-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2013; 3(5): 199-209

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20130305.01

The Effect of Trade Liberalisation on Some Selected Poverty Indicators in Nigeria (1980-2009): Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) Approach

Anthony Enisan Akinlo, Gabriel Adeleke, Aremo

Department of Economics, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Anthony Enisan Akinlo, Department of Economics, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The paper examined the effect of trade liberalisation on some key identified poverty indicators in Nigeria within the period of 1980 and 2009 with a view to determining whether the trade policy as practised in Nigeria over the study period has really significantly impacted on the state of poverty. The methodology applied was Generalised Method of Moments. The findings show that trade liberalisation, in Nigeria, did not contribute significantly to poverty reduction. It is therefore pertinent that a firmer and realistic approach aimed at regularly assessing the progress made in implementing trade liberalisation programmes through effective supervision and monitoring of programmes directed at reining in on poverty be pursued.

Keywords: Trade Liberalization, Poverty, Nigeria, GMM Approach

Cite this paper: Anthony Enisan Akinlo, Gabriel Adeleke, Aremo, The Effect of Trade Liberalisation on Some Selected Poverty Indicators in Nigeria (1980-2009): Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) Approach, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 3 No. 5, 2013, pp. 199-209. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20130305.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The available theoretical literature presents conflicting views on the effect of trade liberalisation on poverty in both developed and developing countries. The first view argues that trade liberalisation contributes to the enhancement of poverty reduction ([1][2]). The second view claims that trade liberalisation tends to make the poor poorer and the rich richer; thus widening economic inequality among the people ([3][4] and[5]). As argued by[4], trade liberalisation is capable of creating “the poorer” out of the poor despite the overall improvement in the general welfare of the entire poor. This obverse view also claims that trade liberalisation does not lead to poverty reduction. For instance,[6] argues that trade liberalisation will increase urban poverty. A similar view is expressed in a study by[7]. The third view shows mixed results meaning that trade liberalisation may or may not after all influence poverty ([8];[9] and[10]).The available empirical evidence is inconclusive regarding the relationship between trade liberalisation and poverty. As argued by[11] there is no strong evidence that trade liberalisation will deepen poverty or vulnerability; and there is no guarantee either that the poor will always benefit from trade liberalisation. Moreover, different households may be affected differently by the practice of trade liberalisation.The emerging consensus in less developed countries seems to be that the distributional and poverty impacts of trade liberalisation depend crucially on the structure of initial protection, the pattern of liberalisation, and thecharacteristics of the country in particular the functioning of the labour market and the sectoral as well as skill composition of the work force ([10][12][13]). This present study which aims at determining the effects of trade liberalisation on some selected poverty indicators in Nigeria makes significant empirical contribution in two areas. First, it contributes to the literature by addressing the controversies that surround the relations between trade liberalisation and poverty level in Nigeria. Second, the Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) estimator adopted in the analysis has some attractive features. GMM obviates the need to specify distributional assumptions such as normal errors. Also, it provides a unifying framework for the analysis of many familiar estimators such as ordinary least squares (OLS) and instrumental variable (IV). Furthermore, it offers a robust method of estimation in a situation where the traditional methods appear computationally cumbersome. In addition, the approach affords the opportunity to specify an economically interesting set of moments, or a set of moments believed to be robust to misspecifications of the economic or statistical model[14].The remaining part of the paper is organised into five sections. In section 2, a brief summary of the theoretical and empirical issues on the relationship between trade liberalisation and poverty indicators is provided. The specification of the model is contained in Section 3. Section 4 provides the empirical results, while the last section contains the conclusion.

2. Theoretical Framework and Empirical Issues

2.1. Theoretical Framework

- The theoretical links between trade and poverty found expression in trade policy issues that focus mainly on income distribution[15]. Theoretical models of Stolper-Samuelson and specific factor models focus on the distributional consequence of trade. This model is a variant of the Ricardian model, which is referred to as Ricardo-Viner model[16].[17] and[18] developed the mathematical version of the model which focuses on the short run implications of international trade on income distribution. The specific factor model is hinged on the assumption of a two industry economy that produces two goods namely; an exportable commodity and an import substitution commodity. And within the competitive market framework, two factors of production labour and capital are used in production. It is further assumed that in the short run, only one factor, i.e. labour, is mobile within industries, while capital is specific and primarily immobile between industries. In addition, full employment is assumed in the market, suggesting that the sum of labour demand in each industry is necessarily equal to labour endowment. Besides, the assumption of homogeneity of labour is recognised.The model indicates that more labour will be attracted to export industries due to wage increases resulting largely from free trade as relative prices of exportable commodities increase. On the other hand, the import substitution industries suffer as profits decline. The real return to capital in the export industries will potentially rise while the return to capital in the import competing industry tends to fall with respect to purchases of both exports and imports. This leads to some form of income redistribution. This phenomenon favours capital owners in the export industry at the expense of capital owners in import substituting industry. The income distribution pattern among workers is rather uncertain. This largely depends on the consumption pattern of workers in respect to the volume of exportable commodity, import substitution commodity or the combination of the two. The real wages of workers will likely increase in respect of import substitution commodity prices and decrease in respect of exportable commodity prices.

2.2. Empirical Issues

- [19] argued that the linkages between trade liberalisation and poverty alleviation are not as direct or immediate as the linkages between poverty alleviation and national policies on education and health, land reforms, micro-credit, infrastructural development and governance. He observed that trade liberalisation could affect the income distribution of the poor in a number of ways but the final outcomes of this depends largely on the relationship between trade liberalisation and growth on the one hand and trade liberalisation and income distribution on the other hand.[19] argued that trade liberalisation creates conditions for faster income growth through better access to ideas, technology goods, services and capital. Trade could equally promote growth by boosting efficiency in the use of resources not only through specialisation but also by permitting the realisation of economies of scale and the feasibility of convergence in income between the rich and the poor.The study by[20] examined the impact of free trade area (FTA) encompassing foreign direct investment liberalisation, trade liberalisation, foreign direct investment (FDI) facilitation and economic cooperation in East Asia. The study is crucial because FTAs have become increasingly important in East Asia in the recent times. The study adopted Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) based on Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) model. The result that emerged from the analysis suggested that the larger the coverage in terms of membership and contents such as trade and foreign direct investment liberalisation, facilitation and economic cooperation, the greater the benefits accruable to member countries.The study by[21] investigated the impacts of trade liberalisation in Egypt and arrived at a similar result as[20]. Specifically,[21] focussed on the allocative effects of trade policy reforms along with the associated changes in economic welfare in Egypt using Egyptian CGE-TL model. On the basis of this, they carried out simulations with various scenarios. They found that bilateral liberalisation with the EU would tend to reduce Egyptian welfare marginally; although the ultimate effect depends considerably on the extent of market accessibility that EU could validly provide. The study concluded that the extent of gains accruable to the Egyptian economy would depend largely on the policy options adopted by the government that could serve as a counter-cyclical device to off-set any loss from trade agreement with EU.The study by[1] examined the impact of agricultural liberalisation by Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries on poverty in Uganda and compared this to the poverty impact of all merchandise trade liberalisation on poverty. The analysis was done within the framework of CGE. The result showed that the overall impact of OECD merchandise agricultural trade liberalisation had a positive impact on people’s welfare. However the poor appeared to be worse-off. On the other hand, agricultural liberalisation in OECD countries had adverse effect on the welfare of all people in Uganda irrespective of household poverty status, residence and region. This reduction in welfare has been attributed largely to the subsistence nature of agriculture in the Uganda.The above study, compared to[22], which examined the impact of rice trade liberalisation on poverty in Asia using descriptive analysis. The study showed that in a competitive market situation, the immediate impact was through a change in price levels resulting from increase in export demand. The sellers rather than buyers benefitted in this case unlike in a non-competitive case, where importation of goods and services was considerably encouraged. The effect of this is to depress the high domestic prices to maintain equality with world prices. The consumers are favoured under this situation. The derived fact from[22] is that it is possible within a country to have both losers and gainers within the framework of trade liberalisation. It is, however, difficult to predict the net gainers.[23] investigated the impact of trade liberalisation on poverty and inequality in Ethiopia within the framework of micro simulation analysis which was based on 2001/2002 Social Accounting Matrix (SAM). The findings from this study revealed that full liberalisation tended to dampen the domestic production of manufactured goods. This was because the demand for domestic goods tended to decline as consumers shifted to cheap imported commodities. The result of micro simulation suggested that welfare of farm households could improve after 100 percent tariff cuts. On the contrary, the welfare of wage earner household tended to decline, while that of entrepreneur remained the same. The findings of[23] tend to suggest that the welfare effects of trade liberalisation on household depend remarkably on the composition of the household.[24] investigated the relationship between trade liberalisation and poverty. He surveyed the relationship by re-visiting the age-old debate connecting the two. He argued that trade and openness remained the engines of growth and important instruments of development, noting that an inward looking development strategies were not a sensible policy option.[25] was of the opinion that trade liberalisation is crucial to any growing economy. He argued that the weight of evidence suggested that trade liberalisation alone might not lead to trade and income growth on a sustained basis, let alone alleviate poverty.[24] argued that trade liberalisation must be complemented with other policies to ensure that effective integration into the world in a manner favourable to growth and poverty alleviation is achieved. Policies like strong institution, favourable investment climate, among others are recommended.The findings of[25] appeared more liberal and more specific than of[24]. He argued that the outcomes of trade liberalisation depend greatly on whether the forces of dynamic comparative advantage push an economy towards or away from the direction of activities that stimulate long run growth. The position of[26] was that there should be no theoretical presumption in favour of finding an unambiguous negative relationship between trade barriers and growth rates in the types of cross-national data typically analysed. The inference derived from[26] study is that there is no designable link between trade and growth; thus suggesting that the issue could only be settled empirically.[27] examined the impact of trade liberalisation on poverty in Bangladesh using descriptive analysis. The results from[27] showed that in Bangladesh, trade liberalisation contributed to growth of output and helped to reduce poverty.The findings of[28] are similar to that of[27].[28] focussed on application of a dynamic top-down CGEmicro-simulation model in Bangladesh economy. He examined the macroeconomic poverty and welfare impacts of complete and unilateral domestic trade liberalisation in Bangladesh over the last two decades. Two different poverty lines for rural and urban households were examined. The findings that emerged suggested that there were marked differences between the short- and long- runs impact of trade liberalisation. In the short run, it was observed that there could be welfare reduction and increase in poverty. On the other hand, in the long run, there could be welfare gains.The study by[29] they examined the impact of trade liberalisation on poverty and inequality in Nicaragua using the methodology of computable general equilibrium. In all the scenarios, and model runs, poverty level dropped by 1 percentage point, or less, caused by output and employment effects of trade liberalisation.The study by[30] investigated the effects of trade policies on poverty given the volatility of agricultural prices of grains, by considering whether these effects are invisible or not. The invisibility hypothesis was tested using stochastic simulation method. The test was based on comparison of two samples of price and poverty distribution. The results showed that the short run impacts of poverty of full trade liberalisation were distinguishable in only four of the fifteen countries considered. This suggests that moderate agricultural trade reforms impacts on poverty are likely to be invisible in the short run. In a similar study in Argentina using a country specific approach,[31] examined the impacts of trade liberalisationon poverty inequality. They found that trade liberalisation of world trade including subsidies and import taxes, both for agricultural and non-agricultural goods, reduced poverty and inequality in Argentina. However, if agricultural products were included, poverty and inequality worsened.In a study carried out in Mexico by[32] which investigated the effect of Mexico’s potential unilateral tariff liberalisation using CGE analysis. They found that tariff reforms would have effect on the welfare of the people by benefitting mostly the poorer deciles more than those in the richer ones.

3. The Model

- To examine the impact of trade liberalisation on some selected poverty indicators poverty indicators in Nigeria, the general model adopted takes the following form:POV IND =f (LEXCHRT, LEXR, LMS, LOPN, LRGDP, TLINDEX)It has been established in the literature that trade liberalisation heightens economic growth which in turn reduces poverty[33]. We relied on this assumption in formulating the poverty bloc equations. Thus, labour force participation rate (LLABFPR), real per capita consumption expenditure (LRPCEC), and life expectancy at birth (LLIFEP), could perfectly substitute for economic growth with the same a priori expectations. On the other hand, crude death rate has the opposite effect and thus has the reversed a priori expectations.The unrestricted poverty models1 are specified in the forms below:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

For equation 7,

For equation 7, For equation 8,

For equation 8, For equation 9,

For equation 9,

3.1. Variable Definitions

- Life expectancy variable (Lifes) which depicts the general health status is proxied as life expectancy (in years) and infant mortality rates (per 1000 live births).It is observed that other measures of variables are not consistent with changes in other measures of variables. Examples of these are variables like: life expectancy at birth, infant mortality rates, under-5 mortality rates, among others. Poverty is proxied as the level of employment which is defined as the labour force participation rate. The use of this proxy is informed by paucity of official employment data in Nigeria.Another Poverty indicator used in the study is real consumption expenditure per capita following previous studies by[34] and[35]. The two studies employed real consumption expenditure as an alternative to per capita income on the basis of consensus in the literature that an expenditure measure of poverty is superior to income measures.One measure of trade liberalization is openness. Openness is generally measured in two ways: i.e. in terms of policy and outcome measures[36]. There are however arguments about the superiority of one over the other in the literature (see[37] and[38]. Openness used as measure of trade liberalisation in this study was estimated from the output perspective for two reasons: first, there is no continuous long time series data on most of policy measures such as effective tariff rates on imports and exports. Second, a critical weakness of any measure based on tariffs is that the typical trade regime of developing countries restricts imports with other barriers. For many products, the tariffs are considerably redundant, thus they do not provide any additional protection for domestic producers. It becomes obvious therefore that unavailability of time series data on tariffs might not provide a valid indicator for trade liberalisation hence the choice of openness variable which proxies trade liberalisation.Another proxy for trade liberalisation is the trade liberalisation index which is represented as a dummy variable that takes the value of one for every year or quarter when there was trade liberalisation and zero elsewhere when there was no trade liberalisation in Nigeria.

3.2. Sources of Data

- The data on real gross domestic product, exchange rate, consumer price index degree of openness, money supply, and public expenditures were sourced from the International Financial Statistics (IFS) published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Central Bank of Nigeria Statistical Bulletin (various issues). Data on literacy rate, life expectancy, and employment were obtained from World Development Indicators (2009) and Human Development Indicators (2004).

3.3. Technique of Analysis

- The effect of trade liberalisation on sectoral output growth and some selected poverty indicators was achieved using the Generalised Method of Moments (GMM). The application of GMM to time series estimation has some attractive features. First, it avoids the need to specify distributional assumptions such as normal errors. Second, it provides a unifying framework for the analysis of many familiar estimators such as ordinary least squares (OLS), instrumental variable (IV). Third, it offers a robust method of estimation in a situation where the traditional methods appear computationally cumbersome. Fourth, it affords the opportunity to specify an economically interesting set of moments, or a set of moments believed to be robust to misspecifications of the economic or statistical model[42].

4. Empirical Results

- In this section, the results of the effects of trade liberalisation on some selected poverty indicators in Nigeria between 1980 and 2009 are presented. First, we present the result of disaggregated fluctuation measures of poverty indicators and volatility over the period 1980-2009. This is followed by the descriptive statistics of the variables, unit root tests and cointegration, and GMM results.

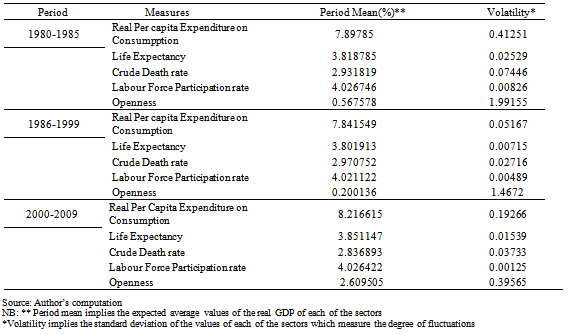

4.1. Analysis of Disaggregated Measures of Poverty

- The results of the disaggregated fluctuation measures of poverty indicators and volatility in Nigeria within the period of 1980 and 2009 are presented in table 1.The real per capita expenditure on consumption was 7.90 in terms of mean period average between 1980 and 1985. The fact that the oil boom of 1970s was still having the multiplier effect on the economy was enough for the mean value to assume such a positive effect on the economy in the 1980s.The corresponding volatility level was 0.41. The figure for the period between 1986, when SAP gained prominence, and 1999 had a period mean of 7.84. This represents a marginal decline of 0.8 per cent which is rather very low. The drop in mean value could be explained partly as the aftermath of the structural adjustment programme which was still having its toll on the domestic economy and economic agents. The effects in the period between 2000 and 2009 showed that the value picked up to 8.22 which could partly be ascribed to the positive impacts associated with SAP. However, the three period volatility figures were not stable. They ranged between 0.05 in 1986 to 1999 periods and 0.41 in 1980 to 1986 periods. In the period between 2000 and 2009 volatility level was 0.19. The lack of stability in real per capita expenditure could be linked to incessant changes in various governments fiscal, monetary and income policies implemented from time to time which greatly affected the disposable income and level of expenditure of Nigerians.

|

|

|

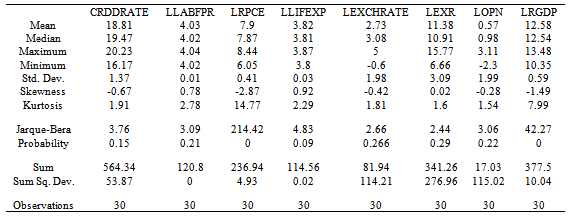

4.2. Descriptive Analysis of the Data

- Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the data series used in the analysis. For virtually all the data series, it is observed that the values of the means and median are very close. This is in line with the position of[39] that when a distribution is perfectly symmetrical, the mean, median and mode must converge; and in cases of near symmetry, the three measures are necessarily very close. It could rightly be deduced that the distributions of the series in table 2 are, in the main, nearly symmetrical. Skewness and Kurtosis provide useful information about the symmetrical nature of the probability distribution of the various data series as well as the thickness of the tails of these distributions respectively. These two statistics are particularly important as they are used in computing Jarque-Bera statistic, and also for testing the normality or asymptotic properties of a particular series. The econometric analyses are often based on the assumptions of normality and asymptotic properties of the data series. There is therefore the need to test for the existence or otherwise of these two properties because most probability distributions and test statistics like t, F, and are based on them.As tables 2 suggests, all the data series save those that are seasonally generated are normally distributed going by the null hypothesis that variables are normally distributed. The only variable that appears not to be seasonally motivated is money supply as the null hypothesis that variable is normally distributed was accepted. To obviate this normality problem, data series that did not pass the normality tests were seasonally adjusted for the purpose of analysis. In testing for the skewness of data series, we are guided by the fact that the skewness of a normal distribution is zero.

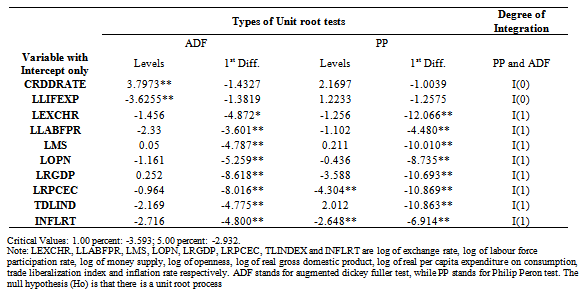

4.3. Unit Root Tests

- The results of the unit roots tests using Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) and Philips-Perron (PP) are as presented in table 3.From table 3, almost all the data series are integrated of order one. The two variables that appeared to be stationary in levels are crude death rate and life expectancy rate. This is to be expected as they are calculated in rates, thus they give the idea that they are in their first difference. It suggests that they are not equally stationary in their levels.

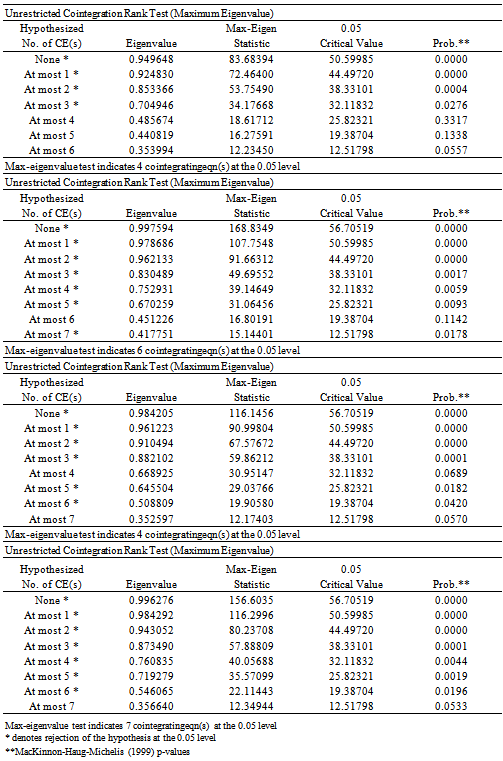

4.4. Cointegration Analysis

- The option of cointegration test chosen is the unrestricted cointegration rank test with the application of maximum eigenvalue approach. The variables contained in each of the models are jointly considered for the purpose of determining the number of cointegrating equations.The results of the Johansen cointegration show that all the four models had at least more than one cointegrating vector (see table 1 Appendix ). The conclusion could be drawn that all the variables in each of the multivariate models are cointegrated.

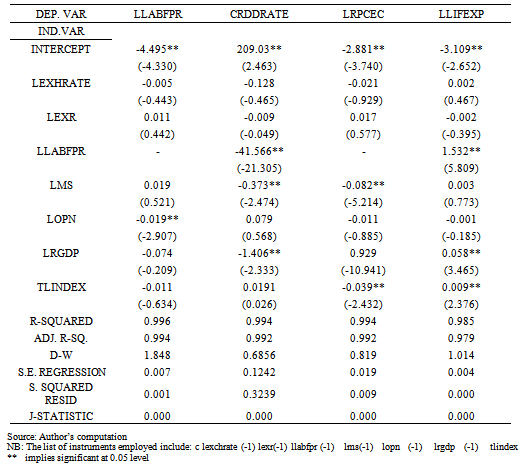

4.5. Results of Generalised Method of Moments (GMM)

- The results of the GMM analysis are presented in table 4. It is observed that the four models estimated are well-behaved in terms of goodness of fit suggested by high coefficients of determinations and adjusted R-Squared. Although elements of positive serial correlation were present, the use of GMM analysis however obviated the problems of violations of Ordinary Least Squares assumptions of no serial correlation. The robustness check conducted on the residuals from the GMM estimates depicts a case of heteroscedasticity. Thus Hansen’s J-test which is a more general test than the Sargan test was applied. The various instrument validity sensitivity tests rejected the maintained hypothesis that all the surplus moment conditions are valid. This is to be expected because the coefficients are exactly identified; thus theover-identifying test statistic J will be exactly zero as in these results[40]. This informed using the best and minimal instruments that are readily available i.e. a year period lagged values of the exogenous variables and the intercept.The trade liberalisation proxies entered the equations in two forms – as an outcomes variable of openness (OPN) and as a qualitative variable capturing all trade policy reforms that occurred between 1986 and 2009 which is proxied as trade liberalisation Index (TLINDEX). Since the two variables measured different aspects of trade liberalisation, both could validly be tolerated in a single model.In the labour participation rate (LLABFPR) equation, the only coefficient that is statistically significant is that of LOPN (Openness). The value of the elasticity coefficient is 0.02 with negative sign. This implies that a 10 per cent increase in openness led to 0.2 per cent reduction in LLABFPR i.e. labour participation rate. The trade liberalisation outcome of openness would not enhance the growth of the nation’s human resource development. This could occur when the capital inputs imported through trade liberalisation displaced the existing labour force rendering them unproductive.The exchange rate came out with statistically insignificant coefficient at 5 per cent and with negative sign. Similar result was obtained for external reserves variable although it conformed to the a priori positive sign. The coefficient is equally not statistically significant at 5 percent. The money supply (LMS) variable conforms to the a priori expectation of positive sign but statistically insignificant. The real GDP (RGDP) had counter-intuitive negative sign with 0.07 coefficient value.

|

5. Conclusions

- The paper investigates the impact of trade liberalisation on some selected poverty indicators in Nigeria over the period 1980-2009 using the Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) technique. The empirical results show that trade liberalisation does not contribute significantly to the enhancement of labour participation rate in Nigeria. In the same way, trade liberalisation does not seem to contribute positively towards reduction in crude death rate real per capita expenditure on consumption in Nigeria. However, trade liberalisation has marginal positive effect on the life expectancy of the people. In general, these findings could be interpreted as evidence that an increase in trade liberalization may not necessarily lead to reduction in poverty and increased welfare.What this suggests is that some other factors need to be taken into consideration in the implementation of the trade liberalization policies in the countries. In particular, the subsistence nature of agricultural production in developing countries, Nigeria inclusive needs to be taken into consideration in the implementation of trade liberalization policies. Moreover, the pattern of trade liberalization and the labour market and sectoral as well as skill composition of the work force should be considered for trade liberalization to achieve the desired goal of poverty reduction and increased welfare in the country.

Appendix

Notes

- 1. The model specification for models 6 to 9 was informed by the omitted and redundant variable tests carried out to obtain an optimal model selection of the exogenous variables based on Wald test. This is why an exact number of independent variables is not obtained in some of the models.2. The interpretation of CRDDRATE equation follows that of linear-log model; thus each of the coefficients is divided by 100 or multiplied by 0.01 before interpretation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML