-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2015; 5(5): 501-507

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20150505.10

Public Debt and Private Investment in Nigeria

Kehinde John Akomolafe, Olanike Bosede, Oni Emmanuel, Achukwu Mark

Department of Economics, Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Kehinde John Akomolafe, Department of Economics, Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The study investigates the effect of public borrowing on private investment in Nigeria. The study divides public debt into external debt and domestic debt. Johnasen Co-integration test and Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) were used in the analysis. The results show that domestic debt crowds out domestic investment in both short run and long run. However, the result indicates that external debt crowds in domestic investment in the long run. The result concludes with some recommendations that government should strive to reduce her debt profile by improving its revenue base through diversification of the economy, and that any new borrowing is judiciously utilized for the purpose for which it was taken.

Keywords: Public Borrowing, Private Investment, Gross Capital Formation, Crowding-Out Effect

Cite this paper: Kehinde John Akomolafe, Olanike Bosede, Oni Emmanuel, Achukwu Mark, Public Debt and Private Investment in Nigeria, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2015, pp. 501-507. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20150505.10.

Article Outline

1. Motivation

- The importance of economic growth in the life of a country cannot be overemphasized. It is the means of reducing poverty and raising peoples’ incomes. One of the most important determinants of the rate of growth in an economy is the rate on investment. Countries with high rate of investments experience high rate of growth, while countries with low investment rate are slow in their growth process [1]. An economy grows as her investment grows. The desire for a more and secured economic growth has made developing countries seek to enhance their human, institutional and infrastructural capacity. This has often resulted in expansion of government expenditures, inadequate revenue generation, and consequently, increasing debt burden. According to Ajayi [2], developing countries usually take debts because they are in the phase of development, and need extra supports. Hence, public debt is a way of bridging the saving-investment gap, and provides additional investment needed for achieving the needed economic growth. As noted by Mohammad and Sabahat [3], many developing countries have policies to attract foreign capital through loans and other means to enhance growth. Also, Ahmad [4] opined that foreign debt is used to create a sustained growth for the economy that might have been impossible within the pool of domestic resources and level of technology available for the country. This was also echoed by Siddiqui and Malik [5] that foreign borrowing increased resource availability and contributed to economic growth in South Asia. The rationale behind public debt is discussed in what is known as the debt cycle theory. There are three stages in the debt cycle. In the first stage, countries borrow to generate additional resources needed for growth. This enables them to stand on their own feet. By the time they are in the second stage, they continue to borrow because the surplus is probably not enough to offset interest payments. In the third stage, they would have generated sufficient surplus resources with which they can repay the debts. Thus, the aim of public debt is to help the recipient countries develop, sustain and accelerate their economic growth, and pay back the loans from its returns. However, if the purpose of debt is to be achieved, it has to be well managed and the resources channeled to where it will be prudently and efficiently used. However, public debt if not properly managed could lead to more harms than good. For instance, public debt may lead to reduction in private investment. This is referred to as crowding-out in the literatures. As shown by Cunningham and Rosemary [6], the growth of a nation’s debt burden has a negative effect on economic growth. Public debt may crowd out investment through increase in interest rate brought about by public debts. When government finances her budget deficit through domestic borrowing, it reduces the loanable funds available for private investment. This makes the demand for loanable fund higher than its supply. The increased borrowing leads to higher interest rates and reduces the level of private investment. Also, external debt may crowd out private investment. This occurs especially in countries with more dominant public sector. Increased public external debt reduces private sector access to foreign loans because public external debt increases the risk of lending to the private sector. It reduces the available foreign credits, and increases the price of accessing the foreign loan, thereby reducing private access to external markets [7].There have been different views on the impact of public debt on investment in the literatures. While some support the crowding-out effect, others argued that it is actually crowding-in effect. As noted by Friedman [8], debt-financed deficits need not crowd out any private investment, and may even crowd in some. Also, Gehrels [9] noted that public debt issuance increases desired consumption and investment of private sector. Also, Meng and Sumaria [10] opined that external debt could be a source of private wealth if the proceeds from external debt are effectively and efficiently channeled to the people who are willing to consume or lend to the firms who are ready to invest. On the contrary, Sachs [11] pointed out that countries suffering from debt overhang will invest less than it would have done if such an overhang is not there. Consequently, they may forego projects with positive net present value because high debt stock acts as an implicit tax on investment.In Nigeria, the increasing expansion in government expenditures, coupled with the dwindling revenue has often made the government to resort to borrowing. This has made the country one of the largest debtor nations in the Sub-Saharan Africa [12]. The genesis of Nigeria debt began in 1958 when she took $28.0 million from World Bank to finance railway constructions. The debt profile increased to $69.7 million in 1960, and rose to US 246.0 Million in 1970[13]. The debt profile increased to US$9 billion in 1980, and stood at US$19 billion in 1985. The debt stock rose to US $716,815.6 billion in 1995 but came down to US $489269.6 billion in 2004. In 2005, it stands at about US$26,950,072 billion. This was due to interest, surcharges and penalties rather than increased borrowing [14]. The burden of debt payment has been a challenge in the country. As noted by Karagol [15], the cost of servicing public debt can crowd out public investment expenditure, by reducing total investment directly, and private expenditures indirectly. In 2011, the debt service payment was N591.5 billion, out of which N537.4 billion was to service domestic debt, and N54.1 billion for external debt [16]. Out of this, N18.4billion was for interest payment on external debt. Also, total debt as ratio of total revenue increased from %111.8 in 2007 to %144.5 in 2009. This further increased to %183.5 in 2001 [14]. As noted by Iyoha [17], there is a great pressure on the budget of countries with heavy debt burden payment leading to deficit financing. This makes the indebted countries increase tax to service the loans, and thus, decreasing investment. It is in this line that this work aims to estimate the impact of public debt of private investment in Nigeria. This is the focus of this work. This rest of the paper is organized as follows; Section two reviews some literatures. In section three, the methodology is discussed. In section four, the results are presented and discussed. Section five concludes with some recommendations.

2. Review of Empirical Literature

- Using OLS regression, Adofu and Abula [18] investigated the relationship between domestic debt and economic growth in Nigeria from 1986 to 2005. The results show an inverse relationship between domestic debt and economic growth in Nigeria. In the same vein, Onyeiwu [19] studied the effect of domestic debt on economic growth in Nigeria between 1994 and 1998. He employed quarterly data in the analysis, while OLS and error correction model were used as the econometric techniques. They found a negative relationship between economic growth and domestic debt in Nigeria. On the effect of public debt on private investment, Majumder [20] used co-integration and error correction model techniques to examine the crowding-out effect of public debt on private investment in Bangladesh. The result shows that public debt positively affects private investment in the country. This means that there was evidence of crowding in of public borrowing on private investment in the country. On the other hand, Oke and Sulaiman [21] investigated the relationship between external debt and the volume of investment in Nigeria between 1980 and 2008. The result shows an inverse relationship between external debt and investment volume. Also, Apere [22] examined the impact of public debt on private investment in Nigeria from 1981 to 2012. Using instrumental variable technique of estimation and bootstrapping technique, he found out a positive impact of domestic debt on private investment in Nigeria. The result shows further that the relationship between external debts and private investment in Nigeria is U-shaped. This means that the relationship between external debt and private investment is negative up to a threshold level, and becomes positive beyond the threshold level.As important as this issue is, not many studies have been carried out on it using Nigeria data. Most of the studies have focused on the relationship between government expenditure and private investment in the country. The few that have focused on the impact of debt on private investment have either concentrated on impact of domestic debt or external debt on private investment. This paper contributes to previous studies by examining the impact of both the external debt and domestic debts on private investments in the same model, and compares their relative effects.

3. Methodology

- In this chapter, the methodology of the empirical model used to achieve the objectives of this study is discussed. It starts with the discussion on the data type and sources, model specification, and the econometric techniques used.

3.1. Sources of Data

- This work employs Time-series data from 1980-2010. The data will be collected from the Central bank of Nigeria, and the Debt Management Office.

3.2. Model Specifications

- Based on the theoretical framework of the crowding-out hypothesis, this work adopts the model used by Rana and Abid [23] on the relationship between private investment and public debt. The model is modified in line with the aims of this work, and it is presented below:

| (1) |

| (2) |

3.3. Description of the Variables

3.3.1. Gross Domestic Investment

- This is the total change in the value of fixed assets plus change in stocks. It is composed of all domestic investment in Nigeria. It excludes foreign direct investment. In this work, it is proxied by Gross Capital Formation.

3.3.2. Interest Rate

- Interest rate is the users cost of capital. However, it is used as a monetary variable to measure the impact of monetary policy on foreign capital flow. An increase in interest rate would raise the cost of capital and therefore dampen domestic investment. It is expected to be negatively related to GDI.

3.3.3. External Debt

- External debt is that part of the total debt in a country that is owed to creditors outside the country. The sign may be positive or negative. If it is negative, it means there is crowding out, and if positive, it is crowding in effect.

3.3.4. Domestic Debt

- Domestic debt is the debts owed by different tiers of government to the citizens and corporate firms within the country. The sign may be positive or negative. If it is negative, it means there is crowding out, and if positive, it is crowding in effect.Real Gross Domestic ProductThis is the value of value of all goods and services produced domestically. The sign is expected to be positive.

3.4. Econometric Technique

- The econometric technique employed in this work is the Vector Error Correction Model (VECM). According Eagles & Granger [24], applying Ordinary Least Square (OLS) method on time-series data that is non-stationary would yield results that are spurious. The first step in the analysis is to test the time-series properties of the variable. This will be done using the Augmented Dickey Fuller Method. If the variables are found not stationary at level, they will be differenced to ensure stationarity. This will then be followed by the Johansen and Juselius [25] co-integration test. If there is co-integrating equations, we will proceed to the estimation of the VECM.

4. Analysis and Interpretation of Results

- This section presents and interprets the estimated regression results. First, the stationarity properties of the series are tested. This is followed by the co-integration test, the impulse response functions, and finally, forecast error variance decompositions conclude it.

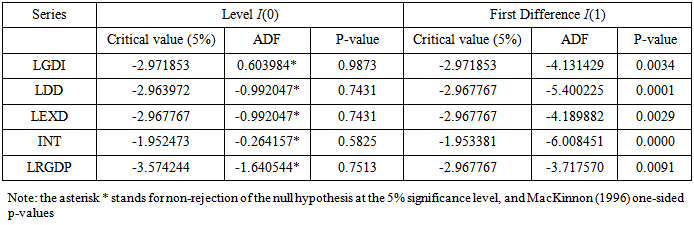

4.1. Testing for Unit Roots Using the Augmented Dick-Fuller (ADF) Test

- It is necessary to verify the stationarity properties of the variables included prior to attempting a multivariate co-integration analysis. This is vital because econometric analysis of non-stationary variables affects the efficiency and consistency of estimation results [26]. To determine the order of integration, ADF unit root test was carried out on levels and differences for variables used in the model. The results are reported in Table 4.1.

|

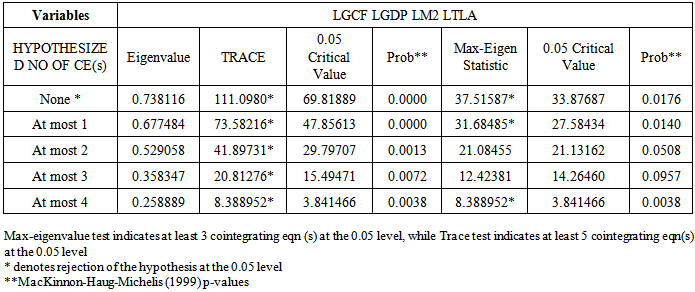

4.2. Johansen Test for Cointegration

- As concluded in the previous section above, the variables are not stationary at level, but stationary at first difference. To test the existence of long run relationship, we use the Johansen co-integration test. Table 4.2 below gives the results of the co-integration test;

|

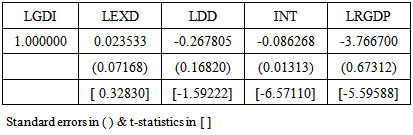

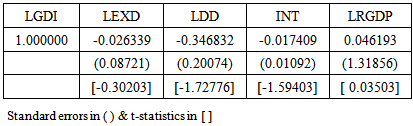

4.3. Vector Error Correction Model

- The VEC model enables us to measure not only the parameters of the co-integrating equations, but also the short-term adjustment parameters. The outcome of the empirical analysis for both the long-run and short run dynamics of the model are presented in the Tables 4.3 and Table 4.4 below respectively;

|

|

4.4. Impulse Responses

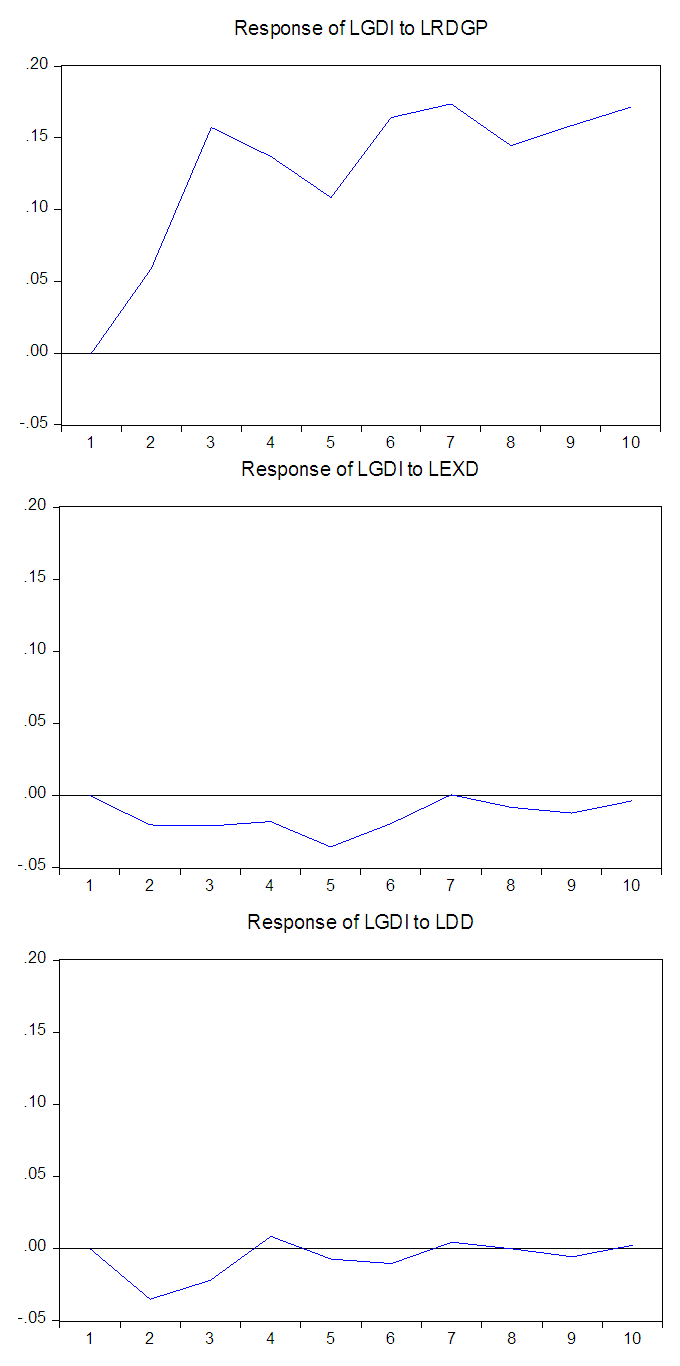

- This section presents the impulse response functions (IRF). The impulse responses are visually presented and analyzed. This is presented in appendix 1.Since this study focuses on the impact of public debts on domestic investment, only the responses of GDI to the variables of concern are presented. The result shows GDI growth responds negatively to external debt growth shock throughout the period. Also, the result shows that GDI growth responds negatively to domestic debt growth shock. However, the result shows GDI growth responds positively a real GDP growth shock.

4.5. Variance Decomposition Analysis

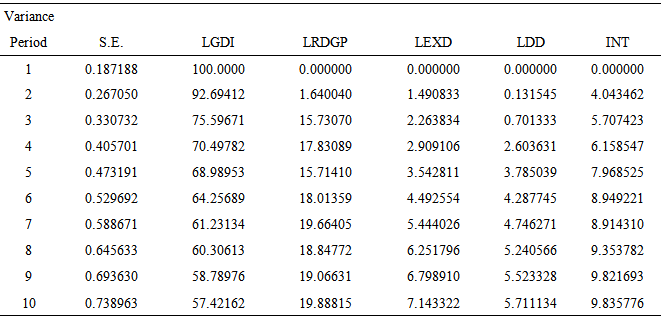

- Variance decomposition analysis provides a means of determining the relative importance of shocks in explaining variations in the variable of interest. In the context of this study, it shows a way of determining the relative importance of shocks to each of the debt variables in explaining variations in domestic investment. The results of the variance decomposition analysis are presented in appendix 2.The result shows that domestic debt respond mostly to its own deviation. Apart from this, the size of the economy, as proxied with real GDP, has the largest influence on the growth of domestic investment with the average of 19% throughout the periods. This is followed by interest rate with average of 9%. Also, the result shows that external debt has a greater influence on domestic investment than domestic debt does.

5. Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Summary and Conclusions

- The study was conducted with a view to examine the presence of crowding-out effect of public borrowing on private investment in Nigeria. To accomplish the task, a model for investment function was specified and estimated considering public borrowing, GDP and interest rate as independent variables. The public borrowing was divided into external debt and domestic debt. The properties of the series was carried out using ADF test, while the long-run and short-run relationships were estimated using the Johnansen Co-integration test and Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) respectively. The results show that all the variables were stationary after first difference. The result also shows that external debt has a positive relationship with gross domestic investment in the long-run, but a negative relationship in the short run. This suggests that external debt does not crowd-out investment in the long run but only in the short run. However, domestic debt has a negative relationship with domestic investment in both short-run and long-run. This shows the existence of crowd-out effect of domestic debt on investment in two periods. As expected, the negative coefficient of the interest rate shows the there is a negative relationship between the growth of domestic investment and interest rate. This means increasing interest rate tends to decrease investment. The result of the size of economy as proxied by the real GDP also shows a positive relationship between the growth of the size of the economy and the growth of domestic investment in the short-run, but a negative relationship in the long run. This is against the expected relationship between the sizes of the economy in the long run. However, the result is line with that of [27].

5.2. Recommendations

- Given the findings of this study, this work concludes with the following recommendations that there is a need to be discretionary in her debt policy. Debts should be taken only when necessary, and should be used for the purpose for which it was taken. Also, since both domestic debt and external debt crowd-out private investment in the short run, government should strive to reduce her debt profile by improving its revenue base.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML