-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2015; 5(6): 574-586

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20150506.03

Transport Choice of Spare Parts Dealers in Accra, Ghana

James Dickson Fiagborlo1, Christian Kyeremeh2

1Department of Liberal and General Studies, Ho Polytechnic, Ho, Ghana

2School of Business and Management Studies, Sunyani Polytechnic, Sunyani, Ghana

Correspondence to: Christian Kyeremeh, School of Business and Management Studies, Sunyani Polytechnic, Sunyani, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper explores the determinants of the choice of mode of transport of intra-city spare parts dealers, and estimates the specific and overall predictions of the discriminant model. Two hundred spare parts dealers in Accra were sampled for this study. Discriminant model was employed to classify the spare parts dealers into their appropriate mode choice to ascertain factors determining their choice of mode of transport. The key findings from the study showed that individual characteristics and mode choice attributes determined the choice of mode of transport of spare parts dealers. In terms of prediction, the study showed that, more than two-third of the original private car users were predicted. The model also predicted over three-quarters of the original bus users. Moreover, the model over predicted the original trotro users, while almost all the original taxi users were predicted. Overall, the discriminant model was successful in correctly classifying about two-third of all original spare parts dealers in the study area. The study concludes with the recommendation that efforts should be made to encourage business private car owners to patronise public transport in their journey to work in Accra.

Keywords: Transport, Choice, Intra-City, Spare Parts Dealers, Discriminant

Cite this paper: James Dickson Fiagborlo, Christian Kyeremeh, Transport Choice of Spare Parts Dealers in Accra, Ghana, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 5 No. 6, 2015, pp. 574-586. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20150506.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Transport is one of the most important catalysts for sustainable development. In developed countries, the transport sector contributes to the GDP by about 10 percent, and its services are a precondition for economic as well as leisure activities. In most developing countries, for example, the last 40 years have been characterised by a dramatic increase in urban populations and auto-centric lifestyle of the citizenry. Growing demands for passenger transport are visible manifestations of an increase in urban population. There is a high demand for motor vehicles, with ownership and use growing at a rate even faster than the population growth rate in most developing countries. Evidence suggests that motor vehicle ownership growth rates of 15 percent to 20 percent per year are common in developing countries (World Bank, 1996).Over the years, transport experts in many developing economies, including Ghana, sought to adopt various innovative alternative strategies, such as car pooling, cycling and mass transport in an attempt to deal with the growing demand for private cars and their impact on road traffic, human health as well as urban transportation. Experts were of the view that a better demand management strategy could ensure efficient use of existing infrastructures. Prominent among these views is the modal diversion from private car to public transport by ensuring that the efficiency of the alternative substitutes is enhanced. Another option, experts maintained is the differential pricing system, whereby different toll rates for different types of vehicle at different times of the day are used. The objectives of all these are to help mitigate traffic congestion during the peak periods in metropolitan areas and to ensure efficiency and sustainability of the sector.Studies suggest that there is an economic cost of choosing private cars over public transport as discussed extensively by Peirson, Skinner and Vickerman (1996). In their view, private cars are less efficient in bulk carriage of passengers and goods as compared to public transport. Research has also shown that on short distance journeys, the private car engine is cold and runs least efficiently (Potter & Hughes, 1990). Other evidence also indicates that most intra-city journeys are of short duration of about 5 minutes (Ullrich, 1990), and this implies that most private cars operate inefficiently in terms of their energy consumption. It has been discovered that the number of private cars operating in Ghana increased from 20 564 to 22 523 between 2003 and 2005, whiles the number of public buses in operation within the same period increased from 914 to 2 192 (MoT, 2005). Evidence further shows that private car accounts for 34 percent of all average weekday daily traffic generated in Accra. The bus accounts for three percent, with the trotro (which is Ghanaian slag of large vans converted to seat 12-14 passengers and operated by a driver and mate and work along pre-defined routes), taxis and freight vehicles accounting for 25 percent, 20 percent and 18 percent respectively (DoUR, 2005). In the morning peak hour, the story is the same with public bus share decreasing compared to the share of private car. In terms of daily passenger flows in Accra, 56 percent of daily trips are made by trotro, 15 percent of daily trips are made by taxi, with 13 percent by bus and 11 percent of commuters use private car. The rest (5%) of the daily trips are accounted for by other modes (MoT, 2005). Several questions can be asked about why a commuter will prefer one mode to the other. It is difficult to tell whether the reasons relate to the individual making the choice decision or mode choice attributes. Several scholars and researchers have sought to answer the question. In the view of Verplanken, Aarts and Van (1994) making exactly the same journey to work under the same circumstances on the same way every morning, is not guided by deliberate decision, but is habitual. This means that the individuals who frequently travel by car in similar situations may develop a stronger car habit than individuals who sometimes travel by car and another time by public transport. Whichever way one considers the issues, the need to classify intra-city spare parts dealers into their appropriate mode choice groups and to examine factors that determine their choice of mode of transport becomes palpable. This study addresses the following questions: What makes people prefer private car to other modes of transport? What are the factors that will be important in discriminating between the choice of mode of transport of intra-city spare parts dealers? What is the probability of choosing a mode of transport given other modes and personal specific characteristics and mode choice attributes? Literature indicates some factors that influence the choice of mode of transport. Hanson and Hanson (1980) noted that men travel on bus to lesser extent than women. Alpizar, Carlson and Martinsson (2001) discovered that travel time and travel cost are the most important determinants of choice of mode. Mathies, Kuhn and Klockner (2002) found in Germany, Switzerland and Australia that women use public transport more than men and reversibly use cars less frequently. Corpuz, McCabe and Ryszawa (2006) also found that, car users were concerned with speed, comfort and convenience associated with shorter travel time and the flexibility of the trip-making. Mintesnot and Takano (2007) posited that peripheral zone residents, who were public or private company employees and had a larger family size, had a higher probability of choosing bus over taxi. Eno (2007) maintained that women who had unrestricted access to private car persistently preferred the private car mode to public transport. Bill (2008) found no connection between affluence and car usage.It is against this background that the study seeks to use a typical probabilistic model (discriminant function analysis) to classify and predict the choice of mode of transport of intra-city spare parts dealers and to examine the relevant personal specific characteristics and mode choice attributes that determine the choice of mode of transport. We chose Accra because it is the capital city and the main administrative and business centre of Ghana. The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 presents the overview of the public road transport sector in Ghana. Section 3 deals with the methodology. This section outlines the survey method and describes the model and estimation techniques. Section 4 presents the results and discussion. Section 5 provides the conclusions and policy implications.

2. Overview of the Public Road Transport Sector in Ghana

- Road transport is by far the leading carrier of freight and passengers in Ghana’s land transport system. It carries over 95 percent of all passenger and freight traffic and gets to most communities in Ghana. Ghana’s road network was about 38,000 kilometers in 2000. This has increased rapidly to 60,000 kilometers by the end of 2005. The road sub sector has seen gradual improvements. For example, the road condition in 2004 was 36 percent good, 36 percent fair, and 28 percent poor as compared to the desired condition of 70 percent good, 20 percent fair, and not more than 10 percent poor (MoT, 2009). Road maintenance is critical to achieving desired accessibility, affordability, reliability and safety. However, since 1961 it increasingly became difficult to provide adequate funding from the consolidated fund to maintain the road network. A first generated road fund was established in 1985 to solve this problem. In 1997 the Road Fund Act (Act 536) was promulgated to offer a legal framework for road maintenance. This has resulted in great improvements in funding of road maintenance. The current level of the road fund is about 68% of the projected level of maintenance costs (MoT, 2005).Public road transport services in Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA), as is the case for the entire country, are provided by the private sector, which operates a mix of fleets such as buses, trotro and taxis. In 1927, the Accra Town Council operated bus services in Accra, Kumasi, Sekondi-Takoradi and Obuasi. Prominent among the transport operators in this sector in the 1980s was King of Kings Ltd. Its bus operation, which was heavily patronised, was concentrated mainly on the Odorkor-Accra corridor. The company’s operations could not survive the difficult and ruthless environmental conditions of the industry thus it wound up in the late 1980s. Governments over the years have also established bus service companies such as the Omnibus Services Authority (OSA), State Transport Company (STC), City Express Services (CES) amid others. Similarly, operators like STC, CES and OSA in the formal sector have not fared well either, and this compelled the government to divest STC and CES and to liquidate OSA in the 1990s. The Government has quite recently established Metro Mass Transit (MMT) limited for various reasons including government social obligations, environmental factors, energy considerations and the promotion of efficient public transportation to increase productivity and economic growth. It is also in fulfillment of the government’s promise to bus at least about 80 percent of passengers in Ghana, through mass transport (MoT, 2009). Other projects including Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems, School Busing Schemes and Rail Based Mass Transport Systems have also been given due consideration. A number of buses have been imported and are operating in Accra and elsewhere under the management of Metro Mass Transit (MMT) Limited. The Company’s bus Fleet as of December 2007 was 779. As of December 2007, MMT was operating in all 10 regions in the country. At the end of the year 2007, the number of buses that were in good condition for operation was 400 (51%) countrywide out of the total of 779 buses with 379 (49%) bus fleet at workshop (MoT, 2009).The control over the operation of public transport by government is limited to an extent. The private operations are strictly controlled by trade unions of which the most powerful is the Ghana Private Road Transport Union (GPRTU). These unions charge membership fees and member drivers are obliged to register with and pay a daily fee to a local branch, which controls a terminal. The unons also collect user charges on behalf of the Metropolitan or District Assemblies, who own the terminals. As part of their rules, unions require a vehicle to be full before it can depart. This practice is inimical to the interest of passengers, who often cannot board vehicles between terminals and must wait for long periods until the vehicles are full.Generally, quality of services provided by public road transport is poor. This is because most vehicles are old and maintenance standards are to the extreme very low. Sky-rocket vehicle maintenance costs arising from poor road surfaces and limitations imposed on earnings by the acute congestion on the urban roads constrain the operators to invest in new vehicles. The consequence is limited number of low-capacity vehicles and the resultant long queues during the morning and evening rush hours at most terminals in the country (MoT, 2005).The public transport and freight terminals, known in the local parlance as lorry parks, serve all forms of vehicles from private commercial cars and taxis to multiple axle trucks. A few of these parks are paved and there is no clear demarcation between access roads, parking space, and passenger waiting areas. Overall, lorry parks have sprung up near markets and at major intersections. Lorry parks’ development has been ad-hoc, with little account taken of the impact of the vehicle and pedestrian traffic they attract. Lack of their planning has also resulted in vehicles following long and meandering city routes and passengers having to change vehicles most time before reaching their destinations. Problems of public road transport in Accra are eminent. The Department of Urban Roads (DoUR) in 2005 conducted a survey with public transport operators, who classified their concerns as terminal, route, operational or financial problems. According to DoUR, lack of toilets and poor sanitation is clearly the most common problem faced by transport operators at terminals in AMA. From the perspective of the operators, lack of shelters, congestion at access points and congestion within the terminal are also significant problems. Amongst the route problems, congestion (56%), with associated long travel time and high operating cost was the most common problem, the survey indicated. Along routes, insufficient provision of lay byes and bus stops was one of the most frequently identified problems cited by the operators. One third of the survey respondents mentioned conflict with hawkers and pedestrians, inadequate traffic control at junctions and police harassment among others as problems.Furthermore, 28 percent of the operators interviewed claimed poor road signs and absent or faded road markings were problems for them. Driver indiscipline and old vehicles were the only two significant operational problems noted by the survey respondents. These two issues were listed by 50 percent and 44 percent of the survey sample respectively. Financially, high cost of maintenance was the major problem identified in the survey. This was closely followed by high taxes. Low fares and high vehicle replacement costs were the remaining financial problems identified by over 25 percent of respondents.Accra, which is the capital city and main administrative and business centre of Ghana, had a population of approximately 1,659,000 in 2000. It was estimated that by 2013 the combined effect of growth and migration would increase the population of AMA to slightly less than 2 million. It was also expected that the population growth and increasing rates of car ownership would increase the number of cars in AMA from 181,000 in 2004 to over 1 million in 2023, and this is likely to aggravate the already chronic traffic congestion in the cities. Currently, the highest traffic volumes are found in the Winneba Road and Liberation Road corridors, which have volumes over 50,000 vehicles per day at certain points (DoUR, 2005).About 10,000 vehicles also enter the central area of Accra within the Ring Road in the morning peak hour and on a typical weekday, 270,000 vehicle trips are made into, or out of, the Accra central area. In the morning peak hour, higher volumes of about 16,000 inbound vehicle trips and 300,000 daily vehicles trips in both directions cross into the area inside the motorway extension. These vehicle trips consist of 50,000 inbound passenger trips into the Accra central area and 85,000 trips into the area inside the motorway extension in the morning peak hour. Approximately 1.3 million passenger trips per day are estimated to enter or leave the area within the Accra Ring Road and 1.6 million passenger trips into or out of the area within the motorway extension (DoUR, 2005).Eighty four percent of these passenger trips, according to Urban Road, are made by public transport. Over half (56%) of daily passengers are carried by trotros, and a further 15 percent by taxi. About 1 million passenger trips are made each day into and out of the central area of Accra using trotros and taxis. In Accra the average number of passengers carries by trotros and taxis per trip are 13 and 2.3 respectively. The implication of this is that these vehicles are inefficient in terms of congestion caused and the amount of road space used to transport each passenger. In a situation where the intra-urban journey is short, most of these vehicles also experience inefficiency in terms of high energy consumption per time as well as per passenger.Congestion is a major problem on arterial routes in Accra, and this leads to 70 percent of major roads operating at unacceptable level of service at some time during the day (less than 20 km/h). Although considerable scope exists to improve the efficiency of people movement through a shift from low capacity public transport vehicles to large and double-decker or articulated buses with the potential to carry over 100 passengers, the concern is whether this will really work given the nature of roads and the volume of daily traffic congestion on all the corridors in the cities. Any attempt to shift from one mode to the other is also likely to face some challenges due to pervasive popularity of private cars in Accra and the country as a whole.In summary, the discussion covers public road transport in Ghana and highlights some of the operational challenges pertaining to the public road transport sector in the Accra Metropolitan Area, and finally considers the effects of population growth and increasing demand for motor vehicles on urban transport in the study area. This paper aims at studying the transport choice of spare parts dealers in Accra and the literature is relevant since it reveals much information about the degree of transports that is used by travellers in Ghana.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area and Data

- Abossey Okai is the study area for this research. It is situated in the Accra Metropolitan Area (AMA) of Ghana. The AMA is one of the largest assemblies in the country. The AMA is bordered in the North, West and East by other Municipal and District Assemblies, and South by the Gulf of Guinea. Accra is the capital as well as the largest urban centre in Ghana. It is located on the coast of the Greater Accra Region, and epitomises the level of socio-economic development in Ghana. Accra has a population of 1 848 614 according to 2 010 population and housing census. For the purposes of this study, the study area was divided into two zones. These are inner zone and peripheral zone. The inner zone residents are spare parts dealers who live in and around the Central Business District (CBD) of Accra. The peripheral zone residents are those who live in the urban edges of the study area. These zones are largely inhabited by all manner of persons but the dominant languages spoken are Akan, Ga and English. Each zone is made up of settlements. The inhabitants, most of whom are spare parts dealers, engage in various activities such as banking, commerce and other administrative duties. Nonetheless, of all the activities engage in at Abossey Okai, spare parts dealing is the dominant one.The data for this research was based on ex post facto survey design. Primary data were collected through survey of individual spare parts dealers in Accra. The study employed questionnaire instruments for data collection and in all, two hundred questionnaires were administered. The respondents were visited at their offices or shops during working hours. If the person at the office or shop could not make a choice decision, the person at the next office or shop next door was surveyed. All interviews were personal where the questions were read aloud to the respondents in English and vernacular (Akan & Ga).

3.2. Empirical Model of Mode of Transport

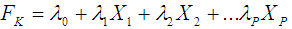

- For empirical estimation purposes, the linear discriminant function for multiple groups was adopted to estimate the likelihood of an individual spare parts dealer choosing a particular transport modality with the grouping or dependent variable being the mode of transport, which was grouped into private car, public bus, public trotro and public taxi. This is of great importance because it will help policy makers to know which personal specific characteristics and mode choice attributes influence transport mode choice decision by spare part dealers in Accra. The standard linear discriminant model is specified as follows:

| (3.2.1) |

3.3. Techniques of Data Analysis

- The preliminary analysis and exploration of the data was done, employing Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS) version 17.0. This was done seeking patterns within responses, looking for casual pathways and connections and constant comparisons (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2000). By the nature of the measurement scales, two other statistical techniques, namely: Descriptive statistics of frequencies to determine whether distribution occurred evenly across categories or whether responses were skewed towards one end of the rating scales were employed. This enabled a meaningful description of the data with numerical indices

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML