Qing Hu

Graduate School of Economics, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan

Correspondence to: Qing Hu, Graduate School of Economics, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

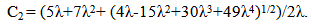

We consider a multiproduct firm that serves two markets. It monopolizes one market but competes with another firm in another market. We analyze the incentive for the multiproduct firm to bundle the monopolized product and the product of the competitive market. Based on the assumption that consumers’ preferences depend on “firm” rather than “product”, we show different results from the previous work. When the consumers’ reservation price is relatively low, bundling is not preferred. However, if the reservation price is relatively high, bundling happens for the purpose to foreclose the market and the multiproduct firm can earn monopoly profit in both markets.

Keywords:

Bundling, Multiproduct firm, Reservation price

Cite this paper: Qing Hu, Reservation Price and Bundling for a Multiproduct Monopoly, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 37-42. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20150501.05.

1. Introduction

Generally, considering bundling, there are two ways to bundle. One is “mixed bundling”, where consumers can buy a single product, but the firm will offer discounts if consumers buy its several products together. The other one is “pure bundling”, where firms only offer products in fixed proportions, such as that a portable game console and a game sold in a single box, and consumers cannot buy a single item. It is always in discussion about the legal application of bundling for a multiproduct monopoly, since the multiproduct firm may leverage its monopoly power to its competitive market by bundling. As an example in the reality, in Japan, Microsoft monopolizes the spreadsheet market (Excel) but competes with Ichitaro in the word processor market. Microsoft sells its word processor and spreadsheet in an office suite (pure bundling). Japan Fair Trade Commission recommended ceasing this Microsoft’s bundling. It is easy to imagine that for those consumers that have strong taste towards spreadsheet of Microsoft, pure bundling may force them to buy word processor from Microsoft as well. Moreover, we can understand that mixed bundling is weaker on this point because consumers who prefer to Ichitaro’s word processor can even choose to buy only spreadsheet from Microsoft under mixed bundling. Therefore we can imagine that the effect of leveraging the monopoly power is stronger under pure bundling. Many previous studies proved our thought.Peitz (2008) showed built a modified two-dimensional Hotelling model, and he assumed that firms chose prices simultaneously. The multiproduct monopoly could blockade entry in one certain market by pure bundling. Thus if the entry has occurred, then pure bundling is preferred. It is easy to understand that pure bundling strengthens the multiproduct firm for the leverage power explained above. Moreover, consumers’ reservation price was assumed as 1 and many consumers could afford the bundle under this level. Nalebuff (2004) showed that in a two-dimensional Hotelling model, if the multiproduct incumbent chooses prices before the entrant, it could deter entry by pure bundling. Whinston (1990) argued that the multiproduct firm considered mixed-bundling was indifferent from independent pricing, thus mixed-bundling is not effective to leverage the monopoly power to the competitive market. Since pure bundling is relatively effective on leveraging the monopoly power according to the previous work, the debate is often on its legal execution. However, different from the previous work, we find that the multiproduct monopoly has no incentive to engage in pure bundling (bundle the monopolized product with the product of the competitive market) when consumers’ reservation price is relatively low. But when the reservation price is relatively high, it may bundle for the purpose to foreclose the market and earns a highest monopoly profit. In Peitz (2008)’s two-dimensional Hotelling unit square model, vertical axis and horizontal axis stand for the surplus of buying product 1 and buying product 2, respectively. Therefore, consumers’ preferences depend on “product” (eq, two products should be represented in a two-dimensional Hotelling unit square). However, we build a model where consumers’ preferences depend on “firm”. We give an example to show the difference of the two preferences. Consider the case of Microsoft in Japan mentioned above. So in this case the firms are Microsoft and Ichitaro and the products are word processor and spreadsheet. Let us consider consumers’ preferences depend on “product”. Then, a consumer may prefer Microsoft’s spreadsheet but Ichitaro’s word processor. She considers a certain product is different from two firms. Comparatively, if consumers’ preferences depend on “firm”, a consumer who prefers Microsoft like all products from Microsoft. She considers a certain product is same from two firms, but the firms are different. We can see this as brand royalty. Therefore the leverage power of bundling may not work in this situation. And we build a model in a Hotelling unit interval rather than a two-dimensional model.In the previous work considering consumers’ preferences depend on “firm” (see Armstrong, M., and Vickers, J. 2010; Thanassoulis, 2007), there is always a reduced cost considered if a consumer buys all products from one single firm. The reduced cost may stand for repeated contract cost, cost of collecting information, or transportation cost. A consumer buying word processor from Ichitaro but spreadsheet from Microsoft will spend more costs than that she buys two together from Microsoft. It is easy to imagine that this so called one-stop shopping brings an advantage to the consumers purchasing products together from a single firm, thus a bundle may be more preferred under this assumption. However, we find that this depends on consumers’ reservation price. Different form Peitz (2008), we find that even under the reservation price where most consumers can buy the bundle, bundling is not preferred actually. Bundling only happens when the reservation price is high enough that the multiproduct firm can kick the competitor out of the market. If the reservation price is greater than a certain level, all consumers find that buying the bundle is profitable thus the firm is able to use bundling to foreclose the market and earn a monopoly profit. Our results are different from the existing studies.The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows. In section 2, the model is introduced. In section 3, we analyze equilibrium and results. In section 4, we present our conclusion.

2. The Model

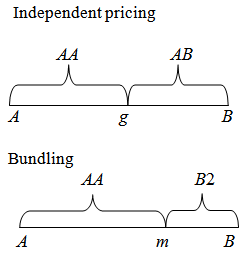

Suppose there are two products, product 1 and product 2. Product 1 is solely produced by firm A while product 2 is produced by firm A and firm B. Firm A has two strategies to select: pure bundling and independent pricing. We assume the marginal cost of either product for both firms is zero. Consumers are uniformly distributed along a Hotelling unit interval with length of 1. Firm A is located on the left corner of the interval, and firm B is located on the right corner. Consumers purchase at most one unit of each product. We assume that the markets are fully served. Under independent pricing, both the two markets should be fully covered. Therefore in the market of product 1, all consumers buy product 1 from firm A. In the market of product 2, firm A and firm B engage in full competition. Thus there are two categories of consumers, saying AA and AB. AA means consumers buying products 1 and 2 from firm A, AB means buying product 1 from firm A and product 2 from firm B. Under bundling, we can see that bundling connects the market of product 1 and the market of product 2 into one market. The competition is between the bundle and the product 2 of firm B. Unless the case where all consumers purchase the bundle (both markets are fully served), there are always some people only purchase single product 2 from firm B. Because we intend to examine the incentive for firm A to bundle under the competition with firm B, thus it is plausible to allow the fact that not all consumers can purchase product 1 under bundling. Thus there are also two categories of consumption combinations under bundling, saying AA and B2. B2 means purchasing only a single product 2 from firm B. A consumer purchasing one product will have a reservation value or reservation price of C. Therefore, a consumer will have 2C if she purchases two products. We find that the consumers’ reservation price should be greater than 2 to ensure markets to be fully served.Under independent pricing, we denote the price of product 1, product 2 from firm A, and the price of product 2 from firm B as p1A, p2A, p2BI, respectively. Under bundling, we denote the bundle price as pA, and the price of product 2 from firm B as p2BB. On the unit interval, suppose there is a consumer x (d, 0) located d away from firm A. In the case of independent pricing, consumer x purchasing AB will obtain a surplus of 2C - t × 1 - p1A - p2B. t is the strength parameter of differentiation. This consumer is d away from firm A and 1 - d away from firm B. Thus, purchasing two products from two firms induces a cost t × 1. However, if she purchases AA, she will obtain a surplus of 2C - λ × d - p1A - p2A, where t ≤λ≤ 2t, meaning she incurs a reduced cost owing to one-stop shopping. In the case of bundling, consumer x purchasing the bundle from firm A will obtain a surplus of 2C -λ× d - pA. If she buys only product 2 from firm B, she will earn a surplus of C - t × (1- d) – p2B.We denote the profit of firm A, the profit of firm B under independent pricing as πAI and πBI. And we denote the profit of firm A, the profit of firm B under bundling as πAB and πBB.

3. Equilibrium Prices and Results

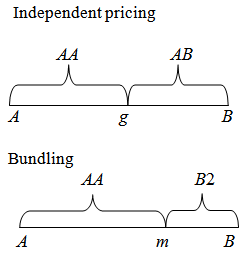

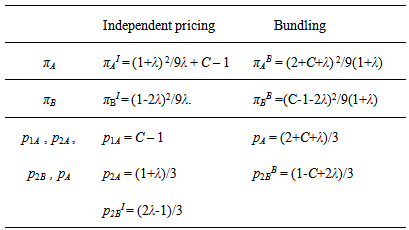

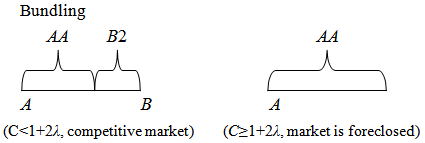

For simplicity of calculation, we set t = 1, thus 1 ≤λ≤ 2. We show the market configurations in Figure 1 (In Figure 1, we just consider the case where firm B competes with firm A).  | Figure 1. Market configurations under independent pricing and bundling |

3.1. Independent Pricing

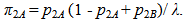

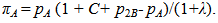

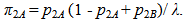

Usually because product 1 and product 2 are independent, we can put them on two unit intervals and calculate separately. However, since buying AA induces a reduced cost for one-stop shopping and this makes the purchasing decision of the two products related, thus we need to put the two products on one interval to calculate. We can calculate the critical point g to be indifferent between buying AA and AB, where 2C-p1A-p2A-λ×g=2C-p1A-p2B-1. We obtain g = (1-p2A+p2B)/λ and product 1 is not in this demand function. We can easily see that all consumers buy product 1, therefore the competition is only between A2 and B2. Then, we can calculate the profits from product 2 of the two firms, π2A and π2B (πB) as follows:  | (1) |

| (2) |

We maximize firm A’s profit with respect to p2A and firm B’s profit with respect to p2B, and we obtain p2A = (1+λ)/3, p2B I= (2λ-1)/3, π2AI = (1+λ) 2/9λ, πBI = (1-2λ)2/9λ.Then we consider the market of product 1. All consumers buy product 1. Therefore, firm A sets the highest price for product 1 to ensure that all consumers buy A1, so the consumer (1,0) located furthest from firm A will just have a zero surplus C-p1A-1=0, and then, p1A=C-1, π1AI=C-1. Therefore, the total profit of firm A is πAI= (1+λ) 2/9λ+C-1.

3.2. Bundling

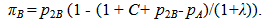

Similar to the above calculation, we can calculate the critical point m to be indifferent between buying AA and B2: 2C-pA-λ×m=C-p2B-(1-m). We obtain m=(1+C+p2B- pA)/(1+λ), then we have the profit functions as follows: | (3) |

| (4) |

We maximize firm A’s profit with respect to pA and firm B’s profit with respect to p2B, and we obtain pA = (2+C+λ)/3, p2BB = (1-C+2λ)/3, πAB = (2+C+λ) 2/9(1+λ), πBB = (C-1-2λ)2 / 9(1+λ).

3.3. Independent Pricing vs. bundling

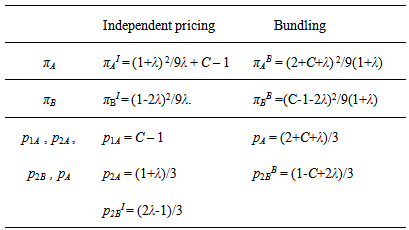

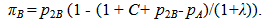

After the comparison of the equilibrium, we find that independent pricing is always the dominant strategy for firm A. firm B also gets higher profit under independent pricing. We show the equilibrium in Table 1 and the comparisons in Appendix.Table 1. Equilibrium Prices and Profits

|

| |

|

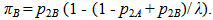

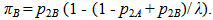

Under independent pricing, the competition is only in the market of product 2. However, under bundling, the competition is between the bundle and the single product 2 of firm B. In this situation, there are two reasons why independent pricing is preferred. First, firm A has stronger incentive to cut the price under bundling. Under independent pricing, cutting the price of product 2 will just increase the demand of product 2. And firm A monopolizes the whole market 1, thus there is no incentive to cut price of product 1. Comparatively, under bundling, cutting price of either product is in fact equal to cutting the bundle price and it will increase the demand of two products at the same time. Therefore, we can see pA <p1A + p2A. Second, under bundling, the reduced cost from one-stop shopping makes an advantage for consumers to buy the bundle, thus firm A is more competitive. Moreover, as C increases, more and more consumers prefer to buy the bundle. In order to compete with firm A’s bundle, firm B has to set a lower price for its single product 2. We can see p2BB< p2BI. Therefore, form the above two factors, it is easy to understand that the competition is fiercer under bundling and it harms both firms’ profits. In addition, under bundling, pA = (2+C+λ)/3, which increases as C increases. By contrast, p2B = (1-C+2λ)/3, which decreases as C increases. It is easy to understand why pA increases as C increases but p2B is in the opposite. As C increases, more and more consumers prefer to buy the bundle. We assume that firm B stays in the market to compete with firm A, thus p2B must be positive, eq, p2B = (1-C+2λ)/3>0 or C<1+2λ.However, we find that p2B will be zero when C=.1+2λ. This means that firm B can no longer live in the market. It will never happen under independent pricing. Thus if the reservation price C≥1+2λ, firm A has the incentive to use bundling to foreclose the market. At this time, the market configuration in Figure 1 under bundling is fully served by firm A with AA. We show this change in Figure 2.  | Figure 2. Market configurations under bundling |

Because if C≥1+2λ, both markets are monopolized by firm A thus it can earn twice monopoly profit, saying 2(C-1), only under bundling. If firm A does not bundle, firm B (or a competitor) will always exist in the market. Therefore, firm A has an incentive to bundle, thus foreclose the market to earn a highest monopoly profit when C≥1+2λ. However, firm A never wants to bundle if C<1+2λ.

4. Conclusions

This article sought to understand the incentive of bundling for a multiproduct firm which monopolizes one market but competes in another market. Under the assumption that consumers’ preference depends on “firm”, we find different results from the previous studies. Independent pricing dominates bundling if firm B exists in the market, because under bundling the competition is fiercer and it harms firms’ profits. However, firm A is able to use bundling to foreclose the market if the reservation price is relatively high. We assume that the reservation prices of the products for both firms are same, but the results under different reservation prices for two products may be different. In addition, for the complexity, we did not analyze the welfare. These could be the future topics.

Appendix

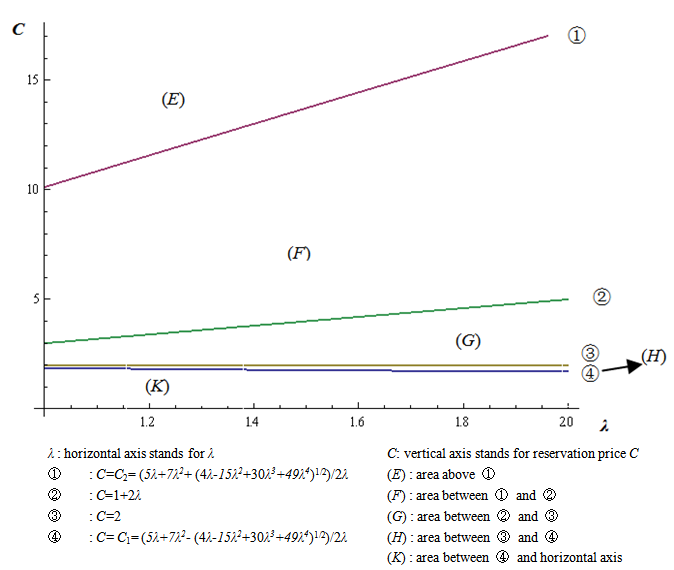

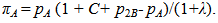

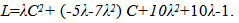

From the above analysis, we know that C must follow two restrictions: (1) C>2; (2) C<1+2λ. a. πAI vs. πABTo compare the profit of firm A under independent pricing and bundling, we examine πAB-πAI. πAB-πAI = (-1+10λ-5Cλ+C2λ+10λ2-7Cλ2)/ 9λ(1+λ). Because 9λ(1+λ) >0 always, we only see -1+10λ-5Cλ+C2λ+10λ2-7Cλ2, and we set it as function L, | (5) |

We find that (-5λ-7λ2)2-4λ(10λ2+10λ-1) is always positive when λ∊[1,2]. This means that L=0 has two solutions of C1, C2. Then we set formula L=0 and the solutions are: | (6) |

| (7) |

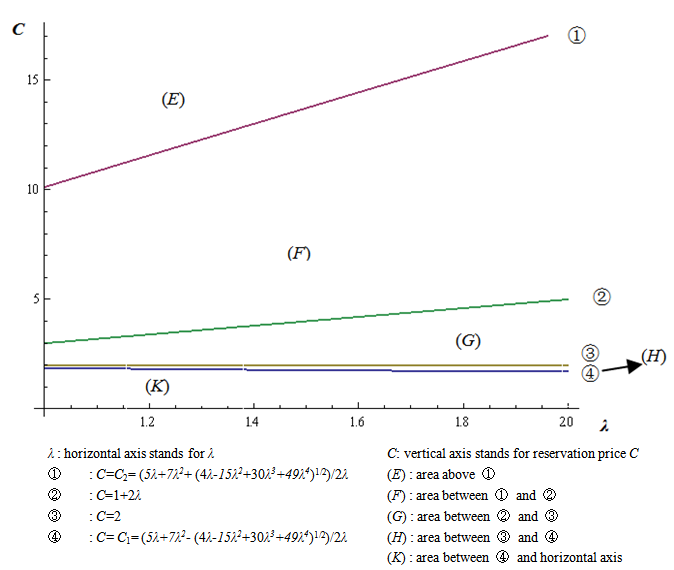

We can find C1< C2, and we show the solutions in Figure 3. Therefore,L>0, if C< C1 (area (K)) or C> C2 (area (E)). L<0, if C1<C< C2 (area (F), (G), (H)). | Figure 3. Solution for firm A |

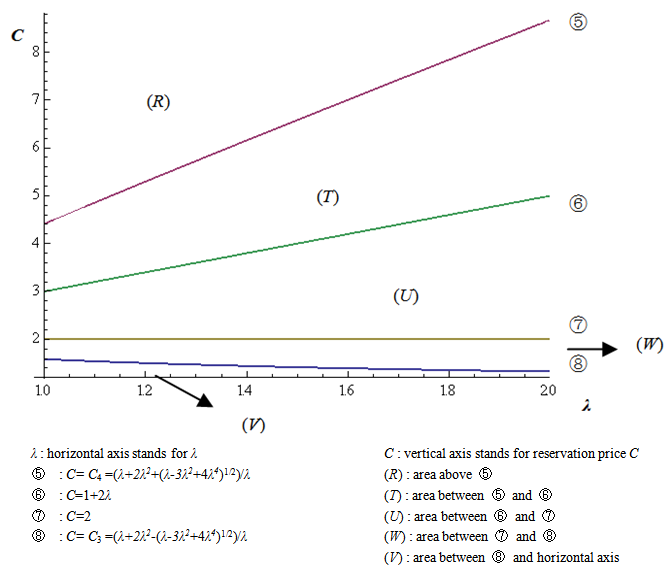

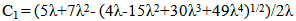

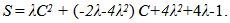

However, we have two restrictions, C<1+2λ (area (G) + (H) + (K)) and C>2 (area (G) + (F) + (E)). We find that C1<2, C2 >2, 1+2λ>2 always. Under the restrictions, we only consider area (G). We know that L<0 (eq. πAB-πAI <0) in (G) always. Therefore, independent pricing always dominates bundling.b. πBI vs. πBBπBB-πBI = (-1+4λ-2Cλ+C2λ+4λ2-4Cλ2)/ 9λ(1+λ). We set (-1+4λ-2Cλ+C2λ+4λ2-4Cλ2) as function S, then we have | (8) |

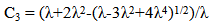

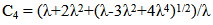

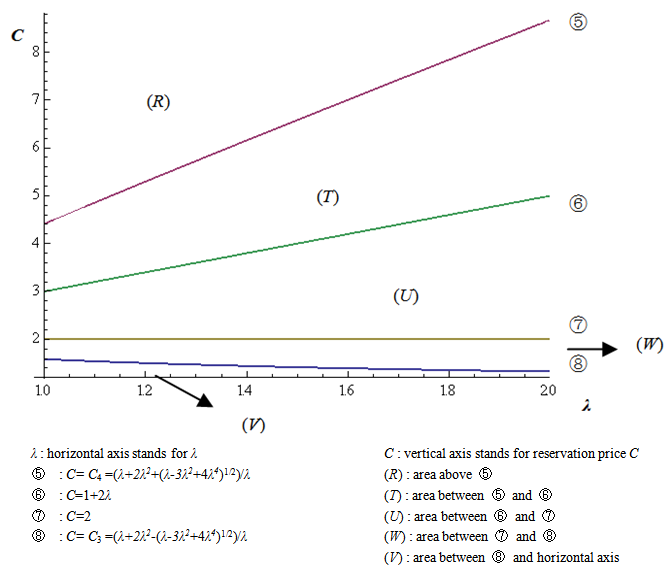

We find that (-2λ-4λ2)2-4λ(4λ2+4λ-1) is always positive when λ ∊ [1,2]. This means that S=0 has two solutions of C3, C4. Then we set formula S=0 and the solutions are: | (9) |

| (10) |

We show the solutions in Figure 4. Therefore,S>0, if C< C3 (area (V)) or C> C4 (area (R)). S <0, if C3<C< C4 (area (T), (U), (W)). | Figure 4. Solution for firm B |

Under the two restrictions of C<1+2λ (area (U) + (W) + (V)) and C>2 (area (U) + (T) + (R)), we find that only area (U) is considered. Then we have S<0 (eq, πBB-πBI <0) always. Therefore, firm B earns more profit under independent pricing. c. p1A + p2A vs. pApA – (p1A+p2A) = 2(2-C) /3. It is easy to see that 2(2-C) /3<0 if C>2. Therefore, the bundle price is always smaller than the sum of the prices under independent pricing. d. p2BI vs. p2BBp2BB- p2BI = (2-C)/3. We have (2-C) /3<0 if C>2. Thus the price of firm B’s product 2 is higher under independent pricing.

Notes

1. The reservation price (willingness to pay) is the highest price that a consumer is willing to pay. If it is high, consumers are willing to purchase more and thus more consumers can buy the bundle (two products). This may be a good condition for pure bundling. However, we find even most consumers can buy the bundle, bundling is not preferred. 2. A consumer may consider the quality of the product is different from two firms. But she does not see difference in the firm brand.3. One example is the supermarket industry. The goods sold are same for a consumer, but she prefers the supermarket located closer to her.4. Thanassoulis (2007) examined the incentive of mixed-bundling in a duopoly market. But he did not show in a graphical way as we do in this article, and the model and the topic are different.5. A consumer incurs different transportation costs for different supermarkets. However, the cost does not increase in proportion to the number of goods bought in a specific store.6. Under independent pricing, because product 1 and product 2 are independent, the competition is only in the market of product 2. Under bundling, the competition is between the bundle and the single product B2.7. Because when the market of product 1 is not fully served under independent pricing, we can easily know a consumer located at (d, 0) will buy product 1 if C - t ×d – p1A ≥0. Thus it is easy to get both the maximized price and the demand of profit 1 is C/2. When C=2, the market is fully served. If the monopoly market is fully served, all the other competitive market should be fully served. In addition, under bundling, the competition is fiercer with lower prices thus all consumers can purchase (AA or B2).8. Because td stands for consumers’ preference, thus we cannot consider as transportation fee only. If a consumer buys two products without considering one-stop shopping effect, we need consider the preferences towards two products, saying 2td. Therefore by considering one-stop shopping effect, λd is less than 2td if t ≤λ≤ 2t, representing an existence of reduced cost for one-stop shopping. 9. The reduced cost such as transportation cost or contract cost reduced from one-stop shopping always exists under firm specific preference in the previous work. 10. We want to analyze the incentive of bundling when competitor always exists. However, as C increases, the market may be foreclosed by firm A. we analyze it in the later subsection 3.4. 11. Because buying two products brings twice increased reservation value than the increased value from buying only one product as C increases, it is more profitable to buy the bundle then. 12. 2(C-1) is greater than the profit under independent pricing on our restriction that C is greater than 2.13. Here we calculate the case where firm B competes with firm A, thus we only consider C<1+2λ.14. We can consider L=aC2+bC+c. therefore, (-5λ-7λ2)2-4λ(10λ2+10λ-1)=b2-4ac.

References

| [1] | Peitz., M. (2008): “Bundling May Blockade Entry,” International Journal of Industrial Organization, 26, 41–58. |

| [2] | Nalebuff, B. (2004): “Bundling as an Entry Barrier,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 119, No. 1, 159–187. |

| [3] | Armstrong, M., and Vickers, J. (2010): “Competitive Nonlinear Pricing and Bundling,” The Review of Economic Studies, 77(1), 30–60. |

| [4] | Gans, J., and King, S. (2005): “Paying for Loyalty: Product Bundling in Oligopoly,” Journal of Industrial Economics, LIV (1), 43–62. |

| [5] | Peitz, M., and Belleflamme, P. (2010): Industrial Organization: Markets and Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

| [6] | Thanassoulis, J. (2007): “Competitive Mixed Bundling and Consumer Surplus,” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 16, 437–467. |

| [7] | Whinston, M. (1990): “Tying, Foreclosure, and Exclusion,” American Economic Review, 80(4), 837–860. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML