-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2013; 3(2): 90-99

doi:10.5923/j.economics.20130302.05

Assessing the Effects of Corporate Governance Attributes on the Quality of Directors-Related Information Disclosure: The Empirical Study of Malaysian Top 100 Companies

Juliana Anis Ramli 1, Khairul Nizam Surbaini 2, Mohd Ismail Ramli 3

1Department of Accounting, Universiti Tenaga Nasional, Muadzam Shah, 26700, Pahang, Malaysia

2Department of Marketing & Entrepreneur Development, Universiti Tenaga Nasional, Muadzam Shah, 26700, Pahang, Malaysia

3Faculty of Accountancy, Universiti Teknologi Mara, 40450, Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Juliana Anis Ramli , Department of Accounting, Universiti Tenaga Nasional, Muadzam Shah, 26700, Pahang, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study attempts to investigate the effects of corporate governance (CG) mechanisms towards the quality of directors-related information (DRI) disclosure of Malaysian Top 100 companies, after controlling variables of firm-specific characteristics such as firm size and auditor size. A DRI disclosure was measured using scoring worksheet developed by Ramli (2001) to score the items in the corporate annual reports. Consistent with expectations, the Spearman correlation showed there are statistically proven the positive associations between board independence, board diversity managerial ownership and DRI disclosure at 5 percent level, with the exception of CEO duality. The result appears to suggest that there were positive impact of the CG mechanisms on the quality of DRI disclosure among Malaysian Top 100 largest companies which were ranked by the Minority Shareholders Watchdog Group (MSWG) based on their market capitalisation. However, the regression model reported R2 of 38.1 percent which means that almost 62 percent of those factors influencing the DI disclosure have not been captured by the model. These other factors may perhaps be identified through future research involving larger sample or other research method such as by questionnaire surveys or interviews.

Keywords: Corporate Governance, Quality, Director, Information, Disclosure, Top Companies, Malaysia

Cite this paper: Juliana Anis Ramli , Khairul Nizam Surbaini , Mohd Ismail Ramli , Assessing the Effects of Corporate Governance Attributes on the Quality of Directors-Related Information Disclosure: The Empirical Study of Malaysian Top 100 Companies, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 90-99. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20130302.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction & Problem Statement

- The Asian economic crisis occurred in 1997 coupled with the collapse of the giant corporate scandals such as Enron, WorldCom, Parmalat, etc. have left deep scars on the Malaysian corporate world as well. One of the key factors that lead to these accounting scandals was weakened corporate governance (CG) system. This had resulted to the tremendous impact to the economy as a whole, which through its effect on the capital markets. Referring to the US corporate scandals, the Malaysian government has taken prompt initiatives in a way to ‘learn a lesson’ by improvising its CG and transparency among companies through the establishment of the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance (MCCG) that was introduced by the Finance Committee on Corporate Governance in 2002. In addition, Corporate Market Plan (CMP) has been set out by the Securities Commission (SC) to make better strategies for Malaysian capital market for 10 years ahead and also to strengthen CG to achieve realistic expectations of SC in improving the investor relations and simultaneously to boost the Malaysian economy.Given the increasing need for better CG practices and disclosure transparency, in tandem with the vision 2020, SC has recently set out its sophisticated regulatory framework namely “Corporate Governance Blueprint” to maintain the relevancy and its effectiveness in CG practices. One of the five underlying CG systems included in this framework is disclosure and transparency standards. In this context, the framework highlighted that the quality of disclosure is measured based on how the information is useful to the shareholders in assisting them in making sound decisions. Besides, CG has also been critically important to other stakeholders such as creditors, employees, regulators, governments, etc. As far as the market capital efficiency and the allocation of resources are concerned, numerous studies have placed greater emphasis on the importance of transparency disclosure and financial reporting on protecting the interest of the shareholders. As such, previous studies have been empirically suggesting that the increased disclosure helps the companies to reduce the cost of capital (Botosan, 1997, 2000), able to raise capital at the lowest cost (Healy and Palepu, 1993), and to reduce the cost of debt capital (Sengupta, 1998), as a strategic tool to convince the capital market and ultimately lead to the enhancement of the share values (Gigler, 1994; Barako, Hancock and Izan, 2006). Further, MCCG 2000 has been revised to MCCG 2007, and to date MCCG 2012, which requires the companies to comply more than as what is being prescribed by the regulatory bodies. Adoption of basic information disclosure requirement in the annual reports cannot be concluded as a higher level of disclosure and any excess of the mandated information in compliance with the standards, is regarded as voluntary basis information. The motivation of companies to voluntarily disclose corporate information is subject to the discretionary actions of the managers, such as the use of disclosure as a signal of firm value (Hughes, 1986). In fact, the MCCG 2012 focuses on elucidating the roles of the board of directors to deliver their commitment in protecting the shareholders’ rights and monitoring the activities and tendency of management to act at its opportunistically behaviour. The relationship between directors (agents) and shareholders (principals) has been widely discussed in the issues of CG in which the divergence between ownership and control and the expropriation of shareholders’ interest may lead to the agency problem and ultimately has given rise to the agency costs (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Hence, to mitigate this agency problem, better disclosure and transparency of financial reporting are essentially required in practice to reduce the information asymmetry between the principal-agent relationship, even though the conflicts are not perfectly being resolved. Better disclosure or buzz word ‘transparency’ is defined as the availability of firm-specific information provided to shareholders and even stakeholders of publicly traded firms (Bushman, Piotraski & Smith, 2004) and it is perceived as a way to regain the shareholder’s confidence to invest in the capital markets (Maria, et.al., 2005). Further, disclosure and CG mechanisms are also seen as a complementary tool in reducing the agency problem. This has been supported by Ho and Wong (2001) that both elements are complementary when the expected of the extent of disclosure is higher when the CG mechanisms exert their influence for greater oversight the management activities and thereby to act align with the shareholders’ interests. In light of that, as being stipulated in the MCCG 2012, it requires the companies to produce a timely and balanced disclosure as to promote the companies for better CG practices in a way of protecting the shareholders at their best interests. In fact, the assessment of Malaysian Corporate Governance (MCG) Index 2011 has been conducted by Malaysian Minority Shareholders Watchdog Group (MSWG) in a mission to uphold in strengthening the compliance of CG principles and practices which sub-divided into four sections; board of directors, directors’ remuneration, shareholders and accountability and audit. Amongst those assessments, ten companies have achieved the highest total scores in the assessment of the quality of disclosures and market conduct; in return, they have been awarded some accolades to advocate their best practices (MCG Index Report 2011). This signifies in the sense that how well and concern the regulatory bodies have been put in place to promote and enhance the disclosure and transparency practices among the companies to facilitate the shareholders in making an informed and sound decision. Several previous studies have extensively debated on the importance of CG mechanisms to the voluntary disclosure. Most of the researches have been focused on the developed countries (i.e. Cerf, 1961; Botosan, 1997; Lang & Ludholm, 1993; Singhvi & Desai, 1971; Forker, 1992, Baek, Johnson & Kim, 2009; Bujaki & McConomy, 2002; Ben-Amar & Bujenoui, 2006; Maria, Manal & Ljungdahl, 2005), few studies on emerging markets (i.e. Ho and Wong, 2001; Huafang & Jianguo, 2007; Cheung, Jiang & Tan , 2010), with few studies in developing countries (i.e. Haniffa and Cooke, 2005; Akhtaruddin, Hossain, Hossain & Yao, 2009; Karagul and Yonet, 2011; Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, 210; Bhasin, 2012; Samaha, Dahawy, Hussainey & Stapleton, 2012; Wan Mohamad & Sulong, 2010). In Malaysian context, Akhtarudin et.al. (2009) and Wan Mohamad & Sulong (2010), have undertaken on measuring the impact of CG on voluntary disclosure of corporate practices and their findings contribute to the mixed results. Most of the prior studies which attempted to measure the extent of voluntary disclosure are using dummy variable (score “1” for disclosed item or “0” for otherwise). However, since the degree of compliances and level of directors-related information (DRI) is used as a proxy of quality, hence this study is using the measurement of sub-elements contained in each disclosure item at possible maximum point of 10. Even though, this area of voluntary disclosure on corporate governance practices provides abundant contribution to the growing literatures, however, researches that investigating on the directors-related information particularly, is still found lacking in the current literatures. From the assertion of agency theory that disclosure helps to mitigate the agency conflicts, hence the researchers aim to investigate the influence of CG attributes to the quality of DRI disclosure among MCG Index 2011 top 100 companies, after controlling the firm-specific characteristics with the disclosure, since the researchers do not find the similar study done in Malaysia. In a nutshell, CG mechanisms are always perceived as monitoring ‘packages’ to have control over the management activities so that the likelihood to fulfil the interests of the shareholders requiring for greater disclosure also could be enhanced. In this study, board characteristics (proxied by board independence, CEO duality and board diversity) and ownership structure (proxied by managerial ownership) are included as explanatory variables for the quality of directors’ information disclosure. Several previous studies have documented the association between voluntary disclosure and board characteristics (Eng and Mak, 2003; Chen and Jaggi, 2001 ; Chow and Wong- Boren, 1987; Cheng and Courtenay, 2004; Ho and Wong, 2001; Byard et.al., 2006; Kelton and Yang, 2008) and ownership structure (Eng and Mak, 2003; Huafang and Jianguo, 2007; Kelton and Yang, 2008). Ownership structure can be treated as a complement or substitute to the board characteristics in assessing their influence towards the voluntary disclosure (Core, Holthausen & Larcker, 1999). It is expected that DRI disclosure is negatively associated with the managerial ownership, in the sense that when the managerial ownership falls, thus the incentive of the managers to maximise their job performance simultaneously the shareholders’ value also would be dwindled. This would require for greater monitoring activities for their opportunistic behaviour, thus the higher level of information disclosure also will be needed. Apparently, the presences of independent directors to bring the objectivity in the board’s decision and women directors on the boardroom may give positive impact towards the voluntary disclosure level and even to other CG practices. On the other hand, the presence of role duality on the board also may impair the credibility of the directors in protecting the shareholders value, in the notion that the directors who holds role duality tends to withhold the information from the shareholders. Furthermore, the firm’s decision to voluntarily disclose information depends on specific- characteristics of the firm. Thus, we address this issue by adding control variables of firm-specific characteristics such as firm size and auditor size in this study.This study is expected to contribute to the existing literature in several ways. Firstly, we are not aware of any prior studies investigating the CG attributes and the disclosure quality of directors-related information, thus this study may provide a novel contribution to the literature. Secondly, previous studies have well-documented on the measurement of voluntary disclosure items using the checklist or scoring sheet and usually dummy variable of which “1” is awarded for each item being disclosed in the annual reports or “0” for otherwise. This paper is also hoped can provide useful insights to the regulatory bodies or interested parties i.e. shareholders for this contribution of measurement that can be used to asses quality of other CG practices among Malaysian companies.The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature that addresses board characteristics and DR disclosure which lead to the development of hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the sample selection, data collection procedure and the measurement of variables. Section 4 presents the analysis of findings and discussion of the results. Finally, section 5 concludes the study and sets out the limitations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review & Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Quality of DRI Disclosure

- Financial reporting and disclosure are seen as a potential channel for the companies to communicate its socially and financially activities to the outsiders. The companies usually provide disclosure through its medium of reporting financial information i.e. annual reports which including financial statements, footnotes, management discussion and analysis (Healy and Palepu, 2001). Agency theory posited that the divergence between ownership and controlling activities between agent and principal may lead to the agency problem. In such a way, companies take prompt initiatives to voluntarily disclose their corporate information in excess to the mandatory disclosure requirements by the regulatory bodies, can take in various forms of disclosure information, such as Internet financial reporting (IFR) disclosure (i.e. Kelton and Yang, 2008; Al-Russi, Selamat and Mohd Hanaefah, 2011, Almilia, 2009; Debreceny, Gray and Rahman, 2002), corporate social reporting (Adams, 2004; Haniffa and Cooke, 2005), environmental reporting (Sun, Salama, Hussainey & Habbash, 2010; Halme and Huse, 1997; Gibson and O’Donovan, 2007). However, the studies in relation to the directors-related information is still found lacking in the literatures, thus this matter warrants us to conduct this research. Us studies have been done on measuring the influence of corporate governance mechanisms on voluntary disclosure (i.e. Ahmed and Courtis, 1999; Healy and Palepu, 2001; Ho and Wong, 2001; Haniffa and Cooke, 2002, Chau and Gray, 2002; Chen and Jaggi, 2000; Barako et.al., 2006; Samaha et.al., 2012). The study done by Ben Amar and Boujenoui (2006), investigate the determinants of CG disclosure quality for a large sample of Canadian listed firms and they measure the firm level of CG disclosure quality using Globe and Mail annual CG disclosure score. They find that quality of CG disclosure of the Canadian firms has shown an improvement between year 2002 and 2004. The same finding has been found in the longitudinal study done by Nicolo, Laeven & Ueda (2008), their empirical findings suggest the improvements in CG quality in almost all the countries has a positive and significant effect on all measures of macroeconomic outcomes. Some of the studies are measuring the transparency disclosure and split them into mandatory and voluntary disclosure. For instance, Cheung et.al. (2010) reveal their findings that there is a positively correlated between company transparency and market valuation. In addition, they split the transparency index into mandatory and voluntary disclosure index and further they find that market valuation only related to voluntary disclosure index and those companies with the separation roles between CEO-Chairman tend to disclose more on voluntary basis information. In the Malaysian context, Wan Muhammad & Sulong (2009), measure the level of CG disclosure between small and large companies, and between the year 2002 and 2006. Their results suggest that large companies tend to disclose more on CG information rather than small companies; and companies in the year 2006 have better disclosure with regards CG matters in the annual reports instead of in the year 2002. This reveals during the year 2006, the Malaysian companies have shown remarkable improvements in their CG practices in following to the enhancement of regulatory bodies’ requirements to improve the quality of disclosure as a way to regain the shareholders’ trust and confidence simultaneously to advocate the increasing value and image of the firms, as compared to the year 2002. This study also aims to measure the quality of disclosure concerning the directors-related information since the directors are perceived as part of CG pillars and plays critical roles in overseeing the comprehensive activities performed by the management and acting as on behalf of the shareholders (principal) and other stakeholders. Therefore, all the information that pertaining to the directors’ affairs such as their personal backgrounds, remuneration, and also their involvement in committees that relates to the CG system such as nomination committee, audit committee, remuneration committee, statement of internal control, are treated as disclosure items which are measured using disclosure scoring worksheet developed by Ramli (2001) in order to develop a disclosure index for sample companies.

2.2. Corporate Governance Variables – Board Independence

- From the assertion of agency theory, the separation between ownership and control has increased the gap between the principal-agent relationships. The agency theory implies that firms exert their efforts to enhance the corporate disclosure in order to reduce the agency costs and pressures from the regulatory bodies. The presence of independence directors (INED) is very crucial to bring the objective judgement from the decision made by the board. Since they are carrying out their duties and responsibilities as a better monitoring function, thus are independent representatives of shareholders’ interests (Pincus, Robansky & Wong, 1989). Prior studies have proven that the presence of INED empirically is positively correlated with the increasing of better voluntary disclosure (Chen and Jaggi, 2000; Ben-Amar & Bonjenoui, 2006; Huafang & Jianguo, 2007; Akhtaruddin et.al., 2009;Samaha, et.al., 2012; Karagul & Yonet, 2011). Beasley (1996) reports that the frauds in the financial statements can be mitigated with the greater proportion of INEDs. However, some studies fail to document the positive association between the higher proportion of INEDs on the board and the extent of the disclosure (i.e. Ho & Wong, 2001; Barako et.al., 2006; Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, 2010; Wan Muhammad & Sulong, 2010). Based on the mixed results above, it is posited that:H1: The higher proportion of INEDs on the board is positively associated to the quality of DRI disclosure.

2.2. Corporate Governance Variables – Role Duality

- There are two kinds of leadership structure; combined structures and separated structure (Coles, et.al., 2001). The phenomenon when the CEO is also chair of the board is known as ‘role duality’ or combined structures. Forker (1002) argues that this ‘dominant personality’ has been found to be associated with poor disclosure. Haniffa and Cooke (2002) advocate that the board’s effectiveness in governance functions may be compromised due to this role duality since the CEO will be able to control the board activities and even the nomination of board members. Ho and Wong (2001) suggest that the person who occupies combined roles would tend to withhold unfavorable information to shareholders, and Barako et.al. (2006) argue that the likelihood to engage in opportunistic behavior also will be higher since he/she has to monitor both decisions and actions. Prior studies on the association between role duality and voluntary disclosure produced mixed results. Some studies documented the significant-negative relationship between the disclosure quality and CEO duality (Ben-Amar & Bonjenoui, 2006; Samaha et.al., 2012; Gul & Leung, 2004), while other studies failed to find any significant relationship between the two variables (Ho & Wong, 2001; Haniffa & Cooke, 2003; Cheng & Courtenay, 2006; Wan Muhammad and Sulong, 2010; Abad Navarro & Urquizza, 2009). However, Karagul and Yonet (2011) find weak evidence that the separation of both roles enhances the extent of disclosure. Hence, based on the arguments above, it is posited that:H2: The presence of role duality on the board is negatively associated to the quality of DRI disclosure.

2.4. Corporate Governance Variables – Managerial Ownership

- Managerial ownership is a substantial proportion of shares held by managers, including directors and supervisors. Since the ownership and control are separated, this concentrated ownership help to reduce the agency costs when the unscrupulous managerial actions will give bad impact to the managers itself (Jensen and Meckling, 1976), thus urge the managers to act align with the interests of the shareholders, thereby the need for monitoring will be reduced and thereby increased disclosure would take the place. The monitoring activities by the diffused ownership that would resulted the increasing costs borne by the firm and to reduce it through the incentives to provide greater voluntary disclosure (Eng & Mak, 2003). Thus, disclosure is somewhat perceived as a substitute device for the monitoring actions (Samaha, et.al., 2012). On the other hand, Ben-Amar & Bonjenoui (2006) suggest that the demand for high quality of CG disclosure will be increased when managers’ shares ownership is low, and vice-versa thus may signify that managerial ownership acts as a substitute for the voluntary disclosure. Similarly, Eng and Mak (2003) find the negative association between the two variables. However, some studies find weak evidence on the links between the two variables in the conception that managerial ownership is not significantly related to the disclosure (i.e. Huafang & Jianguo, 2007; Kelton & Yang, 2008; Samaha et.al., 2012). These findings give some indications that managerial ownership will affect the way directors-related information being disclosed. Thus, based on the arguments above, it is posited that:H3: The higher proportion of managerial ownership is negatively associated to the quality of DRI disclosure.

2.5. Corporate Governance Variables – Board Diversity

- Board diversity is defined as the presence of women directors on the board to bring some values in the organisation through their ideas contribution and different perspective (Adams & Fereira, 2009) and expose the companies with the greater opportunities in the world of competition (Fodio & Oba, 2012). In fact, numerous studies provide some evidences that the presence of the women directors on the board is associated with the increasing the firm’s value (Kang, Cheng & Gray, 2007; Erhardt & Werbel, 2003), philantrophic activities (Coffey & Wang, 1998; Fodio & Oba, 2012), community involvement and employee benefits (Bernadi & Threadgill, 2010) and share price informativeness to increase public disclosure in large firms (Gul, Srinidhi & Ng, 2011). Furthermore, Fodio and Oba (2012) document that having women directors in the boardroom is positively associated with the corporate’s philanthropy. Similarly, Bernadi & Threadgill (2010) report that the association between the number of female directors and the extent of disclosure on corporate social commitment is empirically found positively significant. In contrast, Nalikka (2009) do not find any statistically significant association between the higher proportion of female directors and the extent of voluntary disclosure. Thus, based on the above findings give some indications that the presence of women directors on the boardroom may positively influence the quality of disclosure on DRI and it is posited that:H4: The presence of women directors in the boardroom is positively associated to the quality of DRI disclosure.

2.6. Control Variables – Firm size

- Larger firms tend to disclose more information than smaller firms since their abilities in having adequate resources to bear for the information dissemination costs that most often at higher cost (Buzby, 1975) and the transparency of disclosure is perceived as a way to regain the investors’ confidence to improve the market capital’s efficiency (Singhvi & Desai, 1971). Prior studies have documented that size of the firm is a significant predictor of corporate disclosure activities. Consistent with the prediction, numerous studies find the association between firm size and the extent of voluntary disclosure is positively significant (e.g. Chow & Wong-Boren, 1987; Barako et.al., 2006; Haniffa & Cooke, 2005; Huafang & Jianguo, 2007; Eng & Mak, 2003; Ben-Amar & Boujenoui, 2006). In the Malaysian context, Wan Muhammad & Sulong (2010) empirically proven that larger companies increases the likelihood to disclose information voluntarily than its counterparts, small companies. Hence, based on the findings above, it is posited that: H5: The larger firms are positively associated to the quality of DRI disclosure

2.7. Control Variables – Auditor Size

- Several previous studies have supported the consideration of audit firm size as a determinant of the disclosure level (Firth, 1979; DeAngelo, 1981; Wallace et. al., 1994; Eng & Mak (2003). According to Ng et. al. (1992), bigger independent audit firms such as the Big-Four audit firms, are perceived more credible, since these audit firms are less likely to have a bonding relationship with one or few clients (Naser and Wallace, 1995). Therefore, the Big-Four audit firms will demand greater detail of disclosure from their clients (Ramli et.al , 2007). In addition, the larger audit firms have incentives to supply a higher level of audit quality, and they risk losing some of their reputation if they are associated with clients whose reporting practices are considered as ‘bad quality’ (De Angelo,1981). Findings in the prior studies (Forker, 1992; Eng and Mak; 2003; Chen and Jaggi, 2000) fail to document any statistically significant the relationship between auditor size and quality of disclosure voluntary disclosures. Hence, based on the arguments above, it is posited that:H6: The firms which are being audited by Big-Four auditing firm is positively associated to the quality of DRI disclosure.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection

- The researchers select Malaysian top 100 companies which have been ranked by the Minority Shareholders Watchdog Group (MSWG) in terms of firm’s market capitalisation, which were gathered from various sectors including financial sector since the corporate information disclosure’s requirement is applied throughout the various sectors and failed to do so will be not compromised by regulatory authorities (e.g. Bursa Malaysia & SC). The data information that pertaining to the directors-related information such as directors’ background, any related party transactions, etc. was gathered through corporate annual reports since the annual report is regarded as one of the most popular medium to convey the corporate information disclosure to the outsiders (Firth, 1984). Annual reports for the year 2011 was chosen for this study as the researchers only considered for the recent data, since some of the annual reports for the year 2012 were still not available during this study is conducted . In addition, since this study is undertaken for only one year, thus this is regarded as our limitation of study.

3.2. Research Instrument

- This paper is designed to use content analysis method through corporate annual reports in order to determine the directors-related information disclosure among the Malaysian top 100 companies which were ranked by the MSWG based on their market capitalisation. In this study, a scoring worksheet containing seventeen items is used and this scoring worksheet is adopted from Ramli (2001) study. It was considered appropriate to use the scoring worksheet in Ramli (2001) as the study was examining the CG disclosure in an international settings including Malaysia.

3.3. The Measurement of DRI Disclosure

3.3.1. Selection & Measurement of Disclosure Items

- The selected disclosure items as shown in Table 1 below provide the information that shareholders need for monitoring the directors’ behaviour such as information on their remuneration, boards composition, etc. since the all the corporate information that pertaining to the directors’ activitis or involvement are under public-scrutinised, hence these pressures require for transparent voluntary disclosure, and these disclosure items were adopted and adapted from the study by Ramli (2001).

3.4. Measurement of Explanatory Variables

|

4. Discussions of Findings

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

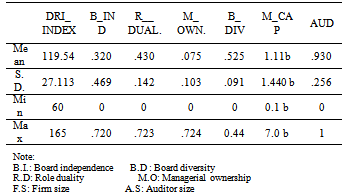

- Table 3 above summarises the descriptive results on the explanatory variables of the study. On average, the quality of the DRI disclosure index is fairly higher in which represents 91.2 per cent of total scores. Furthermore, the difference total scores among Malaysian top 100 companies were not so much deviated among themselves (s.d. = 27.113). This indicates that inherently Malaysian top larger companies have greater opportunities to strengthen their good image and reputation from the eyes of public by voluntarily discloses more information in the corporate annual reports. Besides, on average, the result has shown that majority of the top 100 companies are being audited by the Big-Four auditing firms. Since women directors nowadays are seeking for equal opportunities in the boardroom, thus the larger companies in Malaysia on average comprised at least 52.5% of women directors on the board. The minimum DRI disclosure index is scored by Pavilion Reit Bhd, while Genting Bhd has scored the maximum DRI disclosure index at total scores of 165 among other top 100 companies.

|

4.2. Inferential Statistics

4.2.1. Correlation Analysis

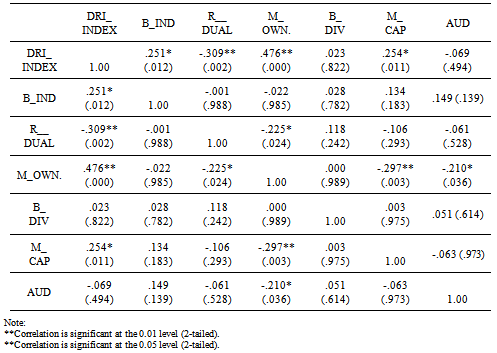

- Table 4 presents the correlation between the studied variables. Consistent with expectation, the higher proportion of independent directors (B_IND) is positively associated with the quality of DRI disclosure (DRI_INDEX), at 5 percent level (p = .012). This finding supports H1 that the increasing number of independent or outside directors (B_IND) stands together with the disclosure quality of DRI (DRI_INDEX) and it is consistent with the prior studies (i.e. Ho & Wong, 2001; Barako et.al., 2006; Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, 2010; Wan Muhammad & Sulong, 2010). This might indicate that the presence of independent directors (B_IND) on the board of the top larger firms is likely to carry out their duties as a monitoring function and at the same time to bring the objective judgment to the board’s decision. Consistent with H2, the association between the concurrent CEO-Chairman functions (R_DUAL) and the quality of disclosure on DRI (DRI_INDEX) is negative (p =.002, t = -.309). This gives an indication that the likelihood of the dominant personality (R_DUAL) to reduce the quality of DRI disclosure is low, thus their presence gives greater influence on the extent of voluntary disclosure. Surprisingly, contrary to H3, there is an increase of the quality of DRI disclosure (DRI_INDEX) when the board is made up of the higher proportion of shares held by managers/directors (M_OWN). Thus, this finding is found has no similarity with the previous studies (i.e. Ben-Amar & Bonjenoui, 2006; Samaha et.al., 2012; Eng & Mak, 2003). However, the presence of women directors is not significantly related with the quality of DRI disclosure (DRI_INDEX) and the association of the two variables does not support to H4. Of the control variables, the quality of disclosure (DRI_INDEX) are significantly and positively correlated with larger firms (p = .011) and this finding supports numerous empirical studies on the relationship between firm-specific characteristics and voluntary disclosure i.e. Chow & Wong-Boren (1987), Barako et.al. (2006), Haniffa & Cooke (2005), Huafang & Jianguo (2007), Eng & Mak (2003), and Ben-Amar & Boujenoui (2006). However, this study fails to document the positive link between the firms which being audited by larger (Big-Four) auditing firms and the greater disclosure (DRI_INDEX) (p= .495) and contrary to the prior studies by Firth (1979), DeAngelo (1981), Wallace et. al. (1994), Eng & Mak (2003), hence does not support to H6.

|

4.2.2. Regression Analysis

- Regression analysis was used to test the relationship between the explanatory variables and the dependent variable (DRI_INDEX). The empirical model is used to test the hypotheses as follows:Model 1DRI_Index = βo + β1B_IND it+ β2R_DUAL it + β3B_DIV it + β4M_OWN it + β5Ln_MCAP + β6AUD + εit Where,B_IND it = Board independenceR_DUAL it = Role dualityB_DIV it = Board diversityM_OWN it = Managerial ownershipLn_MCAP = Natural logarithm of firm’s market capitalisationAUD = Auditor size Εit = Error TermSince all the variables are not normally distributed, hence they have been transformed into normal scores, which is in line with Wallace and Naser (1995) that used rank scores. As shown in Table 7, the value of R square for the quality of DRI disclosure (DRI index).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

5. Conclusions

- This study aims to investigate whether corporate governance (CG) mechanisms could give impacts towards enhancing the quality of DRI disclosure among Malaysian top 100 MCG, after controlling their firm-specific characteristics. The corporate governance (CG) practices are expected to be enhanced with the improvement of CG requirements by the regulatory authorities as a way to increase the efficiency in capital market and its allocation of resources and also to regain investors’ confidence when the separation of ownership and control is separated. To mitigate the agency conflicts in the principal-agent relationship, firms are ingenious to reduce the public pressures through providing better transparent disclosure. The issues of providing voluntary disclosures in the corporate reports have become hot debated and been widely discussed in the literature since last decade, when the corporate scandals are rooted from the weak corporate governance systems. Numerous studies have been undertaken to investigate on the association between the corporate governance attributes and the extent of voluntary disclosure (i.e. Eng & Mak, 2003; Ho & Wong, 2001; Huafang & Jianguo, 2t006; Chen & Jaggi, 2001; Haniffa & Cooke, 2002, 2005; Akhtaruddin, Hossain, Hossain & Yao, 2009; Karagul and Yonet, 2011; Bhasin, 2012; Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, 210; Bhasin, 2012; Samaha, Dahawy, Hussainey & Stapleton, 2012; Wan Mohamad & Sulong, 2010). Given the increasing importance of voluntary disclosure, thus the researchers attempt to examine the quality of directors-related information disclosure since the information that pertaining to the directors is of interests of the shareholders to ensure that the directors are efficiently carrying out their duties in monitoring actions and protect the investors’ rights. In order to meet the objective of the study, the researchers have adopted and adapted the measurement of the disclosure quality done by Ramli (2001). The total scores of firms’ disclosure index have been derived from using the modified unweighted dichotomous index. On average, the descriptive results reveal that among top 100 MCG (ranked by the Malaysian MSWG 2011), they have achieved at moderately higher in terms of their DRI information level. Consistent with the expectations, correlation analysis reports that the presence of independent (outside) directors is significantly positively related to the quality of DRI disclosure among the top 100 MCG. Larger firms inherently tend to voluntarily disclose information to their shareholders that are perceived as a way to maintain its good recognition and reputation in practising corporate governance best practices from the public perspective. In addition, prior studies have well-documented that the voluntary disclosure decreases when the directors hold dual position simultaneously. It is interesting to know that the association between the quality of DRI disclosure and managerial ownership is positive, in the notion that the directors are more likely to enhance the extent of disclosure when they hold higher proportion of shares in the company. Nonetheless, the presence of female directors on the board and the companies which being audited by larger (Big-Four) auditing firms, fail to find the significant relationship between the variables. The Big-Four auditing firms play a major role in attaining that the larger firms are complied with mandatory information disclosure, but to increase the initiatives for providing better voluntary disclosure is not on their hands. Besides, since this study has undertaken for single period of 2011, it is recommended that the similar study could be expanded by collecting data that involving number of years (longitudinal study), and also by adding more corporate governance variables perhaps it may provide useful insights and fruitful contribution to the literature.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to acknowledge and to express our deep gratitudes and heartiest appreciation to our family, participating employers and students, encouraging friends who willing to provide us with the fruitful ideas and their kind cooperation to make this successful research.

References

| [1] | Akhataruddin,M.,Hossain,M.A.,Hossain,M.,Yao Lee.,” Corporate Governance And Voluntary Disclosure In Corpoarte Annuals Reports Of Malaysian Listed Firms”,JAMAR,Vol.7,No.1,pp.1-19,2009. |

| [2] | Al-Shammari,B., Al-Sultan,W.,” Corporate Governance and Voluntary Disclosure in Kuwait”, International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, Vol.7,pp.262-280, 2010 |

| [3] | Anderson,M.,Daoud,M., “Corporate Governance Disclosure” Undated. |

| [4] | Baek,H.Y, Johnson,D.R.,Kim,J.W.,” ManagerialOwnership,Corporate Governance and Voluntary Disclosure, Journal of Business and Economic Studies,Vol.15,No.2,pp.44-61, 2009. |

| [5] | Barako, D.G, Hancock, P,Izan,H.Y.”Relationship Between Corporate Governance Attributes and Voluntary Disclosures in Annual Reports: The Kenyan Experience”, Financial Reporting, Regulation and Governance, pp.107-125, 2006. |

| [6] | Bhasin,M.,”Voluntary’ Corporate Governance Disclosure Made in the Annual Report: An Empirical Study”, International Journal of Management and Innovation, Vol.4, Issue 1, pp.46-67, 2012. |

| [7] | Bujaki,M.,McConomy,B.”Corporate Governance:Factors influencing Voluntary Disclosure by Publicly Traded Canadian Firms”,Canadian AccountingPerspective,pp.105,2002. |

| [8] | Buzby,L.S.,”Company Size, Listed Versus Unlisted Stocks and the extent of Financial Disclosure”, Journal of Accounting Research,pp.16-37,1974. |

| [9] | Byards,D., Lee,Y.,Weintrop,J.,”Corporate Governance and the quality of financial analysts’ information”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol.25, pp.609-625, 2006. |

| [10] | Cerf, A.R., “ Corporate Reporting and Investment Decisions”, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1961. |

| [11] | Chen,C.J.P., Jaggi B.,”Association between independent non-executive directors,family control and financial disclosures in Hong Kong”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, pp.285-310,2000. |

| [12] | Eng,L.L., Mak,Y,T,,”Corporate Governance and voluntary Disclosure”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, pp.325-345,2003. |

| [13] | Firth, M., “The Extent of Voluntary Disclosure in CorporateAnnual Reports and its Association with Security Risk Measures”, Journal of Applied Economics, 16, pp. 269-277, 1984. |

| [14] | Gul, F.A. & Leung, S., “ Board Leadership, Outsider Directors’ Expertise and Voluntary Corporate Disclosure”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 23, 351–379, 2004. |

| [15] | Haniffa,R.M.,Cooke,T.E.,”Culture,Corporate Governance and Disclosure in MalaysianCorporations”ABACUS,Vol.38,No.3,2002. |

| [16] | Haniffa,R.M.,Cooke,T.E.,”The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol.24,pp391-430,2005. |

| [17] | Healy,P.M.,Palepu,K.G.,”Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure and the capital markets:A review of the empirical disclosure literature” Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol.31,pp 405-440,2001. |

| [18] | Ho,S.S.M.,Wong,K.S.,”A study of the relationship between corporate governance structuresand the extent of voluntary disclosure” Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, Vol.10,pp. 139-156,2001. |

| [19] | Huafang,H.,Jianguo,Y.,”Ownership structure,boardcomposition and corporate voluntary disclosure” Journal of |

| [20] | Jensen, M.C. & Meckling, W.H.,” Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behaviour, Agnecy Costs and Ownership Structure”, Journal of Financial Economics, 3, pp.305-360, 1976. |

| [21] | Karagul, A.A, and Yonet, N.K., “Impact of Board Characteristics and Ownership Structure on Voluntary Disclosure: Evidencefrom Turkey”, Retrieved from www.scholar.google.com on 1 October 2012, pp.1-22, 2011. |

| [22] | Kelton, A.S. & Yang, Y., “The Impact of Corporate Governance on Internet Financial Reporting”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 2008. |

| [23] | Lang, M. and Lundholm, R., “Cross-sectional determinants of analyst ratings of corporate disclosures”, Journal of Accounting Research (JSTOR), Vol. 31, No.2 246-271, 2001. |

| [24] | Mohamad,W.W.I.,Sulong,Z.,”Corporate GovernanceMechanisme and Extent of Disclosure : Evidence from Listed Companies in Malaysia.” International Business Research, Vol.3, No.4, pp.216-228, 2010. |

| [25] | Nelson,T.,Park,Y.W.,Huson,R.M.,”Executive Pay and Disclosure Environment:Canadian Evidence” Journal of Financial Research, Vol.XXIV,No.3,pp.347-365,2001. |

| [26] | Patel,S.A.,Balic,A.,Bwakira,L.,”Measuring transparency and disclosure at firm-level in emerging markets.” Emerging Market Review, Vol.3, pp. 325-337, 2002. |

| [27] | Ramli, M.I., “Disclosure in Annual Reports: An Agency Perspective in An International Setting, Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Plymouth, UK, 2001. |

| [28] | Samaha,K.,Dahawy,K.,Hussainey,K.,Stapleton,P.,” The extent of corporate governance disclosure and its determinants in a developing market: The case of Egypt.” Advance in Accounting, Incorporating Advances in International Accounting, pp. 1 -11, 2012. |

| [29] | Sun,N.,Salama,A Hussainey,K,Habbash,M.”CorporateEnvironmental disclosure, corporate governance and earnings management”, Managerial AuditingJournal,Vol.25,No.7,pp.679-700,2010. |

| [30] | Wan Muhammad, W.R. & Sulong, CG Mechanisms and the Extent of Disclosure: Evidence from Listed Companies in Malaysia, International Business Research, Vol. 3, No.4, p.216-228, 2010. |

| [31] | Zulkafli,A.H.,Samad,A.M.Fazilah,Ismail,M.I.,”Corporate Governance in Malaysia” Undated. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML