Adejumo Oluwabunmi Opeyemi

Institute for Entrepreneurship and Development Studies, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adejumo Oluwabunmi Opeyemi, Institute for Entrepreneurship and Development Studies, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to carry out an overview on the concept of elasticity in economics as well as to find out how well such notion can be applied to our everyday life. Besides, it is important to find out the effect a change in certain policy objective will shape or reshape on an individual, as well as an entire economy like Nigeria. Hence, the paper concentrated on the environs of the Obafemi Awolowo Univesity, Ile-Ife, as a case study. Using appropriate statistical analysis, it discovered that the Obafemi Awolowo Univeristy lecturers led an average income life, thereby confirming the developing nature of the Nigerian economy.

Keywords:

Change, Income, Demand, Elasticity

Cite this paper: Adejumo Oluwabunmi Opeyemi, The Theory and Applications of Elasticity: A Study on Consumers in Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 313-321. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20130306.10.

1. Introduction

The concept of elasticity is an imperative functional tool for economist, policy makers and businessmen and businesswomen, therefore, its role in decision making and forecasting issues cannot be overlooked. The concept of elasticity which lies within the neoclassical economic theory can be used to determine the magnitude of a change in certain variable in relation to other critical determining variable. In fact, from policy perspectives, the notion of elasticity can be used to find out the effect certain changes in government and institutional will have policies on an economy. While such changes could either be measured at a point in time or over a period of time, the use of elasticity can equally assist in determining the direction of relationship that changes in policies will have on an economy. This will help individuals and decision makers to be persistent in their actions or make amends where necessary[1]. Empiricists, that have particularly worked in this regard of explaining certain economic phenomenon via the elasticity principle, especially making use of simple linear regression and least squares estimates, have found the concept of elasticity useful in explaining most analysis within their domain. But, its adequacy in explaining the behavior economic phenomenon remains suspicious. Therefore, an appraisal of the theoretical concept of elasticity will be spelt out, while the areas where elasticity can be applied will be equally examined. Sequel to this, an empirical analysis on the subject matter will be examined using some lecturers within the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria, as a case study. Finally, the shortcomings of the elasticity concept will be treated just before concluding the study.

2. Theory of Elasticity

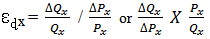

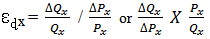

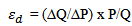

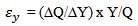

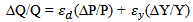

Elasticity, as the word implies, is used to determine the response of a variable to a change in some other variables,[3]. Besides, the word elasticity can be used in a general sense. Generally, an elastic variable is one which responds a lot to small changes in other parameters. Similarly, an inelastic variable describes one which does not change much in response to changes in other parameters. But in a specific sense, elasticity could be narrowed down to different disciplines such as physics, economics, and humanities, to mention a few,[8]. With particular emphasis on its use in economics, one could determine the degree of response of a variable such as demand to some other variables like price, income, prices of other products which could either be a substitute or a complement. Therefore, the response variable (demand) which is being analyzed in relation to other exogenous variable will then coin the title of elasticity being measured. For instance, if individual demand (or supply) is being analyzed, given changes in price of a particular commodity, we have price elasticity of demand (or supply); likewise, if we analyze how individual demand (or supply) behaves given changes in his income, we would have income elasticity of demand (or supply). Hence, the elasticity could be used to measure the degree of responsiveness to varying factors that could shape demand (or supply) as the case may be. The formula for calculating a commodity (say x) will then be  | (1.1) |

Where  = the elasticity of demand for good x,

= the elasticity of demand for good x,  = Price of demand for good x,

= Price of demand for good x, = quantity of demand for good x,

= quantity of demand for good x, = is used to denote change or difference.But, if elasticity is measured in percentage terms, then we can refer to elasticity of demand as a percentage change in the quantity demanded of a product, given certain changes in some other factors that shape demand such as price. This can also be denoted as

= is used to denote change or difference.But, if elasticity is measured in percentage terms, then we can refer to elasticity of demand as a percentage change in the quantity demanded of a product, given certain changes in some other factors that shape demand such as price. This can also be denoted as  | (1.2) |

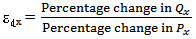

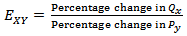

The concept  can simply be changed to ɛSx in order to explain the elasticity of supply and we would mean the same thing. The difference only occurs while interpreting the results obtained[9].Applying either of the point measurement of elasticity above, a unique solution could be arrived at, which is denoted as the elasticity coefficient. This unique solution could take five different forms of elasticity cases.Perfectly or Infinitely Elastic Case: if the elasticity coefficient is infinity, i.e. ∞. This would imply that a 1% increase in price will lead to a situation where nothing is demanded. While in the case of supply, it implies the supplier will be willing to supply as much as possible.Fairly Elastic Case: this implies the 1% increase in price will lead to more than 1% decrease in quantity demanded. While in the case of supply, a 1% increase in price will lead to more than 1% increase in quantity supplied.Perfectly or Zero Inelastic Case: this is when the elasticity co-efficient is zero. This implies that changes in price have no effect on quantity demanded and supplied.Fairly Inelastic Case: this is when the elasticity co-efficient is greater than positive but less than one. This implies that a given change in price will lead to less than a proportionate change in quantity demanded or supplied.Unitary Inelastic Case: if elasticity co-efficient is one (unity), it means that a given percentage change in price gives rise to the same percentage change in quantity demanded or supplied.But, it must be noted that elasticity is dimensionless, that is it has no specific unit of measurement, and can only be interpreted in terms of percentage and as a result, it must be measured in percentage terms. Besides, the advantage of using percentages is that it affords a common basis for comparison. It must be equally noted that for cases of price elasticity of demand, the solutions must be preceded by a minus. This is because it follows certain logical consequences of arithmetic operation, as well as a theoretic economic rationale; the inverse relationship between price and demand. Although, this sign may be ignored in some cases, where the analytical results states otherwise, but the interpretation of such cases should be clearly spelt out. Meanwhile, for the price elasticity of supply, the use of a plus or positive sign preceding the coefficient is required. This is because of the direct relationship between price and supply; but, where the analytical results states otherwise also, the interpretation of result should justify such position[4].Finally on the issue of price elasticity, there is also the concept of cross-price elasticity of demand for say good X and Y(EXY), which measures the percentage change in the quantity of good X as a result of a change in the price of good Y. Operationally, it is given as:

can simply be changed to ɛSx in order to explain the elasticity of supply and we would mean the same thing. The difference only occurs while interpreting the results obtained[9].Applying either of the point measurement of elasticity above, a unique solution could be arrived at, which is denoted as the elasticity coefficient. This unique solution could take five different forms of elasticity cases.Perfectly or Infinitely Elastic Case: if the elasticity coefficient is infinity, i.e. ∞. This would imply that a 1% increase in price will lead to a situation where nothing is demanded. While in the case of supply, it implies the supplier will be willing to supply as much as possible.Fairly Elastic Case: this implies the 1% increase in price will lead to more than 1% decrease in quantity demanded. While in the case of supply, a 1% increase in price will lead to more than 1% increase in quantity supplied.Perfectly or Zero Inelastic Case: this is when the elasticity co-efficient is zero. This implies that changes in price have no effect on quantity demanded and supplied.Fairly Inelastic Case: this is when the elasticity co-efficient is greater than positive but less than one. This implies that a given change in price will lead to less than a proportionate change in quantity demanded or supplied.Unitary Inelastic Case: if elasticity co-efficient is one (unity), it means that a given percentage change in price gives rise to the same percentage change in quantity demanded or supplied.But, it must be noted that elasticity is dimensionless, that is it has no specific unit of measurement, and can only be interpreted in terms of percentage and as a result, it must be measured in percentage terms. Besides, the advantage of using percentages is that it affords a common basis for comparison. It must be equally noted that for cases of price elasticity of demand, the solutions must be preceded by a minus. This is because it follows certain logical consequences of arithmetic operation, as well as a theoretic economic rationale; the inverse relationship between price and demand. Although, this sign may be ignored in some cases, where the analytical results states otherwise, but the interpretation of such cases should be clearly spelt out. Meanwhile, for the price elasticity of supply, the use of a plus or positive sign preceding the coefficient is required. This is because of the direct relationship between price and supply; but, where the analytical results states otherwise also, the interpretation of result should justify such position[4].Finally on the issue of price elasticity, there is also the concept of cross-price elasticity of demand for say good X and Y(EXY), which measures the percentage change in the quantity of good X as a result of a change in the price of good Y. Operationally, it is given as: | (1.3) |

Or | (1.4) |

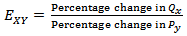

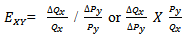

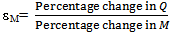

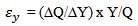

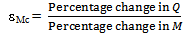

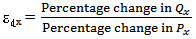

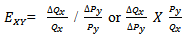

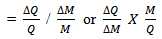

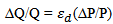

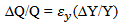

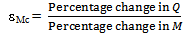

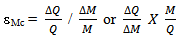

When the cross price elasticity co-efficient is negative, it suggests that the two goods are complements; if positive, it suggests that they are substituted; but if it is zero, it means they are independent and not related in demand at all. Cross elasticity of demand for firms, are sometimes referred to as conjectural variation. This is because it is a measure of the interdependence between firms. It captures the extent to which one firm reacts to changes in strategic variables (price, quantity, location, advertising, etc.) made by other firms,[2].Digressing a little from the price elasticity of demand and supply, it is also important to find out the effect a change in the income of a consumer can have on the demand for certain products- which is usually referred to as income elasticity of demand. More formally, it can be calculated as: | (1.5) |

or | (1.6) |

Where  = the elasticity of income, Q = quantity demanded,M = money income,

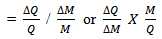

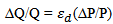

= the elasticity of income, Q = quantity demanded,M = money income, = is used to denote change or difference.The concept of income elasticity is important in many respects. First, it shows the degree of responsiveness in the demand for any good to changes in income. Therefore, it means a 1% change in the income of consumer, ceteris paribus, will lead the consumer to increase the demand for a particular commodity. Besides, the unique solution arrived at in the course of calculations could take four different forms:Normal Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is greater than zero (that is ɛM > 0), it implies that the good is normal or superior. This means that the higher the income, the same or little more quantity of a particular product will be preferred. For instance, basic needs such as food, clothing, shelter, health, clothings, e.t.cInferior Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is less than zero (that is ɛM < 0), it implies that the good is inferior. This means that the higher the income, the lesser quantity of a particular product will be bought. For instance, second-hand productsLuxury Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is greater than one (that is ɛM > 1), it implies that the good is luxury one. This means that the higher the income, the higher quantity of such a particular product will be bought. For example cars, holiday travels, etcNecessary Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is less than one (that is ɛM < 1), it implies that the good is necessary good or above normal or more than superior good. This means that whatever the state of your income, they are class of goods that you just cannot do without them. Examples include salt, clothings, transport fares, e.t.c,[10].In real world cases, a good analysis of elasticity carried out could guide investors and business persons on which areas to invest or divest. This is because, areas that have income-backed demand are very vital to the success of any venture. Thus, if a good is found to be strongly income elastic at any given income price, demand for it will shift outwards as income increases, thereby, influencing sales, revenue and profit.Aside the regular elasticity measurements, there is also the elasticity of intertemporal substitution- where it is possible to consider the combined effects of two or more determinant of demand. The steps are as follows: Step 1: Given the Price Elasticity of Demand Equation(εd), then,

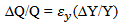

= is used to denote change or difference.The concept of income elasticity is important in many respects. First, it shows the degree of responsiveness in the demand for any good to changes in income. Therefore, it means a 1% change in the income of consumer, ceteris paribus, will lead the consumer to increase the demand for a particular commodity. Besides, the unique solution arrived at in the course of calculations could take four different forms:Normal Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is greater than zero (that is ɛM > 0), it implies that the good is normal or superior. This means that the higher the income, the same or little more quantity of a particular product will be preferred. For instance, basic needs such as food, clothing, shelter, health, clothings, e.t.cInferior Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is less than zero (that is ɛM < 0), it implies that the good is inferior. This means that the higher the income, the lesser quantity of a particular product will be bought. For instance, second-hand productsLuxury Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is greater than one (that is ɛM > 1), it implies that the good is luxury one. This means that the higher the income, the higher quantity of such a particular product will be bought. For example cars, holiday travels, etcNecessary Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is less than one (that is ɛM < 1), it implies that the good is necessary good or above normal or more than superior good. This means that whatever the state of your income, they are class of goods that you just cannot do without them. Examples include salt, clothings, transport fares, e.t.c,[10].In real world cases, a good analysis of elasticity carried out could guide investors and business persons on which areas to invest or divest. This is because, areas that have income-backed demand are very vital to the success of any venture. Thus, if a good is found to be strongly income elastic at any given income price, demand for it will shift outwards as income increases, thereby, influencing sales, revenue and profit.Aside the regular elasticity measurements, there is also the elasticity of intertemporal substitution- where it is possible to consider the combined effects of two or more determinant of demand. The steps are as follows: Step 1: Given the Price Elasticity of Demand Equation(εd), then, | (1.7) |

Step 2: Equation (2.7) above can be converted to the predictive equation:  | (1.8) |

Step 3: Given the Income Elasticity of Demand Equation(εd), then, | (1.9) |

Step 2: Equation (2.9) above can be converted to the predictive equation:  | (1.10) |

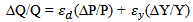

Now, if one desires to obtain the combined effect of changes in two or more determinants of demand you simply add the separate effects (for instance the Price Elasticity of Demand (εd) and Income Elasticity of Demand (εy):  | (1.11) |

It must be recalled that you are still only considering the effect in demand of a change in two of the variables. All other variables must be held constant. Note also that graphically this problem would involve a shift of the curve and a movement along the shifted curve,[7].

3. Applications of Elasticity

Elasticity of demand and supply can be useful in a variety of cases. For instance, it is useful in understanding the incidence of indirect taxation, marginal concepts as they relate to the theory of the firm, the distribution of wealth and different types of goods as they relate to the theory of consumer choice,[11]. Elasticity is also crucially important in any discussion of welfare distribution, in particular consumer surplus, producer surplus, or government surplus. While in empirical work an elasticity is the estimated coefficient in a linear regression equation where both the dependent variable and the independent variable are in natural logs. Elasticity is a popular tool among empiricists because it is independent of units and thus simplifies data analysis[5].Specifically, a relationship between demand and total sales can be identified. For instance, if total sales are the amount of money obtained from the sales of a given number of products, then the knowledge of elasticity can assist in predicting the behavior of total sales, if a change in price occurs. Let us assume a fairly elastic demand situation for a product, if there is an increase in price, an inverse relationship is expected to occur between demand and total sales. But if demand is fairly inelastic, a positive relationship will be expected to occur between demand and total sales, which will be as a result of price reduction. Likewise, if there is an increase or decrease in the price of a commodity, and demand is unitary elastic, the relationship between demand and total sales will be constant. Furthermore, the notion of elasticity is applicable in the attitude of middlemen in business. Middlemen serve as a vital link in the chain of distribution of commodities from producers to consumers. Therefore, they perform an economic function for which returns are expected. But, hoarding of commodities is seen as a rational strategy for maximizing their returns. Hoarding seems to be achievable if supply is inelastic (inelastic here means that supply remain static or fairly static); therefore, the more inelastic the supply of the product, the higher the price of the product as demand shifts. Thus, if demand keeps changing, and supply remains unchanged, scarcity is bound to occur. Take the fuel supply problem in Nigeria as an example, once scarcity occurs, prices will shoot up and consumers are ready to pay any amount for the little quantity of the fuel available. But, if supply is elastic, it means whatever the quantity supplied, the price will not change. This is because the product will be available for consumers everywhere, thus the consumer is favored and hoarding will be impossible,[12].The concept of elasticity is equally useful in explaining tax incidence. When a tax is imposed on a commodity, the onus lies on the producer to pay the tax to the government. The incidence of such a tax between the producer and consumers, now depend on the elasticity of demand for such a product. Hence, the relative burden of such a tax, which is a cost, will fall more on the group having lower elasticity between the seller and the buyer,[13]. For instance, if a producer decides to reduce his supply of a product, say rice, and the price of the product increases, if the demand for the product is inelastic, the producer can successfully pass the bulk of the tax incidence to the consumer; but if the price falls and the demand for the product remains inelastic, the producer will bear more of the tax burden. The time span of a product could affect the elasticity of such a product. Usually, the longer the time span of a product, the more elastic the demand for the product. Although, in the short-run, the demand for the product may be elastic, but as long as the product remains relevant, important and useful, it may become inelastic. This can only be avoided, where adequate substitutable commodity are made available. Still on the example of crude oil in Nigeria, initially, when few persons were using cars, it was easy to overlook the hike in fuel prices and prefers to pay more in terms of transport fares; but these days, the moment there is crude oil scarcity, business, trade and production activities are severely affected. Hence, the inability to adequately substitute crude oil as a source of in Nigeria makes the product inelastic. But on the international scene, numerous alternatives to fuel have been discovered such as bio-fuel, solar energy, coal e.t.c. and as a result, the elasticity of demand for petrol-fuel energy is increasing[14].The essentiality or desire of a product to the needs of a consumer to his income can affect elasticity of demand for such a product. For instance, the purchase of food is essential and desirous, and as such the demand for such product will be inelastic; thus if the prices of food items goes up, people will still prefer to reduce consumption of other commodities and but more of food, since it is basic to sustaining life. In addition, if the prices of certain products (cheap dresses or water bill, electricity bill) are negligible in relation to one’s income, one will be inelastic. But, if the price of a given item is substantial in relation to the consumer’s income, demand for it tends to be elastic; this is because it takes a larger portion of the total income. For instance, if the purchase of a house to a low or middle income earner is substantial to an individual income, the person will be more elastic; therefore, the individual can postpone the purchase of the house till he gets to a higher income level, or decide to save in bits or borrow more to make-up the purchase[15].Whenever regression analysis is applied to a log-linear equation, the result of the regression analysis is expected to be interpreted using elasticity. The ease of using elasticity enables non-economist or non-statistician to understand the interpretation of such analysis. This is because the analysis will explained using percentages which is appreciable to most users of analytical results.In addition, the use of elasticity in explaining regression analysis enables its application to a wide range of data, whether micro or macro variable cases. Hence, no matter how large a variable is, it could be manipulated to carry out regression analysis, transformed to logarithmic equations and then interpreted in terms of elasticity.

4. Empircal Analysis of Elasticity

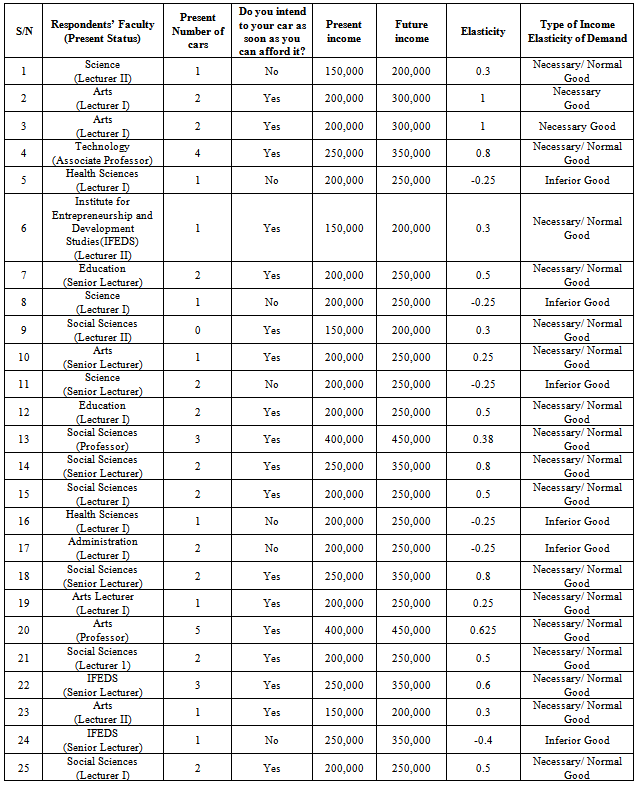

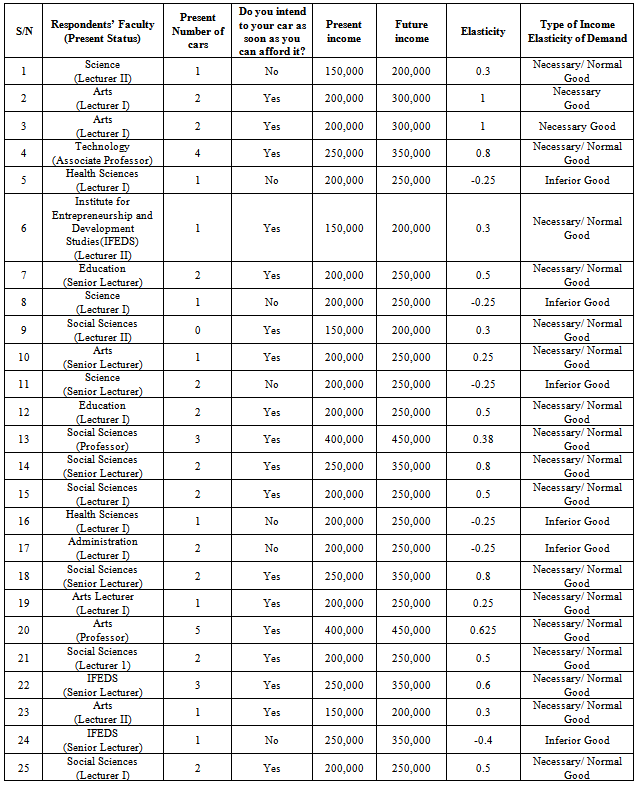

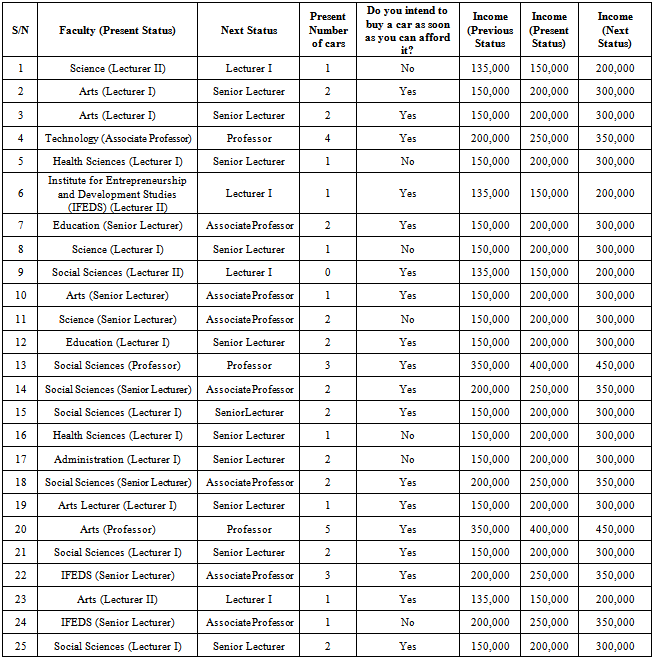

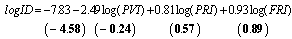

Empirically, the notion of elasticity can be applied to both micro-economic variables such as individual demand for certain products, thereby, measuring the behavior of such a consumer at a point in time. Likewise, elasticity, using econometric analysis can be applied to macro variables thereby, using it to explain certain economic variable within a country such as the effect of government spending in different sectors (health, education, agriculture, industry, e.t.c.) on economic growth. In a micro study, the income elasticity of the demand for cars amongst different cadres of lecturers of the Obafemi Awolowo University, Osun state, Ile-Ife, Nigeria was examined. During a cross-section of the Academic Staff University Union (ASUU) meeting, questionnaires were administered randomly to twenty-five lecturers to find out if their present income status has any relationship on their demand for cars. Besides, it was also important to know whether if there is a change in income status, there will be an increase in the demand for cars amongst the lecturers of the Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), Ile-Ife, (see Apendix 1 for questionnaire). Furthermore, the analysis will enable an effective determination whether the cars are necessities, luxuries, inferior or a normal good amongst the lecturers within the University community. If a linear relationship is expected between income changes and the demand for cars, This section will be grouped into two; the point income elasticity estimates of each of the sampled lecturer will be determined and put in a table, while the regression estimate to determine the overall elasticity of all the sampled lecturers will be carried out.

4.1. Point Elasticity Measurement for Income Elasticity of Demand for Cars amongst OAU, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria Lecturers

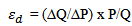

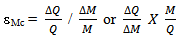

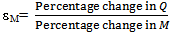

The point elasticity can be used to determine the degree of responsiveness of a consumer demand to a particular product. With regard to this study, it is important to find out if there is a shift of a lecturer in OAU from one cadre to another, what effect it will have on his demand for cars on the average at point in time. Specifically, the present number of cars owned by each lecturers will be used to capture the demand for cars, while the average income earned per cadre will be drawn from the Federal government salary scheme for Academic Staff Union of Universities; The change in income status per lecturer will be determined through the next average income level for the next status. The formulae applied to generate the elasticity is  | (2.1) |

or | (2.2) |

Where  represent money income,

represent money income,  represents quantity of cars demanded,

represents quantity of cars demanded,  represent elasticity of money, while

represent elasticity of money, while  is used to denote change or difference.

is used to denote change or difference.Table 1. Point Measurement of Income elasticity of the demand of the demand for cars amongst OAU Lecturers

|

| |

|

It is to be noted that, for the question “do you intend to buy an additional car as soon as you can afford it”, assumes that a movement from the present income level to the next level should buy at least one car in addition to the one he has presently; therefore, those who say ‘yes’ agree with the question, while those who say ‘no’ are assumed to buy no car.From table 1, 24% of the sampled lecturers see the commodity car as an inferior good. This implies that presently, as the income level of these lecturers’ changes from the present level to the next cadre in the hierarchy of the lecturing profession, there will be no new purchase of cars by these set of lecturers. This could be because there are more pressing needs (such as house rent, children school fees, and feeding, clothing, e.t.c.) than the purchase of a new car that needs urgent attention. Besides, it could be that the present salary of the lecturer is not just sufficient for the purchase of a car or the lecturers don’t just fancy the need for changing their cars moment. But the income elasticity of the demand for cars amongst the remaining lecturers which are about 76%, see the need and use for car as a normal or necessary commodity. This means that whatever the state of your income, cars are a class of good that you just cannot do without especially for transportation. In addition, cars could be viewed as a normal good where if the income of a lecturer changes, the same or little more quantity of a particular product will be preferred.

4.2. Regression Analysis of the Income Elasticity of Demand for Cars amongst OAU, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria Lecturers

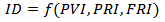

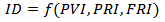

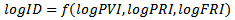

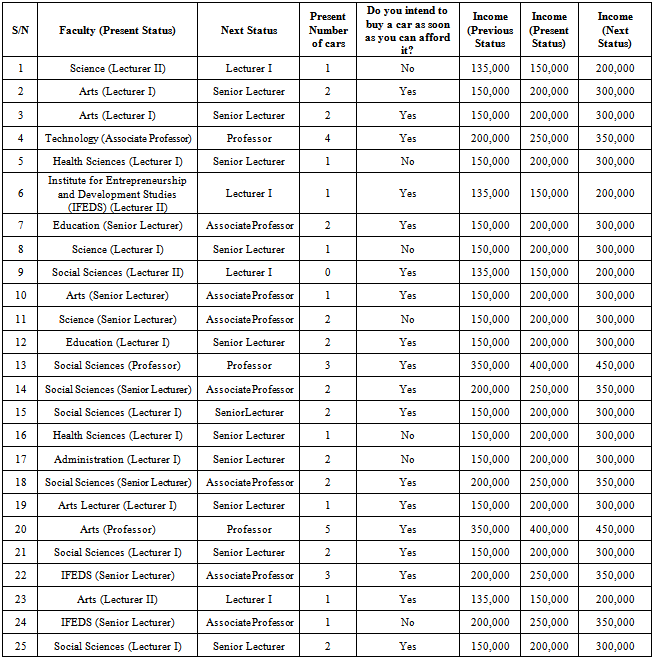

In a specific linear functional relationship, the relationship between income groups or levels and the demand for cars can be specified as seen in equation (3.1): | (3.1) |

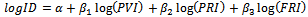

Where ID = Income demandPVI = previous incomePRI = present incomeFRI= Future IncomeIf all variables transformed to their natural logs and a linear relationship assumed to exist between income and demand for cars in OAU, equation I can be rewritten as: | (3.2) |

With equation (2) above, any regression analysis carried out, will be interpreted in terms of elasticity. Then, we can rewrite the equation (3.2) above in a more explicit equation where constants and coefficients are introduced: | (3.3) |

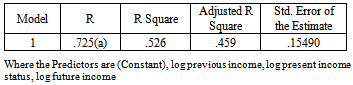

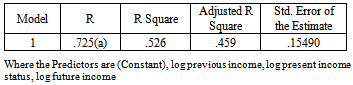

Where  Thus, the regression analysis was carried out on the qualitative data obtained to show the direction and magnitude of causation amongst the selected variables; specifically, old, present and future incomes of the lecturers were regressed on the present number of cars, (see Appendix 2 for respondents’ information) and the following results were discovered:From table 2, it can be deduced from the correlation (R = 0.725) that the relationship between income and the demand for cars among OAU is positive and high at 72.5%. Besides, the proportion of income received that explains the demand for cars by the lecturers in OAU is about 52% (as depicted by R square=0.526) and with some adjustments in the R squared, the proportion of explanation is reduced to 45.9% (as shown by Adjusted R Squared).

Thus, the regression analysis was carried out on the qualitative data obtained to show the direction and magnitude of causation amongst the selected variables; specifically, old, present and future incomes of the lecturers were regressed on the present number of cars, (see Appendix 2 for respondents’ information) and the following results were discovered:From table 2, it can be deduced from the correlation (R = 0.725) that the relationship between income and the demand for cars among OAU is positive and high at 72.5%. Besides, the proportion of income received that explains the demand for cars by the lecturers in OAU is about 52% (as depicted by R square=0.526) and with some adjustments in the R squared, the proportion of explanation is reduced to 45.9% (as shown by Adjusted R Squared). Table 2. Model Summary

|

| |

|

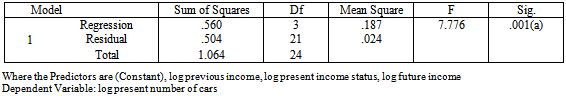

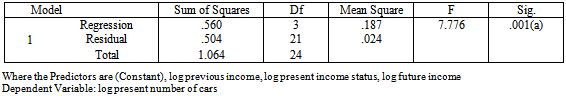

A cursory look at the analysis of variance in table 3, it can be shown that the overall significance of the variables (log present number of cars, log previous income, log present income status, log future income) that have been used is 7.8% at 1% level of significance. This implies that the with 99% level of confidence all the variables used are important for drawing inferences are significant.Table 3. (Analysis of Variance Table (ANOVA))

|

| |

|

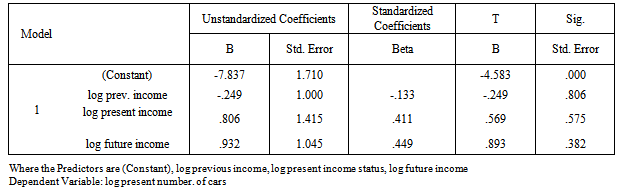

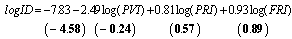

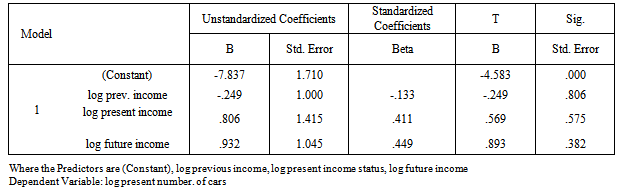

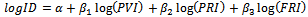

Table 4 shows the regression result of the estimates carried out, and this can be re-written as in equation (4.3). Thus, giving the result of the estimate, we have: | (3.4) |

The regression result in equation (3.4) above is similar to the point estimates generated in table 1 above. Specifically, the regression result showed that within the previous income earned by OAU lecturers or when lecturers are in a lower income group, a 1% increase in their income will reduce the demand for cars insignificantly, by 2.4%; which, according to theoretical expectation is less than zero. Therefore the implication is that in a situation where the elasticity of income is less than zero (that is ɛM < 0), it implies that the car as a commodity, is inferior to OAU lecturers at a lower income level or in a lower income group. Therefore, it can be inferred that the higher the income, the lesser quantity of a particular product will be bought. But, within the sphere of a significantly higher income level, an increase in income (as depicted by the present level of income) by 1%, will lead to an insignificant increase in the demand for cars amongst OAU lecturers by 0.81%. In a situation where the elasticity of income is greater than zero (that is ɛM > 0), it implies that the commodity, car, is normal or superior good to OAU lecturers. This means that the higher the income, the same or little more quantity of a particular product will be preferred. In addition, the commodity car can be said to be a necessary good because where the elasticity of income is less than one (that is ɛM < 1), it implies that the good is necessary good or above normal or more than superior good. This means that whatever the state of your income, they are class of goods that you just cannot do without them.It is discovered that as the lecturers move from their present income status to a higher income group (as depicted by future income), the degree of responsiveness to a 1% increase in the demand for cars may increase insignificantly by 0.93%. This, still goes to re-affirm that the commodity car on the average amongst OAU lecturers, given their income earned, remains a normal and a necessary commodity. In a literary sense, it means that as lecturers move up in their cadres, the need for cars becomes more important to them; as well as a commodity they cannot do without. Besides, at lower income levels, some lecturers may not desire cars so much either because they cannot afford it or because they have other pressing needs other than cars, which may be competing for the little money they earn.Table 4. Table of Coefficients

|

| |

|

5. Criticisms of Elasticity

The concept of elasticity, no doubt, can be applied to a wide range of cases and products. This especially is applicable in explaining demand and supply behavior, variables that shape macroeconomic behavior as well as forecasting. But, in a situation where previous information or histories of innovations are not available, the concept of elasticity cannot be useful. This is because it looks at history of changes to make its predictions; thus where this history are unavailable, there can be no measurement of change.Besides, the notion of elasticity can only be applied to naturally logged variables. For instance, where econometric analysis such regression or correlation are carried out, they must be interpreted to make inferences. Therefore, when variables are logged, the use of percentages in explaining the phenomenon in question becomes easy and possible to understand. But where variables remain in their ordinary form, they may have to be explained in other forms, such as units. Thereby, rendering the concept of elasticity inapplicableFurthermore, the elasticity concept is basically useful for linear econometric models. Where a simple linear relationship between two phenomena is carried out, the concept of elasticity is easily applicable to logged variables. But in a non-linear relationship, it may require finding a way of line arising such variables, before any inference in terms of elasticity can be made, if not, elasticity is inapplicable.

6. Conclusions

The analysis carried out so far has proved that the concept of elasticity is an imperative phenomenon for explaining economic behavior. Besides, the fact that elasticity could be applied to both micro and macro issues, makes it appealing and universally acceptable to researchers and policy makers.A the micro level, its specific application to the income elasticity of demand for cars amongst OAU, Ile-Ife lecturers revealed that given the income group the lecturers find themselves, cars remain a good of necessity on the average. And as a result, any change in income level in form of promotion, as long as the lecturers remain within the university system, the tendency of cars becoming luxury goods will be averse. Therefore, Cars can only become a luxurious commodity to these lecturers if their net pay changes significantly or a total change in the present employment by the lecturer to a highly paid or better employment by the lecturers. At the macro level, this obviously has implications on the level of development of Nigeria; basically, it points to the fact that the Nigerian economy still hovers around the subsistence level.Despite the observed short-comings of elasticity in the area of its inapplicability where non historical, non-linear and non-logged variables are unavailable, the use of elasticity remains a vital tool for basis for comparison, analysis, drawing inferences and decision making.

Appendix 1: Prototype of Questionnaire Administered to the Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), Ile-Ife, Osun State

A Questionnaire Designed to Assess the Elasticity of OAU Lecturers on the Demand for CarsGood day Sir/Ma,In an attempt to use OAU, Ile-Ife, Osun State Nigeria as a case study, I request an instance to elicit some information about the consumer behavior on the demand for cars.Kindly fill the questionnaire belowThank you Sir/Ma.Faculty…………………………………………………Department…………………………………………….Present Designation……………………………………Previous Designation………………………………….Present Number of cars………………………………..Type of car(s).....………………………………………What car do you hope to buy next as you advance in career……………………………………………………..

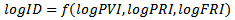

Appendix 2: Table of Response received from Administered Questionnaire

References

| [1] | Akrani Gaurav (2009). “Demand in Economics-Law of Demand- Elasticity of Demand”. Kalyan City Life. |

| [2] | Case, K; Fair, R (1999). Principles of Economics (5th ed.). |

| [3] | Collins (2003). Microeconomics. Pearson Publishing, England. |

| [4] | Fibich Gadi, Arieh Gavious, Oded Lowengart (2005). “ Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. Volume 33, No. 1, pages 66-78. |

| [5] | Gillette, David and Robert delMas (1992). "Psycho-Economics: Studies in Decision Making." Classroom Expernomics,1(2), Fall 1992, pp. 5-6 in http://www.metalproject.co.uk/METAL/Resources/Question_bank/Economics%20applications/index.html. |

| [6] | Hoffman (1998). Microeconomics with Calculus (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. |

| [7] | Landers Jim, (February 2008). “What’s the potential impact of casino tax increases on wagering handle: estimates of the price elasticity of demand for casino gaming.” Economics Bulletin, Economics Bulletin, Vol. 8, No. 6 pp. 1-15 |

| [8] | Fernie O. M. (2011). “Applications of Elasticity”. Wow Economics, |

| [9] | www.tutors2u.com © 2011 |

| [10] | Liberman Marc and Hall Robert, (2008). “Principles and Applications of Microeconomics”. Thomas South- Western, ISBN:13:978-0-3246451964- International Student Edition. |

| [11] | Economics Exposed. “Economics Problems and Solutions” economicsexposed.com/importance-of-elasticity. |

| [12] | Gruber Jon and Emmanuel Saez , (2002). “The Elasticity of Taxable Income: Evidence and Implications”. Journal of Public Economics 84, (2001), 1-32, Elsevier. |

| [13] | Gruber, J., Saez, E., 2000. The Elasticity of Taxable Income: Evidence and Implications., NBER, Working Paper No. 7512. |

| [14] | Umo Umo (1999). The Applications of Microeconomics in Nigeria, “Johnson Publishers”. |

| [15] | Umo Joe Umo (2007) "Economics An African Perspective" Published by Millennium Text Publishers Limited; ISBN 978-083-131-8 |

= the elasticity of demand for good x,

= the elasticity of demand for good x,  = Price of demand for good x,

= Price of demand for good x, = quantity of demand for good x,

= quantity of demand for good x, = is used to denote change or difference.But, if elasticity is measured in percentage terms, then we can refer to elasticity of demand as a percentage change in the quantity demanded of a product, given certain changes in some other factors that shape demand such as price. This can also be denoted as

= is used to denote change or difference.But, if elasticity is measured in percentage terms, then we can refer to elasticity of demand as a percentage change in the quantity demanded of a product, given certain changes in some other factors that shape demand such as price. This can also be denoted as

can simply be changed to ɛSx in order to explain the elasticity of supply and we would mean the same thing. The difference only occurs while interpreting the results obtained[9].Applying either of the point measurement of elasticity above, a unique solution could be arrived at, which is denoted as the elasticity coefficient. This unique solution could take five different forms of elasticity cases.Perfectly or Infinitely Elastic Case: if the elasticity coefficient is infinity, i.e. ∞. This would imply that a 1% increase in price will lead to a situation where nothing is demanded. While in the case of supply, it implies the supplier will be willing to supply as much as possible.Fairly Elastic Case: this implies the 1% increase in price will lead to more than 1% decrease in quantity demanded. While in the case of supply, a 1% increase in price will lead to more than 1% increase in quantity supplied.Perfectly or Zero Inelastic Case: this is when the elasticity co-efficient is zero. This implies that changes in price have no effect on quantity demanded and supplied.Fairly Inelastic Case: this is when the elasticity co-efficient is greater than positive but less than one. This implies that a given change in price will lead to less than a proportionate change in quantity demanded or supplied.Unitary Inelastic Case: if elasticity co-efficient is one (unity), it means that a given percentage change in price gives rise to the same percentage change in quantity demanded or supplied.But, it must be noted that elasticity is dimensionless, that is it has no specific unit of measurement, and can only be interpreted in terms of percentage and as a result, it must be measured in percentage terms. Besides, the advantage of using percentages is that it affords a common basis for comparison. It must be equally noted that for cases of price elasticity of demand, the solutions must be preceded by a minus. This is because it follows certain logical consequences of arithmetic operation, as well as a theoretic economic rationale; the inverse relationship between price and demand. Although, this sign may be ignored in some cases, where the analytical results states otherwise, but the interpretation of such cases should be clearly spelt out. Meanwhile, for the price elasticity of supply, the use of a plus or positive sign preceding the coefficient is required. This is because of the direct relationship between price and supply; but, where the analytical results states otherwise also, the interpretation of result should justify such position[4].Finally on the issue of price elasticity, there is also the concept of cross-price elasticity of demand for say good X and Y(EXY), which measures the percentage change in the quantity of good X as a result of a change in the price of good Y. Operationally, it is given as:

can simply be changed to ɛSx in order to explain the elasticity of supply and we would mean the same thing. The difference only occurs while interpreting the results obtained[9].Applying either of the point measurement of elasticity above, a unique solution could be arrived at, which is denoted as the elasticity coefficient. This unique solution could take five different forms of elasticity cases.Perfectly or Infinitely Elastic Case: if the elasticity coefficient is infinity, i.e. ∞. This would imply that a 1% increase in price will lead to a situation where nothing is demanded. While in the case of supply, it implies the supplier will be willing to supply as much as possible.Fairly Elastic Case: this implies the 1% increase in price will lead to more than 1% decrease in quantity demanded. While in the case of supply, a 1% increase in price will lead to more than 1% increase in quantity supplied.Perfectly or Zero Inelastic Case: this is when the elasticity co-efficient is zero. This implies that changes in price have no effect on quantity demanded and supplied.Fairly Inelastic Case: this is when the elasticity co-efficient is greater than positive but less than one. This implies that a given change in price will lead to less than a proportionate change in quantity demanded or supplied.Unitary Inelastic Case: if elasticity co-efficient is one (unity), it means that a given percentage change in price gives rise to the same percentage change in quantity demanded or supplied.But, it must be noted that elasticity is dimensionless, that is it has no specific unit of measurement, and can only be interpreted in terms of percentage and as a result, it must be measured in percentage terms. Besides, the advantage of using percentages is that it affords a common basis for comparison. It must be equally noted that for cases of price elasticity of demand, the solutions must be preceded by a minus. This is because it follows certain logical consequences of arithmetic operation, as well as a theoretic economic rationale; the inverse relationship between price and demand. Although, this sign may be ignored in some cases, where the analytical results states otherwise, but the interpretation of such cases should be clearly spelt out. Meanwhile, for the price elasticity of supply, the use of a plus or positive sign preceding the coefficient is required. This is because of the direct relationship between price and supply; but, where the analytical results states otherwise also, the interpretation of result should justify such position[4].Finally on the issue of price elasticity, there is also the concept of cross-price elasticity of demand for say good X and Y(EXY), which measures the percentage change in the quantity of good X as a result of a change in the price of good Y. Operationally, it is given as:

= the elasticity of income, Q = quantity demanded,M = money income,

= the elasticity of income, Q = quantity demanded,M = money income, = is used to denote change or difference.The concept of income elasticity is important in many respects. First, it shows the degree of responsiveness in the demand for any good to changes in income. Therefore, it means a 1% change in the income of consumer, ceteris paribus, will lead the consumer to increase the demand for a particular commodity. Besides, the unique solution arrived at in the course of calculations could take four different forms:Normal Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is greater than zero (that is ɛM > 0), it implies that the good is normal or superior. This means that the higher the income, the same or little more quantity of a particular product will be preferred. For instance, basic needs such as food, clothing, shelter, health, clothings, e.t.cInferior Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is less than zero (that is ɛM < 0), it implies that the good is inferior. This means that the higher the income, the lesser quantity of a particular product will be bought. For instance, second-hand productsLuxury Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is greater than one (that is ɛM > 1), it implies that the good is luxury one. This means that the higher the income, the higher quantity of such a particular product will be bought. For example cars, holiday travels, etcNecessary Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is less than one (that is ɛM < 1), it implies that the good is necessary good or above normal or more than superior good. This means that whatever the state of your income, they are class of goods that you just cannot do without them. Examples include salt, clothings, transport fares, e.t.c,[10].In real world cases, a good analysis of elasticity carried out could guide investors and business persons on which areas to invest or divest. This is because, areas that have income-backed demand are very vital to the success of any venture. Thus, if a good is found to be strongly income elastic at any given income price, demand for it will shift outwards as income increases, thereby, influencing sales, revenue and profit.Aside the regular elasticity measurements, there is also the elasticity of intertemporal substitution- where it is possible to consider the combined effects of two or more determinant of demand. The steps are as follows: Step 1: Given the Price Elasticity of Demand Equation(εd), then,

= is used to denote change or difference.The concept of income elasticity is important in many respects. First, it shows the degree of responsiveness in the demand for any good to changes in income. Therefore, it means a 1% change in the income of consumer, ceteris paribus, will lead the consumer to increase the demand for a particular commodity. Besides, the unique solution arrived at in the course of calculations could take four different forms:Normal Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is greater than zero (that is ɛM > 0), it implies that the good is normal or superior. This means that the higher the income, the same or little more quantity of a particular product will be preferred. For instance, basic needs such as food, clothing, shelter, health, clothings, e.t.cInferior Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is less than zero (that is ɛM < 0), it implies that the good is inferior. This means that the higher the income, the lesser quantity of a particular product will be bought. For instance, second-hand productsLuxury Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is greater than one (that is ɛM > 1), it implies that the good is luxury one. This means that the higher the income, the higher quantity of such a particular product will be bought. For example cars, holiday travels, etcNecessary Good: In a situation where the elasticity of income is less than one (that is ɛM < 1), it implies that the good is necessary good or above normal or more than superior good. This means that whatever the state of your income, they are class of goods that you just cannot do without them. Examples include salt, clothings, transport fares, e.t.c,[10].In real world cases, a good analysis of elasticity carried out could guide investors and business persons on which areas to invest or divest. This is because, areas that have income-backed demand are very vital to the success of any venture. Thus, if a good is found to be strongly income elastic at any given income price, demand for it will shift outwards as income increases, thereby, influencing sales, revenue and profit.Aside the regular elasticity measurements, there is also the elasticity of intertemporal substitution- where it is possible to consider the combined effects of two or more determinant of demand. The steps are as follows: Step 1: Given the Price Elasticity of Demand Equation(εd), then,

represent money income,

represent money income,  represents quantity of cars demanded,

represents quantity of cars demanded,  represent elasticity of money, while

represent elasticity of money, while  is used to denote change or difference.

is used to denote change or difference.

Thus, the regression analysis was carried out on the qualitative data obtained to show the direction and magnitude of causation amongst the selected variables; specifically, old, present and future incomes of the lecturers were regressed on the present number of cars, (see Appendix 2 for respondents’ information) and the following results were discovered:From table 2, it can be deduced from the correlation (R = 0.725) that the relationship between income and the demand for cars among OAU is positive and high at 72.5%. Besides, the proportion of income received that explains the demand for cars by the lecturers in OAU is about 52% (as depicted by R square=0.526) and with some adjustments in the R squared, the proportion of explanation is reduced to 45.9% (as shown by Adjusted R Squared).

Thus, the regression analysis was carried out on the qualitative data obtained to show the direction and magnitude of causation amongst the selected variables; specifically, old, present and future incomes of the lecturers were regressed on the present number of cars, (see Appendix 2 for respondents’ information) and the following results were discovered:From table 2, it can be deduced from the correlation (R = 0.725) that the relationship between income and the demand for cars among OAU is positive and high at 72.5%. Besides, the proportion of income received that explains the demand for cars by the lecturers in OAU is about 52% (as depicted by R square=0.526) and with some adjustments in the R squared, the proportion of explanation is reduced to 45.9% (as shown by Adjusted R Squared).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML