-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2015; 5(3): 394-403

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20150503.11

A Markov Switching Three Regime Model of Tunisian Business Cycle

Imed Medhioub

Department of Finance and Investment, College of Economics and Adimistration Sciences, Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Imed Medhioub, Department of Finance and Investment, College of Economics and Adimistration Sciences, Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

A great interest is accorded to the non-linearities in modelling economic time series. In this context, Medhioub (2007, 2010, 2011) has proved that Markov switching models can capture the business cycle asymmetries of Tunisian economic activity. In this paper, we propose a three regime Markov switching model to analyse the Tunisian business cycle. The results have demonstrated that the Tunisian business cycle is well characterized by three distinct growth rate phases: a recession regime, a moderate growth regime as well as a high growth regime. Based on the filtered probabilities obtained through the Markov switching models, we conclude that the three state model displays a better out-of sample forecasting performance than the two state one. Furthermore, the prior-recognition of the economic transition relating to a new phase of the economic cycle, can be considered as an adequate dating evaluation of the economic cycles in order to present forecasts concerning the real economic activity fluctuations of the industrial production in Tunisia.

Keywords: Asymmetric business cycles, Markov switching model, Three state model, Industrial production, Turning points, Forecasts

Cite this paper: Imed Medhioub, A Markov Switching Three Regime Model of Tunisian Business Cycle, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 5 No. 3, 2015, pp. 394-403. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20150503.11.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- We have recently accorded a great importance to the significant differences existing between the different cycle phases in order to analyse the economic activity. It is obvious that these differences are mainly due to the business cycle asymmetries. The basic idea of this view is that downturns are more violent but less frequent than upturns. However, by using the techniques based on non linear models we try to analyse and identify the economic cycles relating to such economy. In the economic literature, parametric and non parametric tests have been developed to verify if there exist any asymmetries in the data (such as the deepness and steepness tests of Sichel and the triple test of Randles for example). Medhioub (2007) has proved that the monthly data of the Tunisian industrial production for the period 1994–2004 exhibits some cyclical asymmetries. For this reason, we have used the non linear two-state Markov switching model to analyse the economic activity in Tunisia. The use of parametric tests supports the three-state model better than the two-state model. By choosing with this model type, a three-regime Markovchain is then adopted by us. Hence, the economic interpretation of these three regimes is as follows:● A low growth regime: this regime is characterized by a negative growth rate, and is therefore associated to the classic recession phases.● An intermediate growth regime or a regime of moderate expansion: for this phase, we suppose that the economic growth rate is below the trend associated to the growth rate (a growth cycle weak phase) without recession.● A high growth or high expansion regime: for this regime, we suppose that the economic growth rate is above the trend associated to the growth rate (a strong phase of the growth cycles). There is, however, a theoretical reason for which we assume the possibility of using such interpretations concerning the regimes. Yet, in the empirical applications, the relation existing between the different phases of the three regimes and the economic cycles is strong. However, it must be noted that this third regime interpretation considers implicitly a constant long term growth rate. In this paper, we propose to use the three state Markov switching model in our analysis of the Tunisian business cycle. The advantage of these switching processes, frequently indicated in the literature, lies in their capacities to take into account the asymmetry that cannot be caught by linear models. In the Markov switching models, the asymmetries can be explained by introducing the notion of transition probabilities.We have now, at our disposal, an abundant literature which uses the regime switching models for the monthly and quarterly dating of the different economic cycle turning points. In fact, due to the existence of cyclical asymmetries between the different phases, several authors have used Markov switching models. To mention but an example, let’s quote the works of Clements and Krolzig (2003), Kim and Nelson (1999), Anas and Ferrara (2002), etc, according to whom we accept the idea that the economic activity in several countries is well modelled through the three state Markov switching models. It follows from this that the application of the three state switching processes on the cycle of the Tunisian growth rate industrial production offers a better explanation as compared to the two state model. It also presents the best compromise for the cyclical turning points.The rest of this paper is structured as follows: section 2 presents a review of the cyclical asymmetry literature. While section 3 will be devoted to the presentation of the three state switching regime model and to the application of these models on the case of Tunisia, so as to determine the cyclic turning points. Finally, section 4, will be devoted to the forecasting and section 5concludes this work.

2. Asymmetry in the Economic Cycle Literature

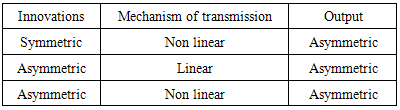

- Detecting and modelizing the asymmetry constitutes a subject of great importance in the study of the economic cycle fluctuations. The asymmetry analysis seems to be fundamental for both the theoretical and empirical studies as pointed out by Mcqueen and Thorley (1993), Sichel (1993), etc. The conceptual study dates back to the forties with the empirical studies of Burn and Michell (1946), in which a first type of asymmetry has been identified. According to these authors, the contraction phase corresponds to a switch more violent than the expansion phase.In a paper, which has initiated the modern literature concerning the economic cycle asymmetries, Neftci (1984) has had the merit to present a statistic evidence of the different types of asymmetries which have been observed in an informal way by Keynes1. DeLong and Summers (1986), Sichel (1993) have noticed an evidence which indicates that the recessions are stronger and more violent than the expansions. Sichel (1993) has noted that the recessions are deeper than the expansions and that the asymmetry is implied by models for which the recessions are transitory and occasional (the expansions are due to permanent chocks). We must, then, note the existence of a relation between the recession durations which is not observed for the expansions. In others words, as soon as a recession starts, it must dispel in a fairly predictable tune period; but the duration of an expansion is not necessary in the prediction of the future recession. Diebold and Rudebush (1990) and Diebold, Rudebush and Sihel (1993) have discussed the notion of dependence concerning the economic cycle durations in a univariate context, whereas Kim and Nelson (1998) have analysed this issue in a multivariate context. All the results have converged towards the fact that the post-war recessions are characterized by positive dependence durations. The more the recession persists, the more it is preferable to end.The literature concerning the shocks persistence has generally imposed the notion of symmetry for the measuring of persistence; for instance, we can mention in this context Nelson and Plosser (1982), Watson (1986), Campbell and Mankiw (1987) and Cochrane (1988). As for Beaudry and Koop (1993), they have taken into account the asymmetry of the impulse response existing in the real crude national product; and they have also noted that the negative innovations of the output are much less persistent than the positive ones. Most of the economists have agreed that the macroeconomic theories justifying the temporary shifts in the output are more important for our understanding of the recessions and the recovery periods, whereas other macroeconomic theorists emphasize the fact that the permanent switching in the output are more important for the expansion of the economic activity. Sichel (1993) and others, have pointed out that the economic cycle asymmetries represent an important feature which can not be treated through linear models, as such models do not generate asymmetric fluctuations. Moreover, the ARIMA models, with Gaussian errors, can never represent an asymmetric behaviour even asymptotically. The following table illustrates the different asymmetric sources that might exist and which depend on the transmission mechanism of random shocks and on the nature of stochastic terms.

|

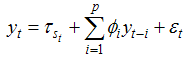

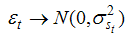

3. Switching Regime Models: The Shift from Two to Three Regimes

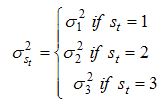

- A great panoply of techniques concerning the non linear time series have been used for the modelisation of the different economic cycle characteristics as the linear models cannot capture the cyclical asymmetries. A great stress has recently been attached to the nonlinear specifications in which we have introduced a significant distinction between the expansion and the recession phases. These models are so flexible that they allow to take into consideration the different specifications and relations corresponding to each phase. Among these non-linear models, there exist the autoregressive threshold models (Tiao and Tsay 1993), the SETAR models (Terasvirta and Anderson, 1992) and the regime switching models (Hamilton 1989). In this paper, we will devote the focus of our study just to the Markov switching models2. In this research, weaimto apply these models to the Tunisian economic context in order to analyse the business cycle asymmetries as well as determine the turning points. According to Hamilton’s supposition, the economic growth is divided into two phases: a negative growth rate phase and a positive one. In addition, he has supposed that the economic activity, which shifts from one process to another, is governed by a "latent state" variable. Moreover, following a trough relating to a recession, the economic activity output shifts to a growth phase (the output knows again a growth phase), and it is, therefore, not possible to regain all the loss occurring during the recession phase. Consequently, the impacts of the recession phases upon the output level are permanent. This view is one of the main findings of the empirical analyses dealing with the economic cycles, and which are raised by several authors such as Kim and Piger (2000), on their use of an alternative non linear model. This model implies that the recession is characterized by periods during which the output is stricken by negative transitory shocks, termed "plucks" by Friedman. According to such an alternative, after the trough, the output will consequently meet a recovery regaining phase, taking the series back to its usual trend. This “bounce-back” effect or “peak reversion” is the critical phase of Friedman model, once more considered by Kim and Nelson (1999). The output is characterized by three growth phases: the first of which is a normal phase, while the second one being slow, and the third is characterized by a high expansion.Similarly, the conclusion of Sichel (1994), considers the fact that recessions are usually followed by rapid growth periods. On the bases of various researches, we propose to use a three process model of economic cycle for the purpose of capturing the recession and the recovery episodes respectively considered by the negative and the positive persistent deviations of the growth rate mean from the long run normal growth rate (Krolzig 2000).Sichel (1994) has argued that the post-war economic cycles in USA contain three phases: a contraction phase followed by a strong recovery growth and which later shifts into a moderate growth period. To better understand these concepts, we consider the three regime Markov switching model, called MS(3)-AR(p), developed by Clements and Krolzig (1998). By supposing a switching regime at the level of the intercept and of the variance3 (errors heteroscedasticity), the model can by written as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

and

and

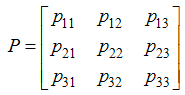

According to these two last expressions, we suppose that the recovery as well as the expansion and the recession periods are modelled as being a switching regime of the stochastic process generating the output growth rate. These different regimes are associated with the different conditional growth distribution where the intercept is positive in the both regimes of expansion (the regime of moderate growth phase and that of recovery period). The intercept is generally negative during the recession phase. Following a switching regime, there exists an immediate jump at the level of the intercept. Examining the variance expression which varies from one regime to another, we are able to consider the Markov Switching Intercept Heteroscedasticity model (called MSIH model).Similarly, regarding the intercept, following a switching regime, there exists an immediate jump in the errors variance. It is supposed that, during the recovery periods, the variance is larger than that of the recession phases, while the expansion is supposed to be the least volatile period.Concerning the specification model, the transition probabilities, which are supposed to be constant over time, are assigned to then on observable state in order to represent the nature of the economic activity: “recession, expansion and recovery”.

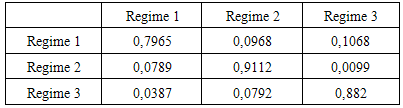

According to these two last expressions, we suppose that the recovery as well as the expansion and the recession periods are modelled as being a switching regime of the stochastic process generating the output growth rate. These different regimes are associated with the different conditional growth distribution where the intercept is positive in the both regimes of expansion (the regime of moderate growth phase and that of recovery period). The intercept is generally negative during the recession phase. Following a switching regime, there exists an immediate jump at the level of the intercept. Examining the variance expression which varies from one regime to another, we are able to consider the Markov Switching Intercept Heteroscedasticity model (called MSIH model).Similarly, regarding the intercept, following a switching regime, there exists an immediate jump in the errors variance. It is supposed that, during the recovery periods, the variance is larger than that of the recession phases, while the expansion is supposed to be the least volatile period.Concerning the specification model, the transition probabilities, which are supposed to be constant over time, are assigned to then on observable state in order to represent the nature of the economic activity: “recession, expansion and recovery”. 3.1. Estimation of the Three-state Model

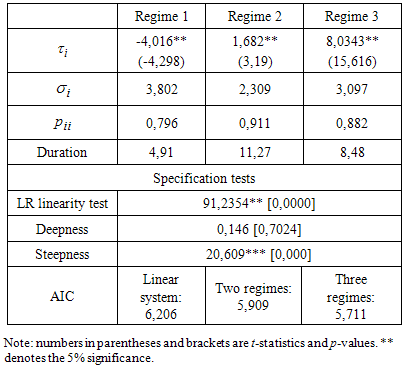

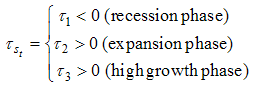

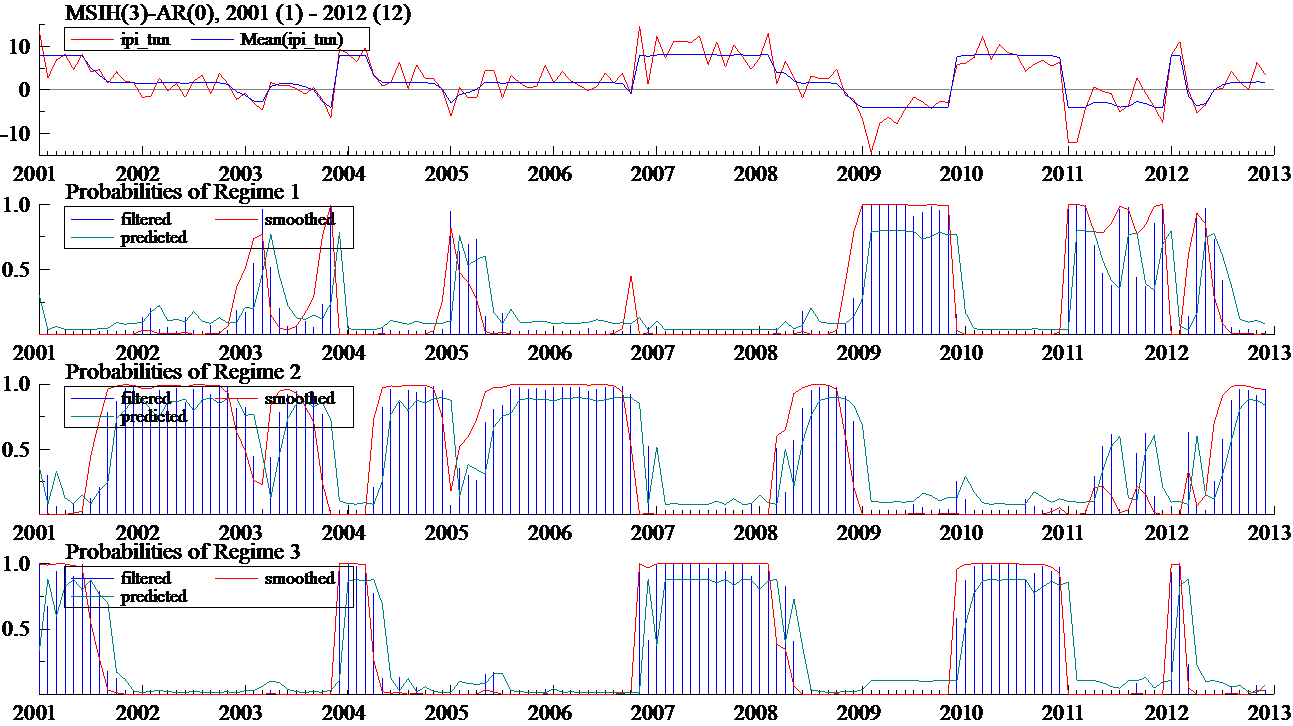

- This subsection is devoted to estimating the three-state Markov switching model, bearing in mind that in Tunisia, there exist three phases characterizing the economic cycles. The data considered in this study correspond to the monthly data of the industrial production seasonally adjusted from the period 2000:01 to 2012:124. In figure 1 we present the first differences of the logarithm of industrial production seasonally adjusted multiplied by 100 which correspond to the growth rates.

| Figure 1. Growth rates of the Tunisian industrial production seasonally adjusted |

|

|

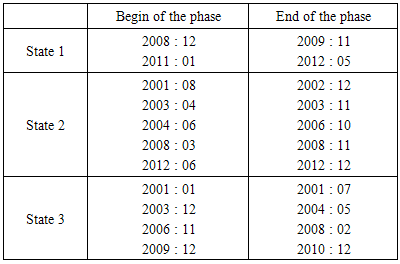

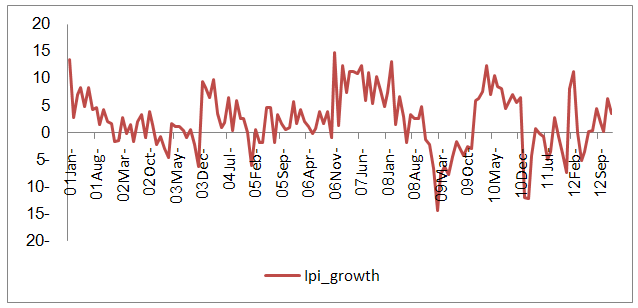

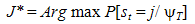

3.2. A Turning Point Chronology for the Tunisian Industrial Production

- A basic question about which policy makers and economic agents are concerned, deals with the detection and the forecast of the switch among the business cycle phases. In the United States, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is a reference organism interested in determining the different phases of the American economic activity. In this section, we are trying to determine the expansion and recession periods in the Tunisian economic activity. In fact, we notice the absence of any committee interested in this kind of work in Tunisia; even the economic agents along with the political decision makers anticipate the periods of crisis by intuition. In this research, we try to use the index series related to industrial production a reference in our bid to determine the cyclical turning points during the same period about which we have estimated our model. The reasons of our choice are twofold: first being the fact that, in most previous works, we have chosen this series as a reference for the economic activity. The second of which being the fact that the validity of this series for a long period at a monthly frequency.Similarly to what has been applied to the two-state model, we are trying to present in this paper the different dating of the economic-cycle turning points by using the three-state switching regime model as has just been estimated above. The main advantage we can mention in favour of these parametric models as compared to the non parametric methods, for instance the turning points dating method of Bry and Boschan, is its ability to determine the turning points for more than two regimes.Concerning the turning points dating, we apply the following rule: once the model parameters are estimated from the data, we obtain the filtered probabilities P[st=j/ψT], j=1,2,3 as well as the smoothed probabilities P[st = j/ψT], j = 1,2,3. These smoothed probabilities are used for the classification of the observations among the three regimes. The classification rule is very simple and consists in assigning each observation in the regime with the highest probability.

| (4) |

| Figure 2. Mean of industrial production growth rates and smoothed, filtered and forecasted probabilities from the MSIH(3)-AR(0) model |

|

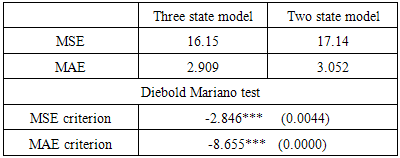

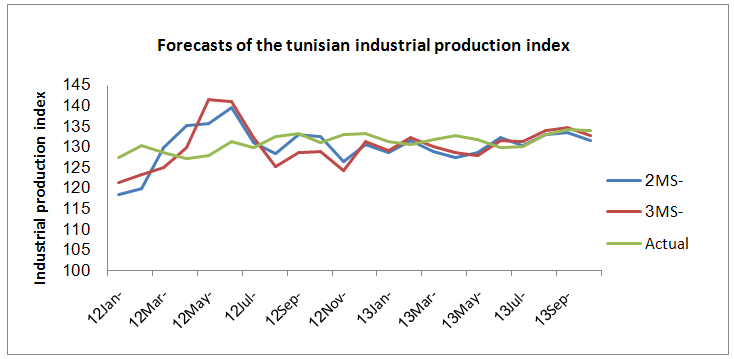

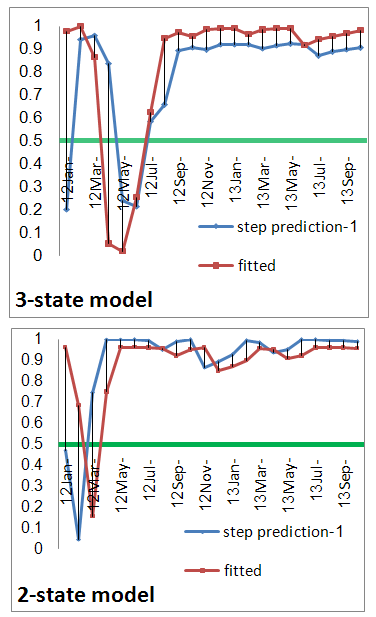

4. Forecasting

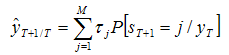

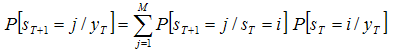

- After estimating the switching regime models, in order to analyse the economic activity in Tunisia, we are now interesting at the ability of the Markov switching models to forecast the industrial production in Tunisia. To do this, we consider two different Markov switching models: the two state as well as the three state models11. Our objective is to determine the best forecasting model of the economic activity in Tunisia.To establish a comparison between two models, we have had recourse to the following out-of-sample forecasting procedure12.Out-of-sample forecastingWe estimate the model for the period ranging from2000:01 up to 2011:12, and then, we use a recursive out-of-sample procedure from 2012:01 to 2013:10.To obtain the forecasts we should determine at each period the intercept and the predicted filtered probabilities one step ahead. At the first date of forecasting T + 1=2012:01, we have the following expression:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| Figure 3. Forecasts of the tunisian industrial production index |

| Figure 4. Fitted and 1-step predicted probabilities |

|

5. Conclusions

- This study uses Markov switching models for estimating, dating and forecasting the economic activity in Tunisia during the two last decades. In particular, the optimal probabilities interferences determined from the Markov switching models are used to define the different phases of the cyclical economic fluctuations emphasizing the Tunisian real production. In fact, in this paper we estimate a three regime Markov switching model for monthly industrial production growth rate over the period 2000–2012, in which the intercept and the variance are allowed to vary given the state of the economy. The specification tests show that the Markov switching model is a powerful technique for analysing the Tunisian business cycle. And the parametric steepness test of asymmetry suggests that the three regime Markov switching model represents the Tunisian economic activity better than the two regime model.On the other side, we conclude that the non linear three state Markov switching model displays a better out-of-sample forecasting performance than the two state Markov switching model. This conclusion has been confirmed when using a comparison based on the predictive performance of the two and three-state models. In fact, the filtered probabilities from the switching regime models allow us to obtain forecasts very close to the reality and to prefer the three-state model. Moreover, to recognize in advance the economic transition relating to a new phase of the economic cycle, we can consider the Markov switching models as an adequate tool able to determine the dating evaluation of the economic cycles, so as to present the forecasts concerning the real economic activity fluctuations in Tunisia.

Notes

- 1. Keynes has indicated that the time series "unemployment" is characterised by sudden jumps.2. In fact, our ultimate objective is to analyse the cyclical asymmetries. The Markov switching models are known for their empirical success to analyse such asymmetries mainly during the analysis of the American economic series such as the gross national product.3. This model can also be called three regime Markov intercept heteroscedasticity autoregressive model noted MSIH (3)-AR (p).4. In most of the works concerning the business cycle asymmetries, we use the industrial production series as a reference series. 5. For estimation purposes, as time series concerning the period under our review is not stationary, we consider the 12-month growth rates series in order to exclude the short-term fluctuations.6. Ferrara (2003) has pointed that the presence of lags deteriorates the reproduction of the stylized facts of the cycles.7. All estimations are done by using the GiveWin2 software.8. Clements and Klorzig (2003) have proved that for the two state Markov switching model the time series is non-steep. 9. Since there are no lags for the autoregressive parameters in our model, the Markov Switching Mean model is equivalent to the Markov Switching Intercept model.10. These rules have been also considered by Medhioub and El Euch (2013) in detecting turning points by correlation function.11. In fact, while estimating these two models, we have rejected the linearity hypothesis. So, we fine it pointless to use linear models for the comparison of the forecasts obtained by the linear and non linear models.12. We apply the same procedure for the two models.13. For both models, we obtain the same phase of economic activity when the fitted and predictive probabilities are greater (or lesser) than 0.5.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML