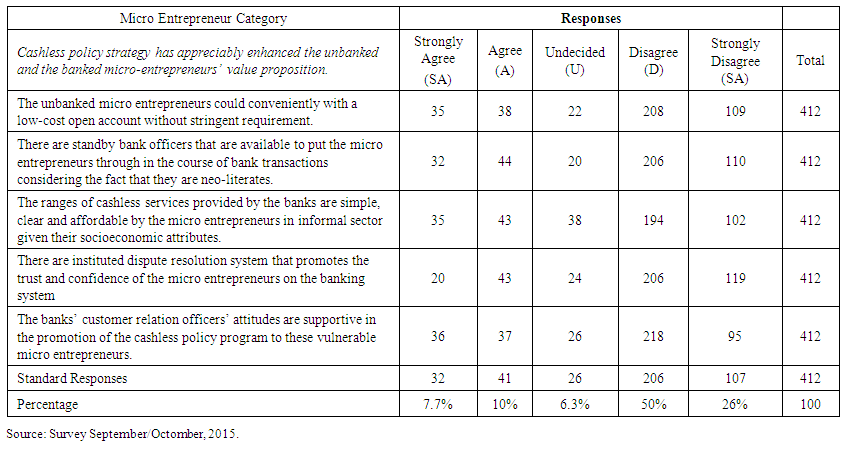

Item 4. Cashless policy strategy has appreciably enhanced the unbanked and the banked micro-entrepreneurs’ value proposition.46.6%, representing 192 respondents as against 137% agree that the micro entrepreneurs (banked and unbanked) value propositions in the informal sector have not been promoted. | Table 5. Item 4 Responses |

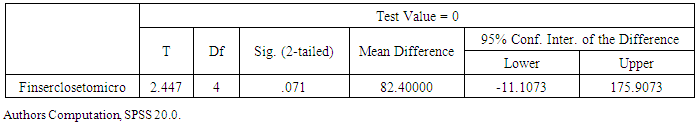

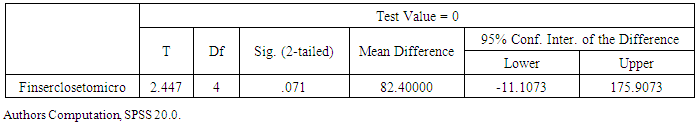

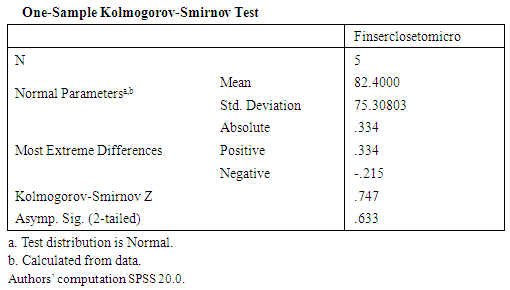

Test of HypothesesHypothesis 1Ho: CBN Cashless policy strategies have not appreciably taken Financial Services Closer to the Micro EntrepreneursTable 6a. One-Sample Test

|

| |

|

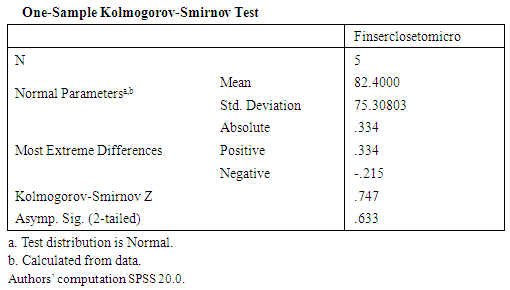

Table 6b. Non-Parametric One-Sample Kolmogorov Test

|

| |

|

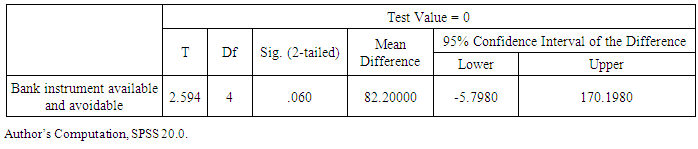

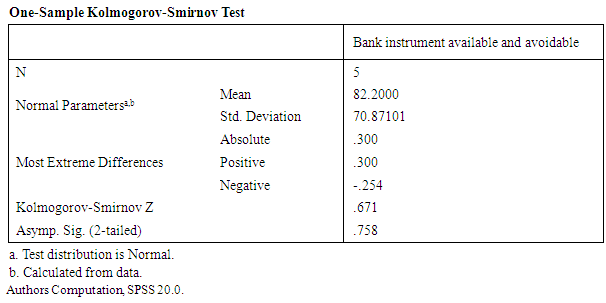

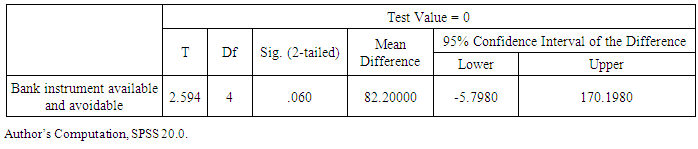

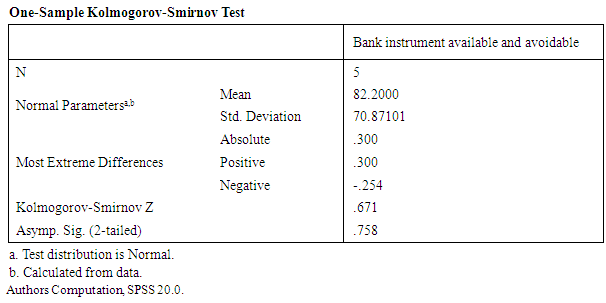

Decision: The null hypothesis which states that CBN Cashless policy strategies have not appreciably taken Financial Services Closer to the Micro Entrepreneurs is accepted because the T calculated value of 2.447 is less than the T table value of 2.776. More so, the asymptotic significant value of KS non-parametric test of 0.633 requires the acceptance of the null hypothesis. Hypothesis 2Ho: CBN Cashless policy strategies have not appreciably made payment/Receipt instruments more available and affordable to this subsector.Table 7a. One-Sample T Test (Parametric Test)

|

| |

|

Table 7b. Non-Parametric One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test

|

| |

|

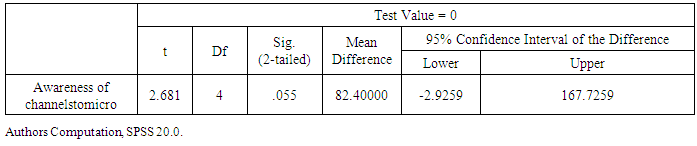

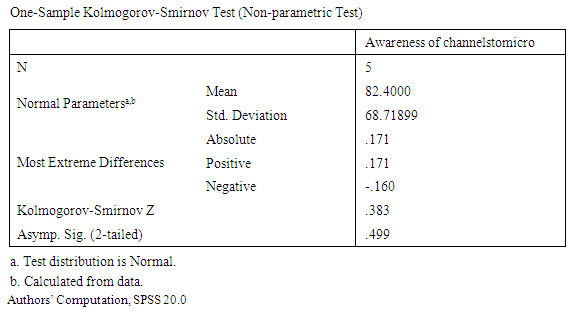

Decision: The null hypothesis which states that CBN Cashless policy strategies have not appreciably made payment/Receipt instruments more available and affordable to this Subsector is accepted on the ground that the T calculated value of 2.594 is less than T table value of 2.776 at 5% significance level and 4 DF. More so, the asymptotic significant value of KS non-parametric test of 0.758 requires the acceptance of the null hypothesis. Hypothesis 3. Ho: CBN cashless policy strategies have not appreciably increased awareness of electronic channels to the micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector of the economy.Table 8a. One-Sample T Test (Parametric Test)

|

| |

|

Table 8b. Non Parametric Test

|

| |

|

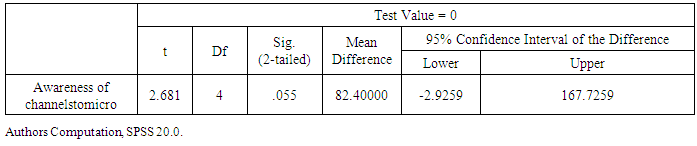

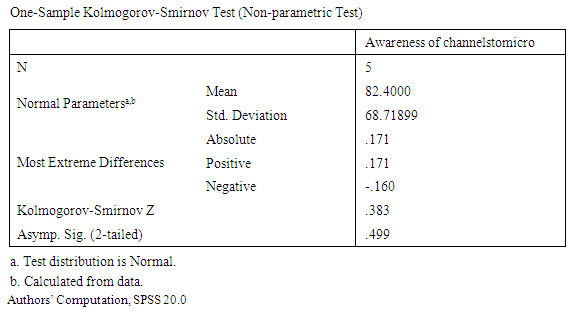

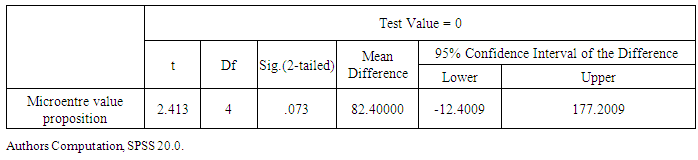

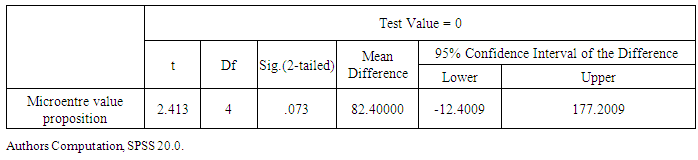

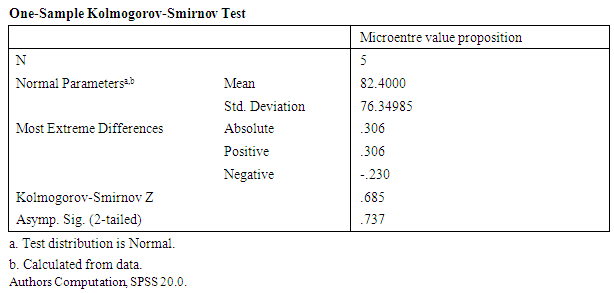

Decision: The null hypothesis which states that CBN Cashless policy strategies have not appreciably made payment/Receipt instruments more available and affordable to this subsector is accepted on the ground that the T calculated value of 2.681 is less than T table value of 2.776 at 5% significance level and 4 DF. More so, the asymptotic significant value of KS non-parametric test of 0.499 requires the acceptance of the null hypothesis. Hypothesis 4.Ho: Cashless policy strategy has not appreciably enhanced the unbanked and the banked micro-entrepreneurs’ value proposition.Table 9a. One-Sample T Test (Parametric Test)

|

| |

|

Table 9b. Non-Parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test

|

| |

|

Decision: The null hypothesis which states that CBN Cashless policy strategy has not appreciably enhanced the unbanked and the banked micro-entrepreneurs’ value proposition is accepted on the ground that the T calculated value of 2.413 is less than T table value of 2.776 at 5% significance level and 4 DF. More so, the asymptotic significant value of KS non-parametric test of 0.685 requires the acceptance of the null hypothesis.

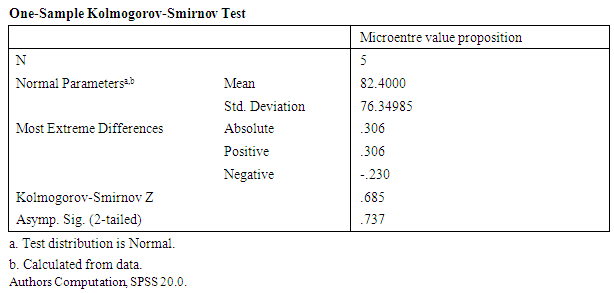

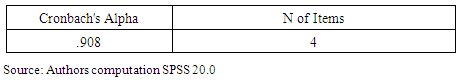

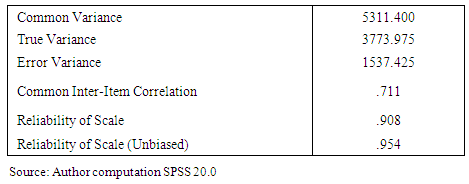

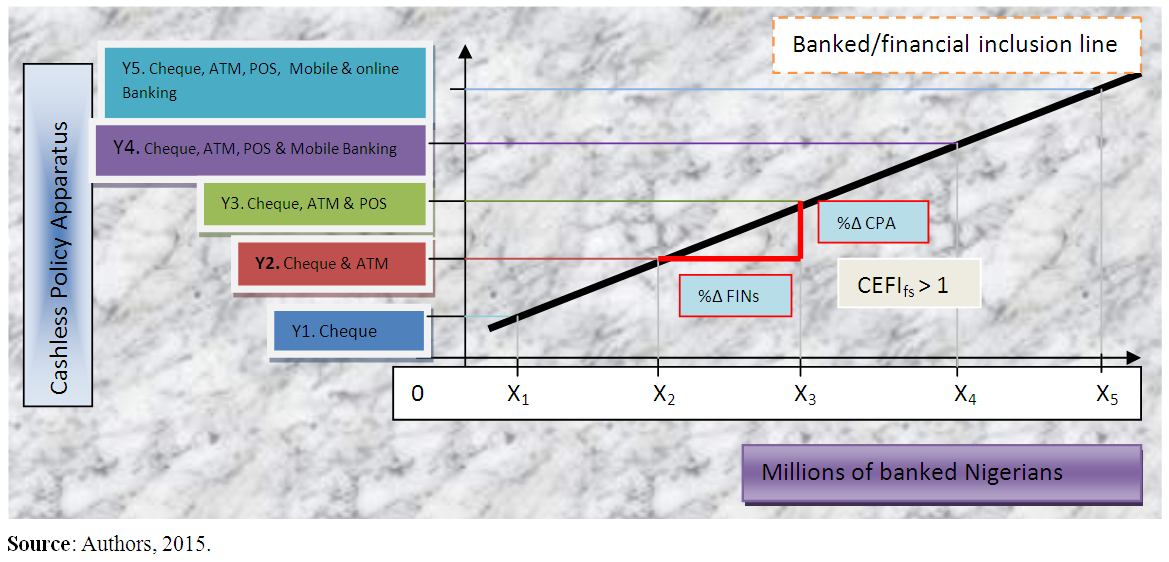

4.3. Reliability Test

Besides the pilot conducted in the month prior to the general administration of the questionnaire for the main study to determine the consistence of the responses, both Cronbach’s Alpha and reliability test under the parallel model assumption are carried out below.Table10a. CronBach’s Alpha Reliability Statistics

|

| |

|

Table 10b. Reliability Statistics

|

| |

|

The above Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient of 90.8% indicates that the analysis of this study is consistent to a reasonable level. The reliability of scale under the parallel model assumption also indicates the same coefficient. Hence, the result of the study is dependable and can be used for policy and decision making.

5. Discussion of the Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Discussion of the Findings

The inference made from the above T statistics and Kolmogorov-Smirnov non parametric test conform to the percentage interpretations of the responses above.The CBN Cashless policy through its strategy is yet to take Financial Services Closer to the Micro Entrepreneurs in the informal sector. This result is not unconnected to the fact that infrastructures (POS, CDM, electricity and internet facilities) required to facilitate the financial inclusion of this marginalized Subsector are not readily available and accessible in their respective areas. More so, the priority of the Deposit money banks that are agents of this policy is the profitability which made them not to open their branch and units in rural/remote and slum areas (unviable places) where the majority of micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector can easily have accessibility to the bank facilities.The CBN Cashless policy strategies have not appreciably made payment/Receipt instruments more available and affordable to this subsector. The charges of N1050 on ATM cards, N1,500 cost of tokens and the charges on the POS are apparently costly considering the economic attributes of the micro entrepreneurs in this subsector of the economy.The CBN cashless policy strategies have not appreciably increased awareness of electronic channels to the micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector of the economy. The available channels are not well appreciated. More so, the sensitization required to ease off the electronic phobia on the part of the participants in this Subsector is inadequate. Many confirmed that they have been hearing ‘cashless policy, cashless policy, cashless policy’ on both the TV and from the radio, but they do not know what it is all about. While some people confessed that they have not heard anything like that before. In fact, many business operators at the rural cities like Ayetoro, Odogbolu, Mowe, Ilaro declared that they have been hearing the policy, but they thought the policy is for the elites and educated “Alakowe” in the city like Abeokuta, Lagos, Ijebu-Ode, Ibadan, Abuja, Port Harcourt etcThe cashless policy strategy has not appreciably enhanced the unbanked and the banked micro-entrepreneurs’ value proposition. The processes required in the opening of bank account are stringent to the extent of wasting the productive time of this Subsector of the economy. The process involves in the installation of the mobile banking application on phones, obtaining the token and procuring other banking utilities are tedious and believed that it would add nothing to their value economically and socially. The micro entrepreneurs in this Subsector have not realized that there are benefits derivable from the cashless economy policy. They are of the belief that the policy has nothing to do with their assets maximization objective.

5.2. Conclusions and Recommendations

In view of the above, the study concludes that the cashless economy policy is lopsided in its implementation it fails to carry the teeming population of micro entrepreneurs in informal sector along. And, the implication of downgrading this Subsector of the economy is detrimental and counterproductive on the achievement of the four highly hyped cashless economic policy. The reason for this is not farfetched; the flow of cash from the participants in the formal sector to the neglected unbanked micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector is inevitable. This flow constitutes the leakage out of the banking system. Consequently, pursuing of the cashless policy objectives would be a ruse.The research work herein set forth the policy prescriptions that would engender the Coefficient of Cashless Elasticity of Financial Inclusion (CEFI) in the informal sector to be approximately one and greater than one. The solution to these challenges of cashless economy policy as far as informal sector is concerned is in twofold: The primary efforts required integrated approach by the Federal Government of Nigeria i.e. it is a national issue. The secondary efforts required the CBN to intensify the frameworks that are necessary to attract and to tow the unbanked into banking net.Primary Efforts/ Issues of National ConcernFirst, far-reaching effort should be made to reduce illiteracy rate. The adult education programme should be strengthened to reduce illiteracy rates to the possible minimum number in the country. The Education for All should be rigorously pursued and implemented, because, only the educated and those that are functionally literate could promote and facilitate desirable change. Secondly, the existing infrastructural framework should be revamped; many rural areas are still off-grid in Nigeria. Government should extend electricity and communication facilities through the electricity distribution company and communication operators by making appropriate legislation to enforce it and throw its political weight in support of its implementation. The road networks linking the urban areas to the rural areas should be constructed maintained and made motor able. As this would facilitate the deposit money banks to open the banking units, if not branch, in the rural sector where they can assign the bank officials to mobilize scanty but huge savings residing and lying fallow with the entrepreneurs in rural areas.Secondary Efforts/ Issues of Concern to CBN CBN as a matter of policy should emphasize the financial inclusion objective and integrate such in the banking policy matter in the sense that Deposit Money Banks operation and location would not only be driven by profitability which has made the Nigeria banks to settle down at the viable urban areas without having branches and units at the rural areas where over 70% of the population resides.The awareness component of the framework put in place by CBN to achieve the objective should be intensified among the micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector. The deposit money banks that are key agents of this policy should extend their branches and units to enhance rural micro entrepreneurs’ accessibility in rural areas. ATM and Cash Deposit Machines (CDM) points should be widespread in the urban and rural areas without centralizing them to urban central. POS should be deployed without discrimination at relatively lower charges. The role of awareness creation is vital to the success of the policy, hence the micro entrepreneurs in informal sector should be made to understand the benefit derivable from the cashless economy policy. The various ways by which the policy could maximize and enhance the micro entrepreneurs’ value propositions in the informal sector should be brought to their awareness through appropriate media.

6. Future Research

The outcome and conclusion derived from the analysis that the CBN has not financially include micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector in the cashless economy policy programme drawing its empirical verities from Ogun state only out of 36 states is the main drawback of this research work. This drawback necessitates the future research to extend the empirical analysis across the nation in order to determine if or not micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector considering their socioeconomic attribute are financially involved in the cashless economy policy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To the Glory of Almighty God.

References

| [1] | CBN (2011). Cashless Lagos Implementation: New Cash Policy Stakeholder Engagement sessions, October, 2012. http//www.cenbank.org. |

| [2] | L. Akinboade, 35m Nigerian adults are illiterates-MINISTER, 2013. http://www.vanguardngr.com/2013/09/35m-nigerian-adults-are-illiterates-minister/. |

| [3] | Survey Report on Micro, Small and Medium Entreprises (MSMEs) in Nigeria (2010). A collaboration between NBS and SMEDAN. |

| [4] | EFInA (2014). Access to Financial services in Nigeria 2014 Survey. http://www.efina.org.ng/our-work/research/access-to-financial-services-in-nigeria-survey/ efina-access-to-financial-services-in-nigeria-2014-survey/. |

| [5] | T.V. Bakare, Writing and Material Production Technique for Neo- Literates. Lagos: Sibon Books Ltd, 2009. |

| [6] | R. Onajite, and N. Nnene, The Imperative of a Policy Framework for Cashless Nigeria. EPPAN Policy Brief Series No. 01, August 2012. |

| [7] | S. A. Yusuf, Informal Sector and Employment Generation in Nigeria, 2014. Online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/55538/. |

| [8] | Basel Committee, Risk Management for Electronic Banking and Electronic Money Activities. Basel Committee Publications, 1998. |

| [9] | V. E. Ejiofor, and J. O. Rasaki, 2012, Realising the Benfits and challenges of Cashless Economy in Nigeria: IT Perspective, International Journal of advances in Computer science and technology. Vol 1, No 1, November – December 2012. |

| [10] | L. B. Ajayi, 2014, Effect of Cashless Monetary policy on Nigerian Banking Industry: Issue, Prospects and Challenges, International Journal of Business and finance Management research. IJBFMR 2 (2014)29-41. |

| [11] | W. D. Olanipekun, A. N. Brimah, and L. F. Akanni, 2013, Integrating Cashless Economic Policy in Nigeria: Challenges and Prospects. International Journal of Business and Behavioral Sciences Vol. 3, No.5. |

| [12] | Osazevbaru and Yomere, 2015, “Benefits and challenges of Nigeria’s Cash-less Policy”. Kuwait chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and management Review. VOL. 4, No. 9. |

| [13] | S. Adebisi, 2012, “Towards a cashless Nigeria: Tools and Strategies: Business Implications. Nigeria Inter-bank settlement System Plc. |

| [14] | Akhalumeh and Ohiokha, 2012, Nigeria’s Cashless Economy: The Imperatives. IJBMS Vol. 2, Issue 2. |

| [15] | J. I. Alagh, and E. E. Emeka, 2014, Impact of Cashless Banking on Bank’s Profitability (Evidence from Nigeria) |

| [16] | Bankable Frontier Association (EFiNA), 2013, What Does CBN’s Cash-less Policy Mean for Financial Inclusion in Nigeria. Enhancing Financial Innovation and Access. |

| [17] | E. Uchenna, 2014, Access to and Use of Bank Services in Nigeria: Micro-econometric Evidence. Review of Development Finance. RDF-52. www.elsevier.com/locate/rdf |

| [18] | CBN, 2012, Launching of Nigeria’s National Financial Inclusion Strategy; Alliance for Financial Inclusion Atrategy peer Learning Group Meeting. http://www.cenbank.org/out/2012/ccd/launching%20of%20the%20nigeria's%20 national%20financial%20inclusion%20strategy.pdf. |

| [19] | Report on Vision 2020, (July, 2009), National Technical Working Group on SMEs.www.ibenaija.org/uploads/1/0/1/2/.../corp_governance_ntwg_report.pdf. |

| [20] | M. P. Todaro, and S. C. Smith, 2011, Economic Development (11th Ed). Pearson Education Limited. Essex, England, 2011. |

| [21] | International Monetary Fund, 2015, Nigeria Selected Issues Paper. IMF Country Report No. 15/85. http://www.imf.org |

| [22] | O. I. Solomon, 2014, Financial Inclusion, Tool for Poverty Alleviation and Income Redistribution in Developing Countries: Evidence from Nigeria. Academic Research International. Vol. 5(3) May 20. |

| [23] | O. A. Benjamin, 2013, Mobile Banking and Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Nigeria; Master Thesis in the Department of industrial Economics, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden. |

| [24] | C. Chibango, 2014, Mobile Banking and Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Nigeria. The international Journal of Humanities & Social Studies. www.theijhss.com. |

| [25] | O. J. Ebeiyamba, 2014, Effect of Cashless Economy on Micro and Small Scale Business in Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Management. Vol. 6, No. 1, 2014. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML