Joseph T. Crouse

Vocational Economics, Inc., Louisville, USA

Correspondence to: Joseph T. Crouse , Vocational Economics, Inc., Louisville, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

To date, the literature on estimating tuition elasticities has been narrowly focused by analyzing primarily four-year universities. We use data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) on all United States public 2-year colleges from 2004 to 2011 and examine the tuition elasticity of enrollment across the four major U.S. Census regions. By examining the tuition elasticity of enrollment for two-year public colleges, this paper helps to fill the under-researched aspect of how tuition levels influence campus enrollments at community colleges where the mission is to serve the greatest number of students in the community at an affordable cost. Empirical evidence presented here suggests that the nationwide tuition elasticity of total enrollment is -0.263. At the mean, a $100 increase in tuition and fees would lead to a decline in enrollment of about 0.883%. We find considerable differences across regional tuition elasticity of enrollment. Our results suggest that community colleges are normal goods and substitutes to four-year institutions. We consider the distribution of tuition increases among income groups and find that tuition increases are regressive. Lastly, we find that competition between border counties plays an essential role in determining the effects of tuition increases.

Keywords:

Tuition, Enrollment, Educational attainment, Border effects

Cite this paper: Joseph T. Crouse , Estimating the Average Tuition Elasticity of Enrollment for Two-Year Public Colleges, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 5 No. 3, 2015, pp. 303-314. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20150503.01.

1. Introduction

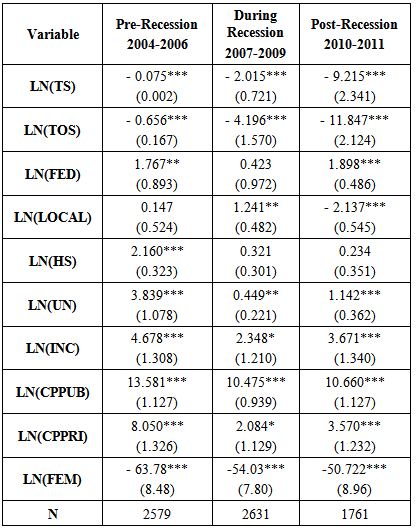

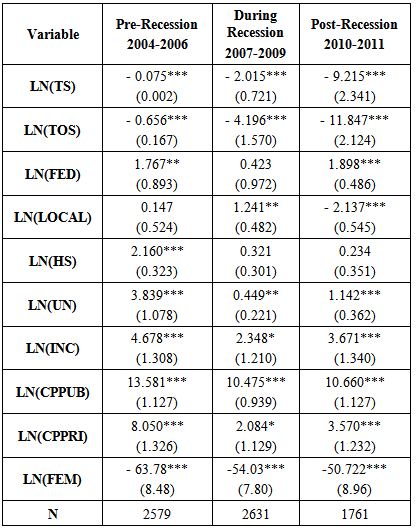

According to California Community Colleges Chancellor Jack Scott, California community colleges have shed more than 300,000 students since 2009 because the students cannot get into classes, and the toll is likely to grow unless the state reverses course and pumps more money into higher education (Los Angeles Times, 2012). Community colleges are primarily funded through state appropriations, and secondarily through tuition and fees that students pay as well as local funds (such as property taxes). Figure 1 presents the revenue sources that funded community colleges in 2009. | Figure 1. Revenue Sources – Public Community Colleges (Source: American Association of Community Colleges, 2009) |

As state appropriations are decreasing, it is of critical importance to understand the relationship between tuition and student enrollment. Since the goal of community colleges is to serve the greatest number of students at an affordable cost, the tuition elasticity of enrollment is important for policymaking considerations. A wide literature exists in educational finance which examines issues such as: the relationship between state appropriations and tuition, differences between private versus public educational structures, the return to education, and tuition elasticity. A large majority of this literature is focused solely on four-year universities and colleges, and neglects the salience that two-year colleges will play in the future of postsecondary education. Recently, Hemelt & Marcotte (2011) [1] examined the relationship between rising tuition and enrollment in four-year colleges and found an average tuition and fee elasticity of -0.1072% meaning that a $100 increase in tuition and fees would lead to a decline in enrollment of a little more than 0.25 percent (we include both elasticity measures and the effect on enrollment for a $100 change in real 2011 dollars (inflation adjusted) for ease of comparison with our studies). This paper represents a unique contribution to the existing literature in that the tuition elasticity of enrollment for two-year public universities is examined.Community colleges play a significant role in U.S. higher education. They offer an opportunity to receive a postsecondary education to many students who would not have attended college otherwise. Today, the number of U.S. undergraduates is at an all-time high as more and more people understand the necessity of having higher education in our technology-intensive world. Community colleges are very important in helping to absorb this increasing number of students. In addition, historically, college enrollments in general go up during times of economic downturns. Currently, community colleges have an additional appeal because tuition and fees at four-year colleges continue to increase while financial aid and student loans are getting harder to secure. For many students, community colleges offer the best chance to obtain a college education (Kolesnikova & Shimek, 2008) [2]. Every state offers two-year colleges as the first rung on the ladder of higher education and their importance is growing as fewer students are able to afford four-year universities (Shafer, 2008) [3]. States are currently faced with a substantial challenge in funding their two-year institutions: they must consider whether to increase tuition in order to offset the decreased state appropriations. Most states are answering this dilemma by increasing tuition. However, by increasing tuition community colleges may fail to meet their mission to the community: “…the mission of the community college is to provide access to postsecondary education programs and services that lead to stronger and more vital communities” (Vaughan, 2006) [4].Due to the specific mission of community colleges—to provide low cost affordable education to students of the surrounding communities that lead to placement into jobs or four-year institutions—this paper represents an important contribution with policy implications. If the tuition elasticity of enrollment for two-year public universities is higher than four-year universities or is elastic, this may indicate that community colleges are not fulfilling their missions to the states that they serve. As a matter of public policy, demand functions at public institutions are of primary concern. In the next section, we briefly review the literature on the relationship between tuition costs and enrollment in higher education. We then describe our empirical objectives and estimation strategy, along with describing the data that we utilize. We then examine the tuition elasticity of enrollment for two year colleges nationwide and then also consider the elasticities in each of the four U.S. Census regions to better understand regional effects. We also examine whether community colleges are an inferior good in each region by looking at the regional income elasticities of enrollment. Finally, we consider further work that may extend our research and conclude with policy implications derived from our study.

2. Literature Review

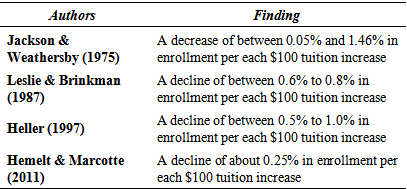

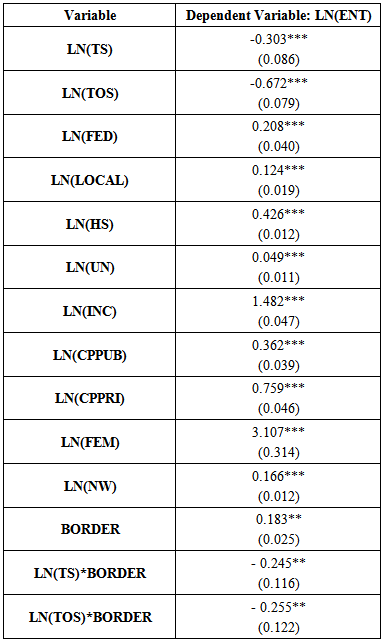

Economists and policy-makers have long been interested in understanding the demand for higher education. Studies focused on quantifying price elasticities for various student populations, estimating student sensitivity to changes in financial aid packages, and constructing demand functions are examples of such work. The literature on higher education has been almost exclusively concerned with four-year colleges and universities and has neglected an analysis of the market for community colleges. Table 1 presents the previous findings for the tuition elasticity of enrollment at public four-year educational institutions. The previous findings range from an elasticity of -0.05% to -1.46% (Jackson & Weathersby, 1975; Leslie & Brinkman, 1987; Heller, 1997; Hemelt & Marcotte, 2011) [5-7]. The only published study that considers two-year colleges that is known to the author finds that a $1000 increase in public two-year tuition is estimated to result in a 3.5 percentage point drop in total public undergraduate enrollment (both two-year and four-year enrollment within a state). This study is limited though in that it lumps the enrollment response of both two-year and four-year enrollment together and does not allow for a precise estimation of the two-year tuition elasticity of enrollment (Kane & Rouse, 1999) [8]. Table 1. Previous Findings of Tuition Elasticity of Enrollment for 4-year Educational Institutions

|

| |

|

No other countries but the United States and Canada have formed comprehensive community colleges. The primary reason is that compulsory education continues for a greater number of years for American youth than it does in any other nation, a phenomenon seeding the desire for more schooling. The second reason is that Americans seem more determined to allow individual options to remain open for as long as each person’s motivations and the community’s budget allow. Placing pre-baccalaureate, vocational, and developmental education within the same institution enables students to move from one to the other more readily than if they had to change schools. The decision to enroll in a two-year institution is a factor of increased individual options as much as one of cost and affordability (Rouse, 1994) [9]. We will test the hypothesis that community colleges are normal goods and serve a higher purpose than as a cheaper alternative to four-year colleges. Changes in macroeconomic activity impact college enrollment significantly. During periods of declining economic growth, there are fewer jobs to be found that do not require a collegiate education. Enrollment decisions in four-year universities are significantly impacted by changes in macroeconomic activity, but two-year colleges may be impacted even more so since vocational and trade programs are also available through the community colleges (Ewing, Beckert & Ewing, 2010) [10]. When the United States experiences decreasing macroeconomic activity, the level of state appropriations for higher education decreases in most state budgets. The decline in state appropriations leads policymakers to consider whether to increase tuition in order to fund more classes or programs or to find other revenue sources through an increase in local property taxes, for instance. Koshal & Koshal (2000) find that four-year tuition depends upon state appropriation, median family income, out of state enrollment as a percentage of total enrollment, and the region that a particular state is located. Additionally, state appropriation is affected by the level of tuition, per-capita tax revenue, demand factor, 2-year college enrollment as a percentage of total enrollments, and the clear majority of democrats in the state legislature. The results also indicate a clear interdependence of tuition and appropriation at the public institutions in the United States (Koshal & Koshal, 2000) [11]. One way that community colleges are able to increase tuition and meet their mission to serve the greatest number of students in the community at an affordable cost is to increase the tuition for out-of-district students as well as out-of-state students (Rizzo & Ehrenberg, 2003) [12]. Analogous to four-year universities increasing the burden of tuition on out-of-state students, two-year universities may engage in this practice by raising the out-of-district tuition and holding in-district tuition constant.Community colleges have played a salient role in higher education for the last several decades and will continue to play an important role in providing access to higher education to those needing a more affordable and flexible alternative to their four-year counterparts. Although there persists a widespread skepticism regarding the value of a community college education, empirical estimates have shown that the estimated returns to college credits at two-year and four-year institutions are remarkably similar. Namely, there is an approximately four to six percentage increase in annual earnings for every two semesters (30 completed credits) of college education, whether completed at a two-year or four-year institution (Kane & Rouse, 1998) [13]. This finding comes from utilizing NLS-72 and NLSY79 data to estimate the labor market returns to two- and four-year institutions of higher education. As a result, it may be that similar returns to two- and four-year college credits exist because students decide at the margin between the two types of institutions. The objective of this paper is to explicitly consider the various elasticities of enrollment associated with two-year public colleges and derive results for policy consideration.

3. Data & Empirical Methodology

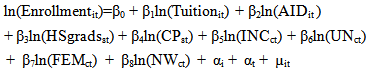

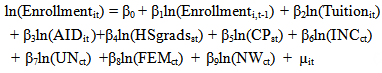

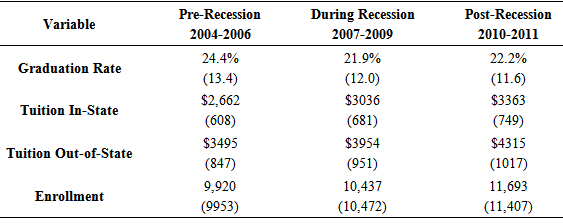

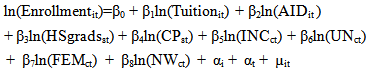

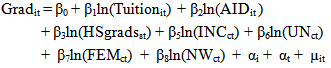

In this paper we review recent trends in tuition at two-year public colleges and estimate the impacts on enrollment. We utilize data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) on public two-year colleges from the 2003-2004 academic year to the 2010-2011 academic year. The impacts of these tuition increases on total enrollment and credit hours are assessed. We estimate the average tuition and fee elasticity of enrollment (measured by both total headcount and credit hours). The income elasticity of enrollment is also considered in determining whether community colleges are normal goods. Both policy implications and the mission of community colleges are carefully and critically discussed in relation to our results. Our model is specified as follows:  | (1) |

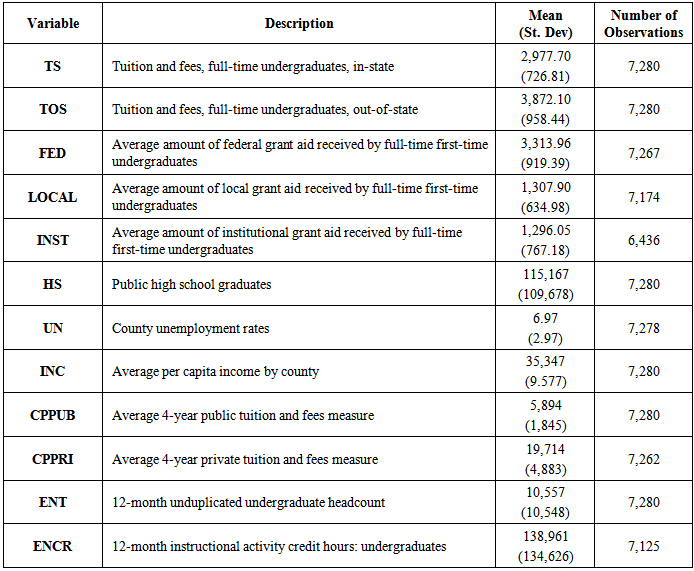

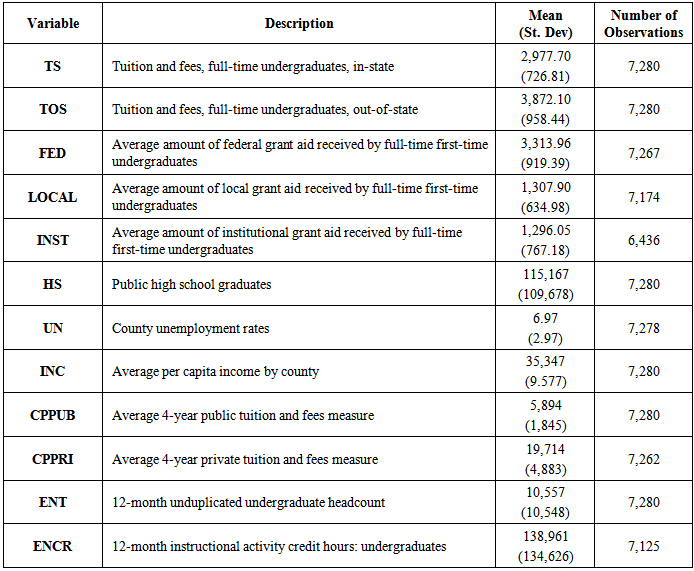

where Enrollmentit is the enrollment in institution i during the academic year t. Two measures of enrollment are used as the dependent variable: the 12-month unduplicated headcount of all students enrolled as well as the total number of credit hours. Tuitionit represents two measures of tuition and fees in the institution i during the academic year t charged for full-time students at community colleges: one is the in-state tuition and fees, and the second is the out-of-state tuition and fees. AIDit is a measure of the average amount of federal grant a received by full-time first-time undergraduates as well as the average amount of state/local grant aid received by full-time first-time undergraduates. In order to control for institutional and state factors that affect enrollment in a given period, the following controls are included: HSgradsst is a measure of the number of high school graduates in state s in academic year t, CPst includes two measures of competitor’s prices which include the average tuition and fees charged for full-time students attending 4-year public universities and 4-year private universities for a given state s in academic year t, INCct is a measure of the average per capita income in county c in year t and UNct is a measure of unemployment in county c in year t. Demographic controls are also included where FEMct is a gender control variable that measures the percentage of women in county c in year t, and NWct is a race control variable that measures the percentage of non-whites in county c in year t. Institutional-specific fixed effects (αi) and time fixed effects (αt ) are also included in the model. It is important to note that the number of high school graduates and competitor prices are readily available only at the state level, whereas data can be easily obtained at the county level for per capita income, unemployment, percentage of females, and percentage of non-whites.Two critical assumptions in our model are that: tuition increases are largely exogenous at the institutional level and schools have limited power to affect admission decisions when adopting tuition increases. This second assumption need not hold at the community college level since admissions are open and non-selective. That is, the institutional officials cannot decide to become less selective in order to offset the revenue loss from a tuition increase. There is not a selective process in public community colleges. We conduct a Granger causality test in order to defend our first assumption in this model. In testing whether enrollment Granger causes tuition, we fail to reject the null hypothesis of no Granger causality. Thus, reverse causality is not a problem in our model. In testing whether tuition Granger causes enrollment, we reject the null hypothesis of no Granger causality in favor of the alternative that tuition does, indeed Granger cause enrollment at the 99% confidence level. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of our key dependent and independent variables. The average in-state tuition and fees per academic year for our sample was $2,977.70 (all tuition figures are reported in real 2011 dollars by utilizing the GDP deflator). The average out-of-state tuition and fees per academic year for our sample was approximately 30% higher at $3,872.10. This shows that states do, in fact, charge a premium for out-of-state students in order to fund the community colleges while also meeting their key mission. It is important to note that the average tuition for public 4-year universities was $5,894 which is nearly double the tuition of the average community college. The average private university tuition and fees was $19,714 which is over six times the cost of an in-district community college. The average community college had a 12-month unduplicated headcount of 10,557 students. A measure of the credit hour activity is also an important measure in determining enrollment. The average community college had students enrolled in 138,961 credit hours.Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for Key Variables (2004-2011)

|

| |

|

We are also interested in estimating the regional tuition elasticities, so we utilize the four major Census regions as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Our sample includes 902 observations from the Northeast, 1,735 from the West, 1,613 from the Midwest, and 2,721 from the South. An inspection of the scatter diagrams displaying the relationship between the logarithms of in-state tuition to the logarithms of total enrollment reveals that in each region, it appears higher in-state tuition is associated with a lower enrollment. Our regression analysis in the next section will present the determinants of total enrollment in each region and we will discuss the impact that an increase in the in-state tuition has on total enrollment in each of the respective regions.

4. Empirical Results

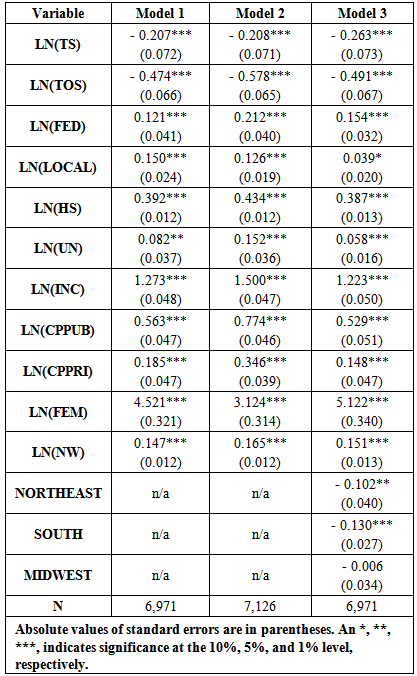

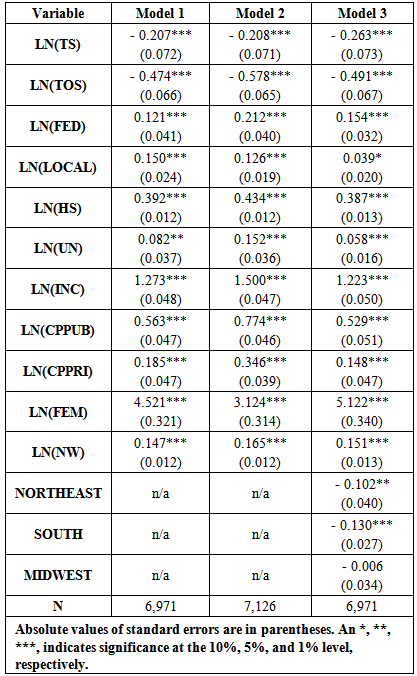

In order to more fully understand the relationship between tuition increases and enrollment, we present our multivariate regression results in Table 3. We consider Model 1 with the logarithm of total credit hours as the dependent variable and Model 2 with the logarithm of student enrollment as the dependent variable. We find all variables of interest to be significant at the 1% level of significance in both models. Model 3 utilizes the logarithm of total credit hour enrollment as the dependent variable and includes regional effects to isolate the differences between regions across the United States and control for the effect that regional differences may have on the tuition elasticity of enrollment. We concentrate our discussion on the results that utilize credit-hour enrollment as the dependent variable since this measure better reflects the substantive enrollment towards degree progression. Table 3. Main Regression Results

|

| |

|

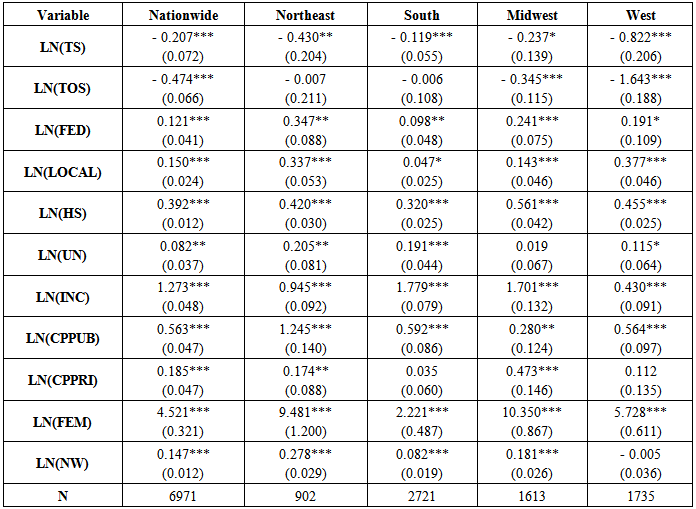

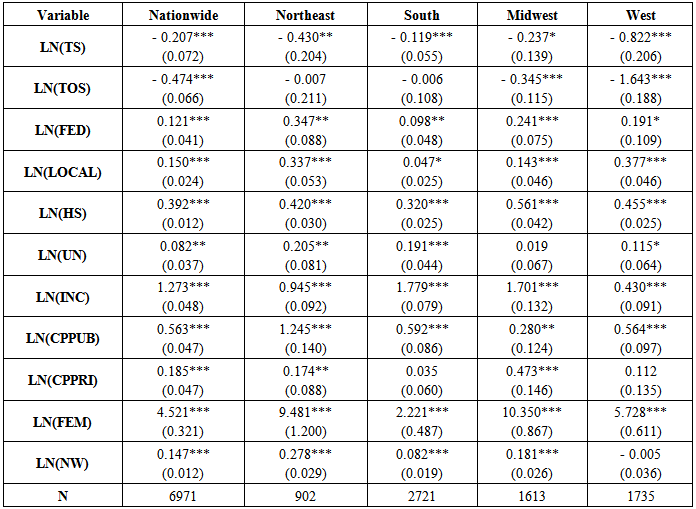

We find that a 1% increase in in-state tuition leads to a 0.207% decline in total community college enrollment (measured in credit hours). We also find that a 1% increase in out-of-state tuition leads to a 0.474% decrease in total community college enrollment (measured in credit hours). This is most likely because if a community college attracts out-of-district students over an in-district community college, it must offer unique programs and better opportunities so that students would be less enticed to leave with a tuition increase. When federal aid available to students goes up by 1%, we find that community college enrollment increases by 0.121% which makes intuitive sense since community colleges are now more affordable. In response to a 1% increase in local aid, total credit hour enrollment increases by 0.150%. Also, we find that community colleges are both a normal good as well as a luxury good. As the average per capita income increases by 1%, we find a 1.273% increase in community college enrollment. This result is most likely due to the fact that a portion of community college enrollment stems from the unique opportunities and choices that community colleges present which four-year institutions do not offer. For instance, at a community college a student can easily move between a beauty school program, a nursing program, a technical program, and liberal arts studies in preparation for a four-year institution. Lastly, we find that as the average four-year public university tuition increases by 1%, the enrollment in community colleges increases by 0.563%. Similarly, as the average four-year private university tuition increases by 1%, the enrollment in community college increases by 0.185%. This suggests that public and private four-year institutions are substitutes for community colleges and relevant competitors to two-year institutions. Private institutions are weaker substitutes for community colleges than public four-year institutions. This conforms to the intuition that private institutions serve a more elite student in general and may have more scholarship endowments. Model 3 presents our regression results with regional effects and we find that a 1% increase in in-state tuition leads to a 0.263% decline in community college credit hour enrollment. These results are not substantially different from those presented in Models 1 and 2 without regional effects.We run four separate regressions across regions in order to examine the specific regional differences and compare the estimates. Table 4 presents our estimates across regions and our nationwide estimates are reproduced for ease of comparison. We find that the enrollment responsiveness to in-state tuition increases is the largest in the West at approximately – 0.822%. We find that the enrollment responsiveness to in-state tuition increases in the Northeast, South, and Midwest are -0.430%, -0.119%, and -0.237%, respectively. Clearly there appear to be significant regional differences though the reason remains unclear. One possible explanation could be that the cost of living in the Northeast and West is higher for students than in the Midwest and South. As a result, we would expect students to be more responsive to changes in tuition in the Northeast and West since their budgets are being further extended to pay for higher housing costs. The income elasticity of enrollment is positive and significant in each region, suggesting that community colleges are normal goods. We find that the income elasticity of enrollment in the Northeast, South, Midwest, and West are 0.945%, 1.779%, 1.701%, and 0.430%, respectively. The income elasticity is the lowest in the West whereas the price elasticity if the highest. Table 4. Estimates across Regions (Logarithm of ENCR is dependent variable)

|

| |

|

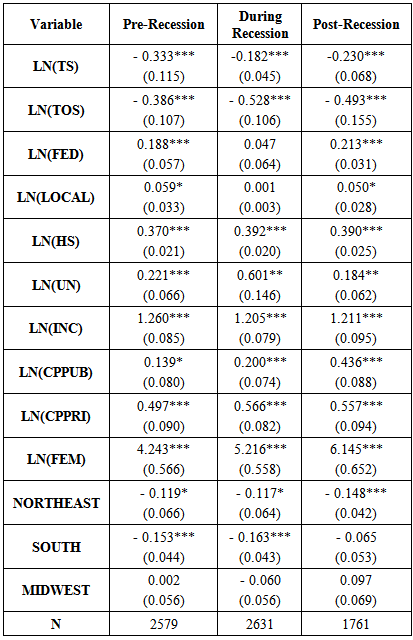

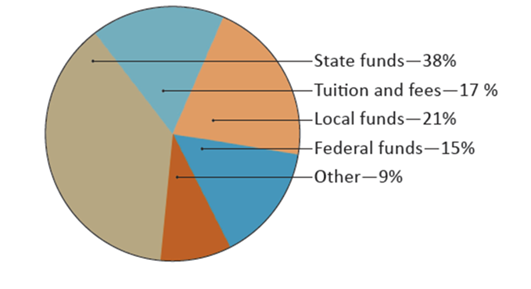

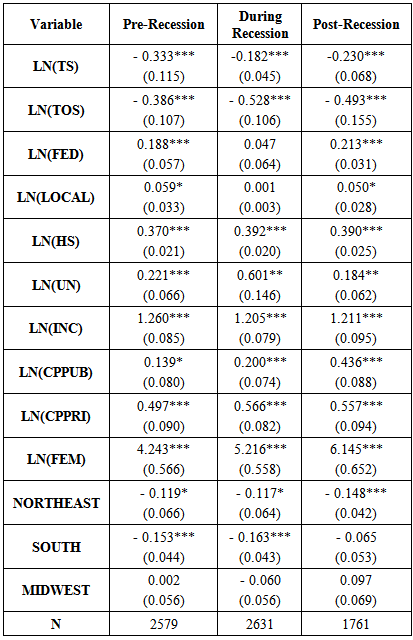

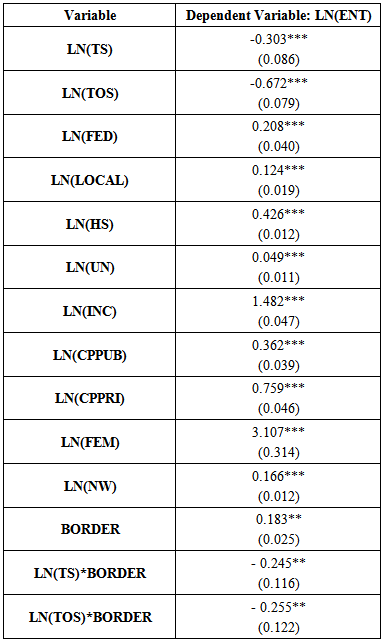

We also derive interesting demographic conclusions across regions. As non-whites increase by 1% in a given state, we find that the community college enrollment increases by 0.278% in the Northeast, 0.082% in the South, and 0.181% in the Midwest. The effect in the West is not significantly different from zero. In each region we find that as the percentage of females in a state increases, the enrollment correspondingly increases with an elastic responsiveness.Lastly, in Table 5 we present we present our regression results over time to see how the economic recession that the U.S. experienced between 2007 and 2009 impacted the tuition elasticity of enrollment. The in-state tuition elasticity of enrollment was -0.333, -0.182, and -0.230 during the pre-recessionary, recession, and post-recessionary periods, respectively. These elasticity estimates conform with the intuition that during recessionary periods, individuals become less responsive to tuition increases due to the need to obtain job-marketable skills to remain competitive in the labor market while unemployment rises. We also find that federal aid and local aid are insignificant predictors of community college enrollment during a recessionary period. Lastly, the income elasticities of enrollment remain remarkably constant over time at 1.260, 1.205, and 1.211 for pre-, during, and post-recessionary periods, respectively.Table 5. Estimates across Regions (Logarithm of ENCR is dependent variable)

|

| |

|

4.1. Robustness Checks

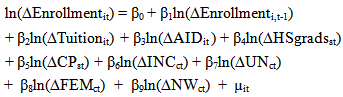

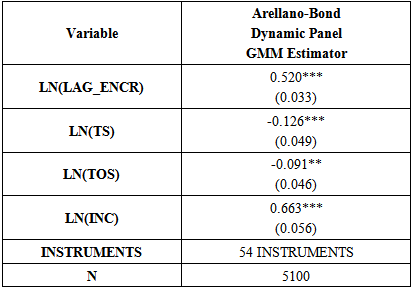

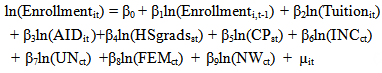

We also utilize the Arellano-Bond dynamic panel GMM estimator to cope with several potential econometric problems: the simultaneous causality leading the endogenous regressor (tuition) to be correlated with the error term; the time invariant institutional characteristics may be correlated with the error term; the autocorrelation that results from properly taking into account the enrollment level in the previous period; and the small time dimension and larger institutional dimension. Our base specification econometric model including a lag of the total enrollment level is: | (2) |

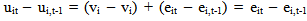

Several econometric problems arise from estimating equation (2). First, the tuition variable, Tuitionit, is endogenous because causality may run in both directions leading the regressors to be correlated with the error term (the Granger causality test suggested that this is not the case, but we still recognize that the reverse causality could be a problem). The time invariant institutional characteristics (fixed effects) may be correlated with the explanatory variables. The fixed effects are contained in the error term in equation (2), which consists of unobserved institution-specific effects, vi, and the observation-specific errors, eit:  | (3) |

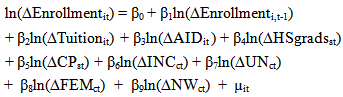

Another problem in estimating (2) is that the presence of the lagged dependent variable, Enrollmenti,t-1, gives rise to autocorrelation. Lastly, the panel dataset has a short time dimension (T=8) and a larger institution dimension (N=910). In order to solve the first problem, we could have utilized fixed-effects instrumental variables estimation (two-stage least squares). However, the strength of the instruments can always be improved since weak instruments cause the fixed-effects IV estimators to be likely biased in the way of the OLS estimators. In order to increase the strength of the instruments and thereby minimize the biasedness of the estimators, we utilize the Arellano-Bond (1991) difference GMM estimator first proposed by Holtz-Eakin, Newey & Rosen (1988) [14]. We utilize lagged levels of the endogenous regressors as instrumental variables. This makes the endogenous variables pre-determined and, therefore, uncorrelated with the error term in equation (2). In order to cope with the second problem (fixed effects), the difference GMM uses first-differences to transform equation (2) into: | (4) |

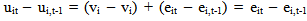

By transforming the regressors by first differencing the fixed institutional-specific effect is removed, because it does not vary with time. From equation (3) we obtain: | (5) |

| (6) |

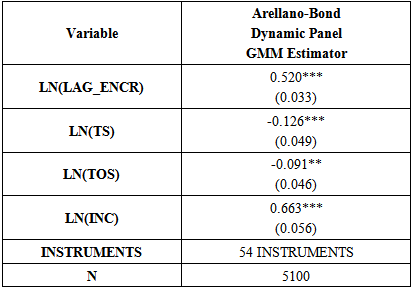

The first differenced lagged dependent variable is also instrumented with its past levels in the Arellano-Bond dynamic panel specification. Lastly, the Arellano-Bond estimator was designed for when the panel dataset has a short time dimension and a larger institution dimension (small-T large-N panels). In small-T panels a shock to the university’s fixed effect, which shows in the error term, will not decline with time. Similarly, the correlation of the lagged dependent variable with the error term will be significant. In these cases, the Arellano-Bond estimator is preferred over the fixed-effects IV estimators. We present our key results utilizing the Arellano-Bond dynamic panel generalized method of moments estimator in Table 6. The coefficient estimates for the lag of enrollment, in-state tuition, federal aid, unemployment, and per capita income are significant at the 1% level. Only the percentage of females and the percentage of non-whites are insignificant predictors of enrollment in this specification. We find that a 1% increase in enrollment in the previous period persists into the current period and leads to a 0.520% increase in enrollment in the current period. The in-state tuition elasticity of enrollment is – 0.126% and the income elasticity of enrollment is 0.663%. These results are similar in sign, though smaller in magnitude, to what we found in Table 3 with university-level fixed effects. Community college enrollment is no longer a luxury in this specification which makes more economic sense. These coefficient estimates are most similar to those reported in Table 1 that previous research has suggested for four-year universities.Table 6. Arellano-Bond Estimator Regression Key Results

|

| |

|

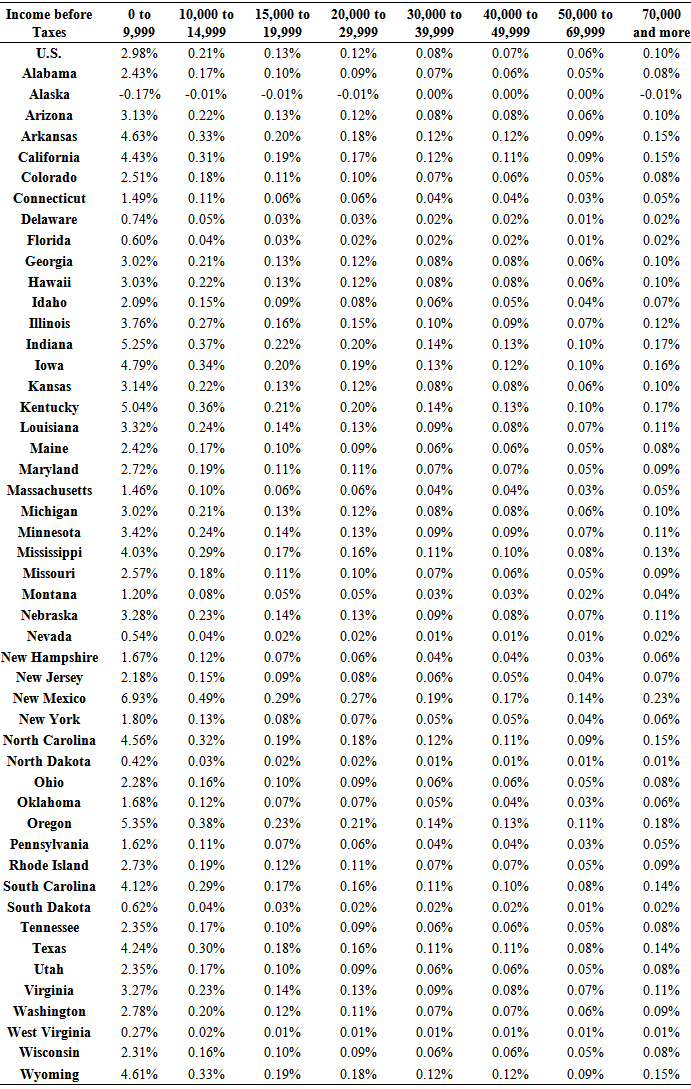

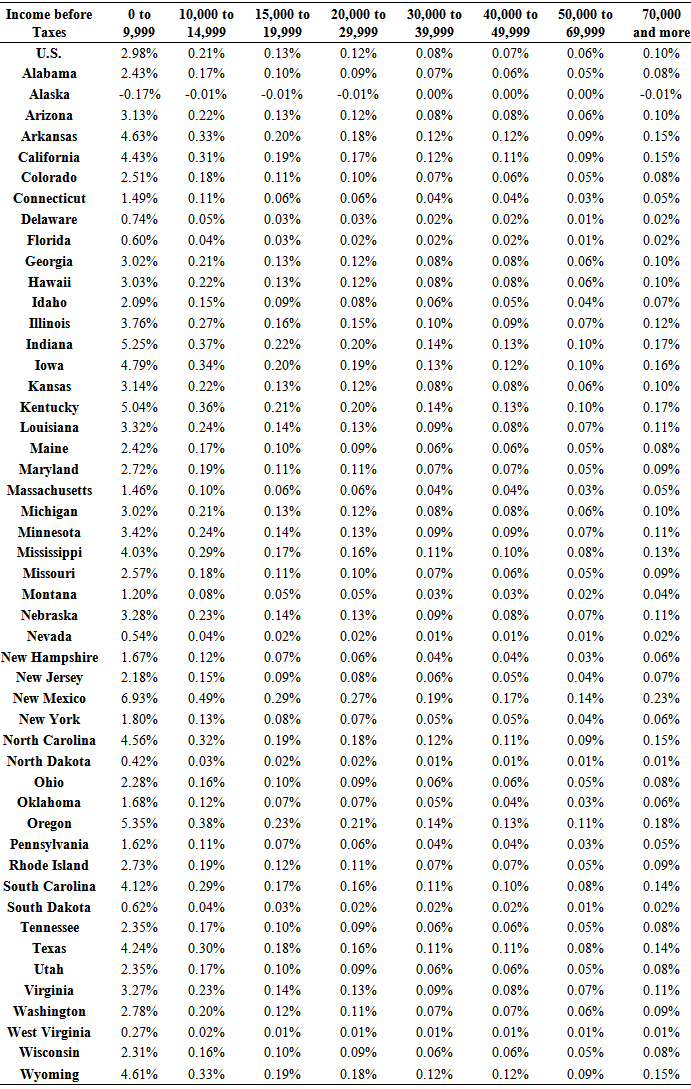

4.2. Incidence Analysis: Distribution of Tuition Increases among Income Groups

The annual Grapevine report from the Center for the Study of Education Policy at Illinois State University concluded that 41 states reduced their state funding for higher education as a result of the slow economic recovery and the end of federal stimulus funds in recent years. As state appropriations decline, universities place more of the financial burden on students by increasing tuition. The statutory incidence of a tuition increase refers to the distribution of tuition payments based on the obligation to remit tuition payments to a university. We focus on economic incidence which measures the change in economic welfare arising from a tuition increase. Statutory and economic incidence differ because the latter considers how tuition increases affect equilibrium decision making and how those changes affect different kinds of individuals. We examine the efficiency and equity implications of the results by including an incidence analysis where we consider who ultimately bears the burden of tuition increases in the community college environment. We utilize data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX) 2011 in order to provide a rough estimation of the distribution of tuition increases among income groups. In order to consider the economic incidence, we must first compute the share of education expenditure by income group. This is done by multiplying the educational expense in a given income group by the number of consumer units in that income group and dividing the product by the total educational expense across all consumer units. We multiply this result by the average tuition increase by state (in our sample period 2004-2011) and find the education share. Next, we compute the share of income by income group. This is accomplished by multiplying the income before taxes in a given income group by the number of consumer units in that income group and dividing the product by the total income before taxes across all consumer units. We multiply this result by the total personal income increase by state (in our sample period 2004-2011) and find the income share. Lastly, we divide the education share by the income share and report our results in Table 7 that indicate an approximate distribution of tuition increases among income groups. Table 7 provides a rough approximation of the distributive effects of a tuition increase. It appears that tuition increases for community colleges are regressive: individuals in higher income groups bear less of the burden of tuition increases than individuals in lower income groups. This may be partially driven by fewer individuals in high income groups attending community colleges and also because they can better afford it since their income has risen. Interestingly, we find that in Alaska the increase in tuition over the period 2004-2011 resulted in an enrollment that was not sufficient to increase total tuition revenue. The change in total tuition revenue was negative, leading to the negative numbers reported in our table. Our analysis provides only a rough estimation and should be interpreted with caution. We aggregated our analysis at the state level so that we could take variations across states into account rather than analyzing at the county-level where community colleges may be very geographically distributed in some areas. Mobility also obscures the incidence distribution since more people at the bottom of the income distribution may be dropping out of college. In addition, the individuals at the bottom of the income distribution fund their education primarily through financial aid, so their true educational out-of-pocket expense is much lower than what is estimated by the CEX data. Table 7. Distribution of Tuition Increases among Income Groups

|

| |

|

4.3. Educational Attainment

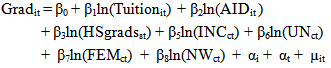

The main mission of every community college is to graduate the students that they enroll and place the students into careers within the surrounding community. It is important to better understand how educational attainment (measured in terms of graduation rates) is impacted by tuition changes. We utilize the same independent variables that explained enrollment in order to explain graduation rates. The graduation rate data comes from IPEDS and measures the total number of completers within 150% of normal time divided by the total number of students in the adjusted cohort. Our model is specified as follows: | (7) |

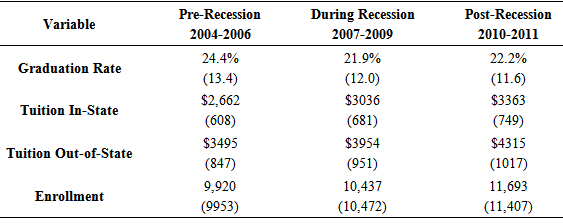

Table 8 presents the descriptive statistics for the graduation rates, in-state and out-of-state tuition, and enrollment pre-, during, and post-recessionary period.Table 8. Key Variables Pre-, During, and Post-Recessionary Period

|

| |

|

Table 8 shows that the graduation rate declined during the recessionary period from 24.4% to 21.9% while the in-state tuition, out-of-state tuition, and enrollment have steadily increased from 2004 to 2011. This makes sense since with fewer jobs students stayed in school longer. We seek to explain the factors affecting educational attainment (in terms of graduation rates) and Table 9 presents our educational attainment regression results.Table 9. Educational Attainment Results Pre-, During, and Post-Recession (Dependent variable: Graduation Rate)

|

| |

|

Table 9 indicates that the responsiveness of graduation rates to tuition changes increased during the recessionary period and dramatically increased following the recessionary period. During the recessionary period, if the in-state tuition increased by 1%, we would expect the graduation rates to have fallen by 2%. Following the recessionary period, the impact of tuition increases on graduation rates seems to be even larger at – 9% for every 1% increase in tuition. Human capital diffusion throughout the economy appears to be slowed both during and following the recessionary period. With increased tuition, community college students appear to take fewer classes and take longer to graduate.

4.4. Border Effects

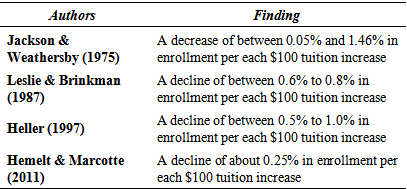

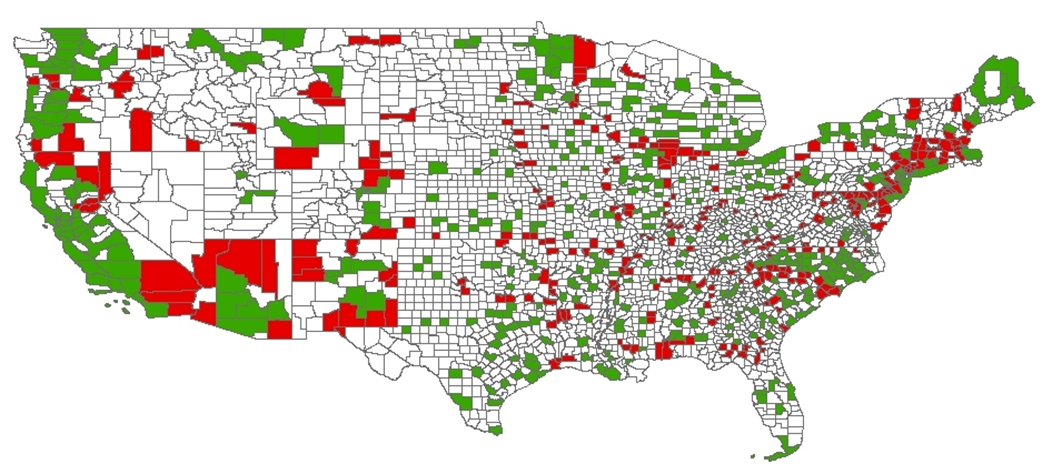

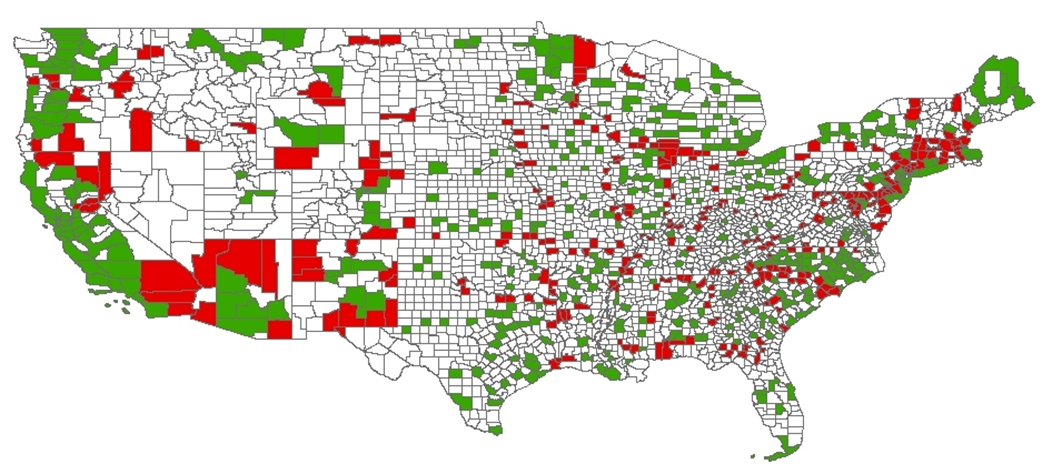

Lastly, we explore the effects of inter-state competition by including an interaction term where a border county dummy is interacted with our tuition variables. Of our 910 community colleges in our sample, 339 community colleges (37.3%) lie on the border of another state. We define our border county variable as a binary variable where it takes on a value of 1 if the county in which the community college is located lies on the border of another county in a different state. Figure 2 presents the counties where community colleges are located for the contiguous United States. Counties colored red indicate community colleges that lie along interstate borders and those colored green are counties that house community colleges that are not located along interstate borders. | Figure 2. Community Colleges that Lie on Inter-state Borders in the United States |

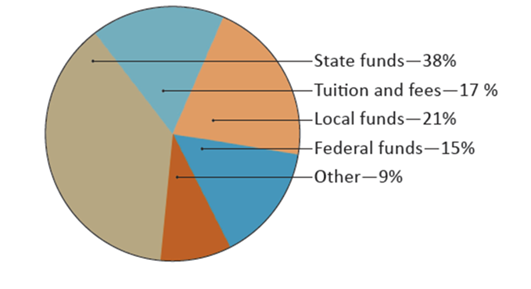

Table 10 presents our regression results with border effects. We find that both of the interaction terms with tuition interacted with our border dummy are significant at the 5% level. Non-border community colleges experience an average in-state tuition elasticity of - 0.303%, whereas the border community colleges experience a higher in-state tuition elasticity of - 0.548%. Similarly, non-border community colleges experience an average out-of-state tuition elasticity of - 0.672%, whereas the border community colleges experience a higher out-of-state tuition elasticity of - 0.972%. These tuition elasticities of enrollment show that the competition between border counties plays an essential role in determining the effects of tuition increases. Community colleges have a powerful incentive to keep their in-state tuition lower than a neighboring state’s out-of-state tuition if they are located on a border county because of the competition that prevails to enroll students.Table 10. Regression Results with Border Effects

|

| |

|

5. Conclusions

The most recent study of the average tuition elasticity of enrollment for four-year public universities found that a $100 increase in tuition and fees would lead to a decline in enrollment of about 0.25% (Hemelt & Marcotte, 2011). By utilizing our model with regional effects, we find that a $100 increase in tuition and fees would lead to a decline in enrollment of about 0.883%. A 1% increase in in-state tuition and fees is expected to lead to a 0.263% decline in credit-hour enrollment. Thus, we conclude that the enrollment responsiveness to increases in tuition is higher in community colleges than in four-year public institutions. In our study we also examined the in-state tuition elasticity of enrollment across the various Census regions and obtained estimates of - 0.430%, - 0.119%, - 0.237%, and – 0.822% for the Northeast, South, Midwest, and West, respectively. These estimates indicate that there are considerable differences in tuition responsiveness across regions. For instance, a policymaker in the West should expect relatively higher enrollment responsiveness to tuition increases than in the South where the elasticity is lower. We also find that community colleges are a normal good since, as the average per capita income increases by 1%, we find a 1.237% increase in community college enrollment. Community colleges offer unique opportunities and choices that four-year institutions do not, so it is not surprising that as income goes up, community college enrollment also increases. This suggests that the Arellano-Bond adjustment was important. If we look at this result across regions, we find that community colleges are a normal good in each of the Census regions. We find that community colleges are a substitute for both four year public and private universities.Human capital diffusion throughout the economy appears to be slowed both during and following the recessionary period. We find that during the recessionary period, if the in-state tuition increases by 1% we would expect graduation rates to fall by 2.015%. The estimates are more dramatic post-recession. With increased tuition, community college students appear to take fewer classes and take longer to graduate.In the future, our research on community colleges can be extended by considering how the tuition increases affect transfers to four-year colleges and universities. We may also consider, in a more in-depth framework, how tuition increases affect educational attainment, as the ultimate goal of higher education is to prepare students for the workforce and help them obtain suitable employment.Thus, our study has found tuition elasticities across each of the Census regions that may be used by policymakers to derive conclusions on how to finance their respective higher education systems. We also provided results that indicate community colleges are both normal goods and substitutes to four-year institutions in each Census region. We considered who ultimately bears the burden of tuition increases in the community college environment, and found that tuition increases are regressive. In addition, we find that graduation rates became more responsive to tuition changes following the recessionary period. Lastly, competition between border counties seems to play an essential role in determining the effects of tuition increases and provides an incentive for border counties to compete in setting tuition.

References

| [1] | Hemelt, S. W., & Marcotte, D. E. (2011). The impact of tuition increases on enrollment at public colleges and universities. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(4), 435-457. |

| [2] | Kolesnikova, N., & Shimek, L. (2008, October). Community colleges: Not so junior anymore. The Regional Economist, 6-11. |

| [3] | Shafer, D. (2008, May). The States and Their Community Colleges. The Rockefeller Institute, Education Policy Brief. |

| [4] | Vaughan, G. B. (2006). The community college story (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges. |

| [5] | Jackson, G. A., & Weathersby, G. B. (1975). Individual demand for higher education: A review and analysis of recent empirical studies. The Journal of Higher Education, v. 46(6), pp. 623-651. |

| [6] | Leslie, L. L., and Brinkman, P. T. (1987). Student price response in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 58, 181-204. |

| [7] | Heller, D.E. (1997). Student price response in higher education: An update to Leslie and Brinkman. Journal of Higher Education, 68(6), 624-659. |

| [8] | Kane, Thomas J., and Cecilia Elena Rouse (1999). The Community College: Educating Students at the Margin between College and Work. Journal of Economic Perspectives 13, 63-84. |

| [9] | Rouse, C. E. (1994). What to do after high school: The two-year versus four-year college enrollment decision. In R. G. Ehrenberg (Ed.), Choices and consequences: Contemporary policy issues in education (pp. 59-88). Ithaca, NY: ILR Press. |

| [10] | Ewing, K. M., Beckert, K. A., & Ewing, B. T. (2010). The response of US college enrollment to unexpected changes in macroeconomic activity. Education Economics, 18(4), 423-434. |

| [11] | Koshal, R. K., & Koshal, M. (2000). State appropriation and higher education tuition: What is the relationship? Education Economics, v. 8(1), pp. 81-89. |

| [12] | Rizzo, M. & Ehrenberg, R. G. (2003). “Resident and nonresident tuition and enrollment at flagship state universities.” NBER Working Paper Series, No. 9916. |

| [13] | Kane, Thomas J. and Cecilia Elena Rouse. (1998). Labor Market Returns to Two and Four Year College. American Economics Review, 85, 3-24. |

| [14] | Holtz-Eakin, D., W. Newey & H.S. Rosen (1988). Estimating vector autoregressions with panel data. Econometrica 56: 1371-1395. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML